I have been rather breezy about all those numbers, and we should take a closer look at them. We’ve seen that within the matrix, self-similar patterns of alternation occur within any unit or sub-unit, and that the second of any unit-pair must always fall in relation to the first. Individual stresses can be given a numerical value, summing the weak and strong values of all the various levels to which they simultaneously belong, i.e. where they occur within the pattern of alternating metron, dimetron, stich, distich, strophe and distrophe (which I’d claim is their reasonable limit). Below is an analysis of the first stanza of Auden’s ‘The Fall of Rome’,1 but any 4-strong or common metre stanza would do (as we’ll soon see, this is code for ‘any metrical poem not in i.p.’). The smaller the unit, the stronger its influence; this is why most metrical scansions only take account of syllable stress, where the AS pattern exerts its greatest pull. This is the same as saying that the larger the unit, the less power it has; as we move through the higher units, their strength-conferring influence over the individual syllable is halved until it becomes negligible.

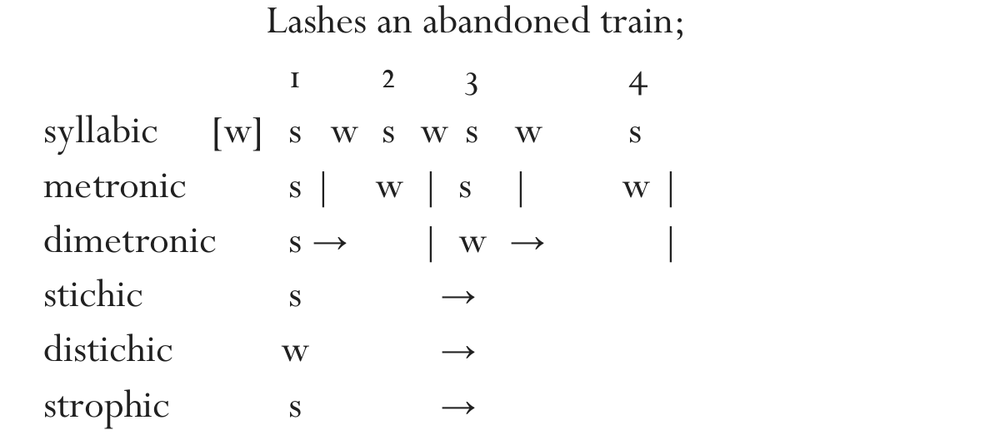

Before we try to find the most sensible way to notate this, I’ll first make a note of the s-w patterns of paired units at every level in a four-line stanza (which for the sake of argument we’ll consider as the first of a pair of stanzas, hence the ‘strophic’ row). In this pair of stanzas, we would have 32 s stresses, all of which would be differentiated in value. The forward arrow indicates that the given s or w value extends to the unit division or end of the unit.

(Note that ‘metronic’, ‘stichic’ etc. in the column below refer to contrasting pairs of those units. The procedure is cognate with the ‘metrical grid’ in the field of metrical phonology, a way of displaying hierarchic levels of syllabic salience.)

line 1

line 2

line 3

One can immediately see that the relative strength of a stress can be given by summing the number of strongs in each column. As I’ve said, the influence of the s on the individual s stress syllable will diminish as the units increase in size. All s stresses at the syllabic level are equal, so we can attach a base value of 1. Let’s assume a two-stanza poem of 4-strong metre. Let’s arbitrarily assume strength is halved as each level doubles in size, and that w-marked spaces counts as 0. So an s at the metronic level is 16; at the dimetronic, 8; at the stichic, 4; and so on. The first stress would then have an s-number of 1 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 32. The third stress in line 3 would be 1 + 16 + 0 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 22; the weakest stress in the stanza would be the fourth stress in the fourth line, with 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 1 = 2. The lowest, 1-value stress in this two-stanza form would be the final stress in our second stanza, strophically marked 0. Each time a level is added – let’s say we wished to project a distrophic frame of alternating eight-line stanzas – the values would double, with 32 as the metronic s, 16 as dimetronic s, etc. (Note that a four-stanza poem in tetrameter quatrains analysed in this way could arguable have 64 degrees of stress: this is borderline absurd, and is likely to have little relation to its actual spoken delivery. However, this kind of analysis is a highly useful tool in identifying extreme and median values, and any given poem’s deviation from them.)

All this leaves us with a distrophic matrix of:

| 32 | 16 | 24 | 8 | |

| 28 | 12 | 20 | 4 | |

| 30 | 14 | 22 | 6 | |

| 26 | 10 | 18 | 2 | |

| 31 | 15 | 23 | 7 | |

| 27 | 11 | 19 | 3 | |

| 29 | 13 | 21 | 5 | |

| 25 | 9 | 17 | 1 |

And if we plug in the first stanza, we get:

Remember that while AS at unit levels below the stichic is strong-weak in character, for stichic and above it will pull towards high-low, with the quality of pitch being the dominant character of its ‘strong stress’. These summed values convey nothing of that. We might try something like this:

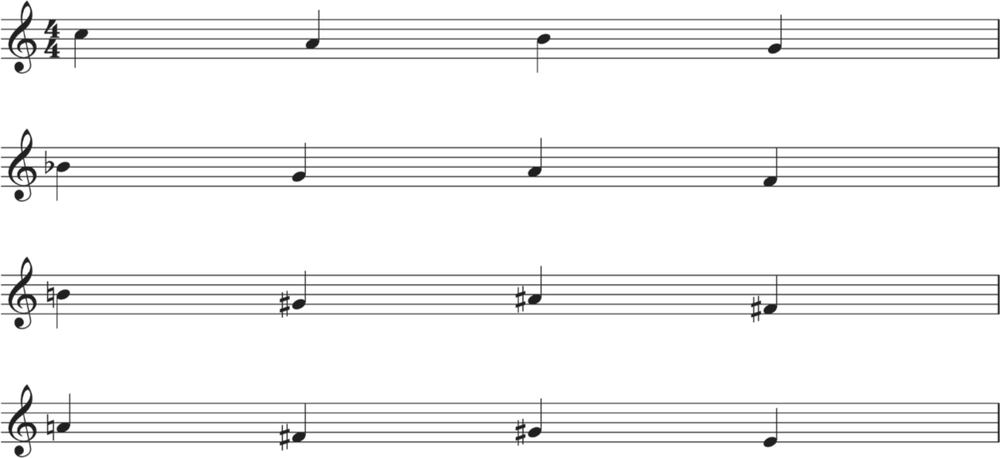

– where the metronic and dimetronic strongs are placed above the line, and stichic and above alongside it; but this is hardly an improvement, and as a performance blueprint, worse than useless. The problem is relatively simple, though: since the AS matrix at the level below stichic does not change from one line to the next, all we are really seeking to represent is the relative height of an intonational contour – essentially, a melody transposed into different keys. While the representation below does not have the granularity of our numerical representation, it’s more sympathetic to the general idea:

And if we assume the schwas too short to carry perceptible information, the tonal information might even be caricatured as this kind of thing:

Alas both methods are impractical and do not even provide a way of supplying ‘fake’ precision, nor of dovetailing with a conventional metrical scansion. But if the numerical AS matrix is taken at face value with its serious limitations acknowledged, I believe it may be a useful tool for identifying hidden features of stress. So when we use the AS matrix in metrical analysis, I’ll use the numerical system, identifying it with its appropriate matrical frame. For reference, these are:2

line matrix in 4-strong: 4-2-3-1

line matrix in i.p.: 6-3-5-2-4-[1]

distichic matrix in 4-strong:

| 8 | 4 | 6 | 2 | |||

| 7 | 3 | 5 | 1 | |||

| distichic matrix in i.p.: | ||||||

| 12 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 8 | [2] | |

| 11 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 7 | [1] | |

| strophic matrix in 4-strong: | ||||||

| 16 | 8 | 12 | 4 | |||

| 14 | 6 | 10 | 2 | |||

| 15 | 7 | 11 | 3 | |||

| 13 | 5 | 9 | 1 | |||

| strophic matrix in i.p.: | ||||||

| 24 | 12 | 20 | 8 | 16 | [4] | |

| 22 | 10 | 18 | 6 | 14 | [2] | |

| 23 | 11 | 19 | 7 | 15 | [3] | |

| 21 | 9 | 17 | 5 | 13 | [1] | |

| distrophic matrix in 4-strong: | ||||||

| 32 | 16 | 24 | 8 | |||

| 28 | 12 | 20 | 4 | |||

| 30 | 14 | 22 | 6 | |||

| 26 | 10 | 18 | 2 | |||

| 31 | 15 | 23 | 7 | |||

| 27 | 11 | 19 | 3 | |||

| 29 | 14 | 21 | 5 | |||

| 25 | 9 | 17 | 1 | |||

| distrophic matrix in i.p.: | ||||||

| 48 | 24 | 40 | 16 | 32 | [8] | |

| 44 | 20 | 36 | 12 | 28 | [4] | |

| 46 | 22 | 38 | 14 | 30 | [6] | |

| 42 | 18 | 34 | 10 | 26 | [2] | |

| 47 | 23 | 39 | 15 | 31 | [7] | |

| 43 | 19 | 35 | 11 | 27 | [3] | |

| 45 | 21 | 37 | 13 | 29 | [5] | |

| 41 | 17 | 33 | 9 | 25 | [1] | |

I refer to the highest value in any given matrix as zenith, the lowest as nadir.

1 W. H. Auden, Collected Poems (London: Faber & Faber, 2007).

2 Note that despite the ghost metron being something of a fiction in i.p. – it is an indeterminate pause only counted under specific modal circumstances – it’s a necessary one, if we are going to apply accurate AS numerical values in this way. I’ve included here the values for the AS matrix in i.p. at levels beyond the stichic, even though I think their existence is highly moot; I discuss a radical alternative in a future chapter. Much depends on the stanza form in which i.p. appears: while sonnets imply a clear hierarchical binary frame at the level of line, distich and tetrastich which will at least be felt as a pattern of alternating key-fall – generally speaking, lumps of blank verse will generate little sense of alternation above the stichic. Therefore one might say that larger AS matrices might conceivably be applied to sonnets, but not to blank verse. However, I will later argue that the more common reason for AS emerging at higher units in i.p. is down to i.p. entering a lyric mode in its stanzaic forms, one with a radically different metrical template.