Different metres require different kinds of scansion. There are four broad types of metrical composition: tight, loose, light, and free.

Tight metres disallow all but the smoothest and least radical variations, and can be described by four lexical scansion symbols:

/ – strong syllable on strong position

x – weak syllable on weak position

\ – strong syllable on weak position; potentiated demotion

X – weak syllable on strong position; potentiated promotion

The loose-metre template differs from tight metre in that it allows some freedom with syllable count in the form of w additions and omissions, and can sustain a greater number of tensions. Convergence is diminished, which is to say that the confirmation of metrical template is more difficult. I prefer to employ -x- in the top line where the weak placeholder occurs over two or more syllables, as its durational status is more evident; I save x for single-w, accurately coincident positions. (The objection here is that in using -x- you’ve gone beyond the mere projection of the frame, and have started to scan the line; to which I’d have to answer than the projection of the frame is scanning the line: the process is subjective from the start.) Otherwise the loose-metre notational system is identical to the tight, with the addition of:

x-x – double weak (either syllable of which might be subject to the usual promotions, though not both)

[x] – omitted weak

: – mora (a very short pause used as device of quantitative compensation).

These three additions are, however, syllable count and quantising marks; the basic four symbols remain the same. After a sense stress scansion, we will also encounter

/’ – accented s (the ‘high’ syllable)

/, – de-accented s

x’ – accented w

x, – de-accented w (the ‘buried’ syllable)

as well as some compound signs; in these, accent or de-accent is the more salient quality, and trumps w or s stress-qualities; it essentially ‘calls’ a tension and determines its final performed strength:

X, – promoted w with de-accent

X’ – promoted w with accent

\, – demoted s with de-accent

\’ – demoted s with accent

giving us twelve possibilities in total.

Thus, for example, [X] indicates a tension, in this case a promoted w; but [X,] indicates a tension that a sense-stress analysis has subsequently de-accented. Two kind of information are now presented. One is simply binary, and shows either agreement or tension between position and lexical stress. Tensions indicate that the w or s syllable will likely be promoted or demoted in performance – rarely to full s or w stresses, but some lighter approximation of them. However, with a sense-stress scansion, we add a more subjective, performative dimension – and sometimes an accent or de-accent will contradict a tension. This will effectively return the syllable from its potentially lowered position to its previous prominence, or vice-versa; but interestingly ‘problematised’, and deriving its complex character from both stressposition and pitch.

It would be performatively difficult to request an accent on a demoted s syllable that returned it to a position equally salient as an accent on a simple s syllable; the w position of an s syllable that is clearly accented (or, conversely, the s position of a w syllable that is de-accented) provides one of the most subtle and nuanced of available tensions: in the case of our s syllable, one which has been stress-demoted but accent-promoted. ‘Confusion’ results only when we refuse to treat it as an intrinsically unstable and tensive phenomenon. To demonstrate this complexity, let’s look at the following example:

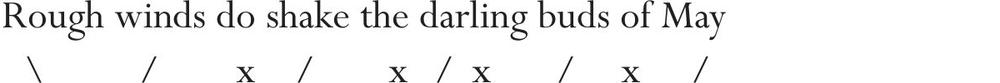

Giving:

Marking a tension at the first syllable. A tension marks a place of metrical controversy, and ‘rough’ may or may not be demoted; the voice will often perform a syllable neither exactly w nor s.

However, in the next step in our scansion, that of sense stress analysis, I feel we might have:

Here ‘rough’ is sustained against its weak position for syntactic (monosyllabic qualifier + monosyllabic noun often results in near-spondee, especially in the initial position) and emphatic sense-stress reasons (the sense demands that the subject is not ‘winds’ plus a casually descriptive qualifier, but ‘rough winds’ as a metonym for ‘bad stuff’). Note that one cannot arrive at the judgement of ‘sustained against weak position’ (i.e. a ‘refused demotion’) from a lexical scansion alone, which merely indicates tensions; it does not resolve them. Only a sense interpretation does. Nor is accent or de-accent always handily provided to resolve them either, of course. (And nor do they then necessarily resolve them; in some ways pitch accent and stress pattern can be coexistent frames, even though apparently contradictory values attach themselves to the same stress.) As I’ve mentioned, many tensions are left hanging in performance – equivocally and rather deliciously at a medial stress position, making a great variety of stress-contours – i.e. alternative interpretations – available to the line. An accent on the demoted s of ‘rough’ returns the stress to something close to its original s salience, but via a pitch, not a stress compensation.

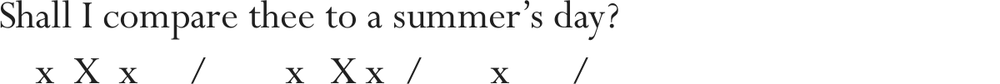

My reasons for scanning ‘the darling buds’ as [x, /, x, /,] I’ll discuss in due course. Note one miserable complication: polysyllabic words which take an accent tend to take it only on the s-syllable, and keep their weak stresses in a largely unchanged position to maintain contrast; however all syllables in the word will usually suffer the same de-accent, as pitch here is suprasegmental. The performative reality is that an entire phrase will often take the same low accent too; but for sanity and simplicity’s sake I mark only strongly phrasemic material in this way, i.e. such material in the line that is strongly lexically bound, and therefore likely to be de-accented all of a piece. (Although suprasegmental de-accent is often strongly indicated by a consecutive run of low [x]s and [x,]s and [/,]s. I had considered merely underlining the words through which the suprasegmental accent runs, but owing to the messiness of a balancing system of overlining for accent – accent most often occurring singly – I abandoned it. Phonology has its own precise systems for these things; the merit of our system is its approximate nature.) Note that my rough numerical system of intonational analysis described below preserves the same s-w difference between the two syllables of ‘darling’ as one would find in its un-de-accented state, while nonetheless marking the word’s overall intonational ‘demotion’; the information is not summed.

While I’ll describe this in more detail, the scansion procedure with tight and loose metres is roughly as follows:

1. Make a lexical scansion by projecting the template above the line, and marking the ‘resting state’ lexical prosody below it (this would include the analysis of any lexicalised phrasemic material):

2. Consolidate the information in a single notational system (after a little practice one can do this immediately, making it step 1):

3. Make a sense-stress analysis, factoring in the phonological rules of syntax and phrase, and marking such accent and de-accent as appropriate:1

4. Derive an intonational contour.

This last move is, I fear, my own ‘sophistication’; it is really a simplification, but one I believe worthwhile. Suppose that we now assume strong stresses have, as a component of their stress-quality, a normative pitch accent value of 2, and weak stresses one of 0. Our demoted s or promoted w tensions will generally lie somewhere in between, being ‘pitch-adjusted’ through the pitch-component of their stress position, so can both receive a value of one (although as merely potentiated changes they are unstable, i.e. ‘tensive’ – and will be marked as such, with an asterisk). Accent and de-accent add and subtract one respectively. This leaves us with:

/ = 2

x = 0

, = −1

’ = +1

\ = 1

X = 1

Working our way through the twelve permutations produces:

/’ = 3

/ = 2

\’ = *2

X’ = *2

x’ = 1

/, = 1

X = *1

\ = *1

\, = *0

X, = *0

x = 0

x, = −1

This gives five pitch gradations derived from our final scansion, with the unresolved tensions marked with an asterisk to indicate that the value is unstable, and that the stress can weaken or strengthen a little where the line needs to preserve ASR. (For instance a double tension [X \] will not be felt as a ‘1 1’ spondee, since AS will usually imprint itself; the tension, marked ‘*1 *1’ allows it the instability and therefore the latitude to do so.) The bell-curve distribution of the five values is important, as extremes should be rarer than median stresses. This run of numbers makes explicit two obvious phonological phenomena: where we see a large numerical difference, we will likely perform a sharp rise or fall in pitch; and where we see a run of the same or similar low or high numerical values, we will see the strong potentiation and very likely appearance of suprasegmental effect in the form of sustained and even pitch (note that this is more often neutrally even than either high or low).

Thus:

and

This forms our final scansion and accounts for both stress-value and pitch contour. Although this has little granularity, it still allows us to see the rough intonational contour of the line, and is useful as a ‘performance tablature’.

The danger of this system is that the numerical line provides only the very limited information of a rough performance note – ideally we would convert it to a single rising and falling line – and the lower line too much information, which (in, for example, resolving tensions as a single sign rather than allowing them to stand as tensions) loses the sense of a scansion as a wholly subjective interpretation. Moreover, it fails to register the suprasegmental flow of accent and de-accent, and notes them as syllabic-specific marks. (As I mentioned, I considered consolidating runs of suprasegmental accent thus:

but I’m wary of introducing further notational marks, and these don’t aid the rapid calculation of numerical values; consecutive runs of accents can be easily seen. It may nonetheless be a system worth developing in the future, as it enjoys the advantage of showing that while syllable segments, sense flows.)

At this point one might recall T. F. Brogan’s warning with a shiver, but to repeat: the alternative is a scansion that entirely ignores the sense of the poem, which might as well be a lineated plumbing manual. And where sense is concerned, as we will see, there is no alternative but discussion, flexible strategies of analysis, and a little subjective description. It’s no bad thing to be reminded that we are not dealing with a branch of the sciences; nor should we aspire to be.

I will mention, however, a hugely simplified notation I use for making rapid notes on other metrical poems, including my own, so I can recall what sense I originally made of them when I return to them later. This is especially useful if I’m required to read them in public. The dots over the vowel never occur in isolation (i.e. they indicate a suprasegmental phenomenon), and represent runs of roughly even, mid-strength consecutive stresses, usually produced by normal w promotion or s demotion (especially frequent in the 10-position loose i.p. line, where any ‘felt’ alterneity will depend on the ASR alone); the accent and de-accent marks are derived from sense stress analysis. The stress-position agreement is unmarked, which is to say the metricality of the line is taken as given (i.e. I know this is in i.p.).

(The words ‘white’ and ‘design’ are repeated, and their second appearances treated as anaphors; the other marks are, I hope, self-explanatory in the context of the poem.)

Light metre in its purest form would theoretically allow all weak placeholders to be populated with any number of w-syllables, including zero; however, this would constitute a definition of accentual verse, and in reality we must establish a ‘viable threshold’ before that point is reached (the deep problems with ‘pure’ tonal/accentual and strong-stress metres in English have been separately discussed). The closest we get to accentual verse in English are the very freest song-strong Dolnik interpretations of 4-strong; light metre cannot happily exist as a form of i.p. Some might feel that ‘Dolnik’ is really a synonym for light metre in English, but this would omit such common 4-strong-derived forms as the light ‘two-step’, a kind of slow, roughly measured, content-heavy, half-time, 2-strong line very common in contemporary poetry.

Its notation is simplified, as tensions are impossible without a clear correspondence between stress position and stress; as the number of syllables in the line becomes more and more variable, such a position-based correspondence becomes impossible to maintain in the ear, with extra or omitted syllables heard not as variations in fixed syllable count, but as part of an inbuilt latitude in the template itself. This means that we cannot derive the numbers of our intonational contour; but this is just as is should be, since the fluidity of the line also affords considerably more latitude in its sense-stress interpretation. All we require here are the following:

and (if we’re inclined):

x-x or x-x-x – double or triple weak

[x] – omitted weak

Free metre has no metrical template, and can be described by a single scansion line:

/ – s syllable

x – w syllable

/’ or x’ – s or w accent

/, or x, – s or w de-accent

However, anyone proposing a more sophisticated method of scanning free metre would have to make especial account of variations in the teleuton, free verse’s unique prosodic quality. (A start might be to attach numerical values to the line-break cline to indicate relative degrees of smoothness or disruption.)

1 The fact that these analyses are highly subjective and must be justified by articulated explanation is precisely why we should make them; they are concerned with the intelligent interpretation and performance of the line. Without them the whole process of lexical scansion can be automated, and some basic computer programs have been written to accomplish just this. (They do not, of course, conduct phrasemic analysis, which would be a sophistication only the military could fund.) The results are broadly accurate and even more broadly without any value.

2 Robert Frost, The Collected Poems (London: Vintage Classics, 2013).