MARCO DA GAGLIANO called opera “the delight of the princes,” and for the first few decades of its existence, it was almost exclusively that.1 Indeed, up to the end of the eighteenth century some operas continued to be produced that were primarily for the delectation or glorification of rulers, nobles, or other wealthy patrons and only incidentally, if at all, for the entertainment of the public.

The Florentine court was, of course, one of the main centers for such operatic activity. Here the extravagant dramatic entertainments were designed to undergird the legitimacy of the rulers of Tuscany. Particularly interesting examples of this conscious effort to exalt those in the seat of power are to be found in the years 1621 to 1628, when Tuscany was co-ruled by the wife (Maria Maddalena) and the mother (Cristina) of the Grand Duke Cosimo II (1590–1621).2 In his will, Cosimo had made provision for the regency in the event his death occurred prior to the time when his son, the crown prince Ferdinando (1610–70), would be old enough to assume his rightful position as his successor.

During this seven-year period, Maria Maddalena encouraged the creation of literary, artistic, and dramatic works that dealt with women in positions of power, especially historical figures who had achieved significant political stature. By so doing, she sought to cultivate an atmosphere of respect for the regency. That the court’s librettists and composers were amenable to the arch-duchess’ ideas is evident from the fact that the lives of biblical women and female saints figure prominently in the theatrical entertainments presented during the regency. Some of these productions were intended for the private enjoyment of the ruling family; others were staged as entertainment for visiting dignitaries. Among the composers who contributed to sixteen musical spectacles that were staged in Florence between 1622 and 1628, all with female protagonists, were Marco da Gagliano, Giovanni Battista da Gagliano, Filippo Vitali, Jacopo Peri, and Francesca Caccini, the eldest daughter of Giulio Caccini.3

Francesca Caccini (1587–c.1640) served the Medici court as both a singer and a composer from 1600 to 1627 and again from 1634 to 1637. In the interim period she served other patrons, including several in Rome. Most of the music she composed no longer survives, an unfortunate loss in light of the fact that Francesca is acknowledged to be the first woman to have composed an opera. Documents indicate she was involved with at least three of the spectacles produced for the Florentine court, but the only one that is extant is La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (Carnival, 1625). The performance took place as part of the festivities that entertained Prince Władisłan of Poland when he visited Florence.4 A recent study of La liberazione di Ruggiero reveals a compositional scheme devised by Caccini to equate gender with tonality: flat keys are associated with the female protagonist, Alcina, and her attendants; sharp keys, with the male protagonist, Ruggiero, and the other supporting male roles; and the key of C, with the androgynous sorceress Melissa.5

On July 14, 1628, Ferdinando II became the new grand duke of Tuscany. Interestingly, the ending of the regency and the inauguration of a new era of government seemed to pass without any newsworthy court festivities, but several months later, the transition from female to male power found expression in La Flora, an opera presented at the Uffizi theater in conjunction with the celebration of the marriage of Ferdinando’s sister, Margherita, to Duke Odoardo Farnese of Parma. For this libretto, Andrea Salvadori retained the role of a strong female protagonist (Venus), a feature of librettos set to music during the regency, but he abandoned the biblical subjects in favor of nymphs, shepherds, gods, and goddesses. This return to the type of pastoral themes found in the librettos of the earliest Florentine operas was perhaps meant to recall the powerful Medici rulers of the past and, by extension, to demonstrate the continuity of that power with the restoration of a male to the seat of government.6 La Flora was set to music by Marco da Gagliano.7 It consists of a prologue and five acts, and was written in collaboration with Peri. His contribution is limited to the music for the title role sung by Chloris, who at the end of the opera becomes transformed into Flora (flowers).

La Flora is mentioned in Il corago, an anonymous treatise written at Florence in which the duties of the person in charge of a theatrical production are described in considerable detail.8 The corago was responsible not only for the mechanical aspects of a staged spectacle but also for the movement of the actors and singers on stage. Of special interest is the chapter that discusses the pace at which the gestures should be coordinated with the singing, cautioning that the movement of the hand should be slow enough so that it does not stop before the voice completes its vocal phrase. Similar cautionary remarks are given with respect to the movement of the singers on stage.

Rome

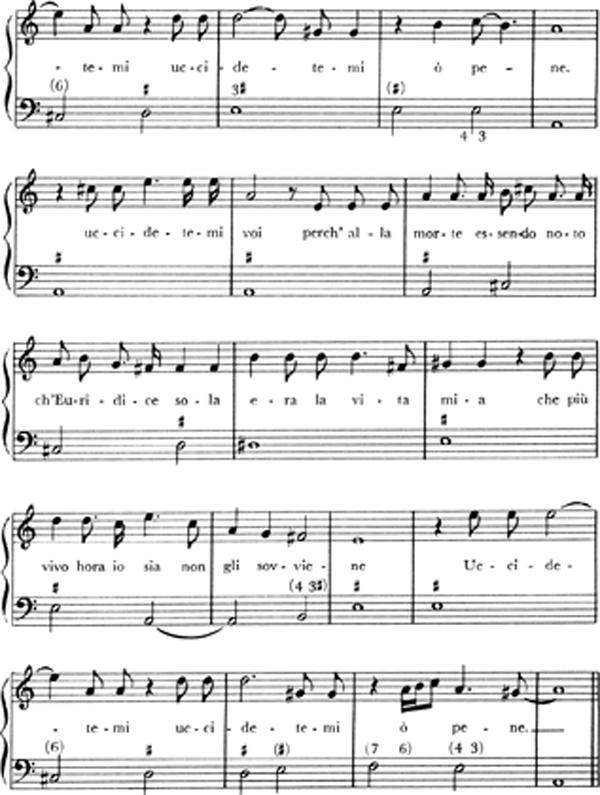

The majority of the Italian court operas composed between 1610 and 1650 appeared at Rome and, like the earliest operas at Florence and Mantua, were created as special events for festal occasions. Many of the scores were printed and have come down to us, so that this period of opera is fairly well known to historians.9 Moreover, the available financial resources permitted elaborate stage effects and a sufficiently large cast to allow for ballets and extensive musical ensembles. These ensembles—called “choruses,” though they were in reality madrigal-like pieces for a comparatively small group of singers—are characteristic of the so-called Roman opera of the early seventeenth century.

The new recitative style (recitar cantando) was introduced at Rome in February 1600 with Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s La rappresentazione di Anima e di Corpo.10 The text is based upon a lauda, “Anima mia che pensi.” In this sacred opera, Cavalieri uses the chorus more extensively than was done by Peri and Caccini in their operas. Several of the solo songs are not in the recitative style; they are distinctly tuneful and popular in character. Dances and instrumental interludes also occur. The score was published in 1600 and represents the earliest printed one with a figured basso continuo. Prior to the staging of La rappresentazione, Cavalieri (according to his own claims) had experimented with the monodic style in the music he contributed to several works performed for the Florentine court in 1590, 1595, and 1600. Unfortunately, none of this music has survived. Cavalieri’s style of composition eventually found a number of adherents in Rome, notably Agostino Agazzari (1578–c. 1640), Stefano Landi (c. 1586–1639), and Domenico Mazzocchi (1592–1665).

Agazzari, author of an important treatise on the thorough-bass, served briefly as maestro di cappella for the Collegio Germanico (1602–3) before accepting a similar appointment at the Seminario Romano, a Jesuit institution. For the pre-Lenten entertainment of students enrolled in this seminary, Agazzari composed Eumelio (1606), a dramma pastorale in three acts, entirely set to music. So successful was this production, it encouraged Jesuit institutions in Rome to use Latin operas and plays for educational purposes.11

One student who could have attended the 1606 performance of Eumelio was Stefano Landi, for he was enrolled at the Seminario Romano from 1602 to 1607.12 Landi’s appointment as maestro di cappella to the bishop of Padua in 1618 did not deter him from composing operas. His first work in this genre was La morte d’Orfeo (1619), which introduces large scene-complexes; they are carefully organized with solos and choral ensembles at the close of each act, with the largest one of all coming at the end of Act V.13 There had been scene-complexes of this sort, of course, in the Florentine Euridice operas and in Monteverdi’s Orfeo, but there they were essentially connected with the drama. In Landi’s La morte d’Orfeo and in other later operas at Rome, the big finales do not as a rule grow organically out of the plot but seem rather like intermedi, spectacular visual and vocal displays only loosely related to the action.

The leading patrons of opera at Rome were the powerful family of the Barberini, princes of the church. They included Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, an accomplished poet in his own right, who was elected to the papacy in 1623 as Urban VIII, and his nephews Cardinal Francesco Barberini, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, and Don Taddeo Barberini. Among the earliest surviving operas produced in Rome under their patronage are Filippo Vitali’s (c. 1590s–c. 1653) Aretusa (1620), Giacinto Cornacchioli’s (c. 1598–1673) Diana schernita (1629), Domenico Mazzocchi’s La catena d’Adone (1626), and Landi’s Il Sant’Alessio.

The first recorded performance of Sant’Alessio occurred on February 17, 1632, as entertainment for the Carnival season; two years later Landi prepared an extensively revised version of this opera.14 Both productions took place in large rooms within the Palazzo Barberini at the Quattro Fontane.15 Il Sant’Alessio was one of the most important operas of the Roman school and one of the first operas to be written about the life of a saint.16 The libretto for this sacred opera is based on the legend of the fifth-century St. Alexis, but the persons and scenes, both serious and comic, are obviously drawn from the contemporary life of seventeenth-century Rome. It was written by Giulio Rospigliosi (1600–69), friend of the Barberini family, distinguished man of letters, papal secretary, later cardinal, and finally pope under the name of Clement IX (1667–69).17 In addition to Il Sant’Alessio, Rospigliosi was responsible for writing all the other librettos for the stage works commissioned by the Barberini family.

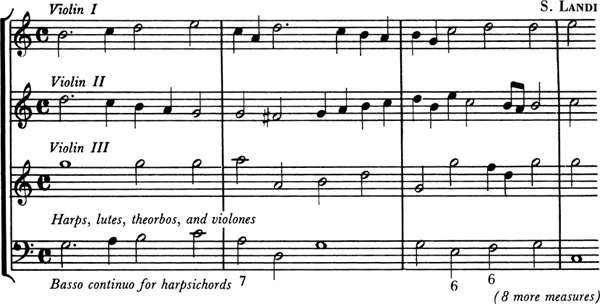

The opera is divided into a prologue and three acts, with its structural divisions clearly articulated by instrumental and choral numbers. The opera is introduced by a fairly long and well-developed orchestral sinfonia consisting of a solid chordal introduction, evidently in slow tempo (example 5.1), followed by a canzona (example 5.2). The canzona continues for sixty measures in contrapuntal style to the end, with the exception of one more homophonic section consisting of alternating forte and piano phrases and one interlude in the rhythm of a saraband, in strict note-against-note writing.18 The piece is then brought to a close with a stretto-like passage in eighth notes and a final broad cadence in G major.19 The formal resemblance of this canzona overture to the later sonata da chiesa is obvious, and it has further historical importance as being the model for the type of “French overture” perfected about thirty years later by Lully. The prelude to the second act of Sant’Alessio is likewise a canzona in three movements but without a slow introduction, thus giving it a superficial resemblance to the later “Italian overture” pattern (fast-slow-fast). In the orchestra of Sant’Alessio, the old-fashioned viols are replaced throughout by violins (in three parts) and violoncellos. Harps, lutes, and theorbos play for the most part with the strings, but the harpsichords have a separate staff in many of the instrumental numbers. It will be noted that the outlines of the modern orchestra are here distinct; only the number and variety of “fundament” instruments remind us of the earlier practice, and these will remain in the orchestra, though in decreasing numbers, until the time of Haydn and Mozart. The wind and percussion instruments will become from now on ever less conspicuous, being used in opera primarily for special effects or in full subordination to the string group.

Scene from Sant’Alessio by Stefano Landi, presented at Rome in 1634.

EXAMPLE 5.1 Il Sant’Alessio

EXAMPLE 5.2 Il Sant’Alessio

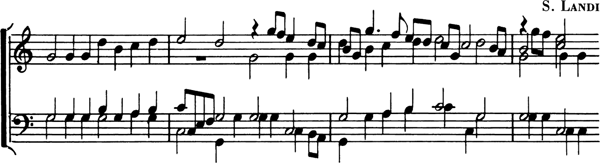

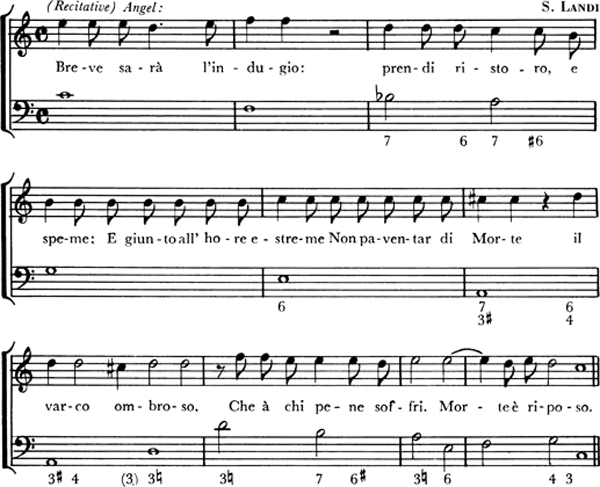

The vocal writing in Sant’Alessio shows signs of moving away from the early Florentine operas. The many repeated notes and frequent cadences in the recitatives (example 5.3) are characteristic features of a later style. There are few distinct solo arias, but many ensemble and choral scenes, among which the finale of the last act is particularly impressive.

EXAMPLE 5.3 Sant’Alessio, Act II, scene vii

The extremely high range of Alessio’s part is typical of many roles in early seventeenth-century opera for male sopranos. Such singers, called castrati, had first appeared in some of the earliest Florentine operas. Despite efforts to abolish the custom, it became increasingly prevalent during the seventeenth century, most notably in Italy. Castrati sang not only female roles, especially in those cities where there was a papal ban on women appearing on stage, but also male roles in Italian opera seria.20

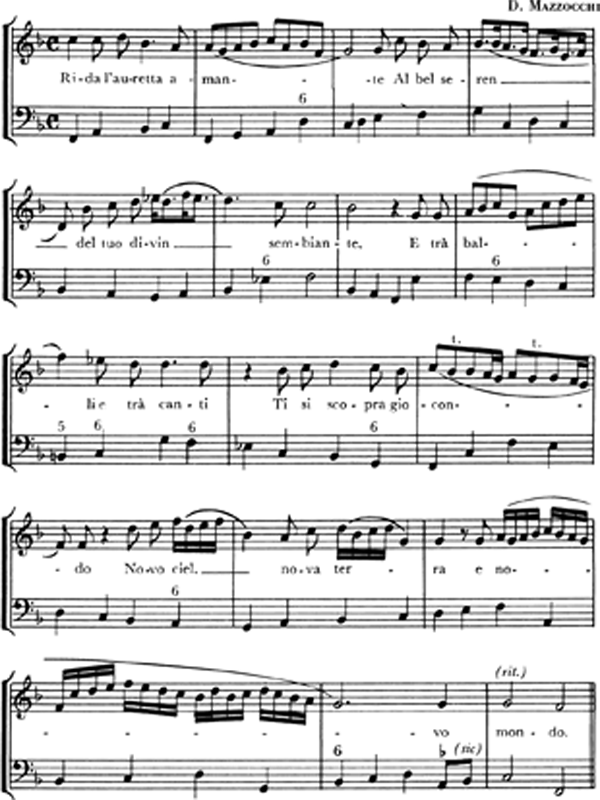

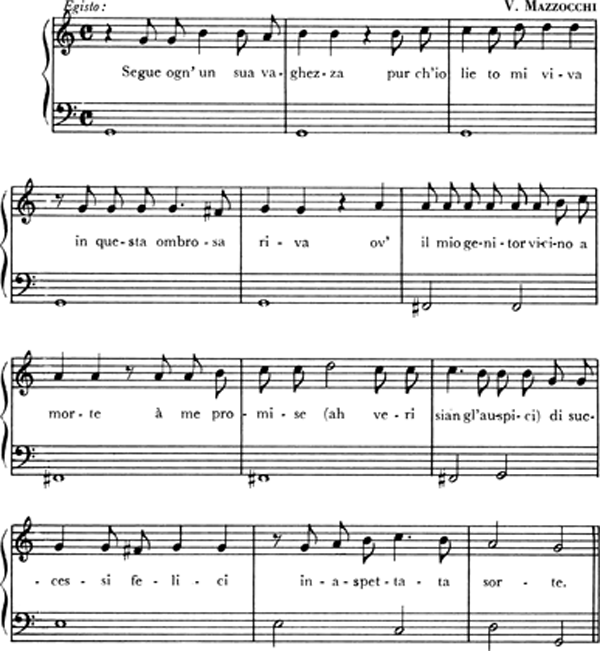

Still further departure from the Florentine ideal is evident in Domenico Mazzocchi’s La catena d’Adone.21 The libretto, based on an episode in Marino’s epic Adone, tells the story of the rescue of Adonis by Venus from the wiles of the enchantress Falsirena. According to the “allegory” printed at the end of the score, this is supposed to symbolize the rescue of man by heavenly grace from the bonds of sensuality and error. The libretto also embraced at least one other level of symbolism, for it played upon the rivalry that existed between the two leading female singers. The various mythological personages on the stage are no longer the statuesque and serious figures of early Florentine opera but conduct themselves like characters in a bedroom farce; the complicated intrigue is bolstered by all kinds of magic tricks and particularly by the use of disguises—credulity in this respect knowing no bounds in opera from this early day to the present—and by sudden transformations of scene, conjurations, descents of gods, and the familiar pastoral background. The typical later Baroque opera plot, with its multitude of characters, fantastic scenes, and incongruous episodes, is already foreshadowed in this work.

Musically, La catena d’Adone is important for its many vocal ensembles and also for its embryonic line of demarcation between monodic recitatives and songs of a more definite melodic profile and musical form. The term aria appears for the first time in the history of opera in this score, being applied, however, not only to solo songs but also to duets and larger ensembles. Some of the solo arias are hardly different from the monodic recitatives; others, however, are organized into clear-cut sections with distinct melodic contours. An aria of Falsirena in the finale of Act I, over a bass in steady movement of quarter notes (“walking bass”), introduces coloratura passages for the expression of joy (example 5.4).

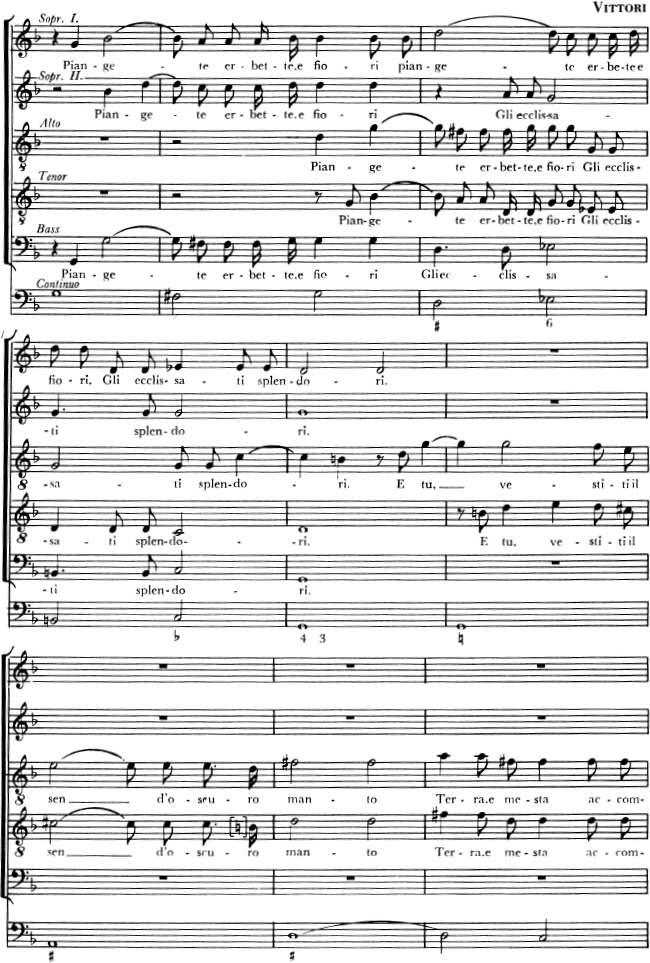

One of the castrato roles in La catena d’Adone was sung by Loreto Vittori (c. 1600–1670), a papal court singer and composer who in 1643 also became an ordained priest.22 Vittori was associated with Cardinal Antonio Barberini, to whom he dedicated the only surviving example of his dramatic work, La Galatea (1639).23 This Italian pastoral opera, one of the last from this period, has both text and music written by the composer. Musically, La Galatea is a superior work and was recognized as such by several eighteenth-century music historians, including Andrea Adami and Charles Burney. Later writers also championed its merits. Romain Rolland called La Galatea “the finest lyric drama of the first half of the seventeenth century,” and Francesco Vatielli considered the last act to be “un vero capolavoro per nobiltà d’espressione e per grandiosità di disegno” (a true masterpiece for its nobility of expression and grandeur of design).24 The arias show progress in the direction of formal organization based on a clear system of tonal relationships; the recitatives include occasional expressive dissonances but for the most part tend toward the semplice style. Some of the finest music of this opera is found in the lament “Pur mi lasci crudele” sung by Acis (Act III, scene i) and in its ensembles (example 5.5).

EXAMPLE 5.4 Aria from La catena d’Adone, Act I, scene iii

Conditions at Rome on the whole did not favor the growth of serious opera on secular themes. The influence of the church tended rather to the cultivation of the oratorio or similar quasi-dramatic forms, or at most permitted operas of a pious allegorical or moralizing nature, such as Sant’Alessio (already described); L’innocenza difesa (1641) and Il Sant’Eustachio (1643) by Virgilio Mazzocchi (1597–1646);25 and La vita humana ovvero Il trionfo della Pietà (1656) by Marco Marazzoli (c. 1605–62), one of the last operas to be produced at the Palazzo Barberini theater.26 Secular productions were represented chiefly by the harmless, diverting genre of the pastorale, of which Loreto Vittori’s La Galatea and Michelangelo Rossi’s (c. 1601–56) Erminia sul Giordano are prime examples.

Erminia sul Giordano was performed during Carnival in a room at the Palazzo Barberini in 1633. Rospigliosi’s libretto for this pastoral opera is based on the sixth and seventh cantos of Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata, with episodes from other parts of the poem. The plot revolves around mistaken and unfulfilled love and the juxtaposition of pagan and Christian themes, such as the pagan Erminia’s love for the Christian Tancred.27 The opera’s musical interest is concentrated in the choruses, which include a hunting chorus with echo effects and a chorus of soldiers on a trumpet-like motif to the words “All’armi.” Erminia consists of an imperfectly connected series of scenes with elaborate stage settings and machines, a feature of the Barberini productions.

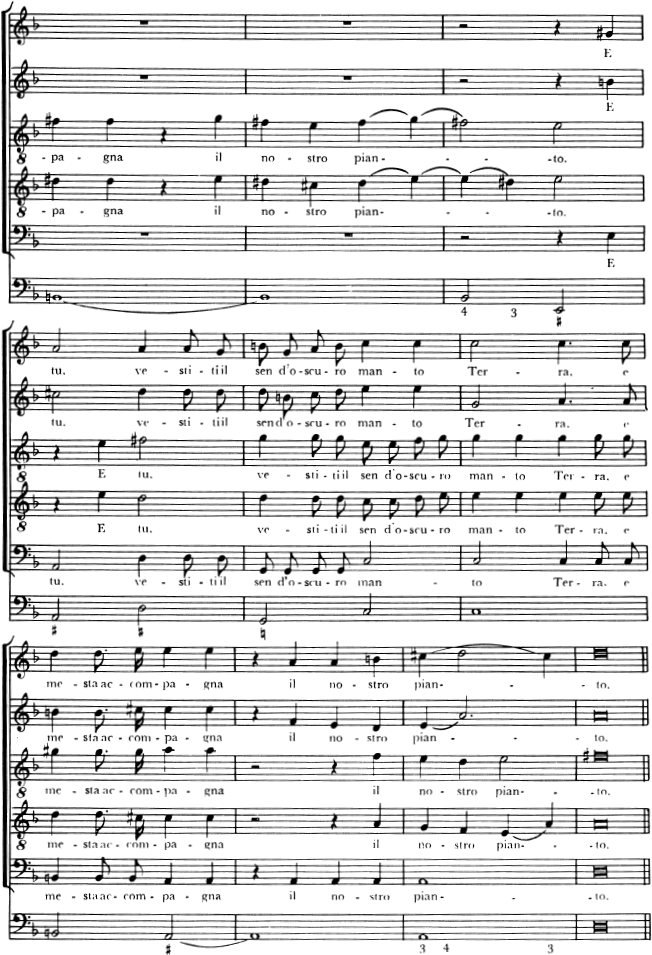

The last important Roman composer of serious opera in this period was Luigi Rossi (c. 1597–1653), a singer who also composed oratorios and more than four hundred cantatas and songs. Only two operas by Rossi are known.28 His first opera, Il palazzo incantato, is based on a libretto by Rospigliosi; it was commissioned by Cardinal Antonio Barberini for the 1642 Carnival season and performed at the Palazzo Barberini theater.29 The prologue is sung by four allegorical figures—Magic, Music, Painting, and Poetry—who describe the process of staging a dramatic work. Music and Poetry scold Painting for not completing the scene designs on time, a task that Magic is called upon to accomplish. For this she is rewarded with an opportunity to select the subject of the opera: an episode from Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, which has as its underlying theme “loyalty with valor.”

EXAMPLE 5.5 La Galatea, Act III, scene iii

Rossi’s second opera, Orfeo, was given in Italian at Paris in 1647. This production was the consequence of political changes at Rome resulting in the election of Pope Innocent X in 1644, which forced the Barberini family to emigrate. At the invitation of Cardinal Mazarin, the Barberinis relocated to Paris, taking with them Rossi and many other musicians in order to give the French a taste of Italian opera.30 The poem of Orfeo, though based faithfully on the ancient myth, introduces several more or less irrelevant episodes, resulting in a hodgepodge of serious and comic scenes intermingled with ballets and spectacular stage effects. The only way a composer can deal with such a libretto is to ignore the drama (or lack of it) and concentrate on the musical opportunities offered by each scene.

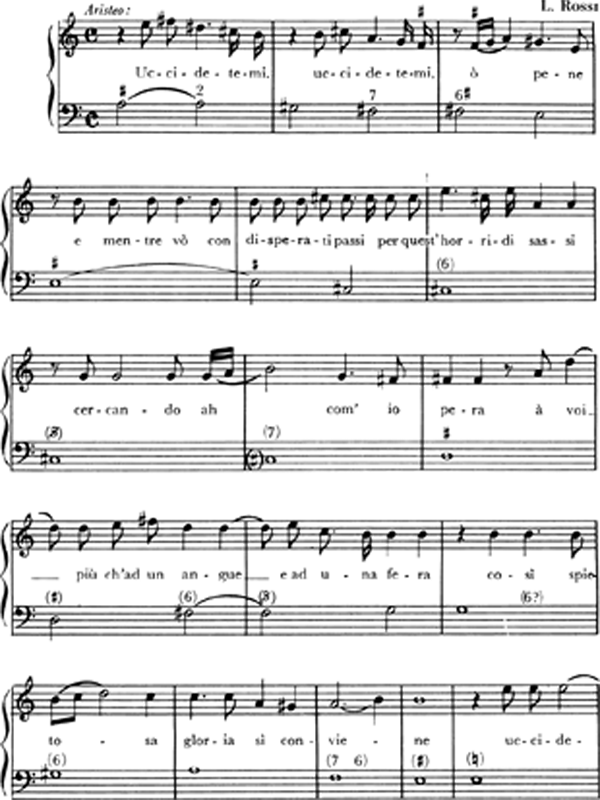

The score of Orfeo is as variegated as its poem, and it is especially remarkable as being one of the first operas in which the arias outnumber the recitatives. There are strophic arias over an ostinato bass, two-part arias, buffo (comic) arias, and da capo arias, as well as many ensembles of different kinds. The music is distinguished by that grace and perfection of style, that refinement of sensuous effect, for which its composer, along with Carissimi and Cesti, was so greatly admired in the seventeenth century. Eurydice’s aria “Mio ben” in Act II is an excellent example of a lament, with long-breathed, mournful coloraturas streaming above a repeated descending bass figure. Another lament, in Act III, is built like the celebrated one from Monteverdi’s Arianna, in an expressive monodic recitative with a refrain—slightly varied at each recurrence—on the words “Uccidetemi, o pene” (Kill me, O sorrows; see example 5.6).

With all its beauty of detail, however, Rossi’s Orfeo as a whole is no more a dramatic entity than Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust; it is a succession of lyrical and scenic moments in which the beauty of the music and decor successfully conceals the absence of any serious dramatic purpose. As such, it illustrates the extent to which opera in the course of forty years had moved away from the early Florentine ideal in the direction of the formal exterior of the later Baroque opera.

EXAMPLE 5.6 Orfeo, Act III, scene iii

The First Comic Operas

Italian popular comedy at this period was represented by the commedia dell’arte, which found its musical counterpart in the madrigal comedies of Vecchi and Banchieri. It is in the Italian pastorales that comic episodes begin to appear. The scenes in Landi’s La morte d’Orfeo, for example, are of the sort common to other Italian pastorales. Sant’Alessio, one of the first operas to be written about the inner life of a human character, is not without its comic episodes, most notably a duet of ridicule sung by the pages. Here the pages and the nurse represent more realistic comic characters, obviously patterned after the stock characters of the commedia dell’arte.

The creation of comic opera, the foundation of the long Italian opera buffa tradition that was to culminate in Mozart and Rossini, was the work of Giulio Rospigliosi. In addition to his opera poems already cited (Sant’Alessio, Il palazzo incantato, Erminia sul Giordano), Rospigliosi wrote several others, including comic intermedi and two highly successful comedies: Chi soffre speri and Dal male il bene.31 Chi soffre speri (also known as L’Egisto) was performed at the Palazzo Barberini in 1637 and again in 1639 in a revised version.32 It is generally agreed that the second version (the only one of which the music is now known) represents the musical collaboration of Virgilio Mazzocchi and Marco Marazzoli. Although the extent of that collaboration is open to question, Marazzoli usually is credited at the very least with the composition of La fiera di Farfa, the intermedio for Act II.33

Chi soffre speri is based on a story by Boccaccio. It has a romantic plot, with scenes featuring character types of the commedia dell’arte and similar figures from the common walks of Italian life, in the manner established by Michelangelo Buonarroti with his comedies La Tancia (1612) and La Fiera (1618) and already used by Rospigliosi in his own poem Sant’Alessio. The use of dialect by the comic characters may have been patterned after an earlier opera by Angelo Cecchini (1619–39) that was produced in Rome in 1635.34 The dialogue of Chi soffre speri is conveyed in a kind of recitative that differs essentially from the quasi-melodic monody of the Florentines; it is the style that later came to be called recitativo semplice or recitativo secco: a quick-moving, narrow-ranged, sharply accented, irregularly punctuated, semi-musical speech, with many repeated notes sustained only by occasional chords—a style for which the Italian language alone is perfectly adapted and that has always been a familiar feature of Italian opera.35 Although tendencies toward this type of recitative were manifest in earlier Roman works, the necessity of finding a musical setting for realistic comic dialogue led to its fuller development, as seen in example 5.7.

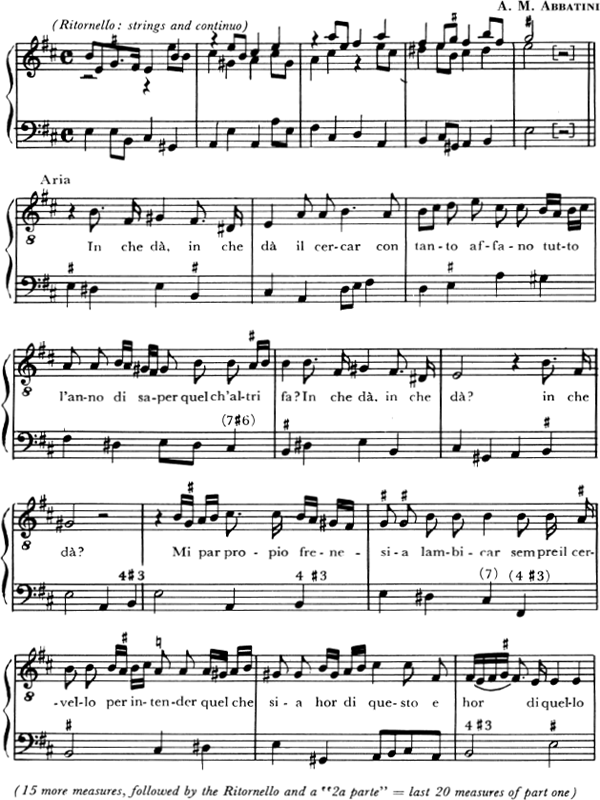

Apart from the recitative and one lively ensemble scene in an intermedio (depicting the bustle of a fair), the score of Chi soffre speri is surpassed in quality of both libretto and songs by Dal male il bene. This comic opera, with music by Antonio Maria Abbatini (c. 1609–79) and Marco Marazzoli, was performed in 1653 to mark the return of the Barberini to Rome and the subsequent reopening of the Palazzo Barberini theater.36 It also marked the celebration of Maffeo Barberini’s marriage to Olimpia Giustinani. Rospigliosi, who had served as papal legate in Madrid from 1646 to 1653, showed in the construction of his libretto some influence of the Spanish playwright Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600–1681), especially the latter’s La dama duende (1629). Dal male il bene is a romantic comedy in which, after complications and misunderstandings, two pairs of lovers are happily united. The servant characters are evidently drawn from life, except for one of them, the comic servant Tabacco, who is obviously taken over from the commedia dell’arte masks. Incidentally, this character type appears again and again in operas of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; Leporello in Mozart’s Don Giovanni is probably the most familiar example. The music of Dal male il bene is notable for the skill of the recitatives and for another feature that later became characteristic of the opera buffa—namely the solo ensembles, especially the trio at the end of Act I and the sextet, which forms the finale of the opera. Tabacco’s aria “In che dà?” from Act I shows a well-developed tonal and formal scheme, together with a good sense of comic style (example 5.8).

Mozart’s Don Giovanni was also foreshadowed by a production at Rome of L’empio punito (1669), the earliest known operatic portrayal of the myth of Don Giovanni.37 This opera, with libretto by Filippo Acciaiuoli and music by Alessandro Melani (1639–1703), was staged at a semipublic theater and sponsored by Queen Christina of Sweden during her sojourn in Rome.38 The plot contains many of the same components found in Da Ponte’s version of the myth: the two pairs of lovers; a host of female acquaintances who are the object of Acrimante’s amorous escapades; the comic servant Bibi, who faithfully accompanies his master; the exchange of clothing that causes mistaken identities (Bibi asks to borrow Acrimante’s cloak so he will present a more dapper image before the servant Delfa); Acrimante’s mocking of Tidemo’s statue, after having killed him in a duel; an invitation issued to the statue to attend a banquet; and the demise of Acrimante, as he gives his hand to Tidemo and is ferried away to the underworld by Charon in his barque.

EXAMPLE 5.7 Chi soffre speri, Act I, scene i

EXAMPLE 5.8 Dal male il bene, Act I, scene vii

Alessandro’s position as a church musician in Rome reveals itself in this opera, for here there are brief choral passages interjected into the flow of recitatives and arias. These choral interjections, considered somewhat unusual for operas of this period, include the chorus of stable boys in Act I and the chorus of demons that appears to Acrimante in a dream.39 Although the basso continuo accompaniment predominates throughout the score, there are nevertheless a substantial number of arias that are accompanied by a three-part string ensemble—two violins and continuo (chitarrone and harpsichord).

At the time Melani composed L’empio punito, he and his older brother, Jacopo Melani (1623–76), were living in Rome, having moved there in 1667. The following year Jacopo achieved considerable success with his comic opera Il Girello (1668), which has a prologue by Alessandro Stradella. This political satire was instrumental in launching a new phase of comic opera production in Rome. Prior to his arrival in Rome, Jacopo had been acclaimed for his comic operas produced at Florence between 1657 and 1662 by the Accademia degli Immobile, a dramaturgical society made up of aristocratic personages. Of these operas, only one survives; it is Il podestà di Colognole (1657), with libretto by Giovanni Andrea Moniglia.40 The performance of this excellent work is noteworthy because it makes clear that comic opera productions were no longer exclusively associated with Rome.41 In fact, almost all Moniglia’s comic librettos were written for a Florentine audience. II podestà contains many more arias in proportion to recitatives than did earlier comic works, and it is possible to observe some of the standardized forms into which the aria, in both serious and comic opera, was settling down during the latter half of the seventeenth century. These forms divide themselves, with few exceptions, into three groups:

1. Strophic songs. The solo part may be either literally repeated for each stanza or more or less varied. The style in many of these is light and simple, frequently showing traces of popular song-types or dance meters. Others are more serious in mood. There is usually an orchestral ritornello or a short section of recitative between the stanzas (example: Tancia’s “S’io miro il volto,” Act I, scene ix).42

2. Through-composed arias. These occur in a wide variety of types, both serious and comic, but all have a broader formal pattern and are less regular in melodic and rhythmic structure than the strophic songs. They consist of a number of sections, each ending with a full cadence in the tonic or a related key, and separated by orchestral ritornellos (examples: Isabella’s “Son le piume acuti strali,” Act I, scene i; Leandro’s “Sovra il banco di speranza,” Act I, scene viii).43 The basic form of these arias is two-part, without marked contrast of thematic material. Sometimes, however, the second section may be more contrasting, followed by a repetition of the first, resulting in a three-part form (example: Lisa’s “Se d’amore un cor legato,” Act I, scene i).44

Arias of this second group represent the main channel of development of operatic style in the later seventeenth century. In the course of time, the formal scheme is expanded, the orchestra enters into the accompaniment proper as well as at the ritornellos, concertizing instruments appear, a fully developed da capo form gradually replaces the simple two-part structure, and eventually a number of stereotypes develop—arias of definite categories, each distinguished by certain stylistic procedures and appearing in the opera in a more or less rigidly fixed order of succession. This final degree of stylization, however, is not achieved until the early part of the eighteenth century.

3. Arias over an ostinato bass. Most arias of this group are serious in mood and belong to a recognized type known as the lament (example: Isabella’s “Lungi la vostra sfera,” Act I, scene xx).45 They are most often in triple meter, with slow tempo, and the usual bass figure is the passacaglia theme consisting of a diatonic or chromatic stepwise descent of a fourth from the tonic to the dominant, or some variant of this.46

By the middle of the seventeenth century, opera had come a long way from its beginnings as a pastoral play with monodic singing based on a supposed imitation of ancient Greek drama. Extensive ensemble numbers, typical of the earliest operas, survived after 1650 only in works destined for special aristocratic or state occasions. More significant historically, therefore, were the steps taken in the early seventeenth century toward establishing the main outlines of the structure of opera as a whole, founded on the separation of recitative from aria and the working out of musical forms for the latter, with distinct tonal relationships. Along with this formal progress went the discovery of new types of expression: the comic opera began its career with its recitativo semplice and solo ensemble numbers; serious opera explored the possibility of successful musical treatment of subject matter other than the conventional pastorale, as demonstrated by Rospigliosi and Landi. Finally, the modern orchestra, centering around violin instruments and continuo, was established, and an important type of overture originated. Changes already begun in the first few decades were accelerated as opera moved out of the shelter of aristocratic salons onto the stage of public theaters.

1. Gagliano’s remarks can be found in the preface to his Dafne

2. For a particularly informative article on the regency, see Harness, “La Flora and the End of Female Rule in Tuscany.”

3. Ibid., 446–48, for a chart of these theatrical works, listing composer, librettist, place of performance, and the female protagonist.

4. The production so delighted the prince that he commissioned Francesca to compose two operas for his court. Possibly the two she composed in 1626, which are no longer extant, fulfilled this commission.

5. Cusick, “Of Women, Music, and Power:A Model from Seicento Florence.”

6. It is no mere coincidence that the single-point perspective of the scenic design of this period converged at the very point where the Medici family were seated on a raised platform, centered directly in front of the stage—a symbolic expression of the ruler’s dominance in matters theatrical. On the relationship between political power and theatrical imagery, see Strong, Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals, 1450–1650, and Aercke, Gods of Play: Baroque Festive Performances as Rhetorical Discourse.

7. During the regency, Gagliano composed at least one other operatic work with Salvadori, La regina Sant’Orsola (1624), but the music has not survived.

8. The writing of Il corago, o vero alcune osservazioni per metter bene in scena le composizioni drammatiche has been attributed to Pierfrancesco Rinuccini, the son of Ottavio Rinuccini. Although the treatise is not dated, there are several internal clues that suggest it was written after 1628 and before 1637. Four of the twenty-three chapters of this treatise are translated and discussed in Savage and Sansone, “Il corago and the Staging of Early Opera.” The role of the Italian corago is related to the Greek choregos. See chapter one.

9. See, in particular, Murata, Operas for the Papal Court, 1631–1668, and Hammond, Music and Spectacle in Baroque Rome.

10. Kirkendale, who has written extensively about this composer and his era, calls attention to the fact that the performance of La rappresentazione before the entire college of cardinals constituted “the major musical event of the Holy Year 1600.” See, for example, chap. IX of his Emilio de’ Cavalieri “gentiluomo romano”: His Life and Letters.

11. See Culley, Jesuits and Music: A Study of the Musicians Connected with the German College in Rome, and Bjurström, “Baroque Theater and the Jesuits.” Eumelio was published in Venice in 1606.

12. See Carfagno, “The Life and Dramatic Music of Stefano Landi,” and Leopold, Stefano Landi.

13. Grout, “The Chorus in Early Opera.”

14. Although Il Sant’Alessio was composed in 1631, there is no record of its production that year. There is evidence, however, that the original score underwent some revision before a 1632 performance. See Hammond, Music & Spectacle in Baroque Rome, 202. For illustrations of engravings of the stage sets for the 1634 production, see Hammond, 211–12, and The New Grove Dictionary of Music (1980) 13:622.

15. The building of a theater for the Quattro Fontane palace (with a capacity of more than three thousand) did not occur until 1639.

16. As early as 1625, Sigismondo d’India’s opera on the life of a saint, Sant’Eustachio, was performed at Rome, but the score is no longer extant. Virgilio Mazzocchi’s Sant’Eustachio dates from 1643.

17. See Ademollo, I teatri di Roma; Salza, “Drammi inediti di Giulio Rospigliosi”; Pastor, History of the Popes, 31: 314–37; Murata, Operas for the Papal Court, 1631–1668.

18. Colin Timms, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music (1980), 10:425–28, has suggested that the sinfonias in this opera are “the first real ‘overtures’ in the history of opera.”

19. The overture to Francesca Caccini’s La liberazione di Ruggiero (1625) begins with a theme in canzona rhythm but does not have the fugal entrances. An overture similar to that of Sant’Alessio is M. Rossi’s “sinfonia” to Erminia sul Giodano (1633). See DeLage, “The Overture in Seventeenth-Century Italian Opera.”

20. Castrato roles continued to be present in operas for almost two hundred years. Late examples include Idomeneo (1781) and La clemenza di Tito (1791) by Mozart, and Traiano in Dacia (1807) by Giuseppe Niccolini (1762–1842). See Heriot, The Castrati in Opera; Rosselli, “The Castrati as a Professional Group and a Social Phenomenon, 1550–1850”; Bergeron, “The Castrato in History.”

21. This is the one surviving opera by D. Mazzocchi. See Witzenmann, “Domenico Mazzocchi,1592–1665.”

22. Vittori sang the castrato roles in many operas, including Luigi Rossi’s Il palazzo incantato. See Rau, Loreto Vittori; Antolini, “La carriera di cantante e compositore di Loreto Vittori.”

23. La Galatea was published in 1639 at Rome, but there is no record of its performance there. A production did take place, however, at Naples in 1644. Vittori created another version of this opera in 1655, with the most significant changes occurring in the finale to Act II.

24. The quotation from Rolland can be found in his “L’Opéra au XVIIe siècle en Italie.” The quotation from Vatielli can be found in an article by him, published in Rivista musicale italiana (1939), and reprinted in Loewenberg, Annals of Opera, vol. I, col. 17.

25. Virgilio was the brother of Domenico Mazzocchi.

26. Marco Marazzoli was not only a composer but also a singer and virtuoso harpist. For more on this opera, see Witzenmann, “Die römische Barockoper La vita humana.”

27. A similar juxtaposition of pagan and Christian elements pervades Rospigliosi’s Teodora (1635), an opera produced in Rome with music (now lost) by either Virgilio Mazzocchi or Stefano Landi.

28. See Ghislanzoni, Luigi Rossi, which contains an analysis of these two operas, with many short musical examples.

29. In some sources, this work is entitled Il palazzo d’Atlante. See Prunières, “Les Représentations du Palazzo d’Atlante.”

30. Rolland, Musiciens d’autrefois, 55–105, and Goldschmidt, Studien, 1:295–311.

31. Rospigliosi wrote the libretto for San Bonifatio (1638), an opera by Virgilio Mazzocchi that included comic scenes. Little of the text survives and even less of the music, with the only extant portion limited to Mazzocchi’s music for the intermedio, La civetta. This opera was well received and had additional performances in Rome, including four during Carnival of 1639. The composer took one of the singing roles.

32. A visitor who wanted to attend an operatic production in Rome usually was given an invitation, as was John Milton, who was among the invited guests for the 1639 production of Chi soffre speri. See Hammond, Music & Spectacle in Baroque Rome, 202.

33. See Reiner, “Collaboration in Chi soffre speri,” and “Mazzocchi, V.” in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.

34. This opera was Primavera urbana col trionfo d’Amor pudico (Rome, 1635). The score is lost, but the libretto by Ottaviano Castelli survives.

35. For a discussion of the terms recitativo semplice and recitativo secco, see Monson, “Semplice o secco: Continuo Declamation in Early 18th-Century Italian Recitative.”

36. The exact contribution of each composer is not entirely clear; usually Acts I and III are attributed to Abbatini and Act II, to Marazzoli. Cf. Witzenmann, “Die römische Barockoper,” and Holmes, “Comedy—Opera—Comic Opera.”

37. For an informative study relating to the Don Giovanni myth and its impact on the history of opera, see Pirrotta, Don Giovanni’s Progress.

38. The opening of Rome’s first public theater, the Teatro Tordinona, did not occur until 1671.

39. See Pirrotta, Don Giovanni’s Progress, 31.

40. Also known as La Tancia, overo il podestà di Colognole.

41. See Weaver, “Florentine Comic Operas.”

42. Goldschmidt, Studien, 1:357.

43. Ibid., 1:349, 355.

44. Ibid., 1:352.

45. Ibid., 1:360

46. A familiar example of this kind of aria is Dido’s lament, “When I am laid in earth,” from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas.