FROM TIME TO TIME in the history of music, there have been composers whose works summed up the achievement of a whole epoch, making the final synthesis of a style: Palestrina and Bach are two outstanding examples. There have been other composers whose work incorporated not only the end of one style but the beginning of another as well: to this group belong Beethoven and Wagner. The early operas of Richard Wagner (1813–83) were the consummation of German Romantic opera of the nineteenth century; the later music dramas were in a style that, although retaining many features of what had gone before, nevertheless introduced innovations in both theory and practice.1 These innovations were not confined to the music but embraced the whole drama, and in working them out Wagner, who perceived all the implications of his ideas and developed them with typical German thoroughness, touched on many issues that were fundamentally involved with nineteenth-century thought. He is perhaps the only eminent composer whose writings have been considered important outside the conventional limits of the field of music. For him, indeed, these conventional limits hardly existed. Consequently, in order to understand his music, it is necessary to take into account his views on other subjects, including his philosophy of art in general and of the drama in particular. Whether one agrees or disagrees with these views is a question of the same order as whether one likes or dislikes the music; in either case, it is desirable to comprehend as well as to judge.2

The Early Operas

In music, Wagner was for the most part self-taught, for only during his days at Leipzig, did he receive formal musical training, first under the guidance of the cantor of St. Thomas’s church and then under that of the university, where he enrolled in 1831 as a music student.3 He became acquainted with the works of Beethoven and Mozart, and at the theater he heard the plays of Schiller and Shakespeare as well as the operas of Weber and Marschner.4 On the literary side, he also regarded E.T.A. Hoffmann to be an important literary influence on his work.

By the early 1830s Wagner had written some dramas and instrumental music, including the Symphony in C major, first performed in 1833. His two seasons (1833–34) as a chorus-master (répétiteur) at Würzburg brought him into close contact with the contemporary opera repertoire. Also during this same two-year period he composed Die Feen, his first completed opera, for which he wrote both the music and the libretto.5 This is a long work in three acts, with the usual subdivision into recitatives, arias, ensembles, and the like. A few traits of the music suggest his later works (Tannhäuser and Lohengrin), but the style on the whole is modeled after Beethoven, Weber, and Marschner.6 The libretto, based on a fairy tale by Carlo Gozzi, introduces all the fantastic and decorative apparatus of Romantic opera in profusion, but without the unifying power of a really significant dramatic idea.7 Nevertheless, the romantic idiom of the period is handled with great energy, aiming at big theatrical effects by conventional means. In fact, there is no technical reason why this opera could not have been performed in its entirety when written, for it is by no means an inexpert work; however, a production of the complete opera did not occur until five years after Wagner’s death.8

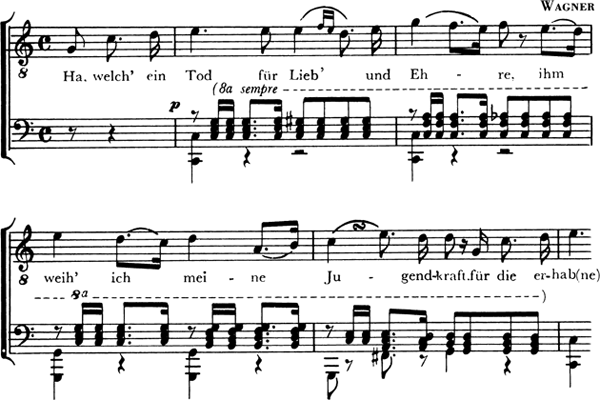

If Die Feen may be regarded as an essay in German Romantic opera, Das Liebesverbot, a two-act comedy, showed Wagner eagerly assimilating the French and Italian styles of light opera. Bellini’s Montecchi e Capuletti had aroused much enthusiasm at Leipzig in 1834 at a time when Wagner was temporarily in reaction against the alleged heaviness, lack of dramatic life, and unvocal quality of the typical German operas, as succinctly expressed in his 1834 essay Die deutsche Oper. His libretto for Das Liebesverbot is based on Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure; it is full of comic scenes and has some spoken dialogue. The music is a blend of Auber, Rossini, and Donizetti, with distinct traces of Meyerbeer in the finales, which often seem to strain terribly for effect. The melodies are florid, often with typically Italian cadenzas, and everything is repeated at great length as a means to extend the work. The best quality of the score is its liveliness and enthusiasm, though even this becomes wearisome after a time. Typical of the style of the opera as a whole is the duet in the first scene of Act II (example 22.1). Some of the crowd scenes faintly foreshadow the ending of Act II of Die Meistersinger; the duet of Isabella and Marianna in the first act and Marianna’s aria in the last act have a sultry erotic quality that looks forward to Richard Strauss. Das Liebersverbot was performed only once, and then very badly, at Magdeburg in 1836, with the composer conducting.9

From 1837 to 1839 Wagner was music director of the theater at Riga. There he began the composition of Rienzi, based on Bulwer-Lytton’s novel and inspired by a performance of Spontini’s Fernand Cortez, which Wagner had witnessed at Berlin in 1836. In the summer of 1839, he went to Paris; the first stage of that trip was a memorable stormy sea voyage to London, the impressions of which later influenced him in the composition of Der fliegende Holländer. The two-and-a-half years in Paris were a nightmare of failure, disappointment, and poverty. Even the efforts of Meyerbeer on his behalf did not obtain for him a hearing. Yet during this time, Wagner completed Rienzi and wrote Der fliegende Holländer, finishing the latter at the suburb of Meudon in August 1841.10 Rienzi was finally accepted by the Dresden Opera, where the first performance took place in October 1842. Wagner went to Dresden in the summer to supervise the rehearsals. The success of the work was immediate and overwhelming and led to a demand for Der fliegende Holländer, which was produced in January 1843. A month later, Wagner was appointed as a conductor for the Dresden Opera.

EXAMPLE 22.1 Das Liebesverbot, Act II, no. 7

Rienzi, as already noted (chapter eighteen), was a grand heroic-tragic opera in the fashion of the time, with just enough novelty to make it extremely popular.11 The reception of Der fliegende Holländer was less flattering: in externals, this work was less brilliant than Rienzi, and its inner dramatic significance went for the most part unperceived. This was not altogether the fault of the audiences, for Wagner himself had not yet perfected his technique. Der fliegende Holländer is essentially a German Romantic opera in the tradition of Marschner’s Der Vampyr or Hans Heiling (though without spoken dialogue) and is divided into the customary numbers, many of which are combined into large scene-complexes.12

Wagner took his version of the medieval legend of the Flying Dutchman from a tale by Heinrich Heine, adding features suggested by Der Vampyr. As in Der Freischütz, nature, animated by supernatural forces, is all-pervasive. This time it is not the forest but the sea: in the storm music, in the steersman’s song in Act I, and in the sailors’ choruses in Act III, Wagner set forth with all his power the impressions gathered in the voyage from Riga to London. These portions are not mere musical descriptions of the sea but are filled with symbolic meaning for the human drama.

In the story of redemption of the Dutchman from the curse of immortality by Senta’s love, Wagner for the first time clearly worked out the idea of salvation through love that became fundamental in his later dramas. It is stated in Senta’s Ballad (Act II), the central number of the opera and the one first composed. The ballad, a type of song that in earlier nineteenth-century opera had been, as a rule, only a set piece, here becomes the pivot of the whole dramatic and musical development. Its traditional two-part form is used to contrast the ideas of curse and salvation. The themes chosen are good examples of Wagner’s characteristic procedure of representing basic dramatic ideas by specific musical formulae: the opening motif forming an empty fifth, the stormy chromatics, and the diminished sevenths are set against the calm diatonic major melody of the second section.13 The ultimate salvation—already prophesied at the end of the overture—is symbolized in the finale of the opera by using the latter theme for an extended plagal cadence in D major.

These two themes (or rather theme groups) and their derivatives are used systematically in many other parts of the opera;Wagner had already adopted the device of the reminiscence motif but had not yet extended it to every portion of the work. The historical interest of Der fliegende Holländer lies not so much in this device—which, as we have seen, was not new with Wagner—as in the quality of the themes themselves, in the individuality of their harmonies, and in the way they seem to embody the essential dramatic idea, completing its expression and giving it depth and emotional power.

Another important number in Der fliegende Holländer is the C-minor recitative and aria of the Dutchman in Act I (“Die Frist ist um”), ending with his pathetic appeal for death (“Ew’ge Vernichtung, nimm mich auf!”), which is echoed mysteriously in E major by the voices of the unseen crew—a momentary shift of tonality made more striking by the immediate, implacable return to C minor in the orchestral coda. The long duet of Senta and the Dutchman in the finale of Act II is the climax of the drama, but its operatic style is an unfortunate lapse into an earlier and less individual musical idiom. Of the remaining numbers, it is necessary to call attention to the songs that are an integral part of the drama, such as the familiar “Spinning Song,” which opens Act II, with the women’s voices offering a pleasant contrast (in A major) to the dark colors of Act I and making an ideal prelude to Senta’s Ballad.14 The stanzaic form of these songs sets up a pattern anticipated by the audience, but the composer distorts that pattern by stopping the music before the final verse is concluded. An example of this occurs in the Helmsman’s Song that is cut short when the singer becomes too exhausted to continue to the end. Also of interest is the overture, which in the 1841 score Wagner concludes fortissimo with the Dutchman’s motif, but in a later revision, designed for a concert at Paris in 1860, he concludes more softly, substituting the Redemption motif (expressed in Senta’s Ballad) for that of the Dutchman. For this same 1860 performance, Wagner also transformed the ending of the opera’s final scene by repeating the concluding material of the overture.

In Tannhäuser (1845) Wagner sought to unite the two elements that he had developed separately in Der fliegende Holländer and Rienzi in order to clothe the dramatic idea of redemption in the garments of grand opera. His poem combined materials from a number of different sources. Its principal source is the medieval legend of Tannhäuser, a knight who sojourned with Venus in her magic mountain and later went on a pilgrimage to Rome to obtain absolution, which was refused him. “Sooner will this dry staff blossom than your sins be forgiven,” he was told by the pope. But the staff miraculously blossomed, a sign of God’s mercy. To this story Wagner added the episode of the song contest and the figure of Elizabeth, through whose pure love and intercession the miracle of salvation was effected. All this is cast in the traditional outlines of an opera with the customary theatrical devices. The division into numbers is still clear, though with more sweep and less rigidity than in the earlier works. There are solos (Tannhäuser’s song in praise of Venus, Elizabeth’s “Dich, teure Halle,” her prayer, and Wolfram’s song to the evening star), ensembles (especially at the end of Act II), choruses (the Pilgrims’ choruses for men’s voices, a favorite medium in nineteenth-century opera), the Venusberg ballet, and the brilliant crowd scene of the entrance of the knights and the song contest in Act II. Numbers such as these, treated with Wagner’s mastery of stage effect and in a style that audiences could easily understand, assured the success of Tannhäuser, though the new work did not arouse enthusiasm equal to that which had greeted Rienzi. Yet even where Tannhäuser is most operatic, it does not sacrifice the drama to outward show. The spectacular scenes are connected with the action and have a serious dramatic purpose; indeed, there are few operas in which form and content are so well balanced.

The portions of Tannhäuser that listeners failed to comprehend were just those considered most important in Wagner’s estimation, and most significant in view of his later development, namely the recitatives, of which Tannhäuser’s narrative of his pilgrimage to Rome (Act II) is the principal example. Here is a long solo containing some of the central incidents of the drama; it is certainly not an aria with regular melody and balanced phrases, but neither is it recitative of the neutral, declamatory type found in earlier operas (and elsewhere in Wagner also). It is a melody strictly molded to the text, a semi-realistic declamation of the words combined with expression of their content by means of a flexible line supported by an equally important harmonic structure. In addition to providing the harmony, the orchestra has certain musical motifs that, by reason of their character and their association with the text, are heard as a commentary on the words or as a further and purely musical expression of their meaning (example 22.2). This is the style that came to prevail almost exclusively in Wagner’s later works. It was not entirely new with Wagner—Weber had done something similar in Euryanthe—but he used it so extensively, wielded it so effectively, and built it so firmly into his whole theory of the music drama that he perhaps rightly ranks as its discoverer. To the original singers of Tannhäuser, as well as to the audience, it was a mystery. Even the famous soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, Wagner’s staunch friend from the beginning and one from whom he received much inspiration, confessed that she could not make head or tail of her role of Venus; and the tenor Joseph Tichatschek, though equally devoted to the composer, had not the slightest perception of his new dramatic aims. Little by little, however, a small section of the Dresden public began to sympathize; this group—significantly, it included few professional musicians—formed the nucleus of the future Wagner cult.

EXAMPLE 22.2 Tannhäuser Act III

The essential dramatic idea in Tannhäuser is the opposition of the world of sensual ecstasy and the world of ascetic renunciation, the former represented by Venus and her court, the latter by Elizabeth and the Pilgrims.15 Both Wagner’s expansion of the Venusberg ballet for the disastrous Paris performances of 1861 and his revision of the last finale to include the actual appearance of Venus served to accentuate the contrast between the two basic ideas of the opera.16 Wagner’s music embodies the character of each of these worlds with an imaginative grasp and intensity of utterance that are more remarkable than anything else in the whole score. His greatness as a composer lies just in this power of evoking in the listener’s mind such conceptions, in all their emotional depth and complexity, by means of music in which every detail is consciously or unconsciously directed toward the expressive purpose. In pursuit of his aims. Wagner found it necessary to rely more and more on the resources of harmony and instrumental color; as the aria diminished in importance, the orchestra rose correspondingly. This is evident in Tannhäuser, both in the thematic importance of the accompaniments and in the separate orchestral pieces. The introduction to the third act, depicting Tannhäuser’s pilgrimage, is one of those short symphonic poems of which there were to be more in the later works—Siegfried’s “Rhine Journey” in Götterdämmerung, for example, or the “Good Friday” music in Parsifal. The overture to Tannhäuser is a complete composition in itself and, like those of Der fliegende Holländer and Die Meistersinger, a synopsis of the larger dramatic and musical form to follow.

It has been noted that the first six completed operas of Wagner are grouped in pairs, and that within each pair, each member is in many ways complementary to the other.17 This is especially noticeable with Tannhäuser and Lohengrin. The latter was composed in the years from 1846 to 1848, though not performed until 1850 at Weimar, under Liszt’s direction. Its sources are found in folklore and Germanic legend, particularly in the anonymous medieval poem Lohengrin, written in the late thirteenth century, and in The Swan-Knight of Konrad von Würzburg, as retold in The German Legends of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.18 In Lohengrin, Wagner is concerned less with the tale itself or the historical setting and more with the timeless significance of the events portrayed. The characters, though adequately depicted as human, are at the same time agents or personifications of forces the conflict of which makes the drama. Thus Lohengrin may be said to represent divine love and its longing for reciprocal love and faith from humanity, while Elsa represents human nature incapable of the necessary unquestioning trust. Whatever meaning one may see in the story, the necessity of some interpretation in the sense suggested is unavoidable.

In keeping with this view of the drama, the musical setting of Lohengrin is altogether less spectacular than that of Tannhäuser; there are no sensational contrasts, and an extraordinary unit of mood prevails throughout. The system of reminiscence motifs is still further developed, not only in extent but also in the changed function of the motifs themselves: they are no longer used simply to recall earlier scenes and actions but to symbolize situations or abstract ideas. For example, the motif that some analysts label “the forbidden question,” first sung by Lohengrin as he lays the command on Elsa never to ask for his name or country, is a complete, periodic, eight-measure theme (example 22.3). It recurs, in whole or in part, throughout the opera wherever the situation touches pointedly on this prohibition: in the introduction to Act II, during the dialogue between Ortrud and Friedrich in the first scene, in the second scene at Ortrud’s hypocritical warning to Elsa against the “unknown” knight, at Elsa’s sign of doubt in the last scene of the act, and in the closing orchestral cadence; it comes into the duet of Act III, rises to full force as Elsa asks the fatal question, echoes again at the end of this scene, and is heard once more at Elsa’s entrance in the last finale. Other characteristic motifs are used in a similar way. The principle is not yet that of the Ring, where the motifs are shorter, essentially harmonic and rhythmic rather than melodic, and employed continuously in a symphonic web; nevertheless, Lohengrin carries the practice further than any preceding opera and clearly points the way to Wagner’s later style.

From the formal point of view, Lohengrin has shed many traces of the traditional division into numbers, as well as much of the distinction between aria and recitative. The new free declamation is the normal style in this work, except in a few places such as Elsa’s “Einsam in trüben Tagen” (and even here the three strophes of the solo are separated by choruses and recitatives), Lohengrin’s narrative in Act III, the Bridal Chorus, and the duet following this. The colorful orchestral prelude to Act III is often played as a separate concert number. Unlike the overture to Tannhäuser, the prelude to Lohengrin is in one mood and movement, representing (according to Wagner’s statement) the descent and return of the Holy Grail, the type of Lohengrin’s own mission, as we hear when the same themes and harmonies accompany his narrative in Act III. The A-major tonality of the prelude is associated with Lohengrin throughout the opera, just as the key of F-sharp minor is assigned to Ortrud and, as a rule, the flat keys to Elsa. The harmony of Lohengrin is remarkably diatonic; there is very little chromaticism of the sort found in the middle section of the “Pilgrims’ Chorus” or the “Evening Star” aria in Tannhäuser.

EXAMPLE 22.3 Lohengrin, Act I

The orchestration likewise contrasts with that of Tannhäuser: instead of treating the instruments as a homogeneous group, Wagner divides them into antiphonal choirs, often with the violins subdivided and the woodwind section expanded so as to make possible a whole chord of three or four tones in a single color. The effect, while less brilliant than in Tannhäuser, is at the same time richer and more subtle. Even in the last scene of Act II, showing the dawn of day heralded by trumpet fanfares and the procession to the minster, the sonority is restrained in comparison with the usual grand opéra treatment of such episodes.

The skillfully written choruses in Lohengrin are an important musical and dramatic factor. For the most part, the chorus is treated either as realistically entering into the action or else as an “articulate spectator” in the manner of Greek tragedy (especially in the second scene of Act I and the finale of Act III). The prominence of the chorus may have been suggested to Wagner by his study of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, which he revised for performances at Dresden in 1847.

Lohengrin is generally regarded as the last of the important German Romantic operas. It has many resemblances to Weber’s Euryanthe: the continuity of the music, the style of declamation, and the use of recurring motifs, as well as the plot and characters.19 At the same time, Lohengrin functions as a pivotal work, for on the one hand it represents the culmination of a half century of operatic achievements, while on the other it foreshadows the style of Wagner’s later music dramas.20 The juncture between these two phases of Wagner’s development is marked by a pause in musical creativity; five years separate Lohengrin from Das Rheingold, begun in 1853.

The Ring Cycle

In February 1848, when word spread that a political uprising in Paris had succeeded in a republic being proclaimed there, the news stoked the revolutionary fires that had, for some time, been smoldering in Dresden. Wagner became heavily involved with the revolution, as evidenced by a number of factors, not the least being the publication of his poem “Revolution” in April 1849. As a result of his revolutionary activities, along with a multitude of other difficulties caused by quarrels with his superiors, he was obliged to flee the city soon after the Prussian soldiers successfully crushed the Dresden uprising on May 8, 1849. Since there was a warrant out for his arrest, he quickly sought refuge at Weimar with Liszt, who helped him escape to Switzerland. For the next twelve years, he settled at Zurich; there he found leisure to clarify in his own mind some new ideas on music and the theater that had already been occupying him at Dresden and of which some intimations may be found in his earlier operas, Lohengrin especially. The result of these cogitations was a series of essays, including Das Kunstwerk der Zukunft (The Artwork of the Future) and the important Oper und Drama (published in 1851), which is a systematic account of the philosophy and technical methods by which all his subsequent works were to be governed.21 A knowledge of Oper und Drama is indispensable for anyone who seriously desires to understand these works—the Ring, Tristan, Die Meistersinger, and Parsifal—even though Wagner’s practice is not always consistent with his theories.22

The doctrines of Oper und Drama are best exemplified in Der Ring des Nibelungen, which consists of four consecutive dramas: Das Rheingold, shorter than the others, consisting of but a single act; Die Walküre; Siegfried;23 and Götterdämmerung (originally titled Siegfrieds Tod), the first part of the cycle to be completed. Altogether, the composition of the Ring occupied twenty years of Wagner’s life. Its subject combines two distinct Germanic myth cycles, the story of Siegfried and that of the downfall of the gods.24 In November 1848 Wagner wrote Siegfrieds Tod, a drama he expected to set to music at once, but as the subject grew in his mind, he felt the need for another drama to precede this, and accordingly he wrote Der junge Siegfried in 1851. Whereas Siegfrieds Tod had been called “a grand heroic opera,” Der junge Siegfried bore the simple subtitle “drama.” This change in terminology reflects a remark made by Wagner in his essay A Communication to My Friends (1851), in which he states that he no longer writes operas. Rather than coin a new term for the kind of work for the theater that he was creating, Wagner decided to settle on the somewhat simplistic generic term of drama, feeling that it best represented the viewpoint from which his works were conceived.

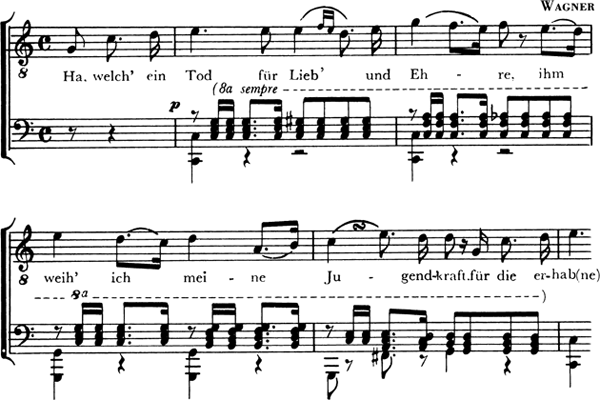

(COURTESY OF ARCHIV DES HAUSES WAHNFRIED, BAYREUTH)

Stage design by Wolfgang Wagner for Act III, scene i of Richard Wagner’s Die Walküre.

(COURTESY OF ARCHIV DES HAUSES WAHNFRIED, BAYREUTH)

Following the creation of the first two segments of the cycle, the work expanded still further: Die Walküre was required to lead up to Der junge Siegfried, and Das Rheingold was created as a general prelude to the whole. These two poems, in this order, were written in 1852, after which Der junge Siegfried and Siegfrieds Tod were revised into the present Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, respectively, the whole text being completed by the end of 1852 and published in a limited edition in 1853. Although some preliminary sketches for the music had been made prior to 1853, the composition was not begun in earnest until the text appeared in print. By 1857 the setting was completed through the second act of Siegfried. After an interim during which he composed Tristan and Die Meistersinger, Wagner resumed work on the Ring in 1865; the score of Götterdämmerung was not finished until nine years later.25 The first performances of the whole tetralogy inaugurated the Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

The story of the Ring is so familiar—or, at any rate, is so easily accessible in popular books of all sorts, not to mention the scores themselves—that there is no need to recapitulate it here. The material is taken not from folklore (as in Die Feen), or history (as in Rienzi), or even legend (as in Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser), but from mythology. The reason is not primarily that the myth is entertaining, but that it is meaningful.26 According to Wagner, the myth presents, in the simplest, most inclusive, and most concentrated form imaginable, the interplay of eternal forces affecting the relation of human beings to God, to nature, and to each other in society—in other words, living, eternal issues of religious, social, and economic importance, with which it is the duty of art consciously to deal. These issues are set before us in the myth, and consequently in the Ring, by means of symbols, represented by either objects (the Gold, Valhalla, the Sword) or persons (Wotan, Siegfried, Brünnhilde). It is the nature of a symbol to be capable of various interpretations, and although Wagner labored hard, both in the poem itself and in other writings, to make clear his own interpretation of the Ring, he did not fully succeed—partly because of some inconsistencies in his thinking and the obscurity of his literary style, but more because the symbols were so ambiguous that it was impossible to make a single definitive explanation of them. Many writers have tried to do so and have argued vehemently, each according to his own convictions, for or against the doctrines conceived to be embodied in the Ring. Still others regard any intentional preaching in art as either of no importance or else downright vicious and inartistic. There is no need at this day to add anything more to the enormous mass of controversial literature about Wagner. It is not within the scope of a book like this to investigate the alleged effects of his teaching, in the Ring or elsewhere, on European politics.27 That he did intend to teach—that his views of art and the theater impelled him in his operas to assume the role of prophet as well as musician—is a fact, whether one approves of it or not, but all that concerns us here is the consequences of that fact in his artwork itself.

It is not easy to dramatize abstractions. In the Ring, Wagner felt obliged to introduce some explanatory passages that slow down or interrupt the action of the play—for example, the long dialogue between Wotan and Brünnhilde in the second scene of Act II of Die Walküre. For the benefit of opera audiences, who are not particularly interested in metaphysics, these passages are often cut or shortened in performance. The same is true of the many repetitions of the story that occur from time to time, and other apparent digressions. All these matters have their justification, however, in Wagner’s theories; moreover, the leisurely pace of the action suggests the tempo of the long medieval epic poems from which the incidents were taken.

Another interesting reminiscence of these poetic models is Wagner’s employment of Stabreim or alliteration, instead of the more modern device of end rhymes:

Gab sein Gold mir Macht ohne Mass,

nun zeug’ sein Zauber Tod dem der ihn trägt!

(As its gold gave me might without measure, Now may its magic deal death to him who wears it!)

DAS RHEINGOLD, SCENE IV28

Wagner encountered Stabreim poetry in his reading of medieval Germanic literature. He was also aided in his study of this material by modern translations that had been published in the early part of the nineteenth century by a number of philologists, such as Jacob Grimm.29

The relation of music to drama is one of the subjects on which Wagner discourses in much detail in his writings. The first proposition of Oper und Drama is “The error in opera hitherto consisted in this, that a means of expression (the music) has been made an end, while the end itself (the drama) has been made the means.”30 It does not follow, however, that now poetry is to be made primary and music secondary, but rather that both are to grow organically out of the necessities of dramatic expression, not being brought together, but existing as two aspects of one and the same thing. Other arts as well (the dance, architecture, painting) are to be included in this union, making the music drama a composite or total artwork. This is not, in Wagner’s view, a limitation of any of the arts; on the contrary, only in such a union can the full possibilities of each be realized. The “music of the future,” then, will exist not in isolation as heretofore, but as one aspect of the Gesamtkunstwerk, in which situation it will develop new technical and expressive resources and will move beyond the point at which it has now arrived, a point beyond which it cannot substantially move in any other way.

This view was the consequence of a typical nineteenth-century philosophy. Wagner regarded the history of music as a process of evolution that must inevitably continue in a certain direction. The theory that the line of progress involved the end of music as a separate art and its absorption into a community of the arts is not without analogy to the communistic and socialistic doctrines of the period, with their emphasis on the absorption of the interests of the individual into those of the community as a whole.31 It is not surprising that some such view of the future of music should have arisen in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is plain enough to us now that the resources of music—that is, of the kind of music that had been evolving since Beethoven—were approaching their utmost limits at this time, and that these limits were in fact reached in the works of Wagner, Brahms, R. Strauss, and Mahler. It has been the mission of twentieth-century composers to recognize this situation and to create new musical styles, much as the composers of the seventeenth century had to do after the culmination of sixteenth-century polyphony in the works of Palestrina, Byrd, and Lassus. In discerning the approaching end of a musical style, therefore, Wagner was right. His error was in postulating the Gesamtkunstwerk as the only possible road for the future.

Wagner held that music in itself was the immediate expression of feeling, but that it could not designate the particular object toward which feeling was directed. Hence for him the inner action of the drama existed in the music, while the function of word and gesture was to make definite the outer action.32 This aesthetic is the theoretical basis of many features of the Ring and later works. For example, since the inner action is regarded as being always on a plane of feeling where music is appropriate and necessary, there is no spoken dialogue or simple recitative. Moreover, the inner action (unlike the outer) is continuous; hence the music is continuous. (In this theory, intermissions between the acts, and the performance of the Ring on four separate evenings instead of all at once, can be regarded only as one of Wagner’s reluctant concessions to human frailty.) Transitions from one scene to the next are made by means of orchestral interludes when necessary, and within each scene the music has a continuity of which the most obvious technical sign is the avoidance of perfect cadences. Continuity in music, however, is more than avoidance of perfect cadences. It is a result of the musical form as a whole,33 and since form in Wagner (as in any composer) is partly a function of harmonic procedure, this is an appropriate place to consider these two subjects together.

The statements most frequently made about Wagner’s harmony are (1) that it is “full of chromatics” and (2) that the music “continually modulates.” Both statements are true but superficial. Much of the chromaticism in the earlier works (for example, in the original version of Tannhäuser) is merely an embellishment of the melodic line or occurs incidentally in the course of modulating sequences. Many of the chromatic passages in the Ring, such as the magic sleep motif, are found in the midst of long diatonic sections. The impression that Wagner continually modulates is due in part to a short-breathed method of analysis based on a narrow conception of tonality, which tends to see a modulation at every dominant-tonic progression and, preoccupied with such details, overlooks the broader harmonic scheme.

A more comprehensive and illuminating view was set forth by Alfred Lorenz in his four studies entitled Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner (The Secret of Form in Richard Wagner), published between 1924 and 1933. Unfortunately, Lorenz, in the enthusiasm of discovery, tends to strain the facts to make them fit his theory. Using as a guide an idea expressed in Oper und Drama, namely that a poetic-musical unit or period “is determined by a principal key,” he attempted to show that Wagner’s music dramas are cast in definite musical forms, and that the formal clarity is evident not only in each work as a whole but also in the constituent sections, down to the smallest of them.34 Lorenz finds the structure of the music is inseparable from that of the drama, and one of its fundamental elements is the key scheme. Das Rheingold, for example, he regards as a large a–b–a form in D-flat, with an introduction in E-flat (the dominant of the dominant); D-flat is also the tonality of the Ring as a whole. Tristan is likewise in a three-part form, Acts I and III corresponding to the A section and Act II, the B section—though here the correspondence is one of themes and dramatic action, not of tonality. Lorenz finds that the three acts of Die Meistersinger make a huge a–a–b form, the first two being equal in length and the third as long as the first two together. These two forms, the Bogen (a–b–a, literally “bow”) and the Bar (a–a–b),35 are frequently exemplified also in the structure of scenes and smaller subdivisions; thus the fifteenth “period” of Act II of Siegfried (three measures before “Noch einmal, liebes Voglein” to the change of signature to four sharps at “nun sing”) is an a–b–a or Bogen in E minor (18 + 30 + 21 measures), and the introduction to Act II of Die Walküre is a Bar in A minor (introduction, 14 measures; two Stollen, 20 + 19 measures; Abgesang, 20 measures). Other form types (strophic, rondo) also appear, and many units are composed of two or more of the basic types in various modifications and combinations.36

Lorenz carried his type of analysis to the extreme, claiming that there is a “secret of form” within each of Wagner’s works. This claim went unchallenged for a number of years until Carl Dahlhaus and Patrick McCreless, among others, offered two quite different approaches to an analysis of Wagner’s compositional principles related to the Ring. Dahlhaus objects to Lorenz using “the period” to satisfy his own manner of analysis without taking into consideration that periods and scenes can be related to each other without having “to be subjected to any rule.”37 McCreless adopted more of a chronological approach for his investigation into the compositional process that pervades Siegfried. By contrasting the first two acts of this opera, which were composed and orchestrated between 1851 and 1865, with the third act, which was composed much later, between 1869 and 1871, he found that the first two acts reveal a more expansive equation of scenes and tonalities than that found in the relationship of “periods” and “keys” in Das Rheingold, whereas the third act exhibits a full-fledged symphonic treatment, such as would later develop in Götterdämmerung.38

Irrespective of how one chooses to analyze the Ring, it does not negate the essential orderliness, at once minute and all-embracing, of the musical cosmos of the Ring, as well as of Tristan, Die Meistersinge, and Parsifal. It is an orderliness not derived at secondhand from the text but inhering in the musical structure itself. Was Wagner fully aware of it? One is tempted to think not, since he says almost nothing about it in his writings. Yet whether conscious or unconscious, the sheer grasp and creation of such huge and complex organisms is a matter for wonder. It may be unnecessary to remark on the fact (if it is a fact) that Wagner’s creative processes were largely instinctive or unconscious does not of itself invalidate any analysis of his music. It is no essential part of a composer’s business to be aware, in an analytical sense, of everything he is doing.

Within the larger frameworks of order, and subsidiary to them, take place the various harmonic procedures that have given rise to Wagner’s reputation: modulations induced by enharmonic changes in chromatically altered chords and forwarded by modulating sequence; the interchangeable use of major and minor modes and the frequency of the mediants and the flat super-tonic as goals of modulation; the determination of chord sequences by chromatic progression of individual voices; the presence of “harmonic parentheses” within a section, related to the tonality of the whole as auxiliary notes or appoggiaturas are related to the fundamental harmony of the chord with which they occur; the systematic treatment of sevenths and even ninths as consonant chords; the resolution of dominants to chords other than the tonic; the combination of melodies in a contrapuntal tissue; and finally, the frequent suspensions and appoggiaturas in the various melodic lines, which contribute as much as any single factor to the peculiar romantic, Wagnerian, “longing” quality of the harmony—a quality heard in perfection in the prelude to Tristan und Isolde.

While the musical forms of Wagner’s dramas are determined in part by the harmonic structure, a more obvious role is played by the continuous recurrence and variation of a limited number of distinct musical units generally known as leitmotifs or leading motifs. The term leitmotif is not Wagner’s, though he did use the apparently synonymous word Hauptmotiv (principal motif). It seems likely, however, that Wagner suggested the word, as well as the system of analyzing his music dramas in terms of motifs, to Heinrich Porges, whose book on Tristan und Isolde, written from 1866 to 1877 (though not published before 1902), uses this method. The analysis of Wagner’s music in terms of leitmotifs was popularized by Hans von Wolzogen, first editor of the Bayreuther Blätter and author of many guides to the music dramas.39

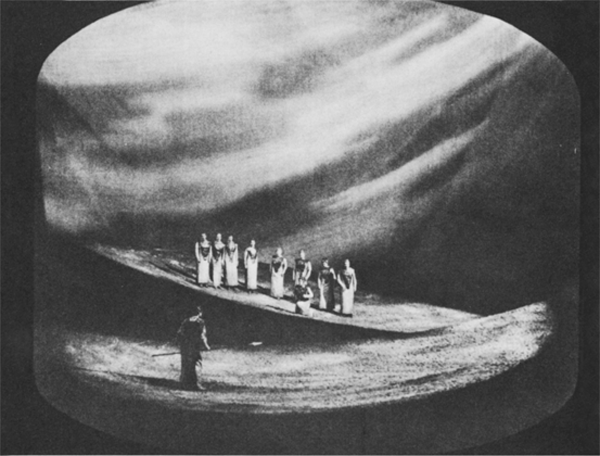

Different analysts distinguish, and variously name, seventy to two hundred leitmotifs in the Ring. Each is regarded as the focal point of expression of a certain dramatic idea, with which it remains associated throughout the tetralogy. The clue to the association of motif and idea is to be found at the first appearance of the former:40 for example, the Valhalla motif is first heard at the opening of the second scene of Das Rheingold, as the curtain rises to reveal the castle of Valhalla. Here, as usual at the first statement of a motif, Wagner repeats and spins out the phrase so as to impress it on the memory; moreover, there is an anticipation of the Valhalla motif at the end of the preceding scene, where its derivation from the Ring motif is obvious. The motifs are short and of pronounced individual character; they are often suggested by a pictorial image (as the fire motifs), or by association (as the trumpet figure for the sword motif), but each aims to convey not merely a picture but also the essence of the idea for which the visible symbol stands. In this capacity, the motifs may recur not simply as musical labels but whenever the idea recurs or is suggested in the course of the drama, forming a symphonic web that corresponds in theory, and generally also in fact, to the dramatic web of the action. The connection between the musical forms evolved from the dramatic forms. The motifs may be contrapuntally combined, or varied, developed, and transformed in accordance with the changing fortunes of the idea they represent. Relationship of ideas may be shown by thematic relationships among the motifs (example 22.4), though probably some of the resemblances are not intentional. Altogether, the statement, recurrence, variation, development, and transformation of the motifs is analogous to the working out of musical material in a symphony.

EXAMPLE 22.4 Motifs from the Ring

The list of leitmotifs compiled by Wagner enthusiasts in the late nineteenth century was done as a way of providing a guide to the understanding of the operas. The folly of this exercise, however, was caricatured by none other than George Bernard Shaw in The Perfect Wagnerite: “To be able to follow the music of The Ring, all that is necessary is to become familiar enough with the brief musical phrases out of which it is built, to recognize them and attach a certain definite significance to them, exactly as any ordinary Englishman recognizes and attaches a definite significance to the opening bars of God Save the Queen.”41

Since the inner meaning of the drama is found in the music, it follows in Wagner’s theory that the orchestra is the basic medium rather than the voices. In his phrase, the words “float like a ship on the sea of orchestral harmony.” Only rarely are the leitmotifs sung. As a rule, the voice will make a free counterpoint to the instrumental melody. The voice part, however, is always itself melodic, never merely declamatory as in recitativo secco; its line is so arranged as not only to give the correct declamation but also to reproduce the accent, tempo, and inflections appropriate to each character. Textual repetition is avoided. In theory there are to be no ensembles, especially in the old-fashioned sense where some voices are used only to supply a harmonic background, but this rule Wagner relaxed on occasion, as in the finale of Act II of Götterdämmerung and in the quintet of Die Meistersinger. Of Wagner’s genius as an orchestrator there is no need to speak here.42 His music is the realization of the full, rich, romantic sound ideal of the nineteenth century. Its peculiar texture is determined in large part by the nature of the melodic lines: long phrased, avoiding periodic cadential points (this in contrast to Lohengrin and earlier works), so designed that every note tends to move on without ever quite coming to rest.43 The full resources of symphonic style—counterpoint, orchestral color, and formal structure—are invoked. This in itself was not new in the history of opera, for many earlier composers (for example, Monteverdi in Orfeo) had done the same. But Wagner, besides having the immensely developed instrumental resources of the nineteenth century at his disposal, was conscious as no earlier composer had been of the drama and its “poetic intent” as the generating forces in the whole plan, and he was original in placing the orchestra at the center, with the essential drama going on in the music, while words and gesture furnished only the outer happenings. From this point of view, his music dramas may be regarded as symphonic poems, the program of which, instead of being printed and read, is explained and acted out by persons on the stage.

Wagner’s music dramas have been, and continue to be, as popular as any operas. The source of their appeal is primarily, of course, the music itself. Yet there are certain other factors that have at different times made for popular success in opera. One of these factors in the nineteenth century was the appeal to national pride, as in some of Weber’s and Verdi’s works. Such an appeal is indirectly present in most of Wagner’s operas insofar as they are founded on Germanic myths or legends, but this kind of nationalism is of little importance, since Wagner thought of his dramas as universal, dealing with what he called the “purely human,” not limited to Germans in the sense in which Der Freischütz was. Even Die Meistersinger, for all its reference to “holy German art,” is not narrowly patriotic or jingoistic in spirit. In his essay “Music of the Future,”Wagner makes clear his ideal that art forms should be unencumbered by barriers of nationality: “If differences of language prevent literature from attaining universality, music—that great language all men understand—should have the power, by dissolving verbal concept into feeling, to communicate the innermost secrets of the artist’s vision—especially when it is raised through the medium of a dramatic performance to that clarity of expression hitherto reserved to painting alone.”44

Another and more general basis of popular appeal in opera is stage spectacle. Wagner availed himself of this resource unstintingly, though always maintaining that every one of his effects grew of necessity out of the drama itself. It would be difficult to think of any beguiling, eye-catching, fanciful, sensational device in the whole history of opera from Monteverdi to Meyerbeer that Wagner did not appropriate and use with expert showmanship somewhere in his works.45 One has only to look at the poem of the Ring to see how prominent is this element; it has a large place also in Parsifal. In Tristan and Die Meistersinger, it is less in evidence, for these are dramas of human character and as such appeal directly to fundamental human emotions, with less need of spectacular stage effects. This quality of direct, human appeal is heard at only a few places in the Ring, as in the love scenes of Siegmund and Sieglinde (Die Walküre, Act I) and of Siegfried and Brünnhilde (Siegfried, Act III), or in the scene of Wotan’s farewell to Brünnhilde (Die Walküre, Act III), and when Wagner, like Wotan in this scene, put aside his concern with godhood to create the truly memorable characters of Walther, Eva, Hans Sachs, Isolde, and Tristan, he created two works that are likely to outlive all the pageantry and symbolism of the Ring.

Tristan und Isolde

The poem of Tristan und Isolde, begun at Zurich in 1857, is often regarded as a monument to Wagner’s love for Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of one of his most devoted friends during his years of exile.46 That there was both an intellectual and amorous relationship between these two people cannot be denied. In 1857–58, for example, Wagner composed five songs to poems by Mathilde, one of the rare instances of his willingness to set another person’s poetry to music. Two of these songs—“Träume” and “Im Treibhaus”—Wagner later described as “studies” for Tristan, for they are made up of thematic material that he later used in the opera. Then there are the letters exchanged between Mathilde and Wagner, which attest to the passionate feeling they shared for each other. One of these letters was intercepted by Wagner’s wife, Minna, shortly after the composer had completed the score of Act I of Tristan; the incident caused Minna to leave Zurich and return to Dresden.47 Wagner also left Zurich in August 1858 and sought refuge in Venice until March of the following year, when he once again returned to Switzerland. By August 1859 he had completed the opera.

Tristan was undertaken at a time when there appeared no prospect of ever bringing the Ring to performance, and it was Wagner’s hope that a less exacting music drama might have better prospects of success. But by now his ideas of what constituted a practicable work had so far outgrown the actual practice of the theater’s that Tristan experienced a similar fate and for a considerable period of time could not be produced. After more than seventy rehearsals at Vienna in 1862–63, it was abandoned as impossible. Finally, in 1864, the young king of Bavaria, Ludwig II, summoned Wagner to Munich and placed almost unlimited resources at his disposal. After careful preparation, the first performance took place at Munich on June 10, 1865, under the direction of Wagner’s pupil Hans von Bülow.48

The legend of Tristan and Isolde is probably of Celtic origin. In the early thirteenth century it was embodied by Gottfried of Strassburg in a long epic poem, which was Wagner’s principal source for his drama. Wagner’s changes consisted in compressing the action, eliminating nonessential personages (for example, the original second Isolde “of the white hands”), and simplifying the motifs. Some details were doubtless borrowed from other sources: the extinction of the torch in Act II from the story of Hero and Leander; the dawning of day at the end of the love scene from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet; Tristan’s delirium in Act III from Matthew Arnold’s poem; the love duet in the second act, which has some points reminiscent of a dialogue between Faust and Helena in the second part of Goethe’s drama; and the figure of Brangäne as watcher, who perhaps was suggested by Goethe’s Lynceus.49 The prominence of the motif of death, the yearning for fulfillment of love in release and annihilation, which broods over the whole drama—all were at least partly due to Wagner’s absorption in the philosophy of Schopenhauer, with whose works he had first become acquainted in 1854.50 But whatever the contributions of others, Tristan und Isolde is Wagner’s own. It is owing to him, and to him alone, that this is now one of the great love stories, living in the imagination of millions, along with the tales of Romeo and Juliet, Paolo and Francesca, and Launcelot and Guinevere.

The peculiar strength of the drama arises from the fact that external events are simplified to the utmost, so that the action is almost all inner and consequently is expressed almost wholly in music. The words themselves often melt into music, losing their very character as intelligible language, nearly superfluous in many places where the plane of expression is purely that of the emotions—as, for example, in Isolde’s solo at the end of Act III. “Every theory was quite forgotten,” wrote Wagner;“during the working out I myself became aware how far I had outsoared my system.”51

The three leading ideas of the drama—love, night, and death—are inseparable, but each one in turn is especially emphasized in each of the three acts. The magic potion of Act I is, in Wagner’s version, purely a symbol, figuring forth the moment of realization of a love already existing but unacknowledged. Isolde’s extinction of the torch is the symbol of Act II; the ecstatic greeting of the lovers leads into the duet “Descend upon us, night of love,” followed by the love-death music with the words “O could we but die thus together, endless, never to awaken!”The climax of the whole scene is in the song of Brangäne, offstage: “Lonely I watch in the night; you that are lost in the dream of love, heed the lonely one’s call: sorrow comes with awakening. Beware! O beware! For the night soon passes.” Few artists have so poignantly expressed what many human beings have experienced, the unutterably sorrowful realization in the midst of happiness that this moment cannot last. There is a comparable passage in the Arabian Nights:

Presently one of them arose and set meat before me and I ate and they ate with me; whilst others warmed water and washed my hands and feet and changed my clothes, and others made ready sherbets and gave us to drink; and all gathered round me being full of joy and gladness at my coming. Then they sat down and conversed with me till night-fall, when five of them arose and laid the trays and spread them with flowers and fragrant herbs and fruits, fresh and dried, and confections in profusion. At last they brought out a fine wine-service with rich old wine; and we sat down to drink and some sang songs and others played the lute and psaltery and recorders and other instruments, and the bowl went merrily round. Hereupon such gladness possessed me that I forgot the sorrows of the world one and all and said, “This is indeed life; O sad that ’tis fleeting.”52

The doom fated from the beginning is fulfilled. Tristan, reproached by King Mark, mortally wounded by Melot, is carried home to his castle of Kareol and dies as Isolde comes to him bringing Mark’s forgiveness. The love-death of Isolde herself, the celebrated Liebestod, brings the tragedy to an end.

Volumes could be, and have been, written about the music of Tristan und Isolde. The extreme simplification and condensation of the action, the reduction of the essential characters to only two, and the treatment of these two as bearers of a single all-dominating mood conduce to unity of musical effect and at the same time permit the greatest possible freedom for development of all the musical elements, unchecked by elaborate paraphernalia or the presence of anti-musical factors in the libretto. There are comparatively few leitmotifs, and many of the principal ones are so much alike that it is hard to distinguish and label them clearly. The opera’s power of musical expression, along with its gigantic structure, was greatly admired by many of Wagner’s contemporaries. Even Verdi, in an interview with the Berliner Tageblatt, expressed his profound admiration for this opera and its creator.

The dominant mood is conveyed in a chromatic style of writing that is no longer either a mere decorative adjunct to, or a deliberate contrast with, a fundamentally diatonic idiom, but is actually the norm, so much so that the few diatonic motifs are felt as deliberate departures, “specters of day” intruding into the all-prevailing night of the love drama. It is impossible here to enter into a comprehensive examination of the technical aspects of this chromaticism;53 we can only note that history has shown the “Tristan style” to be the classical example of the use of a consistent chromatic technique within the limits of the tonal system of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It was not only the climax of all romantic striving in this direction but also the point of departure for Wagner’s own later experiments in Parsifal; for the more sophisticated, external, ironic chromaticism of Richard Strauss; and for the twelve-tone system of Arnold Schoenberg, the conclusion of the whole style. The power of the Tristan chromaticism comes from its being founded in tonality. A feature of it is the ambiguity of the chords, the constant, immanent, felt possibility that almost any chord may resolve in almost any one of a dozen different directions. Yet this very ambiguity could not exist except for underlying tonal relations, the general tendencies of certain chord progressions within the tonal system. The continuous conflict between what might be, harmonically, and what actually is, makes the music apt at suggesting the inner state of mingled insecurity and passionate longing that pervades the drama. This emotional suggestiveness is accompanied throughout by a luxuriance of purely sensuous effect, a reveling in tone qualities and tone combinations as if for their own sake, evident in both the subdued richness of the orchestration and the whole harmonic fabric.

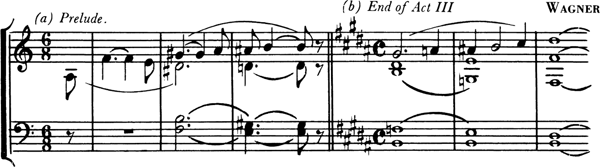

Such matters as these are felt by even the casual listener to Tristan and Isolde. What is less obvious, though it may be dimly sensed, is the complete formal perfection of the work. Here again the reader must be referred for details to the epoch-making study of Lorenz.54 The close correspondence of Acts I and III, with the resulting Bogen form of the opera as a whole, has already been mentioned. As to the tonality, Lorenz holds it to be E major—beginning in the subdominant (A minor) and ending in the dominant (B major). The tonic itself, in this view, is almost never sounded, this being at the same time an instance of the persistent avoidance of resolution in the harmony and a symbol of the nature of the love of Tristan and Isolde, which attains its satisfaction only in the ideal, not the actual world. The only extended E major portion of the opera is the scene of Tristan’s vision of Isolde in Act III. The complete first theme as announced in the prelude (measures 1–17) recurs only three times in the course of the opera, once at the climax of each act: at the drinking of the potion in Act I, after Mark’s question near the end of Act II, and at Tristan’s death in Act III. Its function is thus that of a refrain for the whole work. The continuity and formal symmetry, demonstrable in full only by a detailed analysis, are neatly epitomized by the fact that the opening chromatic motif of the prelude receives its final resolution in the closing measures of the last act (example 22.5).

EXAMPLE 22.5 Motif from Tristan und Isolde

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

After completing the score of Tristan and spending an unhappy season in Paris, marked by the scandalous rejection of the revised Tannhäuser at the Opéra (March 1861), Wagner lived for a year and a half in Vienna. With the failure of prospects for performing Tristan there, his fortunes reached their lowest ebb. His dramatic rescue by King Ludwig of Bavaria brought happier times, but six months after the successful first performance of Tristan, Wagner was compelled to leave Munich, owing largely to political jealousies on the part of the king’s ministers. He found a home at Hof Triebschen, near Lucerne, where he remained from 1866 until 1872. His first wife having died in 1866, he married Cosima von Bülow, daughter of Liszt and former wife of the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow, in 1870. Wagner’s chief activity in the early years at Triebschen was the composition of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

In 1845 Wagner made a prose sketch of Die Meistersinger, perhaps as a kind of comic pendant to Tannhäuser, and then he laid the project aside for sixteen years. Toward the latter part of 1861, Wagner planned the work anew, writing some parts of the music before the words.55 The score was completed in 1867, and the opera was first performed at Munich in the following year. The story has as its historical background the mastersinger guilds of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Nuremberg, whose song contests were conducted with strict adherence to the traditional rules and customs laid down by the Tabulatur. 56 Wagner not only incorporated many of these points but also borrowed several names and characters of real mastersingers, most notably Sixt Beckmesser and Hans Sachs, the cobbler-poet-composer who lived from 1494 to 1576.57 Likewise of historical interest are Wagner’ s use of an actual mastersinger melody (the march theme beginning at measure forty-one of the overture), the parody of the mastersingers’ device of Blumen (literally, “flowers”) or melodic ornaments in Beckmesser’s songs, and the paraphrase of a poem by the real Hans Sachs (the chorale “Wach’ auf!” in Act III). Yet Die Meistersinger is not a museum of antiquities but a living, sympathetic re-creation in nineteenth-century terms of an epoch of German musical history, with the literal details of the past illuminated by reference to an ever-timely issue, the conflict between tradition and the creative spirit in art. Tradition is represented by the mastersingers’ guild; the deadly effect of blind adherence to rules is satirized in the comic figure of Beckmesser, a transparent disguise for the Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, whose views and influence had made him one of the most persistent and conspicuous of Wagner’s opponents. The impetuous, innovating drive of the young artist, impatient of all restraints, is incarnated in the person of Walther von Stolzing, whose conflict with the mastersingers is finally resolved by the wisdom of Hans Sachs, the artist grown wise through experience. Sachs shows that neither tradition nor novelty can suffice by itself; they are reconcilable by one who understands the living spirit behind all rules of art and hence realizes that the new must constantly learn from the old, the old constantly absorb the new.

It is probably not fanciful to suggest that, in Walther and Hans Sachs, Wagner has drawn idealized portraits of two aspects of himself, and that the views of Sachs represent his own mature philosophy of art, set forth with deep insight and poetic beauty. One feature of this philosophy is the professed reliance on the judgment of “the people” as final arbiter in artistic matters. Das Volk was one of Wagner’s most beloved abstractions, one that he always carefully distinguished from das Publikum. One is sometimes tempted to believe that the distinction in his mind was simply between those who liked Wagner’s music dramas and those who preferred Rossini’s or Meyerbeer’s operas: the former comprising all the unspoiled virtues and sound instincts of the race, while the latter were unhealthy, misled, or corrupt. Yet there is a fundamental truth in the doctrine of the sovereignty of the people in art that Die Meistersinger proclaims, so long as one understands “the people” in the democratic sense of the word—not as a mob but as bearers of a profound, partly unconscious instinct that, in the long run, is apt to perceive and judge rightly.

In the last analysis, however, Die Meistersinger is not to be regarded as a treatise on the philosophy of art; its teachings are of little importance in comparison to the drama and the music. It is by far the most human, the most easily accessible, of all Wagner’s works. It has every requirement of good comedy: the simple love story of Walther and Eva, the charming scenes of David and the apprentices, the broadly comic strokes of Beckmesser’s serenade and his ridiculous attempt to steal Walther’s song for the contest. Above all is to be noted the character of Hans Sachs, Wagner’s greatest dramatic figure, who surveys the whole drama from the standpoint of one who through suffering has attained resignation, having learned to find joy in the happiness of others and the triumph of principles.

It is interesting to note that, with such a play as this, Wagner was led to compose a score that more nearly approaches the traditional outlines of opera than had any of his works since Tannhäuser. To be sure, the principle of symphonic development of a set of leitmotifs is maintained, and there is no return to the old-fashioned recitative, but withal there is an amount of formalization of which the listener is, perhaps, hardly aware, since it fits so naturally with the dramatic requirements. Like the Orpheus legend, the Meistersinger story is essentially musical in conception. Within its framework fall the four “arias” of Walther, the serenade of Beckmesser, Pogner’s “Address,” David’s song in Act III, and Sachs’s two monologues, as well as the formal overture and the chorale at the beginning of Act I. Even more operatic, though no less appropriate, are the apprentices’ choruses and the huge final ensemble in Act I, the uproariously comic crowd scene at the end of Act II, and the glorified mass finale with ballet and choruses in Act II. Then, too, there is the quintet in the third act, which is as much pure opera as anything in Donizetti or Verdi: an interpolated number in closed form (a–b–a) and a remote key (G-flat), which does not directly further the action but does have thematic connection with the rest of the work—a number that, in a word, would be out of place in the strict theoretical form of the music drama but is justifiable here on the same grounds that justify the canonic quartet in Fidelio or some of the ensembles of Don Giovanni.

It is a sign of Wagner’s versatility that, at the same period of his life, he could compose two works that differ so much not only in dramatic plan but also in musical style as do Tristan and Die Meistersinger. At the same time, there are certain features that these two operas hold in common, most especially the theme of forbidden love. Both the historical background and the nature of the subject matter of Die Meistersinger are reflected in the diatonic quality of most of the music, in a certain squareness of rhythmic structure, and in simplicity of idiom. The chorales, the many melodies of folk-like cast, the fugal section, and the contrapuntal combination of three principal themes in the overture, as well as the contrapuntal style of the finale and of many other passages—all seem to contain or suggest the very traits and forms that have always been most typical of German music. By contrast, the freer, more chromatic individual Wagnerian touch is heard in the love scenes and in the monologues of Hans Sachs. The beautiful orchestral prelude to the third act is not only the quintessence of the musical style but also the high point of the drama, the complete, living description of the noble character of Sachs; there is no better example of music as the heart of dramatic life, the true carrier of the inner action of the play.

The essentially musical character of the drama in both Tristan and Die Meistersinger is shown significantly by the fact that in both these works the musical forms are clearer and more comprehensive than anywhere else in Wagner. This is, of course, only another way of saying that these two works come as close as possible to the ideally perfect union of music and drama within the Wagnerian system. The form type most prevalent in Die Meistersinger is the Bar, of which five examples should be especially noted: (1) Beckmesser’s serenade in Act II is a pedantically correct example of two identical Stollen and an Abgesang, the whole being twice repeated to make a song of three strophes; (2) Walther’s first song before the mastersingers, “Am stillen Herd,” is a Bar in which the two Stollen are almost, but not quite, identical; (3) Walther’s trial song, “So rief der Lenz,” is a more extended Bar with two distinct themes in each Stollen, carried on grimly to the end in spite of the uproar of opposition from his audience; (4) in Walther’s dream song, the first version of the Prize Song, the two Stollen are not identical, the second being altered so as to cadence in the dominant; and (5) in the final version of the Prize Song, the melody is further extended and the differences between the two Stollen are likewise greater, though still without loss of the essential felt likeness.

In addition to many other instances of Bar form, some shorter and some longer than the above, the opera as a whole exemplifies the same structure: anyone who will take the trouble to compare Acts I and II, either with or without the help of Lorenz’s outline,58 will discover that there is a detailed parallelism of the action, and that furthermore in most cases each scene in the second act is a parody of the corresponding scene in Act I—a relationship already foreshadowed by the overture, in which the themes of the middle section parody those of the first. Acts I and II thus form two Stollen, of which Act III is the Abgesang. The whole opera is rounded off by the thematic and tonal correspondence of the beginning and the ending; Lorenz notes that the entire finale, from the entrance of the mastersingers on, is an expanded and varied reprise of the overture.59

After Die Meistersinger, Wagner turned his attention to completing the Ring and building a Festspielhaus. Plans for this new kind of theater, dedicated solely to the presentation of his music dramas, had been described by Wagner in letters and essays as early as the 1850s. Those plans materialized in 1872 with the laying of the foundation stone on land donated by the town of Bayreuth. In the same year, Wagner moved his family to Bayreuth and completed the score for the Ring, whose first full performance was given in 1876 to inaugurate the festival theater.60 The premiere was quite successful (even though some of the mechanical items did not operate as well as expected), but the deficit incurred in this undertaking was considerable, causing the second Bayreuth production of the Ring to be delayed by twenty years. In the meantime, there occurred many and varied international productions of the Ring, some with the original stage sets and costumes on loan from Bayreuth.

Parsifal

Wagner’s last music drama, a Bühnenweihfestspiel (a “stage-consecrating festival drama”), was composed between 1877 and 1882 and created exclusively for the Bayreuth theater, where the first performance took place in 1882, a year before Wagner’s death. The sources from which the Parsifal drama is drawn are even more varied than those of the earlier works. The convergence of many lines of philosophic thought and the complex and often obscure symbolism of the persons and events make this the most difficult of all Wagner’s music dramas to comprehend, even though the outer action is comparatively simple.61 The legend of the Holy Grail (already touched upon in Lohengrin and some other uncomposed dramatic sketches) is combined with speculations on the role of suffering in human life. The central idea is again that of redemption—this time not through love, but by the savior Parsifal, the Pure Fool, the one “made wise through pity.”62

No doubt the complexity of the poem is responsible for the music being less clear in formal outlines than that of either Tristan or Die Meistersinger. There is sufficient resemblance between the first and third acts to delineate a general a–b–a structure, but neither the key scheme nor other details of the various scenes are as amenable to analysis as in the case of the other two works. The music, like that of Tannhäuser, depicts different worlds of thought and feeling in the sharpest possible contrast, but whereas in Tannhäuser there were two such worlds, in Parsifal there are three. One of these is the realm of sensual pleasure, exemplified in the second act: the magic garden and the Flower Maidens of Klingsor’s castle, with Kundry as seductress under the power of evil magic. The confrontation between Kundry and Parsifal builds to the climactic scene of the “kiss,” the dramatic focus of the entire opera. If the music for these scenes is compared with the ebullient eroticism of the Venusberg music in Tannhäuser or the glowing ardors of the Siegfried finale, there may seem to be a slight falling off in Wagner’s earlier elemental power. Nevertheless, the musical setting provides the degree of contrast needed with the first and third acts, in which are opposed and intermingled the worlds of Amfortas and of the Grail, the agonizing penitent and the mystical heavenly kingdom of pity and peace. The Amfortas music is of the utmost intensity of feeling, expressed in richness of orchestral color, plangency of dissonance, complexity and subtlety of harmonic relationships, and a degree of chromaticism, which carries it more than once to the verge of atonality. The Grail music, on the other hand, is diatonic and almost church-like in style. The very opening theme of the prelude (known variously as the “Love Feast” theme or as the motif of sacrament), a single-line melody in free rhythm, is reminiscent of Gregorian chant; the Grail motif is an old “Amen” formula that was in use at the Royal Chapel in Dresden (example 22.6)

One feature of the Grail scenes in Parsifal deserves special emphasis, namely, the expertness of the choral writing that occurs in the choral scenes of all three acts. One does not ordinarily look to opera composers for excellence in a field of composition that has been chiefly associated with the church and the peculiar technique of which has not always been grasped by even some of the greatest composers. Wagner’s distinguished choral writing in Lohengrin, Die Meistersinger, and above all in Parsifal is therefore of interest; in particular, the closing scenes of Acts I and III of Parsifal recall the Venetian composers of the later sixteenth century, with their fine choral effects and the device of separated choirs, with the high and low voices giving an impression in music of actual space and depth.63

Another important feature of this score is Wagner’s use of what, for the lack of a better description, has been called the “interrupted song.”This device has already been discussed above in relation to Der fliegende Holländer, but here it assumes an even greater dimension. In Act I, Walter’s “Trial Song” is interrupted by a discussion among the masters about his performance. A second and more extensive use of this device can be found in Act II, scenes vi and vii, in which three different songs—the Cobbler’s Song, Beckmesser’s Serenade, and the Nightwatchman’s Song—are interrupted by dialogue and even by a fight scene.64

EXAMPLE 22.6 Motifs from Parsifal

In 1880 Wagner sent a letter to Ludwig II in Munich, in which he declared that performances of Parsifal would be restricted to the Bayreuth theater. He justified his actions by referring to the solemnity of the theme and the use of Christian religious symbols, elements that should not be brought forth on the unhallowed stages of the entertainment world. In his last important essay, “Religion und Kunst” (1880), Wagner further amplified his thoughts on religion and art as the two basic needs of humankind; he also reaffirmed the role of music in communicating feelings and emotions. The “religious” character of the Parsifal performances, so much a part of the Bayreuth festivals, has also been carefully maintained in other opera houses, even though the statute of performance limitation expired in 1914.

In attempting to estimate the significance of Wagner in the history of opera, one must first of all acknowledge the man’s unswerving idealism and artistic integrity. No matter how open to criticism some aspects of his personal conduct may have been, as an artist he stood uncompromisingly for what he believed to be right. He fought his long battle with such tenacity that his final success left no alternative for future composers but to acknowledge the power of the Wagnerian ideas and methods, whether by imitation, adaptation, or conscious rebellion. His form of the music drama did not, as he had expected, supersede earlier operatic ideals, but certain features of it were of permanent influence. Chief among these was the principle that lay at the basis of the Gesamtkunstwerk idea—namely, that every detail of a work must be connected with the dramatic purpose and serve to further that purpose. Wagner is to be numbered among those opera composers who have seriously maintained the dignity of drama in their works. In addition, many of his procedures—for example, the parallel position of voice and orchestra, the orchestral continuity, and the symphonic treatment of leitmotifs—left their mark on the next generation or two of composers. Other matters, however, were less capable of being imitated. Wagner’s use of Nordic mythology as subject matter and his symbolism were so individual that most attempts to copy them resulted only in unintended parody.65

It would not have been his wish to be remembered primarily as a musician, but the world has so chosen, and the world in this case has probably understood the genius better than he understood himself. The quality of Wagner’s music that has been the cause of its great popularity has been equally the cause of the severest attacks upon it by musicians: that it is not pure, absolute, spontaneous music, created for music’s sake and existing in a realm governed only by the laws of sound, rhythm, and musical form. Wagner is not, like Bach or Mozart, a musician’s musician. For him no art was self-sustaining. Music, like poetry and gesture, was but one means to a comprehensive end that can perhaps best be defined as “great theater.” Granted this end (which may or may not be conceived as a limitation), it is hardly possible to deny the adequacy of Wagner’s music in relation to it. The music not only possesses sensuous beauty but also can suggest, depict, and characterize a universe of the most diverse objects and ideas. Above all is its power—by whatever aesthetic theory one seeks to explain it—of embodying or evoking feeling, with a purity, fullness, and intensity surely not surpassed in the music of any other composer. Such emotion is justified by the grandiose intellectual conceptions with which it is connected and by the monumental proportions of the musical forms in which it is expressed. In this monumental quality, as well as in the characteristic moods, aspirations, and technical methods of his music, Wagner is fully representative of the time in which he lived.

1. A list of Wagner’s operas and music dramas is given below:

| TITLE | FIRST PERFORMANCE |

|---|---|

| Das Liebersverbot | Magdeburg, 1836 |

| Rienzi | Dresden, 1842 |

| Der fliegende Holländer | Dresden, 1843 |

| Tannhäuser | Dresden, 1845 |

| Lohengrin | Weimar, 1850 |

| Tristan und Isolde | Munich, 1865 |

| Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg | Munich, 1868 |

| Der Ring des Nibelungen | |

| I Das Rheingold | Munich, 1869 |

| II Die Walküre | Munich, 1870 |

| III Siegfried | Bayreuth, 1876 |

| IV Götterdämmerung | Bayreuth, 1876 |

| [first complete performance of Der Ring] | Bayreuth, 1876 |

| Parsifal | Bayreuth, 1882 |

| Die Feen | Munich, 1888 |