Russia and Neighboring Countries

RUSSIA

In the Soviet Union during the 1920s, two principal kinds of new operas were being performed: the traditional, conservative works supported by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians, and the progressive, avant-garde works promoted by the Association for Contemporary Music. The former group included operas commemorating battles and revolutions (e.g., For Red Petrograde, 1925, and The Storming of Perekop, 1927) and operas from the international repertoire revised to capture the revolutionary spirit (e.g., Tosca revised as The Struggle of the Commune, 1924). The latter group involved works by Soviet composers who were truly innovative and by outstanding non-Soviet composers, such as Berg and Krenek.

An opera that certainly moved away from any traditional mold was Nos (The Nose) by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–75),1 first performed at Leningrad on January 18, 1930.2 This satirical comedy, based on a story from Gogol’s St. Petersburg Tales, concerns a government official who has lost his nose. In its detached state, the Nose assumes an elusive identity, appearing in the most improbable situations. Ultimately, the Nose is caught, returned to its owner, and restored to its proper position. The score conveys the witty and eccentric text, with its fast-paced recitatives, angular and rhythmically complex vocal material, and sparsely scored music for the orchestra that explores the extremes of range and timbre, and harsh dissonances. Although recent performances of The Nose have shown it to be a brilliant theatrical entertainment, the initial performances of the opera met with mixed reactions, causing it to be eliminated from the stage until the Moscow revival in 1974.

The formation of the Composers Union in 1932, essentially a merging of the two organizations mentioned above, allowed the Soviet Union to exercise the ubiquitous power of the state on behalf of certain kinds of music and opera.3 This influence, together with the manner in which the musical life of the country was organized, tended to produce a body of Soviet music cut off from, and apparently largely indifferent to, the various contemporary “advanced” currents in western Europe and the Americas. The officially promoted ideals required, among other things, that music should be treated as the possession of the entire people rather than of a musical elite only; that its material should be sought in, or shaped by, the music of the people of its own country or region; that it should emphasize melody and be written in a style not too difficult for general comprehension; that it should be “optimistic” in spirit; and that its subject matter—where a text was involved—should affirm socialist ideals. This policy naturally encouraged production of a great many symphonic poems, ballets, choruses, and operas distinguished rather for massive size and suitable political intentions than for musical vitality. At the same time, this official policy also aimed at stimulating the development of popular and, most especially, of regional musical life within the Soviet Union, thereby enriching the musical language of the country from genuine Eastern folkloristic sources.

A work long regarded as a model for Soviet opera was Tikhy Don (The Quiet Don) by Ivan Dzerzhinsky (1909–78), first performed at Leningrad in 1935 and subsequently with great success all over the country. This work appears to hold a position in the history of Soviet opera comparable to that of Moniuszko’s Halka in Poland or Erkel’s Hunyady László in Hungary. Its patriotic subject is treated in accordance with Dzerzhinsky’s conviction that “everything that is lived by the people” can be expressed in opera, but that this must be done “in artistically generalized, typified figures, avoiding the pitfalls of naturalism.”4 The music is technically naive, simple in texture, predominantly lyric, containing many melodies that suggest folksong without actual citation and having a few “modern” touches of harmony and rhythm. A similar work, once even more highly regarded by Soviet critics, was Dzerzhinsky’s second opera, Podnyataya tselina (Virgin Soil Upturned, 1937).

Dzerzhinsky’s early works were representative of a trend in the 1930s toward the Stalinist “song opera,” of which one of the best examples is V buryu (Into the Storm, 1939) by Tikhon Khrennikov (b. 1913). The “song opera,” as a type, was subject to certain inherent weaknesses, principally the lack of clear, individual characterization through recitatives and ensembles, and the general absence of sharply defined dramatic contrasts. Into the Storm has been classified as a “socialist realist” work, primarily because of its focus on melodic and rhythmic material related to folk and urban songs. One unusual aspect of this particular opera is the inclusion of a brief speaking part for the character representing Lenin. Other notable operas by these two composers include Dzerzhinsky’s Sud’ba cheloveka (The Fate of a Man, 1962) and Khrennikov’s Mat (Mother, 1958). Mother was performed for the commemoration of the fortieth anniversary of the October Revolution. The libretto is drawn from a story by Maxim Gorky that tells of an earlier revolution, namely that of 1905; to accentuate the revolutionary atmosphere, the composer introduced some old revolutionary songs.

Stalin’s pointed approval of The Quiet Don coincided with a blast of official wrath at Shostakovich’s second opera, Ledi Makbet Mtsenskogo uezda (Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District).5 When this tragic-satirical opera in four acts was presented at Leningrad in 1934, it was praised at home and soon made its way abroad (being staged, for example, at Cleveland in 1935 and at London in 1936). Initial comments about the opera ranged from “a work of genius” and “high artistic worth” to “a reflection of correct Party policy” and “a creation that surpasses art in capitalist countries.”6 Two years later, following a performance of Lady Macbeth attended by Stalin, an article in Pravda denounced this opera as “confusion instead of natural human music,” unmelodic, fidgety, and neurasthenic, and moreover bad in that it tried to present a wicked and degenerate heroine as a sympathetic character. What had apparently shocked Stalin was the sexually explicit language and equally explicit music. Needless to say, Lady Macbeth promptly disappeared from Soviet theaters.

The libretto for Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District comes from an 1865 novella of the same title by Nikolay Leskov. The central character, Katerina Izmailova, is a merchant’s wife whose frustrations with Russian provincial life lead her to commit adultery, murder, and finally suicide. Shostakovich softens Leskov’s tale and projects the highly emotional but deeply sensitive Katerina through a lyrically intense vocal line, a lyricism that is meant to clash with the music portraying the other characters, which is brutal, lusty, vivid in the suggestion of cruelty and horror, full of driving rhythm and willful dissonance. As in other works of his early period, Shostakovich excels here in two idioms: a nervously energetic presto, thin textured, tonally erratic, and rhythmically irregular; and a long-spun adagio, mounting with clashing contrapuntal lines to sonorous climaxes. The orchestra serves as an equal partner with the voice; the interludes are dramatically important, binding one scene to another and unifying the whole opera. There are some fine choral scenes (particularly in the last act), and some of the aria melodies are related to the folksong idiom, though the solo lines for the most part are declamatory and interwoven with the orchestral texture.

The early wholesale condemnation of Lady Macbeth gave way to a more discriminating evaluation by later Soviet critics, especially since a marked change in Shostakovich’s style was clearly apparent in his Fifth Symphony (1937)—a change that mirrored the transition from the revolutionary and experimental period in Soviet music to a period of stricter control under party directives. Similar but less acute crises of policy occurred afterward, notably in 1948, when criticism of Velikaya druzhba (The Great Friendship, 1942), an opera by Vano Muradeli (1908–70), caused it to be withdrawn.7 This criticism subsequently initiated an official decree warning against “formalism” and “antipopular” tendencies in Soviet music.8 Such decrees, however, did not deter Muradeli from writing for the theater; his Oktyabar (October, 1964) is a very patriotic work. Not only is it filled with folk and revolutionary songs, but it also features Lenin in one of the vocal roles.

Objections were made also to the historical opera Bogdan Khmel’nyts’ky by Kostyantyn Dan’kevych (1905–84), when it came out in 1951, but a new version two years later was more favorably received. A similar fate awaited Shostakovich’s reworking of Lady Macbeth. His revisions, however, were so extensive that, in essence, Shostakovich created a new opera, acknowledged not only by a change in title, Katerina Izmailova, but also by a new opus number. The new version toned down the explicit passages in both libretto and score; when the opera was given in Moscow and London in 1963, critical opinion of the musical revisions was generally favorable. More recently, opera houses have been staging the original version of Lady Macbeth, discovering it to be one of the most powerful works of the twentieth century. The success of its revivals, which began in the 1980s, will surely diminish the likelihood that Katerina Izmailova will remain in the standard repertoire.

The only other operatic work by Shostakovich, with the exception of his operetta Moskva, Cheryomushki (1959), is Igroki (The Gamblers); it was to have been a setting of Gorky’s play of the same title, “without any cuts or adaptations,” but it was never completed. Shostakovich abandoned the score in 1942, after composing music for about one-third of the play, and reused some of the thematic material in his Sonata for Viola and Piano (1975). Interest in the truncated operatic score was perhaps rekindled by performances of the Sonata, for in 1978 a concert version of the extant portion of The Gamblers and in 1990 a staged version of the same at the Moscow Chamber Theater were performed.

ANOTHER OUTSTANDING NAME among the composers of the Soviet Union is that of Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953).9 Neither his life nor his music can be called typical for a Soviet composer. From 1918 to 1932, he lived abroad, chiefly in Paris, but also in the United States. An early opera, Igrok (The Gambler) composed between 1915 and 1917, would have been staged upon its completion had not the Russian Revolution occurred that year. The opera, drawn from Dostoyevsky’s autobiographical novella, was first performed (in a revised version) at Brussels in 1929, and since that time it has enjoyed frequent revivals.10 Prokofiev wrote the libretto, freely adapting the original to suit his purposes. One such example occurs in a scene with Alexei, alone on stage, singing a monologue in which he repeatedly calls out the name of Pauline, the person whom he realizes is at the center of his life. The scene is meant to reveal the inner thoughts of Alexei to the audience, not to the other personages of the drama, and therefore his calls for Pauline are not expected to generate an answer. But Prokofiev decides not to observe this operatic convention, and before Alexei can exit at the conclusion of the monologue, Pauline enters, and as she does so, asks rather perfunctorily “who is calling my name?” The story of The Gambler is conveyed in a richly crafted declamatory style that responds to every nuance of the text, to every change in mood. The emotional intensity of the opera builds toward the scene in the casino, a masterfully designed finale that is enhanced by very effective writing for the orchestra.

Lyubov k term apelsinam (The Love for Three Oranges) was commissioned by the impresario of an opera company in Chicago, and therefore was accorded its premiere in that city in 1921. This opera has a merrily lunatic plot based on a fantastic tale by Gozzi well suited to Prokofiev’s sharp rhythmic style of this period and to his talents for humor and grotesquerie. Choruses, external to the action, intervene capriciously; the solo parts make a mosaic of detached phrases over sparse but colorful orchestration; the only extended tunes are the well-known march and scherzo.

Prokofiev’s next opera was Ognenny angel (The Fiery Angel, composed in 1919–27; staged at Venice, 1955). Another fantastic libretto—this time a tragedy, laid in Germany of the sixteenth century, full of superstition, evil magic, ecstatic visions, hallucination, and horror—gave occasion for a complex but theatrically effective score, with arioso vocal lines over rather heavy orchestral accompaniment and some impressive choral scenes forming the climax of the last act. The Fiery Angel, being sadly deficient in optimistic proletarian spirit, was initially welcomed only in “the decadent West.”

In 1932 Prokofiev returned to Russia and began the long and difficult process of adapting his earlier pungent, ironic, often dissonant style to the requirements of his own country. He busied himself with ballets and other semi-dramatic compositions (including Lieutenant Kije; the “symphonic tale” Peter and the Wolf; and the cantata Alexander Nevsky) and finally with a new opera Semyon Kotko (1940) based on scenes from the life of a hero of the revolution of 1917. Here the composer’s typical declamatory prose style was relieved by some tuneful episodes, but both libretto (written, as usual, by Prokofiev himself) and music were criticized. Semyon Kotko was soon withdrawn, but it was revived in both a concert performance in 1957 and on the stage at Leningrad in 1960. Another opera on a contemporary subject Povest o nastoyashchem cheloveke (The Story of a Real Man) was withdrawn after a private performance in 1948; its first public performance took place at Moscow in 1960.

More successful was the comic opera Obruchenie v monastyre (The Betrothal in a Monastery), performed at Leningrad in 1946 and revived at Moscow in 1959. The libretto, adapted from Richard Sheridan’s eighteenth-century play The Duenna (by which name the opera is usually known abroad), gave Prokofiev ample scope for comedy and satire as well as for lyrical expression, providing likewise “an opportunity to introduce many formal vocal numbers—serenades, ariettas, duets, quartets and large ensembles—without interrupting the action.”11 These “formal vocal numbers” are scattered throughout the score; many of them alternate kaleidoscopically with fragments of dialogue in short, tuneful phrases or strict recitative, all held together by a continuous pulsatile accompaniment with countermelodies and mildly dissonant harmonies. The whole spirit and structure of the work, as well as the plot and characters, make it a charming modern descendant of the classical opera buffa.

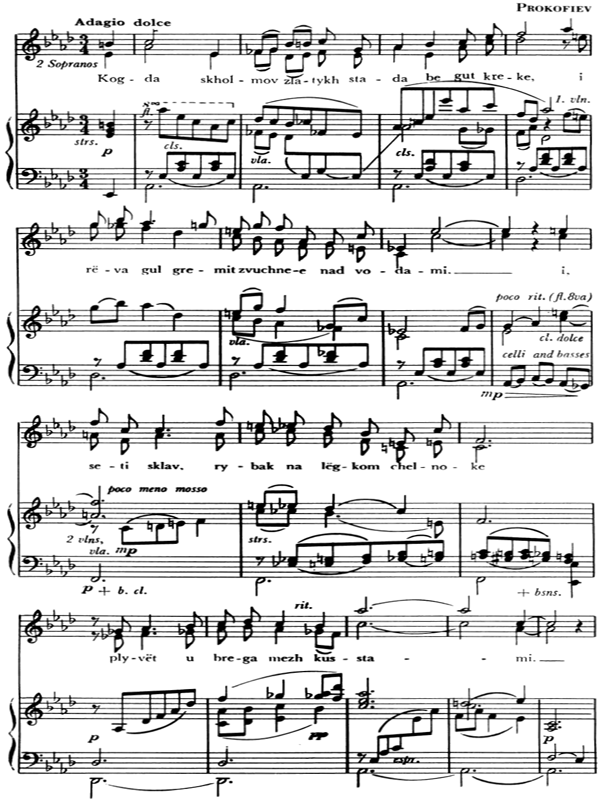

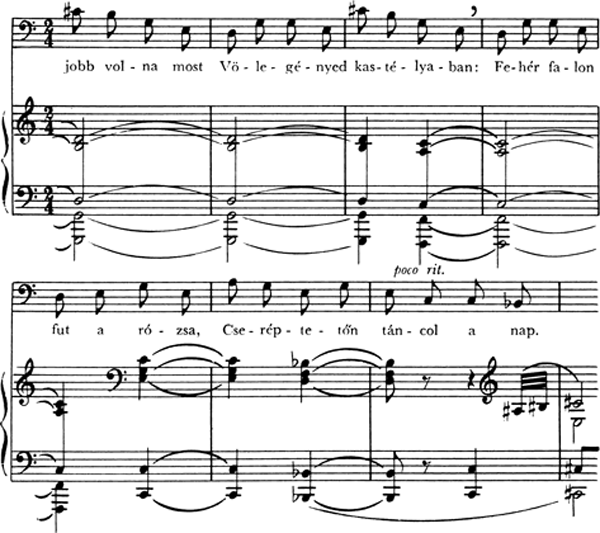

Prokofiev’s operatic masterpiece Voyruz i mir (War and Peace) premiered in 1955 at Leningrad. Based on Tolstoy’s novel and composed largely under the patriotic emotions of the war years, this is a historical grand opera of heroic proportions, consisting in its final form of thirteen scenes and a choral epigraph (that is sometimes performed at the beginning of the opera and at other times directly before the war scenes).12 The epic range of incidents and emotions is matched by music of corresponding variety and convincing dramatic power. As in his previous operas, Prokofiev makes some use of recurrent themes as a unifying device, and in the vocal writing he maintains a balance between flexible declamation and lyrical closed forms, both solo and ensemble (example 27.1). Choruses contribute to the grandeur of the whole, though not so conspicuously as to overshadow the individual characters. The score is particularly rich in expressive (not sentimental) melodies, and the distinctly national character of the melodic writing is unmistakable; the harmonic style is tonal, prevailingly diatonic and consonant, but with a quality of originality that reminds one of Musorgsky. More than any of his other works for the theater, War and Peace places Prokofiev in the great tradition of Russian opera: profoundly national in inspiration and musical style but also profoundly human and therefore transcending national limitations.

At St. Petersburg, a singularly different opera, a “cubo-futurist opera,” came to the stage in 1913. Pobeda nad solicem (Victory Over the Sun) is unusual in the sense that it intentionally accentuates visual rather than dramatic or musical impulses. It evolved from a collaboration of Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexej Kruchenyh, “futurist” writers; Kasimir Malevich, a Cubist artist; and Mikhail Matiushin, a musician who was also a painter and an art historian.13 The libretto for Victory Over the Sun is written in a “language” that replaces conventional word structure with pure “sounds” to evoke verbal images. While the language may at times be incomprehensible, the theme of the libretto is unmistakably clear: the Sun, symbol of the present, must be captured so that one may experience the future—even a sunless future, which would be preferable to the boring present. This synthesis of art forms produces a unique staged phenomenon to which audiences then and in the recent past have responded with a degree of enthusiasm that is best described as wild and exuberant.14

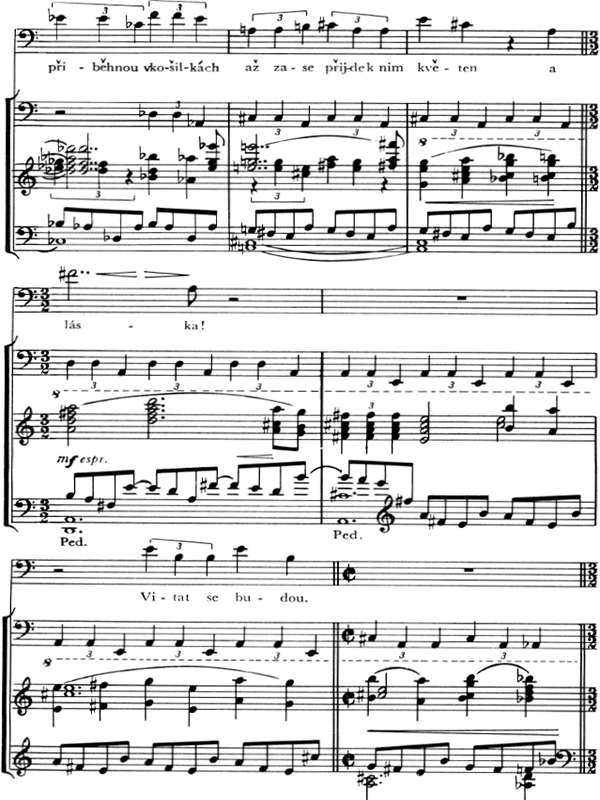

EXAMPLE 27.1 War and Peace, Act I, scene i

AMONG THE MANY non-Russian national operas by Soviet composers that have been performed since 1930 may be mentioned Shah-Senem (1927; revised, 1934) by Reyngol’d Glier (Reinhold Glière, 1875–1956), who was invited to the Republic of Azerbaijan in 1923 for the purpose of helping to develop its musical institutions. During his residence there, Glier composed Shah-Senem, based on an Azerbaijan legend; the score combines native folk elements with an expressive Russian Romantic style. In 1939 Sergey Vasilenko (1872–1956) was in Tashkent and was much taken with colors and rhythms derived from Uzbek music. This inspired him to compose Buran (1939), the first Uzbek opera; the score draws heavily upon regional elements. Operas in the Tatar language were composed by Nazib Zhiganov (1911–88); they include the historical-legendary Altïnohach (Golden Haired, 1941), winner of the USSR State Prize in 1948, and Dzhalil (1957), based upon the life of the Tatar poet Masa Dzhalil and events related to World War II. Although Zhiganov makes considerable use of folk elements, his operas are firmly anchored in the tradition of classical Russian opera.

FOLLOWING THE ESTABLISHMENT of the new Ukrainian Republic in 1917, theaters there not only presented revivals, but also encouraged the creation and staging of new operas. Two of the leading composers of this era, Borys Lyatoshyns’ky (1895–1968) and Yuly Meytus (1903–97), designed their operas in the “grand manner.” Zolotyy obruch, also known as Berkuty (The Golden Ring, 1930; revised, 1970) is considered to be Lyatoshyns’ky’s masterpiece. This four-act music drama (later revised into three acts), is notable for its “modern” harmonic language and its expressionistic stance, strongly suggestive of Berg’s Wozzeck. The story tells of a young man who risks his life to rescue the daughter of the leader of a rival group, the Tatar horde, only to tragically die in a flood when his own group removes a river barrier to prevent the Tatars from advancing on the village.

For his opera Shchors (1938), Lyatoshyns’ky turned to a historical figure; the story tells of the exploits of Mykola Shchors, a Soviet partisan leader during the 1917 Ukrainian Revolution.15 Both works were produced before Ukrainian composers were required to observe in the creation of their artistic works the Soviet Union’s policy of “socialist realism,” a policy that prevailed until the 1970s.16 Many of Meytus’s works, however, were written during the period of Soviet censorship; therefore it is not surprising to find his operas embracing revolutionary and peasant themes, with the revolutionary in Moloda hvardiya (The Young Guard, 1947), his first operatic success, and the peasant in Ukradene shchastya (Stolen Happiness, 1960), an opera that still holds its place in the Ukrainian repertoire.

A younger generation of composers is represented by Yevhen Stankovych (b. 1942) and Volodyymr Zubyts’ky (b. 1953). In the mid-1970s Stankovych wrote a folk opera Tsvit paporoti (The Fern’s Bloom) that was withdrawn after only two rehearsals, on orders from those who were charged with enforcing a countrywide campaign against nationalism expressed in the arts. Although the opera was denied a public performance, the score nevertheless greatly influenced Zubyts’ky’s writing of Chumats’ky shlyakh (The Galaxy, 1983), which is based on Ukranian legends.

EACH OF THE BALTIC STATES—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—also created its own respective national operatic repertoire, but not until after World War I. The opening of the Latvian Soviet Opera in 1913 and the organization of an opera company at Riga in 1919 assured composers in Latvia of an opportunity to have their operas performed. Among the more successful composers was Alfrēds Kalniņš (1879–1951), with Banuta (1920; revised, 1968), the first full-length Latvian opera, and Salineki (The Islanders, 1926), a historical opera that focuses on the self-sacrifice of persons who, in the cause of freedom, were willing to struggle against their oppressors. From 1927 until 1933 Kalniņš resided in New York; upon his return to Latvia he revised The Islanders, giving the opera a new title—Dzimtenes atmoda (The Nation’s Awakening, 1933). Other Latvian composers include Jāzeps Mediņš (1877–1947), with Vaidelote (The Priestess, 1927);Jānis Mediņš (1890–1966), with Uguns un Nakts (Fire and Night, 1921); and Jānis Kalniņš (b. 1904), with Hamlets (1936) and Ugunī (In the Fire, 1937), both composed in a conspicuously anti-Romantic style.17

In Lithuania, Mikas Petrauskas (1873–1937) took the first step toward the creation of a national opera when he wrote the incidental music for the play Birutė, staged at Vilnius in 1906. Petrauskas, known primarily for his operettas and Lithuanian revolutionary songs, was forced to leave his homeland for several years because of political unrest.18 During this period of exile, he visited the United States, where his opera Eglėžalčių karalienė (Egle, Queen of the Snakes) had its premiere in 1920. Some nineteen years later, Egle was accorded its first Lithuanian performance at the opera house in Kraunas, where a resident opera company had been established toward the end of 1920. Other Lithuanian operas include those composed by Jurgis Karnavičius (1884–1941), whose Gražina (1933) is considered the first national opera of Lithuania, and by Antanas Račiūnas (1905–41), whose Marytė (1953) is based on the life of Marytė Melnikaitė, a hero of the Soviet Union. Račiūnas also wrote Trys talismanai (The Three Talismans, 1936), a work in six scenes that makes use of traditional folk material, such as the song-and-dance form called the sutartinės. So successful were the initial productions of Marytė and The Three Talismans that these two operas soon took their rightful places in the regular national repertoire. Beginning in the 1950s, new Lithuanian operas, numbering more than forty, had their premieres at theaters in one of three cities—Vilnius, Kaunas, or Klaipėda. These forty operas have in common one characteristic: they adhere to the strict guidelines of “socialist realism.”

From 1940 to 1991, Estonians were ruled by a foreign power, the Soviets, but from 1918 until 1940 and again from 1991 to the present, they were, and continue to be, accorded their independence. Arthur Lemba (1885–1963), one of Estonia’s most important composers, is remembered for two operas: Armastus ja Surm (Love and Death, 1933) and Elga (1934). His younger colleague Eugen Kapp (b. 1908), was made the People’s Artist of the USSR in 1986 and was twice awarded the Stalin Prize for two of his operas, Tasuleegid (Flame of Vengeance, 1945) and Vabaduse Laulik (Bard of Freedom, 1950). His favor with the Soviet authorities was dependent upon his adherence to the political guidelines that applied to artistic creations, namely, that the music must be accessible to the general populace.

ARMENIA

Composers of opera in Armenia during the first half of the twentieth century include Armen Tigran Tigranyan (1878–1950), Alexander Afanasil Spendiaryan (1871–1928), and Haro Step’anyan (1897–1966).19 Tigranyan’s first opera, Anush, firmly established an Armenian national opera style. Its folklike musical material intensifies the tragic story of Anush and Saro, victims of social injustice and prejudice. A private performance of the opera took place in 1912, but the first public production of Anush came in 1935 at the Erevan State Opera Theater, after which the opera became an immediate success. From the late 1930s to the present day, Anush has held a prominent place in the performance repertoire of opera houses in Erevan (capital of Armenia), Moscow, and St. Petersburg.20 The pride and spirit of Armenian life is also present in David-Bek, an opera composed by Tigranyan at the end of his career and performed at Moscow in 1950. The libretto presents an eighteenth-century conflict between Armenians and Persians. Folksongs and dances associated with the warring factions represented in the opera bring to this heroic subject an expression of national realism. Twenty years earlier, Spendiaryan had used this same eighteenth-century Armenian-Persian conflict for his opera Almast (Moscow, 1930). Native folksong material played an important role in the five operas composed by Step’anyan. Of this number K’adj Nazar (Brave Nazar, 1935) and Lusabatsin (At Dawn, 1938) were particularly successful.

Central and Eastern Europe

CZECHOSLOVAKIA

Leoš Janáček (1854–1928), the leading composer in Czechoslovakia in the first quarter of the twentieth century, may be called a nationalist in the sense that all his operas were written to texts in his own language and his melodic idiom was one that grew organically out of the rhythms and inflections of national speech and folksong. But his style, particularly in the late works, was so individual and his genius for dramatic characterization so exceptional as to make him a figure of more than national importance. The first opera Janáček composed was Šárka, a Czech mythological opera set to a libretto by Julius Zeyer; it was completed c. 1888 but not performed until 1925. Also in 1888 Janáček began collecting folksongs in his native Lašsko; the fruits of this research make their appearance in his second opera, Počátek románu (The Beginning of a Romance), composed in 1891 but not performed until 1894 in Brno. In this one-act comedy, a so-called village opera, the proportion of folksongs and dance tunes (that Janáček had previously orchestrated) far outweigh the newly composed material.

His first major opera, Jenůfa, is a tragedy; it was produced at Brno in 1904 but ignored elsewhere until after a lavish production at Prague in 1916. Its central themes of love, death, and regeneration are common to Janáček’s final four tragic operas, all written after the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. In Jenůfa, the sufferings of the heroine, falsely accused of murdering her illegitimate child, awaken in the three principal characters an awareness of a higher level of moral integrity, one that transcends the conventions of village life and rituals. Jenůfa stands apart from Janáček’s later works because of its structural dependence upon set-numbers, including ensembles and choruses. At the same time, along with its expansive melodies of a more conventional romantic sort, there are already passages showing distinctive shapes and concise rhythms arising out of speech intonation.

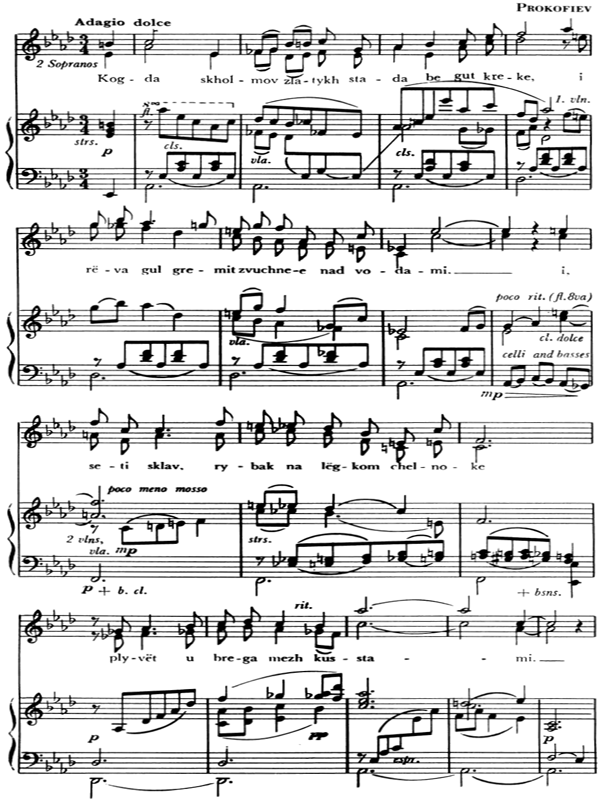

Greater concentration of both drama and music is found in the beautifully poetic Kát’a Kabanová (1921)—a work equally remarkable for sensitive characterizations, fine orchestral colorings, and an indescribable poignancy of expression in the melodic outlines (see example 27.2)—one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century opera. It is in this opera that Janáček begins to develop his own unique interpretation of operatic conventions. The conciseness of his libretto allows the action to proceed at breathless speed. Monologues become more numerous; recurring motifs add an important orchestral dimension; the chorus, no longer needed as a visible protagonist, assumes an offstage location and functions as a collective symbolic force with its interjections of wordless and mysterious sounds.

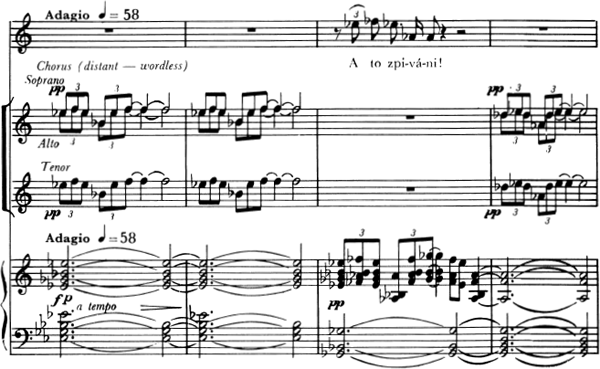

The circularity of life forms the key philosophical point of Janáček’s next opera, Příhodylíšky Bystroušky (The Cunning Little Vixen, 1924). Tender and strange, a blend of humor and pity, this unusual opera requires a cast of talking animals and humans. Janáček based his tale on Rudolf Téšnohlídek’s novel Vixen Sharp-Ears (1920), which sets forth a nineteenth-century Moravian folktale about the adventures of a fox and a forester. In the opera, the forester comes to an awareness of the sadness of old age tempered by the miracle of nature’s renewal in the forest. “Here in these woods,” sings Janáček’s Forester (example 27.3), “life renews itself, and the nightingales return with each returning Spring to find their nests, and Love … always the same: where then was parting, now is meeting.”21 The Cunning Little Vixen is a work that may be regarded as complementary to Kát’a Kabanová but is even more original in style, despite some impressionistic influences in the harmony and orchestration. Of particular interest are the ballets (for the Flies, the Blue Dragonfly, the Cricket, the Grasshopper, and the Mosquito) that serve as connecting threads for the episodic libretto.

Věc Makropulos (The Makropulos Affair, 1926), based on Karel Čapek’s play, shows Janáček on the way to the final stage of his style, reached in the Glagolitic Mass of 1927 and the opera Z mrtvého domu (From the House of the Dead), composed in 1928 and first performed in 1930. In The Makropulos Affair an eternally beautiful woman returns to Vienna seeking the formula for a longevity potion, which has preserved her for more than three hundred years. Her mysterious sensuality is signaled orchestrally by the introduction of a viola d’amore, an instrument Janáček used with similar connotations in the first version of Osud (1903–5) and in Kát’a Kabanová.22 By contrast, her perversion of natural life evokes a musical response that is harsh, dissonant, angular—a cruelness thrust upon the audience in the opening orchestral prelude. From the House of the Dead has no plot, properly speaking; its scenes are taken from Dostoyevsky’s memoirs of his prison life in Siberia. Except for a few measures in Act II sung by the old prostitute, the opera is scored for male voices, collectively assembled as a chorus from which individual soloists step forward to relate their brutal experiences. Only once does a fleeting moment of hope penetrate the bleakness of the penal camp—the moment when a wounded eagle is released and the prisoners sing of freedom. Janáček’s music for From the House of the Dead is intensely concentrated, stark, primitive, violent, with rough harmonies and raw orchestral colors—a grim finale for a composer whose four greatest operas were all written after the age of sixty-five.

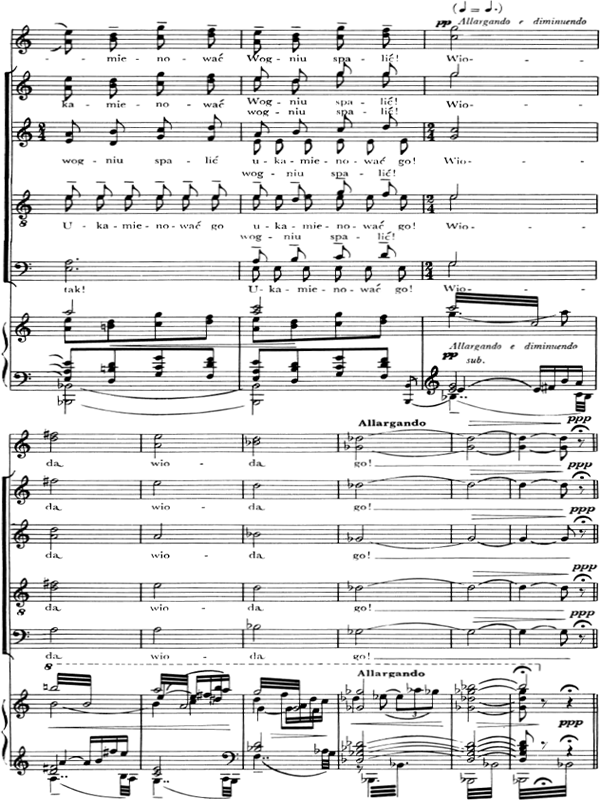

EXAMPLE 27.2 Kát’a Kabanová, Act III

Kát’a Kabanová—Janáček. Piano-vocal score, Universal Ed., plate no. U.E. 7103, 143–45. With kind permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition.

JANÁCEK TAUGHT COMPOSITION at the Conservatory of Music in Brno, and among the students who studied with him from 1920 to 1922 was Pavel Haas (1899–1944). In the course of his brief life, Haas distinguished himself with a number of works, not the least of them his tragic-comic opera Šarlatán (The Charlatan, 1938).23 This opera, in three acts, is set to a libretto by the composer, which he fashioned from a novel by Josef Winckler. The score is written in an accessible and melodic style and incorporates elements related to Moravian folksong, Jewish chant, and jazz rhythms.24 A revival of The Charlatan at the 1998 Wexford Festival in England has drawn attention to the merits of this opera and its composer.

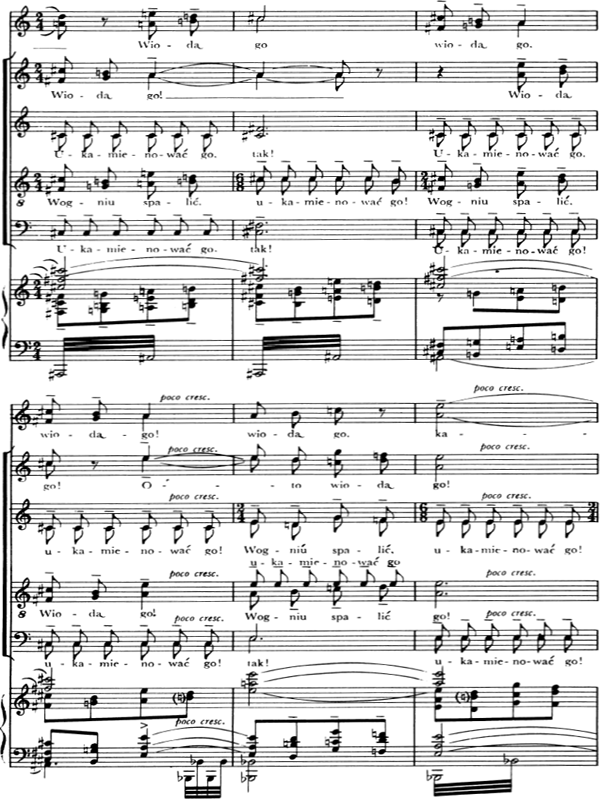

EXAMPLE 27.3 The Cunning Little Vixen, Act III

Das schlaue Füchslein—Janáček. ©1924 by Universal Edition. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors Corporation, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition.

Other important Czech operas, many of them incorporating folkloristic elements, include Vina (The Sin, 1922) by Otakar Zich (1879–1934); Smrt kmotřička (Godmother’s Death, 1933) by Rudolf Karel (1880–1945); the three-act comedy Bílý pán, aneb Těžko se dnes duchům straší (The Gentleman in White, or No Haunts Left for Ghosts, 1929; revised 1931) by Jaroslav Křička (1882–1969), which is after Oscar Wilde’s The Canterville Ghost; and Krútňava (The Whirlpool, 1949) by Eugen Suchoň (1908–93). Of these, none was more popular at home or abroad than The Whirlpool, an opera that in its depiction of rural village life invites comparison with Jenůfa.25 The score includes spoken dialogue along with recitatives and arias; the chorus has a very important role, often functioning as the voice of the community. Ample opportunity to introduce folksongs, dance, and colorful costumes are provided by such scenes as the wedding celebration. The overarching structure to the organization of the opera’s six scenes is similar to sonata form, with scene iv acting as the pivotal development section. Suchoň also had success with his epic drama Svätopluk (1960). This opera is based on historical events surrounding the life of the ninth-century King Svätopluk who ruled over the Moravian Empire. Once again, the composer has an opportunity to introduce folk music, along with other types of music such as Byzantine chant.

Two operas by Alois Hába (1893–1973)—Matka (The Mother, 1931) and Nová zemé (The New Land, composed 1934–36, but never performed)–are of particular interest, for in the score of the former the composer used quarter-tones and in that of the latter he used sixth-tones. Hába’s interest in quarter-and sixth-tones led to the founding of a department of microtonal music at Prague Conservatory in 1924. His music also prompted the construction of instruments that could execute the unusual requirements of the microtones.26 His brother, Karel Hába (1898–1972), wrote four operas between 1934 and 1960. Among them was a children’s opera designed for radio broadcast and Jánošík (1934), a work drawn from historic folktales about Juro Jánošík the Slovakian “Robin Hood,” who lived from 1688 to 1713. A Czech composer who ran his own experimental theater in Prague was Emil Frantisek Burian (1904–59). Of his six operas, the most important is Maryša (1940), a tragedy centering on a peasant girl who is forced to marry against her will.

Comic operas of a robust and popular character were also appearing around this time in Czechoslovakia. Švanda dudák (Švanda the Bagpiper) by Jaromír Weinberger (1896–1967), first performed at Prague in 1927, is doubtless the most widely known of these. Bohuslav Martinů (1890–1959), a native of Czechoslovakia who from 1923 lived in Paris and later in the United States, has been heard mainly in symphonic and chamber compositions, but he also wrote twelve operas, both comic and serious. Unfortunately, all remain little known.27 They include Veselohra na mostě (Comedy on the Bridge, 1937); Julietta (1938), set to Martinů’s adaptation, in Czech, of La Clé des songes, a French play by Georges Neveux; What Men Live By (1953), with a libretto in English by Martinů; and Řecké pašíje (Greek Passion, 1961).28 The last named is Martinů’s final opera, a large-scale tragedy based upon Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel Christ Recrucified. It is the story of humble Greek peasants who are selected to reenact the drama of Christ’s Passion; in preparation for so doing, they begin to assume in real life the traits and trials of the biblical characters they are called upon to portray. Local color is supplied by the singing of Greek folksongs and Orthodox chant. The opera’s four acts are divided into tableaux, with the chorus assuming a commanding position in the concluding scene.

POLAND

The two principal Polish opera composers of the early twentieth century were Ludomir Rózycki (1883–1953) and Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937).29 Rózycki, though regarded in Poland as a nationalist composer, had absorbed Western influences from Germany. His works include Erosa i Psyche (1917), the comic opera Casanova (1923), and Beatrix Cenci (1927). Szymanowski, the leading Polish composer of this period, worked primarily in symphonic and choral forms but he did write two operas: Hagith (composed 1912–13; performed 1922) and Król Roger (King Roger, 1926). Hagith was influenced in its subject matter and construction by Strauss’s Elektra and in its harmony largely by the music of Ravel. It is based on legends of King David as well as on the biblical account of the king’s life. King David has reached his advanced years and Hagith is called upon to sacrifice herself as a means of restoring the king’s vitality. Hagith refuses the command, for she is in love with the young prince, and is thereby stoned to death.

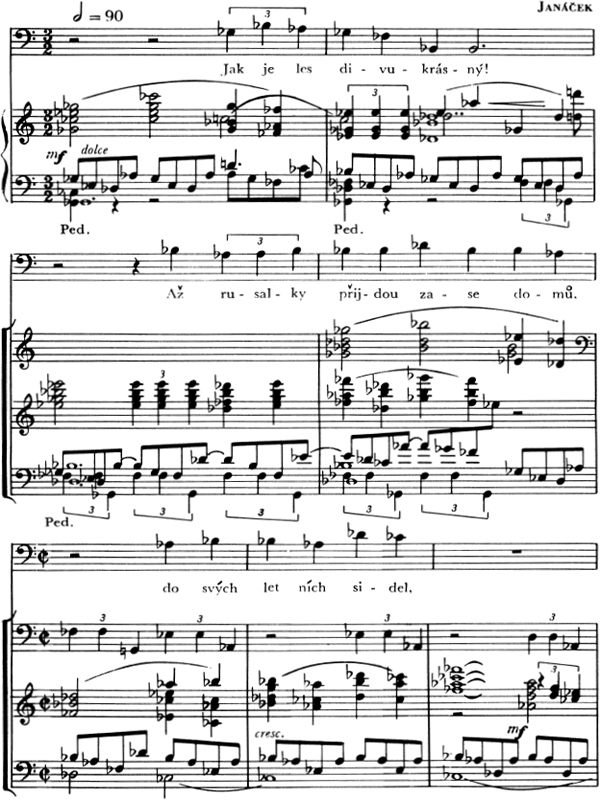

King Roger is considered to be Szymanowski’s masterpiece. The opera is a monumental dramatic work in three acts. The libretto, somewhat similar to Schreker’s Der ferne Klang, tells of Dionysus, disguised as a young shepherd, who arrives at the medieval court of King Roger (a Christian) in Sicily, and brings with him a message about the mysteries of divine love as expressed in pagan religion. Many members of the court succumb to the shepherd’s message. Even the king initially believes the message and begins to follow the shepherd as a pilgrim, but eventually he resists the temptation. He alone is able to withstand the Dionysian forces within him. Szymanowski did not set the libretto as written; he ends the opera with the king succumbing to the shepherd’s message. The music is harmonically rich in a neo-impressionistic idiom, with national influences in the melody; the solo lines range freely from declamatory phrases to ample melodic arches. The choral writing is particularly effective; some of the choral sonorities are derived from the Russian church style, with full texture, doubling of the parts, and parallel movement of the voices (example 27.4). In Act II the music reflects the Dionysian realm, with oriental motifs introduced in the ballets.30

The leading Polish opera composer of the mid-twentieth century was Tadeusz Szeligowsky (1896–1963), whose Bunt zaków (The Scholars’ Revolt) was produced first at Warsaw in 1951 and shortly thereafter at other Polish cities and also at Moscow.31 The plot of The Revolt is based on an incident at the University of Cracow in 1549: the “Zaks”—students of peasant birth who received their education in return for performing menial duties—rebelled because of ill treatment and left the university and the town as a group. A love story and some comic episodes have been added to make up the libretto, but the main emphasis is on the stirring choral scenes. Szeligowsky’s music, though harmonically conservative, is very well adapted to the requirements of the theater. Many of the tunes and rhythms have a definite national folk character; in keeping with the historical background are some stylized or literal references to Polish poetry and music of the sixteenth century.

THE SECOND HALF of the twentieth century is represented, in part, by the works of Krzystof Penderecki (b. 1933). Although his compositional style was aligned with the Polish avant-garde of the 1960s, his music found favor at home and abroad, especially with his St. Luke’s Passion. It was also in the 1960s that he turned his attention to the theater. His first opera, Najdzielniejszy z rycerzy (The Most Valiant Knight, 1965), written for children, was followed by four major works for the stage: The Devils of Loudon (1969); Paradise Lost (1978), a sacra rappresentazione based on John Milton’s epic poem;32 Die schwarze Maske (1986); and Ubu Rex (1991), which is a pastiche of various musical styles.

In Die schwarze Maske, Penderecki melds his former experimental style with a more neo-romantic one, and even incorporates seventeenth-century music into the score (chorales and dance music) to re-create the period in which the opera is cast, namely, Carnival time in a Silesian town during the 1660s after the close of the Thirty Years War. The libretto is based upon a one-act play of the same title by Gerhard Hauptmann and centers on a secret that the burgomaster’s young wife wants to keep from her husband, whom she recently married in Holland. The story underscores Penderecki’s penchant for librettos that recount tales of social injustices for which no resolutions can be found. The forces required for a production of this opera are formidable: fourteen solo roles, a very large chorus, a large orchestra (augmented with celesta, organ, and a battery of percussion instruments) located in the pit, and a Baroque-styled ensemble positioned on stage. In all his operas, Penderecki strives for dramatic immediacy, with music that embraces the verismo tradition.

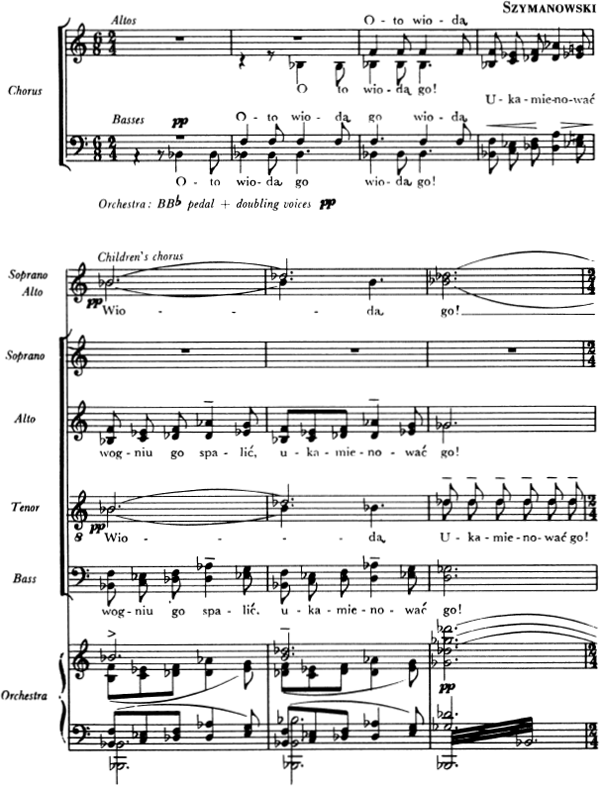

EXAMPLE 27.4 King Roger, Act I

Król Roger—Szymanowski. © 1925, 1953 by Universal-Edition. © renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission of European American Music Distributors LLC, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition.

A younger contemporary of Penderecki is Marta Ptaszynska, who has had considerable success with her opera Oscar of Alva (1972). Although this opera was originally designed for, and produced via, television, it has played equally well in an opera house before a live audience, as confirmed by a production at the Salzburg Festival in 1989.

HUNGARY

The most famous opera to come out of Hungary in the early twentieth century was A Kékszakállú herceg vára (Bluebeard’s Castle) by Béla Bartók (1881–1945).33 It was composed in 1911 and first performed at Budapest in 1918. In this score, various threads of Bartók’s musical vocabulary—the Hungarian and the traditional European—are woven together to form a seamless whole, creating “the first genuinely Hungarian and at the same time modern opera.”34 Béla Balázs’s libretto was inspired by Friedrich Hebbel’s theories of tragedy, by Charles Perrault’s original fairy tale, and by Maurice Maeterlinck’s own version of the ancient tale, Ariane et Barbe-Bleue, published in 1910 as a “mystery play.”The opera has only two characters (Bluebeard and his fourth wife, Judith) and contains hardly any external action; the inner, symbolic drama proceeds with the opening, one after another, of the seven doors that lead into the hall of Bluebeard’s castle. Each opening reveals an aspect of Bluebeard’s past, such as his riches and his power to destroy.35 Bartók’s music, like Debussy’s for Pelléas, seems a perfect and inimitable embodiment of the mysterious text. The music flows unbrokenly throughout the single act, its continuity emphasized by the recurrence of “pivot” motifs and themes. The orchestral color and harmony, impressionistic in essence but stamped everywhere with Bartók’s individuality, supports a vocal line consisting for the most part of irregular declamatory phrases whose melodic and rhythmic outlines derive from Hungarian folksong (example 27.5).

Equally imbued with Hungarian national feeling, though far less radical in musical idiom than Bluebeard, are the stage works of Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967): Háry János (1926), on the adventures of a comic character from national folklore; Székely fonó (The Spinning Room, 1932), a ballad opera that was revised from the original version of 1924; and Czinka Panna, composed for a national centennial celebration and produced at Budapest in 1948.36 Háry János and Czinka Panna are composed according to the Singspiel tradition; spoken dialogue is combined with songs and choruses either borrowed from or composed in the style of folk music. In The Spinning Room Kodály dispenses with the dialogue and uses mime artists to convey the essence of the plot.

A more international Romantic style is characteristic of the music by the noted pianist-composer Ernő Dohnányi (1877–1960), as is evident in his three-act opera A Vajda tornya (The Vaivode’s Tower), produced at Budapest in 1922. Dohnányi is perhaps best remembered for Der Tenor (Budapest, 1929), considered to be one of the finest comic operas written in the first half of the twentieth century.37 The libretto, based on Carl Sternheim’s Bürger Schippel, concerns a German civic vocal quartet that needs to find an immediate replacement for the recently deceased tenor of the ensemble. The only person available is a drunken flautist who frequents a nearby tavern. Comic situations develop when the flautist falls in love with the daughter of one of the burghers in the quartet and wants to marry above his station in society.

A very important and highly regarded composer of the second half of the twentieth century is György Ligeti (b. 1923), whose international reputation rests not only on his symphonic and chamber music but also on his Grand Macabre (1978; revised, 1997), which is representative of the avant-garde theater of the 1960s.38 Ligeti follows in the footsteps of a group of composers who have concerned themselves with the writing of the ultimate anti-opera. In Ligeti’s case, he describes his Grand Macabre as an “anti-anti-opera,” for it brings to the stage an apocalypse that, as it turns out, is not the ending that the audience was anticipating. Le Grand Macabre is based on a farce written by Michel de Ghesderode in 1934 and draws additional ideas from the paintings of Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Nekrotzar, the “Grand Macabre,” comes to Brueghelland to tell the inhabitants that the world is coming to an end. Brueghelland, it should be explained, is a kingdom of peasants, the very same kind of kingdom depicted by Brueghel. The kingdom is ruled by a young boy; his advisors are two rival politicians, the Black and White Ministers, who appear as larger-than-life puppets on stage. As the inhabitants of Brueghelland await the Day of Judgment, the Grand Macabre spends time interacting with several of them—the royal astrologer, two young lovers, and a drunken peasant. At the stroke of midnight, the world ends, but the inhabitants have not been annihilated as predicted. While they quickly adapt to their new post-Judgment Day existence, they notice that, quite inexplicably, the only person to disappear is the Grand Macabre himself: Death, not Life, has been annihilated. While the opera does not deny that Death is inevitable, it does emphasize that “‘till then, live merrily.”

EXAMPLE 27.5 Bluebeard’s Castle

Herzog Blaubarts Burg—Bartók. © and 1948 renewal assigned to Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Although Ligeti’s opera was originally set to a libretto written in German, Le Grand Macabre was first presented in Swedish, a translation having been made for the premiere performance that took place at Stockholm. Subsequent productions during the 1980s in France and Italy were sung in English, but a 1987 production at Vienna may have been sung in German. For the 1997 Salzburg Festival production, Ligeti made extensive revisions of the score, and presumably it is this English-language version that will continue to be used for future productions.

ROMANIA, CROATIA, AND SERBIA

A significant development of national opera in Romania came within the period bounded by the two world wars. Especially notable among the numerous composers who contributed to the indigenous repertoire during this era was Georges Enescu (1881–1955). He would seem to be a most unlikely composer to be singled out for his role in developing a Romanian repertoire, for he contributed but one opera, Oedipe (1936), and that opera had its premiere not in Bucharest but at the Opéra in Paris. Although Oedipe was initially well received by the Parisians, the opera remained in the repertoire of that organization for only a year. After that, nothing more was heard of this work until the 1950s, when a French radio broadcast of the work in 1955 and a fully staged production at Brussels in 1956 revived interest. Two years later the Bucharest Opera mounted its own production. The success of this venture caused Oedipe to become a standard part of the Romanian repertoire. The opera consists of a prologue and four acts, with the first two acts devoted to setting the scene for events that unfold in the next two acts. Act III is drawn principally from Oedipus tyrannus and Act IV from Oedipus at Colonus. Of interest is the melodic design of the vocal parts, which feature traditional Romanian folk material and the use of micro-intervals.

A contemporary of Enescu was Dimitrie Cuclin (1885–1978), who wrote his own librettos for the five operas that he completed. Unfortunately, the forces needed to mount his theatrical productions in the 1930s were too great and as a consequence not one of his operas ever came to the stage in his lifetime. Two years after the composer’s death, his Meleagridele (completed in 1930) was given a Romanian television production at Bucharest, providing audiences a taste of what his operas might have been like had they ever been accorded staged productions.

Three younger composers—Gheorghe Dumitrescu (1914–96), a prolific composer with at least seventeen operas to his credit, Paul Constantinescu (1909–63), and Aurel Stroe (b. 1932)—have also left their mark on the Romanian repertoire. Of particular interest is Dumitrescu’s “folklore music drama,” Răscoala (The Uprising, 1963), which draws on indigenous materials, and Constantinescu’s O noapte furtunoasă (A Stormy Night, 1934).39

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the city of Zagreb had become a focal point of a movement that strove for national cultural emancipation. The arts were the weapons of choice in this fight against the domination of foreign cultural ideals to which the Austrians and Hungarians had subjected the people of Croatia and Serbia. Not until the midpoint of the century, however, did the full force of this movement come to fruition. Among the first Croatian operas to reflect this new nationalistic thrust was Ljubav i zloba (Love and Malice, 1846) by Vatroslav Lisinskij (1819–54).40 Among other composers who helped to carry forth the campaign of cultural emancipation were Krešimir Baranović (1894–1975), with Striženo-Košeno (Shorn-Head, 1932), and Jukov Gotovac (1895–1982), with Morana (1930), Ero s onoga svijeta (Ero the Joker, 1935), and Dalmaro (1959). They turned their attention to incorporating folk elements into their compositional style, but with the advent of “social realism” in the late 1940s that aspect of operatic writing momentarily ceased. More recent operas that have contributed to the Croatian opera repertorie are Romeo i Julija (1955; revised, 1967) by Frešimir Fribec (1908–96), and Rikard III (1987) by Igor Kuljerić (b. 1938), one of the more-accomplished avant-garde Croatian composers. In Rikard III Kuljerić makes use of electronic taped music for musical transitions from one scene to the next.

The most important Serbian composer of the first half of the twentieth century was Petar Konjović (1883–1970). He twice served as director of the National Theater in Zagreb and also as director of theaters in several other cities of his homeland. In his operas, he focused on setting texts that were related to historical events and individuals, and his vocal writing was strongly influenced by the natural inflection of his native language. Folk elements are also very much in evidence in his scores, which are distinguished by exceptionally colorful orchestrations. His first successful opera was Knez od Zete (The Prince of Zeta, 1929); it tells of an unhappy love affair between a prince of Montenegro and the daughter of the doge of Venice, with the musical representation of the former colored by Montenegrin songs and of the latter by a lush Romantic musical style. Both Kostana (1931) and Seljaci (The Peasants, 1951) are set in Serbian villages and are replete with national songs and dances to reflect the rural lifestyle. Konjović’s last opera, Otadžbina (The Fatherland), was composed in 1960 but not performed until 1983 at Belgrade. The story is set in the fourteenth century at the time of the 1389 battle of Kosovo, during which a mother lost nine sons and a husband. The opera is cast in a form akin to an oratorio, with the polyphonic style of Serbian religious music very much in evidence in the choruses and ensembles. Given events in Serbia and Kosovo during the final decade of the twentieth century, when these two provinces were engaged in armed conflict, any revival of this particular opera would produce a very emotional evening in the theater, for undoubtedly many members of the audience would have experienced the death of loved ones not unlike that of the mother in the opera.

Greece and Turkey

Manolis Kalomiris (1883–1962) is credited with developing a truly Greek idiom for the National School’s operatic repertoire. Interestingly, a significant portion of the formative years of his musical career was spent not in Greece, but abroad, for after completing studies in Athens and Constantinople (now Istanbul), Kalomiris studied in Vienna and then spent four years (1906–10) at Kharkiv, where he taught piano and came in contact with Russian operas. Upon his return to Greece, he founded three separate conservatories and the National Opera Group—the latter, an experiment initiated in 1933, was short-lived.41 His five operas, produced between 1916 and 1962, reveal a penchant for melding Greek folksong with traditional musical elements. They also make use of leitmotifs and a type of “unending melody” usually associated with Wagnerian scores.42 Of particular interest is Kalomiris’s O protomastoras (The Master Builder, 1916), one of the first operas by a Greek on a Greek subject, and Konstantinos o Palaeologos, i Piran tin Poli (Constantine Palaeologue, or They Took the City), a festival opera on a historical subject—the last Byzantine emperor, who ruled from 1448 to 1453. Constantine Palaeologue was first performed in the theater of Herod Atticus at Athens in the summer of 1962.

Composers whose operas have been brought to the stage in the last third of the twentieth century include Mikis Theodorakis (b. 1925), with Medea (1991); Periklis Koukos (b. 1960), with O Conroy ke i kopies tou (Conroy’s Other Selves, 1990) and Oniro kalokerinis (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 1992); and Arghyris Kounadis (b. 1924), with The Return (composed in 1961, subsequently revised as O Gyrismos in 1974 and 1988, and finally staged in 1991), Der Bassgeige (1979), and Der Sandmann (1987). The Return is a modern interpretation of the Electra story in which the psychological moods of the characters are differentiated through a constant shifting between spoken and sung passages. Although Kounadis is considered one of the most important Greek composers of the second half of the past century, he usually had to look beyond the borders of his native land for performances of his works. In addition to operas, operettas have also been a popular feature of Greek theatrical productions, particularly those that poke fun at the lives of royal personages.

WITH THE ESTABLISHMENT of the Turkish republic in 1923, a wave of nationalism crept over the cultural landscape, so that by the next decade theaters in Ankara and Istanbul were able to present operatic works by native composers and librettists. Ahmed Adnan Saygun (1907–91) brought forth what is considered “the first true Turkish opera,” Özsoy (1934). His other operas include Taş bebek (1934), Kerem (1953), and Köroğlu (1973). Of these four, Köroğlu is his best-known opera; it is based on an old Turkish legend and incorporates elements of Turkish folk music, an area in which Saygun developed considerable expertise when he and Bartók researched this aspect of his native culture. Distinguished among a later generation of composers is Okan Demiriz (b. 1940), whose operas—Murat IV (1980), Karyağdi Hatun (1985), and Yusuf ile züleyha (Joseph and His Brethren, 1990)—have contributed significantly to the flowering of a national repertoire of Turkish opera.43

The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland

THE NETHERLANDS

Although the city of Amsterdam has been in the forefront of producing new operas by composers of other countries, the Netherlands has rarely brought forth operas by native composers. There are, of course, notable exceptions, such as Halewijn by Holland’s most successful composer of the first half of the twentieth century, Willem Pijper (1847–1947). Halewijn was given at Amsterdam in 1933, and is one of the few operas in the whole of Dutch musical literature. At the time of Pijper’s death, he left unfinished a second opera, Merlejn.44 At the very end of the twentieth century, another well-known Dutch composer Louis Andriessen (b. 1939) brought forth several works for the theater, including Writing to Vermeer (1999). This opera takes place in 1672 when Vermeer made one of his rare trips away from home, traveling from Delft to The Hague. Andriessen imagined that Vermeer had received letters from three important people in his life—his wife, his mother-in-law, and his model—during his brief absence from Delft and he designed an opera around eighteen such letters, six from each of these women. The entire opera is sung from the perspective of the three women, and in addition to this trio of sopranos, Andriessen has added two children and a vocal ensemble of six women. There are no male voices heard in this opera, for although Vermeer and his paintings are central to the opera, he does not reply to the letters and thus has no need to appear in the production. The libretto is in English, which has encouraged performances outside of Amsterdam.45 The staging of the opera involves scenes of old Dutch life projected on huge screens behind the singers. Andriessen’s score incorporates passages of electronic music; it also shows strong influences from Maurice Ravel and John Cage.

DENMARK

The director of the Royal Opera at the beginning of the twentieth century was Carl August Nielsen (1865–1931), perhaps the best-known of all Danish composers. Interestingly, he began his career as a violinist with the Royal Opera orchestra. The first of his two operas, Saul og David (1902), explores in its four acts the biblical account of events that unfold tragically between Saul and David. The score is strongly influenced by a Handelian-type of choral writing, as is evident in the several choruses sung by the Israelites. Nielsen’s orchestral writing is given ample opportunity to be heard in this work, especially in the prelude to Act II and in the dramatic depiction of a battle conveyed in the interlude that separates the two scenes of Act IV. Exceptionally fine solos also contribute to the overall grandeur of the opera. Nielsen’s Maskarade (1906) is an outstanding example of Danish comic opera and continues to hold its popularity with Danish audiences. The libretto, based on a comedy by Ludvig Holberg, embraces a nationalist theme. The score is modeled on Mozart’s comic operas and cleverly mimics their wit and fluent dialogue passages.

SWEDEN

Experiments in form as well as in subject matter and musical idiom were not the exclusive prerogative of composers working in Germany. Equally adventurous works had been appearing in other countries, especially since the 1940s. One of Sweden’s composers, Karl-Birger Blomdahl (1916–68), used electronic music in Aniara (1959) to create unearthly sounds for a drama about a spaceship out of control, falling endlessly into the interstellar depths. This setting by Blomdahl of Harry Martinson’s epic poem has become one of the most popular works ever staged at the Stockholm Opera. Its success has been attributed to the familiarity of the text and the variety of musical material, including a textless vocalise sung by the blind Poetess. Other stage works by Blomdahl include Herr von Hancken (1964) and his unfinished Sagan om den stora datan (The Tale of the Great Computer), on a book by Hanner Alfvén, in which he planned for electronic sound to take over from the live vocal and instrumental music used at the beginning of the score, paralleling the scenario in which computers render obsolete the roles of human beings.46

Lars Johann Werle (b. 1926), who studied composition with Blomdahl, reveals his aural-spatial experiments in Drömmen om Thérèse (Dreaming of Therese, 1964). This opera, which makes use of film and electronic music, was designed to be staged in the round, with the orchestra positioned behind the audience in various small groupings around the perimeter of the room.47Dreaming of Therese was followed by Resan (The Journey, 1969); Tintomara (1973), a three-act mystery play that has as its central theme the murder of Gustav III; and Medusan och djävulen (Medusa and the Devil, 1973). A number of Werle’s later compositions communicate his beliefs about the ills that infect the planet. His stand against environmental pollution and warfare, for example, is reflected in Animalen (Animal Congress, 1978), a political satire in the form of a fable on arms reduction, and in Lionardo (1988), which looks at inventions devised by Leonardo da Vinci and then reveals to the inventor the horrors he has unwittingly caused for future generations who have adopted his designs for making weapons of destruction.

Other composers of Werle’s generation who have had their operas successfully produced in Sweden include Sven-Erik Bäck with his chamber opera Tranfjädrarna (The Crane Feathers, 1957); Hilding Rosenberg, with Resa till Amerika (Journey to America, 1932) and Has med dubbel ingång (The House with Two Doors, 1970), after Calderón; and Ingvar Lidholm, with Holländarn (1967) and Ett drömspel (A Dream Play, 1991), designed for television.

Hans Gefors (b. 1952) and Jonas Forssell (b. 1957) are among a younger generation of composers who have had operatic productions in Sweden. Notably successful has been Forssell’s comic chamber opera Riket är ditt (The Kingdom Is Yours, 1991), for nine voices, mute actors, and a chamber ensemble; it concerns immigrants who, needing someone to shelter and care for them, ultimately take refuge in a convent. Gefors was acclaimed for his large-scale opera Christina (1986), which premiered at the Stockholm Opera and then two years later had a television broadcast.

FINLAND

In 1873, one year after the founding of the Finnish Theater (later known as the Finnish National Theater), an opera season was incorporated into the annual offerings of plays. Although this arrangement was short-lived, it paved the way for a more lasting enterprise, namely the founding of the new Domestic Opera Company in 1911 by the well-known composer and opera conductor Oskar Merikanto (1868–1924). In the opening decade of the twentieth century, composers began to build a repertoire of operas based upon Finnish legends, historical events, and folkloric themes. Such was the first opera in the Finnish language, Pohjan neiti (The Maid of the North), composed by Merikanto in 1898 and performed at Viipuri in 1908. His subsequent works, Elinan Surma (Elina’s Death, 1910) and Regina von Emmeritz (1920), were somewhat influenced by Italian verismo methods.

As important a milestone as The Maid of the North was, it was soon surpassed by Leevi Madetoja’s (1887–1947) Pohjalaisia (The Ostrobothians, 1925), considered to be the first “national” Finnish opera and one of the most successful Finnish operas of all time.48 The score includes a number of folksong tunes that were familiar to Finnish audiences. Madetoja was one of several prominent Finnish-speaking composers who had studied with Sibelius but were also strongly influenced by French composers whom they had encountered during sojourns in Paris. This influence is particularly perceptible in the impressionistic orchestration of The Ostrobothians. Madetoja’s second opera was Juha (1935), with a libretto by Aino Ackté; it is based on Juhani Aho’s 1911 novel of the same title, which had previously been set to music by Aarre Merikanto.49 Additional examples of a more distinctly national style, with folk melodies and recitative rhythms adapted to the Finnish language, are offered by Armas Launis (1884–1959) in Seitsemän veljestä (The Seven Brothers, 1913) and Kullervo (1917), and by Ilmari Krohn (1867–1960), a folksong scholar who produced the opera Tuhotulva (The Deluge) at Helsinki in 1928.

Aarre Merikanto (1893–1958) charted his musical career along a path that was diametrically opposite the Romanticism of his father, Oskar Merikanto. Aarre’s style of writing, especially in the 1920s, reflects the radical modernism that characterizes the music of some of his contemporaries, such as Väinö Raitio (1891–1945).50 Aarre Merikanto’s Juha (completed in 1922) was considered too modern for a production in Helsinki and was also faulted for its orchestration. Therefore the opera was not accorded any performances until after the composer’s death. Juha was first heard in a radio broadcast production late in 1958 and subsequently had its official stage premiere in 1963 at Lahti. Juha has since been acclaimed one of the most important Finnish operas of the twentieth century. Its melodic richness and colorful orchestration recall influences from the composer’s early studies in Leipzig (with Max Reger) and in Moscow. The score, however, does not feature folklorist elements. Raitio’s two full-length operas—Prinsessa Cecilia (Princess Cecilia, 1936) and Kaksi kuningatarta (Two Queens, 1944)—did not suffer the same fate as Juha; they were staged promptly and received favorable reviews, but neither one has enjoyed a revival.

Composers active in the second half of the twentieth century, a period that had a marked increase in the creation and performance of operas by Finnish composers, include Erik Bergman (b. 1911), whose compositional palette continues to embrace the modernism that was part of his vocabulary in the 1960s. In place of the twelve-note technique of his earlier works, however, he has reverted to the use of tonal fields and aleatory rhythms.51 This is evident in Der sjungande Träder (The Singing Tree, 1995), a two-act fairy tale commissioned by the Finnish National Opera.

Among others who contributed to this increase in opera composition are Joonas Kokkonen (1921–96) and Aulis Sallinen (b. 1935). Kokkonen had already abandoned the strict twelve-note technique of his 1960s compositions and moved closer to a triadic foundation upon which to build his tonal musical structures, as exemplified in Viimeiset kiusaukset (The Last Temptations) in 1975.52 This opera was immediately acclaimed at home and abroad, with performances in Sweden, England, Switzerland, Germany, and the United States (at the Metropolitan Opera). A revival was staged in the new opera house at Helsinki in 1994. The success and timelessness of Kokkonen’s opera can perhaps be attributed to the fact that the questions posed in the opera are universally relevant in any age, for any audience.

The story of The Last Temptations concerns a historical figure, the revivalist preacher Paavo Ruotsalainen (1777–1852), who on his deathbed recalls some of the more fateful decisions he had to make during his lifetime, especially in his role as leader of a protest movement against the dogmatic conceptions of religion. By the use of flashbacks, these decisions are brought to the fore, all within the context of Paavo’s unshakable conviction that “God exists.”53 A hymn (derived from preexisting sacred melodies) is sung several times in the course of the opera and serves as a unifying thread, even appearing in the final scene as Paavo prepares himself to cross from this life into that which lies beyond. Spoken dialogue is reserved for moments that are of this world as opposed to the dream world experienced by the preacher; recognizable biblical passages are woven into the opera’s text, thereby accentuating the religious aspects of the opera.

To date, Aulis Sallinen has composed six operas: Ratsumies (The Horseman, 1975), a love story in which Finnish history and mythology are entwined; Punainen viiva (The Red Line, 1978); Kuningas lähtee Ranskaan (The King Goes Forth to France, 1984), a comedy; Kullervo (1992);54 Palatsi (The Palace, 1995), a satirical masterpiece about political corruption; and Kuningas Lear (King Lear, 2000). The Red Line has a libretto by the composer, fashioned from a novel by Illmari Kianto that was published in 1911. The novel deals with issues affecting the Finnish nation, in particular, life lived in the northernmost provinces, where the environment is hostile to one’s survival. The story is set in 1907, the year in which elections were held in Finland to implement a single-chamber Parliament under the new constitution. These elections were especially noteworthy, for they were the first in Europe to allow women the right to vote. The title of the opera refers to the red line that a person had to draw on the ballot in order to cast a vote, a mark that was supposed to improve the living conditions for peasants who daily experienced poverty and deprivation.55 Unfortunately, the promises of those who encouraged the peasants to vote never materialized. Two such peasants, Topoi and Riika, witness the death of their children from malnutrition, and in the epilogue to the opera, Topoi also dies, killed by a bear as he struggles to defend his cattle, the source of the family’s livelihood. The opera ends with Riika calling out to her husband. As the curtain descends, the final stage direction reads: “Topi could no longer reply. He lay motionless in the snow, and from his throat blood was flowing—in a red line.”56

For his next opera, Kullervo, Sallinen drew relevant material from the Finnish epic Kalevala, in which a person named Kullervo appears. He also drew from a drama entitled Kullervo (1864), based on the same epic, by the nineteenth-century Finnish playwright Aleksis Kivi. Sallinen’s opera is a very dark and foreboding work, with revenge and murder at the core of the dramatic events. A rare moment of relief from this endless series of tragic killings comes in Act II, scene iv, when the blind singer offers “The Song of the Sister’s Ravishing” in return for payment of a penny. Sallinen’s most recent opera, King Lear, has two acts divided into ten scenes; the libretto is by the composer, based upon Shakespeare’s play of the same title.57 The score exhibits a musical vocabulary that can best be defined as post-Romanticism, with occasional intrusions of more avant-garde elements. Especially memorable is Sallinen’s use of a solo cello to accompany the scene in which Lear recognizes Gloucester. Equally noteworthy is his reuse of thematic material for dramatic purposes, namely, the melody that first is heard when Lear and Cordelia are brought together appears once again at the very end of the opera when Lear sings his final words over Cordelia’s dead body that lies before him.

(PHOTO, © 1992 KARI HAKLI. COURTESY OF THE FINNISH NATIONAL OPERA)

Eino Rautavaara (b. 1928) has composed in many different genres, but operas are at the center of his work.58 They range from Kaivos (The Mine, 1963) and Apollon ja Marsyas (1970) to Vincent (1987), on the life of Vincent Van Gogh, and Aleksis Kivi (1997). The last-named work is based on the life of Aleksis Kivi (1834–72), who died shortly after his chief work, The Seven Brothers, was panned by a well-respected literary critic August Ahlqvist. Kivi’s novel has since gained the stature of being one of Finland’s greatest classics. The opera focuses on the tension between Kivi and Ahlqvist that arises from the former representing an original new thinker and the latter representing traditional and conservative aesthetic principles. The orchestral forces for the opera are modest (strings, percussion, clarinets, and synthesizer); the melodic writing blossoms into a memorable concluding number, “Song of My Heart,” composed to a poem by Kivi.

One of Finland’s most prolific opera composers is Tauno Marttinen (b. 1912), who has written some fifteen operas to date, of which several are in one act and require only a chamber ensemble.59 They include Mestari Patelin (Master Patelin, 1974), Häät (The Wedding, 1984), and Minna Graucher (1984). Of his full-length operas, Poltettu oranssi (Burnt Orange, 1968), Noitarumpu (The Witch’s Drum, 1976), Faaraon kirje (The Pharaoh’s Letter, 1982), and Seitsemän veljestä (The Seven Brothers, 1989) are representative examples. Marttinen is noted, in particular, for his comic musical dramas, with their inclusion of well-known Finnish folk melodies.

Another composer who has delighted audiences with the more popular musical traditions that he brings to his compositions (including a hefty dose of humor) is Ilkka Kuusisto (b. 1933), director of the Finnish National Opera from 1984 to 1992. Among his operas are Muumiooppera (Moomin Opera, 1974), Sota valosta (War over Light, 1980), Postineiti (The Postmistress, 1992), and Isänmaan tyttäet (Daughters of the Fatherland, 1996).

Other recent contributions to the Finnish opera repertoire include works by Kalevi Aho (b. 1949). and Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952). Aho’s Haönteiselämää (Insect Life, 1996) was created as his entry for an invitational competition sponsored by the Savonlinna Opera Festival, a summer event in Finland of international importance. The opera is based upon a play by Karel and Josef Čapek in which a tramp studies the insect world and comes to the conclusion that it closely mirrors the human realm. Since each insect has its own characteristic music, the opera offers a wide variety of styles, including foxtrot and tango, with jazz rhythms often pervading the melodic material.

Saariaho’s first opera, L’Amour de loin (2000), was highly acclaimed at its Salzburg festival premiere. The libretto by Amin Maalouf is based on a quasi-historical subject about a twelfth-century prince and troubadour who expresses his love for a countess from Tripoli, whom he has heard about but never met. Saariaho’s compositional style embraces electronic and computer devices that are employed to effectively realize a highly individual colorism in her orchestral writing, but these devices are used very subtly, never overshadowing her use of specific instruments, such as the harp, flute, and the lute (to evoke the period in which the opera is set). Influences from Debussy, Satie, and Messiaen are also perceptible in her music.

The number of operatic works by Finnish composers that have been staged—in Finland and abroad—in the course of the past century is nothing short of astounding for such a small country. The brief survey given above is but a cursory glance at the development of a Finnish opera repertoire that embraces a wide variety of compositional styles.60

Spain, Portugal, and Latin America

SPAIN

A notable figure in Spanish opera of the early twentieth century was Manuel de Falla (1876–1946), even though, like Szymanowski, Bartók, and Kodály, he worked mainly in other forms of composition.61 His principal opera is the charming little marionette piece El retablo di Maese Pedro (1923), on an episode from Cervantes’ Don Quixote (Part II, chap. 26).62 The score calls for three singing parts, a boy soprano as narrator, and an orchestra of twenty-five players; it is written in a musical style that cleverly combines archaic features with modern harmonies in an austere but appropriate texture. Falla’s earlier opera, La vida breve, composed in 1905 and first performed in 1913, is less notable for its dramatic qualities than for the ballets in Act II; Falla’s other ballets, El amor brujo and El sombrero de tres picos, are important works in this form.

During the last twenty years of his life Falla was continually occupied with what he intended to be his masterwork, La Atlántida. Although this vast “scenic cantata” was left unfinished, the music was put together from the composer’s sketches by his devoted pupil Ernesto Halffter (1905–85). Portions of La Atlántida were performed in public for the first time, without staging, at Barcelona on November 24, 1961. The first staged production (with the text translated into Italian) took place at La Scala in Milan on June 18, 1962, and a concert version (incomplete) was given at New York in September 1962. Halffter’s final revision of La Atlántida was presented in concert at the 1976 Lucerne festival. Subsequent performances of Halffter’s definitive version have also taken place in concert halls, even though Falla had wanted performances of this work to take place in a religious setting, with its narrative portions illustrated by large paintings.

The text of La Atlántida is taken from an epic poem published in 1878 by Mossén Jacinto Verdaguer. Within a framework of half-pagan, half-Christian mythology, it ranges from the remote geological past over the legendary history of the Spanish peninsula, recounting the exploits of Hercules, the Gardens of the Hesperides, the opening of the Straits of Gibraltar, the destruction of Atlantis, and the founding of Cadiz and Barcelona, finally culminating with a prophetic vision of Columbus’s voyages and the establishment of a Spanish empire in America. In form as well as in some aspects of the subject, the work is reminiscent of Milhaud’s Christophe Colomb. La Atlántida is a monumental combination of oratorio and opera, some three hours in length, requiring for full performance a narrator, a dozen soloists, two choruses, and a huge orchestra. The music has extraordinary variety and breadth; the style in general is markedly different from that of Falla’s earlier works and has an austere, archaic grandeur (especially in the many choral portions) that recalls the spirit of the great sixteenth-century Spanish church composers.