Let’s turn now to a more practical application of the ASR. What I’ll call the ‘alternate stress matrix’ is derived from the principle that the ASR preserves some kind of s-w, high-low alternation at every hierarchical level of the metrical template; the mathematical consequence of this statement is that no two stresses can have exactly the same value. What is proposed below is a method of stanzaic analysis, but whether this should be incorporated even into an exhaustive scansion is doubtful. I think it may overcomplicate the exercise pointlessly (the notational complexities are mind-boggling) and we might do best to think of the AS matrix as not contributing to a scansion per se, but providing a separate means of analysing larger structural units and their relative key-falls and rises. However, certain saliences in the pattern may also be compositionally influential, and these might well be worth taking into account when we scan units greater than a line in length.1

The empty form of the line, couplet, or stanza seems to function as a coherent metrical-intonational unit if and only if the cognitive frame of the metrical template is anterior to the poem – that’s to say if the speaker has the form already in their mind as a w-s, ‘duh-dah duh-dah’ pattern before the words have filled it in.2 Above the w-s syllabic level, the AS matrix might seem a purely human projection, and not ‘intrinsic’ to poetic form, let alone language; its existence seems to depend upon our determination to impose it, and then perform it – which we naturally confuse with hearing it ‘actually there’. However without the larger structures the AS matrix describes, poetic form itself would not exist; the matrix might be said to have as much ‘real existence’ as the weak-strong alternation of stress at syllabic level.

To put it another way: w-s syllabic AS is just as much of a projection as AS at any other level. Recursive patterns of AS at higher levels are telling us only about the reality of our own internal auditory and temporal structures, and lines and stanzas are themselves only external projections of this pattern. To repeat the war cry: there is no intrinsicality, and in ascribing qualities to forms, many AS fantasies forget this. This is different from saying the structures created by AS aren’t real: things can be present and manifest without possessing any intrinsic qualities. (I always feel that ‘reality’ is a less troublesome idea than we make it, being merely the category of everything which ‘obtains’.)

The character of AS at the level of syllable, metron and dimetron is predominantly a s-w stress pattern, reflective of the s-w stress patterns of speech. As the units double, however, it takes on a steadily increasing intonational character, reflective of the high-low speech pattern of the intonational phrase. By the time we get to line, distich and strophe, these distinctions are predominantly related to pitch, and better thought of as overall key-falls, not stress differences. This is a slippery idea intuitively understood, as can be heard if you get a group of schoolchildren to ‘duh-dah’ their way through an imaginary two-stanza 4-strong poem. The first stanza will sound something like this:

duh DAH duh DAH duh DAH duh dah

duh DAH duh DAH duh DAH duh dah

duh DAH duh DAH duh DAH duh dah

duh DAH duh DAH duh DAH duh dah

– with the lines themselves falling in pitch, while nonetheless maintaining their alternation: if 4 is high and 1 low, the relative pitch of each line would sound 4,2,3,1. (Phonology has far better systems of notation for real speech, but perversely they’re ill-suited to our crude purposes.) To see the effect this has on a real poem, let’s look at Edna St Vincent Millay’s ‘First Fig’. This is a clear common-metre poem with a single variation (i.e. the lengthening of ‘burns’ in line 1 to accommodate a trochee; an easy enough trick in any dialect like Scots or American with a semi-consonantal ‘r’).

If we remove the w stresses, we can hear the alternations at the level of metron:

Now the dimetron:

Now the line (the arrow is now really indicating pitch contrasts between whole lines):

↑

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

↓

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends –

It gives a lovely light!

… And, for the sake of argument, the tetrastich or strophe (which would obviously only be perceived if the poem was at least two verses long):

↑

‘Heaven bless the babe!’ they said.

‘What queer books she must have read!’

(Love, by whom I was beguiled,

Grant I may not bear a child.)

↓

‘Little does she guess to-day

What the world may be!’ they say.

(Snow, drift deep and cover

Till the spring my murdered lover.)

(EDNA ST VINCENT MILLAY, ‘Humoresque’)4

Because the matrix is conceived of in the mind as a single intonational unit falling from high to low, the first accent of the stanza must be higher than others, and the last the lowest. Within this rule, though, AS must be maintained at all the other levels. As previously stated, the alternation at higher levels of line and above is perceived less as ‘stress’ than as a steady stepped falling, with the ‘key’ of the second unit of any pair lower than the first. This means that the number of height-gradations needed to express all the arrow-falls and rises accurately within any larger unit are exactly the number of s stresses. (e.g. in ‘First Fig’, ‘will’ in line 2 must be higher than ‘night’ in the same line to preserve the dimetronic AS – but lower than ‘candle’ in line 1 to preserve AS at the level of the line, and so on).

AS only works on binary pairs, and many forms do not exactly fit it. The point is controversial, especially when we get to forms which leave large parts of the matrix blank; but because the matrix precedes the poem, the values remain the same regardless of the poem-shape, and the poem is merely ‘plugged in’ to the matrix regardless, in the way than most easily and instinctively fits. For example – in ‘First Fig’ we include the ballad-metre ghost metrons of lines 2 and 4 in our calculations, as their stress value is ‘felt’, if not directly experienced; and so too the ‘missing lines’ of, say, the sestet of an Italian sonnet, where we would still bracket in the matrical values of the non-existent lines 7 and 8 of the distrophe, i.e. the two lines after the sestet. This proposes that asymmetric stanzas are unconsciously measured against a symmetric norm. (Of course this involves buying into the theory that the ASR operates at very high unit levels; but remember it’s a phenomenon that consists – no more, no less – in the strength of its own projection. In other words if I hear it, I hear it. My suspicion is simply that others do too.)

In Millay’s ballad, this leaves us with something like:

If the effect is real, it immediately explains one of the key advantages of ballad metre: the ‘lift’ we get on the last word of the stanza, relative to that of the tetrameter quatrain:

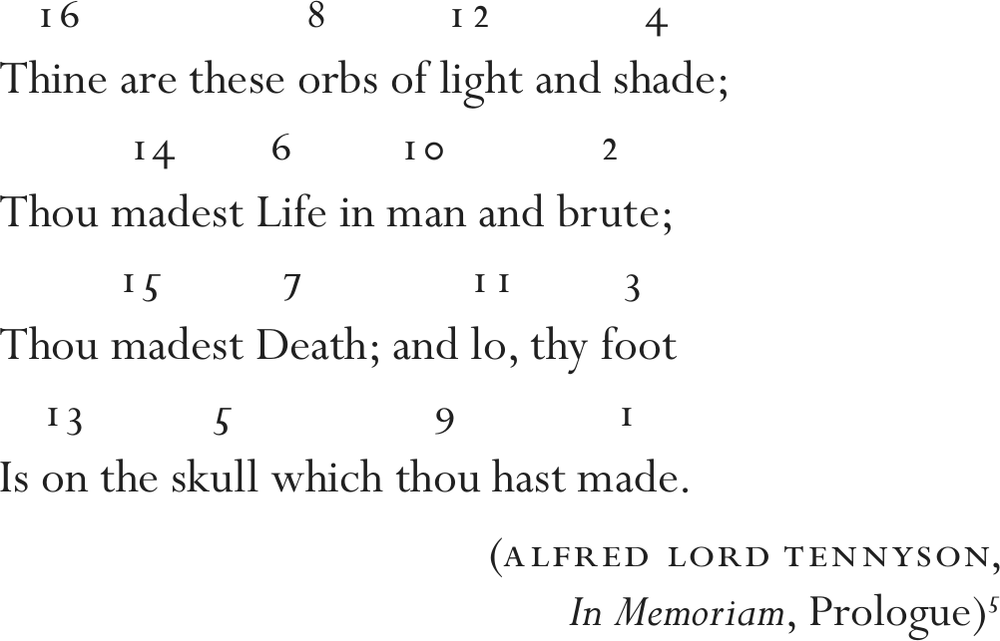

This 16-8-12-4 / 14-6-10-2 /15-7-11-3 /13-5-9-1 frame is common to all 4-strong forms, and allows us to analyse them intonationally: in Keats’ ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’, the last line has a double ghost metron, and the last word of each stanza ends on a note we may describe as low and neutrally flat, a bleak effect frequently reinforced in the poem by a strong lexical stress in a weak position on the penultimate word (the effect is repeated often enough for it to become an overdetermining part of the metrical template) – as well as, of course, the line’s sense:

This effect will be heard over the longest units that can be felt as a single intonational phrase, but it is also a product of other over-determining factors, with versification and syntax prime among them. If lines are written in stanzas which coincide with syntactic closure, AS across longer units will be likely be performed more emphatically.

So we see a complex pattern proposed, where each successively larger binary unit will effectively contribute towards a greater perceived contrast between high- and low-numbered stresses. The upper limit to the influence of these larger units is simply whatever can be held in the reader’s mind as a binary ‘matrical expectation’; if the reader can feel the alternation of the strophic unit, they will likely hear and perform some degree of intonational differentiation between them. However the influence of each higher unit is successively weakened, and contributes less and less to the individual vowel stress (meaning that the true scale is likely to be logarithmic, not smoothly numeric). Beyond the level of two distrophes (i.e. sonnet length + 2 lines) I suspect its prosodic strength is minimal, and at this level we can declare the influence of AS more or less negligible.

1 The basic idea is not particularly original; discussion of the principle can be found in various generative theorists, as well as Cureton et al. I stumbled on the idea independently many years ago while I was involved in more youthful Kabbalistic researches: I was trying to discover whether there was an optimal place where ‘key terms’ in a poem might be buried or foregrounded for subliminal effect. As much as this sounds like a piece of neuro-linguistic programming nonsense, I still think there may be something in it, and will discuss the matter later.

2 The line, stanza and poem itself – if conceived of by the poet as coincident with the distinct units of speech – tend to exhibit just the high-to-low, fast-to-slow syllabic pattern you would expect, with a particular drag being enacted in the final line, one often experienced as metrically ‘heavy’ even in free verse. This often semi-deliberate reversion to an evenly stressed (or even overtly metrical) line at the end of the poem can also act as a kind of retrospective assurance that what the reader had just experienced was, in fact, a piece of syntactically and emotionally coherent speech, lest they were still unconvinced.

3 Edna St Vincent Millay, Collected Poems, ed. Norma Millay (New York: HarperPerennial, 2011).

4 Edna St Vincent Millay, Collected Poems, ed. Norma Millay (New York: HarperPerennial, 2011).

5 Alfred Lord Tennyson, In Memoriam, ed. Eric Irving Gray (New York: W. W. Norton, 2004).