The Operas of Mozart and

His Viennese Contemporaries

MOST OPERA COMPOSERS have been specialists; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91) was one of the few whose greatness was manifested equally in opera and in other branches of composition. His genius and training led him to conceive of opera as essentially a musical affair, like a symphony, rather than as a drama in which music was merely one means of dramatic expression. In this conception he was at one with the Italian composers of the day, and his work may be regarded in a sense as the ideal toward which the whole eighteenth-century Italian opera had been striving. He overtopped his predecessors not by a changed approach to opera but by the superior beauty, originality, and significance of his musical ideas, by his greater mastery of counterpoint, by his higher constructive powers, and by his ability to write music that not only perfectly portrayed a dramatic situation but also could develop freely in a musical sense, without appearing to be in the least hampered by the presence of a text. The variety of musical forms in Mozart’s operas, which can best be appreciated by an analysis of the scores, is paralleled by the skill with which these forms are adapted to the dramatic aims. In this rare combination of dramatic truth and musical beauty, there can be no doubt that the music is the important thing. Without it, none of the operas, except possibly Le nozze di Figaro, would be intelligible; with it, even Die Zauberflöte makes sense. So completely does the music absorb the drama, and so perfect is the music itself, that Mozart today not only holds the stage but offers the phenomenon of one composer whose operas are universally enjoyed by opera-goers and music lovers alike.1

It is no disparagement of Mozart to remark that, like many another great man, he was born at the right time. Everywhere there were producers ready to stage new operas and audiences ready to listen to them; the classical orchestra and orchestral style were well beyond the experimental stage; the art of singing, though beginning to decline, was still at a high level of virtuosity; the opera itself had the advantage of an established form within which recent developments—the innovations of Gluck, the vitality of opera buffa, and the growing interest in the German Singspiel—offered stimulating possibilities to a composer. Mozart’s operas were, on the whole, successful; if they did not obtain for him all the reward or recognition that their merits deserved, and for which he hoped, the fault lay not in the conditions of the time so much as in the fact that Mozart personally was always unfortunate in his adjustments to the patronage system and that the Viennese public, which might have sustained him, was not yet capable of appreciating those qualities that set him above Dittersdorf and other popular Singspiel composers. In other words, Mozart was slightly in advance of his time, but he was no more a conscious revolutionist in opera than was Handel. His twenty or more dramatic works (at least ten of them written before the age of twenty-five) include school dramas, serenatas, and Italian serious operas, but the greater part of his output is in the two fields most cultivated in the later eighteenth century, the Italian opera buffa and the German Singspiel.

The Italian Operas

The predominance of an Italian background in Mozart’s music is natural, since Italian music was the international standard of his time. The strong early influence of Johann Christian Bach (London, 1764–65), the three Italian journeys of his boyhood, and a course of contrapuntal studies with (Padre) Giovanni Battista Martini in 1770 all strengthened this tendency. Among Mozart’s childhood works was an Italian opera buffa, La finta semplice, composed for Vienna in 1768 but not performed until the following year at Salzburg. At the age of fourteen, he composed his first opera seria, Mitridate, re di Ponto, which was performed at Milan in December 1770. Two years later, another work of the same type, Lucio Silla, was also produced at Milan. Both are on librettos of the conventional type established by Metastasio and are more remarkable as examples of Mozart’s extraordinary precocity than for anything else. His aim—and the aim of his father, who still closely supervised his compositions—was to produce successful operas according to the current Italian standard. We marvel at the degree to which Mozart had assimilated the operatic manner of his time, but the whole effect is similar to that produced by any performance of a child prodigy: brilliant but inappropriate coloratura passages abound in these early scores, and there is little individuality of melody and nothing of the later variety of forms or, except in a few places, true characterization of the text. One aria in Mitridate, Aspasia’s “Nel sen mi palpitar” (no. 4), foreshadows the Mozartean pathetic style; in Lucio Silla, the ombra scene with chorus (Act I, scenes 7–8) is an imaginative and even powerful treatment of the situation, while Cecilio’s aria “Quest’ improvviso tremito” (no. 9), with the preceding accompanied recitative, is an unusually dramatic solo in the grand style. The success of these early works was not great, and though his interest in the form continued, it was nearly ten years before Mozart had the opportunity to compose another opera seria.

La finta giardiniera, produced at Munich in 1775, was an Italian opera buffa with a libretto that unhappily combined the new sentimental style of Goldoni’s Cecchina, ossia La buona figliuola with a complicated and cumbersome array of secondary characters, disguises, mistaken identities, and farcical episodes inherited from the older Italian comedy.2 The music is only too faithful to the text, with the consequence that it not only lacks dramatic continuity but also presents the same characters at different moments in contradictory aspects. Tragedy and comedy rub shoulders, but there is no sign of the synthesis of the two, which is so characteristic of Mozart’s later dramatic works. Thus the heroine Sandrina is presented in Act I (no. 4) as a superficial young girl of the usual comic-opera type but in Act II (nos. 21, 22) as a tragic figure appropriate to opera seria. Aside from such inconsistencies that were so common in this period, the score of La finta giardiniera is extraordinarily attractive. The musical material is individual and is treated with imagination and humor. The serious portions mark an important advance in Mozart’s handling of this type of expression, however out of place they are dramatically. Another notable feature is the finale of Act I, where the development of the action is combined with character differentiation and musical continuity, giving a foretaste of the finales of Figaro and Don Giovanni.3

The remaining early Italian works may be briefly noted here. Ascanio in Alba (Milan, 1771), a serenata in two parts, is notable for its choruses, dances, and accompanied recitatives.4 The serenata Il sogno di Scipione (Salzburg, 1772) and the festival opera Il re pastore (Salzburg, 1775) offer nothing of particular interest or significance in Mozart’s development. They were occasional pieces composed as part of his duties in the service of the archiepiscopal court and (like many of their kind) were adequate but uninspired—with the exception of one aria with a solo violin obbligato, “L’amerò, sarò costante” in Act II of Il re pastore, which is a lovely example of Mozart’s lyrical powers.

The influence of Italian opera in Mozart’s dramatic career was balanced and modified by his interest in symphonic music. Stemming from Italy and originally based to a large extent on the musical idiom and forms of Italian operas, the pre-classical German symphony was at a flourishing stage when Mozart visited one of its chief centers, Mannheim, in 1777–78. Before this date he had already composed many symphonies, two of which especially (K. 183 and 201) showed a sure grasp of the form, but the works of Johann Stamitz and the Mannheim school were among the models that most influenced him in his mature years. His close association with Christian Cannabich (1731–98), who had succeeded Stamitz as conductor of the famous Mannheim orchestra at the time of Mozart’s visit, led to a deeper appreciation of the symphonic style and of the possibilities of orchestral manipulation in general. This is not the place to speak of Mozart as a symphonist, except to point out that his lifelong interest in and mastery of the larger instrumental forms are reflected on every page of his operas—in the way in which voices and instruments are adjusted to one another, in the texture and treatment of the orchestral parts (particularly the independence of the woodwinds), in the broadly symphonic overtures, and in the unerring sense of musical continuity extending over long and complex sections of the score.

At Mannheim, Mozart also came into contact with German opera—not the Singspiel but the new German opera, raising its head again after a forty-year sleep. In 1773 Wieland’s five-act Alceste, with music by Anton Schweitzer, was performed at Mannheim with such success that in January 1777 a second German opera, this time on a subject from German history, was presented: Günther von Schwarzburg, composed by Ignaz Holzbauer (1711–83). Mozart wrote enthusiastically of Holzbauer’s music, which is indeed fiery and spirited, though both it and the libretto show all too plainly the outlines of Italian opera seria. Neither Schweitzer nor Holzbauer was able to bring about a permanent awakening in Germany; the time was not ripe, and their works, although performed at Mannheim and in several other cities, remained only an episode, albeit an important one, in the history of national opera.5 Yet the ideal persisted; Mozart’s Zauberflöte, which has strains reminiscent of Günther, was to be the first effective step toward its realization.

From Mannheim, Mozart journeyed to Paris, arriving in March 1778 in the midst of the Gluck-Piccinni controversy. An unknown young foreign musician, he attracted little attention—a disappointing contrast to his reception fifteen years before as a child prodigy. His temperament, converging with the anxious advice of his father, kept him aloof from the current quarrel. Moreover, the whole tone of musical life and society in Paris was discouraging to him, with its endless theorizing and debating about matters, which he himself either understood quite simply as a musician or else felt to be of no importance. He had no sympathy for French opera and could not abide French singing; the opéra comique apparently did not interest him, and he does not seem to have made the acquaintance of Grétry. Plans for a French opera came to nothing, and the only theater music of this period was part of a ballet, Les Petits Riens (K. Suppl. 10), arranged by Noverre and performed in connection with one of Piccinni’s operas. Mozart’s joy over the success of his “Paris” Symphony (K. 297) was turned to sadness by the death of his mother; he left Paris in September and returned to Salzburg no richer in either money or prospects than when he had left. Yet the Paris visit was not without importance, for it helped to make Mozart for the first time more fully conscious of his own artistic aims and of his position as a composer in relation to the ideals of Gluck and the French school.6

In 1780 came a welcome commission to provide an opera seria for Munich. The result was Idomeneo, re di Creta (1781), the first opera that shows Mozart in the fullness of his powers.7 The libretto, on a subject first used by the French composer Campra in 1712, was written by the Abbé G.B. Varesco of Salzburg; it is of the old-fashioned Metatasian type, on a classical subject with amorous intrigues, but including some large choral scenes in the newer style of Marco Coltellini and Carlo Frugoni. The music also is old-fashioned in some external details: there is the conventional framework of recitatives alternating with arias; one of the principals is a male soprano; and there are many brilliant coloratura songs with improvised cadenzas, such as Idomeneo’s comparison aria “Fuor del mar” in Act II and Electra’s “Tutte nel cor vi sento” in Act I, which is especially notable for the striking effect made by the return of the first theme in C minor after the original statement in D minor.8 Ensembles are few: two duets, one trio, and one quartet, this last considered by Mozart to be one of the finest numbers in the whole opera. In accordance with late eighteenth-century practice, there is relatively little secco recitative but a large number of accompanied recitatives. One of the best of these is the highly dramatic recognition scene between Idomeneo and his son Idamante in Act I (“Spietatissimi Dei”), a masterpiece of psychological perception and effective harmonic treatment.9

Like the operas of Jommelli, Traetta, and Gluck, Idomeneo is filled with large scene-complexes built around recitative, with free musical and dramatic handling, often combined with spectacular effects—for example, the oracle scene in Act III. Many of these scenes introduce ballets, marches, and choruses.10 The extent and importance of the choral portions are reminiscent of Rameau and Gluck: the last scene of Act I has a march and chorus (ciacona) that is similar to the choral scenes of older French operas, as is also the well-known chorus “Placido è il mar, andiamo” in Act II. More like ancient Greek usage is the scene in Act III between Idomeneo and the chorus, in which the latter comments, warns, and expostulates. The most dramatic choral scene is that at the end of the second act, where the repeated cries of the chorus, “Il reo qual è?” (Who is the guilty one?), the feeling of terror enforced by the strange, swiftly changing tonalities of the music, the tumult of the storm in the orchestra, Idomeneo’s anguished confession, and the final dispersal and flight of the people all form a great and powerful finale equal in force to anything of Gluck’s and surpassing Gluck in fertility of musical invention.

Mozart’s understanding of the style of opera seria is seen here in his treatment of the most traditional of operatic forms, the aria, of which we may single out two examples for special mention. Ilia’s “Se il padre perdei” in Act II is a splendid example of Mozart’s sensitiveness to details of the text, of his ability to unite many different aspects of feeling in one basic mood, and of his imaginative use of orchestral accompaniment for subtle psychological touches. Ilia’s third aria, “Zeffiretti lusinghieri,” in Act III, brings a commonplace conceit of eighteenth-century opera into a setting that simply transfigures the faded sentiments of the poem by the freshness of the music.

Nowhere in his operas did Mozart lavish more care on the orchestral writing than in Idomeneo. This is seen especially in the independence of the woodwinds and their frequent employment for the most subtle touches of color and expression.11 The overture at once sets the tone of lofty seriousness that prevails throughout the opera. At the end, the music dies away with a tonic pedal point, over which we hear in the woodwinds a series of repetitions of a characteristic descending phrase that recurs several times during the opera, alternating with rising scale-passages; the final chord of D major, owing to the plagal harmonies, has the effect of a dominant in G, thus leading into the G minor accompanied recitative with which the first act opens.

It is perfectly clear that in writing Idomeneo Mozart had before his mind not only the most recent developments in the Italian opera seria but likewise the French operas of Gluck, with which he was well acquainted. In many respects, Idomeneo is the finest opera seria of the late eighteenth century; it shows that Mozart had fully appreciated the advances made by Jommelli, Traetta, and Sarti and thus marks an important stage in his own development over his youthful dismissal of Jommelli’s Armide as “too serious and old-fashioned for the theater.”12 Mozart surpassed Jommelli in spontaneity, variety, and richness of invention but even more in his grasp of the emotional content of the text and in his incomparable power of musically characterizing persons and situations. To the mastery of traditional outward forms he added the quality of psychological insight and a genius for expressing this insight in musical terms. Observing his treatment of the opera seria, we are made aware that a miracle is taking place: the two-dimensional figures of the old dramma per musica suddenly take on a new dimension, and we see them in depth and perspective. Yet all this did not amount to a fundamental reform. Idomeneo was not the starting point of a new evolution in opera seria but rather one of the last great examples of a form that was already on the decline.

The presence of choral scenes in Idomeneo does not indicate acceptance of Gluck’s reform theories. Mozart simply adapted for his own purposes certain practices by which the leading Italian composers of the time were seeking to rejuvenate the opera seria. To regard him as in any sense a disciple of Gluck is to misunderstand both men. As a matter of fact, the contrast between two contemporary opera composers could hardly be greater. On the one hand, Gluck, at least as far as Orfeo and later works are concerned, was an artist to whom the conscious perception of aims and rational choice of means were necessary preliminaries to musical creation; every detail of his scores was the result of a previously thought-out plan, and he was always ready to justify his procedures by reference to his intentions. Mozart, on the other hand, was no philosopher; thought and realization were to him indivisible parts of the same creative process. His music was no less logical than Gluck’s, but it was the logic of music, not something capable of being detached and discussed in relation to extra-musical conceptions. For him, “in an opera, poetry must be altogether the obedient daughter of the music.”13 With Gluck the idea of the drama as a whole came first, and the music was written as part of the means through which the idea was realized. With Mozart the idea took shape immediately and completely as music, the mental steps involved in the process being so smooth and so nearly instantaneous that he has often been called an “instinctive” composer, though that is incorrect—unless we choose to denote by the word instinct that sureness, clarity, and speed of reasoning that is characteristic of genius.

In addition to this difference of temperament, there was a fundamental difference between Gluck’s and Mozart’s conceptions of drama. Gluck’s characters are generalized and typical rather than individual. They have a certain classic, superhuman stature, and as they are at the beginning of an opera, so they remain to the end. But Mozart’s characters are human persons, each uniquely complex and depicted variously in changing moods rather than statically as a fixed bearer of certain qualities. It is for this reason that Mozart’s operas seem to us modern while Gluck’s seem old-fashioned. Gluck’s dramatic psychology is that of the eighteenth century; Mozart’s is that of our own time. The symbols of the contrast are the Gluck chorus, in which the individual is submerged in the typical choral grouping of unnamed personages, and the Mozart ensemble, in which the individual is all the more sharply defined by means of interaction with other individuals.

Finally, Gluck’s music, quite apart from any technical inferiority to Mozart’s, is intentionally austere. Its appeal is not to the senses and emotions primarily, but to the entire “rational” person, as conceived in the eighteenth century. Much of the music therefore (though we must make important exceptions to this statement, especially in Orfeo) lacks those qualities of ease and spontaneity that are never absent from the music Mozart composed, even in his least inspired moments. To appreciate Gluck, one needs to know something about the eighteenth century, but no comparable background is required in the case of Mozart.

With the exception of two unfinished pieces of 1783, Mozart’s next Italian opera was Le nozze di Figaro, first performed at Vienna on May 1, 1786. During the five years between Idomeneo and Figaro, Mozart had become acquainted with the music of Bach and Handel, and he had written Die Entführung aus dem Serail, the “Haffner” Symphony, the six “Haydn” quartets, and many of the great piano concertos. Although he was now a mature artist, at the height of his powers, he still had to contend with competition from his rivals in the imperial city, not the least of them being Antonio Salieri and the popular Spanish-Italian composer Vicente Martín y Soler, whose works dominated the musical life there in the 1780s. Nor was this rivalry limited to productions at the Burgtheater. In 1786, for example, Mozart’s one-act opera Der Schauspieldirektor was presented at the Schönbrunn Palace Orangery on the same program with Salieri’s one-act comedy Prima la musica e poi le parole, a satire on how a composer fulfills an opera commission from his patron within the unreasonable time limit of four days.

Salieri came to Vienna in 1766; four years later his first opera, Le donne letterate, was performed in the Burgtheater. From that modest beginning, Salieri rose to prominent positions at the imperial court, first as composer and conductor of Italian opera in 1774 and then as Hofkapellmeister in 1788. During his tenure in Vienna, he created more than forty operatic works.14 Many of those staged in Vienna after 1784 were written in collaboration with the librettist Lorenzo da Ponte (1749–1838), whom Joseph II appointed poet for the Burgtheater in 1783.15 They include Il riccio d’un giorno (1784), set to Da Ponte’s first libretto; Axur, re d’Ormus (1788), an Italian adaptation by Da Ponte of the Beaumarchais libretto Tarare that Salieri had previously set for Paris in 1784; La cifra (1789); and Falstaff (1799), an exceptionally well-structured two-act comedy, with a libretto by C. P. Defrancaschi based upon Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor. Salieri infused Falstaff with a feature of the commedia dell’arte performances, overlaying the singers’ roles with a certain amount of physical activity (running, leaping) so that their actions would communicate to the audience a sense of frivolity. Particularly distinguished are his comic ensembles in this opera, such as the extensive buffo scene at the end of Act I, where Falstaff is smuggled out of the house in a laundry basket.

Da Ponte created the libretto for Salieri’s Axur at the same that he was writing the librettos for Martín y Soler’s L’arbore di Diana and Mozart’s Don Giovanni. In his transformation of Beaumarchais’ Tarare into a dramma tragicomico, Da Ponte tended to replace simple recitative passages with ensembles (such as the duets in the opening scenes of the first and third acts) and to eliminate politically charged elements (such as Calpigi’s aria at the end of the fourth act). At the same time, he retained a number of the salient features of the French libretto, not the least of them being the extensive use of the chorus—even an offstage chorus that briefly interrupts one of the love duets in Act I. Aspects of the Vienna score that engendered particular praise from contemporaries included the music Salieri composed for the temple scenes in Act II. Axur not only held the stage in Vienna until 1805 but also received successful performances throughout the German lands and in Paris, Lisbon, Moscow, and Warsaw.

When Da Ponte adapted Beaumarchais’ Le Mariage de Figaro for Mozart, he provided the composer with a libretto that combined comedy with excellent possibilities for character delineation. Beaumarchais’ play was completed in 1778, but owing to difficulties with censorship at Paris, performances were delayed for several years. When the play finally came to the stage in 1784, it achieved an immediate success, in part because the author had seasoned his comedy with the fashionable revolutionary doctrines of the time. The story is a sequel to Beaumarchais’ Le Barbier de Seville, which had been so popular in Paisiello’s setting four years previously. Needless to say, the subversive aspects of the plot were not unduly emphasized by Da Ponte or Mozart in an opera intended for Vienna, where Beaumarchais’ play was still forbidden. The first performance of Figaro was a great success;16 it was therefore all the more disappointing to Mozart that his opera was soon displaced in the affections of the public by newer works, among them Doktor und Apotheker by Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf and Una cosa rara and L’arbore di Diana (1787) by Martín y Soler.17

Una cosa rara had its premiere at Vienna’s Burgtheater in November 1786. Da Ponte provided the libretto, fashioned from a Spanish play by Luis Vélez di Guevara. The opera is set in the Spanish countryside, the pastoral nature of which is picked up by the music (with many numbers in 6/8 meter). Martín y Soler underscored the foreign flavor of the production by having Titta (the country bumpkin) sing a mixture of Spanish and Italian lyrics during a confrontation with his friend Ghita, by inserting a seguidilla in the finale of Act II, and by presenting the actors in traditional Spanish costumes. Count Zinzendorf, in his diary entry for November 17, 1786, takes note of the costumes, remarking that they subsequently sparked a fashion craze among the elite of Vienna.18

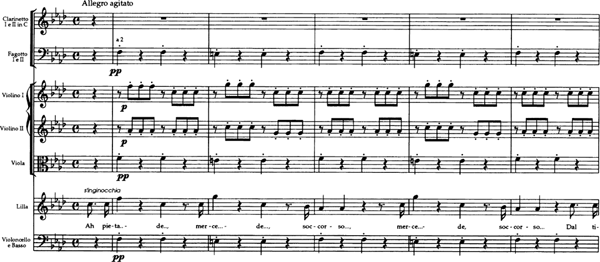

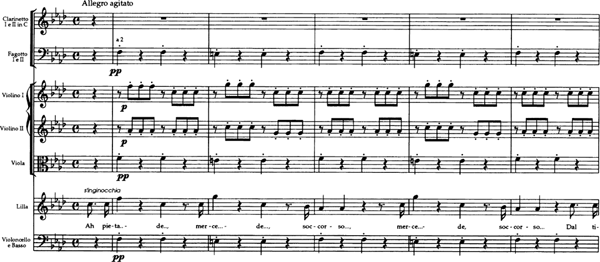

Of particular interest is the style of the music found in the much-discussed “Ah, pietade, mercede,” sung by the shepherdess Lilla as she makes her initial entrance in Una cosa rara. Here Lilla’s distress at the unwanted advances made by persons above her station in life, namely the Prince and his Courtier, is rendered musically by a “breathless” cavatina. The pauses between words and even between syllables of words in Lilla’s melodic line mirror her pathetic situation, namely that she is at a loss for words to express her rejection of these suitors. The repeated chords in the accompaniment sustain the intensity of her grief (example 16.1)19

Mozart was influenced by the sentimental style of this cavatina, as shown by his parody of it in Don Alfonso’s cavatina “Vorrei dir” in Così fan tutte. Nor is this the only instance in which Mozart had occasion to be involved with Martín y Soler’s operas. In the second act finale of Don Giovanni, he quotes a melody from Una cosa rara, and on the occasion of a revival of Martín’s Il burbero di buon cuore, Mozart composed substitute numbers (an accompanied recitative and an aria, “Vado, ma dove?”) to accommodate Luisa Villeneuve, a singer whose talent far exceeded that for whom Martín’s music was originally intended.20

What Mozart did not imitate, however, was the social disparity that pervades Una cosa rara. Martín y Soler’s characters are molded according to the conventions of eighteenth-century Viennese opera; Mozart’s characters break with tradition. No characters in any eighteenth-century opera give more strongly the impression of being real persons than do Figaro and Susanna, the Count and Countess, Cherubino, and even the lesser figures of this score. It is therefore important to point out that this vividness of characterization is due not to Da Ponte or Beaumarchais but to Mozart, whose imagination conceived his characters not as stock figures in opera buffa going through a set of conventional antics travestied from the superficial aspects of current daily life, nor yet as social types in an eighteenth-century political pamphlet, but as human beings, each feeling, speaking, and behaving under certain vital circumstances very much as any other human being of like disposition would under similar conditions, whether in the eighteenth century or the twentieth. Just how music succeeds in making us aware of this timeless quality is not easy to describe, but no one who has read the libretto and then heard the opera will deny that it does so. It is not merely that the words are sung, or that through his control of tempo, pitch, and accent the composer can suggest the inflections of speech necessary to a given character at a given moment. The secret is rather in the nature of the music itself, in the form created by the extension of a melodic line in time, and in the simultaneous harmonic combinations, rhythms, and colors of the supporting instruments—all of which somehow, given a composer like Mozart, convey to us just those things, inexpressible in words yet infinitely important, which make the difference between a lifeless figure and a living being. Consider, for example, the Countess’s “Porgi amor” or Cherubino’s “Non so più” or “Voi che sapete”: note how little the words alone tell us about the person, and how much the music.21 Indeed, it seems that with Cherubino (significant name!) Mozart has achieved in music what Guillaume de Lorris is said to have achieved in poetry, “that boy-like blending …of innocence and sensuousness which could make us believe for a moment that paradise had never been lost.”22

EXAMPLE 16.1 Una cosa rara (no. 3), “Ah pietade, mercede”

Una cosa rara—Martín y Soler. © G. Henle Verlag, Munich. All rights reserved. Used by kind permission of G. Henle Verlag.

One of the most remarkable things about the character delineation in Figaro is that more of it is done in ensembles than in solo arias. Nearly half the numbers in the score are ensembles, a higher proportion than in the usual Italian opera buffa. The technique of differentiating the persons is extremely subtle, depending on details of rhythm, harmony, accompaniment, and the register or even the tone of the voice, rather than on obviously contrasting melodic lines. Moreover, it all takes place without causing the slightest impediment to the music, which continues to develop in its natural way while carrying on the drama.

The highest examples of Mozart’s skill are to be found in the ensemble finales, in which no other composer before or since has equaled him. This characteristic feature of the opera buffa had attained by Mozart’s time such a high degree of development that Da Ponte could describe it quite correctly as “a sort of little comedy in itself.”23 His ensemble finale represented a section in which all the lines of the action were brought together and driven more and more swiftly to a climax or to the final solution of the plot, involving the appearance on the stage of all the characters, singly and in various combinations, but in increasing numbers and excitement as the end of the act approached. Mozart’s music appropriately follows the general pattern indicated, but it differs from that of the typical Italian opera buffa in two important particulars. Whereas the Italian composers as a rule were concerned only with suggesting bustle and activity and exploiting in every way the often crude farcical elements of the finale, Mozart never loses sight of the individuality of his persons; humor is there in abundance, but it is a finer, more penetrating humor than that of the Italians, a humor of character more than of situations, with that intermingling of seriousness that is the mark of all great comedy. Then too, Mozart’s music in these finales is not merely a succession of pieces in appropriate tempos but is truly symphonic—that is, a Mozart finale is a composition for voices and orchestra in several movements, with variety of texture within each movement, with the musical material developed by essentially the same technique as in a symphony, with a definite relation between principal and subordinate elements, and with continuity and unity arising from an overall plan of tempo successions and key relationships.

The total plan of the finale as a whole in Mozart is an interesting study. In the first finale of Figaro, the principal keys are

In the last finale, the scheme is

The last finale of Così fan tutte is more complicated both dramatically and tonally; it begins and ends in C, with the tonality strongly enforced by the dominant-tonic relation of the last two movements, but dwells on the minor mediant (E-flat) and related keys, with an excursion to E, A, and D in the middle. The first finale of Don Giovanni is tonally in rondo form, thus: dominant–tonic–dominant–tonic. The second finale is similar: tonic (D)–minor mediants–tonic (minor → major)–subdominant–tonic. The first finale of Die Zauberflöte has the key successions C, G, C, F, C, but with many connecting recitative passages and passing modulations; the second finale (E-flat) is remarkable for having no movement in the dominant, the emphasis instead being on the mediant keys of C and G. It may be noted incidentally that in every opera of Mozart from Mitridate on (with the exception of Il re pastore and Die Entführung), the last finale is in the same key as the overture.

The unity within each single movement of a finale comes from its key scheme and from the use of a few simple rhythmic motifs throughout, generally in the orchestra. Forms within these movements are infinitely varied, but each is usually a complete unit; only exceptionally (for example, in the first finale of Figaro) is a particular theme or motif carried over from one movement to another. Each finale is a unique form, resulting from the translation of a dramatic action into symphonically conceived music by a master of that style. The finales are, consequently, invaluable sources for study of the principles—as distinct from the patterns—of symphonic form in the classical period.24

Although Figaro did not have a long run in Vienna, it met with an enthusiastic reception at Prague the following winter, and this resulted in Mozart receiving a commission for a new opera for that city, performed there on October 29, 1787. Da Ponte furnished him with the libretto, Il dissoluto punito, ossia: Il Don Giovanni, a dramma giocoso in two acts.25 The ancient Don Juan legends have been used by playwrights and poets since the early seventeenth century—by Tirso de Molina, Molière, Shadwell, Goldoni, Byron, Lenau (whose poem furnished inspiration to Richard Strauss), and Shaw, among others. Da Ponte appears to have taken his version largely from the libretto for a one-act comic opera, Il convitato di pietra (The Stone Guest) by Giovanni Bertati, which had its first performance at Venice early in 1787, with music by Giuseppe Gazzaniga (1743–1818).26 This was the most recent of some half-dozen musical settings of the story in the eighteenth century before Mozart’s.27

The overture to Don Giovanni paints a vivid picture of the two contrasting moods that will pervade the opera: the slow introduction anticipates the serious scenes while the allegro foretells of the humorous escapades of the title character and his servant Leporello. Mozart’s use of modulation to heighten a dramatically significant moment in this opera is tellingly revealed, for example, in the cemetery scene in which the stone statue nods affirmatively to Don Giovanni’s invitation to join him for dinner. To accompany the statue’s “reply,” the basses in the orchestra momentarily descend to a C natural, the flatted sub-mediant of E major (the key of this scene), producing a startling effect on the audience.

It may seem strange that an action whose catastrophe shows divine vengeance overtaking a libertine and blasphemer should have been treated as a comedy. The reason lies not only in the obvious comic possibilities of the great lover’s adventures but also in the grotesque and fanciful aspects of the statue scenes and the final spectacular punishment of the hero. The legend has a dramatic weakness similar to that of Orpheus in that it is impossible to find a satisfactory ending: moral considerations require that the Don be punished, but unfortunately the spectators either feel so sternly about the matter that the customary lighthearted merrymaking of a closing buffo scene would be improper or else sympathize too strongly with the hero to rejoice at his fate. Da Ponte and Mozart compromised by using a device common in the opéra comique: a “closing moral,” sung by the entire surviving cast, to the effect that the death that overtakes the wicked is a fit end to their misdeeds.28 This was the ending created for the production of Don Giovanni in Prague, but when the opera was staged in Vienna a year later, the libretto published for that production did not include the final scene in which the characters have time to offer their comments upon the fate of the principal character. Instead, the libretto draws to an abrupt close with the surviving characters coming on stage and gasping in horror at the spectacular demise of Don Giovanni, their concerted “Ah!” uttered as the curtain falls on the scene. That Mozart momentarily concurred with this version of Da Ponte’s libretto is supported by his addition of a full vocal chord in the autographed score on which the cast was to sing their “Ah!”Whether or not this is the version that was ever presented in Vienna is open to debate, for the autograph score also shows that Mozart crossed out this single chord, an indication that he continued to change his mind about how this opera should end.29

Another weakness of the Don Juan subject matter is that the only really necessary scenes are those in which the hero and the Commander are brought together—the duel, the cemetery scene, and the banquet. To fill out the opera, the librettist has to bring in a great deal of nonessential material. Mozart, however, turned this material to advantage by setting it to some of his most effective music, such as Leporello’s “catalogue” aria, Don Giovanni’s “champagne” aria and serenade (“Deh vieni alla finestra”), Ottavio’s “Dalla sua pace” (a later addition to the score, which is unfortunately sometimes omitted in performance), Donna Anna’s brilliant “Or sai chi l’onore,” and Zerlina’s “Batti, batti”—to mention only a few of the outstanding arias in a score particularly rich in unforgettable melodies.

The ensembles in Don Giovanni are less important than in Figaro. It is significant that the duet “Là ci darem la mano,” the serenade trio “Ah taci, ingiusto core,” most of the great sextet in Act II (which Dent conjectures may have been originally intended for one of the finales in a three-act version), and even considerable portions of both finales belong to the class of static ensembles. They are like the quintet in the third act of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger or the canon in Beethoven’s Fidelio, where the singing, instead of advancing the action, is devoted to comment on or contemplation of the dramatic situation, developing its significance by means of music in a manner not possible in ordinary drama but eminently suitable to opera. One amusing touch in the last finale, comparable to the practice of representing actual persons among the figures of an imagined group in a painting, is the brief quotation of three melodies from popular operas of the day—Sarti’s Fra i due litiganti il terzo gode, Martín’s Una cosa rara, and Mozart’s own Figaro. These inserts, for wind instruments, make a formal counterpart to the little dances in the first finale, which are played by strings.

Although it is misleading to regard Don Giovanni as a Romantic opera in the nineteenth-century sense, nevertheless we cannot ignore one quality in the music that reveals Mozart in a different light from the all too common misconception of him as a merely elegant and graceful artificer in tones. The very opening measures of the overture—that “sound of dreadful joy to all musicians”—suggest at once the idea of the inexorable, superhuman power that opposes itself to the violent human passion of the hero. The overture does not outline the course of the action nor does it aim to depict the details of Don Giovanni’s character; it simply presents in monumental contrast the two opposing principles whose conflict is the essence of the drama. The demonic element of Mozart’s genius is even more strongly evident in the cemetery scene and in the terrifying apparition of the Commander’s statue in the last finale.30 At these places Mozart follows a long tradition of opera by introducing the trombones. The irruption of this peculiar demonic quality in many of Mozart’s late works—it is heard in some scenes of Die Zauberflöte and is even striking in the Requiem—suggests interesting speculations as to the possible course of his artistic development had he lived long enough to be fully exposed to the forces that brought about the Romantic movement in music in the early nineteenth century.

Mozart’s last comic opera was Così fan tutte; ossia, La scuola degli amanti; it is on an original libretto by Da Ponte and was first performed at Vienna on January 26, 1790.31 It is an opera buffa in the Italian manner, with two pairs of lovers, a plot centering about mistaken identities, and a general air of lighthearted confusion and much ado about nothing, with a satisfactorily happy ending. The music is appropriately melodious and cheerful, rather in the vein of Cimarosa, with a large proportion of ensemble numbers.32 Nowhere does the music suggest that Mozart felt constrained by the somewhat commonplace, old-fashioned libretto; rather, it is as though he were playing with the traditional types and combinations of the opera buffa, making out of them a masterpiece of musical humor lightly touched with irony, avoiding vapid superficiality but never introducing a tone of inappropriate seriousness. The last finale is an especially fine example of his art, an apotheosis of the whole spirit of eighteenth-century comic opera.

Following the death of Joseph II, Leopold II was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1790), King of Hungary (1790), and King of Bohemia (1791). The centerpiece of the theatrical entertainments presented on the occasion of his coronation in Prague was Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito. The contract for this opera, negotiated between the impresario of Italian opera in Prague and the Bohemian Estates, called for “una grand’ opera seria.”This, of course, marked a radical change from the opera buffa repertoire that had dominated the court-sponsored productions during Joseph II’s reign. Shortly after becoming emperor, Leopold II signaled his desire to offer opera seria and establish a permanent ballet troupe at the Burgtheater. To that end, he dismissed Da Ponte and the prima donna Adriana Ferrarese in 1790 and invited to Vienna an Italian troupe noted for its opera seria productions. Leopold II also restored the practice of celebrating birthdays and name days with theatrical productions, a practice that had been rigidly observed at the court during the first four decades of the eighteenth century.

The emperor’s fondness for the opera seria came from his repeated exposure to the genre during his many years in Italy, but Mozart had long since outgrown the form and style of the opera seria by the time he was asked to write an opera on Metastasio’s libretto (with substantial revision by Caterino Mazzolà) for the coronation at Prague on September 6, 1791.33 Although the first performance of La clemenza di Tito engendered some criticism (especially from the empress), the opera later attained a considerable degree of popularity.34 The whole score had been put together at a time when Mozart was preoccupied with work on Die Zauberflöte and the Requiem. With so little time to complete the opera, he enlisted the aid of a former pupil at Vienna to set the simple recitatives; the instrumentally accompanied recitatives, however, were composed by Mozart in Prague. As if the strain of satisfying the demands of his patron were not enough, Mozart at this time was suffering under financial distress; he was also worried about the health of his wife and was already ill himself.35 The wonder is that in such circumstances he could summon enough of his old powers of adaptability to produce music such as these arias and duets—music that has a certain stiff, old-fashioned nobility, appropriate to the formality of the occasion and the libretto.36 In the reworking of the libretto, the number of exit arias was greatly reduced. Of the ensembles, the finale added to Act I (which begins “allegro” and ends “andante”) is the most dramatic and is incidentally interesting on account of the use of the chorus as background for the soloists—a device Mozart had not hitherto employed. Two of the most important arias in this opera call for virtuoso parts for the basset clarinet (“Parto, ma tu, ben mio”) and the basset-horn (“Non più di fiori”); both were intended to be played by Mozart’s friend and fellow Mason, Anton Stadler, for whom the Clarinet Quintet (K. 581) and the Clarinet Concerto (K. 622) had been composed. No less interesting is the festive one-movement overture (composed by Mozart in Prague after he had completed the rest of the score), for here the essence of the opera—dramatic and musical—is captured within an instrumental form.37

The German Operas

Mozart’s first Singspiel was Bastien und Bastienne, composed at the age of twelve on a German translation of Favart’s vaudeville comedy of 1753 (which in turn had been parodied from Rousseau’s Le Devin du village) and first performed at Vienna in the garden of Dr. Anton Mesmer, the famous hypnotist. The charming songlike melodies and the simplicity of the style, in which some influence of the French opéra comique composers is discernible, have kept this little work alive, and it is still occasionally heard. Mozart had no further occasion to compose theater music to German words until 1779, from which year we have the unfinished Zaïde, a Singspiel evidently intended for performance at Salzburg, and three choruses and five entr’actes for Gebler’s play Thamos, König in Aegypten. Both of these works are notable for employing the device of melodrama, which Benda had recently introduced in Germany. Zaïde, in both subject matter and musical style, is like a preliminary study for Die Entführung aus dem Serail. Mozart himself was particularly fond of the Thamos choruses, which have a dignity comparable to what is heard in Gluck and Rameau. (The same religious and mystical mood is heard again in the second act of Die Zauberflöte, which deals with similar subject matter.) Der Schauspieldirektor (1786) was a little one-act comedy with music on the model of some of the early French opéras comiques, in which a rehearsal scene serves as a pretext to show off the talents of two rival female singers, who then fall to quarreling while a tenor tries to make peace. The closing number is a vaudeville final (strophic solos with refrain), like the finale of Die Entführung.

What Mozart had done for the opera seria in Idomeneo and for the opera buffa in Così fan tutti he did for the German Singspiel in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, which was performed at Vienna on July 16,1782, with immediate success.38 The libretto, arranged by Gottlieb Stephanie (the Younger) from a play by Christoph Bretzner, makes use of the Turkish background that was so popular in both serious and comic eighteenth-century opera.39 Interest in the exoticism of the East was fostered by political and military factors stemming from a series of wars that were waged between the Ottoman Empire and Austria, beginning in 1683 and continuing into the next century. By the 1760s the power of the Ottoman Empire had diminished to a point where the Austrians looked to their former enemy as a possible ally against an ever-increasing threat from Russia. Interestingly, between 1764 and 1781, some of the very years when Russians and Turks were at war, eleven operas were produced that can be classified as “Turkish abduction” operas.40 They include Gluck’s La Rencontre imprévue, Jommelli’s La schiava liberata (1768), Vogler’s Der Kaufmann von Smyrna (1771), and Haydn’s L’incontro improvviso (1775).41 All seem to have the same stereotypical plot:42

A young European woman of noble birth (often a Spaniard), separated from the nobleman she loves, is captured by Turkish pirates and sold as a slave to a sultan (Pasha). The sultan falls in love with her, but the Christian woman resists his advances and remains faithful to her lover. Meanwhile, her lover arrives at the seraglio and lays plans, with the help of a rather unwilling servant, to abduct her and to escape to their homeland by ship. The abduction, however, is thwarted by the sultan. He at first threatens to punish the lovers but then relents and permits them to return home. A final chorus exalts the Pasha for his act of kindness.

Die Entführung is not remarkable for originality, but it does offer sufficient possibilities for effective musical setting, especially in the character of Osmin, to whom Mozart required Stephanie to give a much more conspicuous role than he had in the original play, and for whom he wrote two of the best comic bass arias in the whole realm of opera.43 Osmin, servant of the nonsinging Pasha Selim, is loud, boastful, and bent on revenge—traits that underscore the image Mozart’s audiences associated with persons from the Islamic culture of the East.

Throughout his entire career, Mozart insisted that the cast of singers be chosen before he started to set a libretto to music, for his arias were almost always designed with specific singers in mind. In the case of Die Entführung, the role of Osmin was to be sung by Johann Ignaz Ludwig Fischer, who had become very popular with the Viennese since his arrival in the imperial city in 1780. Even after an opera’s premiere, Mozart frequently altered arias and ensembles to suit the cast for subsequent performances. For example, when Adriane Ferrarese del Bene was cast in the role of Suzanna for a 1789 production of Figaro, Mozart substituted two newly created arias to accommodate Ferrarese’s mezzo soprano range. Similarly, the finely wrought tenor aria “Il mio tesoro” heard in the original Prague production of Don Giovanni was replaced with “Dalla sua pace” for a Vienna production in which the tenor role was sung by a less skilled singer.

The music for Die Entführung is somewhat inconsistent in style; the hero and heroine sing big arias of the Italian sort, while their two servants have simpler song-like melodies—a division of labor quite in accordance with the theories of Johann Adam Hiller. Pedrillo’s “romanza” (no. 18), a strophic ballad inserted in the action like “Que le sultan Saladin” in Grétry’s Richard, has curious modulations by which Mozart perhaps intended to suggest oriental atmosphere. Other concessions to local color are found in the theme of the first chorus and in the addition of “Turkish” instruments (cymbals and bass drum) to the orchestra for the overture, one duet, and two choruses of Janissaries.44 The ensembles are not to be compared in either dramatic or musical importance with those of the later Italian comic operas, since the action of Die Entführung takes place almost entirely in spoken dialogue. On the whole, the melodic line is less ornate than in the Italian operas, and the phrases are noticeably shorter and more regular, in conformity with the less flexible construction of the German poetry.

What Mozart accomplished in Die Entführung was to raise the Viennese Singspiel at one stroke from a comparatively amateur level to a complex work of dramatic art, taking in (though, to be sure, not always fully assimilating) elements of Italian serious and comic opera and of French opéra comique, as well as the warmth and earnestness of German song.45 Moreover, he created a work, that, whatever its stylistic inconsistencies, is fresh and youthful in inspiration, and filled with a vitality and a beauty that have not faded to this day. The success this Singspiel had, not only in Vienna but also on other German stages, is impressive and contributed substantially to establishing Mozart’s reputation in other German cities and courts, especially in Prague and Berlin.46 When the work was added to the Dresden repertory in 1818, Carl Maria von Weber justified his actions to the public, remarking that Mozart reached the peak of his artistic experience with this work and “with the best will in the world, he could never have written another Entführung.”

We come now to Mozart’s last dramatic composition, that sphinx among operas, Die Zauberflöte, first performed on September 30, 1791.47 It was an immediate and lasting success at Vienna, thus realizing one of Mozart’s deepest desires; unfortunately, he did not live to enjoy the triumph for long. The libretto, at first sight, presents an extraordinary jumble of persons and incidents. The explanation of this state of affairs is somewhat complicated and has been further complicated by various widespread but apocryphal stories about the circumstances under which the work was written.

The librettist (though even this point has often been disputed) was Emanuel Schikaneder (1751–1812)—an actor, singer, dramatist, composer, and impresario—whom Mozart had come to know at Salzburg in 1780.48 Schikaneder began his career as an itinerant actor and director of a troupe that performed in southern German and Austrian towns. In 1780 he brought his troupe to Salzburg where they remained in residence for a number of years. Beginning in 1789 Schikaneder disbanded his troupe and moved to Vienna to take charge of the Theater auf der Wieden (Wiedentheater) located just outside the city walls of Vienna, where he offered to the public a mixed fare of Singspiele and plays.49 Included in these were plots of fairy tales and magic adventure in exotic settings, featuring spectacular tableaux and scene-transformations and often spiced with allusions to current events and personalities in Viennese life. Assisting Schikaneder were two multi-talented persons from southern Germany, Benedikt Schack (1758–1826) and Franz Xaver Gerl (1764–1827); they composed, sang, and acted. Among the seven Singspiele created prior to 1791 was Der Stein der Weisen oder Die Zauberinsel (1790), a heroic-comic pasticcio opera in two acts set to one of Schikaneder’s first “magic” opera librettos.50 Those who supplied musical numbers for the score include Mozart, Johann Baptist Henneberg (1768–1822), Schack, Gerl, and Schikaneder, with the last three named taking part in the production as members of the cast.51 These same five composers may also have contributed to the anonymous score for Schikaneder’s Der wohltätige Derwisch, produced in the spring of 1791 at the same theater.52

When Schikaneder proposed the subject of Die Zauberflöte, Mozart accepted it as an opportunity to create a real German opera, his first for the popular theater. In the manuscript, it is not called a Singspiel (despite its spoken dialogue) but a grosse Oper, something that might be translated as grand opera if that particular term had not been preempted by historians for a different use (see chapter eighteen).

Schikaneder, a kind of literary magpie, filched characters, scenes, incidents, and situations from others’ plays and novels and with Mozart’s assistance organized them into a libretto that ranges all the way from buffoonery to high solemnity, from childish faerie to sublime human aspiration—in short, from the circus to the temple, but never neglecting an opportunity for effective theater along the way.53 One of the more puzzling features of this work is the way in which the “good” characters apparently change into “bad” ones, and vice versa, beginning with the closing scene of Act I. The explanation usually assumed is that Schikaneder and Mozart at this point suddenly decided, for no evident good reason, to reverse the plot and transform the entire nature of the opera. But there is good weight of authority now to discredit this explanation or at least to restrict its scope.54 In the first place, the inconsistencies between the earlier and later parts of the libretto are not so great as they appear at first sight, not greater than might be expected in a plot that moves altogether in an atmosphere of magic and the marvelous. In the second place, there is no evidence in Mozart’s music that he felt a complete reversal of moral values was occurring at the end of Act I. It is rather as though the first part of the opera takes place in a neutral, one might say a pre-moral, realm; the appearance of Sarastro and the priests signifies the coming of higher, specifically human obligations, the transition from childhood to adulthood. Whether this new element came in as the result of a deliberate change of plan or had been tacitly foreseen from the beginning is a question that probably never will be finally answered.

One thing, however, is certain. Mozart and Schikaneder resolved to depict the realm of moral duties and virtues by means of Masonic symbols. Freemasonry was a force of great influence and considerable political importance in eighteenth-century Europe, counting among its members such distinguished men as Frederick the Great, Voltaire, Goethe, and Haydn. Both Mozart and Schikaneder were members of the Masonic order, and there is evidence in Mozart’s correspondence and also in his music of the deep impression its teachings had made upon him.55 The second act of Die Zauberflöte carries its hero, Tamino, and heroine, Pamina, through various solemn ordeals, undoubtedly veiled representations of the degrees of Masonic initiation, which they undergo successfully with the help of the priests and are then united.

One cannot hope to understand the libretto of Die Zauberflöte without a willingness to accept its externals as in some sense symbolical of profounder meanings.56 That such meanings exist is suggested by the respect this opera has always claimed from poets and philosophers as well as musicians. Goethe, for example, not only praised its theatrical effectiveness but also compared it with the second part of his Faust as a work “whose higher meaning will not escape the initiated.”57 Was this a reference simply to its Masonic features? Attempts have been made to interpret the opera in detail as representing not merely Masonic doctrines but actual persons and events associated with the lodges of Vienna in Mozart’s time.58 But such an interpretation, even if true, would not by itself account for the peculiar quality of the music.

Equally inadmissible is the assumption that Mozart simply poured forth great music in serene disregard of the inconsistencies or frivolous details of the libretto. Such a view can only ignore his whole career as an opera composer, for he was never uncritical of his texts and was always making changes suggested by his own dramatic instinct or experience of the theater.59 It is more reasonable to conclude that he saw in Die Zauberflöte an expression, partly in the guise of a fairy story and partly by means of Masonic or pseudo-Masonic symbols, of the same great ethical ideal of human ennoblement through enlightened striving in brotherhood that exercised such power over men’s minds at the time of the French Revolution and that later inspired Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and the second part of Goethe’s Faust. The exact interpretation of the significance of each person and event of the opera in this general plan must be largely a subjective matter. What concerns us here is that the idea itself operated so powerfully on Mozart that it not only enabled him to fuse all sorts of contradictory elements into unity—a trait that had always been fundamental to his genius—but furthermore compelled him to seek a new musical language for the stage. With the creation of that language, modern German opera was born. The way lay open to Fidelio, Der Freischütz, and the Ring.

When we look over the score of Die Zauberflöte, we are struck by the variety of musical types: simple, folk-like, strophic songs, elaborate coloratura arias, ensembles, choruses, a chorale, and long accompanied recitatives—a diversity corresponding to the diversity of characters and scenes in the story. Yet in hearing the opera, we are conscious that it is a unit. This homogeneity results not only from the fundamental dramatic idea but also from musical factors. If one excepts the two arias for the Queen of the Night, in which the style of opera seria is adopted for dramatic reasons, the music is essentially German rather than Italian. Little attention is paid to merely picturesque details of the text, and sensuous appeal is treated not as an end in itself but as a means of expression. German folksong quality is most apparent in the music performed by Papageno:60 in his solos (nos. 2, 20), in his duet with Pamina (no. 7), in the dance of the slaves (finale I), and in the duet (“Wir wandelten durch Feuergluten”) sung by Pamina and Tamino in the last finale. Less naive in language, more varied in form, richer in harmony, and filled with that combination of German fervor and Italian melodic charm, which we recognize as peculiarly Mozartean, are airs like Tamino’s “Dies’ Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” (no. 3),61 Sarastro’s “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” (no. 15), and Pamina’s “Ach, ich fühl’s” (no. 17). The dignified, earnest mood is especially felt in the march at the opening of Act II, the immediately following aria “O Isis und Osiris” with its choral refrain, and above all the choruses of the priests, to which the trombones lend a somber color. Elsewhere, too, the dark tone-color of the trombones, and of the basset-horns (tenor clarinets), is a striking feature of this score.62 A contrasting, though equally original, color effect is heard in the trios for boys’ voices at the beginning of each finale and in no. 16. In the duet of the armed men in the second finale, we have the chorale “Ach Gott vom Himmel sich’ darein,” sung in octaves and in a strict contrapuntal setting—a style quite novel in opera and producing here a climax of solemnity.

In the recitatives, Mozart solved a problem that the Singspiel had hitherto avoided, namely, that of finding an appropriate musical declamation for German dialogue. In the long scene between Tamino and the High Priest in the first finale, we hear how the melodic line—now declamatory, now breaking forth in arioso phrases—is fitted to the accents and rhythm of the language and at the same time suggests most vividly the contrasted feelings of the two interlocutors. Not a note is wasted; there are no meaningless formulae; every phrase plays its part in the dramatic structure of the dialogue, to which the harmonic progressions also contribute a significant share.63 Such recitative had not been heard in Germany since the time of Bach.

The unity arising from the pervasive national quality of the music is reinforced by various technical means; chief among them is the key scheme. The tonality of the opera as a whole is E-flat, and the principal related keys are the dominant, its dominant, and the two mediants. The first act begins and ends in C, with the middle section (nos. 3–7) in E-flat. The second act is divided, tonally, into three parts: nos. 9–13, C and its dominants; nos. 14–18, distant keys; nos. 19–21. returning to E-flat. The second finale is almost an epitome of the whole tonal plan: E-flat–Cm–F–C–G–C–G–Cm–E-flat.64

As Abert points out,65 particular dramatic significance attaches to certain keys: E-flat is consistently the tonality of the basic dramatic idea of the opera, G major that of the comic persons, and G minor that of the expression of pain. F major is the tonality of the “world of the priests,” though also of Papageno’s merry song “in Mädchen oder Weibchen”; C minor is the key of the “inimical dark powers” and also of the chorale.

Several motifs recur at different places in the opera and thus contribute to the effect of unity. Most conspicuous is the symbolic “threefold chord” of the overture, which we hear again at particularly solemn moments in connection with Sarastro and the ceremonies of initiation. The dotted rhythm of these chords in some form or other is always associated with the priests, though dotted rhythms are also employed in situations of danger for the expression of fear or excitement. Phrases from Sarastro’s “O Isis und Osiris” appear in the quintet no. 5 (at “O Prinz, nimm dies’ Geschenk” and “Zauberflöten sind zu eurem Schutz vonnöthen”) and in the duet no. 7 (at “Wir leben durch die Lieb’ allein”). The opening phrase of “Dies’ Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” turns up at a half-dozen unexpected places in the second finale. These and similar melodic reminiscences are not to be regarded as leitmotifs in the Wagnerian sense but as partly unconscious echoes of musical ideas that were in Mozart’s mind throughout the composition of the opera. Such reminiscences, not only within a single opera but also from one opera to another, are not infrequent in Mozart; they seem to be motivated by corresponding resemblances of dramatic ideas or situations. Certain stylistic details in Die Zauberflöte—the large proportion of themes built on notes of the triad, the frequent use of first inversions, deceptive cadences, and the melodic interval of the seventh—may be further mentioned as characteristic.66

In the operas of Mozart, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meet. He brought into the inherited traditions, forms, and musical language a new conception, that of the individual as a proper subject for operatic treatment. His characters are viewed from the point that most strongly emphasizes their individuality, namely, their love relationships. No composer has ever sung of human love in such manifold aspects or with such psychological penetration, and in every instance it is the person, not the abstract emotion, that is central. The change from the expression of an affect to the portrayal of a person is symbolized in the disappearance of the castrato, in the replacement of this impersonal instrument by the natural human voice. It is this shift of emphasis from the typical to the individual that most clearly separates Mozart from earlier opera composers of the eighteenth century and establishes his kinship with the Romantics. When finally, as in Die Zauberflöte, sexual love is subordinated to a mystic ideal and the individual begins to be a symbol as well as a person, we may well feel that a path has been opened that will lead ultimately to the music drama of Wagner.

1. For a comprehensive bibliography on Mozart as an opera composer, s.v. “Mozart” in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Some of the more important studies include: Dent, Mozart’s Operas (both editions);Abraham, “The Operas”; Grout, “Mozart and the History of Opera”; Deutsch, Mozart: A Documentary Biography; Eisen, ed., New Mozart Documents; Mann, The Operas of Mozart; Gianturco, Mozart’s Early Operas; Conrad, Mozarts Dramaturgie der Oper; Lippmann, ed., Colloquium; Szabolcsi, “Mozart et la comédie populaire”; Hunter and Webster, Opera Buffa in Mozart’s Vienna; Steptoe, The Mozart-Da Ponte Operas; Heartz, Mozart’s Operas; Nagel, Autonomy and Mercy: Reflections on Mozart’s Operas; Born, Mozarts Musiksprache: Schlüssel zu Leben und Werk. See also the Mozart-Jahrbuch and Neues Mozart-Jahrbuch.

2. The librettist has not been identified; attributions of authorship include Calzabigi, Coltellini, and Petrosellini. Cf. Angermüller, “Wer war der Librettist von La finta giardiniera?” and Gianturco, Mozart’s Early Operas, chap. 10.

3. La finta giardiniera was translated into German and presented as a Singspiel by traveling troupes, beginning around 1780. Spoken dialogue was substituted for the secco recitatives; the instrumentally accompanied recitatives were revised by Mozart to accommodate the German text. An eighteenth-century copy of this opera with Italian and German texts for all three acts was discovered a few decades ago. See Gianturco, Mozart’s Early Operas, and the introduction to W.A. Mozart: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, ser. 2, vol. 5.

4. The terms serenata, cantata, festa teatrale, and azione teatrale were used interchangeably in eighteenth-century writings. For example, Ascanio in Alba is subtitled festa teatrale by the librettist, Giuseppe Parini. Leopold Mozart, in a letter of July 19, 1771 (Mozart: Briefe, 1:424), referred to Ascanio as both a serenata and a theatrical cantata, and in a letter of August 31, 1771 (ibid., 1:436), he referred to it as both a serenata and an azione teatrale. Cf. Hortschansky, “Mozarts Ascanio in Alba,” and Gianturco, Mozart’s Early Operas, 100–108.

5. Their influence can be felt in Peter Winter’s Das unterbrochene Opferfest (1796), one of “the most successful German operas between Zauberflöte (1791) and Freischütz (1821).” See Henderson, “The Magic Flute of Peter Winter.” Many of the Mannheim opera scores were lost in the Austrian siege of Mannheim in 1795, and still others disappeared during World War II. For a study of the extant Mannheim operas, see Corneilson, “Opera at Mannheim, 1770–1778.”

6. It also presented him with an opportunity to become better acquainted with many of the operas created for the Mannheim court, for Carl Heinrich Joseph von Sickingen (councillor to the elector and his envoy in Paris) owned a collection of these scores and willingly shared them with the young composer during their frequent visits together. For more about this Mannheim collection and its possible influence on Mozart’s early operas, especially on Idomeneo, see Corneilson and Wolf, “Newly Identified Manuscripts from Mannheim.”

7. The genesis of this opera is revealed in Mozart’s letters to his father. See Heartz, “The Genesis of Idomeneo.”

8. The role of Idomeneo was sung by the tenor, Anton Raaff (1714–97), whose advanced age caused problems for Mozart’s setting of his aria texts. See Mann, The Operas of Mozart, chap. 13, and Heartz, “Raaff’s Last Aria.”

9. Here and throughout the opera, Mozart employs the tritone and diminished seventh chords to symbolize evil. See Heartz, “The Great Quartet in Mozart’s Idomeneo.”

10. Contrary to the usual practice of the period, Mozart himself composed the ballet music for Idomeneo, as he had done for Ascanio in Alba.

11. Examples are the recurrent descending fifth in the oboes and bassoons in Lila’s aria “Padre germani” (no. 1); the arpeggio figure for the flute in Electra’s “Tutte nel con vi sento” (no. 4); the many expressive interludes for woodwinds in Ilia’s “Se il padre perdei” (no. 11), which seem to envelop the solo as if with phrases of consolation; the spirited interplay of the voice with flutes and oboes in the coloratura passages of Idomeneo’s “Fuor del mar” (no. 12); the introduction of woodwinds before Electra concludes her aria “Idol mio” to provide a sense of continuity with the embarkation march that follows (no. 12a); the repetition of the climactic phrases of the chorus “Qual nuovo terrore” (no. 17) by the brasses and woodwinds; the solemn chorus of trombones and horns accompanying the voice of the Oracle (no. 28); and the effective contrast of the dominant-seventh chord for flutes, oboes, and bassoons which introduces the recitative immediately following.

12. Anderson, & ed., Letters of Mozart, 1:211; but cf.ibid., 1:208.

13. Ibid., 3:1150.

14. Ignaz von Mosel’s Über das Leben und die Werke des Anton Salieri, published in Vienna in 1827, is an exceptionally valuable biographical portrait of Salieri because it incorporates notes made by the composer—notes that are no longer extant. For a thorough discussion of late eighteenth-century Viennese operas in general and of Salieri in particular, see Rice, Antonio Salieri and Viennese Opera. See also Angermüller, Antonio Salieri; Swenson, “Antonio Salieri: A Documentary Biography.”

15. On the checkered career of Da Ponte, including the last thirty-three years of his life in the United States, see his Memorie (not always reliable), and Hodges, Lorenzo Da Ponte: The Life and Times of Mozart’s Librettist.

16. See Kelly, Reminiscences of Michael Kelly, of the King’s Theatre, 1:258ff

17. See Platoff, “A New History of Martín’s Una cosa rara

18. Excerpts from Zinzendorf’s diary are published in Michtner, Das alte Burgtheater. For this entry, see 405n. 66.

19. Hunter and Webster, Opera buffa in Mozart’s Vienna, 129.

20. On the authenticity of this accompanied recitative, see articles by Link and Zeiss.

21. Levarie, Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro; Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart; Levallois and Souriau, “Caractérologie musicale.”

22. Lewis, The Allegory of Love, 135.

23. Da Ponte, Memoirs (trans. by Abbott), 133. Cf. the tonadilla, which was “a little comedy in itself,” growing out of a finale.

24. This applies only to the Italian operas. The ensembles in Die Zauberflöte are, musically speaking, more in the nature of medleys than symphonic compositions. Cf. Engel, “Die Finali der Mozartschen Opern”; Rossell, “The Formal Construction of Mozart’s Operatic Ensembles and Finales”; Heartz, “The Creation of the buffo Finale”; Platoff, “Musical and Dramatic Structure in the Opera Buffa Finale.”

25. For a discussion of the term dramma giocoso, cf. Noske, “Don Giovanni: An Interpretation,” and Heartz, “Goldoni, Don Giovanni, and Dramma Giocoso.” See also chapter fifteen.

26. See Kunze, Don Giovanni vor Mozart, which contains the complete text of Gazzaniga’s opera.

27. For a study of eighteenth-century plays and operas based on the Don Juan story, see C. Russell, The Don Juan Legend before Mozart; Kunze, Don Giovanni vor Mozart; Rushton, W. A. Mozart’s Don Giovanni; Mila, Lettura del Don Giovanni; Pirrotta, Don Giovanni’s Progress; Miller, ed., Don Giovanni: Myths of Seductions and Betrayal.

28. On nineteenth-century interpretations of Don Giovanni and various “improvements” on the closing scene, see Dent, Mozart’s Operas (lst ed.), 265ff; (2nd ed.), 177ff.; E.T.A. Hoffmann, “Don Giovanni”; Kierkegaard, “The Immediate Stages of the Erotic.”

29. Robinson, “The Alternative Endings of Mozart’s Don Giovanni.”

30. Cf. Heuss, “Das dämonische Element in Mozarts Werken”; Clive, “The Demonic in Mozart.”

31. Da Ponte had initially offered this libretto to Salieri, but after setting a small portion of the text, Salieri abandoned the project, thereby paving the way for Da Ponte to offer it to Mozart. The discovery of Salieri’s setting of the first two numbers of the libretto was made by John Rice in the Musiksammlung of the Austrian National Library, where the autograph score survives. See B. A. Brown, W.A. Mozart: Così fan tutte, 10, and Rice, Antonio Salieri and Viennese Opera.

32. There are a number of these ensembles for singers of the same sex: see, for example, the three consecutive trios for male voices in Act I and the two duets for female voices at the opening of Act II.

33. The revisions involved a consolidation of three acts into two, the elimination of a number of arias, and a reworking of material to increase the number of ensembles (duets, trios, and finales). See Rice, Antonio Salieri and the Viennese Opera.

34. Interest in this opera waned after 1830, and only in the latter half of the twentieth century did it once again find favor with scholars and producers alike; its first performance at the Metropolitan Opera was staged in 1984. See King, Mozart in Retrospect; Mann, The Operas of Mozart; Moberly, “The Influence of French Classical Drama”; Rice, W.A. Mozart: La clemenza di Tito.

35. The sequence in which Mozart, with the help of Süssmayr, composed the music of La clemenza di Tito is discussed in Tyson, Mozart: Studies of the Autograph Scores. Cf.Tyson, “La clemenza di Tito and Its Chronology” and Durante, “The Chronology of Mozart’s: La clemenza di Tito Reconsidered.”

36. See, for example, Sesto’s aria “Deh, per questo instante solo” in Act II.

37. Cf. Floros, “Das ‘Programm’ in Mozarts Meisterouvertüren,” and Heartz, “The Overture to La clemenza di Tito as Dramatic Argument.”

38. See Mozart: Briefe und Aufzeichnungen for Mozart’s letters to his father (September and October 1781) concerning Die Entführung; they reveal his compositional processes and his views about text-music relationships. For an English translation of one of his letters written September 26,1781 concerning the bass arias, see Anderson, ed., The Letters of Mozart, no. 426. See also Bauman, W.A. Mozart: Die Enführung aus dem Serail.

39. Cf. Gluck’s Rencontre imprévue, the plot of which is almost identical with that of Die Entführung. See also Englander, “Glucks Cinesi’”; Preibisch. “Quellenstudien zu Mozarts Entführung”; Szabolsci, “Exoticisms in Mozart.”

40. For a discussion of one of the earliest “abduction” operas, Galliard’s The Happy Captive (1741), see chapter fifteen.

41. For another Turkish opera, see that of Joseph Martin Kraus in chapter twenty-four.

42. W. D. Wilson, “Turks on the Eighteenth-Century Operatic Stage and European Political, Military, and Cultural History,” 79. Wilson lists thirteen “Turkish” operas produced between 1735 and 1781, but two of them, including Hasse’s Solimano (1753), do not fully adhere to the plot as described below.

43. See Mozart’s remarks about these arias and other numbers in Die Entführung in a letter to his father dated September 26, 1781 (Anderson, ed., The Letters of Mozart, no. 426).

44. Piccolo and triangle were also added, but these are actually Western instruments. Janissary music (Turkish military band music) was well known in Europe in the eighteenth century, for these bands were heard frequently in connection with cultural exchanges and political events organized by ambassadors and envoys visiting there from Turkey. See M. Hunter, “The Alla Turca Style in the Late Eighteenth Century.”

45. One of those elements was his use of recitativo accompagnato (but not recitativo secco) in Die Entführung aus dem Serail.

46. For a list of first performances of Die Enführung aus dem Serail from 1782 until 1791, see Bauman, W.A. Mozart: Die Enführung aus dem Serail, 103–4.

47. On the autograph score, see studies by Gruber, Köhler, and Tyson. See also Buch, “Eighteenth-Century Performing Materials from the Archive of the Theater auf der Wieden,” on the only known copy of Mozart’s Zauberflöte that can be linked to Schikaneder’s theater.

48. See biography by Komorzyiński (1951).

49. The principal source that lists the repertory staged at the Freihaustheater is Deutsch, Das Freihaustheater auf der Wieden, 1787–1801. See also Spiesberger, Das Freihaus, 39–60.

50. Engravings of the scene designs for the original production of Der Stein der Weisen can be found in Emanuel Schikaneder’s Almanach für Theaterfreunde auf das Jahr 1791.

51. These same three men had roles in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte: Schikaneder played Papageno; Schack portrayed Taminio; and Gerl was cast as Sarastro. In a letter from Constanze Nissen to Schack dated February 15, 1826, she implies that Mozart contributed to the score; additional evidence supporting this attribution and the others cited above was uncovered by David J. Buch in 1996. A comparison of some numbers of Der Stein with Die Zauberflöte suggests that the earlier work influenced portions of the later one.

52. See Buch, “Mozart and the Theater auf der Wieden: New Attributions and Perspectives.”