AT THE BEGINNING of the twentieth century, Oscar Hammerstein challenged the unrivaled domination of opera production at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera House by building the Manhattan Opera House. Describing himself as “the little man who’ll provide grand opera for the masses,” Hammerstein planned to stage a repertoire similar to that of the Metropolitan, but with better quality productions and at prices low enough to attract music lovers from all walks of society. The Manhattan Opera House opened on December 3, 1906, with Bellini’s I Puritani, and for the next several years this opera company gave New Yorkers some exceptionally fine productions, with works ranging from Louise, Pelléas et Mélisande, Carmen, and Le Jongleur de Notre Dame to Strauss’s Salome and Elektra. So successful was the New York enterprise, Hammerstein built a similar theater in Philadelphia. By 1910 the rivalry between Hammerstein’s two opera houses and the Metropolitan Opera had become so costly for both companies one of Hammerstein’s sons secretly negotiated the sale of the Philadelphia operation to the Metropolitan company and declared, as part of the sale agreement, that Hammerstein could not produce operas for a period of ten years in New York, Boston, Chicago, or Philadelphia.

All this took place shortly before a major event was to occur at the Metropolitan Opera. On December 10, 1910, the world premiere of Puccini’s “American” opera The Girl of the Golden West (La fanciulla del West) was staged at the very opera house that heretofore had looked with disdain on operas in English or operas by American composers. The libretto, drawn from David Belasco’s play of the same title, is set during the California gold rush era and tells of the triangular love affair of Minnie, the owner of a saloon in a mining town in the Old West, an outlaw, and a sheriff.1 Unlike so many of Puccini’s operas, which end with the tragic death of the heroine, this opera offers a happy ending, with the heroine and the outlaw riding off together to begin a new life. The score differs from earlier Puccini operas in that the flow of musical material does not pause for lyrical set pieces, a feature that may have prevented it from being as popular as some of his other works for the stage.

Still preponderant in American music at the beginning of the twentieth century were German influences, but by this time composers were more thoroughly trained, more ambitious, versatile, and productive, and they were speaking a more authoritative musical language. Nevertheless, it is worth remarking that neither of the two leading composers in this generation, Charles Martin Loeffler (1861–1935) and Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), wrote an opera. Among the principal opera composers of this generation were Walter Damrosch (1862–1950),2 Charles Wakefield Cadman (1881–1946), and three pupils of George Whitefield Chadwick—Frederick Shepherd Converse (1871–1940), Henry Hadley (1871–1937), and Horatio Parker (1863–1919). Their operas had the good fortune to be written at a time when the Metropolitan Opera had started actively seeking works by American composers, even staging a competition for that purpose. Converse’s The Pipe of Desire (Boston, 1906) was the first American opera to be presented at the Metropolitan Opera (1910)—a work in one-act, with a pleasant, tuneful score showing some influence of impressionism. Another of his operas, The Sacrifice, was given at Boston in 1911. Neither opera had a revival. Hadley’s operas include Azora, Daughter of Montezuma (Chicago, 1917) and Cleopatra’s Night (New York, 1920); both were written in a sound conservative style, but only the latter achieved some success, with multiple performances in the 1920 and 1921 seasons of the Metropolitan Opera.

Cleopatra’s Night, however, was not the first American opera to have performances in two consecutive seasons at the Metropolitan Opera. That distinction went to Cadman’s Shanewis, or The Robin Woman, presented there in the 1918 and 1919 seasons. Cadman’s interest in the music of Native Americans, some of which he recorded and published, extended to the authentic tunes he introduced in Shanewis. The score for this opera has an attractive, if superficial, melodic vein, but is slight in substance and rather awkward in dramatic details. The same composer’s A Witch of Salem (Chicago, 1926) enjoyed a modest number of performances.

Mary Carr Moore (1873–1957) also showed interest in Native American material. Her opera The Flaming Arrow (San Francisco, 1922) tells of a Zuni chief whose land has been laid waste by a drought. When a young Hopi brave asks to marry the chief’s daughter, the chief consents, but only if the rains come before “the moon leaves the rim of the hillside.” Fortunately for the lovers, the rains do come, but if they had not, the brave would have been killed by a poisoned arrow. Moore wrote a total of six operas, but only four had professional performances.3

Horatio Parker’s two prizewinning operas, Mona (New York, 1912) and Fairyland (Los Angeles, 1915), are regarded by many as significant American operas that have been unjustly ignored.4 The neglect is certainly not due to any technical shortcomings in the scores, which are sound in craftsmanship, large in conception, distinguished in musical ideas, and well planned for theatrical effect. But the librettos are sadly old-fashioned. Mona, a sufficiently good drama in essence, is markedly in the Romantic style of its day, with a scene laid in ancient Britain and the whole obviously owing much to Tristan und Isolde. Fairyland is one of those combinations of whimsy, symbolism, and vague pantheistic aspiration such as are found in the fairy operas of Rimsky-Korsakov or in Converse’s Pipe of Desire; and Parker’s music is likewise typical of the late Romantic period. Mona is a slightly modernized Tristan, with the same sort of continuous symphonic structure, a system of leitmotifs, opulent harmony, chromatic melody, and avoidance of cadences that characterize its model. Fairyland is somewhat lighter in texture and more diatonic in harmony—Wagner leavened by a dash of late Strauss. Musically, the gravest accusation that can be made against either opera is that the same things had been said before; and it may be regretted that these works had the misfortune to come at a moment when tastes in musical matters were on the verge of radical change.

Part of that change was fostered by the variety of musical entertainment being offered in the theaters of New York City. The advent of Franz Lehár’s Merry Widow at New York’s New Amsterdam Theater in 1907, for example, had a profound influence upon the future growth of operatic productions in America. Hailed by one of the city’s most respected music critics, Richard Aldrich, as the “merriest, maddest thing that has come out of the European continent in many a day,” this operetta soon appeared in theaters across the country. Many factors contributed to the craze for The Merry Widow, but none more so than the waltz, the highlight of Act II.

A major contributor to the American operetta repertoire was Victor Herbert (1859–1924).5 Of his many successful productions, Naughty Marietta (1910) had a particularly triumphant reception. The operetta is set in an American locale (eighteenth-century New Orleans), and although the plot is somewhat thin, the story provides ample opportunity for Herbert to showcase some of his most memorable songs. Another of Herbert’s very popular operettas is Babes in Toyland (1903), adapted for cinema and revived by major opera companies such as the New York City Opera. In 1904 George M. Cohan (1878–1942) brought to the Broadway stage the first American musical comedy, Little Johnny Jones, a patriotic work that included “Give My Regards to Broadway” and “Yankee Doodle Boy,” songs that have retained their popularity to the present day.

Operatic works created, produced, and performed by African Americans were also being staged with considerable success in New York and in many other cities as well, even in London. In Dahomey (1902) by Will Marion Cook (1869–1944) was one such work in which, like so many other African American theatrical productions, dance played a very important role. What was uniquely different about Cook’s use of dance was that the performers in his opera sang while they danced, a feature that attracted the attention of critics and producers alike, with Florenz Ziegfeld borrowing the idea for his own Ziegfeld Follies.

Ragtime was the hallmark of the music by another African American, Scott Joplin (1868–1917), whose move to New York in 1907 came about because he needed a different venue for staging his theatrical works. Joplin’s first opera, Guard of Honor, was performed at St. Louis in 1903 by his newly organized Scott Joplin Opera Company, but no trace of the score has been found. His second opera, Treemonisha, set to a libretto by the composer, was three years in the making. The piano-vocal score, completed in 1911, was published privately that same year and heard in a concert performance at a theater in Harlem in 1915, with Joplin accompanying the singers at the piano. Unfortunately, this performance was not enthusiastically received and even though a review of the published score had praised the work for being a true American opera, no theater manager could be persuaded to produce it during Joplin’s lifetime. Not until the 1970s did productions of Treemonisha begin to take place.6

In the writing of Treemonisha, Joplin did not attempt to mirror the type of European works that were being performed in America. Instead, he marked out his own path and created an opera that reflects black culture at the turn of the century as he experienced it. It was Joplin’s intention to glorify those aspects of black society that were worthy of being retained and to transform those aspects that were not. In the latter category belong superstition and black magic, aspects of the black culture that Treemonisha, a schoolteacher, transformed through education. Treemonisha was also a strong advocate for human rights. Although the opera’s libretto is somewhat stilted and the score filled with a plethora of different types of music (syncopated dance, barbershop quartet, gospel hymns, ragtime, popular ballads, and even a waltz), Treemonisha nevertheless holds a unique place in opera history, one that has only recently begun to be appreciated.

Other contributions to African American opera came in the form of musicals and revues, such as Shuffle Along (1921), a musical revue by Eubie Blake (1883–1983) and Noble Sissle (1889–1975). These two men also collaborated on several other musicals, including Chocolate Dandies (1924) and Shuffle Along of 1933. In all three, dance was an extremely important feature.7

Among the composers strongly influenced by African Americans and whose artistic endeavors were part of a movement that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance were Jerome Kern (1885–1945), Virgil Thomson and George Gershwin, with their principal works written in the period between the two world wars. Kern composed music for a number of musical comedies prior to his collaboration with Oscar Hammerstein II, but in their creation of Show Boat (1927), based upon the novel of the same title by Edna Ferber, they took a bold step in producing a serious music drama that involved interracial relationships, a subject of questionable appropriateness for audiences of their generation. One need look no further than the opening scene—the singing of “Ol’ Man River” by an African American dock worker as he wearily goes about his seemingly endless task of loading cotton bales—to understand that Kern and Hammerstein had created a new type of entertainment, one in which the problems of American society could be brought to the fore in a Broadway musical and in which the conventional happy ending could be abandoned.

Perhaps it was sheer coincidence that in the same year of Show Boat’s critically acclaimed debut at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York, the Metropolitan Opera staged one of its more successful productions of an American opera—The King’s Henchman (1927) by Deems Taylor (1885–1966), with a libretto by Edna St. Vincent Millay. This opera and Peter Ibbetson (1931), also by Taylor, were commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera. Both were expert works in a mild late Romantic style with modern trimmings, well molded to the taste of that large majority of the opera-going public who are pleased with expressive melodies and sensuous harmonies that pleasantly stimulate without disturbing.

An important American historical opera Merry Mount by Howard Hanson (1896–1981) was also commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera and produced there in 1934. The score incorporates many ballets and choruses in a wild, implausible story of Puritan New England. It may be the extravagance of the libretto that has interfered with the full success of Merry Mount, or it may be a somewhat stiff, oratorio-like, undramatic quality and the generally static harmonic and melodic style of much of the music. Yet there is considerable variety of idiom: the love strains of Bradford’s aria “Rise up, my love” and the following duet, and the “Walpurgisnacht” ballets in Act II are particularly remarkable. The work as a whole is able, serious, and uncompromising—a compliment of the sort that opera audiences do not always seem to appreciate. Other American operas staged in the 1930s include yet another commissioned work of the Metropolitan Opera, The Emperor Jones (1933) by Louis Gruenberg (1884–1964), based on Eugene O’Neill’s play; it exploits a neo-primitive orchestra with drum rhythms and choral interludes.

George Antheil (1900–1959), an American living abroad from the 1920s until the early 1930s, created a momentary sensation in Germany with the 1930 premiere of his Transatlantic, one of the first American operas accorded a major production in Europe. The subject of Antheil’s satirical jazz opera, for which he wrote the libretto, focuses on an American presidential campaign with its correlative political vices.8 In this opera his style of writing is strident, propulsive, and strongly influenced by Stravinsky, as in the scenes at the campaign headquarters where the mechanistic music mimics the secretaries busily working at their typewriters. Ezra Pound found parallels between Antheil’s music, with its use of disparate blocks of sound, and Cubism, and he wrote of this relationship in a treatise on Antheil’s harmonic language. Others, like Aaron Copland, found little to praise in Antheil’s style of composition, and indeed Transatlantic had to wait until 1998 before any revivals were staged.

Two unique and enduring examples from the 1930s are Four Saints in Three Acts (1934) by Virgil Thomson (1896–1984) and Porgy and Bess (1935) by George Gershwin (1898–1937). Coincidentally, both operas had all-black casts for their premieres and both were commercially presented on Broadway. The hymn-like dignity and tuneful simplicity of Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts (it is actually in four acts) glimpses a vernacular of a different hue. Gertrude Stein’s text, written expressly for Thomson, represents an abstract threading together of words, out of which evolves a plotless libretto in praise of Spanish saints in general and of St. Theresa of Avila and Ignatius Loyola in particular. Stein viewed words as independent entities divorced from contextual association, mere sounds that, when placed in proper sequential configurations, would evoke meaningful interpretations. The following line from Four Saints in Three Acts is indicative of her style of writing: “Saint Therese [sic] in a storm in Avila there can be rain and warm snow and warm that is the water is warm the river is not warm the sun is not warm and if to stay to cry”9

Thomson’s Four Saints, completed in 1928, did not readily fit into any of the prevailing categories of operatic design, and he had difficulty finding any company willing to stage his work. In 1934 the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music took on the project and achieved a success with its production at the Hartford Athenaeum in Connecticut. The opera was sung, as intended, by an entirely African American cast. Why, one might rightfully ask, did Thomson choose an all-black cast for an opera about Roman Catholic saints and the Counter-Reformation? The composer provided this answer: “Blacks sing so beautifully, and they look so beautiful.”10 The Hartford production sparked enough interest that Four Saints soon thereafter had a run on Broadway and additional productions in Chicago, and has continued to enjoy numerous revivals.

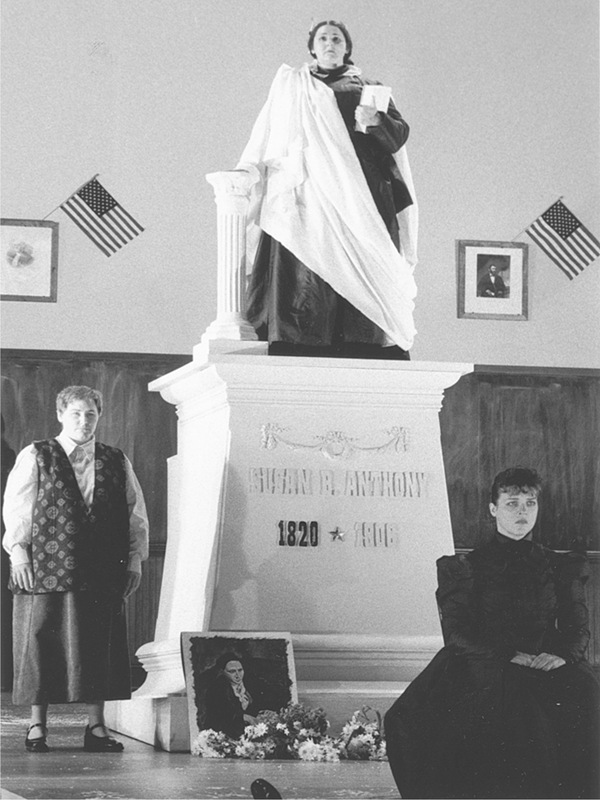

Thomson’s second opera, again with a libretto created for him by Gertrude Stein, was The Mother of Us All, a work commissioned by Columbia University and first performed there in 1947.11 This may be the most original American opera ever written and, some would argue, one of the best. When it was first performed, critics condemned the score for its simplicity and its tonal framework, for indeed it contains no trace of an atonal language and complex rhythmic textures, hallmarks of an avant-garde style. In this score, Thomson concentrated on musically conveying each word in as clear a fashion as possible, for he believed that the sound of the text could, and perhaps would, reveal its meaning.12 The score draws inspiration from music Thomson had heard during his childhood days in Missouri—band concert music, Baptist hymns, and folk music played on the banjo. The theme of the opera is women’s suffrage, seen in the light of nineteenth-century American politics, an era when oratory was prized for its power of persuasion. Susan B. Anthony and Daniel Webster debate the issue of women’s rights in the opening act. Other well-known political figures parade in and out of the scenes (John Adams, Andrew Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant) and the audience is guided through the action by two characters, Gertrude S. and Virgil T, who serve as narrators. Politically charged rhetoric and humorous quips give way in the final scene of the opera to a very moving aria, “All My Life,” sung by “the spirit” of the deceased Susan B. Anthony. As the last notes of this monologue are sung, the curtain slowly descends, but since three measures of silence separate the penultimate chord of the plagal cadence in the orchestral accompaniment from the final C major chord, the audience literally holds its breath until the pianissimo cadential close has sounded.13

George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is true folk opera, the vernacular of the black culture skillfully communicated in sung recitative and in songs patterned after the traditional spirituals.14 The source for the story is Porgy, a 1925 novel by DuBose Heyward that Gershwin read with interest a year after its publication. In 1927 Heyward, with the help of his wife, Dorothy, dramatized the novel, and its successful performances in this form caused yet another transformation of the text in the 1930s. This time Porgy was to become a musical theater work. The idea for such a project was finalized in 1933, when DuBose Heyward, Ira Gershwin, and George Gershwin signed a contract for this purpose: DuBose was to write the libretto; Ira was to provide the lyrics (although DuBose was deeply involved in writing lyrics, too); and George, the music. The title was changed to Porgy and Bess to distinguish the musical adaptation from Heyward’s novel and play. Into this operatic project, Gershwin injected his long-held interest in the blues, jazz, and ragtime to create an American masterpiece.

The setting for the opera is the 1920s in a section of Charleston, South Carolina, known as Catfish Row, where its inhabitants daily experience extreme poverty, love, sex, religion, and violence, and where the Gullah dialect is spoken. In place of the spirituals that Heyward called for in his play, Gershwin substituted newly composed songs, but he seems not to have escaped the influence of the spirituals, for “Summertime” (sung in Act I, scene i) is certainly suggestive of “I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” The communal songs sung by the chorus, representing the Catfish Row residents (who maintain a presence on stage throughout much of the opera), play an extremely important role, for they give voice to the thoughts and feelings of the community in which the named characters are an integral part. The lyrics of at least one number also gave voice to the feelings of those attending performances in the late 1930s. That number was Porgy’s banjo song “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin” (Act II, scene i), which surely must have resonated with those who had experienced and perhaps were still experiencing the Great Depression.

The Broadway premiere of Porgy and Bess took place at the Alvin Theater in New York in October 1935 to mixed reviews. For the most part, the work was enthusiastically received by the audiences, but it puzzled the critics who were at a loss to define its genre—was it an opera or a Broadway musical? That question has yet to be answered, for since its inception, Porgy and Bess has been variously considered a folk opera,15 a musical comedy, a movie musical, and most recently grand opera, after its productions by some major opera companies, including New York City Opera and the Metropolitan Opera. Gershwin drastically cut his original score for the New York premiere, and at the time of a 1941 production, spoken dialogue replaced the sung recitatives. In 1976 the Houston Opera Company produced Porgy and Bess, proclaiming the production represented “the complete unabridged version brought to the stage for the first time,” for it was based upon Gershwin’s short score, the holograph orchestration, and the published piano-vocal score—all of which were prepared before any of the actual staged productions of the 1930s took place and therefore did not reflect the extensive revisions authorized by Gershwin.16

THE 1930S ALSO SAW the first operas by Aaron Copland (1900–1990)17 and Douglas Moore (1893–1969). Copland’s The Second Hurricane (1937) was designed for performance by students enrolled in the Professional Children’s School and the Henry Street Settlement Music School in New York, and by amateur adults cast in the adult roles. The story is set in the midwestern United States and focuses on young people of different personalities and ethnic backgrounds who learn the value of cooperation in the face of a natural disaster. Included in the score are songs, such as the American Revolutionary song “The Capture of Burgoyne”(1777), and choruses to be sung by students and their parents. Orson Welles directed the initial production. Leonard Bernstein prepared a different version of The Second Hurricane for a 1960 television production, and there have been revivals of the staged version, including one at the Henry Street Music School in the mid-1980s.

The only other opera Copland wrote was The Tender Land, representing his contribution to the folk opera repertoire that had become so prevalent in American theaters by the 1950s.18 The libretto, prepared by Horace Everett (pseudonym for Erik Johns), recalls mid-nineteenth-century ideals of a rural society, where country living was seen as the path to moral regeneration. It tells a story about a midwestern farm family during the depression of the 1930s. Martin and Pop, two drifters seeking work, are hired by the Moss family to help with the spring harvest. Martin falls in love with Laurie, the older of the Moss family’s two daughters,19 and at a party attended by both of them the night before Laurie’s graduation from high school, they express their love for each other (in a duet) and make plans to leave the farm together the next morning. In the course of the night, Martin has second thoughts about taking this innocent young girl away from her family and causing her to miss her graduation. He therefore hastily departs before dawn, but when Laurie discovers what has happened, she also takes leave of the farm and the rural community that has nurtured her, thwarting her parents’ dream of having her be the first in the family to graduate from high school.

Copland received a commission from the National Broadcasting Corporation to write an opera for television, but when he presented The Tender Land for consideration, it was rejected. His search for a new venue in which to stage his opera resulted in an agreement with the New York City Opera; a production took place in the spring of 1954 and played to mixed reviews. Further revisions were undertaken for performances at Tanglewood and Oberlin College in 1954 and 1955, respectively. Not until 1987, however, did another reworking of the score generate the kind of enthusiasm one had come to expect from Copland’s other works written in his accessible American style.

Having been granted the composer’s permission, Alvin Brown and Murray Sidlin took the published (1955) version of The Tender Land, restructured it into two acts, added a few recognizable folksongs (in whole or in part) to the party scene of Act II, and introduced two of Copland’s own songs found in his Old American Songs, which were to be sung “spontaneously” by the guests at that same party. Brown heightened the dramatic interest by redefining the motivation for the characters’ actions. Sidlin reduced the scoring from a full orchestra to a chamber ensemble of about thirteen instrumentalists, thereby effectively creating a chamber opera that lent itself admirably to the intimate space of the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven, Connecticut.20 There, to considerable acclaim, The Tender Land enjoyed a run of fifty performances during May and June 1987. As noted by Vivian Perlis in her article previewing the Brown/Sidlin production, Copland’s music stands for “the traditional values that Americans fear have been lost in today’s world.”21

Douglas Moore wrote orchestral and chamber works, art songs, and music for film and theater pieces, but he is best remembered as a composer of operas. All seven of his works in this genre are based on American subjects, of which The Devil and Daniel Webster (1939) is a prime example. This opera is in one long act and is reflective of the folk opera tradition; its mixture of folksong, hymn, and spoken dialogue aids in the painting of a New England scene.22 Stephen Vincent Benet’s libretto focuses on Jabez Stone, who has sold his soul to the devil. On the day of reckoning, Stone’s case is argued by Daniel Webster before a judge and jury representing the devil’s interests. In an appeal to the patriotic spirit of the assembled court, Webster successfully argues in the name of liberty and freedom. This distinctively American subject, presented with Moore’s penchant for good theatrical craftsmanship, reveals characteristics of his subsequent contributions to American opera.

With the end of the World War II, the production of operas by American composers increased significantly, enhanced by the marked rise of local opera groups, both amateur and professional, and the generally favorable opportunities for performance of new works in the United States.23 In the forefront of this postwar activity was Moore, who continued to write operas that combined distinctly American subject matter and musical idiom with good theatrical craftsmanship. This is especially true of his highly successful opera The Ballad of Baby Doe, which had its premiere at the Opera House of Center City, Colorado, in 1956. The libretto by John Latouche is based upon an event that occurred in Colorado in the late nineteenth century. Horace Tabor owned a silver mine that brought him considerable wealth, but when the United States government took its currency off the silver standard, Tabor’s fortunes changed. The mine closed, and he and Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor became impoverished. Tabor, however, never lost faith in the possibility that silver might once again be mined, thereby restoring the family’s wealth. It was for this reason that, shortly before his death, he asked his wife to keep watch over the mine so that no one could lay claim to the property. Thirty-six years later, Baby Doe was found frozen to death at the entrance to the mine, where she had daily maintained her vigil as promised. After the Colorado production, the opera was revised slightly, with the addition of an entire scene in Act II and an aria for Baby Doe, and in this form it was presented in 1958 by New York City Opera. Since that time, the opera has become a staple of the American opera repertoire.

Other operas by Moore include the 1951 Pulitzer Prize–winner Giants in the Earth (1951), which glorifies the pioneer spirit of the Norwegian settlers in the Dakotas as seen through the eyes of O. E. Rölvaag’s novel. This is the first opera by Moore that is full length and entirely sung. Some of his earliest operas were designed to be performed by, or for, young people: The Headless Horseman (1937), a high school opera in one act, drawn from the Washington Irving story;24 The Emperor’s New Clothes (1949); and Puss in Boots (1950). Moore’s last opera, Carrie Nation (1966), focuses on a prohibitionist’s crusade in Kansas.25

OPERAS OF SOCIAL PROTEST that had made their mark in Europe, with music in popular style, were echoed in the United States during the 1930s. Chief among them was Marc Blitzstein’s (1905–64) The Cradle Will Rock (1937), an opera that brought to the stage a story of industrial violence and its effect on the steel industry. Blitzstein completed his score in 1936, but by the time it was readied for a Broadway production, his opera’s libretto mirrored, all too faithfully, events unfolding in the steel and auto industries, where labor was attempting to unionize. The revolutionary tone of the opera was captured in the words of the closing number—“That’s a storm that’s going to last until the final wind blows… and when the wind blows … The Cradle Will Rock.” Unfortunately for Blitzstein, his opera was being sponsored by the Federal Theater Act, a program established during the New Deal era, and since the government did not want to appear to be taking sides over the union issue, the WPA agency decided to postpone the production. Blitzstein and his cast were not to be deterred and they challenged the government’s actions by opening their dress rehearsal to the public. Reaction to their defiant stance was swift; the theater was ordered closed and members of his orchestra and cast were forbidden by their union to appear on any stage not under the sponsorship of the WPA.

As crowds gathered in front of the theater on what was supposed to have been opening night, Blitzstein and his friends, among them Aaron Copland, hastened to rent another theater for the performance. The crowds were told to go to the Venice Theater uptown and by nine o’clock that evening Blitzstein—seated at a piano, alone on a bare stage—began performing the initial numbers, but as he moved through the score, he was joined by his singers who rose from their places in the audience. Some sang from the balcony; others sang from the orchestra section. Even the chorus, grouped in the front rows of the theater, was able to take part, and since the singers were not “on stage,” their participation was entirely legal. The excitement of this historic event was infectious, and for the next several weeks Blitzstein and his cast reenacted the improvised version of their opening night, to the delight of audiences who filled the Venice Theater.

The Cradle Will Rock is best described as a musical theater work; it is in ten scenes, has spoken dialogue alternating with dialogue supported by orchestral accompaniment, and songs in a cultured and clever jazz idiom. The score, dedicated to Bertolt Brecht, whose influence Blitzstein readily acknowledged, represents a bold step in the history of American opera in the sense that Blitzstein defied the stereotypical opera format, believing, as Aaron Copland so eloquently expressed it, that “every artist has the right to make his art out of an emotion that really moves him.”26

Blitzstein’s No for an Answer (1941) is similar in aim and general musical style, though with a wider range of expression, and includes some fine choral numbers. Both works were presented in commercial theaters on Broadway, a further manifestation of Weill’s contention that music should be made accessible to the public. With Regina (1949), an opera based upon Lillian Hellman’s Little Foxes, Blitzstein moved closer to writing a true opera, for although spoken dialogue and Sprechstimme are still present, the work is designed for singers rather than actors. Once again a story was chosen that could be used to make a strong statement against capitalism: it is set in the era after the Civil War and depicts how greed can lead to the decay of society. From the dramatically gripping monologue in Act III to the more mundane passages spiced with gospel hymns and ragtime tunes, Blitzstein created a score that has worn well with time, as recent revivals confirm.27 His works for the stage and his translation and adaptation (as a revised “Americanized” text) of The Threepenny Opera (1952), have secured for Blitzstein a significant place in the annals of American opera.28

Kurt Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper was first introduced to American audiences in 1931 by way of G. W Pabst’s film version. The fact that the film was in German no doubt accounted, in part, for its less than enthusiastic support from audiences and film critics alike during the initial showing in New York City. Early attempts to stage the Brecht-Weill opera for American audiences were not wholly successful. An English-language version entitled The 3-Penny Opera opened in 1933, first in Philadelphia and then in New York City, where it closed after only twelve performances. A second attempt was initiated by Eric Bentley in 1946, but this also proved to be of limited success. Not until Marc Blizstein became a true believer in the merits of Weill’s new type of music theater did an American production rival the triumphal reception of the 1928 Berlin premiere.29 Unfortunately, Weill did not live to see Blitzstein’s English adaptation of Die Dreigroschenoper, brought to the Broadway stage in 1952.

During the fifteen years Weill lived in America, he tried to have the original German-language version of Die Dreigroschenoper performed in New York, but to no avail. A few months before his death, Weill received Blitzstein’s English lyrics for one of the songs from that opera “The Pirate Jenny.” Weill was so impressed with the adaptation, he encouraged Blitzstein to continue creating English lyrics for the entire opera. Blitzstein declined the offer because he was busy with his own compositions, but after attending Weill’s funeral several months later, he found himself ceaselessly drawn to the project.30 By the end of 1951 his adaptation was completed, and among those interested in staging it were some Broadway producers and the New York City Opera, with the latter announcing that its forthcoming spring season would include the Blitzstein adaptation of The Threepenny Opera, “with English lyrics, and some new music.” This information unleashed a wave of protest from those implementing the McCarthy investigation of persons believed to be Communists or Communist sympathizers. On the basis of the opera’s past history, Kurt List, in an article in the New Leader, labeled it “a piece of capitalist propaganda” and called into question an institution willing to promote such a work.31 This controversy caused New York City Opera to postpone the production indefinitely, but Blitzstein, determined that his version should be produced, negotiated a concert performance, with Leonard Bernstein conducting, at the June 1952 Brandeis Festival. The work proved to be an outstanding success, and Blitzstein’s adaptation was praised as being faithful to Brecht’s German original. What followed was a highly acclaimed off-Broadway production in 1953 at the three-hundred-seat Theatre de Lys in Greenwich Village. The production was forced to close because the theater had been reserved for other productions in the 1954–55 season, but when the theater again became available in 1955, The Threepenny Opera resumed its successful run, achieving a total of 2,611 performances before the show closed in 1961. With its subsequent productions at New York City Opera and on and off Broadway, there is no doubt that this one work greatly influenced the future of American musical theater.32

THE POSTWAR PERIOD WITNESSED the blossoming of the uniquely styled American popular opera of New York. This art form had been molded in the 1930s by native composers as well as by those who sought refuge in the United States during World War II. An example of the latter is provided by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht; they were driven out of Germany with the rise of Nazism and the subsequent outbreak of the war but eventually found a safe haven in the United States. Weill was the first to arrive; he came in September 1935 and remained until his death in 1950. Brecht came in 1941 and stayed until 1947, although he had previously visited the United States in the 1930s. There is no mistaking how Weill viewed the potential for his development in his newly adopted country. In an interview with a reporter from the New York Sun, he expressed two very salient points.33 First, he made clear that he was writing music, not for posterity, but for “today,” and that this music was designed to be accessible to a more representative public than the limited audiences for whom he had composed during the earlier European phase of his career. Second, he wanted very much to participate in the development of a musical-dramatic form that eventually would evolve into “American opera.”

One of the first opportunities Weill had to create a theater piece for American audiences came with Johnny Johnson (1936), a story about a simple soldier in World War I whose hatred of violence and war causes him to find unusual ways to spread the gospel of peace, even on the battlefield. Two years later Knickerbocker Holiday (1938) opened on Broadway; this musical includes “September Song” (one of Weill’s best-known Broadway songs). Following close on the heels of this successful production were others that Weill composed for Broadway, among them Lady in the Dark (1942), with lyrics by Ira Gershwin; Street Scene (1947), with a libretto by Elmer Rice; and Lost in the Stars (1949), based upon Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country.34 Street Scene and Lost in the Stars entered the repertory of the New York City Opera in 1959 and 1958, respectively, the years when that institution was committed to performing American opera.

In 1930, before Weill immigrated to the United States, he attended a production of Elmer Rice’s Street Scene (in a German translation) and was very much taken with the play. Rice had won a Pulitzer Prize for this play in 1929, and in 1931 it was made into a commercially produced film. The drama views a cross-section of life lived in a sordid New York tenement, the very environment in which Rice himself grew up. Love, jealousy, murder—these are the ingredients that fuel the dramatic action, which takes place on a sweltering hot summer day.

Weill met Rice in 1936 during a rehearsal of Johnny Johnson and asked him to collaborate in the writing of an opera based on the play. His request initially met with resistance, but a decade later Rice agreed to the proposal, He, together with Weill and Langston Hughes, the lyricist, refashioned the play for a musical setting. Spoken dialogue links the twenty-one vocal numbers. All of them are exceptionally varied; they range from jazz-influenced material and popular songs to large choral scenes and arias reminiscent of Puccini. The overture dwells upon two recurring motifs: one is a melodic motif associated with a vocal number, “Lonely House,” sung by Sam Kaplan; the other is a rhythmically syncopated instrumental motif. Although the word opera was not used in the publicity for the premiere, several reviews of the opening night event did use that word in the headlines.35 That Weill intended to set a new standard for works produced on Broadway is made clear in a letter addressed to the cast before the initial New York performance. In that letter he noted that Street Scene was “the fulfillment of his dream to have serious dramatic musicals staged on Broadway.”36

Other operas staged during the 1958 and 1959 seasons by the New York City Opera included The Taming of the Shrew (1953) by Vittorio Giannini (1903–66); Tale for a Deaf Ear (1957) by Mark Bucci; and The Triumph of Saint Joan (1959) by Norman Dello Joio (b. 1913).37 As early as the 1930s, Giannini had distinguished himself as a composer of American opera, but interestingly his earliest works in this genre, Lucedia (1934) and The Scarlet Letter (1938), had their premieres in Germany. In the 1960s the Ford Foundation, in an effort to promote American opera, commissioned Giannini to compose a work that would fulfill that purpose. The resulting work was The Harvest (1961), set in the American Southwest at the beginning of the twentieth century. Another of his operas that came to the stage in 1967 was The Servant of Two Masters, a two-act comedy after Goldoni. Of all his operas, none exceeded the popularity of The Taming of the Shrew, a work in which Giannini makes use of leitmotifs to create a sense of musical characterization.

Other more or less successful works by composers in the United States that were produced in the immediate post–World War II decades are The Warrior (1947) and The Veil (1950) by Bernard Rogers (1893–1968); The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1950) by Luka Foss (b. 1922); The Mighty Casey (1953), a one-act opera about a baseball player that draws upon a jazz idiom and popular songs, and A Question of Taste (1989) by William Schuman (1910–92); The Ruby (1955) by Dello Joio; The Hero (1965), an opera for television by Mark Bucci (b. 1924);38 The Wife of Martin Guerre (1956) by William Bergsma (b. 1928); The Good Soldier Schweik (1958) by the talented Americanborn Czech composer Robert Kurka (1921–57);39 and The Crucible (1961), a four-act opera by Robert Ward (1917–94).40 The last-named opera was drawn from Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, which had its premiere in 1952. Miller’s play is set in Salem, Massachusetts, at the height of the witch hunts and trials that took place in 1692. Both the play and the opera were intended to be allegorical representations of the McCarthy “witch hunt” of U.S. citizens believed to be card-carrying members of the Communist party, which took place in the 1950s. Ward’s opera incorporates a wide range of conservative compositional styles that reflect the music of Hindemith, Puccini, Protestant hymnody, and Broadway’s popular song repertoire of the 1940s.

The first American woman to have an opera performed in Europe by a major performing company was Louise Talma (1906–96) with The Alcestiad (1962). Her score, in which a twelve-note technique is integrated into her neo-classical style, was also honored with the Waite Award given by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. In the 1970s Talma wrote several operas on a smaller scale: Voices of Peace (1973), Have You Heard? Do You Know? (1978), and Diadem (1979). Another opera written by an American woman that had its premiere in the 1970s is Women in the Garden (1978; revised 1984) by Vivian Fine (1913–2000). The libretto is drawn from the life and writings of four women: Virginia Wolff, Gertrude Stein, Isadora Duncan, and Emily Dickinson. Two decades later Fine brought forth a second opera that deals with women’s issues, The Memoirs of Uliana Rooney (1994).41

OF ALL THE AFRICAN AMERICAN COMPOSERS of the twentieth century, few have gained greater respect than William Grant Still (1895–1978) whose works, especially his symphonies and ballet, have been heard throughout the United States and abroad. Of those that were staged—Troubled Island (1949), Highway No. 1 U.S.A. (1963), A Bayou Legend (1974), and Minette Fontaine (1985)42—one has attracted considerable attention, for it was the first opera by an African American to receive a performance by a major company, in this case the City Center Opera Company of New York. Troubled Island (1949) was set to a libretto by Langston Hughes; he fashioned it from one of his own plays, Drums of Haiti, which was first staged at Detroit in 1930 and later revised as Emperor of Haiti, at Cleveland. The story is set in Haiti and concerns the rise to power, and the eventual overthrow, of Jean Jacques Dessalines. Troubled Island was completed in 1941, but Still’s search for a company to stage the opera took another eight years. Although Still requested that a well-known African American singer be assigned to the leading role, he was also very insistent that the cast be interracial, for he wanted his work to be seen as an American, not an African American, opera. Still did not draw upon Haitian folk material for this opera, but he did engage dancers from Haiti to lend an air of realism to the staging.

When the Metropolitan Opera refused to audition his work, Still asked several of his musician friends to help him find a willing producer. City Center finally agreed, but financial difficulties caused several lengthy delays. To help raise financial support for the City Center production, the Troubled Island Fund was established by, among others, Fiorello LaGuardia, mayor of New York; the president of the fund was none other than Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the then president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Although relatively little money was raised by the fund, it called attention to the seriousness with which the public viewed the production of this work. The contract that Still signed with City Center called for three performances, and although the audiences were enthusiastic in their response to the opera, that was the total number given. Perhaps if the production had not been scheduled at the very end of the 1949 season, additional performances might have been arranged. Since that time, Troubled Island has had a number of revivals, including one designed for television in 1981.43

OVER THE COURSE OF SEVERAL DECADES, the American musical has often elevated itself to a stature deemed acceptable by opera companies, as several works discussed above have shown. This growth toward American popular opera was most significant in the 1950s, but examples continued to make themselves known throughout the second half of the century, such as Arthur Loesser’s Most Happy Fella. This musical came to Broadway in 1956, then was staged by Cincinnati Opera before being brought into the repertoire of the New York City Opera in 1991.44 Loesser drew his libretto for Most Happy Fella from Sidney Howard’s 1924 Pulitzer Prize–winning drama They Knew What They Wanted, set in California’s wine country. Although Loesser has insisted that Most Happy Fella is “merely a musical with a lotta music,” his score (with orchestrations by Dan Walker) offers the richness of sound that plays well in a large theater, a harmonic language that is bold and dramatically effective, and a structure that is enlivened with almost continuous use of music.

Among composers who were not hesitant to declare the Broadway musical theater idiom to be a wellspring for the creation of American national opera was Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), internationally famous as a conductor and as the composer of West Side Story (1957). In the year before the production of West Side Story, Bernstein remarked that “the American musical theater has come a long way, borrowing this from opera, that from revue, the other from operetta, something else from vaudeville—and mixing all the elements into something quite new, but something which has been steadily moving in the direction of opera.”45 In 1944 Bernstein turned his ballet Fancy Free, which is about three sailors who come ashore to explore the sights and sounds of New York City, into an opera. One of the popular songs from that production is “New York, New York.” From this point forward, Bernstein continued to delve into the everyday drama of the city as source material for future musical productions. Wonderful Town (1953), for example, is set during the Great Depression and reveals the pulse of New York City as Bernstein remembered it.

In 1952 Bernstein produced his first opera, Trouble in Tahiti; thirty years later he composed his second, A Quiet Place, intended as a sequel to Trouble in Tahiti. Bernstein originally planned to have both operas produced as a double bill, using a before-and-after format to show changes in family relationships over a twenty-five-year period, but the juxtaposition of the two operas in a production at Houston did not achieve the kind of emotional and psychological impact he had envisioned. Bernstein withdrew the operas and revised A Quiet Place so that it could totally envelop the earlier opera: Act I is derived solely from A Quiet Place. Act II begins with the first half of Trouble in Tahiti, continues with a brief section from A Quiet Place, and concludes with the remaining sections of Trouble in Tahiti. Act III is from A Quiet Place. The revised opera, entitled A Quiet Place and Trouble in Tahiti, was staged first in Milan (1984), where it was heralded as “the most American of American operas,” and then in Washington, D.C. (1984), where it was reviewed as a possible first step toward the “Great American Opera.”46

In his creation of West Side Story, Bernstein composed a score that is structured similarly to his orchestral compositions, with much of the musical material growing out of the melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic cells of the prologue.47 The idea for West Side Story came initially from Jerome Robbins, who suggested that Bernstein adapt the plot of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet for an operatic-styled musical in which “drama, singing, and choreographic action would be of equal importance.”48 The resulting work, with a libretto by Arthur Laurents and exceptionally well-crafted lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, is a love story that takes place among rival street gangs on New York’s West Side. These gangs have no regard for the older generation or for persons in positions of authority, and their bitter hatred for each other causes the tragic death of one of the lovers. In the end, love triumphs over gang violence and brings a measure of hope to those whose lives have been mired in poverty and despair. With this work, Bernstein introduced Broadway audiences to a new type of musical: it presents a tragedy, with a message that shocked the public, and offers a score that was considered novel and adventuresome for the era in which the initial production took place. West Side Story was quick to gain international attention and in so doing forever altered the stereotypical concept of American musical theater. Here dance serves as a function of the drama, not as a mere decorative diversion, and musical styles vacillate between contemporary jazz (associated with the Jets’ dance numbers) and “south of the border” Latin rhythms (connected with the Sharks, a Puerto Rican gang), between popular song and quasi-operatic arias.

When is a “musical” really an “opera” in disguise? That question has come up repeatedly with several works that have premiered on Broadway, among them Bernstein’s Candide (1956) and Stephen Sondheim’s (b. 1930) Sweeney Todd (1979). Their creators insist their works are musicals, not operas.49 To be sure, neither genre is easy to define, for Broadway productions have made their way uptown to the stages of the Metropolitan Opera and the New York City Opera,50 and operas, such as Bizet’s Carmen, have reappeared, albeit usually in a different guise, on Broadway.51 Nevertheless, what the Sondheim and Bernstein scores hold in common are musical-dramatic structures related to the operatic traditions represented by Singspiele and opéras comiques.

The formative years of Sondheim’s career were strongly influenced by Milton Babbitt (1916–2001), with whom he studied musical analysis and composition, and Oscar Hammerstein II, with whom he assisted in the creation of four musicals. Also important was his role as co-lyricist for Bernstein’s West Side Story and as lyricist for Gypsy, with music by Jules Styne. Both productions prepared the way for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), Sondheim’s first professionally staged musical, for which he wrote both the lyrics and the music. The 1970s saw a number of Sondheim’s works staged on Broadway, including A Little Night Music (1973) and Sweeney Todd.

The genesis for Sondheim’s version of Sweeney Todd came principally from two sources: the movie Hangover Square (1945), with a film score by Bernard Herrmann (1911–75), and Christopher Bond’s Sweeney Todd, a play derived from the original Sweeney Todd play of 1842 by George Dibdin. In both the Dibdin and Bond plays, language is used to differentiate the social strata of the characters: the speeches of Todd, the judge, and the two young lovers are in iambic meter; the dialogue for the other characters is written in blank verse. This same distinction between “colloquial prose and blank verse” is retained in Sondheim’s melodramatic rendering of the Sweeney Todd story, in which music accompanies nearly three-fourths of the total production.52 His score is very complex; it abounds with a wide variety of songs (ballads, burlesques, patter, and parlor songs) and relies upon recurring motifs, many of them related to the church and ballroom music, to support the overall structure. In this, Sondheim’s music shows influences from the works of Britten, Vaughan Williams, Stravinsky, and especially Wagner.

THE ULTRACONSERVATIVE STYLE in American opera was represented at mid-century by Vanessa, a large-scale, four-act work that had its premiere at the Metropolitan Opera in 1958 and for which the composer, Samuel Barber (1910–81), was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.53 The opera, with a libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti, is set in an unspecified northern European country at the beginning of the twentieth century. Vanessa has been waiting twenty years for her lover to return to her, but instead of her lover appearing it is Anatol, the son of her lover, who arrives and confirms that his father is dead. Vanessa and her niece, Erika, are attracted to Anatol. Erika and Anatol have an affair and she becomes pregnant. Vanessa, unaware of Erika’s condition, falls in love with Anatol and they go off together to Paris. Erika is left at home to await the arrival of someone who will become her true love. Notable numbers in this opera include Erika’s ballad “Must the Winter Come So Soon,” Vanessa’s aria “Do Not Utter a Word,” and the canonic quintet of Act IV, “To Leave, to Break, to Find, to Keep.” The orchestra plays a powerful and cinematic role in this opera. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the scene in which Erika refuses Anatol’s offer of marriage. Against her repeated rejections of his offer, the orchestra overpowers her protestations with thematic motifs that foretell the outcome of the opera.

Vanessa was so well suited for the stage and contained so many excellent musical numbers that it was not unreasonable for the public to expect Barber’s next major opera, commissioned for the gala opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s new home at Lincoln Center, to be just as theatrically and musically effective. Unfortunately, the inaugural production of Antony and Cleopatra (1966) did not satisfy the public’s expectations and the opera was withdrawn. It was later revised and presented by the Juilliard School of Music in 1973, but the revision did little to change the public’s evaluation of the work.

In Barber’s chamber opera A Hand of Bridge four singers give the appearance of concentrating on the playing of the game, yet all the while they are letting their minds drift off to thoughts of their secret escapades—all of which are revealed as asides to the audience throughout the opera. The harmonic underpinning of the accompaniment vacillates between E minor and E major, with the E minor seemingly reserved for those passages in which a character alludes to his or her marital indiscretions.

More varied and adventurous, though still not involving any radical break with tradition, has been the work of Samuel Barber’s close friend and colleague Gian Carlo Menotti (b. 1911), a theater composer of the order of Puccini and the verismo school. Menotti’s musical style is eclectic, drawing upon heterogeneous elements with a single eye to dramatic effect, of which he is an unerring master. He writes his own librettos, and he often serves as director for his musical productions. Conspicuous among his many successful works for the stage are The Medium (1946), an unashamed melodrama perfectly matched by equally melodramatic music; a short comic opera The Telephone (1947); and his first full-length opera, The Consul (1950), a compelling treatment of the tragedy of homeless persons in an indifferent world.54 Amahl and the Night Visitors, originally produced on television in 1951, has become a popular classic, performed annually during the Christmas holiday season.

It is not necessary to make extravagant claims for Menotti’s musical originality in order to recognize that he was one of the very few serious opera composers on the American scene in the 1950s who thoroughly understood the requirements of the theater and made a consistent, sincere attempt to reach the large opera-loving public; his success is a testimonial to the continuing validity of a long and respectable operatic tradition. Critics of Menotti contend that he reached a peak of creativity with The Saint of Bleecker Street (1954) and that his subsequent works for the theater—Help! Help! The Globolinks! (1969), The Most Important Man (1971), Tamu-Tamu (1973), and The Hero (1976)—provided only a faint reminder of the mastery he had achieved in earlier years. Menotti, undaunted by adverse criticism, has continued composing new operas. Some of his more recent creations include Goya (1986) and The Wedding (1988), a comic opera that had its premiere in Seoul, Korea.

The Saint of Bleecker Street is set in New York’s Little Italy and focuses on the conflict between Annina, a religious mystic who wants to become a nun, and her brother, Michele, who has absolutely no regard for religion and curses her decision to take her vows. Annina is a very sickly person, but she is sought after by those in the Italian community who believe her supreme faith can work miracles. Michele is a hot-tempered person who, in a fit of jealous rage, kills his mistress and then is forced to live the life of a fugitive to escape imprisonment. Michele’s hardness of heart toward his sister continues to the very end of the opera, for even as death overtakes her sickly body, Michele cannot come to terms with her religious beliefs. Menotti’s setting of the opera includes considerably more choral writing than is found in most of his other opera scores.

Stravinsky, along with many other émigré composers, sought refuge in the United States at the onset of World War II.55 His interest in setting an opera to an English-language text was expressed soon after his arrival, especially after he became acquainted with the phenomenal success Menotti had achieved in the 1940s with the Broadway productions of The Telephone and The Medium. He, however, did not find a suitable subject to bring to the operatic stage until 1947, when he visited an exhibition in Chicago. There he saw William Hogarth’s pictures entitled The Rake’s Progress, painted in the 1730s. This series of eight pictures portrays a moral fable that is a variant of the Faust legend: a young man sells his soul to the Devil in exchange for the granting of several wishes. The Rake’s Progress (Venice, 1951) is the only full-length opera that Stravinsky composed.56 The libretto was fashioned by W. H. Auden, whom Stravinsky had chosen because of “his special gift for versification,”57 and by Chester Kallman, whom Auden invited to work on the project. This opera, like everything else of Stravinsky’s, has been so much written about that little need be said here. It is the most thorough example in modern times of a return to classical opera. Not only does it consist of separate solo (or ensemble) vocal numbers, accompanied by a small chamber orchestra; its whole texture, and the harmonic and melodic idiom of the music itself, are neo-Mozartean. A harpsichord accompanies the simple recitatives and is also used to dramatically portray the ghostly atmosphere of the graveyard scene, in which it accompanies the playing of the fatal card game. There is a closing “moral” epilogue, as in Don Giovanni; and the mingled tone of spoofing and sentiment throughout is reminiscent of Figaro or Così fan tutte.

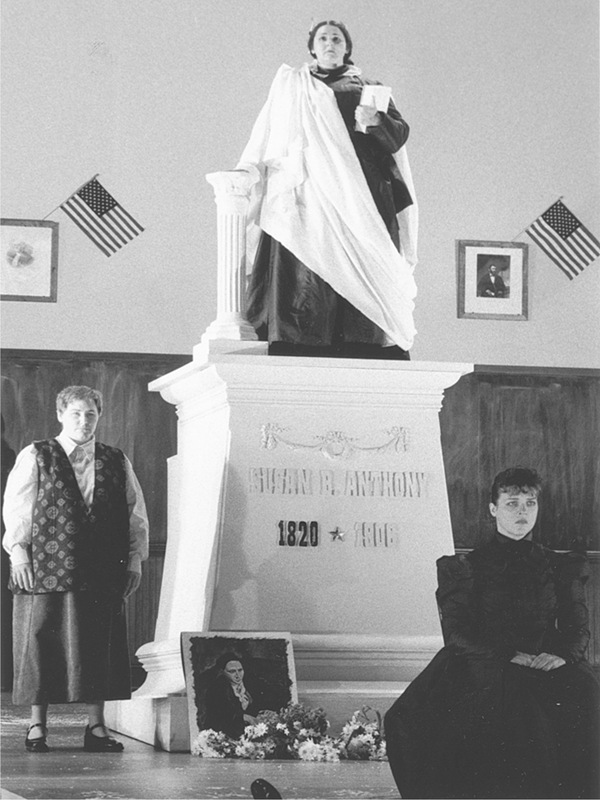

Part of the charm of The Rake’s Progress comes from our being kept constantly aware that its eighteenth-century costume is a disguise that only half conceals the sophisticated complexity of the drama and music—a mask that can be enjoyed for its own inanimate beauty but that at the same time shields the oversensitive spectators from direct contact with the emotions of laughter and pity, thereby allowing them to enjoy those emotions behind an unmoving mask of their own. But the disguise is forgotten when we come to the dialogue between Tom Rakewell and Nick Shadow in the graveyard scene of Act III,58 and the pathetic closing scenes in Bedlam, including Anne’s tender farewell lullaby (example 29.1).

Stravinsky wanted the premiere of this opera to take place in a small theater and, since the text is in English, would have been happy to have it occur in either the United States or England, but no reasonable offers for performances were forthcoming. He had not received a commission to compose The Rake’s Progress and therefore had to find a venue that would provide the requisite financial backing. Eventually the solution came from the Italian government: Stravinsky was offered a substantial fee for the rights to present The Rake’s Progress as the featured attraction and inaugural event of the fourteenth Biennale di Venezia, an international festival of contemporary music. The opera was staged at the Teatro La Fenice.

ROGER SESSIONS (1896–1985) and Hugo Weisgall (1912–97) offer another aspect of American opera, although their works have yet to be fully appreciated by the public. Sessions composed two operas, The Trial of Lucullus (1947) and Montezuma, the latter a monumental atonal score performed first in Berlin (1964) and then in Boston (1976) under the direction of Sarah Caldwell. These avant-garde creations did little to influence a younger generation of composers. What did influence them was Sessions’s teaching and his high regard for the rich heritage of Western music.

This influence can be felt in the music of Weisgall (who studied with Sessions), for several of his operas show an allegiance to the grand operatic tradition, while at the same time exploring new literary and musical territory. Weisgall’s earliest operas are The Tenor (1948–50) and The Stronger (1952); both are in one act and draw upon plays by Wedekind and Strindberg, respectively. In them Weisgall shows his ability to transform powerful psychological dramas into musical works for the stage. His first full-length opera came with Six Characters in Search of an Author (1959), after a 1921 play of the same title by Pirandello. At the beginning of the play, actors are rehearsing a new play by none other than Pirandello, when into their theatrical space come six strangers—characters from a play left unfinished by their creator—searching for a playwright who will complete the drama. This “play within a play” idea is retained by Weisgall and his librettist Denis Johnston; only now the situation involves an “opera within an opera,” with the singers rehearsing The Temptation of St. Anthony by Weisgall. The singers are not enthusiastic about performing The Temptation, nor is the director, who confesses that he really “hates this modern, tuneless stuff, but … now and again we must present them for reasons of prestige.” A further mocking of Weisgall’s style occurs during the rehearsal of an expressionist aria about St. Anthony’s pig; the accompanist calls the singer’s attention to some wrong notes, adding that the piece is “lousy enough with the right notes.” With the arrival of the six strangers, characters from an incomplete opera, Weisgall is given the opportunity to juxtapose different musical styles, ranging from opera buffa to verismo. The harmonic language of this score is unquestionably atonal, yet it has moments of lyric beauty, as in the soliloquy sung by the stepdaughter at her audition.59 There is little of the plot that is easily comprehended by the audience or, for that matter, by the characters on stage, as one of them confesses: “This certainly sounds like a real opera. Nobody knows what is going on.” What Weisgall’s score makes fully comprehensible, however, is the urgency of the strangers’ search for an author.

EXAMPLE 29.1 The Rake’s Progress, Act III, scene iii

The Rake’s Progress—Stravinsky. © 1954 by Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Two other full-length operas by Weisgall include Nine Rivers from Jordan (1968) and Jenny or The Hundred Nights (1976), the latter on a Japanese no drama. They are presented in a very dissonant and rhythmically alive medium and represent well the distinguishing characteristics of Weisgall’s style: florid soaring vocal lines (example 29.2); quotations of familiar tunes (such as “Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” which appears in a violin descant in The Hundred Nights); and excellent ensemble writing.

Weisgall was born in Bohemia, and although he immigrated as a child to America, traces of his Central European background seem ever present in his music, especially in those scores where the atonal and chromatic elements of his harmonic language are infused with expressionism. Evidence of this can be heard in his early works as well as in two works he brought to the stage in the 1990s: The Garden of Adonis, a score Weisgall had worked on over the course of thirty-two years, and Esther, commissioned by San Francisco Opera but first performed by New York City Opera.

EXAMPLE 29.2 Six Characters in Search of an Author

Six Characters in Search of an Author—Weisgall. © 1960 Merion Music Inc. Used by permission.

Throughout his career, Weisgall was a strong advocate of chamber operas, composing them and organizing groups to specialize in their production. One of his last contributions to this repertoire was The Garden of Adonis, the vocal score of which was begun in 1960 but not finished until 1981. The orchestration was completed in 1991, and the following year Adonis had its premiere in Omaha. This production, however, was soon to be overshadowed by the highly acclaimed New York premiere of Esther in 1993. Charles Kondek’s well-crafted libretto is fashioned from the biblical story that relates the extraordinary efforts of one woman to release Israel from its bondage to Persia, a story commemorated in the Jewish holiday of Purim.60 Esther is in three acts of thirty-six scenes and is of “grand opera” proportions. The Schoenberg-style serialism of previous Weisgall operas is also present, a style well suited to the portrayal of this gripping drama. In the words of the composer, the score for Esther is “chromatic but also highly Romantic. Very cinematographic too.”61 In the matter of structure, Weisgall is conventional in that he continues to use set pieces (arias, duets, and ensembles) throughout the three acts. Conventional, too, is Weisgall’s attention to the human voice. Major roles for soprano, mezzo-soprano, contralto, countertenor, tenor, baritone, and bass-baritone are supported by a large orchestra, a chorus, and a children’s chorus. Each character’s personality is fully developed in the course of the opera, but none more so than Esther’s, whose growth from a shy teenager into a courageous spokesperson for her people allows her to emerge as one of the great heroines of opera. Reviews of this opera held one thing in common: Esther offers a powerful evening of musical theater and constitutes one of the major American operas of the twentieth century.62

JACK BEESON (B. 1921), a pupil of Douglas Moore, has composed nine operas. Of these, his best known is Lizzie Borden (1965), which has been presented multiple times on stage and television.63 The Lizzie Borden libretto is based on an incident that occurred in Falls River, Massachusetts, in 1892. The essence of the drama is contained in a rhyme, tauntingly chanted by children (offstage) in the closing scene of the opera:

Lizzie Borden took an ax

And gave her mother forty whacks

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

Indeed, someone did take an ax and murder Lizzie’s stepmother and her father, a wealthy banker in Falls River. The case went to trial and Lizzie was acquitted of the murders. The community members, however, passed their own judgment on the crime, forcing Lizzie to spend the rest of her life shuttered in her father’s house, living off her inheritance. Other characters in the opera include a clergyman and Lizzie’s sister, Margret, who elopes with Captain Jason in Act III.

Beeson’s score appeared in the era of the 1960s when a widening gulf was developing between the self-described modernists, in whose scores serialism played a major role, and the conservatives (or as some prefer to call them, the traditionalists), in whose scores tonality continued to play an important role. The considerable dissonance that pervades Lizzie Borden fittingly expresses the horrors of this gripping drama, but several reviewers of the premiere misinterpreted the harmonically strident music as a reflection of Beeson’s adoption of a twelve-tone procedure. Nothing could be further from the truth, for the composer has consistently defined himself as a conservative. Lizzie Borden is tonally anchored, has set pieces (arias), and occasionally relieves the overall expressionism, in which the score is enveloped, with music related to the Victorian era, such as hymn-like tunes and parlor songs. Gospel hymns and flapper dances are also to be found in another of his operas The Sweet Bye and Bye (1957). In addition to full-length operas, Beeson has composed several chamber operas. They include Hello Out There (1954), based on a one-act play by William Saroyan; Cyrano (1994); and Sorry, Wrong Number (1999), an opera in one act based on a 1944 radio play of the same title.

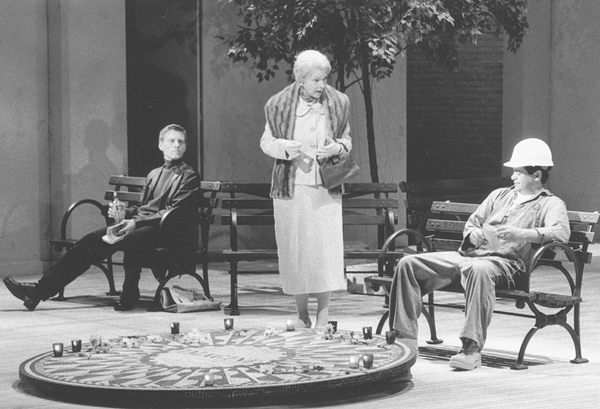

(PHOTO, © 1996 GEORGE MOTT. COURTESY OF GLIMMERGLASS OPERA, COOPERSTOWN, N.Y.)

Beeson gained valuable operatic experience at the Columbia University Opera Workshop, where he served variously as rehearsal accompanist, vocal coach, and assistant conductor. The significance of his association with this group is to be measured by the fact that this workshop was in the forefront of staging the premieres of a number of American operas and performing European works that were deemed too avant-garde for consideration by established opera companies.

New York City, of course, was not the only place where there was notable operatic activity. All around the country opera companies performing in newly constructed theaters were contributing significantly to the rise of American opera. Among some of the more important venues for productions were, and continue to be, those in Chicago, Santa Fe, and Houston, with the last named being the site where a number of operatic works of Carlisle Floyd (discussed below) have been brought to the stage.

Santa Fe was where The Tower (1957), the first of Marvin David Levy’s (b. 1932) three one-act operas, had a successful premiere. The other two, Sotoba Komachi (1957) and Escorial (1958), were staged in New York. Their success brought Levy a commission from the Metropolitan Opera, which he fulfilled in 1967 with Mourning Becomes Elektra. This three-act opera is based on a trilogy of plays by Eugene O’Neill—Homecoming; The Haunted; and The Hunted64—and is set in the 1860s in a New England seacoast town. As originally written, Levy’s score would have been a six-hour production, but the work was greatly reduced for the actual staging. Levy received a second commission from the Metropolitan Opera and composed The Balcony, but a performance never took place.65 Years later, he revisited the score and fashioned it into a musical for Broadway as The Grand Balcony (1989). The accessible style that characterizes Levy’s operatic music is achieved, in part, by the singable material that graces his scores. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Levy does not emphasize angular vocal lines nor does he explore the extremes of the vocal ranges. He does, however, rely upon an occasional use of bitonality and a recurrence of leitmotifs to sharpen the dramatic tension of the musical structure.

Of the many composers who have shared Weisgall’s interest in writing chamber operas is Stephen Paulus (b. 1949), whose masterpiece in this category is The Village Singer (1979).66 This comic one-act opera, set at the turn of the century in New England, is based on a short story written in 1891 about an older woman who was asked to retire from the church choir. She was not about to take this action lightly and decided to compete vigorously with her replacement in the choir loft by singing loudly from her house located next to the church. The success of The Village Singer paved the way for the acceptance of Paulus’s first full-length opera, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1982), drawn from a novel by John Cain. This tragedy concerns ordinary folks living in a small town who become hopelessly involved in a traumatic situation. A year after its premiere, The Postman became the first American opera to be staged at the Edinburgh International Festival. These first two operas were commissioned by the St Louis’s Opera Theater, as were two of his later operas, The Woodlanders (1985) and Woman at the Otowi Crossing (1995).

OVER THE COURSE of the last half century, Carlisle Floyd (b. 1926) has emerged as one of the major contributors to the repertoire of American opera, his dozen or more works bringing to the stage important themes of Americana that are centered on ordinary people caught up in realistic hometown situations. Floyd first gained recognition as an opera composer with Susannah (1955), an immediately popular work that continues to hold the stage. Susannah was first performed at Florida State University, where Floyd was a member of the faculty. A year later New York City Opera staged the opera, followed by that same company’s performance of the work at the Brussels Exhibition in 1958, an event that brought Floyd immediate international recognition. Susannah is based on the apocryphal biblical account of Susannah and the elders, in which the prophet Daniel clears Susannah’s name and reputation by proving the elders had lied. Floyd’s retelling of the story produces a genuine folk opera: the setting is in a rural town in the southern United States, where the revivalist preacher and his congregation assume the roles of Daniel and the elders.67 Traditional revival hymns, square dance music, and even some ballads from Appalachia provide local color for the score. Especially memorable is Susannah’s “The trees on the mountain are cold and bare,” a folk-like song in Act II, scene iii, that is accompanied first by solo harp and then by strings. Woven into the fabric of the score are passages that are spoken, rather than sung, and these are often assigned to the minister. Certain themes or tunes are repeated in the course of the opera, lending a sense of continuity to the whole. For example, several repetitions of the “jaybird song” occur, each time sung by Sam to his sister, recalling memories of their childhood days.

The story revolves around a church congregation wrongly accusing Susannah of not being a virgin, but when the minister comes calling on her and seduces her, he discovers for himself that those accusations are false. After Susannah confides to her brother, Sam, what has taken place in his absence, he vows to kill the minister. His actions, however, provoke the congregation to once again point an accusing finger at Susannah, claiming she goaded him into the murderous act. They also threaten to drive her out of the valley. She, however, holds them at bay, brandishing a rifle to underscore her refusal to leave and as the curtain falls, the audience is left with the knowledge that Susannah has been betrayed by the very people she should have been able to trust. As one writer has pointed out, hypocrisy destroys lives while at the same time it dooms any survivors to a fate worse than death.68

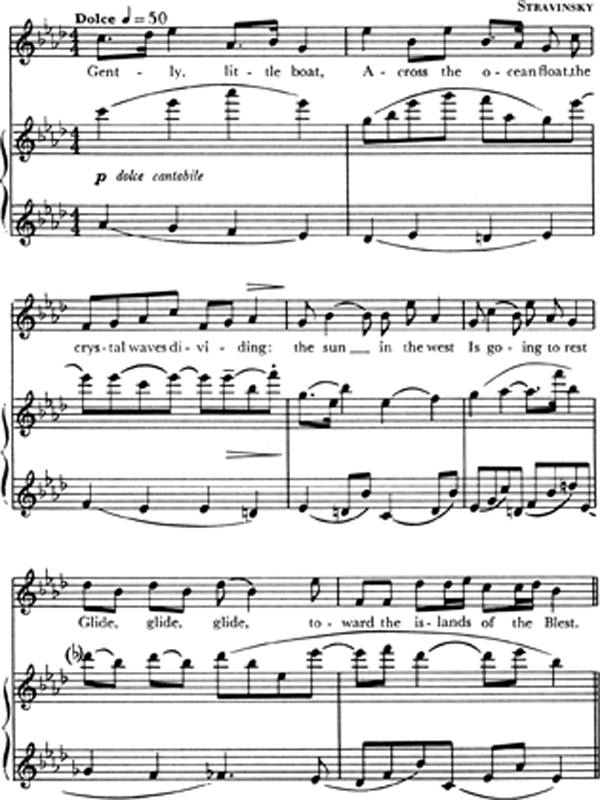

Some of Floyd’s other operas that have gained national attention are Wuthering Heights (1958);69 Of Mice and Men (1970), adapted by Floyd from John Steinbeck’s play rather than from his 1937 novel; Bilby’s Doll (1976), after Esther Forbes’s novel A Mirror for Witches; Willie Stark (1981), after Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 novel All the King’s Men; and Cold Sassy Tree (2000), after Olive Ann Burns’s 1984 novel of the same title. Of Mice and Men chronicles the adventures of two migrant workers who dream of owning their own small ranch. George, and his slow-witted sidekick, Lennie, are continually in difficulty with either the law or their employers, primarily because Lennie cannot stay out of trouble: his fatal urge to caress and cuddle soft living things eventually causes him to accidentally murder his employer’s wife. For his actions, Lennie faces arrest, imprisonment, and most assuredly a death sentence. George cannot bear the thought of Lennie being hurt or scared by the authorities, and he decides to end Lennie’s life in a more humane fashion, reasoning that if he has to die, he might as well die happy. Of Mice and Men is fashioned in a traditional style, with arias, ensembles, and other set pieces. The text plays a dominant role, as it does in many of Floyd’s other works for the stage; his instrumental music accommodates the text with its rhythmic flexibility and light orchestral textures. Of the twelve roles in the opera, only one, Curley’s wife, is for a female.

Willie Stark is a politically charged story that takes place in the depression era and centers on the rise and fall of a southern demagogue. Elements from opera and Broadway-style theater are mixed together here to create a rather strident score that once again makes the projection of the text of paramount importance. Floyd uses various devices to accomplish this, from spoken dialogue and a quasi-Sprechstimme style of recitative to arioso passages in which the orchestral accompaniment is kept very much in the background. Only when the dramatic action reaches an emotional climax does Floyd allow his characters to express themselves in song, as in Willie’s memorable monologue at the end of Act I and Anne Stanton’s intensely emotional episode in Act II.

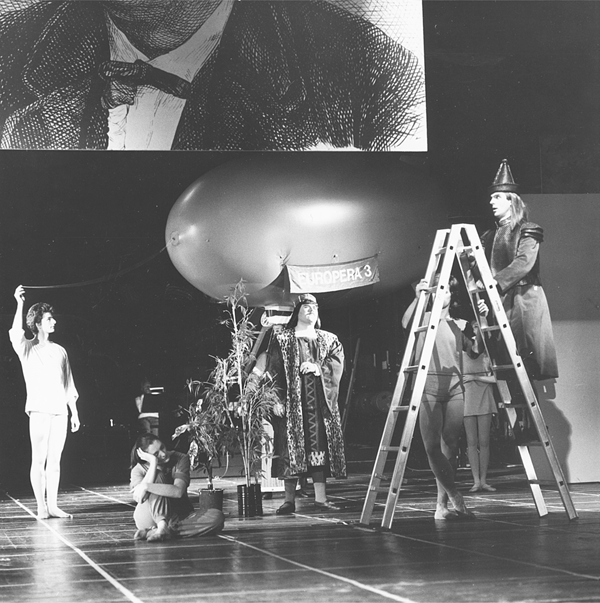

(PHOTO, © 1997 GEORGE MOTT. COURTESY OF GLIMMERGLASS OPERA, COOPERSTOWN, N.Y.)