Exactly like all complex musical rhythms, any line can be (and generally is) broken down into simpler components of twos and threes, no matter how complex its prosody.1 This might permit the emergence of a metre-type upon which other lines may converge, or allow a complex template to be designed from scratch. All metres are possible with sufficient introjection or projection: any mad variation you like, when accurately repeated, will create an expectation of its further recurrence; the accurate repetition of a caesura, too, can form part of such a template. As I mentioned in discussing the foot, metre-types are overwhelmingly duple or triple, with ‘paeonic’ / xxx types very occasionally cropping up in light 4 × 4 metres. In the above example by John Greenleaf Whittier (two stanzas from a much longer poem, ‘The Ball of Clava’) – we see the unusual trimeter verse-form

In this feminine-ending stanza, we might, if inclined, analyse the lines as follows: iamb/anapaest/amphibrach, x2; [anacrustic w] amphibrach / trochee / trochee, x2. (Note that a foot should not – if it is to have any integrity as a useful concept and analytical tool – cross a clear caesura any more blithely than it would a line-boundary. To analyse the second couplet as anapaest/iamb/amphibrach would be ‘accurate’, but pretty unsympathetic to what was going on.)

Overdetermination describes the degree of convergence which guarantees the identification of a metre-type, and occasionally its strength means that the metre is conjured far more powerfully that it would be in normal compositional or reading practice. This includes more strenuous forms of projection, some of which can loosen and even override such relatively locked aspects of prosody as lexical stress. The important distinction is that, while metrical template is only a lineated series of strong positions and weak placeholders, metre-type can be additionally overdetermined by a number of lines’ sustained convergence on a specific pattern – and then seem to insist on a precisely ordered count of w- and s-syllables. If the syllabic count-pattern is consistently sustained, it may (as in the 10-position i.p. line) be thought of as forming part of the template itself. Looser or tighter verses, however, will simply take a looser or tighter approach to the overdetermination of metre-type without any change to the basic metrical pattern on which they are built, and these relatively loose or tight approaches can also be components of the cognitive template (best thought of, really, as ‘the rhythmic expectations one has of the line’).

For example: trochees are generally not sustained in duple metre, as more poets prefer to retain a syntactic latitude in their composition, and the freedom to begin the line with either a w or s stress. However, we know that trochaic verse can be sustained by strenuously rejecting that latitude, and overdetermining the metre of the line:

By the shores of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis,

Daughter of the Moon, Nokomis.

Dark behind it rose the forest,

Rose the black and gloomy pine-trees.

(HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW,

‘The Song of Hiawatha’)2

to quote a snatch of that estimable trochee-athon. And as some of you will have suspected, Whittier did not write anything called ‘The Ball of Clava’ (an infamous Dundee ‘properism’ heard among the aspirant classes, along with the sport of ‘badmingting’). I made up the garbage of the first verse to overdetermine the metre of the second, so you heard:

However, these lines are from ‘Hiawatha’. Here, because of the overdetermination of the trochaic pattern – which by this point in the poem has great momentum – you would have heard instead:

With the template firmly embedded in our ear, we hear these lines as trochaic; but if had they been the opening lines of the poem, the lexical scansion we would have instinctively made would have proposed a template nowhere near the trochaic regularity of ‘Hiawatha’, and might indeed have been something far closer to the ‘Ball of Clava’. Metre-type, like almost everything else in life, is not intrinsic but determined by contextual forces.

Precedents are crucial. A beginner’s error is to start a metrical poem with a line or stanza in which there is some metrical ambiguity, or in which many variations occur: the template will then take far longer to be confirmed in the ear of the reader – and indeed they may never hear it at all; ‘variations’ are meaningless without a fixed template to vary from.

The only thing keeping these lines from ‘Hiawatha’ trochaic is the reader’s projection. However, while there are a couple of tricks one can use to avoid trochaics getting repetitive – such as commencing lines with two monosyllabic function words, or using the imperative mood – there are too few to give the trochaic line the flexibility it would need to enter the mainstream of compositional practice. Though as soon as it did so, in its sophisticated use it would soon be indistinguishable from the so-called ‘iambic’ line, other than in its feminine endings: as I’ve observed, by ‘iambic’ we almost invariably mean simply ‘duple’. (Trochees are a little unnatural to sustain, and this does seem to give them a rather ‘otherworldly’ or exotic feel; Longfellow’s choice of trochaics here is, of course, really a kind of racist caricature, akin to a composer using a pentatonic melody played in parallel fourths to signify ‘Chinese’. Shakespeare exploits this effectively, though, in his habit of setting the speech of supernatural beings in trochaic metres: ‘Eye of newt, and toe of frog, / Wool of bat, and tongue of dog, / Adder’s fork, and blind-worm’s sting, / Lizard’s leg, and howlet’s wing, / For a charm of powerful trouble, / Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.’4)

An overdetermined metrical rigidity and strength can be achieved not only through the determined repetition of fixed metrical patterns, but also by ‘writing to’ classical forms or their Anglo-Saxon equivalents; writing to song forms (song doubly fixes prosody by attaching an audible quantitative dimension to the vowel); isocolonic patterning (i.e. the repetition of syntactic structure, as seen in the ‘Whittier’ example earlier), and so on. However, this fixity often comes at an expressive price: it simply sounds unnatural, in no small part because it limits the use of the free and subjectively placed suprasegmentals that we associate with the more expressive and dramatic modes of performance.

Metrical variation in strenuously overdetermined metres is oxymoronic, and either extremely difficult or logically impossible to achieve; the line, by definition, requires a far higher degree of projection to be maintained, meaning that syllable count must be pretty rigid, as liberties are likely already being taken with lexical stress. Such lines are very brittle, and sustained more by readerly projection than by the lines’ RSP; the reader will quickly lose the metrical frame if the line makes even a single radical deviation from the expected pattern. Even triple metres can suffer very little variation before they decay into mere natural stress-rhythm, and halfway-house, duple-triple approaches often create the perception of doggerel – at least in the hands of almost everyone but Louis MacNeice, whose metrical success remains something of a cosmic mystery:5

In the top and the front of the bus, eager to meet his fate,

He pressed with foot and mind to gather speed,

Then, when the lights were changing, jumped and hurried,

Though dead on time, to the meeting place agreed,

But there was no one there. He chose to wait.

No one came. He need not perhaps have worried.

(LOUIS MACNEICE, ‘Figure of Eight’)6

If they can stay the right side of contrived artifice, overdetermined strategies can offer some interesting possibilities. They allow for far better analogues of quantitative classical forms than those which attempt to count vowel length (pointlessly: in English, length is certainly present as a feature, but it’s rarely a salient one). ‘Sapphics’, for example, approximate three lines of /x/x/xx/x/x (two trochees, a dactyl, and two trochees) and one of /xx/x (a dactyl and a trochee). Swinburne makes a decent fist of it in ‘Sappho’ (in stark contrast to, say, Auden’s or Bridges’s quantitative experiments), and the template becomes audible after only a few stanzas:

… Saw the white, implacable Aphrodite,

Saw the hair unbound and the feet unsandalled

Shine as fire of sunset on western waters;

Saw the reluctant

Feet, the straining plumes of the doves that drew her,

Looking always, looking with necks reverted,

Back to Lesbos, back to the hills whereunder

Shone Mitylene.

(ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE, ‘Sappho’)7

Though any arbitrarily constructed pattern will work just as well, and – as we’ve seen – may even include caesurae, which can be a metrical effect if (and only if) repeated regularly. Take /xx/ | x///xx (something like: dactyl, catalectic trochee, caesura, bacchius, dactyl, if you’re the sort to care – though I might scan it as an ‘overdetermined light metre’ 4 × 4, i.e. a 4-strong line with variations and a mora taking the place of the caesura, for reasons later explained). These nonsense lines were written in ten seconds flat, so forgive me – but you’ll get the idea:

Give me that knife, you great mad idiot!

Put it away, and kill all wrathfulness …

Set it aside, or take yon blunderbuss

down from the wall, and shoot that rattlesnake.

The ‘success’ of the molossus of ‘great mad id-’ / ‘kill all wrath-’ / ‘take yon blun-’, etc., might appear to suggest that any foot might be conceived of as a non-variant if it can be located in the template, albeit one initially formed by successive identical instances of ‘anomalous’ lines. This would be one way of ‘proving’ the possibility of the true English spondee, which many theorists feel cannot exist (on the principle that if two strong stresses occur together, one must weaken to preserve alternate stress): if a spondee merely realises part of an abstract metrical frame which contains successive strong-stress positions, then it ‘exists’. To ‘disprove’ that, one would have to then argue the illegitimacy of the frame itself, and claim that all frames are, ‘beneath it all’, composed of only alternate w-s patterns. (I might not go quite so far, but would certainly argue that these overdetermined templates nonetheless ride on the tickertape of the endless w-s pattern. But this misses the point: a spondee is a verbally realised foot; if two strong positions occur successively as a part of an overdetermined abstract frame – designate that part of the template a ‘spondee’, by all means; just understand that this points to something which does not exist. But overdetermined templates can encourage the spondee, and spoken words can then realise it. Damn right.)

The closer this kind of patterning dovetails with the 4 × 4 form (as it often does), the more robust it becomes:

High on the shore sat the great god Pan,

While turbidly flow’d the river;

And hack’d and hew’d as a great god can

With his hard bleak steel at the patient reed,

Till there was not a sign of the leaf indeed

To prove it fresh from the river.

He cut it short, did the great god Pan

(How tall it stood in the river!),

Then drew the pith, like the heart of a man,

Steadily from the outside ring,

And notch’d the poor dry empty thing

In holes, as he sat by the river.

(ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING,

‘A Musical Instrument’)8

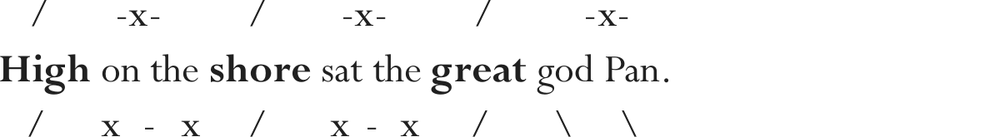

After several verses in which certain lines keep more or less doggedly to the same syllabic pattern, lines which in a single instantiation would sound like a metrical variation now sound as if they are realising part of the form. The first line scans as

– in my system.9 However, suppose that this first epistrophic line had not been repeated in the prominent initial position, and that the whole poem not been written to a fully realised 4-strong template, but instead had read like this:

There! The dark shape of my reckoning –

Near the back door of his caravan,

Raising his left hand and beckoning …

High on the shore sat the great god Pan.

The line last would conceivably be scanned as trimeter, thus:

– A stretch, but the more such triple-rhymed stanzas had preceded the line, the greater the chance of a trimeter being overdetermined. And for my next trick, iambic pentameter:

In the final line, this requires the reader to read the ‘the’ in ‘the shore’ as emphatic /ði/, of course, but it just about works. Contrived as it is, the principle is identical to the one we found at work ensuring ‘Hiawatha’ stayed trochaic.

Similarly, precisely timed overstressing of the sort we find in well-known stagings of Sitwell’s Facade or Auden’s ‘Night Mail’ can overdetermine a metre by taking lexical stress prisoner. In the latter case, the performance converges on the rhythm of Britten’s score through adding the odd mora (a pause-length of about half a w-stressed syllable, here corresponding to a semiquaver rest in the score) between syllables and phonemes to add some quantitative fixing, as well as the use of strictly timed, w-substituting caesurae [-x-] between phrase boundaries.

THIS [:] is the NIGHT[:]mail CROSSing the BOR[:]der, BRINGing [:] the CHEQUE [:] and the POST[:]al ORDer, LETTers for the RICH, [-x-] LETTers for the POOR, [-x-] The SHOP [:] at the CORNer and the GIRL [:] next [:] DOOR.

Any text, however, can be made to fit a metre if lexical stress is ignored:

SIMilARly, PREEciseLEE timed OVerSTRESSing OF the SORT we FIND in WELL-known [switching to triples] STAGings of SITwell’s FaCADE, -x- or AUDen’s Night MAIL -x- can OVerdeTERmine a METre by TAKing lex-EE-cal stress PRISoner.

This is the kind of hellish mangling many song lyrics regularly undergo, through the strategies of vowel shortening, elongation, elision and division, and the splitting of diphthong.10 However, songs have other merits, and we have rewarded them by naturalising their very strange procedures. In contrast, Sitwellian novelties tend to be resisted for the simple reason that their odd metre will quickly become the most memorable thing about them.

1 Unlikely as this sounds, this is an uncontroversial remark in music rhythm analysis.

2 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Poems and Other Writings, ed. J. D. McClatchy (New York: Library of America, 2000).

3 It might have also been easily projected as two 3-stress lines (i.e. catalectic 4-strong) with triple variations, and two lines of an elaborately overdetermined 2-stress line consisting of two ‘third paeons’ [xx/x].

4 I can vouch for the inherently ‘rising’ feel of English, having almost driven myself crazy making and setting an English version of Striggio’s libretto for Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. It meant flipping the polarity of the whole language: English rises, and mostly goes duh DAH. Italian falls, and mostly goes DAH duh – and therefore so does any music written for it; it felt like trying to squeeze a set of spanners into a velvet box made for a dinner-service.

5 Once we have decided to identify such metrical eccentricity as a ‘style’, we will often let it pass. A style is generally regarded as deliberate matter, and not perceived as a form of incompetence; this is surely the correct diagnosis in MacNeice’s case. However, this generosity usually depends on the author’s name – with which comes all their previous poetic success – being firmly attached to the work; whether we would extend that generosity to an anonymised reading very much depends on the reliability of our taste and critical discrimination. I would dare not rely on mine, and for this reason I regard ‘reputation’ as a very useful thing – not, as some do, as the means by which otherwise unpublishable work is smuggled into print by a self-serving cabal.

6 Louis MacNeice, Collected Poems, ed. Peter Macdonald (London: Faber & Faber, 2007).

7 Algernon Charles Swinburne, Selected Poems, ed. L. M. Findlay (New York: Routledge, 2002).

8 Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Selected Poems, ed. Marjorie Stone and Beverly Taylor (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Editions, 2009).

9 One would likely perform a mora after ‘god’; the overdetermined metre-type is triple, but in this foot, the expected consecutive w stresses are met with a single s stress, which is then demoted. This means it also requires some quantitative compensation, hence the mora. I have notated the one-size-fits-all AS pattern on top, not that of the overdetermined template. Arguably a fuller scansion of these metrical curiosities would include the AS pattern and the overdetermined template above the line.

10 This accounts for many a mondegreen, including my own mishearing of ‘Islands in the Stream’ by Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers – lexical stress [/x x x /], but performed something like [/ x / x x] to fit the note-lengths and rhythm of the song – as ‘Ireland’s Industry’. Which I did, bewildered, for years.