Against ‘inversion’

While they remain supremely insightful, I don’t quite subscribe to what Attridge calls ‘deviation rules’, or more specifically the table of the order of their complexity.1 These clines are problematic as there are too many variables, and single instantiations of so-called ‘complexity’ are mitigated or further complicated by metrical context. I prefer simply to declare the template tight, loose, light or free depending on the median level of variation, as demonstrated by whatever the reader thinks of as typical lines from a representative passage. One complication is that whatever might look fixed at the level of metrical scansion remains provisional until some contextual and syntactic account has been made of the material; this can often shift the projected template, and reverse the ‘complexity’.

Serious differences in scansion arise depending on whether we hear a poet working to a tight or loose metrical frame. Additionally, different poets also hear the rules differently; part of a ‘style’ is hearing deviations which one poet may regard as radical as relatively non-disruptive – and vice versa. For example, we know that two ws can often occupy a weak position (Attridge’s ‘double offbeat rule’ – that ‘two unstressed syllables may realise an offbeat’). This is not generally regarded as a radical or complex deviation; however, because Robert Frost only very occasionally employs it in a medial position, one can infer he treats it like one, and, to a careful reader of Frost, it also feels like one. Frost prefers his variation within an acatalectic frame, with one exception: w additions after the first stress. Confusingly, this variation is often called ‘initial inversion’, implying that the initial x/iamb has been flipped to produce a trochee, leaving two successive ws. For example, in Frost’s ‘After Apple-Picking’2 we see the following (I have notated only the deviations on the bottom line):

According to this metre-strong description, the successive ws in ‘Cherish in hand’ are produced by ‘inversion’. But compare them to the two ws which appear – in a rare deviation for Frost – in the middle of this line:

According to the scansion, two ws occupy the position of the weak placeholder; therefore one is the result of a w addition. However, you will note that, like ‘Cherish in hand …’, this line also has two ws produced by ‘initial inversion’ too:

This leaves two /xx/ patterns in the line – apparently produced by different means. The problem is that the effect on the reader is identical: all they know is that Frost has briefly held out the promise of a triple metre. (‘Magnified apples appear and then disappear’ – /xx/xx/xx/xx – would sustain it.) While one is allegedly ‘an inversion’ and the other ‘an addition’, there is no palpable difference between either variation – meaning that our metrical accountancy is simply not aligning with perceived reality. I would, therefore, not say either of the above lines had suffered an inversion at all, but call them acephalic, i.e. lines where the initial w is dropped. This is because in a speech-strong reading – of the kind, for the record, Frost explicitly demanded – there can be no inversion; and this has serious implications in terms of where we position the metrical template. The w at the end of ‘magnified’ is a simple w addition, like the extra w in ‘apples appear’, and is registered as such. (‘Magic apples appear and disappear’ is also acephalic; it does not contain the extra w in ‘magnified’, the product of the so-called ‘inversion’ – but all is still well.) The difference between ‘Cherish in hand, lift down …’ and ‘Cherish lots, lift down …’ is merely a w addition. We should allow our analysis to accord with experience, or it will be of little value:

The point is that ‘inversion’ implies a tension where none has been felt. (Unlike ‘lift down’, where the disagreement is palpable.) Frost merely has a preference for variation in the initial position, where it is most smoothly accommodated. I’d dispute that ‘inversion’ is ever an adequate description of the experience in the ear and mind of the reader. For all it looks that way in certain notated scansions – nothing is perceptibly ‘inverted’ by the ‘inverted foot’, any more than long mirror-image melodies are ever perceived as palindromic. This mistake arises through the reification of notational features (which involves unthinkingly converting temporal information to a spatial mark); it also has the fatal appeal of being more easily and less fussily notated than what’s actually happening. Wherever we encounter lexical stresses ‘out of place’ we should first see if an alternative projection will accommodate them, and not assume that the apparent disagreement has produced a tension. We do this by remembering that an -x- or x in the metre represents a duration, not a position; and then moving, expanding or contracting the metrical frame written above the line. Failure to do so will swiftly lead to some serious misdiagnoses. (The fundamental issue at the root of all this is that, while a ‘weak-stress position’ looks conveniently fluid, a weak durational placeholder is far less so, and is largely non-negotiable.)

As we’ll see, there always exists the possibility of a metre-strong performance, and this remains the quixotic preference of some readers, actors and poets. Here, the frame is projected differently, and tensions will be felt – often at the cost of natural speech. But even here, the word ‘inversion’ does not describe these tensions adequately.

The mora

For our purposes, the mora is a piece of quantitative fixing which takes the place of a weak stress in the form of a pause (nominally around the length of half a weak stress) between consecutive strong syllables. It arises in radical variations, when a w-syllable lands on a strong position but cannot be promoted. ‘Cannot’ is advised. Misunderstanding this point has led to serious errors of scansion. Let’s look at that old prosodic chestnut, Marvell’s ‘Annihilating all that’s made / To a green Thought in a green Shade.’

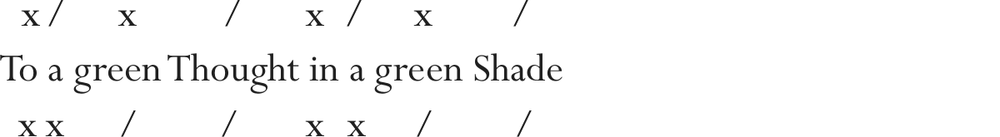

The template is a 4-strong duple line, or iambic tetrameter. The second line is often analysed thus:

i.e.

This scansion treats every metron as if it had undergone some variation. It potentiates the promotion of both ‘a’s and the demotion of both ‘green’s to something like a medial stress; it would mean that in ‘in a green Shade’ both syllables of ‘a green’ are potentiated as unstable; then, finding themselves the middle of three reasonably strong stresses (two tensive, one strong), both ‘green’s would be find themselves lightly demoted to maintain the ASR. There is, of course, no way this can ever be realised. In this strenuously metre-strong reading, the emphatic ‘ā’, which could take a stronger stress, can’t be justified by semantic context; it is clearly the poet’s intention that it remain weak, and that we should hear a radical variation. Since the dimetron xx// for x/x/ is by no means rare, this has led some theorists to rule that it represents a legitimate and metrical substitution or inversion.

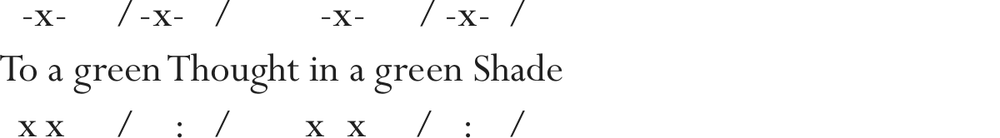

The reality is more complex. The problem lies with the projection of the template itself – and the subsequently erroneous positioning of the w placeholders above the line. ‘To a’ is not a pyrrhic substitution for the first and third feet. Almost-imperceptible but performed morae (they can be thought of as a generally silent weak uh sound, attached to the end of the first strong stress in each pair, or an elongation or diphthongisation of the first vowel) provides quantitative fixing by acting as a ghost weak, maintaining the ASR. The line is not acatalectic, but is radical because the poet has switched to a much looser metrical frame:

‘To’ is anacrustic; ‘in’ is an additional syllable; and a realised w syllable has been omitted between ‘green Thought’ and ‘green Shade’, where it has been replaced with a very brief pause. I call this addition + omission process a ‘displaced weak’, since the mora is often – but not always – accompanied by the ghost-w it replaces, which shows up in the immediate vicinity to form a double w. Both the mora and the extra w are part of the same quantitative fix; the mora fills in for the empty weak placeholder, while the extra w makes up for any lost length. There are occasions when the ‘displaced weak’ is employed and the extra w does not appear, but life is usually simpler when it does. Try losing the double ws and making the line ‘A green[:] Thought of green [:] Shade’ work as tetrameter; the mora is working overtime very uncomfortably (unless you were to actually voice it as a w ‘uh’, your instinct will be to elongate the ‘ee’ in ‘green’ into upper-class diction).

The mora is really an exercise in spondee-avoidance when the metrical pattern is / -x- / but the weak placeholder realises no syllable. The mora can take the form of a tiny gap between a consonantally closed coda and the next word’s strong onset, but can also take advantage of a variety of phonological or morphological circumstances: by ‘leaning’ on the first stress’s vowel to elongate it (‘cheap shot’ performed to a /-x-/ template will tend to ‘cheeeap [-uh] shot’); by taking any possible advantage of the potential to diphthongise the vowel (‘bare bones’ will tend to ‘bay-ahr bones’); by placing micropauses between word and affix (‘Dave’s shed’ will tend to ‘Dave-iz shed’); elongating the second stress if it is easier to do so that the first (‘big coin’ tends to ‘big coy-een’; or drawing a little more length from both stresses (‘pooor moouth’). In other words, ‘mora’ is just a cover for any old strategy where the length of the line can be increased (ideally by a discrete w-impersonating segment but often just by opportunistic stretching) to cover the missing syllable. Note that these effects are fleeting, vestigial, and perhaps more psychologically present than performed – but they are necessary to retain the integrity of the template in performance. Take the third line in this passage:

Whether or not I put my mind to it,

The world usurps me ceaselessly; my sixth

And never-resting sense is a cheap room

Black with the anger of insomnia,

(RICHARD WILBUR, ‘The Mind Reader’)4

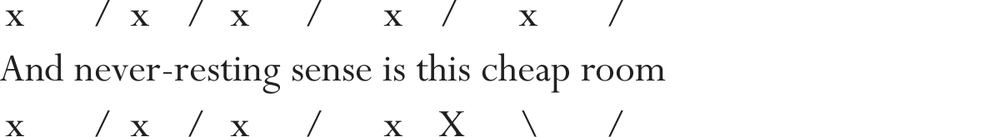

There is enough information in these lines to project a loose i.p. Just like the Marvell line, the xx// pattern of ‘is a cheap room’ is the result of a displaced weak, not an inversion or substitution, and in a speech-strong reading (I confess I have a tendency to favour them, although they are not always sympathetic to the line or the poet’s projection) is corrected by a mora:

One can hear that ‘And never-resting sense is a crappy room’ scans much the same way. (A metre-strong reading of the original line would either attempt to promote the w ‘a’ to an emphatic article, or argue for a non-existent ‘inversion’.) However, there is a significant complication.

A slightly different line with a more easily ‘promotable’ weak syllable might have encouraged the template to be projected in a crucially different, metre-strong way (as would the original line having occurred within an identifiably tight-metre context):

‘This’ is also a function word, but unlike ‘a’, it is capable of contextual promotion, meaning that it is far less likely to be heard as the radical ‘displaced weak’. This means the line will be heard as acatalectic – and that we can line up the template directly over the syllables, leaving us with potentiated promotion on ‘this’, and a demotion on ‘cheap’, and an easily preserved AS in ‘is this cheap room’, with no quantitative easing required. (The numerical contour values are 0 1* 1* 2; remember, the asterisk indicates tensive instability, meaning that although both ‘this’ and ‘cheap’ are 1s, a tensive stress can either weaken or strengthen a little wherever it needs to preserve AS.)

In conclusion: half our ‘tensions’ are really misdiagnosed. Speech-strong scansions, especially, will reveal them as really either variations produced by initial acephalsis or anacrusis, or an internal displaced weak. The moral here is that we cannot project the metre correctly until some executive decision has been made over the poem’s tighter or looser metrical frame – and that ‘best practice’ is probably to conduct lexical stress analysis and the projection of the template more or less simultaneously, so we can correct as we go.

1 ‘1. Base rules 2. Double offbeat option of second base rule 3. Promotion 4. Demotion (mid-line) 5. Demotion (initial) 6. Implied offbeat and double offbeat 7. Promotion, implied offbeat, and double offbeat 8. Demotion, double offbeat, and implied offbeat 9. Two double offbeats and two implied offbeats.’ – Derek Attridge, The Rhythms of English Poetry (New York: Routledge, 2014).

2 Robert Frost, The Collected Poems (London: Vintage Classics, 2013).

3 The lexical stress of ‘disappear’ here is emphatically /xx, to my ear – setting aside the ametrical run of three ws that xx/ (i.e. and disappear) would give us, its use here is contrastive to ‘appear’ – and when we make contrasts, the changing component (here dis-) is emphasised. In a fuller scansion, it would also receive an intonational accent.

4 Richard Wilbur, The Mind Reader: New Poems (Palo Alto, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).