One of the more misleading bromides one still hears is that ‘it is just as hard to write good free verse as good formal verse’. Since the only sensible purpose of formal rule is to prevent the poet from writing the dull or stupid thing they’d intended to write and force them to write something surprising or intelligent instead – this statement cannot be true.1 As terrible a soundbite as it makes, what would be truer to say is that ‘free verse which compensates for the lack of resistance inherent in its formal rules through the introduction of other kinds of procedural resistance … is as hard to write as formal verse’. (Also true is ‘bad free verse is just as easy to write as bad formal verse’.) If this resistance is not in place, in whatever form – the poet is indeed making it easier for themselves. If the goal of both formal and free verse is natural, original, memorable and felicitous expression, then the method with the most built-in resistance is going to be straightforwardly ‘harder’ to write. With the best will in the world, poets cannot always rely in their own good taste, vigilance and quality control as sources of formal resistance. A few, however, clearly can; though those poets – James Wright and Sylvia Plath come immediately to mind – were often meticulous in their early formal training.

In order to make the ‘free’ game worth playing, most decent poets will replace a formal rule for a compositional one. But this is a risk: if that rule provides too little resistance, they might put the ease and fluency with which they write down to nothing their own uncommon skill and artistic vision. Indeed that may be the case; but formal resistance – in the shape, say, of metrical pattern, rhyme or form – performs the useful service of reminding most of us we are not geniuses. Poets who believe themselves to be so tend to burden their poetic practice with very little formal inconvenience of the kind that would challenge this conceit of themselves. (See, for example, the late work of Ezra Pound or Ted Hughes. I once heard of a notoriously prolific poet who was asked the secret of his remarkable productivity: he answered, unsmilingly, ‘I have a very fertile imagination.’ There are also a number of fluent versifiers who imagine themselves great masters of the poetic art on account of their mere facility; but there, the problem is usually the absence of the various kinds of non-formal resistance that make a good poem, mainly a commitment to original phrasemaking and truth-telling, and to the sophisticated, parallel integration of the poem’s elements.) Yes, ‘no verse is free for the man who wants to do a good job’, but good jobs are guaranteed by checks, procedures and gold standards which make the bad ones easy to spot.

Outside of its historically specific sense of Laforgueian vers libre, ‘free verse’ is a meaningless term, and ‘freedom’ is as much a disease of degree as ‘formality’. ‘Free’ latitudes may be taken with metre, line, stanza, rhyme-scheme and so on; the absurdity of the phrase is clear when one posits a verse free from all those ‘strictures’. What’s required is neutral description, and a first step towards this would be abandoning the word ‘free’ altogether: the word ‘freedom’ has positive associations that bad poems do not deserve, and confers on these poems a kind of fuzzy, undeserved merit. Nor is ‘free’ metre in any way analogous to loose or light metre, since its composition is often more complex than tight formal metre. For now, let’s take free verse as meaning ‘unrhymed verse which demonstrates no adherence to a metrical pattern’; but since we’re focused solely on metre here, there’s no reason not to talk of a poem as written in ‘free metre’.2 There is a great deal to say on the subject of free verse, but most of it is beyond the scope of this book. However, the purely prosodic implications of free verse are not complex, and nor are its rules substantially different from those we apply to light-metre verse.

The most significant feature of free verse ‘prosody’ – the inverted commas are not placed sarcastically but to acknowledge the limited usefulness of the word here – is line-end and phrase boundary coincidence or non-coincidence. Enjambment is a far more significant gesture in free verse than in formal verse, for one simple reason: the reader intuitively knows that the poet, in the absence of any visible or audible formal scheme of regular lines that might drive against the naturally loose rhythm of her phrases, could easily have broken the line at its most natural point, the phrase boundary – and has deliberately chosen not to. There is no frame to blame, as it were. (The deliberateness of the gesture also exaggerates any metatextual ‘play’ on the teleuton.) This feature can be analysed with the same cline we used when discussing line endings, on a scale of least-to-most disruptive.

Claims for the metrical versatility of this crucial feature have been badly overstated (Charles O. Hartmann’s otherwise highly useful book Free Verse exaggerates its versatility to the point of ludicrousness), though perhaps understandably so, since in free verse it represents the primary and often sole locus of expressive tension between frame and speech. However, because of the line-break’s expressly wilful positioning, it encourages the reading of the last lexical stress in the line as the nuclear stress, whether it is or is not – and for this reason we often see an exquisite lingering over the teleuton that is quite impossible to replicate in formal verse. When combined with free verse’s other secret weapon – the flexibility of the hiatus, which permits the introduction of variable silences against the median length of the poem’s lines (as well as, no doubt, the three-second frame) – this terminal ‘lingering’ can become a procedurally distinct and subtle tool of emphasis:

And everything is gone, the body is gone

completely under, gone, entirely gone.

The upper darkness is heavy as the lower,

between them the little ship [ ]

is gone [ ]

she is gone. [ ]

(D. H. LAWRENCE, ‘The Ship of Death’)3

Many examples of free verse seem in the grip of unconsciously introjected templates, principally the ur-form of the 4-strong line; at the very least the three-second rule certainly seems to influence the median line length itself:

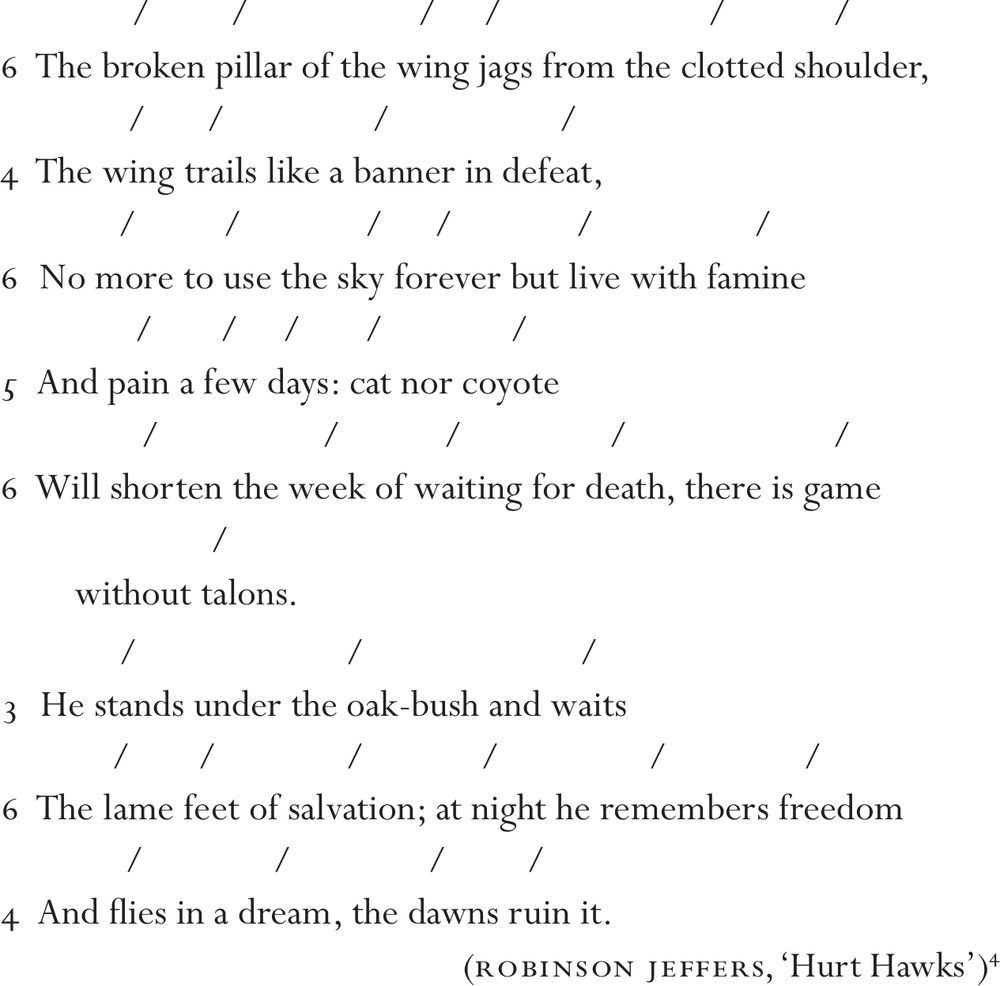

Were we to examine the whole of ‘Hurt Hawks’, we’d see that the strong stresses work out at a rough mean of five per line, suggesting a strong ‘auditory present’ influence (the alternating line lengths might also put one in mind of common metre).

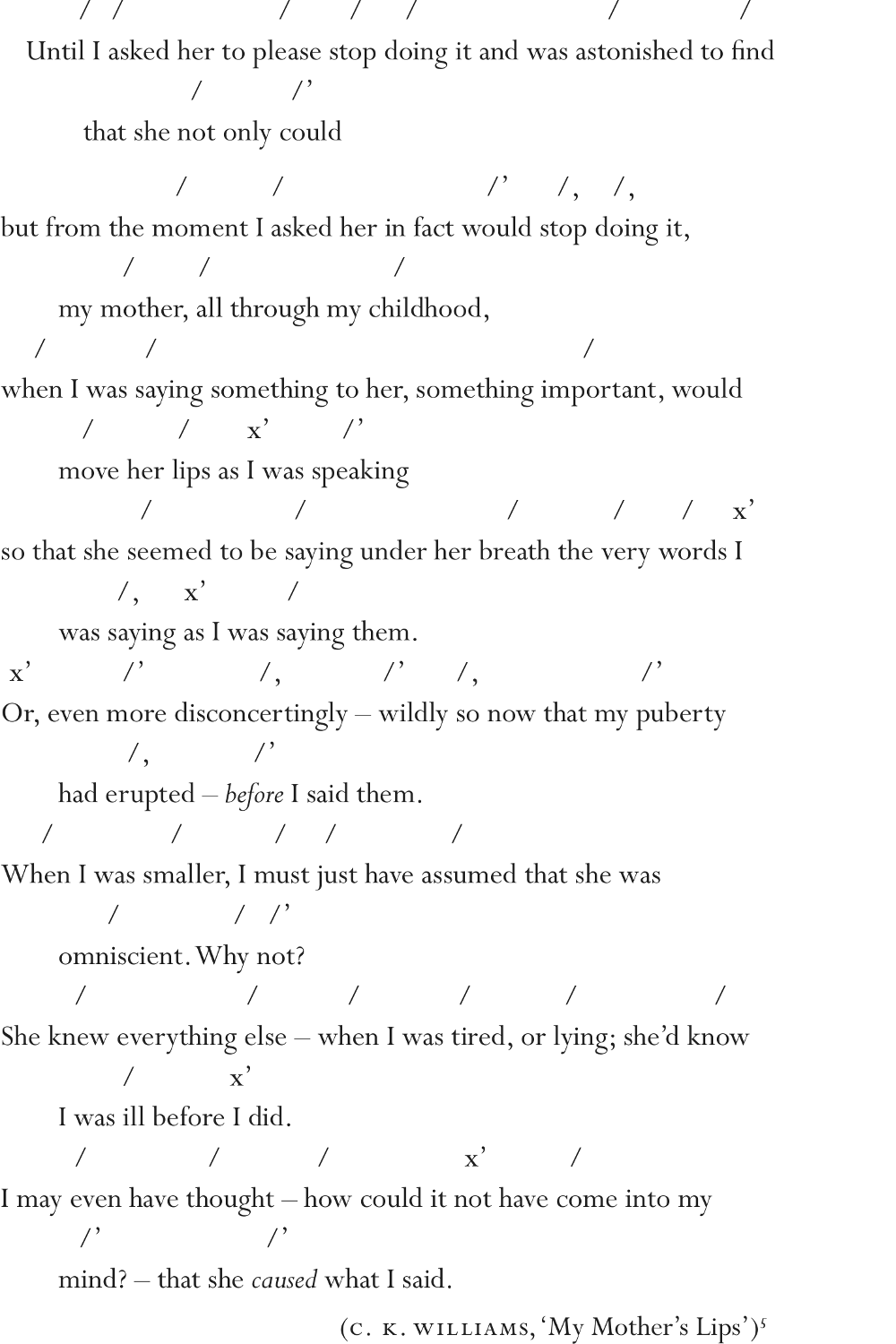

There is absolutely no point in making even a lexical stress analysis of a long free metre line, as speed increases schwa-count considerably, and under such circumstances sense is parsed more at the level of phrase-unit, while individual words demote much of their content to w-stressed function. Far better to immediately make a sense-stress analysis (we haven’t yet looked at this procedure in any detail, but for now it will suffice to know that [’] or [,] after an x or / represents an intonational accent or de-accent derived from semantic context, and can be counted as prosodically equivalent to a strong or weak stress respectively, regardless of the mark it follows):

(Note how the long, function-heavy line accounts for the ease with which semantically determined accent and de-accent can be applied: for example in line 2 ‘… would stop doing it’, we can unthinkingly promote ‘would’ to emphatic content, and drop ‘stop doing it’ to de-accented anaphora.) We immediately note several features: the surprisingly regular number of marked stresses per line (between 7 and 9 here, although one could very easily give just as plausible scansions which varied them a great deal more); the near-organisational force of the terminal NS; and the tendency for high accent to demand an immediate fall on an adjacent stress (more, perhaps, through the need to achieve its own contrastive salience than any application of the ASR, which is just how it would feature in conversational speech).6

1 As for form’s alleged ‘constraints’: ‘Form is a straitjacket the way a straitjacket was a straitjacket for Houdini’ – Paul Muldoon.

2 It is absurd to subject to a metrical scansion free verse which has not been deliberately composed to a metrical frame. This is a bit like scoring a boxer on the aesthetic quality of his footwork. Beyond average phrase and sentence length, etc., the only rules in force under such circumstances are the same as those in play with any random chunk of language which has been lineated: (a) the three-second rule (b) isochrony, tightened under the three-second rule (c) and any unconsciously projected metrical frame.

3 D. H. Lawrence, The Complete Poems of D. H. Lawrence (Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 2002).

4 Robinson Jeffers, The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, ed. Tim Hunt (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001).

5 C. K. Williams, Collected Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006).

6 One immediately suspects the presence of an unconscious 2 × 4 template. Is the long line frequently just an ‘accentual fourteener’, or a 2 × 4 line? Try reading Williams’s poem against a triple-metre fourteener / 8-strong template; the results, while far from conclusive, show far more convergence than you might expect, e.g.: When I was smaller, I must just have assumed that she was omniscient. Why [xx] not?