THE EARLY HISTORY OF OPERA in Germany is not one of a comparatively unified development, as in France or England, or even of the evolution of a comparatively consistent musical style, as in Italy. The numerous political subdivisions of Germany in the seventeenth century, the many different cultural traditions, the conflicting elements in both the dramatic and the musical background, and the extremely strong infusion of foreign styles (chiefly Italian, but some French) to different degrees in different parts of the country—all combine to produce a complicated task for the historian.

Abstractly speaking, a purely “German” opera is one written for performance by German artists for German audiences, with an original libretto in the German language and on a German (or, at least, not a typically foreign) subject, composed by a German, and with music in a German (or, at least, not predominantly foreign) style. In actuality, there are few, if any, operas of the early period that correspond to this admittedly narrow definition. What we find are foreign conductors and singers performing before German courts whose tastes are often formed on Italian and French models; librettos in Italian or in German translations or paraphrases of Italian or French texts; Italian composers, or German composers aping the Italian manner; and all possible permutations and combinations of these elements. Add to these conditions the fact that many composers were active in different places; that frequently the same opera poem appeared under different names, and different poems under the same name; that composers habitually used music from their own earlier works or inserted in their scores music from other sources; and finally that the scores themselves, a study of which alone could resolve many of the problems, are in the great majority of cases utterly lost or survive only in fragments—and it will be readily seen that a complete history of German opera in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries is, if not quite impossible, at least far beyond the scope of the present work. It has seemed best, therefore, to begin this chapter with a brief survey of the political and social conditions under which German opera was composed and of the dramatic and musical factors that entered into it, to indicate some of the principal developments at important centers, and then to concentrate on the most distinctive of the many local schools, that of Hamburg.1

In the seventeenth century, Germany was not a nation but a loose confederation of some seventeen hundred more or less independent states. Most of these were petty “knights’ dominions,” but there were also fifty-one free imperial cities (of which the chief were Hamburg, Bremen, Frankfurt am Main, Nuremberg, Augsburg, Ulm, and Strassburg), sixty-three ecclesiastical holdings, and nearly two hundred secular principalities and counties, a few of which were of considerable size and importance. The semblance of unity arising from an ill-defined allegiance to the Holy Roman Empire was disrupted by the Thirty Years War (1618–48), a calamity that left the country economically prostrated and bereft of almost all pride in its national heritage. Like a body weakened by illness, German culture was invaded by foreign elements. The language became filled with French and Spanish words; French became the common tongue of polite society; the little local courts, narrow, paternalistic, and extravagant, aspired to imitate the glories of Versailles.2 Italian opera thus made its appearance as a courtly show, particularly in southern Germany, where we have already seen some of its manifestations at Vienna, Dresden, Munich, Hanover, and Düsseldorf.

The German equivalent of the term opera was Singspiel, a literal translation of the Italian dramma per musica.3 Ayrer’s comedies on popular song-tunes at Nuremberg (from 1598) bear the designation singets Spil; the first operas at Hamburg were called Sing-Spiele. The term was applied in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries both to works sung in their entirety and to those having some spoken dialogue. In the second half of the eighteenth century, its meaning was restricted to works of the latter type. (It may be added that, in the absence of scores, it is not always possible to ascertain in the case of some seventeenth-century German operas whether the recitatives were sung or spoken.) The word opera does not often occur in German scores before 1720.4

Many courts tried at first to encourage German talent. For example, the “first German opera,” Dafne, was created and performed in Torgau in 1627 to celebrate the marriage of Princess Luise of Saxony and Landgraf Georg von Hessen-Darmstadt. This work was the old Dafne of Rinuccini, translated and adapted by the leading German poet of the time, Martin Opitz, with music by Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672). The score has not survived. In Vienna, the early Italian operas occasionally had German songs inserted. Dresden also staged a few works in German before the establishment of the Italian opera company in the 1680s.5 One of these, another Dafne (1671), with music by Giovanni Angelini-Bontempi and Marco Peranda (1625–75), is the earliest German opera for which the full score is extant.6

New theaters that could accommodate opera productions were opened in a number of German cities during the second half of the seventeenth century, including Innsbruck (1654), Dresden (1667), Breslau (1677), and Düsseldorf (1695). In Munich, an opera house fashioned from an abandoned granary was inaugurated in 1657 with a production of Johann Caspar Kerll’s (1627–93) Orontea. Three opera houses, all with free admission, were opened in Hanover between 1678 and 1690.

At Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel the court opera employed native poets, subjects, and composers (Erlebach, Krieger, Bronner, Kusser, Keiser), but with the opening of a public theater in 1690, the demand for foreign goods became so strong that French and Italian works had to be added to the repertoire. A temporary revival of native opera in the early eighteenth century was led by Georg Caspar Schürmann (c. 1672–1751), one of the most significant of the German composers, whose dignified, serious musical style has much in common with that of Keiser, Handel, and J. S. Bach. Between 1700 and 1730, he composed about forty operas, including Endimione (1700), the sacred operas Salomon (1701) and David (1701), and Ludwig der Fromme (1726), considered to be Schürmann’s chief work in this genre.7 Few of his opera scores have been preserved.

At Leipzig, an opera house was founded by Nikolaus Adam Strungk (1640–1700), opening in 1693 with a performance of his Alceste. Here, where operas were played during the Fair season from 1693 to 1720, the texts were mostly translations of Venetian librettos. Poets and composers, players and singers were largely recruited from the students of the school of St. Thomas’s church, and so successfully that Johann Kuhnau (1660–1722) in 1709 complained that church music suffered from the competition.8 The general enthusiasm for opera at Leipzig was such that even J. S. Bach did not altogether escape its influence.9 Another center of German opera was Weissenfels; here the leading composer was Johann Philipp Krieger (1649–1725), whose opera songs were in the tradition of the simple German lieder. The subject matter of the Weissenfels operas, however, was not distinctively German; the repertoire shows a strong preponderance of mythological dramas and ballets. A similarly ambiguous picture is presented at many of the lesser courts—German elements struggling against a rising tide of Italian opera, which by the fourth decade of the eighteenth century had won the field everywhere.

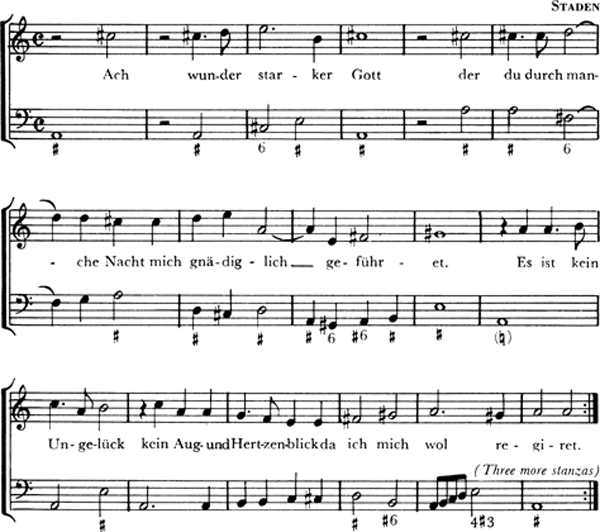

The most likely German forerunner of opera was the school drama, a play in Latin or German, usually of a moral or religious nature, didactic in aim, performed by the students of a school or seminary. Many of these dramas in the sixteenth century included instrumental dances, solo odes, and choral pieces.10 In the early seventeenth century, the musical portions became more extensive. Although the Thirty Years War put an end to the most flourishing era of the school drama, its influence may be seen in the earliest German opera whose music has been preserved: Seelewig, a “spiritual pastorale” by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, set to music by Sigmund Theophil Staden (1607–55), and published at Nuremberg in 1644 in a family periodical.11 As with the first Hamburg opera, nearly thirty-five years later, the subject matter of this singular extant example for Nuremberg is religious. The form is allegorical: Seelewig is the Soul; the villain of the piece is Trugewalt, who attempts to ensnare Seelewig with the help of other characters representing Art, the Senses, and so on, while Wisdom and Conscience act as Seelwig’s defenders. The final triumph of virtue is celebrated by an invisible chorus of angels. This highly moral drama is placed in a fashionable pastoral setting: the sylvan scenes are described in poetry filled with moral symbolism, and Seelewig’s companions are nymphs and shepherds, while Trugewalt is portrayed as a satyr. Each of the three acts is introduced by a sinfonia, and there are a few other short instrumental pieces, together with the composer’s direction that more may be added if necessary in order to avoid pauses during the changing of the scenery. The second and third acts conclude with a choral movement, a feature characteristic of the German pastorale. The solo songs, which constitute most of the music, have short melodies, and nearly all are in strophic form. Perhaps the best of these songs is Seelewig’s outburst of thanksgiving in the closing scene (example 8.1).

EXAMPLE 8.1 Seelewig, Act III, scene vi

Seelewig was not the only effort of Harsdörffer along operatic lines. If in that work he showed himself a follower of the Italian pastorale, in Die Tugendsterne he sought to turn to moral purposes another favorite genre, the ballet with machines.12 Still another play, Von der Welt Eitelkeit, consists of four allegorical scenes, each representing a worldly Vanity, with an epilogue sung by Death.13 No doubt such works are exceptional, in that they were designed primarily for reading rather than performance, but they show what kind of stage spectacles presumably interested the citizens of Nuremberg at this period. A later Nuremberg composer, Johann Löhner (1645–1705), is represented for us by some surviving arias but no complete scores.

With the increase of Italian opera everywhere in the south, the native school found a home not in one of the courts but in the free imperial north German city of Hamburg. Here for sixty years (1678–1738) flourished with varying fortunes a public opera house, the first in Europe outside Italy, where German composers were able for a time to combine contributions from Italian and French sources with their own genius to make an original, truly national form.14

The earliest Hamburg operas show the influence of the school drama. The initial work performed in the new opera house presented the story of Adam and Eve, under the title Der erschaffene, gefallene und wieder aufgerichtete Mensch (1678), with music by Schütz’s pupil Johann Theile (1646–1724).15 Many similar titles appeared in the next few years. Such material was not only traditional but also useful in retaining the good will of the Lutheran church authorities and providing a defense of the opera against frequent attacks on the ground of its worldly and immoral character. Despite sporadic opposition, secular operas soon gained the ascendancy. Composers and poets began to introduce subjects from the Italian and French stages—chiefly translations or adaptations from Venetian librettists (especially Minato), but also occasionally from Corneille (Andromeda und Perseus, 1679), from Quinault (Alceste, 1680), and from Italian comedies. In addition, a few foreign operas were performed in French (Lully’s Acis et Galatée, 1689, and Colasse’s Achille et Polyxène, 1692), or in Italian (Cesti’s La schiava fortunata, 1693,16 and Pallavicino’s Gerusalemme liberata, 1693, among others). Many of Steffani’s works were presented in German translation, and a number of German composers chiefly associated with other cities or courts were also represented in the Hamburg repertoire, notably Schürmann, Strungk, and Krieger. As in Venice, the stage machinery played a conspicuous role.

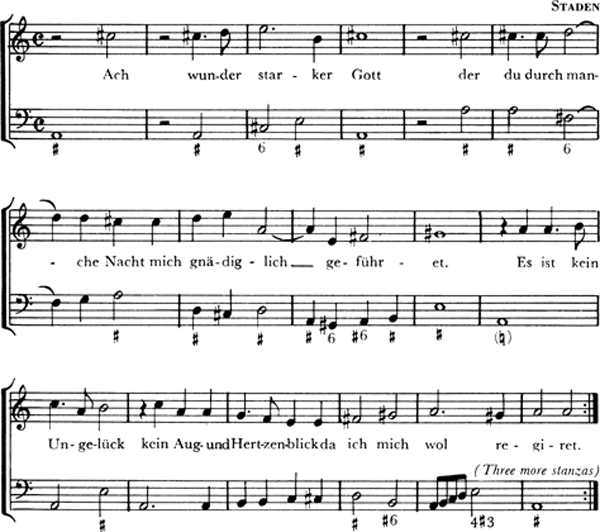

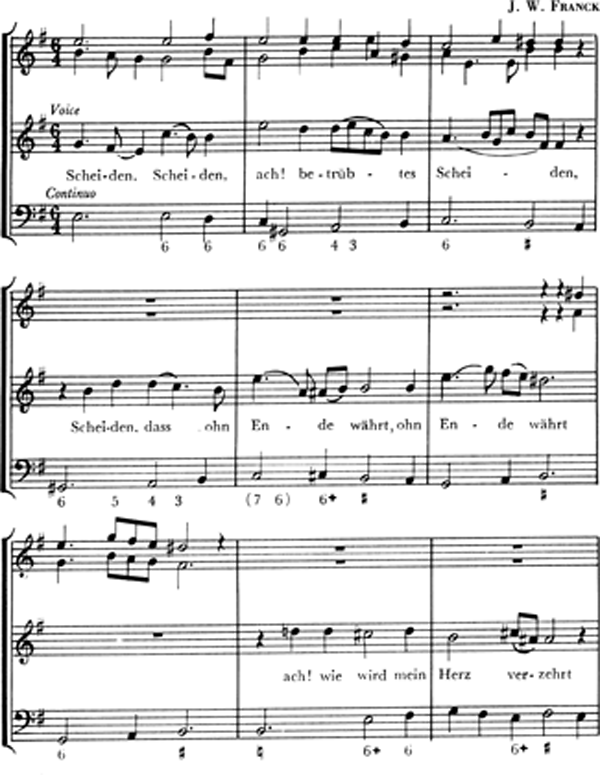

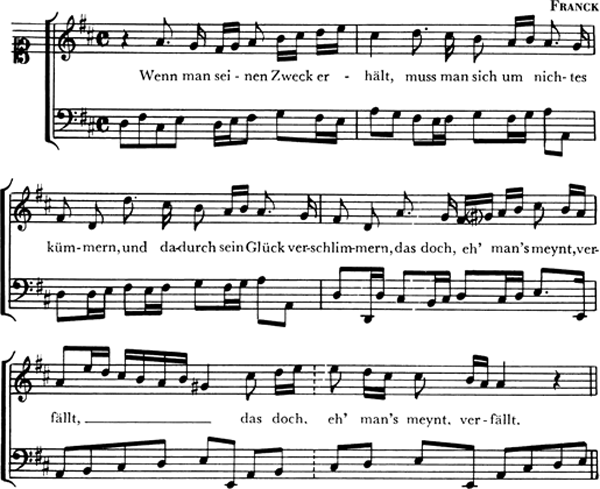

So far as their literary quality is concerned, the Hamburg librettos were on the average neither worse nor better than those of contemporary Italian opera, on which they were modeled. The most active librettists were Christian Heinrich Postel, Friedrich Christian Bressand (also active at Brunswick), Lucas von Bostel, and Barthold Feind, who took the lead in cultivating caricature and parody. No doubt Feind introduced these elements to prevent his librettos from spawning operas that audiences would find “boring and tedious.”17 Among those who composed the music for the Hamburg stage were Johann Wolfgang Franck (1644–c. 1710), Johann Philipp Förtsch (1652–1732), Johann Georg Conradi (d. 1699), and Johann Sigismund Kusser (1660–1727).18

Franck’s earliest operas were composed for Ansbach, but between 1679 and 1686 he composed more than twenty operas for Hamburg.19 His music is serious in tone and shows a fine feeling for long-breathed, expressive lines as well as for melodies in a lighter, more popular vein, as representative examples (8.2 and 8.3) from Cara Mustapha (1686) and Die drey Töchter des Cecrops (1680; revised, 1686) demonstrate.20 He writes arias in a variety of musical forms, including the da capo. He uses a wide range of keys and—exceptional for this time—his scores seem to show evidence of consciously designed tonal architecture. Franck’s recitative is more melodic, slower in tempo, and altogether of more musical significance than that of contemporary Italian opera; its style rather resembles the recitative of German seventeenth-century church composers, half declamation and half arioso, measured and dignified in tone, composed with great care for both the rhythm and the expressive content of the text. Altogether, Franck’s is a full-textured, stiff-rhythmed Baroque music, unmistakably Italian in inspiration but tinged with the serious, heavy formality of Lutheran Germany.

EXAMPLE 8.2 Aria from Cara Mustapha

Although the number of operas written by German composers for Hamburg’s Gänsemarkt theater from the time of its inauguration in 1678 was considerable, many of these works have since disappeared. This is the case with the twelve operas Förtsch composed from 1684 to 1690, and therefore the importance of his contribution to the Hamburg repertoire cannot be fully ascertained.21 Remarkably, the earliest surviving work composed for a Hamburg production dates from as late as 1691: Die schöne und getreue Ariadne, with a libretto by Postel and music by Conradi.22 In Ariadne one can find a mixture of styles—Venetian, German, and French—but it is the French style that is the predominant influence in the arias and instrumental music. When Conradi was at the court in Ansbach in the 1680s, he came to know that style through performances of Lully’s operas there and subsequently incorporated the French style into the nine operas he composed for Hamburg, of which number only Ariadne survives.

EXAMPLE 8.3 Die drey Töchter des Cecrops, Act V, scene iv

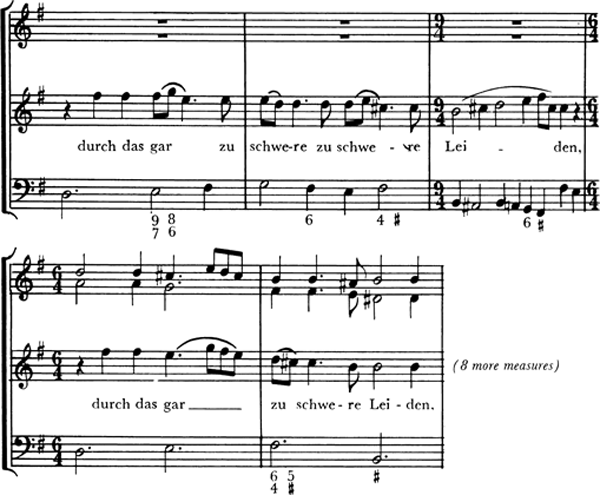

Kusser had also acquired a taste for French music from his studies under Lully during a sojourn of eight years in Paris. Kusser’s operas, which exhibit a more cosmopolitan style, were performed at Brunswick and Stuttgart as well as at Hamburg, where he worked from 1694 to 1696. His Erindo (1694) is a pastorale on the model of Guarini’s Il pastor fido—a choice of libretto attributable perhaps to the composer’s French background, since pastorales were uncommon in Italian opera at this period. Kusser’s music, as far as can be judged from the extant materials of Erindo, is distinguished by attractive cantabile melodies, clear formal and tonal schemes, skillful use of concertizing instruments, and numerous little songs in French dance rhythms, such as the passepied (example 8.4), minuet, and gavotte.23 His importance for the history of German opera is apparently due less to his standing as a composer than to his influence as a conductor and impresario. By making the German public better acquainted with French and Italian music, he was instrumental in preparing the way for the international style of Mattheson, Keiser, and Handel, the leading composers of opera at Hamburg during the early part of the eighteenth century.

EXAMPLE 8.4 Duet from Erindo, Act III

1. The conditions of early German opera are reflected in the fact that the majority of studies in this field are in the form of local or regional histories, embodying chronicles and statistics. References to this extensive literature will be found in the three general surveys of the period: Kretzschmar, “Das erste Jahrhundert der deutschen Oper,” in his Geschichte der Oper, 133–57; Moser, Geschichte der deutschen Musik, 2:bk. 2, chap. 3; and Schiedermair, Die deutsche Oper, part 1. See also Bolte, Die Singspiele der englischen Komödianten; Haas, “Die Oper in Deutschland bis 1750”; G. F. Schmidt, “Zur Geschichte, Dramaturgie und Statistik”; Brockpähler, Handbuch zur Geschichte der Barockoper in Deutschland. A bibliography of local and regional histories of German music will be found in Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, s.v. “Deutschland” and The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Contemporary biographical profiles of many composers are to be found in Mattheson, Grundlage einer Ehrenpforte (1740).

2. A proverb at the Brunswick court in the latter part of the seventeenth century ran: “Wer nicht französisch kann, Der kommt bei Hof nicht an.” Hartmann, Sechs Bücher, 85.

3. Cf.[Hunold:] “Eine Opera oder ein Sing-Spiel ist gewiss das galanteste Stück der Poesie, so man heut zutage aestimieren pfleget,” in his Die allerneueste Art (1707), 394.

4. See G. F. Schmidt, Die frühdeutsche Oper, 2:45–54.

5. Among them were four other operatic works by Schütz for which only the librettos survive. For a listing of Baroque opera in Germany, see Brockpähler, Handbuch.

6. Engländer, “Zur Frage der Dafne.”

7. G. F. Schmidt, Die frühdeutsche Oper.

8. Spitta, Johann Sebastian Bach, 2:854.

9. The most obviously dramatic work of Bach is Phoebus und Pan (composed for the Leipzig Collegium Musicum in 1731), which one contemporary called a “Gesprächspiel” (Spitta, Bach. 2:740). Several of the so-called secular cantatas actually bear the designation “Drama” or “Drama per Musica,” and others (e.g., the “Coffee Cantata”) are semi-dramatic—not to mention the Passions and oratorios, in which the influence of dramatic forms is clearly evident.

10. See Flemming, Geschichte des Jesuitentheaters; Liliencron, “Die Chorgesänge des lateinischen-deutschen Schuldramas”; Schünemann, Geschichte der deutschen Schulmusik, 67ff., 137; Culley, Jesuits and Music.

11. Cf. Keller, Die Oper Seelewig; Harris, Handel and the Pastoral Tradition, chap. 3. The music appears in Harsdörffer’s Frauenzimmer Gesprächspiele, 4:31–165, 489–622. For more on this periodical, see Narciss, Studien zu den Frauenzimmergesprächspielen, 93–96.

12. The title may be translated as “The Stars of Virtue”; the music was by Staden. See Frauenzimmer Gesprächspiele, 5:280–310, and Haar, “Astral Music in Seventeenth-Century Nuremberg.”

13. Frauenzimnmer Gesprächspiele, 3:170–242. A nearly complete reprint, with the music, appears in Schmitz, “Zur musikgeschichtlichen Bedeutung,” 264–75.

14. See Wolff, Die Barockoper in Hamburg (the second volume consists entirely of musical examples); Schulze, Die Quellen der Hamburger Oper (1678–1738); Marx,” Geschichte der Hamburger Barock Oper”; Marx and Schröder, Die Hamburger Gänsemarkt-Oper; Zelm, “Die Sänger der Hamburger Gänsemarkt-Oper”; Kleefeld, “Das Orchester der Hamburger Oper”; Braun, Vom Remter zum Gänsemarkt.

15. Zelle, Johann Theile und Nikolaus Adam Strungk.

16. Prior to this production, La schiava fortunata had been adapted from Cesti’s La Semirami (Vienna, 1667) for Modena (1674) and Venice (1674/76), the latter with additional music by M. A. Ziani.

17. These words appear in Feind’s writings on opera, which are set forth in his Deutsche Gedichte … Gedancken von der Opern (1708), excerpts of which are reprinted (in English) in Bianconi, Music in the Seventeenth Century, 311–26. Also included in these same excerpts are Feind’s remarks that “half the world” has accepted operas as being neither “edifying” nor “reprehensible”—remarks meant to counter Protestant opposition to operatic productions in Hamburg.

18. Kusser’s name is sometimes spelled Cousser or Cusser. See Scholz, Johann Sigismund Kusse r, and Samuel, “John Sigismond Kusser in London and Dublin.”

19. See Squire, “J. W. Franck in England”; G. F. Schmidt, “Johann Wolfgang Francks Singspiel Die drey Töchter des Cecrops”; Günther Schmidt, Die Musik am Hofe der Markgrafen von Brandenburg-Ansbach; Klages, “Johann Wolfgang Franck”; Buelow, “Hamburg Opera during Buxtehude’s Lifetime: The Works of Johann Wolfgang Franck.”

20. Of the operas Franck composed for Hamburg, only one survives in a complete state, Die drei Töchter des Cecrops. This score, however, does not represent the Hamburg production, but rather an expanded version related to what is believed to have been a 1686 revival in Ansbach. See Braun, “Die drey Töchter des Cecrops: Zur Datierung und Lokalisierung von Johann Wolfgang Francks Oper.”

21. See Wiedemann, Leben und Wirken des Johann Philipp Förtsch, 1652–1732.

22. See Buelow, “Die schöne und getreue Ariadne (Hamburg, 1691): A Lost Opera by J. G. Conradi Re-discovered.”

23. Notably lacking from the extant items are many of the choral numbers. For a discussion of Erindo, see Harris, Handel and the Pastoral Tradition, 75–80.