To give a rather extreme example of the sort of confusion that can arise when dealing with light metres: one theorist claims that the first two lines of Auden’s ‘Epitaph on a Tyrant’ are ‘in’ tetrameter:

Perfection, of a kind, was what he was after,

And the poetry he invented was easy to understand;1

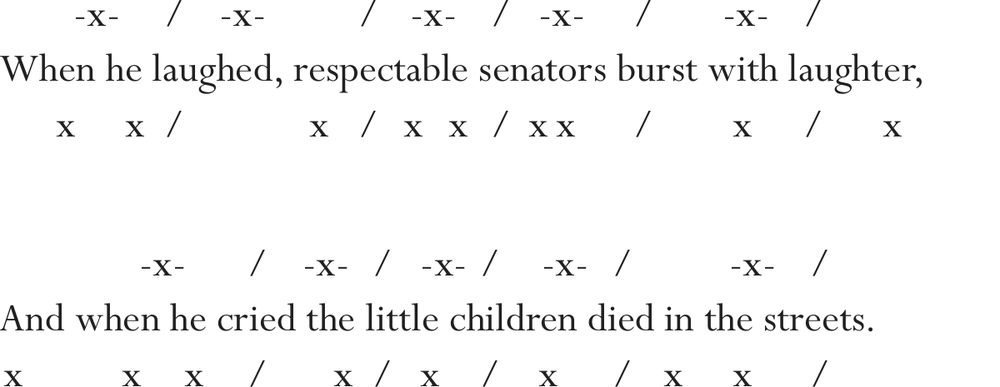

I’m pretty certain they’re not. But the point is … nor am I certain they are in pentameter, or indeed anything else. However, my reasons for thinking that the poet may have had a pentametrical frame in mind lie in the last lines, when a metrical template is most plausibly established through two convergent lines (remember light metre scansions should only have -x- placeholders marked):

My ‘i.p. suspicions’ are aroused as much by an underlying light-metre 3-strong scansion as a 5-strong scansion:

This retrospectively confirms my suspicion that lines 1–2 may also be written to (the prepositional distinction is crucial here) a 3-stress dimetronic or pentametrical frame. (I suspect ‘3-stress dimetronic’ may occasionally be the light-metre equivalent, if one exists, of i.p. I.p. is for most poets a 10-position template, meaning that it rarely if ever moves from loose to light, and if it does may no longer be i.p. in any sense; unlike 4-strong, i.p. is almost never introjected unconsciously – but with Auden, all bets are off.)

‘What he was after’ is borderline phrasemic, and tends to scan x x x / x; ‘easy to understand’ is semi-phrasemic, I feel – and can take a w on ‘easy’ and save its big stress for ‘-stand’. (‘Understand’ can scan as anapaest or amphimacer, but I feel the phraseme should always win, if it’s not being regrammaticised through innovative re-presentation.) However, if we engage our projective capabilities, it hardly takes a great effort of will to turn the lines into tetrameter either:

Though there seems to me no compelling reason for doing so, especially on a second pass, when the bolder 3/5-stress of the last lines are now there for retrospective projecting.

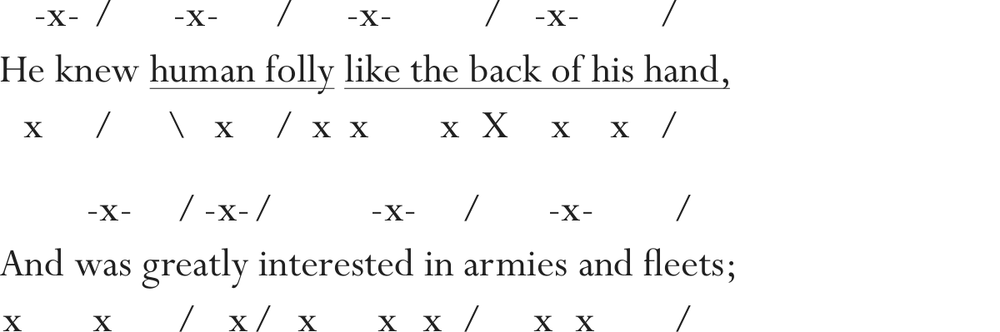

If we try to read the middle lines as tetrameter:

‘human folly’ is a very borderline phrasemic collocation, and spoken as x x/x, so ‘human’ is an easy demotion. The weaks are just regular enough to imply a strong triple metre, which helps the demotion too. However, ‘like the back of his hand’ is definitely phrasemic, and often spoken x x x x x /; I would quite like to mark ‘back’ as an X, a promoted w but in light metre this seems a bit of a cheek really. The line ‘And was greatly interested in armies and fleets’ can be scanned as a loose tetrameter with reasonable ease, but this is perhaps the only line.

So if we can buy the notion that dimetronic 3-strong is a light-metre version of pentameter, one can again hear i.p. as Auden’s introjected frame. At least, that’s the way I prefer to hear it:

But line four doesn’t fit, and this scansion is monumentally subjective. While such poems present interesting problems, they are not ultimately capable of proposing anything like a broadly agreed scansion – and should therefore be designated as metrically unstable, which is a perfectly admissible diagnosis. Light metre is often at the edge of free metre, and it’s a waste of time our trying to project any template at all. In any sympathetic reading, the act of projection must be commensurate to the act of introjection, and if it greatly exceeds it – as I think does the above exercise – we move rather seamlessly from a metrical definition of projection to a neurotic one. The simple point should be made that, if it’s this hard to project a template, the chances are that a template has not been introjected to any significant degree; Auden simply wasn’t overthinking this one.

Far easier are those light metres which tend towards loose. I’ll make a full scansion of a few lines of Paul Muldoon’s ‘Immram’, in which I think a 4-strong line can be strongly projected, even though I suspect its introjection by the poet was an intuitive (though not unconscious) affair. While the sense stress scansion is as subjective as ever, I hear only the last line in this passage as metrically unstable, a significant part of its closural effect (especially the exquisite metapoetic strain on ‘new strain’). Note that weak placeholders can be populated with not only multiple syllables in light metre, but also both ws and demoted s stresses. ‘Out of the blue’ and arguably ‘little weight’ are phrasemic. I have interpreted the second ‘ass-hole’ as anaphoric, and it should therefore be de-accented (a sentence I feel I have waited my whole life to type). I’ll leave the reader to work out why I accented the other lines in the way that I did, and then – as they should, as a point of principle – disagree. Light verse may be scanned, provided one never tries to win any consensus and one realises that as soon as tension has been identified one has really switched to the projection of a loose template. Its definition lies in its permitting many interpretative possibilities.

From the contour grid we can see that weak space is heavily (and sometimes adventurously) populated, tensions are concentrated midline, and there is a higher-than-usual degree of high accent: