I have, to this point, been discussing i.p. in its dramatic mode – one which most poets and readers will inhabit by default; the qualification ‘dramatic’ may even seem redundant. What follows is an attempt to show that the 5-metron i.p. line is capable of sustaining two different metrical templates, which are themselves aspects of two modes of performance, namely the dramatic and the lyric. (For any lay readers still with me: I should make it clear that my remarks on the alternative template of lyric i.p. are resolutely non-mainstream.)

Dramatic i.p. and the 10-position line

Dramatic loose i.p. is the ‘virtuosic’ poetic line par excellence (its template is still best intuited in the late work of Shakespeare, and perhaps most effectively contrasted with the tight i.p. of his earliest work). Its sophistications arise from the simultaneous management of two superimposed templates, the 10-position and the 5-metron, which between them allow for far greater prosodic complexity than other single templates. While this is partly predicated on their being realised by a sophisticated reader, the 10-position template is primarily introjected, which is to say it is a conscious compositional technique that produces different kinds of statement than would AS alone; it is therefore a line whose effects need not depend on 10-position projection in order to be felt (indeed, excessive projection would be counterproductive). The poet in English who employs the 10-position template must deal with an underlying and non-negotiable AS. The 10-position, semi-syllabic ‘feel’ is maintained through the partial conversion of weaker to stronger stresses and stronger to weaker, i.e. of duration-positions to event-positions, and (to a lesser degree) event-positions to duration-positions. While weak durational positions rise towards the status of timed syllabic event, it remains an inferior one, one which still easily allows for perceptible AS when the syllable is realised. Despite its name, the 10-position line need not wholly overdetermine the syllable count, and a modest degree of variation in the number of w stresses found in the weak placeholders is common. Mostly, however, its variations come from the fact that its frame makes the demotion of every strong syllable and the promotion of every weak syllable far easier than would a purely AS template; 10-position actively proposes expressive variation in the line.

It is my impression that since the 10-position line affords the poet the latitude to strengthen w or weaken s, their dramatic and self-dramatising tendencies are easily indulged: the weak invariably rises more than the strong falls, which is to say there is a net increase of event-presence and stress-strength overall, and a concomitant increase in content, vowel length, line length, pitch, declamatory tone and overall drama. An active poet–reader collusion will therefore help sustain it, though what is projected by the sympathetic reader is less a template and more a mode of performance. (In theory, the line could just as easily accommodate understatement, through the consistent demotion of content to function – but such an inclination tends not to be very common within the poetic community.)

The loose i.p. line is delicately balanced. While 10-position actively requires a process of compositional introjection, the frequent presence of an inflexibly projected, 5-metron AS template (e.g. its delivery by a tone-deaf actor) means the 10-position effect – if not actively embedded in the language itself – can be lost, and the line can flip to tight, rum-te-tum syllabotonic i.p., incapable of supporting the kind of variation the sophisticated 10-position line proposes: think of the surely superior ‘WAS it the PROUD FULL SAIL of HIS GREAT VERSE’ versus the lame ‘Was IT the PROUD full SAIL of HIS great VERSE’. The 10-position line demands either a readership sophisticated enough to allow for this new freedom in the 5-metron line or, failing that, one so ignorant of the 5-metron line that they simply treat it as chopped speech (rather ironically, this will often do far less damage to the line than projecting AS too boldly, though with enough projected ignorance, loose i.p. can quickly degrade to light i.p. speech-rhythm). But the point is worth repeating: the introjection of the 10-position line in effect potentiates the possible promotion and demotion of every syllable, thus greatly increasing poetry’s metrical instability – and so its expressive potential and capacity for individual interpretation.

But let’s not overstate the case. While finding in

Oh it was strong and bold and terse,

The proud full sail of his great verse

the variation

Oh it was strong and bold and terse,

the PROUD FULL SAIL of HIS GREAT VERSE

– is by no means impossible, sustaining such tension over a rigid AS frame like loose 4-strong is far more difficult than it would be in blank verse or rhymed, 10-position i.p. couplets. (The variation above is only possible through a ‘speech-strong’ reading, one which favours sense stress over metrical stress, and this will be explained in detail later. Such speech-strong interpretations are far easier to make when aided by the 10-position frame.)

Let’s look at a passage of loose i.p.:

If, as I suspect, Lowell was also ‘feeling’ the line in ten positions, what has changed by his superimposition of this decimal template over the familiar AS pattern? The difference is inevitably subtle, but I think it is present. Yes, we still see a tight coincidence of s-event to even number, maintaining the AS; and with the obvious exception of ‘Dionysian’, we see a strong nuclear stress to high s-position correspondence within the AS template (the syllable at position 10 coincides with a 4 on the AS matrix for i.p.). However, I would claim that with a 10-position ‘awareness’, the AS is somewhat less insistent, and that the independent integrity of the individual line – and that of the statement it makes it – has strengthened considerably as a result of the stronger bound limits of the 10-position template; Lowell’s phrasemaking seems more boldly monolineal than ever (it’s significant that elsewhere Lowell’s inclination is often not to vary merely through caesura, but by actually breaking the i.p. line into two lines). As to the increased level of content realised by s-potentiated w stresses, and the richer variety of interpretations this might subsequently introduce … While I may perceive that this has indeed occurred, I admit it is largely subjective. It is vitally important to bear in mind that articulating the effect of the 10-position template on a line is going to be roughly as hard as trying to nail down the ‘definition’ of a single phonestheme. It is less a slippery concept than a concept defined by its own slipperiness – in this case because all 10-position composition does is potentiate more interpretative variation, or a kind of ‘prosodic connotation’, partly through its cognitive fudging of s and w, content and function, and the operation of paradigm and syntagm. If we again take the line

Under a ‘normal’, tight i.p. scansion, we do little more than line up metrical pattern and speech and see where they agree or disagree. However, with the introduction of the 10-position frame, we are negotiating between

in broad daylight her gilded bed-posts shine,

and the neutral, digital, metronomic ‘Dalek’ stress of

in – broad – day – light – her – gild – ed – bed – posts – shine

Obviously variations like ‘daylight’ will be eased and aided by the blanket, near-syllabic neutrality of 10-position, but the content-syllables ‘light’ and ‘posts’ could easily find themselves performed with extra vowel-quality, enough to push ‘daylight’ and ‘bedposts’ further towards spondee; furthermore, ‘in’ might find itself quietly promoted to a slightly more emphatic role, emphasising the contrast with the night the couple have just seen out, and during which the golden bed was dim. The overall effect will be to increase the perception of content, and so of significant information.

Let’s now look at a very different example with only two content words:

The i.p. frame will attempt to draw five syllables from ‘Dionysian’ here anyway (elsewhere the word could easily be shrunk to a three syllables by making it three monophthongs, as in the i.p. line ‘their crazed Dionysian revelries’, where we would say ‘Die-nize-yin’, and stress the word x/x); but 10-position asks for the syllabic segmentation of the word into Di-o-ny-si-an more strongly than does the mere AS i.p. frame, giving the word great length and prominence. It is also an effect of 10-position to make polysyllabic classical lexis sing rather better in English, by introducing a very light version of its own quantitative scansion (see ‘magnolia’ earlier). For this reason a poet using 10-position loose i.p. is also, I’d propose, far less bound by the old ‘Anglo-Saxon default’ in their choice of lexis. Polysyllabism is accommodated in i.p. by more than just having a longer line to work with: 10-position makes polysyllabism lyric. Because of the slightly evened-out spacing of all syllables, schwa has more time to take on a little of the colour of its vowel. All this has consequences for the not only the lexis poets are inclined to employ in i.p but also for readers: it will require a more sophisticated and educated audience to understand it.

Readers are well within their rights to choose not to enact these potentiated variations, however, and one should not lose track of the fact that they are merely that: potentiated. Let’s look at another example:

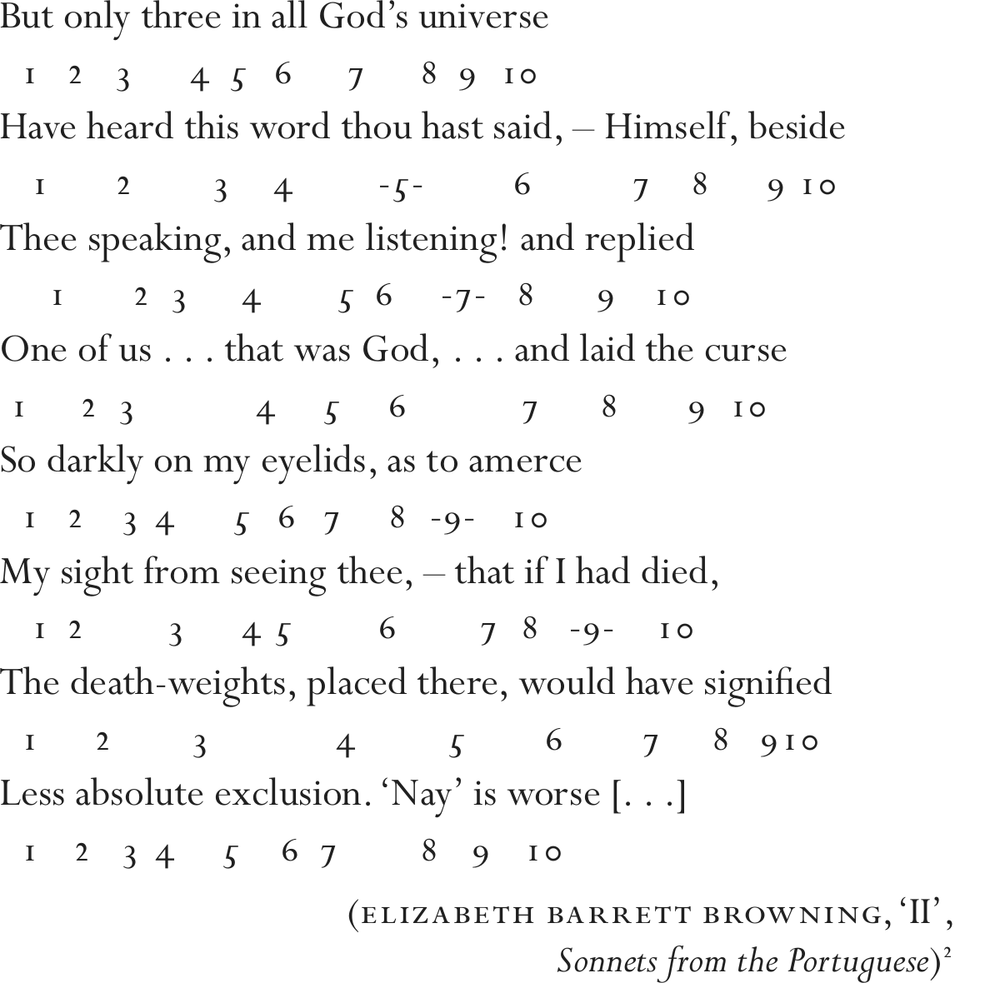

Do the odd-numbered syllables gain any strength through the poet’s introjection of the 10-position template? My own feeling is that they do – sometimes smoothing out what would usually be felt as tension, i.e. as promotion or demotion, to a more direct stress (‘But only three in all God’s universe’); sometimes lyrically drawing out the length of polysyllabic words (in ‘Less absolute exclusion’ we might hear the second word as a little closer to ab-so-loot than we would in other AS or conversational frames, where the last two syllables are mere schwa; ditto ‘ehx-cloo-zhuhn’); sometimes raising phrases more easily to spondee (‘placed there’); sometimes raising a run of functional schwa to something far more emphatic and evenly stressed (‘that if I had died’); sometimes introducing a delicious instability to the phrase (‘One of us … that was God …), and so on; though I freely admit the existence of these effects also depends, at least in part, on my own projection. Nonetheless I believe that the 10-position frame must also have aided the composition of these lines, and the richly tensive possibilities they propose, possibilities that I am then able to explore as a reader.

Some corollaries of the 10-position line

To summarise the differences between tight, light and loose i.p.: tight i.p is not functionally 10-position; it is introjected and projected as a syllabically overdetermined 5-metron AS line and so has a very high degree of convergence. Light i.p. is not 10-position either, as it returns the weak odd-numbered stresses to durational placeholders, where weak syllables might be more freely placed or removed (although because i.p. has no ‘Dolnik’ form it can swiftly degrade into McGonagallesque unmetricality). 10-position i.p. is the definition of sophisticated loose i.p.; but it will remain poorly understood until it is accepted that its essence is its very instability, since tension is written deep into its template – consisting as it does of the superimposition of two metrical templates. ‘Loose i.p.’ contains both syllabotonic and syllabic schemes.

Let’s work out the consequences of this assertion a little more carefully, because they are thoroughly strange. If we assume that the 10-position introjection is at least a compositional reality, then there are several interesting corollaries. In order to make it a 10-position line countable, we need two things: a boldly circumscribed unit that can be apprehended as such, and a flattening out of w-s alternation. This leads to a less pronounced distinction between function and content, the latter promoted and the former (slightly) demoted. To some extent their cognitive roles move far closer to being, if not interchangeable, in flux. It will generally require more cognitive processing than the 4-strong line, because of the relative salience of each syllable. The line is therefore information-heavy, and so better designed for art-speech, not folk-song.

Furthermore, if the Gestalt of the line is strongly reinforced so that the template can be apprehended as a whole (this overdetermination is necessary simply because it’s an alien concept, being a syllabic template in a stress-timed language), it becomes monadic, and – unlike 4-strong – does not imply hierarchical structure (though sometimes we can some see explicit stanzaic overdetermination). This makes it more attractive to and accommodating of independent statement and perception. It may also point to 10-position i.p. being essentially monostichic, where the hiatus is more a terminal or at least indeterminate space than the interstitial gap it is after, say, the second line in common metre; this would explain enjambment in i.p. being far more confusing than its merely odd-numbered strong-stress nature would imply (something we can see from the number of miscounts that occur in run-on lines).

However, if the i.p. line does include the ghost metron in its template – I would say the tight i.p. template probably does – it follows that it can only exist if a second line is anticipated. This means that, while AS never really ‘gets going’ in i.p., there may be some grounds for at least considering tight i.p. a fundamentally distichic form, with the heroic and closed couplets its most natural variations.3 (By contrast, in loose i.p. AS will function less strongly at the sublineal level, since the 10-position template make w-s difference less pronounced, and also at the lineal level, since the line itself tends towards the monadic. Higher-level AS is felt only when the line can be heard as a rising and falling unit, and this effect is generally the preserve of stanzaic tight i.p. (Even then, its limits are probably reached quite swiftly, and I doubt they can extend beyond sonnet length.)

As I’ve mentioned, dramatic i.p. defines itself in opposition to 4-strong, and the 10-position template emphasises that while 4-strong has the heart of a tonic/accentual line, i.p. is contrastively at least part-syllabic. To a degree, 4-strong introjects an accentual template, and 10-position i.p. a syllabic one. The reality of loose i.p. is that it tends to seek a middle ground, and is both an AS template and a 10-position one. Any syllable in loose i.p. is, by birthright, a mixture of timed placeholder and durational event. This surely has the capacity to lend the loose i.p. line some additional dynamism, as well as dragging the line decisively towards, if not a quantitative prosody, then at least a rather French one (as it likely fell on the ears of an educated Elizabethan audience). It is additionally capable of ‘lyricising’ the polysyllable, for the reasons explained earlier, and thus making a classical lexis ‘sing’ in English.

Here I’ve really been referring to the kinds of lines that 10-position thinking is likely to produce. However, in order to be perceived as 10-position, our functional w stresses must all receive a degree of ‘promotion’; but ‘promotion and demotion’ are the wrong way of thinking about it. The additional projection of a 10-position cognitive template would produce a degree of convergence which would effectively insist on a subtle revision of the function of parts of speech. Ten positions of relative equality means the elongation of schwa, and the concomitant stressing of function. Making grammatical function an aspect of the sentence that now must be consciously processed will increase both its versatility and its difficulty: ‘Who is it that says most, which can say more, / Than this rich praise, that you alone are you, / In whose confine immuréd is the store / Which should example where your equal grew?’4 – and one can immediately see the appeal of 10-position to Shakespeare, the most grammatically experimental of poets.

However, s stress suffers a metronomic pull down towards the quiet zone of timed placeholding function too, so there may be a slight overall increase in 10-position line length, and the perception of the s/w/s/w/ weave being more of a gentle kink than an emphatic wave. While in theory it might all balance out, because of the social and cultural purpose to which poetry is put (and, let’s be frank, the hysterical temperament of poets generally), we tend to see instead that 10-position is exploited as means by which the event- and pitch-floor can be raised overall. A frame perceived as a monadic Gestalt is far more easily raised up as a single unit than would be an AS frame whose purpose is to preserve the strong pitch-alternation between content and function, weak and strong.

In 10-position, pitch variation between content and function words is flattened out in neutral readings; this means that the pitch-contours, emphases and de-emphases of sense stress, those which occur as a result of semantic, phrasal, syntactic or dramatic exigency, will stand more saliently against it. This makes loose i.p. ideal for dramatic performance and for personal interpretation; the attenuation of AS means that there is little pitch variation inherent in the line’s rhythm, meaning that its performed sense can be accommodated readily without perceived damage to the integrity of the line.

Finally, the partial erosion of event/placeholding roles further aids the collapse of the content-ruled axis of paradigmatic selection into the function-ruled axis of syntagmatic combination. Or to put it more simply: dramatic loose i.p. can hold more content that English sentences of the same length can usually sustain.

Lyric i.p. and the 8-strong measure

There is a significant complication to this picture. It depends upon our accepting that there are two distinct modalities, two larger cognitive templates in play, which the co-composing poet and reader may switch between (they need not coincide, but, as ever, a convergence of introjection and projection is our ideal): namely those of lyric and dramatic speech. This theory is plausible only if we can subscribe fairly wholeheartedly to my creed of non-intrinsicality: here, this means that i.p. as a 5-metron duple line generates no secondary template but its own, and is merely a neutral construct onto which other templates can be culturally projected.

Whatever its muddy origins and confused entry into the language, it would be no surprise to anyone if i.p had occasionally accommodated itself to the most pervasive metrical template of poetic speech, the 4-strong line. I feel increasingly that the 5-strong duple line is a neutral frame which has interacted with two performance traditions, the lyric and the dramatic, and has become a line capable of both ‘analogue’ and ‘digital’ interpretations; while these interpretations lie at opposite ends of the metre-strong/speech-strong performance spectrum, they might nonetheless freely interact in a way perceptible to, or at least registered by, an attuned listenership.5 Not only that, but the notorious instability of the i.p. hiatus might be partly explained by i.p.’s swithering between the two modes. (The old argument one occasionally still hears about the i.p. line ‘really only having four stresses’ – owing to some mysterious and inherent inability of the self-contained English phrase to sustain any more – is unrelated to what follows, and not worth our serious attention.) My admittedly controversial proposal is this: under lyric, end-stopped, stanzaic conditions, we sometimes see the spoken performance of i.p. tend towards an ‘analogue’, 8-metron, ‘chrysometric’, tonal, double-supratonic, generative line, one composed of five strong stresses and a hiatus roughly counted as three metrons. Sing or ‘intone’ a line of i.p. in this way, and you will soon hear it as two four-strong lines.

In dramatic blank verse, it tends towards a more ‘digital’, 10-position, isometric, syllabic, 5-strong, monadic line, composed of five duple-metre metrons and (as it is monadic) an uncountable, short hiatus of wilfully indeterminate length. (Anyone who ignores the word ‘tends’ will find this theory very easy to refute; my focus is on the performance of the line as it might be affected by the introjection and/or the projection of two different templates, which are themselves the formal aspects of two different performance modalities. It’s the existence of those English ethnolinguistic metrical frames I’m trying to show, not any ‘inherent characteristics’ of the 5-metron line, which – to repeat – is a neutral and empty construct.) The performance and perhaps composition of i.p. negotiates between these two extremes. Actors’ performances of poetic or lyric i.p. are rarely to be trusted, as they are almost invariably speech-strong, a mode only really appropriate to i.p. in blank verse, which, of course, they tend to speak supremely well. (Here is not the place to whine at length about all the great lyric poetry ruined by an actor’s desire to ‘put something of themselves into it’.) For the 4-strong effect within i.p. to be heard, one requires a measured and unexcitable performance, metre-strong and consistent with the conventions of lyric delivery, i.e. with a slower speech tempo and the downplaying of ‘interpretative emphasis’.

The argument for its existence runs as follows. To start with my conclusion: in addition to the neutral 5-metron and the dramatic 10-position templates, the i.p. line can also be an expression of two measures of 4-strong. (These metrical, dramatic and lyric modalities are i.p analogues of the metre-, speech- and song-strong interpretations of the 4-strong line, i.e. they provide a similar expressive latitude by different means.) I arrived at this while asking two questions. Firstly, why does the way we claim that we time the hiatus often differ so much from actual performance? And secondly, how would one go about setting i.p. for the singing voice? I was listening on YouTube to the Scottish actor David Tennant give what I would call a very natural, unaffected and lyric performance of Sonnet 18: he pauses longer than other actors at the interlineal hiatus. Actors are very good at blank verse, but are mostly lousy performers of the lyric mode, where they tend to rush, shortening the vowel, kinking the line with expressive accent and generally diminishing the musical experience – i.e., they read it as they would dramatic blank verse. In these circumstances, obvious, line ending-coincident syntactic breaks will receive a longer pause, but the i.p. line itself seems neither to imply nor compel any. Tennant paused at the end of each line in a way that seemed perfectly natural and, more importantly, timed and rhythmic; but for far longer that one would expect from a line which was merely making up its length to an even 6-strong stress positions by the addition of a single ghost metron. Suddenly I heard that all he would have to do would be to sing his syllables for Sonnet 18 to fit a four-bar measure almost perfectly. And indeed he basically was: Tennant was, in effect, giving a timed lyric performance of a line most would treat or read dramatically; and in doing so, fitting it almost perfectly, instinctively and effortlessly to a 4-strong template: the final stress was treated as the first stress of a new line of 4-strong, with the remaining strongs counted in silence. The availability of this alternative cognitive template suddenly made sense of much that had troubled me over these inconsistencies in our analysis.

While it is sensible to argue that the dramatic i.p. line is a kind of freelance monostich, incapable of proposing the larger stanzaic structures easily conjured from the alternate-stress-ruled 4-strong – i.p. feels bounded, odd, independent – when the line inclines to the lyric form, we find them in just such stanzaic structures all the time. Within those non-blank verse structures, we assume, I think, that we are placing something like a ghost metron to even it up, i.e.

So now I have confessed that he is thine, [x/]

And I my self am mortgaged to thy will, [x/]

Myself I’ll forfeit, so that other mine [x/]

Thou wilt restore to be my comfort still: [x/]

This argument holds reasonably well for modally neutral performances; indeed there, the hiatus need not be thought of as more than an optional – uh – between lines, one easily skipped by enjambment. And whenever the line leans more emphatically towards a dramatic delivery, the length of the hiatus varies greatly depending on the sense, and is very often cheerfully elided by enjambment produced by the dramatic necessity of the speech; compared with the 4-strong line and its ‘stanzaic consequence’, the 4 × 4 form, we think of i.p. as less lyric, and more conversational; less sung and ‘felt’, and more spoken or ‘acted’; less vowel- and weak-space elongated (it has no ‘Dolnik’ form), and more schwa-populated; less metre-strong, and more speech-strong in its prosody, with the speech tempo generally a fair bit faster. However, this only really applies to i.p. in its blank verse forms, and the loose versions of its metre. In the case of poems composed of obviously lyric, frequently end-stopped i.p. lines, such as we often encounter in more formal sonnets, the one-metron hiatus is clearly insufficient, and, I would argue, not reflected in sensitive performance; in its lyric incarnations, the single-stress hiatus can create an unnaturally rushed effect. But when I yell at a student, as I often do, to ‘read it slowly’, in a manner sympathetic to its author’s lyric intentions – another template will emerge: there’s really not that much difference, to my ear, between the effective performance of strongly lyric i.p. and 4-stress.

I think the failure to diagnose this lies in the refusal to acknowledge that there are two distinct and alternative templates, each appropriate to our two modalities, our ‘genres’ of i.p. On more than one occasion I have found myself in arguments with actors who insist that the Sonnets are a long dramatic poem, and should be read accordingly; it seems to me self-evidently the case that they are nothing of the kind. The ‘indeterminate ghost metron’ (it’s significant that this is rather oxymoronic) between lines:

So now I have confessed that he is thine – x DAH

And I my self am mortgaged to thy will – x DAH

is felt (i.e. sort-of-counted) in half time in lyric i.p. and takes up something slower to the space of three metrons, i.e. [– DAH – ] is more [ – uh – DAH – uh –]. If we insert the weak placeholders:

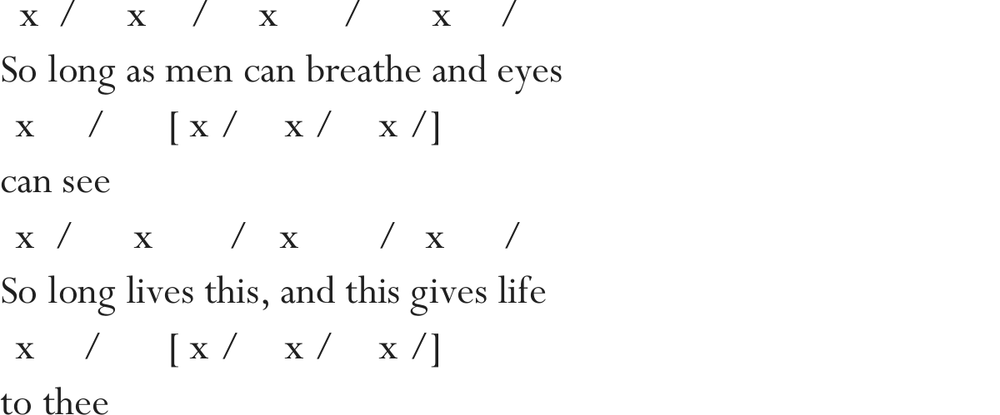

So long as men can breathe and eyes can see [x /x S x /]

Nor is this 3-metron hiatus perceived as particularly overlong, as the speech tempo of the lyric mode is far slower than the dramatic.

I believe this long interlineal gap is merely the product of a wholly instinctive mapping of i.p. to 4-strong. Consider the possibility that i.p. might be felt as a 4-stress couplet with only the first stress of the second line realised:

And lyric i.p. become as form of curtal ballad. I am aware that always counting 2, 3, 4 after every line of end-stopped lyric pentameter may feel strenuous, and I would suggest that the 3-metron hiatus is more ‘a potential space that can be comfortably expanded into’ than always realised; generally speaking, it is gestured toward by a much-longer-than-usual hiatus, and need not always be fully timed. This may be because lines often move freely between dramatic and lyric modalities, and the hiatus is therefore open to either a 1-metron or a 3-metron half-time interpretation, but is most characteristically a tensive space somewhere between both, from which either can also be realised – one we perhaps think of as especially characteristic of the i.p. line. Certainly, a 1-metron gap feels much too short in lyric i.p.; but increasingly I hear most i.p. verse gain one of its characteristic tensions as it is pushed and pulled between the modal templates of the lyric 2 × 4-strong measure and that of the dramatic, 10-position line. Whether a line is read one way or another will often be directed by content, i.e. various semantic and syntactic cues – but also by lyric properties, word choice, function-to-content ratio and so on. When an i.p. line is read in the slow, end-stopped lyric mode, the elongation of the line makes the 2 × 4 template easily available as a metrical alternative. It is not intrinsic to the form, but potentiated when i.p. lines imply a lyric performance. Much of the hiatus’s indeterminacy, therefore, rests on our being unsure if the hiatus is 1- or 3-metron, i.e. to be counted in single or half time, as we first need to be sure of a line’s dramatic or lyric modality, which affects tempo. (Another factor steering some readers towards a half-time, 3-metron hiatus may be the ternary dimetronic reading of i.p. that tends to emerge under tight-metre, endstopped conditions; here, the felt 3-strong of And SUMMer’s lease has ALL too short a DATE [xxx] can easily rebalance itself as a half-time 4-strong, i.e. And SUMMer’s lease has ALL too short a DATE [x/x S x/].) Is there any validity in claiming the existence of a template few poets or actors explicitly perform, and which could perhaps be as well explained away by the mere expressive elongation of what we all ‘just feel’ to be an indeterminate hiatus? I believe so; not least because it explains the indeterminacy of the hiatus itself without resorting to mysterious claims of intrinsic properties, and the cognitive presence of 8-strong would explain the larger symmetrical stanzaic structures into which our allegedly monadic i.p. readily forms itself under lyric circumstances.

(Again, one could easily cite the performances of the poets themselves, but as the most self-conscious performers on God’s earth, they are rarely reliable guides. Although Frost delivered the shorter, more lyric i.p. of ‘Design’ more slowly than he batters through ‘Birches’, he was a notorious rusher; to my ear ‘Design’ works far better read in something close to the lyric i.p., 2 × 4 template. On the other hand, Yeats was once asked why he paused so heavily at the end of every line; he replied, ‘So they can hear the work I’ve put in.’)

Some corollaries of the 8-strong template in i.p.

If we plug some i.p. into the numerical values of the 4-strong distrophic matrix, we see the following:

Factoring in the above will help explain a few phenomena, and propose a few interesting corollaries:

1. This is why lyric i.p. feels not just monadic but bounded: blocked out by a conspicuous silence at its end, and carrying both an initial high stress and a terminal one – and yet rhythmically balanced. What we have in lyric i.p. is a double supratonic line, derived from the high initial stress on each first stress of the 2 × 4 form. We now see the additional pressure on the final word of lyric i.p. to carry some significant semantic weight, given the greater size of the space it must resonate into – and its being thrust into a semi-symbolic role, almost through its Janus-facing position alone. (One feels one could almost reconstruct the sense of the whole poem from day? / temperate: / May, / date: / shines, / dimmed, / declines, / untrimmed: / fade, / ow’st, / shade, / grow’st, / see / thee.) Approximate rhythm between supratonic stresses is maintained by the three silence metrons performing the ‘placeholder role’ of the s stresses in the middle of the line:

So long as men can breathe and eyes can see [x/ x/ x/]

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee [x/ x/ x/]

Silent counts contract, and this 3-metron space is often performed a little shorter, though nothing like a 1-metron count.

2. This is why the last stress of lyric (not dramatic) i.p. feels unusually strong and high. I had ascribed this principally to the effect of default nuclear stress in the normal English prosodic phrase with which i.p. regularly coincides, but in this analysis, it’s part of the template: the high value of the fifth stress is merely the high position of an initial stress in 4-strong.

3. This makes i.p. potentially subservient to three templates: to a 10-position line in its dramatic form, a double supratonic line in its lyric 2 × 4 form, and a neutral 5-metron AS line which negotiates between the two.

4. This would mean that larger AS structures are in fact implied by i.p., because the single line is, in a sense, already a couplet. The i.p. couplet is then merely another expression of 4 × 4, which would explain the feeling that the heroic couplet is its natural lyric form. The common-sense assumption that i.p. has no momentum because its five strong stresses do not imply larger stanzaic structures has never been very well borne out; we feel it does, and can point to any number of examples of stanzaic, lyric i.p. where it appears to do just that, and which we can now explain.6

5. Wherever we detect an 8-strong template, we may then decide to also make some account of the ASR at the higher unit levels, including alternating key-fall patterns and larger matrical structures. I.p. can be plugged into the 4-strong AS numerical matrices, so larger forms can be analysed with none of the hesitation one would have over the 6-value (5, plus the ghost strong) line matrix earlier discussed. An i.p. quatrain would map to an eight-line distrophic 4 × 4 matrix; here, the zenith is first stress of first line, the nadir is fourth stress of fourth line, as in this short poem by Frost:

And lo, what do we find at the nadir but … The false stars of the fireflies. It’s hard to believe that Frost, in making this beautiful effect, didn’t instinctively sense that the de-accented, anaphoric repeat-word ‘stars’ and the ‘distrophic nadir’ should be coincident. (Note that in lyric i.p., while the highest value falls on the initial position, the lowest in the 4-strong distrophic matrix is always the penultimate stress of the first strophe, if the second is not complete. This is different from the position of the nadir in the strophic matrix of i.p.; the difference is in the numerical values, indicating a psychologically lower position for the nadir relative to the zenith in the 4-strong distrophic matrix – 5/32 as opposed to 5/24 – and likely reflected in a more exaggeratedly performed drop in pitch.) Though I suspect the lyric i.p. nadir can be used for more than the smooth accommodation of strong-position function, the demotion of content to function (and, as above, the burying of a repeated word to reinforce its anaphoric role), and may be deployed as a general tool of bold de-accent: in line 8 of ‘To His Sonne’, with the slyest fake insouciance, Raleigh drops in the following:

The wag, my pretty knave, betokeneth thee.

… And to my ear – by mere dint of its matrical positon – Raleigh suggests we might drop our voices down a fifth or so, Edmund Blackadder-style. (Note that the weakness of this position also makes it especially accommodating of schwa, and so polysyllabism.)

6. The numerical values leave a line with a greater overall height than two lines of 4-strong, as the lower-value final three syllables of the second 4-strong line are missing. This may psychologically confer a greater overall sense of emotional urgency on the i.p. line when read within this template. Similarly, alternating key-falls between lines will be pitched at a far higher level, leaving lyric i.p at a higher overall pitch that an equivalent passage of 4 × 4. This leaves it, naturally, a better form for ‘heightened’ language than 4 × 4 since the pitch floor itself is naturally raised by the effects of AS.

7. This has major implications for the content–function ratio, with an area of silent ‘weak function’ being delegated to the 3-metron space after each line. This leaves a speech-to-silence Fibonacci ratio of 5:8, which may have some content-to-function echoes. Speculatively (a word which should always follow ‘Fibonacci’): might the line and its long after-breath affect or effect larger structures? Might the roughly 8:5 exposition-to-development ratio of the sonnet correspond to a merely scaled-up version of 5:3 content–function line? In a sense, this would imply a scalable, ‘chrysometric’ version of AS.

8. The variable length of 3-metron hiatus is a further sophistication offered by the form. Its full value may or may not be realised, but its occasional contraction in enjambment (which occurs with considerably less frequency in its lyric forms than its dramatic) is a far more radical gesture than one would find in, say,

And down by the brimming river

I heard a lover sing

Under an arch of the railway:

‘Love has no ending.’

This leads to the increased sense of dramatic momentum wherever the hiatus is elided or shortened in lyric i.p.:

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write

Above a mortal pitch, that struck me dead?

since it not only elides a longer gap but also effectively brings two supratonic stresses (‘write/above’) together. The effect is far stronger than such an enjambment would achieve within our bundles of blank verse.

Conclusion

Poets who wish to write metrically have either a 4-strong analogue line or a 5-metron, 10-position digital line to work with, and that’s pretty much the whole show. The looser, popular 4 × 4 template tends to populate or depopulate the weak placeholder freely, and can easily shift between duple and triple metres. The upmarket i.p. line tends to overdetermine its timing more rigidly through a largely fixed syllable-count, but often takes advantage of an additional 10-position template to upgrade the weak placeholder to event-position, with predictable consequences for the syllables it then hosts. The 10-position line is a superimposition upon and not a replacement for the AS frame: its effects therefore should not be overstated. They are crucially dependent on introjection and projection, since the 10-position line would not, of course, be detected in any purely resting state prosody; it is a product of collective cultural will. This line is further complicated by folk-echoes of 4-strong itself under lyric circumstances.

Both kinds of line maintain isochrony through a degree of quantitative fixing: 4-strong through metronomic (and sometime sung, or near-sung) performance, i.p. through syllable count: one partly counts through tone, the other partly counts through syllable. The constraints inherent in both are, in practice, balanced by 4-strong’s freer w-syllable count, and i.p.’s greater expressive latitude.

1 Robert Lowell, Life Studies (London: Faber & Faber, 1959).

2 Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese and Other Poems (New York: Dover Publications, 1992).

3 An alternative explanation for this is tabled next, and I apologise for the endless drum-roll. Note that if it were the case that tight i.p. was distichic, we’d have a 12-metron form, with the first and thirteenth places occupying the first stress of each successive couplet – a thought to excite Fibonacci bores everywhere. We might then consider the eighth-placed stresses the ‘dominant’, the golden ratio tension within the couplet’s chromatic ‘scale’, and look for some unconscious positioning of significant content:

’Tis hard to say, if greater Want of Skill [x/]

Appear in Writing or in Judging ill, [x/]

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ Offence, [x/]

To tire our Patience, than mis-lead our Sense:

Some few in that, but Numbers err in this, [x/]

Ten Censure wrong for one who Writes amiss; [x/]

A Fool might once himself alone expose, [x/]

Now One in Verse makes many more in Prose. [x/]

– Alexander Pope, ‘An Essay on Criticism’

I leave the reader to decide if this is a brilliant new insight or a lunatic distraction, though I’d say the smart money is definitely on the latter.

If the reader additionally projects a strong 10-position feel into tight i.p, it will likely lead to a firm, evening ghost-metron at the hiatus, leaving a twelve-syllable count, easily felt in groups of 4; that’s to say it may potentiate the kind of a triple dimetronic count earlier discussed, with supratonic stresses on positions 2, 6 and 10. These maddening complications really just reflect a simple underlying truth: roughly fixed syllabic lines are capable of playing host to a number of projected metrical templates simultaneously, with each new template and combination of templates providing its own unique complexities. This situation will be horribly familiar to anyone who has spent any time investigating the number of harmonic systems that can be hosted by the 12-note chromatic scale – a vortex which has cost many musicians their entire lives.

4 Katherine Duncan Jones (ed.), Shakespeare’s Sonnets (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2010), Sonnet 84, 279.

5 This theory coincides with my own experience as an improvising musician. There, I hear two metrical approaches to the improvised melodic line, which I mentally characterise as ‘isometric’ and ‘chrysometric’. The first divides or multiplies the bar evenly and mathematically; most characteristically it would be something like the machine-gun ‘digital’ delivery of semiquavers over bebop changes, Charlie Parker-style. The second is ruled by the far more organic, asymmetric phrasal patterns of spoken conversational language, ruled (through a kind of projection of harmonic-series asymmetry into rhythm itself; pitch is a human projection, and just our way of hearing very fast rhythmic cycles) by golden section and Fibonacci ratios (hence ‘chryso-’, gold). Musically this might correspond to the speech-like phrasing of those musicians conventionally thought of as ‘lyric’ – Bill Evans, Miles Davis or John Abercrombie. (One common technique that jazz musicians use for learning conversational phrasing is to play along as one reads out a piece of prose fiction, following the shape and pitch-contour of the sentences in their larger narrative context.) The 4-strong interpretation of the i.p. line may be considered a kind of ‘chrysometric’, radically asymmetric ‘Fibonacci ballad’. This means the lyric i.p. line divides an ‘octaval’ 4 × 2, 8-strong template at the golden section (s stress position 5), leaving a 3-foot interstice which works in an interlineal placeholding function. (One might easily see an analogue of the V-I perfect cadence being enacted between lines – the intonational jump between stresses 4 and (nuclear stress) 5 may even perform something close to it – from which one might derive the correspondence: strong = perfect, bright, sharp; weak = plagal, dark, flat.)

6 The terminal caesura after s stress position 4 might theoretically be less disruptive in a line of lyric than 10-position dramatic i.p., since it would mark the end of a four-bar measure. The question remains as to what extent a poet writing i.p. in the lyric mode will be affected by the underlying 2 × 4 line; my sense (reviewing my own work in this context) is that I am definitely inclined to less caesural variation, but beyond that I see no pattern. However, since 4-strong is a continuous line, it implies no hiatus – and therefore no caesura here.

7 Robert Frost, The Poetry of Robert Frost: The Collected Poems, Complete and Unabridged, ed. Edward Connery Lathem (New York: Henry Holt, 2002).