Map: Top Destinations in Ireland

Traveling as a Temporary Local

Flung onto the foggy fringe of the Atlantic pond like a mossy millstone, Ireland drips with mystery, drawing you in for a closer look and then surprising you. An old farmer cuts turf from the bog, while his son staffs the tech helpline for an international software firm. Buy them both a pint in a pub that’s whirling with playful conversation and exhilarating traditional music. Pious, earthy, witty, brooding, proud, yet unpretentious, Irish culture is an intoxicating potion to sip or slurp—as the mood strikes you.

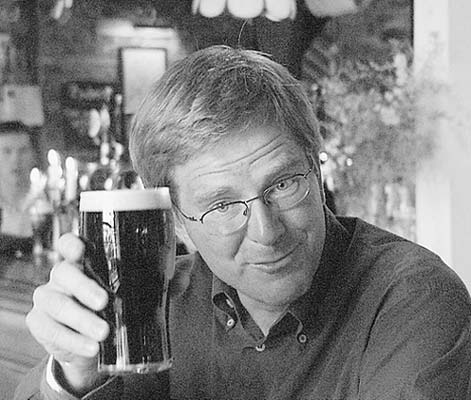

This book breaks Ireland into its best big-city, small-town, and rural destinations. It gives you all the information and opinions necessary to wring the maximum value out of your limited time and money in each of these locations. Experiencing Irish culture, people, and natural wonders economically and hassle-free has been my goal for three decades of traveling, tour guiding, and travel writing. With this new edition, I pass on to you the lessons I’ve learned, updated for your trip in 2014.

The destinations covered in this book are balanced to include the most exciting big cities and great-to-be-alive-in small towns. Note that this book covers the highlights of the entire island, including Northern Ireland. While you’ll find the predictable biggies—such as the Book of Kells, the Newgrange tomb (at Brú na Bóinne), and the Cliffs of Moher—I’ve also mixed in a healthy dose of Back Door intimacy (rope-bridge hikes, holy wells, and pubs with traditional Irish music). This book is selective. On a short trip, visiting both the monastic ruins of Glendalough and Clonmacnoise is redundant; I cover only the best—Glendalough. There are plenty of great manor-house gardens, but I recommend just the top one—the Gardens of Powerscourt.

The best is, of course, only my opinion. But after spending more than half of my adult life exploring and researching Europe, I’ve developed a sixth sense for what touches the traveler’s imagination. The places featured in this book will give anyone the “gift of gab.”

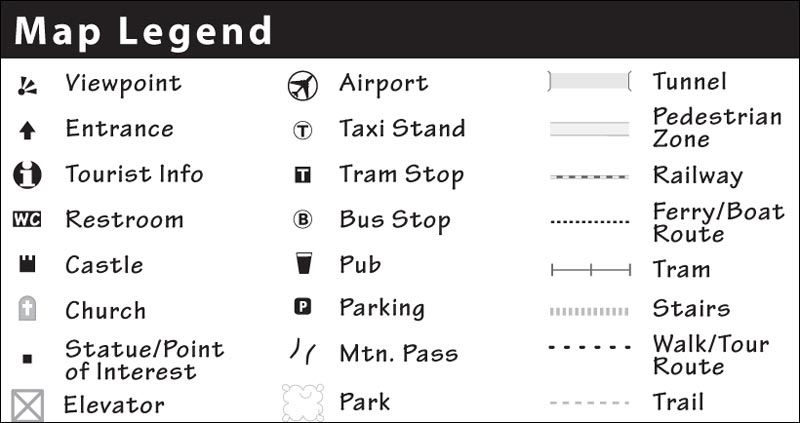

Use this legend to help you navigate the maps in this book.

Rick Steves’ Ireland 2014 is a personal tour guide in your pocket. Better yet, it’s actually two tour guides in your pocket: The co-author of this guidebook is Pat O’Connor. As you can tell from the lad’s name, Pat has long had a travel passion for the Emerald Isle. He’s the Ireland specialist and senior Ireland tour guide at my company, Rick Steves’ Europe Through the Back Door. Together, Pat and I keep this book up-to-date and accurate (though for simplicity, from this point “we” will shed our respective egos and become “I”).

This book is organized by destination. Each is a mini-vacation on its own, filled with exciting sights, strollable lanes, homey and affordable places to stay, and memorable places to eat. In the following chapters, you’ll find these sections:

Planning Your Time suggests a schedule for how to best use your limited time.

Orientation includes specifics on public transportation, helpful hints, local tour options, easy-to-read maps, and tourist information.

Sights describes the top attractions and includes their cost and hours.

Self-Guided Walks take you through interesting neighborhoods, with a personal tour guide in hand.

Sleeping describes my favorite hotels, from good-value deals to cushy splurges.

Eating serves up a range of options, from inexpensive pubs to fancy restaurants.

Connections outlines your options for traveling to destinations by train, bus, and plane, plus route tips for drivers.

Ireland: Past and Present, at the end of the book, gives you a quick overview of Irish history, a look at contemporary Ireland, a taste of the Irish language, and an Irish-Yankee vocabulary list.

The appendix is a traveler’s tool kit, with telephone tips, useful phone numbers and websites, transportation basics (on trains, buses, car rentals, driving, and flights), recommended books and films, a festival list, a climate chart, and a handy packing checklist.

Browse through this book, choose your favorite destinations, and link them up. Then have a great trip! Traveling like a temporary local, you’ll get the absolute most out of every mile, minute, and dollar. As you visit places I know and love, I’m happy that you’ll be meeting some of my favorite Irish people.

This section will help you get started planning your trip—with advice on trip costs, when to go, and what you should know before you take off.

Your trip to Ireland is like a complex play—it’s easier to follow and really appreciate on a second viewing. While no one does the same trip twice to gain that advantage, reading this book in its entirety before your trip accomplishes much the same thing.

Design an itinerary that enables you to visit sights at the best possible times. Note holidays, specifics on sights, and days when sights are closed or most crowded (all covered in this book). To get between destinations smoothly, read the tips in this book’s appendix on taking trains and buses, or renting a car and driving. A smart trip is a puzzle—a fun, doable, and worthwhile challenge.

When you’re plotting your itinerary, strive for a mix of intense and relaxed stretches. To maximize rootedness, minimize one-night stands. It’s worth taking a long drive after dinner (or a train ride with a dinner picnic) to get settled in a town for two nights. Hotels are more likely to give a better price to someone staying more than one night. Every trip—and every traveler—needs slack time (laundry, picnics, people-watching, and so on). Pace yourself. Assume you will return.

Reread this book as you travel, and visit local tourist information offices (abbreviated as TI in this book). Upon arrival in a new town, lay the groundwork for a smooth departure; get the schedule for the train or bus you’ll take when you depart. Drivers can study the best route to their next destination.

Get online at Internet cafés or at your hotel, and carry a mobile phone (or use a phone card) to make travel plans: You can find tourist information, learn the latest on sights (special events, tour schedule, etc.), book tickets and tours, make reservations, reconfirm hotels, research transportation connections, check weather, and keep in touch with your loved ones.

Enjoy the friendliness of the Irish people. Connect with the culture. Set up your own quest for the best pub, traditional music, ruined castle, or ring fort. Slow down and be open to unexpected experiences. Ask questions—most locals are eager to point you in their idea of the right direction. Keep a notepad in your pocket for noting directions, organizing your thoughts, and confirming prices. Wear your money belt, learn the currency, and figure out how to estimate prices in dollars. Those who expect to travel smart, do.

Five components make up your trip costs: airfare, surface transportation, room and board, sightseeing and entertainment, and shopping and miscellany.

Airfare: A basic round-trip flight from the US to Dublin can cost, on average, about $1,000-1,800 total, depending on where you fly from and when (cheaper in winter). Smaller budget airlines may provide bargain service from several European capitals to many cities in Ireland. Consider saving time and money in Europe by flying into one city and out of another; for instance, into Dublin and out of Paris.

Surface Transportation: For a three-week whirlwind trip of my recommended destinations, allow $300 per person for public transportation (trains and buses). For a three-week car rental, allow about $450 per person (based on two people sharing), not including tolls, parking, gas, and insurance. Car rentals are cheapest if arranged from the US. Because Ireland’s train system has gaps, you’ll likely save money by simply buying train and bus tickets as you go, rather than buying a railpass. Don’t hesitate to consider flying, as budget airlines can be cheaper than taking the train (check www.skyscanner.com for intra-European flights). For more on public transportation and car rental, see “Transportation” in the appendix.

Room and Board: You can thrive in Ireland in 2014 on $120 a day per person for room and board (more in big cities). This allows $20 for lunch, $30 for dinner, $10 for snacks or a Guinness, and $60 for lodging (based on two people splitting a $120 double room that includes breakfast). That’s doable, particularly outside Dublin, and it’s easy for many travelers to come in under budget. Students and tightwads can enjoy Ireland for as little as $75 a day ($35 for a bed, $40 for meals and snacks).

Sightseeing and Entertainment: In big cities, figure about $10-15 per major sight (for example, the Book of Kells at Dublin’s Trinity College-$12), $5 for minor ones (climbing church towers), $15 for guided walks, $45 for day-trip bus tours, and up to $75 for splurge experiences (such as the Dunguaire Castle medieval banquet or a flight to the Aran Islands).

An overall average of $30 a day works for most people. Don’t skimp here. After all, this category is the driving force behind your trip—you came to sightsee, enjoy, and experience Ireland. Two sightseeing passes—the Heritage Card and the Heritage Island Explorer Touring Guide—can help you economize and simplify your sightseeing (see “Sightseeing Passes,” here).

Shopping and Miscellany: Figure roughly $2 per postcard, tea, or ice cream cone, and $5 per pint of beer. Shopping can vary in cost from nearly nothing to a small fortune, though good budget travelers find that this has little to do with assembling a trip full of lifelong and wonderful memories.

Depending on the length of your trip, and taking geographic proximity into account, here are my recommended priorities:

| 3 days: | Dublin |

| 5 days, add: | Dingle Peninsula |

| 7 days, add: | Galway, County Clare/Burren |

| 9 days, add: | Aran Islands, Kilkenny/Cashel |

| 11 days, add: | Belfast, Antrim Coast |

| 15 days, add: | Kinsale, Kenmare/Ring of Kerry |

| 19 days, add: | Derry, Connemara, Wicklow Mountains/Valley of the Boyne |

| 21 days, add: | Waterford, Donegal |

(This includes almost everything on the “Ireland’s Best Three-Week Trip by Car” map and itinerary on here.)

July and August are my favorite times—with long days, the best weather, and the busiest schedule of tourist fun. Summer crowds aren’t nearly as dramatic in Ireland as they are in much of Europe. Still, travel during “shoulder season” (May, early June, Sept, and early Oct) is easier and a bit less expensive. Shoulder-season travelers get minimal crowds, decent weather, the full range of sights and tourist fun spots, and the ability to grab a room almost whenever and wherever they like—often at a flexible price. Winter travelers find absolutely no crowds and soft room prices, but shorter sightseeing hours. Some attractions are open only on weekends or are closed entirely in the winter (Nov-Feb). The weather can be cold and dreary, and nightfall draws the shades on sightseeing well before dinnertime. While Ireland’s rural charm falls with the leaves, city sightseeing is fine in the winter.

Plan for rain no matter when you go. The weather can change several times in a day, but rarely is it extreme. Just keep traveling and take full advantage of “bright spells.” Bring a jacket and dress in layers. Daily averages throughout the year range between 42°F and 70°F. Temperatures below 32°F cause headlines, and days that break 80°F—while increasing in recent years—are still rare. For more information, see the climate chart in the appendix.

While sunshine may be rare, summer days are very long. Dublin is as far north as Edmonton, Canada, and Portrush is as far north as Ketchikan on the Alaskan panhandle. The midsummer sun is up from 4:30 until 22:30. It’s not uncommon to have a gray day, eat dinner, and enjoy hours of sunshine afterward.

Your trip is more likely to go smoothly if you plan ahead. Check this list of things to arrange while you’re still at home.

You need a passport—but no visa or shots—to travel in Ireland. You may be denied entry into certain European countries if your passport is due to expire within three to six months of your ticketed date of return. Get it renewed if you’ll be cutting it close. It can take up to six weeks to get or renew a passport (for more on passports, see www.travel.state.gov). Pack a photocopy of your passport in your luggage in case the original is lost or stolen.

Book rooms well in advance if you’ll be traveling during peak season (mid-June-Aug) or any major holidays, such as St. Patrick’s Day (see here).

Call your debit- and credit-card companies to let them know the countries you’ll be visiting, to ask about fees, request your PIN code (it will be mailed to you), and more. See here for details.

Do your homework if you want to buy travel insurance. Compare the cost of the insurance to the likelihood of your using it and your potential loss if something goes wrong. Also, check whether your existing insurance (health, homeowners, or renters) covers you and your possessions overseas. For more tips, see www.ricksteves.com/insurance.

If you’re planning on renting a car in Ireland, bring your driver’s license. If you’re picking up a car at Dublin Airport, consider a gentler small-town start in Trim, and let Dublin be the finale, when you’re rested and ready to tackle the city.

If you plan to hire a local guide, reserve ahead by email. Popular guides can get booked up.

If you’re bringing a mobile device, download any apps you might want to use on the road, such as maps and transit schedules. Check out Rick Steves Audio Europe, featuring hours of travel interviews and other audio content about Ireland (via www.ricksteves.com/audioeurope, iTunes, Google Play, or the Rick Steves Audio Europe free smartphone app; for details, see here).

Check the Rick Steves guidebook updates page for any recent changes to this book (www.ricksteves.com/update).

Because airline carry-on restrictions are always changing, visit the Transportation Security Administration’s website (www.tsa.gov) for an up-to-date list of what you can bring on the plane with you...and what you must check. If you’re flying into Dublin from London, note that some airlines may restrict you to only one carry-on (no extras like a purse or backpack); check with your airline or at Britain’s transportation website for the latest (www.dft.gov.uk).

Emergency and Medical Help: In Ireland, dial 999 for police or a medical emergency. If you get sick, do as the Irish do and go to a pharmacist for advice. Or ask at your hotel for help—they’ll know the nearest medical and emergency services.

Theft or Loss: To replace a passport, you’ll need to go in person to an embassy (see here). If your credit and debit cards disappear, cancel and replace them (see “Damage Control for Lost Cards” on here). File a police report, either on the spot or within a day or two; you’ll need it to submit an insurance claim for lost or stolen railpasses or travel gear, and it can help with replacing your passport or credit and debit cards. For more information, see www.ricksteves.com/help. Precautionary measures can minimize the effects of loss—back up your photos and other files frequently.

Time Zones: Ireland, which is one hour earlier than most of continental Europe, is five/eight hours ahead of the East/West coasts of the US. The exceptions are the beginning and end of Daylight Saving Time: Ireland and Europe “spring forward” the last Sunday in March (two weeks after most of North America) and “fall back” the last Sunday in October (one week before North America). For a handy online time converter, see www.timeanddate.com/worldclock.

Business Hours: In Ireland, most stores are open Monday through Saturday from roughly 10:00 to 17:30, with a late night on Wednesday or Thursday (until 19:00 or 20:00), depending on the neighborhood. Saturdays are virtually weekdays, with earlier closing hours and no rush hour (though transportation connections can be less frequent than on weekdays). Sundays have the same pros and cons as they do for travelers in the US: special events, limited hours, banks and many shops closed, limited public transportation, no rush hours, street markets lively with shoppers.

Watt’s Up? Europe’s electrical system is 220 volts, instead of North America’s 110 volts. Most newer electronics (such as laptops, battery chargers, and hair dryers) convert automatically, so you won’t need a converter, but you will need an adapter plug with three square prongs, sold inexpensively at travel stores in the US. Avoid bringing older appliances that don’t automatically convert voltage; instead, buy a cheap replacement in Europe. Low-cost hair dryers and other small appliances are sold at Dunnes and Tesco stores in bigger cities; ask your hotelier for the closest branch.

Discounts: Discounts (called “concessions” in Ireland) aren’t listed in this book. However, many Irish sights offer discounts for youths (up to age 18), students (with proper identification cards, www.isic.org), families, seniors (loosely defined as retirees or those willing to call themselves a senior), and groups of 10 or more. Always ask. Some discounts are available only for citizens of the European Union (EU).

This section offers advice on paying for purchases on your trip (including getting cash from ATMs and paying with plastic), dealing with lost or stolen cards, VAT (sales tax) refunds, and tipping.

Bring both a credit card and a debit card. You’ll use the debit card at cash machines (ATMs) to withdraw local currency for most purchases, and the credit card to pay for larger items. Some travelers carry a third card, in case one gets demagnetized or eaten by a temperamental machine.

For an emergency reserve, bring several hundred dollars in hard cash in $20 bills. If you have to exchange the bills, go to a bank; avoid using currency exchange booths because of their lousy rates and/or outrageous fees.

Cash is just as desirable in Europe as it is at home. Small businesses (hotels, restaurants, shops, etc.) prefer that you pay your bills with cash. Some vendors will charge you extra for using a credit card, and some won’t take credit cards at all. Cash is the best—and sometimes only—way to pay for bus fare, taxis, and local guides.

Throughout Europe, ATMs are the standard way for travelers to get cash. But stay away from “independent” ATMs such as Travelex, Euronet, and Forex, which charge huge commissions and have terrible exchange rates.

To withdraw money from an ATM, you’ll need a debit card (ideally with a Visa or MasterCard logo for maximum usability), plus a PIN code. Know your PIN code in numbers; there are only numbers—no letters—on European keypads. Although you can use a credit card for an ATM transaction, it only makes sense in an emergency, because it’s considered a cash advance (borrowed at a high interest rate) rather than a withdrawal. Try to withdraw large sums of money to reduce the number of per-transaction bank fees you’ll pay.

For increased security, shield the keypad when entering your PIN code, and don’t use an ATM if anything on the front of the machine looks loose or damaged (a sign that someone may have attached a “skimming” device to capture account information). Some travelers make a point of monitoring their accounts while traveling to detect any unauthorized transactions.

Even in mist-kissed Ireland, you’ll need to keep your cash safe. Pickpockets target tourists. To safeguard your cash, wear a money belt—a pouch with a strap that you buckle around your waist like a belt and tuck under your clothes. Keep your cash, credit cards, and passport secure in your money belt, and carry only a day’s spending money in your front pocket.

For purchases, Visa and MasterCard are more commonly accepted than American Express. Just like at home, credit and debit cards work easily at larger hotels, restaurants, and shops. I typically use a debit card to withdraw cash to pay for most purchases. I use my credit card only in a few specific situations: to book hotel reservations by phone, to cover major expenses (such as car rentals, plane tickets, and long hotel stays), and to pay for things near the end of my trip (to avoid another visit to the ATM). While you could use a debit card to make most large purchases, using a credit card offers a greater degree of fraud protection (because debit cards draw funds directly from your account).

Ask Your Credit- or Debit-Card Company: Before your trip, contact the company that issued your debit or credit cards.

• Confirm that your card will work overseas, and alert them that you’ll be using it in Europe; otherwise, they may deny transactions if they perceive unusual spending patterns.

• Ask for the specifics on transaction fees. When you use your credit or debit card—either for purchases or ATM withdrawals—you’ll typically be charged additional “international transaction” fees of up to 3 percent (1 percent is normal) plus $5 per transaction. If your fees seem high, consider getting a different card just for your trip: Capital One (www.capitalone.com) and most credit unions have low-to-no international fees.

• If you plan to withdraw cash from ATMs, confirm your daily withdrawal limit, and if necessary, ask your bank to adjust it. Some travelers prefer a high limit that allows them to take out more cash at each ATM stop (saving on bank fees), while others prefer to set a lower limit in case their card is stolen. Note that foreign banks also set maximum withdrawal amounts for their ATMs. Also, remember that you’re withdrawing euros, not dollars—so if your daily limit is $300, withdraw just €200. Many a frustrated traveler has walked away from an ATM thinking their card was rejected, when actually they were asking for more cash in euros than their daily limit allowed.

• Get your bank’s emergency phone number in the US (but not its 800 number, which isn’t accessible from overseas) to call collect if you have a problem.

• Ask for your credit card’s PIN in case you need to make an emergency cash withdrawal or encounter Europe’s “chip-and-PIN” system; the bank won’t tell you your PIN over the phone, so allow time for it to be mailed to you.

Chip and PIN: Europeans are increasingly using chip-and-PIN cards, which are embedded with an electronic security chip (in addition to the magnetic stripe on American-style cards). With this system, the purchaser punches in a PIN rather than signing a receipt. Your American-style card might not work at automated payment machines, such as those at train and subway stations, toll roads, parking garages, luggage lockers, and self-serve gas pumps. Luckily, in Ireland, automated payment machines are less prevalent than in the rest of Europe, and so far, Irish ATMs are usually not a problem for American-style cards.

If you have problems using your American card in a chip-and-PIN machine, here are some suggestions: For a debit card, try entering your ATM PIN when prompted. For a credit card, try entering its PIN. (This is not the same as your debit-card PIN; you’ll need to ask your bank for your credit-card PIN.) If your cards still don’t work, look for a machine that takes cash, seek out a clerk who might be able to process the transaction manually, or ask a local if you can pay them cash to run the transaction on their card.

And don’t panic. Many travelers who use only magnetic-stripe cards never have a problem. Still, it pays to carry plenty of euros (you can always use an ATM to withdraw cash with your magnetic-stripe debit card).

If you’re still concerned, you can apply for a chip card in the US (though I think it’s overkill). One option is the no-annual-fee GlobeTrek Visa, offered by Andrews Federal Credit Union in Maryland (open to all US residents; see www.andrewsfcu.org).

Dynamic Currency Conversion: If merchants offer to convert your purchase price into dollars (called dynamic currency conversion, or DCC), refuse this “service.” You’ll pay even more in fees for the expensive convenience of seeing your charge in dollars.

If you lose your credit, debit, or ATM card, you can stop people from using it by reporting the loss immediately to the respective global customer-assistance centers. Call these 24-hour US numbers collect: Visa (tel. 303/967-1096), MasterCard (tel. 636/722-7111), and American Express (tel. 336/393-1111). In Ireland, to make a collect call to the US, dial 001, then the area code and phone number. European toll-free numbers (listed by country) can be found at the websites for Visa and MasterCard.

Providing the following information will allow for a quicker cancellation of your missing card: full card number, whether you are the primary or secondary cardholder, the cardholder’s name exactly as printed on the card, billing address, home phone number, circumstances of the loss or theft, and identification verification (your birth date, your mother’s maiden name, or your Social Security number—memorize this, don’t carry a copy). If you are the secondary cardholder, you’ll also need to provide the primary cardholder’s identification-verification details. You can generally receive a temporary card within two or three business days in Europe (see www.ricksteves.com/help for more).

If you report your loss within two days, you typically won’t be responsible for any unauthorized transactions on your account, although many banks charge a liability fee of $50.

Tipping in Ireland isn’t as automatic and generous as it is in the US, but for special service, tips are appreciated, if not expected. As in the US, the proper amount depends on your resources, tipping philosophy, and the circumstance, but some general guidelines apply.

Restaurants: At a pub or restaurant with waitstaff, check the menu or your bill to see if the service is included; if not, tip about 10 percent. At pubs where you order at the counter, you don’t have to tip.

Taxis: To tip the cabbie, round up. For a typical ride, round up your fare a bit (for instance, if the fare is €9, give €10). If the cabbie hauls your bags and zips you to the airport to help you catch your flight, you might want to toss in a little more. But if you feel as if you’re being driven in circles or otherwise ripped off, skip the tip.

Services: In general, if someone in the service industry does a super job for you, a small tip of a euro or two is appropriate...but not required. If you’re not sure whether (or how much) to tip for a service, ask your hotelier or the TI.

Wrapped into the purchase price of your Irish souvenirs is a Value-Added Tax (VAT); it’s about 23 percent in the Republic and 20 percent in Northern Ireland. You’re entitled to get most of that tax back if you purchase your goods at a store that participates in the VAT-refund scheme. In Ireland, you do not have to meet a minimum purchase amount in order to qualify for a refund.

Getting your refund is usually straightforward and, if you buy a substantial amount of souvenirs, well worth the hassle. If you’re lucky, the merchant will subtract the tax when you make your purchase. (This is more likely to occur if the store ships the goods to your home.) Otherwise, you’ll need to:

Get the paperwork. Have the merchant completely fill out the necessary refund document, called a “Tax-Free Shopping Cheque.” You’ll have to present your passport. Get the paperwork done before you leave the store to ensure you’ll have everything you need (including your original sales receipt).

Get your stamp at the border or airport. Process your VAT document at your last stop in the European Union (such as at the airport) with the customs agent who deals with VAT refunds. Arrive an additional hour early before you need to check in for your flight, to give you time to find the local customs office—and to stand in line. Keep your purchases readily available for viewing by the customs agent (ideally in your carry-on bag—don’t make the mistake of checking the bag with your purchases before you’ve seen the agent). You’re not supposed to use your purchased goods before you leave. If you show up at customs wearing your new Irish sweater, officials might look the other way—or deny you a refund.

Collect your refund. You’ll need to return your stamped document to the retailer or its representative. Many merchants work with a service, such as Global Blue or Premier Tax Free, that has offices at major airports, ports, or border crossings (either before or after security, probably strategically located near a duty-free shop). These services, which extract a 4 percent fee, can refund your money immediately in cash or credit your card (within two billing cycles). If the retailer handles VAT refunds directly, it’s up to you to contact the merchant for your refund. You can mail the documents from home, or more quickly, from your point of departure (using an envelope you’ve prepared in advance or one that’s been provided by the merchant). You’ll then have to wait—it can take months.

You are allowed to take home $800 worth of items per person duty-free, once every 30 days. You can also bring in duty-free a liter of alcohol. As for food, you can take home many processed and packaged foods: vacuum-packed cheeses, dried herbs, jams, baked goods, candy, chocolate, oil, vinegar, mustard, and honey. However, fresh fruits and vegetables and most meats are not allowed. Any liquid-containing foods must be packed in checked luggage, a potential recipe for disaster. To check customs rules and duty rates, visit http://help.cbp.gov.

Sightseeing can be hard work. Use these tips to make your visits to Ireland’s finest sights meaningful, fun, efficient, and painless.

Set up an itinerary that allows you to fit in all your must-see sights. For a one-stop look at opening hours in Dublin, see the “At a Glance” sidebar on here. Most sights keep stable hours, but you can easily confirm the latest by checking with the TI or visiting museum websites.

Don’t put off visiting a must-see sight—you never know when a place will close unexpectedly for a holiday, strike, or restoration. Many museums are closed or have reduced hours at least a few days a year, especially on holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Labor Day (first Monday in May). A list of holidays is on here; check museum websites for possible closures during your trip. In summer, some sights may stay open late. Off-season, many museums have shorter hours.

Make that first sight of the day the one that is the most physically or mentally demanding, while you’ve still got wind in your sails.

Going at the right time helps avoid crowds. This book offers tips on specific sights. Try visiting popular sights very early or very late. Evening visits are usually peaceful, with fewer crowds.

Study up. To get the most out of the self-guided walks and sight descriptions in this book, read them before you visit.

Here’s what you can typically expect:

Entering: Be warned that you may not be allowed to enter if you arrive 30 to 60 minutes before closing time. And guards start ushering people out well before the actual closing time, so don’t save the best for last.

Some important sights have a security check, where you must open your bag or send it through a metal detector. Some sights require you to check daypacks and coats. (If you’d rather not check your daypack, try carrying it tucked under your arm like a purse as you enter.)

Photography: If the museum’s photo policy isn’t clearly posted, ask a guard. Generally, taking photos without a flash or tripod is allowed. Some sights ban photos altogether.

Temporary Exhibits: Museums may show special exhibits in addition to their permanent collection. Some exhibits are included in the entry price, while others come at an extra cost (which you may have to pay even if you don’t want to see the exhibit).

Expect Changes: Artwork can be on tour, on loan, out sick, or shifted at the whim of the curator. To adapt, pick up a floor plan as you enter, and ask museum staff if you can’t find a particular item.

Audioguides: Some sights rent audioguides, which generally offer dry-but-useful recorded descriptions (sometimes included with admission). If you bring your earbuds, you can enjoy better sound and avoid holding the device to your ear. To save money, bring a Y-jack and share one audioguide with your travel partner. Increasingly, sights are offering apps (often free) that you can download to your mobile device.

Services: Important sights may have an on-site café or cafeteria (usually a handy place to rejuvenate during a long visit). The WCs at many sights are free and nearly always clean.

Before Leaving: At the gift shop, scan the postcard rack or thumb through a guidebook to be sure that you haven’t overlooked something that you’d like to see.

Every sight or museum offers more than what is covered in this book. Use the information in this book as an introduction—not the final word.

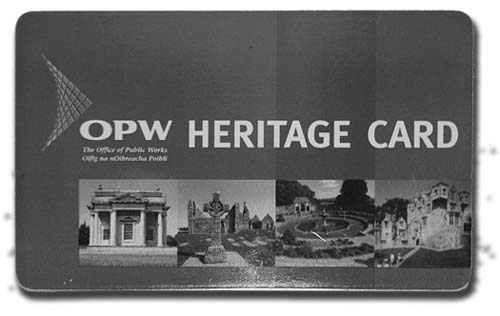

Ireland offers two passes (each covering a different set of sights) that can save you money. The first is smart for anyone, and the second works best for two people traveling together. Twosomes who love to sightsee should get both passes.

Heritage Card: This pass gets you into 96 historical monuments, gardens, and parks maintained by the OPW (Office of Public Works) in the Republic of Ireland. It will pay off if you plan on visiting half a dozen or more included sights over the course of your trip (€21, seniors age 60 and older-€16, students-€8, families-€55, covers entry to all Heritage sights for one year, comes with handy map and list of sights’ hours and prices, purchase at any Heritage sight or Dublin’s tourist information office on Suffolk Street, cash only, tel. 01/605-7700 or 01/647-6592, www.heritageireland.ie, heritagecard@opw.ie). People traveling by car are most likely to get their money’s worth out of the card.

Without the Heritage Card, your costs will add up fast, and you’ll waste time in line. An energetic sightseer with three weeks in Ireland will probably pay to see nearly all 20 of the following sights (covered in this book):

• Dublin Castle-€4.50

• Kilmainham Gaol-€6 (Dublin)

• Brú na Bóinne (Knowth and Newgrange tombs and Visitors Centre)-€11 (Valley of the Boyne)

• Battle of the Boyne-€4

• Hill of Tara-€3 (Valley of the Boyne)

• Old Mellifont Abbey-€3 (Valley of the Boyne)

• Trim Castle-€4 (Valley of the Boyne)

• Glendalough Visitors Centre-€3 (Wicklow Mountains)

• Rock of Cashel-€6

• Reginald’s Tower-€3 (Waterford)

• Charles Fort-€4 (Kinsale)

• Desmond Castle-€3 (Kinsale)

• Muckross House-€7.50 (near Killarney)

• Derrynane House-€3 (Ring of Kerry)

• Garnish Island Gardens-€4 (near Kenmare)

• Great Blasket Centre-€4 (near Dingle)

• Ennis Friary-€3 (Ennis)

• Dún Aenghus-€3 (Inishmore, Aran Islands)

• Glenveagh Castle and National Park-€5 (Donegal)

Together these sights total €90; a pass saves you almost €70 (about $90) per person over paying individual entrance fees. It also moves you through ticket lines more quickly. Note that scheduled tours given by OPW guides at any of these sites are included in the price of admission—regardless of whether you have the Heritage Card—and that the card covers no sights in Northern Ireland.

Heritage Island Explorer Touring Guide: Ambitious travelers covering more ground should seriously consider this €7 pass, which does not overlap with the above Heritage Card sights and gives a variety of discounts (usually 2-for-1 discounts, but occasionally 10-20 percent off) at 90 sights in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. This is a great no-brainer deal for two people traveling together—you just need to buy one Touring Guide, so you’ll save the cost of the guide after only a couple of stops. (Solo travelers might have to go to half a dozen sights before the discounts recoup the initial €7.) At some sites that already have free admission, you may get 10 percent off on purchases at their shop or café. You can buy the guide online or at participating sights, but study the full list of sights first (tel. 01/775-3870, www.heritageisland.com).

Discounted sights mentioned in this guidebook include:

• Trinity College Library (Book of Kells, Dublin)

• St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Dublin)

• Dublin City Hall

• Dublinia

• Old Jameson Distillery (Dublin)

• Guinness Storehouse (Dublin)

• Number Twenty-Nine Georgian House (Dublin)

• Jeanie Johnston Famine Ship (Dublin)

• Irish National Stud (Kildare)

• Gardens of Powerscourt (Enniskerry)

• Avondale House (Wicklow Mountains)

• Bru Boru Cultural Centre (Cashel)

• Rothe House (Kilkenny)

• St. Canice’s Cathedral and Round Tower (Kilkenny)

• Dunbrody Famine Ship (New Ross)

• Waterford Crystal Visitor Centre

• Waterford Museum of Treasures

• Old Midleton Distillery (Midleton)

• Queenstown Story (Cobh)

• Blarney Castle (County Cork)

• Burren Centre (Kilfenora)

• Caherconnell Ring Fort (Burren)

• Aillwee Cave (Burren)

• Atlantic Edge exhibit (Cliffs of Moher)

• Clare Museum (Ennis)

• Kylemore Abbey (Letterfrack)

• Strokestown Park National Famine Museum (Strokestown)

• Somme Heritage Centre (near Bangor)

• Titanic Belfast (Belfast)

• Ulster Museum (Belfast)

• Ulster Folk Park and Transport Museum (Cultra)

• Tower Museum (Derry)

• Belleek Pottery Visitors Centre (Belleek)

• Ulster American Folk Park (Omagh)

I favor hotels and restaurants that are handy to your sightseeing activities. Rather than list hotels scattered throughout a city, I choose two or three favorite neighborhoods and recommend the best accommodations values in each, from dorm beds to fancy doubles with all the comforts. Outside of Dublin you can expect to find good doubles for $100-150, including tax and a cooked breakfast.

A major feature of this book is its extensive and opinionated listing of good-value rooms. I like places that are clean, central, relatively quiet at night, reasonably priced, friendly, small enough to have a hands-on owner and stable staff, run with a respect for Irish traditions, and not listed in other guidebooks. (In Ireland, for me, six out of these eight criteria means it’s a keeper.) I’m more impressed by a convenient location and a fun-loving philosophy than flat-screen TVs and a pricey laundry service.

Book your accommodations well in advance if you’ll be traveling during busy times. Also reserve in advance for Dublin for any weekend, for Galway during its many peak-season events, and for Dingle throughout July and August. See here for a list of major holidays and festivals throughout Ireland; for tips on making reservations, see here.

The Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland have banned smoking in the workplace (pubs, offices, taxicabs, etc.), but some hotels still have a floor or two of rooms where guests are allowed to smoke. If you don’t want a room that a smoker might have occupied before you, let the hotelier know when you make your reservation. All my recommended B&Bs prohibit smoking. While some places allow smoking in the sleeping rooms, breakfast rooms are nearly always smoke-free.

I’ve described my recommended accommodations using a Sleep Code (see sidebar). Prices listed are for one-night stays in peak season, include a hearty breakfast (unless otherwise noted), and assume you’re booking directly (not through an online hotel-booking engine or TI). Booking services extract a commission from the hotel, which logically closes the door on special deals. Book direct.

For most of the hotels I list, I provide a website (which often has a built-in booking form) and an email address; you can expect a response within a day (and often sooner).

Many hotels use “dynamic pricing,” which means room rates change from day to day depending on demand. This makes it extremely difficult to predict what you will pay. For many hotels, I list a range of prices. If the rate you’re offered is at or near the bottom of my printed range, it’s likely a good deal.

Given the economic downturn, hoteliers are often willing and eager to make a deal. I’d suggest emailing several hotels to ask for their best price. Comparison-shop and make your choice.

As you look over the listings, you’ll notice that some accommodations promise special prices to Rick Steves readers who book directly with the hotel. To get these rates, you must book direct (that is, not through a booking site like TripAdvisor or Booking.com), mention this book when you reserve, and then show the book upon arrival. Rick Steves discounts apply to readers with ebooks as well as printed books. Because we trust hotels to honor this, please let me know if you don’t receive a listed discount. Note, though, that discounts understandably may not be applied to promotional rates.

In general, prices can soften if you do any of the following: offer to pay cash, stay at least three nights, or mention this book. You can also try asking for a cheaper room or a discount, or offer to skip breakfast.

When establishing prices, confirm if the charge is per person or per room (if a price is too good to be true, it’s probably per person). Because many places in Ireland charge per person, small groups often pay the same for a single and a double as they would for a triple. Note: In this book, room prices are listed per room, not per person.

Ireland has a rating system for hotels and B&Bs. These stars and shamrocks are supposed to imply quality, but I find that they mean only that the place sporting symbols is paying dues to the tourist board. These rating systems often have little to do with value: One of my favorite Irish B&Bs (also loved by readers) will never be tourist-board approved because it has no dedicated breakfast room (a strict requirement in the eyes of the board). Instead, guests sit around a large kitchen table and enjoy a lively chat with the friendly hosts as they cook breakfast 10 feet away.

Many of my recommended hotels have three floors of rooms and steep stairs; expect good exercise. Elevators are rare except in some hotels, and they’re often very small—pack light, or you may need to send your bags up separately. If you’re concerned about stairs, call and ask about ground-floor rooms or pay for a hotel with a lift (elevator).

Know the terminology: “Twin” means two single beds, and “double” means one double bed. If you’ll take either one, let them know, or you might be needlessly turned away. An “en suite” room has a bathroom (toilet and shower/tub) inside the room; a room with a “private bathroom” can mean that the bathroom is all yours, but it’s across the hall; and a “standard” room has access to a bathroom that’s shared with other rooms and down the hall. Figuring there’s little difference between “en suite” and “private” rooms, some places charge the same for both. If you want your own bathroom inside the room, request “en suite.”

If money’s tight, ask for a standard room. You’ll almost always have a sink in your room, and as more rooms go “en suite,” the hallway bathroom is shared with fewer standard rooms.

Most hotels offer family deals, which means that parents with young children can easily get a room with an extra child’s bed or a discount for a larger room. Call to negotiate the price. Teenagers are generally charged as adults. Kids under five sleep almost free.

Note that to be called a “hotel,” a place technically must have certain amenities, including a 24-hour reception (though this rule is loosely applied). TVs are standard in rooms.

If you’re arriving early in the morning, your room probably won’t be ready. You can drop your bag safely at the hotel and dive right into sightseeing.

Hoteliers can be a great help and source of advice. Most know their city well and can assist you with everything from public transit and airport connections to finding a good restaurant, the nearest launderette, or an Internet café.

Even at the best places, mechanical breakdowns occur: Air-conditioning malfunctions, sinks leak, hot water turns cold, and toilets gurgle and smell. Report your concerns clearly and calmly at the front desk. For more complicated problems, don’t expect instant results.

If you suspect night noise will be a problem (if, for instance, your room is over a pub), ask for a quieter room in the back or on an upper floor. Pubs are plentiful and packed with revelers on weekend nights. (James Joyce once said it would be a good puzzle to try to walk across Dublin without passing a pub.)

To guard against theft in your room, keep valuables out of sight. Some rooms come with a safe, and other hotels have safes at the front desk. I’ve never bothered using one.

Checkout can pose problems if surprise charges pop up on your bill. If you settle your bill the afternoon before you leave, you’ll have time to discuss and address any points of contention (before 19:00, when the night shift usually arrives).

Above all, keep a positive attitude. Remember, you’re on vacation. If your hotel or B&B is a disappointment, spend more time out enjoying the city you came to see.

Compared to hotels, bed-and-breakfast places give you double the cultural intimacy for half the price. While you may lose some of the conveniences of a hotel—such as lounges, in-room phones, frequent bedsheet changes, and being able to pay with a credit card—I happily make the trade-off for the lower rates and personal touches. If you have a reasonable but limited budget, skip hotels and go the B&B way. In 2014, you’ll generally pay €40-55 (about $50-70) per person for a double room in a B&B in Ireland. Prices include a big cooked breakfast. The amount of coziness, teddies, tea, and biscuits tossed in varies tremendously.

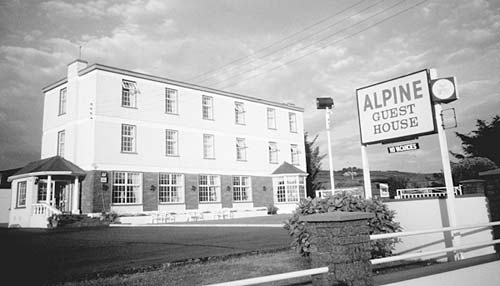

B&Bs range from large guesthouses with 10-15 rooms to small homes renting out a couple of spare bedrooms, but typically have six rooms or fewer. A “townhouse” or “house” is like a big B&B or a small family-run hotel—with fewer amenities but more character than a hotel. The philosophy of the management determines the character of a place more than its size and facilities offered. Avoid places run as a business by absentee owners (their hired hands often don’t provide the level of service that pride of ownership brings). My top listings are run by people who enjoy welcoming the world to their breakfast table.

Book direct. If you buy the lodging vouchers sold by many US travel agents (see sidebar), you’ll only be taking money from the innkeeper and putting it in the pocket of a middleman. If you have a local TI book a room for you, it’ll take a 10 percent commission from the B&B and may charge you up to €5. But if you book direct, the B&B gets it all, and you’ll have a better chance of getting a discount. I have negotiated special prices with this book (often for payment in cash).

Small hotels and B&Bs come with their own etiquette and quirks. Keep in mind that B&B owners are at the whim of their guests—if you’re getting up early, so are they; and if you check in late, they’ll wait up for you. It’s polite to call ahead to confirm your reservation the day before and give them a rough estimate of your arrival time. This allows your hosts to plan their day and run errands before or after you arrive...and also allows them to give you specific directions for driving or walking to their place.

A few tips: B&B proprietors are selective as to whom they invite in for the night. At some B&Bs, children are not welcome. Risky-looking people (two or more single men are often assumed to be troublemakers) find many places suddenly full. If you’ll be staying for more than one night, you are a “desirable.” In popular weekend-getaway spots, you’re unlikely to find a place to take you for Saturday night only. If my listings are full, ask for guidance. (Mentioning this book can help.) Owners usually work together and can call up an ally to land you a bed.

B&Bs serve a hearty “Irish fry” breakfast (for more about B&B breakfasts, see “Eating,” later in this chapter). You’ll quickly figure out which parts of the “fry” you do and don’t like. B&B owners prefer to know this up front, rather than serve you the whole shebang and have to throw out uneaten food. Because your B&B owner is also the cook, there’s usually a quite limited time span when breakfast is served (typically about an hour, starting at about 8:00—make sure you know the exact time before you turn in for the night). It’s an unwritten rule that guests shouldn’t show up at the very end of the breakfast period and expect a full cooked breakfast. If you do arrive at the last minute (or if you need to leave before breakfast is served), most B&B hosts are happy to let you help yourself to cereal, fruit or juice, and coffee; ask politely if it’s possible.

B&Bs are not hotels. Think of your host as a friendly acquaintance who’s invited you to stay in her home, rather than someone you’re paying to wait on you.

Americans often assume they’ll get new towels each day. The Irish don’t. Hang them up to dry and reuse. And pack a washcloth (many Irish B&Bs don’t provide them).

Some B&Bs stock rooms with an electric kettle, along with cups, tea bags, and coffee packets (if you prefer decaf, buy a jar at a grocery, and dump the contents into a baggie for easy packing).

Electrical outlets sometimes have switches that turn the current on or off; if your electrical appliance isn’t working, flip the switch at the outlet. When you unplug your appliance, don’t forget your adapter—most B&Bs have boxes of various adapters and converters that guests have left behind (which is handy if you left yours at the last place).

Most B&Bs come with thin walls and doors. This can make for a noisy night, especially with people walking down the hall to use the bathroom. If you’re a light sleeper, bring earplugs. And please be quiet in the halls and in your rooms (gently shut your door, talk softly, and keep the TV volume low)...those of us getting up early will thank you for it.

Virtually all rooms have sinks. You’ll likely encounter unusual bathroom fixtures. The “pump toilet” has a flushing handle that doesn’t kick in unless you push it just right: too hard or too soft, and it won’t go. (Be decisive but not ruthless.) There’s also the “dial-a-shower,” an electronic box under the showerhead where you’ll turn a dial to select the heat of the water, and (sometimes with a separate dial or button) turn on or shut off the flow of water. If you can’t find the switch to turn on the shower, it may be just outside the bathroom.

Your B&B bedroom might not include a phone. In the mobile-phone age, street phone booths can be few and far between. Some B&B owners will allow you to use their phone, but understandably they don’t want to pay for long-distance charges. If you must use their phone, show them your international calling card (see here) and keep the call short (5-10 minutes max). If you plan to stay in B&Bs and make frequent calls, consider bringing a mobile phone or buying one in Ireland (see here). And if you’re bringing your laptop, look for places with Wi-Fi (noted in my hotel listings). Ask your host about using this service, as some rooms might have better reception than others; usually the ground-floor lobby or breakfast room is your best bet.

A few B&B owners are also pet owners. And, while pets are rarely allowed into guest rooms, and B&B proprietors are typically very tidy, those with pet allergies might be bothered. I’ve tried to list which B&Bs have pets, but if you’re allergic, ask about pets when you reserve.

Remember that you’ll likely need to pay cash for your room. Think ahead so you have enough cash to pay up when you check out.

Hotel chains—popular with budget tour groups—offer predictably comfortable, no-frills accommodations at reasonable prices. These hotels are popping up in big cities in Ireland. They can be located near the train station, in the city center, on major arterials, and outside the city center. What you lose in charm, you gain in savings.

I can’t stress this enough: Check online for the cheapest deals. But be sure to go through the hotel’s website rather than an online middleman.

Chain hotels are ideal for families, offering simple, clean, and modern rooms for up to four people (two adults/two children) for €100-150, depending on the location. Note that couples pay the same price for a room as do families (up to four). Most rooms have a double bed, single bed, five-foot trundle bed, private shower, WC, and TV. Hotels usually have an attached restaurant, good security, an elevator, and a 24-hour staffed reception desk. Of course, they’re as cozy as a Motel 6, but many travelers love them. You can book online (be sure to check their websites for deals) or over the phone with a credit card, then pay when you check in. When you check out, just drop off the key, Lee.

The biggies are Jurys Inn (call their hotels directly or book online at www.jurysinns.com), Comfort/Quality Inns (Republic of Ireland tel. 1-800-500-600, Northern Ireland tel. 0800-444-444, US tel. 877-424-6423, www.choicehotels.com), and Travelodge (also has freeway locations for tired drivers, reservation center in Britain tel. 08700-850-950, www.travelodge.co.uk).

Ireland has hundreds of hostels of all shapes and sizes. Choose yours selectively; hostels can be historic castles or depressing tenements, serene and comfy or overrun by noisy school groups.

You’ll pay about €25 per bed to stay at a hostel. Travelers of any age are welcome, if they don’t mind dorm-style accommodations and meeting other travelers. Most hostels offer kitchen facilities, guest computers, Wi-Fi, and a self-service laundry. Nowadays, concerned about bedbugs, hostels are likely to provide all bedding, including sheets. Family and private rooms may be available but are limited in number, so book ahead.

Independent hostels tend to be easygoing, colorful, and informal (no membership required); www.hostelworld.com is the standard way backpackers search and book hostels these days, but also try www.hostelz.com, www.hostels.com, and www.hostelbookers.com. Ireland’s Independent Holiday Hostels (www.hostels-ireland.com) is a network of independent hostels, requiring no membership and welcoming all ages. All IHH hostels are approved by the Irish Tourist Board.

Official hostels are part of Hostelling International (HI) and share an online booking site (www.hihostels.com). HI hostels typically require that you either have a membership card or pay extra per night.

Travelers wanting to slow down and base themselves in one place for extended periods can rent a cottage or an apartment (sometimes called a “flat” in Ireland). This type of lodging varies greatly, but almost always includes a kitchen and living room. The owners discourage short stays and usually require a minimum one-week rental, plus a deposit.

I focus on short-term-stay sleeping recommendations in this book (B&Bs, guesthouses, and hotels), rather than self-catering options. But if a B&B I’ve listed also offers a worthwhile self-catering option nearby, I’ll mention it.

A variety of organizations specialize in this longer-term alternative. Your most reliable source for places that live up to certain standards is the Irish Tourist Board (www.discoverireland.ie). Another option for apartment, house, and villa rentals is HomeAway.com and its sister site VRBO.com, which let you correspond directly with European property owners or managers.

Airbnb.com makes it reasonably easy to find a place to sleep in someone’s home. Beds range from air-mattress-in-living-room basic to plush-B&B-suite posh. If you want a place to sleep that’s free, Couchsurfing.com is a vagabond’s alternative to Airbnb. It lists millions of outgoing members, who host fellow “surfers” in their homes.

Denis Leary once quipped, “Irish food isn’t cuisine...it’s penance.” For years, Irish food was just something you ate to survive rather than to savor. In this country, long known as the “land of potatoes,” the diet reflected the economic circumstances. But times have changed. A study in 2010 found that the average Irishman was eating half as many spuds as he had a decade before. You’ll find modern-day Irish cuisine delicious and varied, from vegetables, meat, and dairy products to fresh- and saltwater fish. Try the local specialties wherever you happen to be eating.

The traditional breakfast, the “Irish Fry” (known in the North as the “Ulster Fry”), is a hearty way to start the day—with juice, tea or coffee, cereal, eggs, bacon, sausage, a grilled tomato, sautéed mushrooms, and optional black pudding (made from pigs’ blood). Toast is served with butter and marmalade. Home-baked Irish soda bread can be an ambrosial eye-opener for those of us raised on Wonder bread. This meal tides many travelers over until dinner. But there’s nothing un-Irish about skipping the “fry”—few locals actually start their day with this heavy traditional breakfast. You can simply skip the heavier fare and enjoy the cereal, juice, toast, and tea (surprisingly, the Irish drink more tea per capita than the British).

When restaurant-hunting, choose a spot filled with locals, not tourists. Venturing even a block or two off the main drag leads to higher-quality food for less than half the price of the tourist-oriented places. Locals eat better at lower-rent locales. At classier restaurants, look for “early-bird specials,” which allow you to eat well and affordably, but early (about 17:30-19:00, last order by 19:00). At a sit-down place with table service, tip about 10 percent—unless the service charge is already listed on the bill. If you order at a counter, there’s no need to tip.

Picnicking saves time and money. Try boxes of orange juice (pure, by the liter), fresh bread (especially Irish soda bread), tasty Cashel blue cheese, meat, a tube of mustard, local-eatin’ apples, bananas, small tomatoes, a small tub of yogurt (it’s drinkable), rice crackers, trail mix or nuts, plain digestive biscuits (the chocolate-covered ones melt), and any local specialties. At open-air markets and supermarkets, you can get produce in small quantities. Supermarkets often have good deli sections, packaged sandwiches, and sometimes salad bars. Hang on to the half-liter mineral-water bottles (sold everywhere for about €1). Buy juice in cheap liter boxes, then drink some and store the extra in your water bottle. I often munch a relaxed “meal on wheels” in a car, train, or bus to save 30 precious minutes for sightseeing.

Pubs are a basic part of the Irish social scene, and whether you’re a teetotaler or a beer-guzzler, they should be a part of your travel here. “Pub” is short for “public house.” It’s an extended living room where, if you don’t mind the stickiness, you can feel the pulse of Ireland.

Smart travelers use pubs to eat, drink, get out of the rain, watch the latest sporting event, and make new friends. Unfortunately, many city pubs have been afflicted with an excess of brass, ferns, and video games. Today the most traditional atmospheric pubs are in Ireland’s countryside and smaller towns.

Pub grub gets better every year—it’s Ireland’s best eating value. But don’t expect high cuisine; this is, after all, comfort food. For about $15-20, you’ll get a basic hot lunch or dinner in friendly surroundings. Pubs that are attached to restaurants, advertise their food, and are crowded with locals are more likely to have fresh food and a chef than to be the kind of pub that sells only lousy microwaved snacks.

Pub menus consist of a hearty assortment of traditional dishes, such as Irish stew (mutton with mashed potatoes, onions, carrots, and herbs), soups and chowders, coddle (bacon, pork sausages, potatoes, and onions stewed in layers), fish-and-chips, collar and cabbage (boiled bacon coated in bread crumbs and brown sugar, then baked and served with cabbage), boxty (potato pancake filled with fish, meat, or vegetables), and champ (potato mashed with milk and onions). Irish soda bread nicely rounds out a meal. In coastal areas, a lot of seafood is available, such as mackerel, mussels, and Atlantic salmon. There’s seldom table service in Irish pubs. Order drinks and meals at the bar. Pay as you order, and only tip (by rounding up to avoid excess coinage) if you like the service.

I recommend certain pubs, and your B&B host is usually up-to-date on the best neighborhood pub grub. Ask for advice (but adjust for nepotism and cronyism, which run rampant).

When you say “a beer, please” in an Irish pub, you’ll get a pint of Guinness (the tall blonde in a black dress). If you want a small beer, ask for a glass, which is a half-pint. Never rush your bartender when he’s pouring a Guinness. It’s an almost-sacred two-step process that requires time for the beer to settle.

The Irish take great pride in their beer. At pubs, long hand pulls are used to draw the traditional, rich-flavored “real ales” up from the cellar. These are the connoisseur’s favorites: They’re fermented naturally, vary from sweet to bitter, and often have a hoppy or nutty flavor. Experiment with obscure local microbrews (a small but growing presence on the Irish beer scene). Short hand pulls at the bar mean colder, fizzier, mass-produced, and less interesting keg beers. Stout is dark and more bitter, like Guinness. If you think you don’t like Guinness, try it in Ireland. It doesn’t travel well and is better in its homeland. Murphy’s is a very good Guinness-like stout, but a bit smoother and milder. For a cold, refreshing, basic, American-style beer, ask for a lager, such as Harp. Ale drinkers swear by Smithwick’s (I know I do). Caffrey’s is a satisfying cross between stout and ale. Try the draft cider (sweet or dry)...carefully. Teetotalers can order a soft drink.

Pubs are generally open daily from 11:00 to 23:30 and Sunday from noon to 22:30. Children are served food and soft drinks in pubs (sometimes in a courtyard or the restaurant section). You’ll often see signs behind the bar asking that children vacate the premises by 20:00. You must be 18 to order a beer, and the Gardí (police) are cracking down hard on pubs that don’t enforce this law.

You’re a guest on your first night; after that, you’re a regular. A wise Irishman once said, “It never rains in a pub.” The relaxed, informal atmosphere feels like a refuge from daily cares. Women traveling alone need not worry—you’ll become part of the pub family in no time.

Craic (crack), Irish for “fun” or “a good laugh,” is the sport that accompanies drinking in a pub. People are there to talk. To encourage conversation, stand or sit at the bar, not at a table.

In 2004, the Irish government passed a law making all pubs in the Republic smoke-free. Smokers now take their pints outside, turning alleys into covered smoking patios. An incredulous Irishman responded to the law by saying, “What will they do next? Ban drinking in pubs? We’ll never get to heaven if we don’t die.”

It’s a tradition to buy your table a round, and then for each person to reciprocate. If an Irishman buys you a drink, thank him by saying, “Go raibh maith agat” (guh rov mah UG-ut). Offer him a toast in Irish—“Slainte” (SLAWN-chuh), the equivalent of “cheers.” A good excuse for a conversation is to ask to be taught a few words of Gaelic.

Traditional music is alive and popular in pubs throughout Ireland. “Sessions” (musical evenings) may be planned and advertised or impromptu. Traditionally, musicians just congregate and play for the love of it. There will generally be a fiddle, a flute or tin whistle, a guitar, a bodhrán (goatskin drum), and maybe an accordion or mandolin. Things usually get going at about 21:30 (but note that Irish punctuality is unpredictable). Last call for drinks is at about 23:30.

The music often comes in sets of three songs. The wind and string instruments embellish melody lines with lots of tight ornamentation. Whoever happens to be leading determines the next song only as the current tune is about to be finished. If he wants to pass on the decision, it’s done with eye contact and a nod. A ceilidh (KAY-lee) is an evening of music and dance...an Irish hoedown.

Percussion generally stays in the background. The bodhrán (BO-run) is played with a small, two-headed club. The performer’s hand stretches the skin to change the tone and pitch. You’ll sometimes be lucky enough to hear a set of bones crisply played. These are two cow ribs (boiled and dried) that are rattled in one hand like spoons or castanets, substituting for the sound of dancing shoes in olden days.

Watch closely if a piper is playing. The Irish version of bagpipes, the uilleann (ILL-in) pipes are played by inflating the airbag (under the left elbow) with a bellows (under the right elbow) rather than with a mouthpiece like the Scottish Highland bagpipes. Uilleann is Gaelic for “elbow,” and the sound is more melodic, with a wider range than the Highland pipes. The piper fingers his chanter like a flute to create individual notes. When he taps the chanter on his thigh, it closes the end and raises the note one octave. He uses the heel of his right hand to play chords on one of three regulator pipes. It takes amazing coordination to play this instrument well, and the sound can be haunting.

Occasionally, the fast-paced music will stop and one person will sing a lament. Called sean nos (Gaelic for “old style”), this slightly nasal vocal style may be a remnant of the ancient storytelling tradition of the bards whose influence died out when Gaelic culture waned 400 years ago. This is the one time when the entire pub will stop to listen as sad lyrics fill the room. Stories—often of love lost, emigration to a faraway land, or a heroic rebel death struggling against English rule—are always heartfelt. Spend a lament studying the faces in the crowd.

A session can be magical or lifeless. If the chemistry is right, it’s one of the great Irish experiences. The music churns intensely while members of the group casually enjoy exploring each other’s musical style. The drummer dodges the fiddler’s playful bow. Sipping their pints, they skillfully maintain a faint but steady buzz. The floor on the musicians’ platform is stomped paint-free, and barmaids scurry artfully through the commotion, gathering towers of empty, cream-crusted glasses. Make yourself right at home, “playing the boot” (tapping your foot) under the table in time with the music. Talk to your neighbor. Locals often have an almost evangelical interest in explaining the music.

We travel all the way to Ireland to enjoy differences—to become temporary locals. You’ll experience frustrations. Certain truths that we find “God-given” or “self-evident,” such as cold beer, ice in drinks, bottomless cups of coffee, and bigger being better, are suddenly not so true. One of the benefits of travel is the eye-opening realization that there are logical, civil, and even better alternatives. A willingness to go local ensures that you’ll enjoy a full dose of Irish hospitality.

The Irish generally like Americans. But if there is a negative aspect to their image of us, it’s that we are loud, wasteful, ethnocentric, too informal (which can seem disrespectful), and a bit naive.

While the Irish look bemusedly at some of our Yankee excesses—and worriedly at others—they nearly always afford us individual travelers all the warmth we deserve. Judging from all the happy feedback I receive from travelers who have used this book, it’s safe to assume you’ll enjoy a great, affordable vacation—with the finesse of an independent, experienced traveler.

Thanks, and have a grand holiday!

From Rick Steves’ Europe Through the Back Door

Travel is intensified living—maximum thrills per minute and one of the last great sources of legal adventure. Travel is freedom. It’s recess, and we need it.

Experiencing the real Europe requires catching it by surprise, going casual...“through the Back Door.”

Affording travel is a matter of priorities. (Make do with the old car.) You can eat and sleep—simply, safely, and enjoyably—anywhere in Europe for $120 a day plus transportation costs. In many ways, spending more money only builds a thicker wall between you and what you traveled so far to see. Europe is a cultural carnival, and time after time, you’ll find that its best acts are free and the best seats are the cheap ones.

A tight budget forces you to travel close to the ground, meeting and communicating with the people. Never sacrifice sleep, nutrition, safety, or cleanliness to save money. Simply enjoy the local-style alternatives to expensive hotels and restaurants.

Connecting with people carbonates your experience. Extroverts have more fun. If your trip is low on magic moments, kick yourself and make things happen. If you don’t enjoy a place, maybe you don’t know enough about it. Seek the truth. Recognize tourist traps. Give a culture the benefit of your open mind. See things as different, but not better or worse. Any culture has plenty to share.

Of course, travel, like the world, is a series of hills and valleys. Be fanatically positive and militantly optimistic. If something’s not to your liking, change your liking.

Travel can make you a happier American, as well as a citizen of the world. Our Earth is home to seven billion equally precious people. It’s humbling to travel and find that other people don’t have the “American Dream”—they have their own dreams. Europeans like us, but with all due respect, they wouldn’t trade passports.

Thoughtful travel engages us with the world. In tough economic times, it reminds us what is truly important. By broadening perspectives, travel teaches new ways to measure quality of life.

Globetrotting destroys ethnocentricity, helping us understand and appreciate other cultures. Rather than fear the diversity on this planet, celebrate it. Among your most prized souvenirs will be the strands of different cultures you choose to knit into your own character. The world is a cultural yarn shop, and Back Door travelers are weaving the ultimate tapestry. Join in!