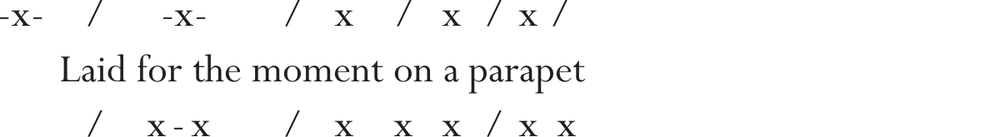

Loose metres are usually diagnosed when projecting tight metre results in too many tensions; this is usually a good sign that a loose frame has been introjected and should be sympathetically projected. Nonetheless, we always have the choice between making metre-strong and speech-strong interpretations; but loose metre actively favours and ‘asks for’ a speech-strong approach with mora compensation. Let’s look at the opening passage from Richard Wilbur’s dramatic monologue ‘The Mind Reader’,1 a poem into which we can confidently project a loose i.p., and apply broadly the same method we did to Sonnet 18, with minor variations. (It is simpler than some examples I might have chosen, as Wilbur has little fondness for the use or subversion of the phraseme; note, also, this poem is clearly written in the dramatic mode of i.p., and is resolutely 10-position, with little hint of 8-strong anywhere in its template.) Each line emerges with a largely unique contour. First, a metrical scansion:

Devilment, I admit. Many would, I suspect, place x / over ‘Think of’, and call it a tension. I take a speech-strong approach, and read it as a displaced w with the mora on the caesura.

The acephalsis is helped by the feminine ending of the previous line. Loose metre templates, as we’ve seen, will often project acephalsis where tight would produce a tension on the weak first position.

‘If you like’ is a phraseme of the ‘empty phatic filler’ variety, and to my ear can take three weak stresses. This would overrule the strong ‘like’, creating a tension, and in turn propose the xx/:/ variant of the displaced w rule in ‘you like, plunge down’:

– though this would represent more speech-strong bias than I can reasonably summon. Most readers will position the template as I first notated it: acephalic, but otherwise coinciding with the syllables.

‘Lob up’ is a phrasal verb, albeit an unusual one; ‘up’ aligns well enough with the first s position, so I don’t hear the line as acephalic.

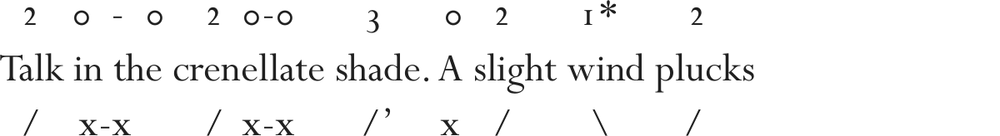

‘You can imagine’ is roughly phrasemic, reducing ‘can’ to a w. The next line is unstable:

‘Down’ I hear strong, as part of the interrupted phrasal verb ‘fall down’. (Although if we read ‘that’ as firmly contrastive to ‘another’, it’s emphatic, and therefore rises to s-stressed content; the line might then be scanned as acatalectic:

– though this would provide three successive tensions on ‘down through that’. These are generally unmetrical but are very occasionally justified through a variant of the ‘initial rule’.)

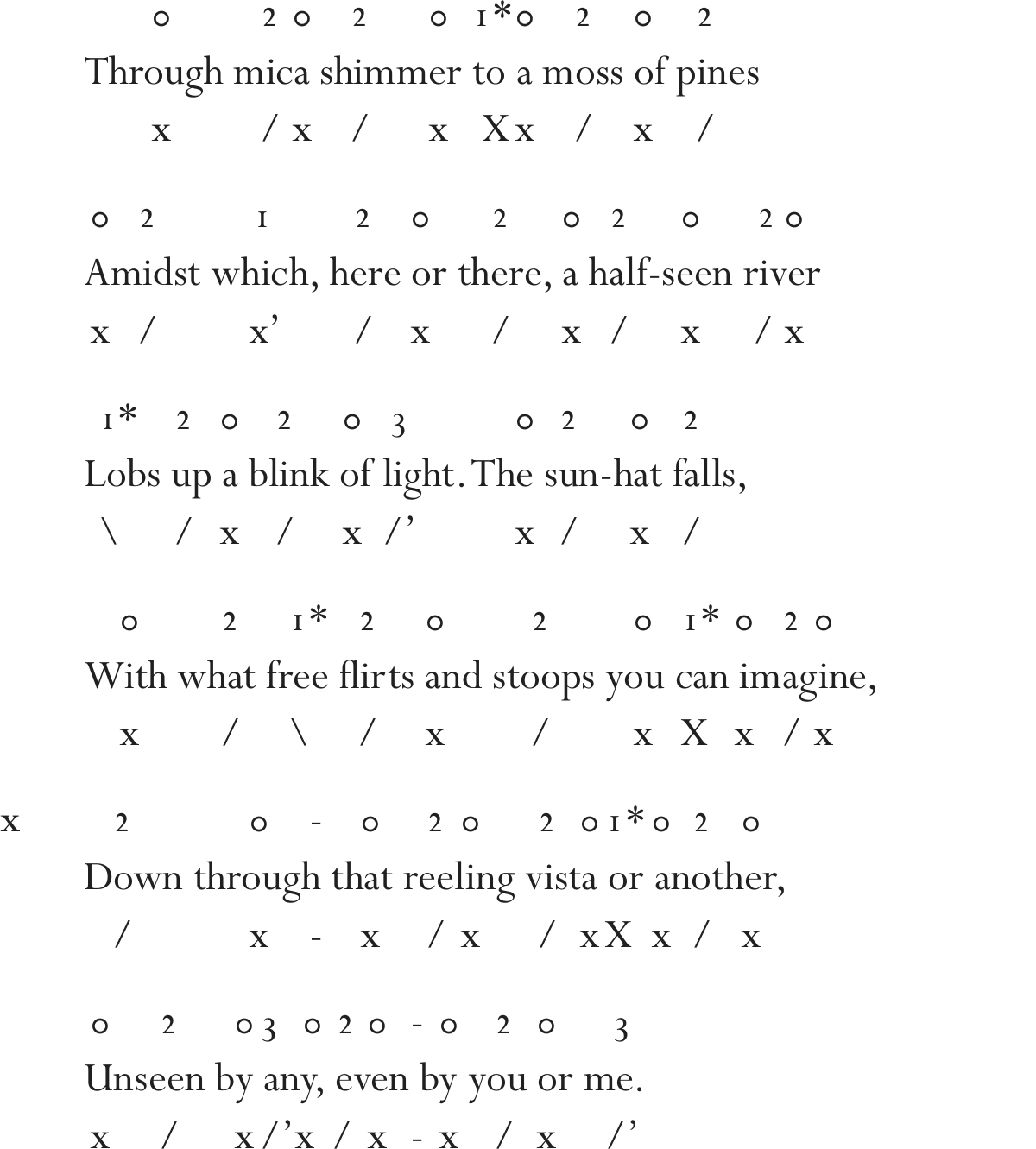

Then we consolidate the information:

Then we make a sense-stress analysis:

The sense is ‘some things are truly lost’ (as opposed to most lost things, which we hear the speaker describe elsewhere as broadly findable). ‘Lost’ should take an anaphoric de-accent as ‘the understood subject’. This is a fine rhetorical trick: the subject has not even been introduced yet, but the poem concerns itself with the nature of ‘lostness’, and the de-accent gives us the impression – absolutely correctly – of someone starting in medias res. (‘Things’ might too, but I prefer the even stresses on the first two syllables.) ‘Think’ is a bold imperative, and more important than ‘sun-hat’, the first of only a number of exempla; therefore ‘think’ receives an accent as the NS.

This is straightforward – it’s a long aside, really, and so the pitch range is tonally constrained.

Again, a flatly delivered line.

Ditto, with a nuclear stress on ‘shade’, which we can accent to communicate a sense of intrigue. (Note how the brief dip into triple metre enhances the ‘talkiness’ of the line.)

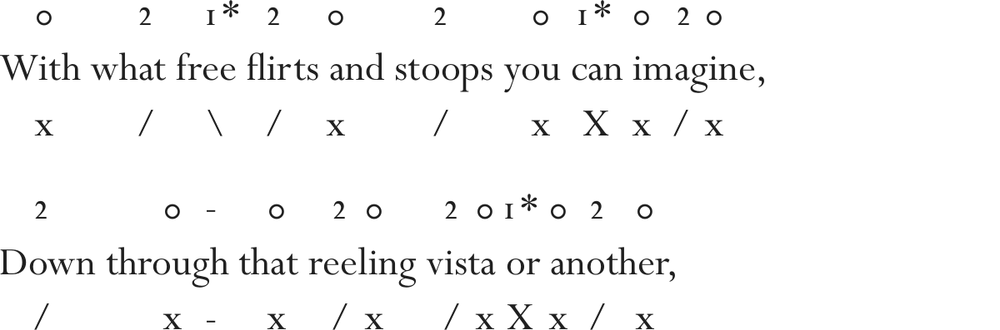

I’d keep this monotone, although words like ‘giant view’ might cue us up for a bit of drama; however ‘of some description’ reveal the speaker as also dismissively throwing the example away as almost tiresome, hence my de-accenting the phrase.

I hear an ‘oh all right then, if you insist’ here, with a rise on ‘escarpments’.

Here, the tensive ‘to’ should do a little to maintain AS, but otherwise remains below the radar.

The emphatic and rhetorical use of ‘which’ will probably see it accented despite it being an anaphor. (Note the unusual lack of variation here: to see a run of neat 0s and 2s in the contour grid would indicate a very weak poem indeed.)

A forceful NS on ‘light’, I think.

Letting the metre do the work in these last two lines …

A strong NS accent on ‘any’, after an intonationally flat couple of lines, and a sly rise on ‘me’ as the speaker introduces the subject of both himself and his peculiar expertise.

Marking the acephalic lines, this leaves us with:

In a long poem like this without closed couplets or regular, even stanzas which show some clear stanzaic definition in their syntax, the ASR cannot operate at higher unit levels than the line, though it may be perceptible within clearly defined, longer sentence- and paragraph-units.

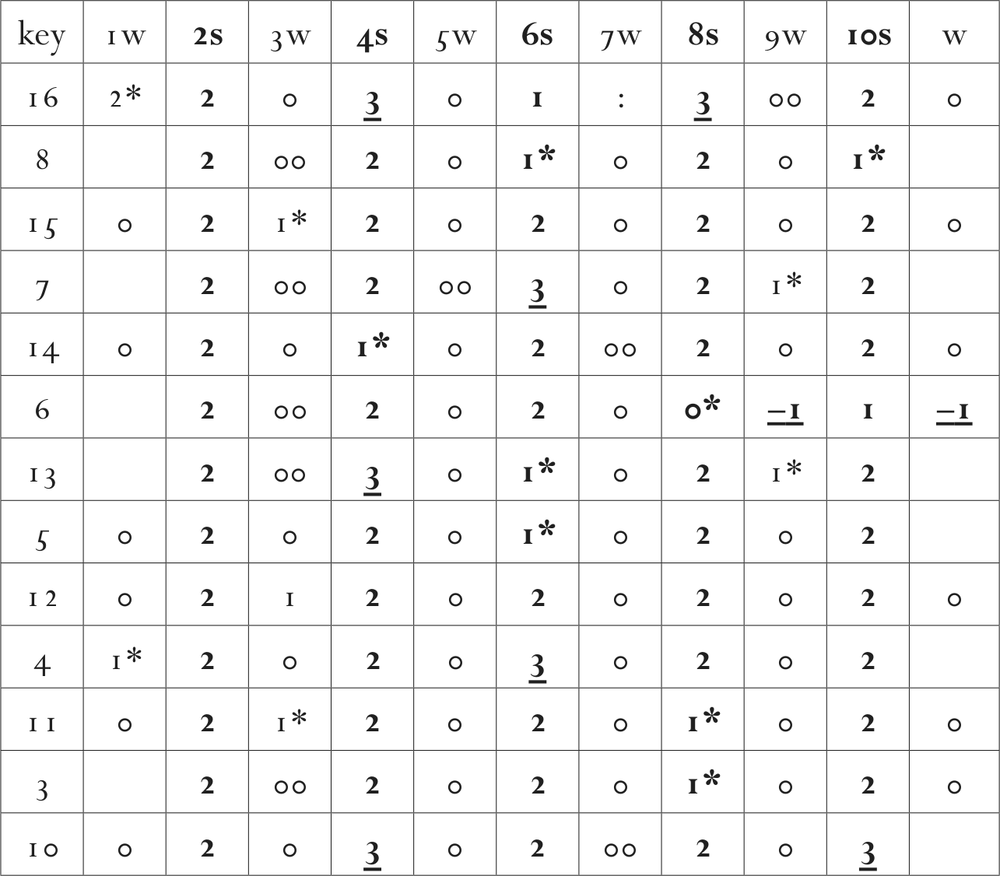

The contour grid

Plugging all values into a 10-position row allows us as before to compare echoed contours, detect overregularity, analyse the frequency of variation according to position, and so on. It can hardly be considered a ‘statistical’ tool, given the subjectivity of sense-stress analysis and its effect of ‘nailing’ even unstable tensions to a value – but it will illustrate statistical and stylistic tendencies. Wilbur’s lines display lots of variety in the sixth and eighth s positions. The high nuclear stress of the 3s is very (and pleasingly) varied; it should be no surprise to find no 3s in the first position, where the NS would be least expected. Only the fourth and tenth w positions show any demoted syllables; the second s position is rigidly consistent and the other positions are remarkably regular. Weak placeholder variation is far more radical in the third and ninth positions than the medial positions. It also demonstrates the frequency of feminine endings + s stress line-beginnings, especially where the line is enjambed; the fact that feminine endings smoothly mitigate acephalic lines reinforces my claim that /xx/ arrangements in the initial position are not the result of ‘first foot inversion’ but merely a variation of the ‘displaced weak rule’, where the initial w has been omitted, and the slack taken up by the extra w-syllable – which also serves to re-establish immediately the rising iambic feel of the metre. The grid overleaf has a column for key-fall alternation, and if the lines had been stanzaic this would have been simple to fill in. Nonetheless, the passage forms a very tightly structured paragraph-unit, and to my ear AS key-fall is fairly easily projected once the passage is known. The first accommodating binary unit is distrophic, so I’ve marked in these values here.

1 Richard Wilbur, The Mind Reader: New Poems (Palo Alto, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).