I feel safe in the rhythm and flow of ever-changing life.

Madeline was a twenty-six-year-old woman who had experienced abnormal menstrual cycles throughout her entire life. Her menstrual cycles would make an appearance once or twice per year, and when they did, they were exceptionally heavy and painful. Madeline oft en had to call in sick to work for the first days of her period, spending the day in agony with a heating pad pressed up against her belly. Madeline was diagnosed with PCOS early on as a teenager and was placed on birth control pills rather promptly. At the age of twenty-five, she had read about the risks associated with hormonal birth control and decided to come off of the pill for good.

Unfortunately, this did not turn out so well. Her periods didn’t return with a normal, regular cycle, as she had so optimistically hoped. Just as they were before, her cycles arrived few and far between, and there were no signs of ovulation on her test kits. Madeline came to see me at the clinic to get some help and to effectively regulate her hormones. We started with some testing to look at the function of her pituitary gland and how it was communicating with her ovaries, and therein lay the issue. We began a course of herbal medicine along with natural progesterone cream. Just as we had hoped, her cycles returned in two months. With more work on nutrition and addressing stress, over eight more months, Madeline was able to achieve regular twenty-nine-day ovulatory cycles without the help of any medication for the very first time in her life.

As women, we are synonymous with change. Our fundamental nature shifts throughout our lives, and our hormones change their complex patterns in a similar style. This is the result of a variety of feedback mechanisms, ebbing and flowing, creating what we experience as our monthly cycles.

There are three main areas in the body to know about when it comes to understanding our female hormones. The first two of these are located in our brains. The hypothalamus is the hormone control center of the brain. It’s located deep within our brains, and one of its most important functions is to link our nervous system to our hormonal system. The hypothalamus communicates with a small gland that is directly in front of it, the pituitary. You’ve probably heard of the pituitary gland already, as it’s really the master gland, controlling the various hormonal systems in the body.

The hypothalamus, being a very sensitive area of the brain, picks up on a lot that is going on around us and directs the pituitary to adjust the hormonal environment in the body. The pituitary then, under direction of the hypothalamus, sends out messages to the ovaries, the thyroid, the adrenal glands, and more.

Since this book is about PCOS, we will be placing a lot of emphasis on the ovary. The ovary is our main estrogen- and progesterone-producing gland, and it is responsible for overall female hormonal balance and the process of ovulation itself.

The ovary picks up on the signals from the pituitary gland and responds by growing follicles for each ovarian cycle. These follicles, which house the eggs, are responsible for producing the vast majority of female hormones found in the body. The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries are three key areas that work in concert, talking to each other though complex feedback loops and adjusting as needed.

One of the most important things to understand is that when we ovulate, our eggs do not just pop up out of nowhere. They grow very slowly for around three hundred and sixty days from tiny primordial follicles before they are developed enough for ovulation. When we are newborn babies, we already have the tiny follicles containing the eggs that we will ovulate throughout our lives.

The follicles reside in dormancy for many years, waiting patiently for their turn to be ovulated. As we reach puberty, some of these eggs, housed snugly within their follicles, will begin their preparation for ovulation. During this yearlong process, known as folliculogenesis, the cells of the follicles that surround the egg will grow and multiply.

As the follicle develops, its many cells multiply and begin producing hormones. There are two parts to the follicle’s structure: the inner part, known as the granulosa, and the outer part, known as the theca. The egg is sheltered deep within the follicle, at the center of the granulosa cells.

As the follicle develops in preparation for ovulation, the granulosa produces estrogen, and the theca produces testosterone. Several eggs develop together for a given cycle, the best one of the batch is selected for ovulation, and the rest will undergo a process of disintegration. In fact, the vast majority of all follicles that undergo folliculogenesis will not make the journey. As the chosen follicle for any given cycle approaches ovulation, it produces increasing amounts of hormones, namely estrogen, along with some testosterone.

The pituitary gland plays an important role in this process. When it senses that there is a low level of estrogen, as is the case when the menstrual period begins each cycle, it responds by sending hormonal signals to the ovary to prepare an egg for ovulation. The hormone used to prepare the follicles for ovulation is known as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

The pituitary uses FSH to stimulate the ovary and then selects the strongest, best follicle to survive. The other follicles will disintegrate. As the selected follicle gets bigger, its granulosa cells produce estrogen. This peak of estrogen is a signal to the pituitary gland that a follicle is mature and ready for ovulation.

The pituitary gland responds to the high level of estrogen by sending out a pulse of luteinizing hormone (LH). This pulse of LH is what ovulation test kits pick up. LH is produced in a short, powerful surge, triggering the egg’s final development and release by causing the follicle to rupture.

After ovulation, the now-empty follicle’s work is not yet done. The follicle undergoes a massive transformation, turning into an important structure called the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum has a crucial role to play, as it is the key producer of progesterone in women. The corpus luteum is needed for hormone balance and for implantation of the embryo, should an egg be fertilized.

The corpus luteum should last around fourteen days before it disintegrates. During its lifespan, it performs the important task of releasing progesterone along with some estrogen. The corpus luteum is an independent preprogrammed structure. It requires a huge amount of blood flow and energy to keep itself alive. The corpus luteum doesn’t get any feedback from the pituitary like the ovary does, and when it has reached its lifespan of two weeks, it simply breaks down.

Knowing that the corpus luteum is formed out of the cells of the follicle, its ability to produce sufficient progesterone is totally dependent on the quality of the follicle that has developed for many months before. The cells of the follicle that become the corpus luteum must be structured well enough to survive and produce hormones through to the very end of the luteal phase.

At the end of this fourteen-day period, the corpus luteum breaks down and progesterone and estrogen levels drop, causing the shedding of the endometrial lining through the menstrual period. The pituitary gland senses low levels of estrogen and responds by releasing FSH again, preparing the ovary to develop another group of follicles for the next cycle.

As you can see, there is a lot of back and forth communication between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the ovaries in a woman’s menstrual cycle. For women with PCOS, we know that this communication is quite disrupted.

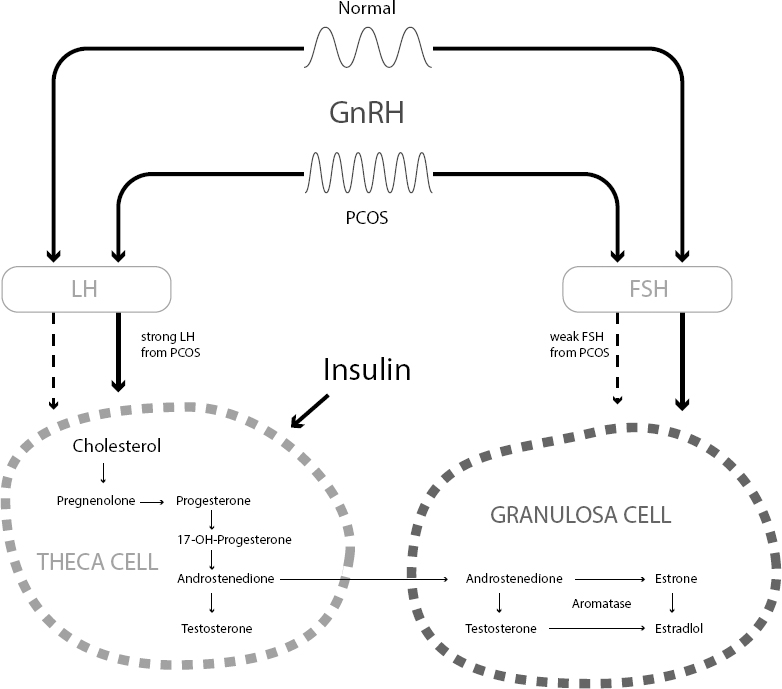

In women who do not ovulate, there is a hormonal flatline. When it comes to the hypothalamus in PCOS, it is thought that there are primary changes in the way it sends signals to the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus tells the pituitary gland what to do by sending out pulses of a hormone called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). When it pulses slowly, it triggers the release of FSH. When it pulses more quickly, it triggers the release of LH. As mentioned previously, teenage girls tend to have faster pulses of GnRH, causing a predominance of LH, but this gradually shifts to its typical female pattern of slow pulsing at the beginning of each cycle. The elevated progesterone and estrogen levels in the luteal phase typically slow down the pulses of GnRH in preparation for the next cycle. This is not so in PCOS.

In women with PCOS, the GnRH pulses do not slow down enough in response to estrogen and progesterone levels, and as a result, GnRH continues pulsing too fast. The predominance of fast pulsing results in overproduction of LH across the cycle. LH causes the ovary to make more testosterone, which inhibits ovulation (as shown in Figure 6-1).

Figure 6-1: Hypothalamus Pituitary Ovary

In PCOS, the follicles have an unusual structure: The outer theca layer is too thick when compared to the inner granulosa layer. This is caused by too much insulin and LH—common problems in PCOS.

As mentioned before, the theca cells are responsible for producing testosterone, and the follicles begin to oversecrete testosterone relative to estrogen. Too much testosterone within the ovary slows down follicular development. There is no mid-cycle surge of estrogen as the follicles grow, and there is no responding surge of LH to trigger ovulation.

As you can see, this is a vicious cycle that flattens our natural hormonal rhythms. The all-important hormonal feedback loops that keep ovulation going are completely lost.

Over time, follicles may partially develop in a PCOS ovary as they attempt to grow. As this happens, estrogen begins to rise, but testosterone overrides it, and the follicle comes to a premature halt. Estrogen doesn’t get the opportunity to rise high enough to stimulate a surge in LH and a successful ovulation.

Even if ovulation is achieved, the quality of the follicle in PCOS is usually decreased. The corpus luteum, the progesterone-producing structure of the follicle, is often not as robust and may disintegrate early. As a result, even when they do ovulate, many women with PCOS have a serious deficiency of progesterone.

Another more recently discovered hormone, known as anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), also comes into play. Women with PCOS have too many of what are known as antral follicles. These antral follicles include the stalled follicles just described, and they secrete plenty of AMH.

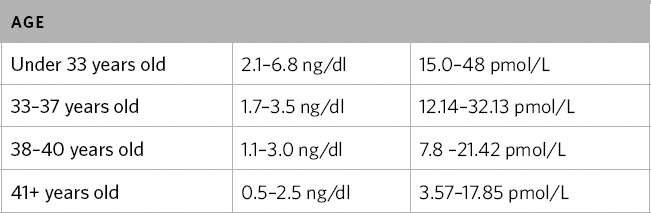

This hormone is often tested in fertility clinics to assess the number of eggs in a woman’s ovary. As would be expected, the number is often highest in young women and lower as women get older. However, for women with PCOS, AMH levels are often elevated due to both the increased number of follicles in the ovary and the fact that the follicles themselves produce increased amounts of AMH in PCOS.1 As such, AMH is a useful test for ovarian hormone imbalance for women with PCOS. Table 6-1 shows the normal ranges of AMH. If you are above this range for your age, this is a marker of PCOS. An overabundance of AMH slows down follicle development, further perpetuating the cycle of hormonal imbalance and anovulation.

New information also suggests that AMH plays an important role in the brain as well as in the ovary. High levels of AMH can excite neurons in the hypothalamus, causing them to release GnRH at a higher frequency.2 This causes the pituitary to make more LH, adding back into the cycle of androgen production in PCOS.

Table 6-1: Typical Age-Related Ranges for AMH

These are compiled from evidence and our own clinical experience at the clinic working with fertility patients and women with PCOS. (McCulloch 2015; Yoo et al. 2011; Gleicher 2016)

Women with PCOS often benefit from the following tests to assess hormones and ovarian function. If you have menstrual cycles and are ovulatory, you should have the tests completed on the days indicated. If you do not, these can also be done on any random day. Day 1 of a menstrual cycle is the first morning you wake up with a full flow of menstrual bleeding (not including spotting).

Table 6-2: Tests to Assess Hormones and Ovarian Function

HORMONE |

NOTES |

FSH, LH |

Should be done on Day 3 of your cycle. Reference: In most cases, FSH is higher than LH on Cycle Day 3, although sometimes the two numbers can be equal. In women with PCOS, the LH is often higher than FSH and can be double or even triple the FSH level. |

Estradiol |

Should be completed on Day 3 of your cycle. Reference: 25-75 pg/ml or 91-275 pmol/L |

Progesterone |

If possible, seven days after ovulation is the ideal time to test progesterone. Reference |

Prolactin |

This can be tested on any cycle day. This is a pituitary hormone that inhibits ovulation and can be increased in PCOS. |

AMH |

This can be tested on any cycle day. Please refer to previous table for reference ranges. |

(Mayo Medical Laboratories 2016; Woo et al. 2015; Buyalos, Daneshmand, and Brzechffa 1997)

Once again, the most commonly prescribed conventional therapy for women with PCOS is the oral contraceptive pill. This involves the use of synthetic hormones, which completely override the entire hormonal system. Using birth control pills will, in fact, lead to a period every month, but they will not help you to ovulate. The synthetic forms of progesterone found in the birth control pill are particularly risky. They’ve been linked to blood clots and strokes. As mentioned in chapter 5, the birth control pills most commonly used for PCOS are the ones that have the highest risks, and women with PCOS are already at increased risk for blood clots.

One issue that is common in women with PCOS is something called post-pill amenorrhea, which is the lapse of the menstrual cycle and ovulation for quite some time after women have stopped taking birth control pills. The reason that I believe women with PCOS are more prone to this is that the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary connection doesn’t have the same ability to kick back into its feedback loops after a hormonal change. I’ve seen women with PCOS take upward of eighteen months for their periods to return after stopping the pill. That being said, not all women experience this. It just seems to be more common in PCOS when compared to the general population.

Another commonly used intervention is the administration of a dose of progesterone, often for seven days, to induce a menstrual bleed. This, once again, does not induce ovulation. However, this is something I do not consider as harmful, particularly if a woman has not had a period in months. It is likely necessary to induce shedding of the lining after three to four months without menstruation (particularly if a woman commonly has very long intervals between her periods) to prevent a condition called endometrial hyperplasia.3 Endometrial hyperplasia is an overgrowth of the endometrial lining due to a deficiency of progesterone and prolonged exposure to estrogen. Over time, this can increase risk for endometrial cancer. There are natural forms of progesterone, such as bio-identical progesterone creams, that can also be used to induce a period.

The rebalancing of the hormonal axis in PCOS is something that depends on many factors. This is why I address it after what I consider to be blockages, such as insulin resistance, stress, androgen excess, and inflammation. That being said, there are some effective natural therapies that can help to reset the hormonal axis. My favorite approach when it comes to natural therapies is to use herbal medicines. These gently stimulate changes in hormones, which can provide feedback to the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovary. These treatments should not be used long term, but rather for a treatment course to reinstate hormonal feedback loops.

In women who do not have regular menses, I will often create a cycle for them, numbering days as we go. In women with PCOS who do have a cycle, we always count Day 1 as the first day a woman wakes up with a full menstrual bleed. The following are some of my favorite herbal combinations for women with PCOS.

White peony root and licorice can help reinstate cycles for women with PCOS—particularly for those where androgen excess is overriding the ovulatory process. This formula, which is comprised of a one to one ratio of each plant, can be used all cycle long and can improve ovulation rates. A study on thirty-four Japanese women with PCOS found that 7.5 grams of this formula per day was able to improve the FSH to LH ratio, reduce testosterone levels, and improve the ratio of estradiol to testosterone.4

Black cohosh is helpful in many ways for women with PCOS. It has been found to improve the FSH to LH ratio, increase progesterone levels, and induce ovulation. It may be used during either phase of the cycle. However, it should not be used by anyone with liver disease, and liver enzymes should be monitored to ensure that you can tolerate this herb.

Black cohosh has also been found to modulate the pituitary, reducing the secretion of LH.5 For women who are taking clomiphene, the most common first-line fertility drug, research has found that black cohosh can improve the negative effects of the drug on endometrial lining and cervical mucus and improve luteal phase progesterone and pregnancy rates.6, 7

Vitex, or chaste tree, is exceptionally effective for women who have elevated prolactin.8 It is clear that it reduces prolactin through effects on the dopaminergic system of the brain.

In initial studies and older herbal textbooks, vitex was reported to increase LH, stimulating ovulation and progesterone production. Of course, this created great confusion as to how this herb actually worked, when clinically it does seem to benefit many women with PCOS who have inherently high LH levels. It has, in traditional herbal medicine, been used a cycle regulator, so something within its action on the hormonal system wasn’t quite fully explained by this older research.

Fascinating newer research has determined that much of the way vitex works lies within its action on the brain. Its ability to regulate the cycle involves its action on the brain’s dopaminergic and opioid systems. Effects on the pituitary hormones are secondary. With respect to LH, clearly of concern for women with PCOS, further studies have found differing results than preliminary findings indicated. As an example, in a recent study on male mice, vitex was found to reduce the levels of LH.9 In yet another study on female mice, it was found to have no effect on LH in reproductive-age animals, yet was able to lower the hormone in menopausal rats.10 Confused yet? Don’t be. I’m going to explain how vitex can and does affect the pituitary hormones but does so at a higher regulatory level within the brain.

The main thing to understand with vitex is that it clearly does not increase or decrease specific hormones in the same way that taking a hormonal drug would, or this would be very evident from the numerous recent studies on this plant.

What it does appear to do is to act on the brain, regulating hormones from a higher level. Clinically, in certain situations, when a woman has low LH levels, for example, you may see the LH rise up in preparation for ovulation when she is taking the herb. However, in other situations, such as menopause or PCOS, where LH is high, you may see it reduce. And in other situations, it may have no effect at all.

New research suggests that vitex likely binds to different types of opioid receptors that are found within in the brain.11 According to one study, vitex affects natural beta opioid levels, with an increase of 105 percent after just five days of treatment.12

The opioidergic system is very important, as it controls certain actions of the reproductive system. It inhibits the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, reducing the negative impact of this axis on GnRH, LH, and FSH.13 In other words, it stops your brain from triggering the production of stress hormones. And the most important action it has with respect to female hormones, and especially to women with PCOS, is that opioids slow down pulsing of the hypothalamic master hormone GnRH.14

Now, let’s think back to the problem with GnRH that is present in women with PCOS. GnRH pulses too fast. The role of progesterone after ovulation is to slow that pulsing. When the pulse slows down, the pituitary starts making FSH to grow an egg and shifts away from making LH. Women with PCOS don’t have enough progesterone to slow the pulsing down. In addition, they appear to have hypothalamic resistance to progesterone.

Recent studies have found that women with PCOS have clear dysfunction of the opioid system of the brain.15 This is the exact system that vitex works on. Insulin resistance in PCOS further aggravates dysfunction of the opioid system. So in women who are insulin resistant, the opioid system’s function may be significantly improved by working on that factor first.

Overall, vitex helps regulate the hypothalamus by slowing down its rapid pulsing and allowing FSH to take predominance. FSH is what allows a follicle to grow and produce estrogen, causing a surge of LH that triggers ovulation. So when we think now about what vitex does, and about how LH and FSH work, it isn’t as simple as raising one hormone or another. Vitex can help get the concert of hormones back in order, so they can start to self-regulate once again.

We now know that vitex can work on the dopaminergic system of the brain and reduce prolactin levels (which, if high, inhibit ovulation). We also know that it works on the opioidergic system, slowing GnRH pulses and reducing LH. When used in the right way, vitex can be exceptionally beneficial for women with PCOS. So again, you can tell if you are stuck in a state of fast GnRH pulsing by testing your LH, which will be high much of the time.

Vitex’s opioidergic effect is likely part of why numerous studies demonstrate its efficacy in reducing the mood-related symptoms of PMS and improving painful periods. I believe this system may be one of the reasons that women with PCOS are more prone to depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders. There are different ways of using vitex, but I would like to show you the two main ways that I use it in my practice.

The first is when a woman has moderately high LH and is ovulating, but ovulation is delayed (for example, women who have a thirty-two to forty-five-day cycle), I use vitex only in the luteal phase. I prescribe it in the morning as a single dose. The reason for this is that prolactin follows a diurnal circadian rhythm—with highest levels during the night when it is dark. On rising, prolactin should drop. Women who have high prolactin often have difficulty with this circadian rhythm and can be best assisted by reducing prolactin in the morning, following the natural circadian rhythm.

The reason I use vitex only in the luteal phase is to encourage the slowing of the GnRH pulse and to reduce LH and increase FSH to prepare for the next cycle. I find that once the slow pulsation is established at the start of the cycle, the pituitary will respond well to the subsequent rise in estrogen. I find that this often takes several cycles to have full effect. Typically four to six months on vitex will help to establish good regularity.

The second way I use vitex in my practice is for women who have longer periods of time between cycles or who have complete amenorrhea. I prescribe it for them daily. In these women, GnRH pulsing is fast on a continuous basis. Therefore, vitex can be beneficial when used in a continuous manner to break what can sometimes be a stubborn hormonal pattern.

The method of dosing is the same. It is taken in the morning. Once semi-regular ovulation is established and ovulation can be detected, I then switch over to the first method. Once regular cycles have occurred for three cycles, I will stop the herb.

I typically dose vitex at 1,500 mg in the morning (typically a 6:1 or 5:1 extract). Both tinctures and dried extracts can be effective. Choose them carefully, however, as many commercial products do not have enough of the flavonoid components to effect the mu-opioid system, including apigenin, luteolin, isokaempferide and casticin. The diterpenoid components of vitex work to reduce prolactin through the dopaminergic system, so these are important as well. It is unfortunate that there are many inferior herbal products on the market.

These herbs are another powerful combination for women with PCOS. Typically, they are used throughout a woman’s entire cycle and are often helpful for those with slower metabolic function and insulin resistance. Together, these two herbs have been found to reduce testosterone, reduce LH, improve the LH/FSH ratio, increase ovulation rates, increase the granulosa’s production of estradiol, and increase luteal phase progesterone. Dosing typically ranges from 6 to 10 grams per day in divided doses.

Angelica root (Angelica sinensis), or dong quai, is an herb with a long tradition in traditional Chinese medicine. It is a hormonal regulator and is a phytoestrogen that can bind to estrogen receptors and weakly activate them. This can be beneficial for women with PCOS who are deficient in this key female hormone. It has been shown to activate estrogen responsive genes within the reproductive organs, turning on mechanisms that may have lain dormant. For women with PCOS, I have found it to be an excellent herb, particularly when used in the follicular phase of the cycle. In addition to this, dong quai has been found to increase the generation of red blood cells in a process known as hematopoiesis. As such, for women who have very light periods, or iron deficiencies in addition to PCOS, it may be an ideal hormone-regulating herb. Dong quai is often dosed at 200 to 500 mg, three times daily.

Peony and licorice work well for lack of cyclicity with androgen excess predominance, whereas peony and cinnamon are used for lack of cyclicity with insulin resistance predominance and poor circulation. Both combinations can be used for the duration of your cycle.

For women who have predominant hypothalamic pituitary dysfunction, I have often used variations on the following based on time of the cycle. This is a more advanced herbal prescription and often requires the support of an herbalist or a naturopath. There are innumerable other variations that can be used depending on your needs. However, this would be best assessed by a practitioner who can devote adequate time to your entire case.

The following can be used during the follicular phase:

The following can be used during the luteal phase:

In my clinic, I prescribe tinctures and will customize the amounts and vary the formulas. You can purchase quality tinctures from reputable local herbalists or through your local naturopathic doctor. You can have the tinctures compounded for you, or you can mix them yourself at home.

The dosage for these tinctures is one teaspoon in the morning and one in the evening. Typically, many herbs are made in a 1:4 extract (meaning one part herb with four parts solution). If your extract differs concentration-wise, please adjust your dosage accordingly. For example, if you have purchased a 1:2 extract, you should reduce your dose by approximately half.