Isochrony is a natural expression of the phenomenon of pulse in speech, and describes the tendency for strong stresses to arrange themselves at roughly even intervals; it is the ‘innate pulse’ of spoken language. As I mentioned in my earlier definitions, English is often claimed to be a ‘stress-timed language’, i.e. one where strongly stressed syllables are perceived to be delivered at an approximately constant rate, and where weak syllables will bunch up or spread out to facilitate it. Vowels which land on strong stresses can either elongate or, through a kind of mutual repulsion, command space around them. Weak stresses tend to be treated as being of relatively negligible length, and converge on a broadly uniform, indeterminate short vowel (the ‘schwa’); they are thus able to bunch up as tightly or loosely as they need to within the weak gap between the strong stresses, and so facilitate their relatively even placement.

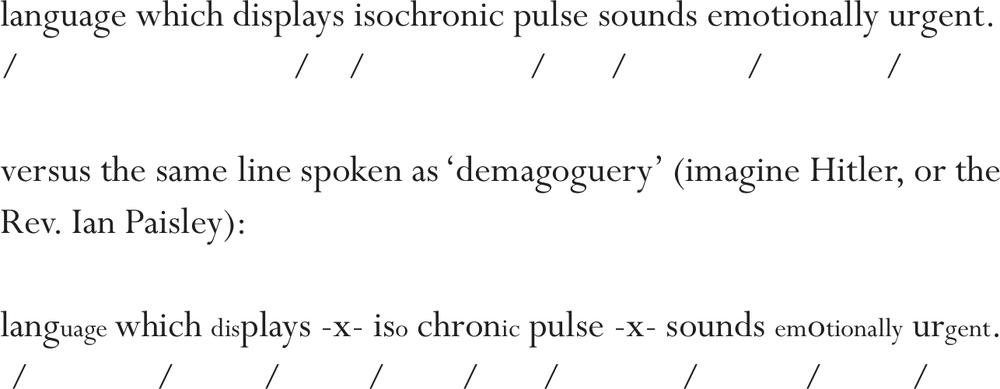

Isochrony is most clearly heard when language is emotionally urgent. Its existence has been rather hard to prove in the lab, and one occasionally hears it written off by phonologists as a psychological projection, which is likely a part-truth. However, the studies I have looked at seem compromised by their not taking into account the regularising effect of high emotion and rhetorical pitch. Verse is generally ‘urgent speech’ of one sort or another, and tends to foreground isochrony even in its non-metrical forms. Crucially for poets, the connection also works inversely: the psychological association is so strong that language which displays isochronic pulse sounds emotionally urgent, regardless of its content.

Consider:

But while isochrony is a clear feature of brainwave, heartbeat, footstep, breath, and so on, its presence in spoken language remains a mere tendency, and it is as much a psychological, listener-projected phenomenon as a feature upon which speech naturally converges. However, all heightened speech – from cries of terror to declarations of love, from barked instructions and political speeches to ‘lecturer’s stress’ (‘This SEEMingly iRRELevant POINT I am MAKing about BYron’s HEADgear is VEry imPORtant’) – will overdetermine the isochronic effect, and introject it heavily as a performative feature. Isochrony is not a rule, but just the linguistic expression of the physical drift towards periodicity that we find in any series of salient events, and a straightforward by-product of physical law.

Isochrony runs through time, but does not measure time. Many natural processes in this particular universe settle down into periodicity, with the same event recurring at even intervals; but this is not yet ‘rhythm’, which is a perceptual phenomenon – and one likely confined to humans, at least on this planet. Isochrony can, however, be considered the ‘wallpaper’ from which rhythmic, metrical template is cut. Like metre, it consists in the alternation of weak placeholders of even duration, and strong positions which mark single events. The passive character of this weak interstitial space is linguistically advantageous in that it allows grammatical function to be demoted to weakly stressed positions of cognitive non-salience, allowing the brain’s live processing to concentrate on lexical content, where strong stress and strong position are aligned.

Presumably, however, the ability to make such differentiations, and perhaps even the very origin of the function-content distinction, derives from the condition of periodicity itself. In other words: what is also alternating in this continuous weak-strong flow is syntagmatic connection and paradigmatic instance – one connecting horizontally, one instantiating vertically. (The axial relationship is strikingly reminiscent of an electromagnetic wave, where two fields, one magnetic and one electrical, oscillate at right angles to one another, inducing each other perpetually through space-time. It could easily be where we ‘got the idea.’)

As urgency increases, the frequency of strong stress increases; at zero-degree, emotionally zombified rhetoric, there are close to no perceptible stresses at all. I overheard a conversation in a bus in Dundee recently of such informational non-import I could not identify a single s-stressed syllable. I believe the statement was to do with milk, and was delivered like a sewing machine. Eh-dinna-ken-if- or-no’-there’s-ony-left-in-the-hoose / Eh-hink-Eck-yased-the-last-o’-it-last-nicht-but-Ah’ll-beh-some-the morn’s-morn-tho’.1 It would scan as x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x. On the same bus a day later, I overheard a woman (of Indian ethnicity, for the record) deliver a far more urgent line to rein in her badly misbehaving child: YOU-WEE-MINK-YOU-COME-OWR-HERE-RICHT-THIS-MEENIT, which has ten consecutive s stresses.

The clear isochronic tendency of emotionally charged speech is one form of ‘proof’ that metrical poetry arises naturally from the language, and merely foregrounds an ever-present pulse. Poetry is often written out of some emotional necessity anyway, and isochrony will be naturally ‘imprinted’ under such conditions. (This explains the identifiable presence of a strong isochronic pulse in free verse.)

Poetry gives explicit expression to this tendency when it makes use of a fixed metrical frame. Its ur-form, its primitive cognitive template, consists of a fixed series of strong positions separated by weak positions, and its subsequent realisation in the form of either light, loose or tight metres. While we generally mark weak and strong stress positions with an x or /, these marks do not ‘represent spoken stresses’. (Metres can be realised by many other material phenomena besides speech.) The w position mark represents a placeholding duration, while the s position mark represents an event, and in poetry these positions are realised by syllables which carry the characteristic of a weak or strong stress. (The point will be developed, but bear in mind for now that a ‘weak’ stress entails a considerably diminished vowel length, ‘strong’ an increased one; for this reason, more than one weakly stressed vowel can inhabit a w placeholding duration, while only one s-stressed vowel can coincide with an s event position.)

Additionally, the kind of isochrony that all poetic lines draw forth – even those of ‘free verse’ – will increase the relative frequency of strong stresses. With an increase in the evenness, number and proximity of those strong stresses, we see an increase in the incidence of consciously processed content words, leading to an increased degree of referentiality in the language itself; this explains poetry’s reputation as vivid, imagistic and ‘invocatory’ speech. No one ever says things quite like ‘On the middle of that quiet floor / sits a fleet of small black ships, / square-rigged, sails furled, motionless, / their spars like burnt match-sticks’2 except in poetic lines. Strong-stress frequency also increases the overall vowel-to-schwa ratio, and potentiates the carriage of much tonal and therefore personal information: accent, origin, ethnicity, emotional state, age, sex, body-size and so on; this is no small factor in the reader’s ability to ‘make the poem their own’. It simply increases the poem’s expressive potential, through expanding that component of speech capable of ‘personalisation’ in its vocal or internalised performance.

Metred verse, through its insistence on both a greater degree of regularity and a higher incidence of regular s-stress syllables than we might encounter in our natural speech, overdetermines all the isochronic effects mentioned earlier. It not only forcefully echoes the sound of urgent speech, regardless of its content, but simultaneously enforces a rhetorical or emotional urgency of delivery, and requests that the poet’s words also ‘step up to the mark’: they had better have something urgent to say if they are to take such a tone with the reader.

The ‘natural metre’ of speech consists primarily (but not exclusively) in a combination of the isochronic rule and the alternate stress rule, discussed shortly. Language already exhibits a strong degree of metricality in its ‘resting state’. Free verse relies only on language’s natural metre, together with the intensified isochrony of heightened speech and the metricalising effects of lineation. Syllabic ‘metres’, while compositionally useful, are oxymorons in English; they do not compel a pulse, and are simple counting systems producing no more metre than, say, regular occurrences of the letter ‘q’, or the evenly spaced names of English regional cheeses. You will hear some individuals claim otherwise, but they are fooling themselves or their ears; Germanic syllables can only be counted consciously, not ‘grooved along to’ instinctively – and even then only by completely mangling the natural prosody of the language to flatten out the difference between weak and strong, so all syllables fall on evenly spaced event positions. Nonetheless I have heard people try to win this point by reading poems aloud in what sounds like an old beta for Stephen Hawking’s voice software. (There is a better argument for the audible syllabic quality of iambic pentameter, but we’ll get to that.)

1 ‘I do not know whether or not there is any left in the house; I think Alex used the last of it last night, but I’ll purchase some tomorrow morning.’ My using an example drawn from dialectal speech may sound patronising, but dialect accommodates the merely phatic exchange (i.e. one whose purpose is more social than informational) far more cheerfully than formal English – hence, frankly, its superior warmth.

2 Elizabeth Bishop, ‘Large Bad Picture’, Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).