Word boundaries

It is unlikely that word boundaries represent a prosodic aspect important enough to be worth bothering to account for in poetry. The first point to make is that two monosyllables have more fluidity in terms of how their stress can be interpreted than the more fixed prosody of a bisyllabic word, and this is an important consideration when establishing sense-stress latitudes; the second is that there is a good chance that the poet will have given this matter no thought whatsoever in the course of an entire lifetime. This means that such effects as are produced by the coincidence or non-coincidence of word-boundary and metrical pattern are wholly unconscious.

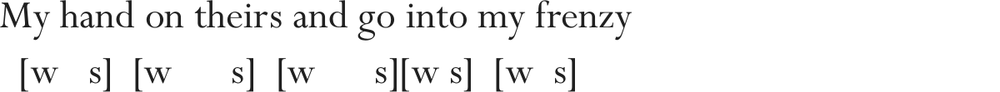

So to what extent Paul Kiparsky’s so-called ‘bracketing mismatches’,1 (when the [w-s] [w-s] [w-s] [w-s] [w-s] foot-pattern he believed to be both present and indicative of higher structures is crossed by a word) makes any difference to our perception of the line really depends on the structural integrity we are prepared to grant the iamb. I would give it very little. As I’ve mentioned, the iambic rising ‘flavour’ of lines is as much a response to normative English sentence structure, its frequent need to start with a function word (as well as the relative paucity of feminine words with which to end the phrase); there are few other justifications for the habit of cutting into the metrical wallpaper at that point. To claim that (picking two lines from Wilbur’s ‘The Mind Reader’ at random)

can meaningfully be considered as less complex or more regular than, say

– simply because in the second line the strong-onset words ‘scribble’ and ‘paramour’ run across the w-s bracketed pairings seems absurd, taking into account (a) the issue of the perception of word-boundary itself, which is often just a psychological phenomenon; (b) the prosodic complications we find at the level of local instantiation – clitic, affix, polysyllabism, phrasemic strength, nuclear stress and forty other factors; and, most compellingly, (c) the fact that there are more trochaic than iambic bisyllabic nouns and adjectives in the language anyway (verbs are more often iambic). This means the negative status of ‘mismatch’ is risked almost every time we use a bisyllabic content word that is not a verb, which at the very least points to ‘mismatch’ being the wrong word for the job, or ‘matching’ itself being a waste of time. (That said – Kiparsky’s use of the term is rigorously, if confusingly, neutral; I’m only complaining about the application of this theory to the poetic line.) ‘Boundary violation’ is not a form of perceptible ‘enjambment’, because there’s nothing to violate. Unlike the phrase and the line ending, the word does not ‘run on’ across foot boundaries, because there are no foot boundaries, and in any case word boundaries themselves are often phonologically elided.

On the contrary, it might be said that a far more pleasing effect is realised when a strong onset coincides with a strong position. Nine-month-old infants listen longer to bisyllabic words with a s-w pattern than to those with an iambic pattern,3 and generally prefer words with strong-syllable onsets. In the flow of speech, they can also detect strong-onset words far more clearly than weak-onset, whether single-syllable or polysyllabic, and – contrary to the ‘bracketing’ principle – may establish word-boundary by isolating trochaic pattern in speech. (This is consistent with the tendency in nearly all higher-level intonational phrases to go s-w, or at least high-low, and is the basis of the ASR matrix.) Whether this leads to an increased salience of strong-onset words in adult conversation is not settled, but even a vestigial effect would likely be intensified by strong-position coincidence in metred verse. My sense is that there may be not only a tendency in poetry to favour strong-onset words in strong positions in metrical verse – but strong-onset words generally. Note too that, while strong-onset words can be used in radical metrical variations on weak positions, e.g. ‘Rough winds do shake harshly the buds of May’ or ‘Rough winds batter the darling buds of May’, weak-onset bisyllabic words on strong positions are almost never used in metrical variation, and are uncomfortable, e.g. ‘Rough winds do shake the maroon buds of May’. I’m not convinced this is too mysterious: both require us to accommodate two metrical variations, one gentle and one more radical: the double w (harshly the and the maroon) is a variation of the ‘weak position rule’, while the s-syllable on the w-position (harshly the and the maroon) invokes the far bolder ‘displaced weak rule’, where we often make a mora compensation – ‘Rough winds do shake [:] harshly the buds of May’ or ‘Rough winds [:] batter the darling buds of May’. But my sense is that such double variations generally present in the order ‘more radical → less radical’, if the AS is to be re-established after the first glitch. Weak-onset bisyllables on s positions enact a ‘minor variation followed by major variation’, and feel like the template is being abandoned; the mora must be placed after the word, where its compensation only seems to make things worse: ‘Rough winds do shake the maroon [:] buds of May’. For that reason they tend to scream ‘unmetrical’.

Heavy use of strong-onset bisyllabic or polysyllabic words in s-positions probably contributes some minimal trochaic feel to the line, however, as weak onset words in w-positions will an iambic feel. But both these approaches, if applied consistently, would form a conscious or semi-conscious overdetermination of the metre; in other words, stress/word-boundary coincidence may influence where we take the start of the metron from. However, I find the difference vestigial, and for our purposes negligible. Perhaps we can try to argue that strong-onset content words in strong positions have unusually high salience, and may therefore be more theme-directive; but that would imply that weak-onset words can never enjoy such salience (a tiger will always leap out more than an impala, and a banjo sound more loudly more than a guitar). Even if there’s a grain of truth here, it remains a grain, and the argument swiftly becomes silly. (So-called ‘labelling mismatches’, the disagreement of metrical and lexical stress, are the more serious phenomenon, simply because they are audible; however, these are largely identical to the tensions described in non-generative forms of prosodic analysis.)

Stress-tree analysis

The kind of stress-tree analysis derived from generative linguistics and favoured by Kiparsky and subsequent theorists is not, I feel, particularly helpful in analysing verse prosody. Where it seems far more successful is in the analysis of the resting state prosody (RSP) of short text samples – whether in verse or not. In making these analyses, the prosodist must take care not to colour the analysis with sense stress, and indeed make sure they subscribe rigorously to the more successful of the metrical-phonological rules (such as Liberman’s rule for multiple-stress words, the normative operation of nuclear stress within spoken phrases, and so on) that govern the rhythms of well-formed speech and most written language.

However, despite its often rhythmic character, poetry provides singularly inappropriate samples for such analysis. Poetry is in some ways predicated on the immediate dismantling and subversion of its RSP, which falls to the exigencies and emergencies of metrical and emotional pressure almost immediately. It seems far more sensible to make a rough-and-ready lexical stress analysis, and then skip immediately to a sense-stress analysis. This, inevitably, provides only ‘a blueprint for performance’ – but to dismiss this as a piffling matter that can somehow be accounted for further down the analytic line is a grievous error. A poem fundamentally is a blueprint for its own performance. A scansion incorporating sense stress will give far more insight into what a poet ‘meant’, and to where they hear their pragmatic emphases and de-emphases, than any forensic description of the kind of higher-level tensions between syntax and rhythm that stress-tree analysis reveals or alleges; by the time we get to those tensions, they have already been undermined and rewritten by far more urgent linguistic, rhetorical and pragmatic concerns.

A stress-tree analysis of a difficult Shakespeare sonnet, say, would founder almost immediately on encountering Shakespeare’s habit of turning language from solid to liquid through sheer emotional heat, echolalic patterning, an almost demented thematic reflexivity, and the consequent overdetermination of thematic domain. This means he will often detach words from their native part of speech and primary denotation, and allow them to orient themselves freely according to the magnetic force-field of the poem – one he has established through a mixture of lyric signature and domain-rule metonymy. (Stress-tree your way out of ‘Even so, being full of your ne’er-cloying sweetness, / To bitter sauces did I frame my feeding, / And, sick of welfare, found a kind of meetness / To be diseased, ere that there was true needing’ or ‘Mine eye hath played the painter and hath stell’d / Thy beauty’s form in table of my heart; / My body is the frame wherein ’tis held, / And perspective it is best painter’s art’,4 if you dare.) A word in a Shakespeare verse can make its contribution as much through a kind of ‘semic ambience’ as through any paraphrasable sense; and the skills of the generative metricists are, I am afraid, largely redundant in pursuing the considerable effects this has on the prosody of the line. What a more immediately subjective scansion can tell us, however, is how tensions between rhythm and phrase both dramatise his sense and provide room for a variety of sense-interpretations, which can be pursued or confirmed through the purely descriptive process of sense-stress analysis. Poems, in their semantic instability, their deconstruction and reconstruction of phrasemic material, their blurring of function and content, their metricality and deliberate overstressing, are ‘all over the place’. A detailed tree structure hoping to unearth stress-contrast at higher phrasal levels is doomed to failure, because the connotative, unstable nature of poetic lexicality means that such structures are undermined from the bottom up.

Additionally, it is alarmingly unsympathetic to the way this poetic material has come into being. Such metrical-phrasal tensions as exist have arisen as artefacts of driving the urgent semantic and syntactic concerns of the poet against the resistance of the metrical template, not vice versa. To prioritise the metrical and prosodic in the hope that these will shed light on the semantic is the wrong way round, and places a primary emphasis on matters which, while important, are simply not as central to the art as they claim to be. Furthermore, it is also a too-easily self-justifying and circular exercise: when dealing with an unstable and polysemic text, any single reading is easily confirmed. One can easily find oneself in the position of someone standing in a garden in the middle of the night, reading a sundial with a torch, and proclaiming that they guessed the time exactly right.

No word steps into the same sense twice. (Unless it appears in a phraseme, of course, but even these are slaves to context.) Stress and sense are irrevocably connected. Stress is many things, but it is primarily a performative aspect of the properties of function and content, and these are properties which are psychologically conferred – and can therefore be switched. We’ve mentioned several times the way the second of two repeated content words in a sentence is often demoted to a weakly stressed anaphoric role: stress-tree analysis generally takes insufficient account of even this basic phonological phenomenon, never mind the more complex destabilisations of poetry. To claim that higher level w/s distinctions can be neutrally derived from lexical stress and a handful of rules ignores not only the fact that the individual signs are themselves unstable but also the fact that ‘phrasal context’ involves a higher-level, domain-ruled semanticisation – and hence a top-down supervenience on the syllabic stress of words which are themselves already problematised in their relationship to their own prosody. At the end of the day, generative metrics seems – like so much else – firmly predicated on crediting words with intrinsic value; but poetry demonstrates that this is something they possess even less than paper money or the art object. They are merely interpretable acts, and do not ‘possess’ meaning but indicate points of its contextual constraint. Poetry challenges and rewrites the generic context that confers sense on words, and can alter their local use beyond recognition.

1 Paul Kiparsky, ‘The Rhythmic Structure of English Verse’, Linguistic Inquiry 8 (1977): 189–247.

2 Richard Wilbur, The Mind Reader: New Poems (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).

3 Martin H. Kelly and Susanne Martin, ‘Domain-General Abilities Applied to Domain-Specific Tasks: Sensitivity to Probabilities in Perception, Cognition, and Language’, Lingua 92 (1994): 105–40; Peter W. Jusczyk, Anne Cutler and Nancy J. Redanz, ‘Infants’ Preference for the Predominant Stress Patterns of English Words’, Child Development 64 (1993): 675–87.

4 Sonnets 118 and 24, Shakespeare’s Sonnets, ed. Katherine Duncan Jones (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2010), 347, 159.