The Beginnings: Opera in Florence and Mantua

Peri, Cavalieri, and Caccini

Early in 1598, Dafne—Ottavio Rinuccini’s libretto set to music by Jacopo Peri, with some parts by Jacopo Corsi—was played before a small audience in Corsi’s palace, and it was repeated, with changes and additions, for several years thereafter during Carnival.1 In the preface to both the libretto and score of Euridice, Rinuccini and Peri explained that Dafne was an experimental work, designed to put into practice their humanistic ideas about the power of music.2 For this reason, Dafne was to be entirely sung, in imitation of what they believed to be the Greek and Roman manner of performing tragedies. In view of the great historical interest of this score, the first dramatic pastorale fully set to music, it is singularly unfortunate that, with the exception of a few short excerpts, none of the music has survived. Those excerpts, however, are important, for they reveal three different styles of composition: a simple, recitation style adapted to the stanzaic pattern of the strophic text in the prologue; a structured melodic style in the aria “Chi da’ lacci d’amor”; and most significantly, a freely conceived declamatory style to convey the messenger’s description of Dafne’s transformation into a laurel.

The earliest operas for which complete scores survive are by Emilio de’ Cavalieri, Jacopo Peri, and Giulio Caccini.3 Cavalieri’s La rappresentazione di Anima e di Corpo was staged in the Oratorio di S. Maria in Vallicella at Rome in February 1600 and is, in effect, a sacred opera.4 It consists of a prologue that is spoken and three acts entirely set to music. The text, with its moralizing purpose and allegorical figures (Soul, Body, Pleasure, Intellect, and others), shows its connection with the sacred dramas and morality plays of the sixteenth century.5 Peri, in the preface to his Euridice, considered Cavalieri to be the first to apply the principle of monody to a work designed for the stage. Cavalieri made a similar claim for himself, but this was subsequently debated by those associated with the Florentine camerate and academies. There was no debate, however, over the fact that the printing of Cavalieri’s sacred opera in September 1600 predated the publication of the operas created by Peri and Caccini.

Two complete settings of Rinuccini’s poem Euridice exist—one by Peri and one by Caccini. Peri’s setting was offered as a private entertainment in October 1600 at the Pitti Palace in Florence in conjunction with the festivities planned by Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici to celebrate the marriage of Maria de’ Medici to Henry IV of France and Navarre. It was published four months later.6 Caccini’s setting was published at about the same time but not performed in its entirety until 1602.7 Peri’s Euridice was produced on a very small scale and most likely would not have been performed at all had not Jacopo Corsi offered to defray the costs of the staging. This opera production should have been a newsworthy event, given its experimentation with a new dramatic style of composition, but its importance was initially overshadowed by a performance three days later of Gabriello Chiabrera’s Il rapimento di Cefalo, a court-sponsored spectacle for which Caccini composed most of, if not all, the music.8

The Euridice poem is a pastorale on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice—a favorite subject for operas, owing not only to the fact that the mythical hero is himself a singer but also to the combination of a simple action with a variety of emotional situations (love, death, suspense, rescue from danger) and possibilities for striking scenic effects. In the classic version of the myth, the condition of the rescue of Eurydice from Hades is that Orpheus shall not look back or speak to his wife until they arrive at the upper world, but in his anxiety he looks back, and Eurydice is returned to death irredeemably. Poets have invented all sorts of expedients to avoid this tragic outcome.9 Rinuccini’s solution is simplicity itself: no condition at all is attached to the rescue, and Eurydice is happily restored to life. The divisions of Rinuccini’s poem are as follows:

Prologue. “Tragedy,” in a solo of seven strophes, announces the subject and makes flattering allusions to the noble auditors. (This prologue became the prototype for paying homage to royal patrons.)

Rejoicings. Shepherds and nymphs celebrate the wedding day of Orpheus and Eurydice. Choruses; entrance of Eurydice; at her invitation, all join in a dance (“Al canto, al ballo”). Entrance of Orpheus (solo, “Antri, ch’a miei lamenti”) with his friends Arcetro and Tirsi.

Death of Eurydice. As usual in pastoral poetry, this is not enacted on the stage but narrated by a messenger (represented in Peri’s version of 1600 by a boy soprano).

Lamentations. A long scene, beginning with a solo by Orpheus and climaxing in a choral threnody with a recurring phrase (“Sospirate, aure celeste”).

Epiphany. Arcetro as messenger relates how Orpheus in his grief wished to kill himself, but the goddess Venus came down from heaven to console him and encourage him to demand Eurydice from Pluto in Hades.

Descent into Hell (change of scene). After a brief dialogue between Orpheus and Venus, there follows a solo by Orpheus (“Funeste piagge”). Then, supported by some of the deities of Hades, he argues and pleads with Pluto until the latter yields. The scene closes with a solemn antiphonal chorus of the infernal spirits.

Resurrection (return to the opening scene). A messenger (Aminta) announces the happy return of Orpheus and Eurydice. Solo by Orpheus (“Gioite al canto mio”); closing choruses and dances.

The two versions of Peri and Caccini are similar. Peri’s is somewhat more forceful in tragic expression, whereas Caccini’s is more tuneful, excels in elegiac moods, and gives more occasion for virtuoso singing. Neither score has an overture, and there is almost no independent instrumental music. At the first performance of Peri’s work, as we learn from his foreword, there were at least four accompanying instruments, placed behind the scenes: a gravicembalo (harpsichord), chitarrone (theorbo), lira grande (large lyre, a bowed chord–instrument with as many as twenty-four strings), and liuto grosso (literally “large lute”).10 Doubtless these continuo instruments alternated or were used in various combinations, making possible a considerable variety of tonal color. What notes did they play? The score gives only the bass, with a few figures below the melody of the solo part; the exact realization of the bass is a matter about which editors have differed, and it is essential to keep this in mind when dealing with modern editions of early operas.11 In the case of Peri and Caccini, the probability is that the harmonies were simple, with few nonharmonic tones or chromatics. Certainly the basses do not suggest many contrapuntal possibilities in the texture of the inner parts. The bass has no importance as a line, as may be recognized not only by its stationary, harmonic character but also by the absence of any sustaining bass instrument in the orchestra.

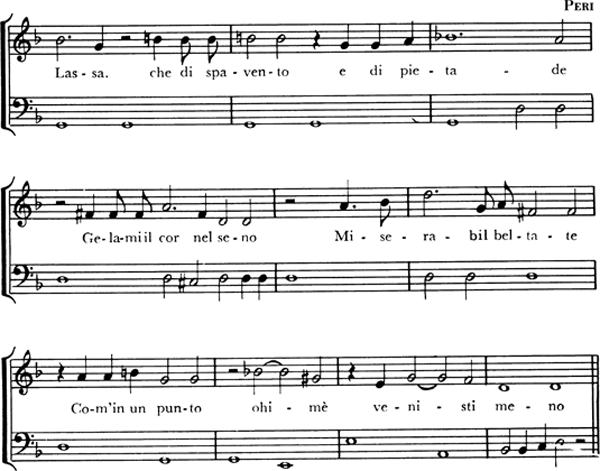

The action in both Euridice operas is carried on by solo voices in the new Florentine monodic style, consisting of a melodic line not so formal as an aria or even an arioso, yet not at all like the recitative of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Italian opera, which is characterized by many repeated notes and an extremely rapid delivery.12 The operatic monody of Peri and Caccini is different from all these. Its basis is an absolutely faithful adherence to the natural rhythms, accents, and inflections of the text, following it in these respects even to the extent of placing a full cadence regularly at the end of every verse.13 Occasionally a solo will be given musical form by using the same bass for two or more strophes; long scenes are commonly unified by means of choral ritornellos. But the prevailing impression in the solo portions is one of almost rhapsodic freedom, as though the melodic line existed solely to add the ultimate fulfillment of song to a poetic language already itself more than half music. Rarely—too rarely—the song will rise to picturesque and pathetic expression, as at the end of the messenger’s narration of the death of Eurydice in Caccini’s setting (example 4.1) or the heartbroken exclamation of Dafne in Peri’s verison (example 4.2).

In contrast to the free-rhythmed portions are a few songs in regular meter, either solos or solos alternating with chorus. These songs are in the nature of lyrical interludes in the action; they are placed usually at the ends of scenes, where the effect of dropping into a metrical pattern is similar to the effect produced by a pair of rhymed verses at the end of a scene in Shakespeare, contrasting with the preceding blank verse. One such air is the well-known “Gioite al canto mio” of Peri’s setting, sung by Orpheus in the closing scene.

The “chorus,” consisting of probably not more than ten or twelve persons, is on stage during nearly all the action and plays an important part both dramatically and musically. From time to time it engages in the dialogue, but its principal functions are to lend unity to a scene (as already mentioned) by means of short phrases in refrain and to provide sonorous and animated climaxes, with combined singing and dancing. Such a climax occurs, for example, with the choral ballet “Al canto, al ballo,” after the first entrance of Eurydice (example 4.3).

The defects of Peri’s and Caccini’s operas, which came to be recognized as soon as the novelty of the new style of composition (recitar cantando) had worn off, were the weakness of characterization, the limited range of emotions expressed, the lack of clear, consistent musical organization, and above all the monotony of the solo style. Especially for this last reason, Giovanni Battista Doni, the foremost opera theorist of the early seventeenth century, not only advocated the plentiful use of arias and choruses to relieve the “tedium” of the recitative, but as late as 1635 argued that the ideal dramatic work was one in which music alternated with spoken dialogue.14

EXAMPLE 4.1 Euridice

EXAMPLE 4.2 Euridice

EXAMPLE 4.3 Euridice

Monteverdi

Some of the early masterpieces of the opera repertoire were composed by Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643).15 At his hands, the genre acquired a wealth of musical resources and a power and depth of expression that make his music dramas still living works after almost four hundred years. Of his nineteen dramatic or semi-dramatic compositions, only six, including three operas, have been preserved in their entirety.16

Monteverdi was born at Cremona and received his musical education from Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, director of music at the cathedral in that city. Beginning in 1590 he entered the employ of Grand Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua as a performing musician, playing either the violin or the viola da gamba, and from 1602 until 1612 served as maestro di cappella of the ducal chapel. His first opera, Orfeo, was commissioned to entertain the aristocracy during Carnival.17 It was set to a text by the duke’s secretary, Alessandro Striggio, the younger, and staged on February 24, 1607 before members of the Accademia degli Invaghiti.18 Vincenzo Gonzaga was so impressed with the production he arranged for a second performance to be given a week later “in the presence of all the ladies of the city.”19

Both the text and music of Orfeo invite comparison with Euridice by Rinuccini and Peri, for the two operas hold much in common, including a structural division into five sections, the pastoral setting, and the use of the chorus. Where the two differ significantly is in the manner in which Rinuccini and Striggio conclude their respective librettos. Rinuccini altered the original myth in order to provide a lieto fine in keeping with the festivities for the Medici wedding, whereas Striggio, in the version printed for the first performance, followed the ancient form of the myth, according to which Orpheus met his death by being torn to pieces by a band of women in a Dionysiac frenzy.

Curiously, Monteverdi’s score of Orfeo, as printed in 1609 and again in 1615, differs from the two printings of Striggio’s libretto in 1607. The ending of the opera has been changed and the choruses found at the close of the second and fourth acts of the original libretto have been shortened:

Prologue. Five strophes, sung by “Music”—a significant contrast to Rinuccini’s prologue, sung by “Tragedy.”

Rejoicings (Act I and first half of Act II). Broadly arched poetic and musical structures, combining solo arias, recitatives, duets, choruses, and orchestral ritornellos.

Death of Eurydice (this and the next section comprise the second half of Act II). Introductory recitatives; narration by the messenger (Silvia)

Lamentations. Solo of Orpheus (“Tu se’ morta”); orchestral interlude; finale, duets with choral refrain (“Ahi, caso acerbo”).

Epiphany (this and the next section comprise Act III). “Hope” consoles and encourages Orpheus.

Descent into Hell. Aria of Orpheus (“Possente spirto”); recitatives, orchestral interludes, closing chorus.

Resurrection (first half of Act IV). Orpheus and the infernal deities (recitatives).

Second Death of Eurydice (second half of Act IV). Scena: recitatives by Orpheus, with short phrases by others; solemn reflective closing chorus.

Second Lamentation (first part of Act V). Solo scena, Orpheus (with an “echo” song).

Ascent into Heaven (last part of Act V). Apollo takes Orpheus with him to dwell forever in heaven. Duet (“Saliam cantando”), short closing chorus, and ballet (moresca).20

There is considerable debate among scholars concerning the differences that exist between libretto and score.21 One theory suggests that the cloud machine required in the final scene for Apollo and Orpheus to ascend to heaven probably could not have been accommodated in the small room where the initial performance is believed to have been held and therefore some have argued that the Bacchic scene printed in the libretto was substituted for the lieto fine that concluded the original versions of both libretto and score. Another theory that holds some credence is that Monteverdi did not revise the ending of his score until the spring of 1607, when a third performance of Orfeo was planned by Vincenzo Gonzaga. The occasion for this entertainment was to have been a visit by Carlo Emanuele, Duke of Savoy, to discuss plans for the marriage of his daughter to Francesco Gonzaga, and understandably the court would have welcomed a lieto fine for such an event. Carlo Emanuele, however, changed his plans and that performance never took place.22 Despite two publications of the score, Orfeo failed to attract interest beyond the Mantuan court, for no other early seventeenth-century performances of this opera have come to light.23

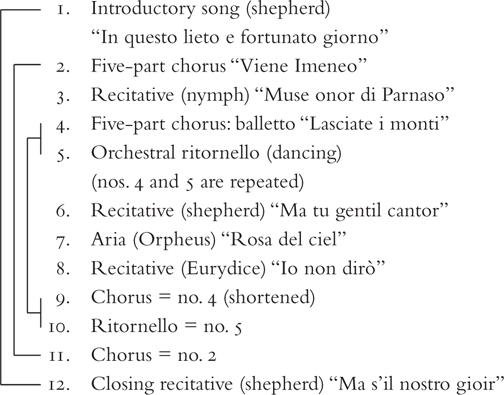

TABLE 4.1 Orfeo: The design of Act I

Monteverdi’s “favola in musica” is a work of extraordinary and impressive symmetry. All the essential dramatic action takes place in Acts II through IV. Act I is a prelude; Act V an epilogue. The musical and dramatic center of the whole is Orpheus’s aria “Possente spirto” in Act III, where he opens his way into the underworld by the charm of music. Equal care for the grand lines of symmetry is evident in each separate act and subdivision. The first part of Act I, for example, is shaped as shown in table 4.1.

The music of Orfeo was greeted by contemporaries as a new example of the Florentine style, and indeed the general plan of the opera—a pastorale, with monodic declamation—justified this view. Nevertheless, the differences are fundamental. Monteverdi was a musician of genius, soundly trained in technique, concerned very much with musical and dramatic truth and very little with antiquarian theories. He combined the madrigal style of the late sixteenth century with the orchestral and scenic apparatus of the old intermedi and a new conception of the possibilities of monodic singing. Orfeo represents the first attempt to apply the full resources of the art of music to drama, unhampered by artificial limitations.

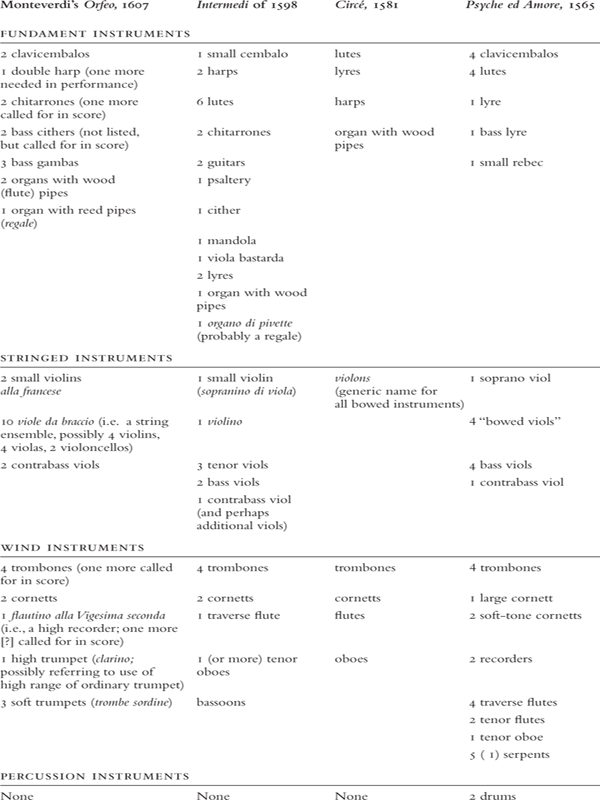

The imposing list of orchestral instruments at the front of the score gives an idea of the extent and importance of the instrumental music of Orfeo.24 The similarity of this orchestra to those of the earlier intermedi may be seen by a glance at table 4.2. The great number and variety of “fundament” (chord-playing) instruments is characteristic of the sixteenth century. Of course, not all the instruments were used at once, and undoubtedly many of the players doubled, so that there were not as many performers as there were different instruments. The players united for certain numbers (such as the opening toccata, some of the sinfonias, and accompaniments of some of the choruses), but at many places Monteverdi indicated in the score precisely what instruments were to be used, his choice obviously being dictated not only by the desire to secure variety of color but also as a means to characterize the dramatic situation. A detailed study of the score in this respect is extremely interesting. For example, in Act III, the voice of Charon, the ferryman of the Styx, is accompanied by the regale (an organ with reed pipes); Orpheus’s aria “Possente spirto” has with each strophe a different set of instruments; Charon’s slumber is depicted by the strings with an organ of wooden pipes, playing “very softly”; the same organ alone accompanies Orpheus’s song as he crosses the Styx; and the final chorus of infernal spirits (two altos, a tenor, two basses) is accompanied by a combination of reed and wood organs, five trombones, two bass gambas, and contrabass viol—this in accordance with the traditional usage in the sixteenth-century intermedi for such scenes.25

The overture to Orfeo, called “toccata,” is probably a dressed-up version of the customary opening fanfare. It consists of a brilliant flourish on the chord of C major, played three times by the full orchestra. In addition, the score contains ten short instrumental pieces called “ritornello” and five called “sinfonia”; some of these pieces recur one or more times. In early seventeenth-century opera the distinction between “ritornello” and “sinfonia” is not always clear, nor are the designations consistent.26 In principle a ritornello is, as the name suggests, a recurring interlude in connection with a song. Thus the prologue to Orfeo opens with a ritornello (example 4.4) that is repeated four times in a shortened form after each stanza and once in its original form at the end of the prologue. Moreover, Monteverdi brings in the same ritornello at the end of Act II, the turning point of the drama, and again at the end of Act IV, the close of the significant dramatic action—thus making it a kind of leitmotif symbolizing the “power of music,” the central idea of the opera as announced in the prologue:

Io la musica son, ch’ai dolci accenti

so far tranquillo ogni turbato core.

TABLE 4.2 Monteverdi’s Orchestra and Its Predecessors

EXAMPLE 4.4 Orfeo, Ritornello from the prologue

A sinfonia is generally a more or less independent instrumental piece used for an introduction or postlude or for depicting events on the stage. The sinfonias in Orfeo are serious, solidly chordal pieces, with occasional short points of imitation, full texture, and much crossing of parts. The ritornellos are more highly scored, sequential in structure, and more contrapuntal in texture.

The aria “Possente spirto” in Act III is a remarkable example of the florid solo style of the period. It has six strophes, of which all but the fifth are melodic variations over an essentially identical bass. For each of the first four strophes, Monteverdi wrote out a different set of vocal embellishments, which he incorporated in the score on an additional staff. These embellishments are doubtless similar to those an accomplished singer of the time would have been expected to add to a plain melodic line. The practice of having solo instruments “concertize”—that is, collaborate and compete—with the voice, as Monteverdi does here, was destined to become important in later seventeenth- and eighteenth-century opera arias. The employment of such elaborate vocal and instrumental effects at this place is not merely for purposes of display but is calculated to suggest Orpheus’s supreme effort to overcome the powers of Hades by all the strength of his divine art. At the same time, the wild, fantastic figures of the music seem to depict the supernatural character of the scene. “Possente spirto” is also remarkable in that it serves as a forerunner to the prayer and incantation types of arias found in later operas.27

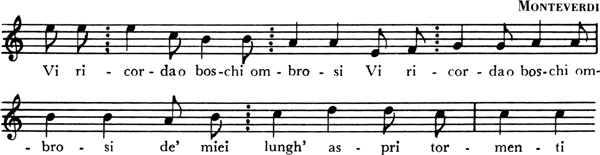

Quite different kinds of songs are found in the first part of Act II. The act begins with a little air by Orpheus in periodic phrasing and three-part form—a miniature da capo aria. The whole scene is a lyric interlude, containing no dramatic action, and appropriate to the joyous pastoral atmosphere are the duet of the shepherds (“In questo prato adorno”), with its ritornello for two high recorders played behind the scenes, and Orpheus’s strophic solo “Vi ricorda, o boschi ombrosi,” with its effect of alternating 6/8 and 3/4 meters (example 4.5).

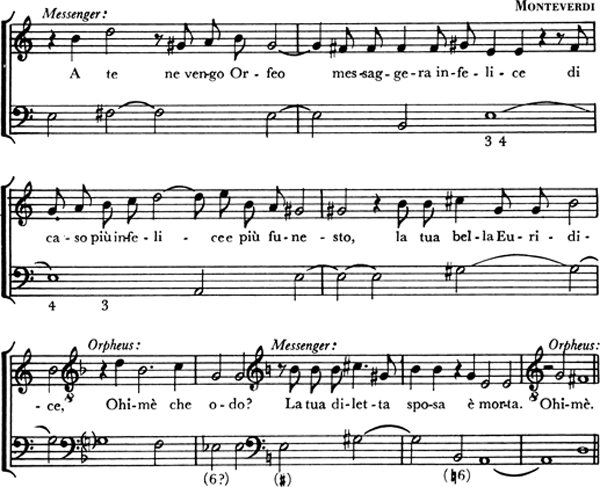

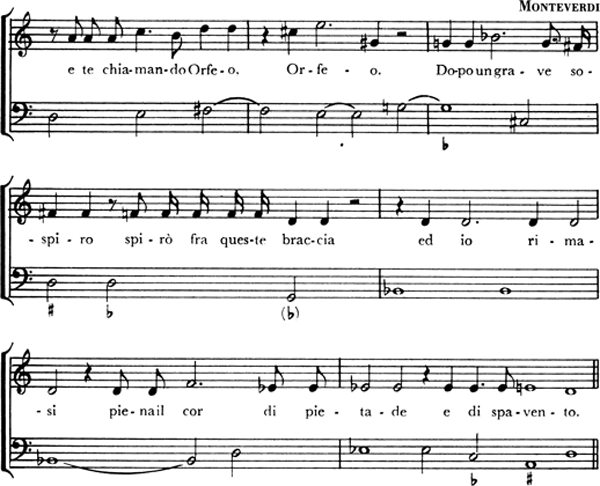

Songs of this sort, which show the traits of popular style, establish the background for the abrupt contrast at the entrance of the messenger with the news of Eurydice’s death. Nowhere is Monteverdi’s superiority over the early Florentine composers more manifest than in the startling change of mood he achieves at this point and in the dialogue immediately following, with the alternating E-major and G-minor harmonies at Orpheus’s exclamations (example 4.6). The harmonic contrast here was undoubtedly underlined by contrast of tone color in the instruments used for the realization of the basso continuo. The ending of the messenger’s account (example 4.7) may be compared with the corresponding passage in Caccini’s Euridice (see example 4.1), as showing Monteverdi’s grasp of the dramatic possibilities of the monodic style. The choruses of Orfeo are more numerous and more important than those in the early Florentine operas. Some are intended to accompany dancing, such as the chorus “Lasciate i monti” in Act I; others are in madrigal style, such as the ritornello chorus “Ahi, caso acerbo” at the end of Act II. The choruses of spirits at the end of the third and fourth acts exploit the somber color of the lower voices in a thick texture, supported by the trombones.

EXAMPLE 4.5 Orfeo, Act II

EXAMPLE 4.6 Orfeo, Act II

EXAMPLE 4.7 Orfeo, Act II

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of Orfeo is Monteverdi’s sense of form, of a logically articulated, planned musical structure that unfolded before the audience without breaks between the scenes. This is apparent not only in the use of such devices as strophic songs and instrumental ritornellos and in the broad symmetrical structure of the large units but also in the monodic portions, such as the entire recitative of the messenger in Act II, from which example 4.7 is quoted. Such places in Peri and Caccini were nearly formless vocal rhapsodies; here, they are organized into musical units in which the freedom of declamation is admirably balanced by the careful plan of the passage as a whole.

Monteverdi’s second opera, Arianna, was on the same large scale as Orfeo, insofar as can be judged from the libretto. The first performance of Arianna took place at Mantua in May 1608 as part of the festivities celebrating the marriage of Francesco Gonzaga and Margherita of Savoy. The opera was staged in the ducal palace where a temporary theater capable of accommodating several thousand guests had been constructed. Also in connection with these festivities, Guarini’s L’Indropica was performed with spectacular intermedi, as was Monteverdi’s dramatic ballet Il ballo delle ingrate.

Arianna was never published nor does the full score survive in manuscript. The only music that has been preserved is the famous “lament,” which the heroine sings when she discovers Theseus has abandoned her on the island of Naxos. This song was probably the most celebrated monodic composition of the early seventeenth century and was declared by Gagliano to be a living modern example of the power of ancient (that is, Greek) music, since it was said to have moved the audience to tears.28 The Mantuan court chronicler Federico Follino also had similar words of praise for the initial production.

There is but one source that offers the entire text of the lament and that is Rinuccini’s libretto, printed in 1608. Several versions of Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna survive, including, among others, one that is limited to the nine sections allotted to the soloist and another that sets only the first five sections for solo voice and basso continuo. It is this latter version, first published in 1623, that is the best known.29 Monteverdi also arranged this lament as a five-part madrigal in 1610 (and later printed in 1614, in his sixth book of madrigals), and he used the music yet again for a sacred contrafactum (1640) entitled Pianto della Madonna.

Of the dozen or so operas after Arianna, only the last two, Il ritorno d’Ulisse and L’incoronazione di Poppea, have been preserved. These will be considered later (chapter six) in connection with opera in the public theaters of Venice, the city where Monteverdi spent the remaining years of his life following his resignation from the Mantuan court in 1612.30 It was also in Venice that Arianna had a revival in 1640 to inaugurate the Teatro San Moisè.

Gagliano

Another notable early opera is the Dafne of Marco da Gagliano (1582–1643), a native of Florence and founding member of the Florentine Accademia degli Elevati, established in 1607 under the protection of Ferdinando Gonzaga.31 Almost all Gagliano’s works were written for the Florentine court.32 Notable exceptions include Dafne, which was commissioned by Vincenzo Gonzaga for performance at the Mantuan court during Carnival in 1608. The score was published later that same year.

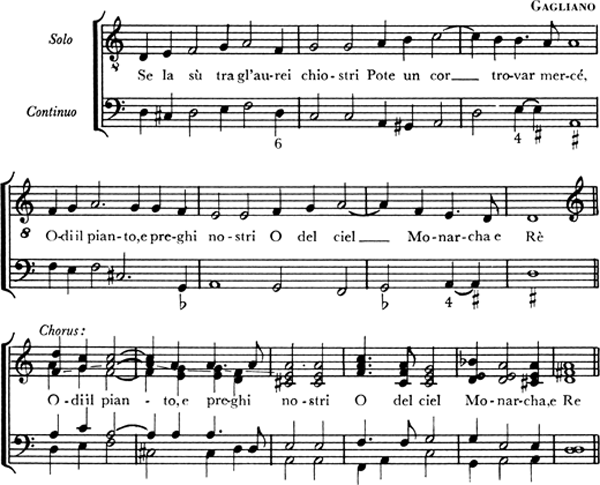

The libretto of this work is adapted from Rinuccini’s poem of 1594, which in turn had been taken, in part, from one of the intermedi of 1589. The action is divided into two parts:Apollo slays the Python with his arrows but is himself wounded by the arrows of Love; he vainly pursues the nymph Daphne, who is changed into a laurel tree just as he is about to seize her. The latter episode does not take place on the stage, but is narrated by a messenger. The prologue is sung by Ovid, from whose Metamorphoses the story is taken. The music is essentially like that of the Florentine monodists, to whose doctrines Gagliano professed adherence, but is more animated in the melodic line and supported by more logical basses and richer harmonies. The free monody occasionally alternates with aria-like sections, and it is possible to see in certain places the outline of the future “recitative and aria” grouping. An “echo song” (“Ebra di sangue”) exemplifies a musical and poetic conceit that long remained popular in opera. Some of the arias have instrumental ritornellos, and there is an instrumental dance (ballo) at the end, as in Peri’s Euridice. There is no overture, but Gagliano in his preface to the score mentions that a sinfonia of the various instruments, which accompany the choruses and play the ritornellos, should be played before the prologue—a direction that suggests that similar introductory pieces may have been performed with the earlier operas of Peri and Caccini. The chorus is very prominent in Gagliano’s work; it is sometimes associated with the action and at other times it appears in purely contemplative passages. Solos, duets, and short instrumental interludes lend variety to the choral numbers. An air with choral refrain is illustrated in example 4.8. The whole score, in sum, shows abundant musical resources, drawing on the tradition of the old intermedi as well as the new monodic recitative.

In the preface to Dafne Gagliano offers an extensive discourse on the opera’s initial production that took place not in a theater with a proscenium stage but in a ducal salon where the stage and scenery had to be erected specifically for this event.33 Among the various elements he stressed as being important for a successful performance was that of having the gestures and movements of the protagonists coordinated with the music as a means for making the sung text comprehensible.34

EXAMPLE 4.8 Dafne

As important as the operas discussed in this chapter are for the history of opera, they did little to change the attitudes of their patrons as to the type of entertainment preferred for festive events. During the opening decades of the seventeenth century, the Florentine and Mantuan courts delighted in the extravagant spectacles offered by plays with elaborate intermedi, court ballets, and tournaments. Relatively little interest was expressed for the new musico-dramatic form of entertainment and hence, opera productions recorded before 1620 are sporadic and few in number. It would take the enthusiastic support from patrons such as the Barberini in Rome and the paying public in Venice to bring opera into the mainstream of European culture.

1. In the preface to his opera Euridice (1600), Peri informs the reader that some of the music in his Dafne was composed by Corsi. Marco da Gagliano, in the preface to his Dafne (1608), gives similar information about Corsi’s involvement. Two excerpts by Corsi are extant. See Porter, “Peri and Corsi’s Dafne”; Hanning, “Glorious Apollo”; Carter, Music in the Late Renaissance & Early Baroque Italy.

Performances of Dafne are known to have occurred in 1598 (1597 by the Florentine calendar), 1599, and 1600. A libretto (no date or publisher; now in the New York Public Library) may have been printed for the 1598 performance. If so, this would be the earliest known printed libretto. Cf. Sternfeld, “The First Printed Libretto,” and Carter,” Letter to the Editor” for two different opinions about this libretto.

2. These same ideas were expressed in the prologue to the opera. So effective was this prologue, sung by a single protagonist (Tragedy), it became the prototype for Rinuccini’s prologues to his later librettos.

3. There is considerable disagreement over what scores qualify as the first “operas.” For example, Pirrotta, with Povoledo, Music and Theatre, 237, dismisses any proposal to place Peri’s Dafne in this category because he finds the surviving fragments to be “immature and preliminary.” Cavalieri’s Rappresentazione is considered by some scholars to be an oratorio because of its spiritual and allegorical subject matter, and it is, therefore, also excluded from this category. For a different opinion about why these two works should be listed among the earliest operas, see Sternfeld, The Birth of Opera, 29–32.

4. In the preface to his Rappresentazione, Cavalieri provides instructions for performing sacred dramatic music and pastorales. Presumably his comments were meant to apply to his own pastorales—Il satiro (1595), La disperazione di Fileno (1598), and Il giuoco della cieca (1599)—the texts and music of which are no longer extant. Facsimile and transcription editions of Rappresentazione were published in 1967 and 1979, respectively. For more about opera in Rome, see chapter five.

5. The text was written by Padre Agostino Manni, a disciple of San Filippo Neri.

6. See Carter, Jacopo Peri; Palisca, “The First Performance of Euridice”; Brown, “How Opera Began.” See also Brown’s introduction to his edition (1981) of Peri’s Euridice.

7. See Atti dell’accademia del R. Istituto musicale di Firenze; Solerti, Musica, ballo e drammatica; Ehrichs, Guilio Caccini; Strunk, ed., Source Readings (1950 ed.), 363–76; Hanning, Of Poetry and Music’s Power.

8. Since Peri’s Euridice was not a court-sponsored event, the official chronicler for the Medici was “forbidden to praise the opera at the expense of Il rapimento.” See Carter, Music in the Late Renaissance, 212; idem, “Non occorre nominare tanti musici: Private Patronage and Public Ceremony in Late Sixteenth-Century Florence.” After the initial performance, Euridice enjoyed considerable success; publications of the score occurred first in Florence (1601) and then in Venice (1608).

9. Poliziano’s Orfeo retains the tragic ending.

10. For a contemporary commentary upon the musicians who performed Peri’s Euridice, see Vincenzo Giustiniani, “Discorso sopra la musica de’ suoi tempi,” in Solerti, ed., Le origini del melodramma; for an English translation of the “Discorso,” see MacClintock, ed., Readings, 27–29. The introduction of the chitarrone slightly predates that of the tiorba, but by 1600 the words chitarrone and tiorba were often used interchangeably to refer to the same instrument. See, for example, the preface to Cavalieri’s La rappresentazione di Anima e di Corpo. Cf. Spencer, “Chitarrone, Theorbo, Archlute”; s.v. “Chitarrone” in The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 1:359–60; and Borgir, The Performance of the Basso Continuo in Italian Baroque Music.

11. On the figuring of the basses and their realization in the early monodists, see F. Arnold, The Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-Bass, chap. 1, secs. 5–8. See also Wellesz, “Die Aussetzung des Basso Continuo”; Goldschmidt, “Die Instrumentalbegleitung”; Borgir, The Performance of the Basso Continuo.

12. See Neumann, Die Aesthetik des Rezitativs.

13. Cf. Paoli, “Difesa del primo melodramma,” and Pirrotta, “Early Opera and Aria.”

14. Doni, “Trattato,” in his Lyra Barberina, chap. 29, and reprinted in Solerti, ed., Le origini del melodramma, chaps. 4–6.

15. Fundamental works on Monteverdi as an opera composer are those of Abert, Leopold, Fabbri, Redlich, Sartori, Schrade, and Arnold and Fortune, eds.

16. References to Monteverdi’s works will be to the complete edition (C.E.) by Malipiero: vol. 11, Orfeo; vol. 12, Il ritorno d’Ulisse; vol. 13, L’incoronazione di Poppea.

17. For a series of essays and a comprehensive bibliography (pre-1985) devoted specifically to this opera, see Whenham, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Orfeo. Facsimiles of the score as published by Amadino of Venice in 1609 and 1615 are also available.

18. Francesco Gonzaga, who commissioned Orfeo, and Alessandro Striggio, who wrote the libretto, were members of the Accademia degli Invaghiti; Monteverdi, however, was not a member. It is generally assumed that the production was staged at the ducal palace, but the precise location within the palace has not been confirmed. Recently discovered letters written on February 23,1607, offer new information about this event; one suggests the opera took place “in a room in the apartments of Margherita Gonzaga d’Este,” Francesco’s sister. For correspondence relating to performances of Orfeo at Mantua, see Fenlon, “The Mantuan Orfeo,” and appendix I in Whenham, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Orfeo. See also Besutti, “The ‘Sala degli Specchi’ Uncovered.’’

19. Fenlon, “The Mantuan Orfeo,” 171.

20. Authorship of the text for the last part of Act V (as it exists in the 1609 score) is unknown, but it is generally agreed that the style of writing is not of the same quality shown in Striggio’s works.

21. For more concerning the libretto of Orfeo, including a reprinting of Act V of Striggio’s libretto in Italian with English translation, see Whenham, ed., Claudio Monteverdi: Orfeo, chaps. 1–3.

22. Fenlon, “The Mantuan Orfeo,” 18.

23. To date, there is no evidence to support the idea that performances took place in Florence, Cremona, Milan, and Turin between 1607 and 1610. S.v. “Orfeo” in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.

24. The exact nature of all these instruments and of the various combinations is still open to discussion. See Goldschmidt, Studien, 1:132–38; Westrup, “Monteverdi and the Orchestra’’; Collaer, “L’orchestra di Claudio Monteverdi’’; Beat, “Monteverdi and the Opera Orchestra of His Time”; and Glover, “Solving the Musical Problems.”

25. See Weaver, “Sixteenth-Century Instrumentation,” and Pirrotta, with Povoledo, Music and Theatre,179.

26. See A. Abert, Claudio Monteverdi, and Heuss, Die Instrumental-Stücke des Orfeo (appendix 3).

27. See, for example, arias in Stefano Landi’s Sant’Alessio, and Francesco Cavalli’s Giasone.

28. Dramatically interesting laments were written by other composers of this period. For example, Sigismondo d’India (c. 1582–1629) wrote five laments that were published in 1621 and 1623.

29. To comply with Ferdinando Gonzaga’s request that Arianna be revived to celebrate Caterina de’Medici’s birthday on May 2, 1620, Monteverdi revised and recopied the score. Arianna, however, did not enjoy a revival that year, for Ferdinando changed his plans for the event.

30. Monteverdi’s letters reveal his displeasure with the Mantuan court. Not the least of his complaints concerned the irregular payment of his very modest stipend. See The Letters of Claudio Monteverdi, translated by Denis Stevens.

31. This Florentine academy, which included as members Peri, Rinuccini, and Bardi, was short lived, lasting only until 1609. See Strainchamps, “New Light on the Accademia degli Elevati of Florence.” See also Vogel, “Marco da Gagliano.”

32. Of the operas Gagliano wrote for this court, only La Flora survives. It was written some twenty years after Dafne and will be discussed in chapter five.

33. For an English translation of this preface, see MacClintock, ed., Readings in the History of Music in Performance.

34. Savage, “Prologue: Dafne Transformed.”