What follows over the next few pages is intended to more fully illustrate the scansion procedure I have been sketching out. Given its relative complexity, I hope the reader will forgive some repetition. To be clear on the nature of the exercise: we are not attempting to work out ‘how to stress lines of poetry’. This is a false question and as such can have no answer: any intelligent reader knows exactly how to do this already. They read aloud, or to themselves, with some awareness of the underlying metre, and with some understanding of the line – and allow the agreement and tension between the two to direct their performance. What we are instead attempting here is a reasonably detailed description of the phenomenon of poetic rhythm. How detailed a prosodic description one might want to make is a matter of choice; there is no ‘threshold of common sense’ at which one should stop, beyond which one is detailing effects too small or too subjectively experienced to be verified. Who’s to say? But there is a threshold beyond which one is becoming impractically remote from the aims of the exercise. We might have chosen to simplify this procedure greatly – or expand it more deeply into the field of pragmatics and phrasal analysis. For me this method represents as much information as I can sensibly extract before the exercise becomes either self-verifying or too distant from the field of poetics.

The purpose of performing such a scansion is not, however, to describe a poem’s pattern of stress, and any scansion which stops there has lost track of its own project. The aim of a scansion is to better understand the poem, and to ally that understanding to a blueprint for its performance. Hence ‘interpretative scansion’. As an interrogative exercise, it will generate little insight if conducted speedily; and if it’s automated, it will be worse than useless.

The method I employ runs as follows:

1) We establish the metrical template. Essentially we ‘project’ the metre, based on what we can subjectively infer through a simple reading of the lines. We then notate the w-s pattern of the metre above the line, placing / and x as close to the vowel (or -x- at the mid-point of the w space) as we can. In metrical poems where liberties are taken with line length, the missing or ghost metrons can also be notated in square brackets.

We can hear that – despite its clear variations – the following passage converges quickly on an i.p. template:

2) We then write the lexical stress below the line – rigidly, taking care not to inadvertently impose stresses derived through sense stress. This is a relatively simple matter: broadly speaking, words have a well-defined and agreed RSP, which can be taken from any good dictionary. While a word like ‘the’ ‘but’ or ‘there’ might appear to take a neutral stress, in its non-emphatic use within the flow of speech it takes very little stress, and its vowel heads towards schwa; emphatic function should, by contrast, be thought of as content.3 Monosyllabic function words and grammatical affixes almost always take a weak stress, as their job is not to be consciously thought about, but to indicate a relation between contentual elements, or qualify them by inflection. After we have worked through our list of prepositions, pronouns, quantifiers, conjunctions, determiners and particles, a word’s ‘functionality’ – in metrical terms at least – becomes a slightly more complex matter. Auxiliary and modal auxiliary verbs (be/have/do, when not main verbs; can/may/will/shall/must) most often take a weak stress, but can often be easily and comfortably promoted in specific sense-contexts. (In ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ ‘shall’ is easily – and often is – promoted, albeit only by completely misconstruing the sense.) For now they should be marked weak. Disyllabic and polysyllabic function words should of course be marked according to their lexical stress pattern (‘about’ is x/, not xx).

While we’re doing this, we also mark the single-syllable content-words – nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, proper nouns – with a strong stress, or with their lexical stress pattern, if disyllabic or polysyllabic. This leaves us with a broadly accurate pattern of their RSP outside the influence of a metrical or semantic frame.

One very simple way to check the analysis is to read the lines aloud as if they were perfectly metrical, overemphasising the weak/strong alternation of the template, and make a note of which words sound strange. This will indicate where the tensions lie:

(Note: as we have seen in our discussion of the mora, there are also good arguments for making a lexical stress first, since there are many occasions when we will simply line up the template inaccurately or unsympathetically. The reality is that steps (1) and (2) ought to be conducted more or less simultaneously, so that corrections can be made on the hoof; they really constitute two parts of the single exercise of projection. The main thing to be aware of is that metre-strong and speech-strong performance styles will project the template differently, and that a degree of subjectivity is present in our scansion right from the start.)

3) We isolate any other phrasemic material that we feel to be lexically bound (I underline this material) and then adapt our lexical stress accordingly. This displays an open bias towards speech-strong interpretation (as I feel we usually should) and is a matter of judgement, since it introduces another subjective element into the process.5 However, as we’ve seen, stress operates differently in collocations than it does in content-equivalent but non-phrasemic material. In the Frost passage two lines are affected. The phrasemic ‘what do you think you’re doing’ has two s stresses if it’s a reproaching question, one if it’s a straight reprimand; here, I hear the former:

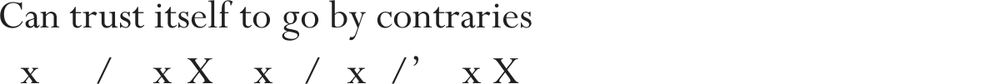

4) In the fourth line the reflexive verb ‘trust itself’ is effectively phrasemic and scanned /xx. Now we have a metrical template and lexical stress. We now consolidate the two notations to mark double weaks, omissions and tensions, i.e. the out-of-position stresses that may be promoted or demoted. (Remember stress position tensions potentiate demotion or promotion, and are unstable; they cannot insist on them.)

5) We then make a sense-stress analysis, accenting or de-accenting material according to our performance of its understood sense. This is entirely coterminous with an act of critical interpretation, and I believe a verbally articulated explanation must be made to justify such an interpretation, at the very least so other readers can disagree. To recap: while values of weakness and strength of stress are based on normative admixture of volume, pitch and length, sense stress adds a strongly intonational dimension, one difficult to represent notationally. It is what we add as performers of a line, as soon as we have semantic and emotional context. For our purposes, the primary functions of sense stress are (a) to contrastively foreground that which is new and important in terms of content; (b) to background and ‘functionalise’ information that the speaker assumes is already known, or wishes to remain low-key, or to provide the new material with contrastive salience; and (c) to add emotional information. Both (a) and (b) tend to be represented by pitch-change; (c) is communicated through a variable admixture of pitch, vowel length, loudness and timbre that it would be ludicrous to even try to represent with our (phonologically) simplified scheme, but an analysis of ‘emotional sense’, where it shades into the semantic, will often yield pitch accents too. The stress-alternation of our speech is really part of a double sign, its two parts deeply and synaesthetically wedded: weak stress indicates function; strong stress indicates content. When stresses or accents are given to function words, and when weak stresses or de-accents are given to content words, they also shift in our perception from performing syntagmatic, functional roles to having paradigmatic, information-carrying roles, and vice versa. This is especially the case with accented and de-accented syllables. A de-accented content word which the speaker wishes to background because its information is already known to the listener performs something of the cognitive function of a grammatical anaphora, whether the word is a repetition of an earlier word or not; an accented function word, on the other hand, will carry some paraphrasable lexical content (that is to say it has synonyms on the paradigmatic axis).

We might perform our sense-stress scansion thus:

‘Doing’, I think, occurs in a phrase which parodies a kind of admonition, so takes a rise; ‘other’ is contrastive; ‘country brooks’ falls as both an ‘already understood subject’ and to facilitate the salience of ‘other’ (the de-accent is, as is often the case, suprasegmental and extends over all three syllables); ‘east’ is contrastive, and forms the high nuclear stress of the question; to place an additional accent on the neutral s stress of ‘ocean’ would be to misinterpret Frost’s intentions, and diminish the contrastive effect of ‘east’. (There is a good argument for de-accenting ‘the ocean’ or even ‘to reach the ocean’ as that part of the question that is ‘common knowledge’; but while speech-strong bias is desirable, this would probably suggest its triumph. For poetry to sound like poetry, metre and speech have to be held in tension. Only actors are inclined to let speech wholly dominate.)

I hear ‘must’ as emphatic, and as often happens, contrast is preserved by de-accenting the next word, ‘be’. The intonational contour values of ‘it must be’ will be [1* 1 1], though note that these 1-values have been arrived at via three different routes. Some metre-strong readers who arrived at the same conclusions would nonetheless then allow ‘must’ to fall gently to a version of the 3-stress rule, and maintain a vestigial sense of AS. I prefer the speech-strong wrestle, and in my quick-and-dirty performance-note system mentioned earlier, such runs of equal value would be marked with dots above the vowels.

‘Contraries’ seems a straightforward nuclear stress.

6) Finally, we derive an intonational contour as a ‘performance note’; this collapses information derived from all our previous analysis. Tensive *-marked stresses are unstable. Nuclear stress will generally be indicated by the highest number, or by the final stress by default, if it occupies a highest-equal position.

Contours can be instructively compared by plugging the values into a ‘contour grid’, which I’ll discuss under loose metre scansion.

7) If we are scanning the entire poem, we may take account of ASR at the higher hierarchical levels, if they exist, indicating alternating key-fall patterns at the start of each line. We then might notate the salient zenith and nadir matrical values of the various units (e.g. the nadirs of fourth stress of the eighth line of a sonnet, or the penultimate s stress of an i.p. couplet, etc.) and then look at the values they were represented by in the intonational contour grid.6

1 For a long time I called my own approach ‘performative scansion’. I intended something a little less narrow by the word ‘performative’ than its conventional Austinian sense of ‘pertaining to an utterance that effects an action through its own performance’, but it amounts to much the same thing. There is a self-conscious and self-reflexive aspect to the poetic speech act which makes the entire enterprise an illocutionary one: it always has design, always has intent, and is always seeking to ‘enact its sense’ in some way. It achieves this through a formal overdetermination, of which its prosody is perhaps the most important aspect.

The phrase ‘performative scansion’ is originally John Hollander’s, I believe; his main issue was less with subjectively prescriptive accounts of the poem per se, but their confusion with what their authors felt were objectively descriptive ones. The New Critical rejection of such performative approaches (see Wimsatt and Beardsley, etc.) is based on a superstitious fear of subjectivity. However, as the reader will now be aware, I believe that in the absence of intrinsicality nothing can said to be ‘correct’, and that highly subjective interpretation is built deeply into the most fundamental parts of the process; pretending it isn’t merely upholds Hollander’s original complaint. But there is nothing wrong with any subjective interpretation if you give your reasons for making it; thereafter it can be judged on its common sense and wisdom.

2 Robert Frost, The Poetry of Robert Frost :The Collected Poems, Complete and Unabridged, ed. Edward Connery Lathem (New York: Henry Holt, 2002).

3 Their emphatic employment means they were ‘thought about’, and by definition are content words. In ‘Dearest, note how these two are alike: / This harpsichord pavane by Purcell / And the racer’s twelve-speed bike’ (‘Machines’, Michael Donaghy) the word ‘these’ is emphatic and receives a strong stress; it should be scanned as if it were content. (Failing to note this would likely lead the reader to project a 4-strong triple-metre template into the first line, rather than scan it – correctly – as i.p.) The more expert versifiers will often have such emphasis coincide with s stress position (as above), so the promotion – should the word still be regarded as w function – will reinforce the emphasis.

4 Richard Wilbur, The Mind Reader: New Poems (Palo Alto, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).

5 This gives us two subjective variables already – and in that part of the process many theorists would prefer to think of as more or less automated. I confess this pleases me, as prosody is no place for the algorithm. Failing to account for differences between metre-strong and speech-strong performance, and of multi-word, lexically bound material are two good reasons scanning programs are currently pretty useless.

6 My own scansion does not take in nor try to find any replacement for Attridge’s STATEMENT-EXTENSION-ANTICIPATION-ARRIVAL phrasal analysis; while attractive and elegant in its simplicity (especially when applied to free verse – an area crying out for some methodical prosodic ‘coverage’), I worry that it might be too blunt an instrument. As I’ve mentioned, I’m also unsure of its strictly metre- and poem-specific credentials, and feel that the whole area might be better tackled as part of a contemporary rhetoric.