A GREAT WAR COMES

Tanga

During my lifetime I have seen the world grow very small, to where a man is insignificant.—Pieter Krueler

After hostilities ended, Pieter Krueler and Koos Ley found themselves put into a displaced-persons camp, and after two months there moved on to a boys camp and school. They remained there for a further nine months, after which Krueler passed his examinations for completion. After discovering that their family homes had been burnt to the ground and the land confiscated by the new government, the boys struck out for more adventure.304

The decade following the end of the Second Boer War proved hard for Pieter Krueler. The new governmental structure, especially after the creation of the Republic of South Africa in 1910, was not always friendly to the non-English speaking population. The inherent racial attitudes were cemented into future laws, creating a caste system according to race and ethnicity.

Many of the once-prosperous farms of the Transvaal and Orange Free State soon became British corporate land holdings. Many of the farms seized during the war were not returned to their owners, even if they had survived the war. Many properties were confiscated by the British, and then turned over to companies holding interests in gold and diamond rights.

Krueler and Koos Ley returned to the Orange Free State and worked as cattlemen until 1905. Following another year in German Southwest Africa as stockmen, they returned to South Africa to try to find more gainful employment. In 1906 they were both hired at one of the DeBeers mining operations as camp guards. The pay was adequate, more than they had made as cattlemen, although Krueler knew that being a guard was not his life’s ambition.305

Long after his death in 1902 Cecil Rhodes’s corporate interests, especially gold and diamond mining, were pursued with ruthless energy, and little regard for safety. There were no laws regarding wage minimums and safety conditions for the several mines owned by DeBeers—profit was paramount over human rights and safety.

Many men, black, white, and those from the Indian subcontinent, worked and died in these unsafe conditions. Pieter Krueler was one of those young men working in those mines of despair. Peter Abrahams ably chronicled conditions in the mines in the mid twentieth century in the novel Mine Boy.306 This book is worthwhile reading on the subject, and illustrates the racial divide that existed in apartheid South Africa’s mining industry.

At this time, the majority of the workers were whites, which would change later. While many were paroled convicts, the vast majority of skilled laborers were Boers or ex-soldiers. These were skilled laborers: demolition men, engineers, support and structural specialists, and drill technicians.

The recent invention of the hydraulic drill enhanced the pace at which gold and diamonds could be mined. The income potential for these men was ten times that of the manual laborers. Additionally, the white workers were allowed to roam in and out of the various mines between shifts. The black Africans were not given that freedom. “Armed guards were positioned around the heavily fenced compounds, where the workers leaving the mines were manually strip-searched and inspected, all in the prevention of smuggling the raw diamonds or gold nuggets out of the mines.”307

While Krueler described the mine at which he worked for three years, he declined to disclose the exact name and location, stating that the men signed nondisclosure statements that prevented them from discussing mining operations and company details. However, he did relate the conditions, his work, and what he witnessed. “It was a worse treatment of men than I ever saw during any war,” he commented.308 What follows is a chilling indictment of Cecil Rhodes and the greed of the diamond mining industry as it was during the first quarter century in South Africa.

According to Krueler, in 1906 there was a cave-in at his mine. One of the deep shafts had a wall collapse. The cause was unknown, but possibly more than eighty men were buried alive just after the morning shift had started. Krueler described the conditions of the mineworkers:

The one thing that you must remember was that these operations were not regulated by the government. That means that accidents did not have to be recorded, and I do not know of any deaths that actually reached the government in Pretoria.

The mine managers and owners knew of course. They kept a monthly report on injured and dead men so as to go about hiring replacements. There were no safety standards, not like today. Those men trapped were not even saved. The shaft, which had not been sunk in a very productive area, was simply written off. The hole was filled, and the newer south shaft that was being built was continued. There was not even a memorial ceremony, not even for the white miners, who were always Boers.309

Guards at this particular mine served in three areas: watch towers at four corners of the compound on four-hour rotating shifts armed with rifles; outer-perimeter guards, also armed, patrolled the double fence line in pairs with dogs; and inner-perimeter guards who were unarmed except for large truncheons and monitored the inside of the camp. All persons coming and going were to display their working identification card.310

Koos Ley and Pieter Krueler manned towers at opposite ends of the camp, which covered almost twenty acres. The entire time he worked as a guard there was not an incident that required the discharge of a firearm. When word reached them that the mine managers were looking to hire a few more demolition experts to open up new shafts and expand the tunneling effort, the two friends volunteered for the higher-paying work. Guards made the equivalent of $600.00 U.S. per month, which was an outstanding sum in those days, considering that the company provided rudimentary housing at no cost to white employees.311

Black miners lived in abject squalor, often eight or ten to a bungalow. Meals were provided by the company, although in most cases it was barely at a subsistence level. Married men were expected to consider themselves as single men; no families were allowed. The great irony was that the black workers had armed guards around their bungalows, whereas the whites did not. The company owners feared a black uprising, such as had happened at another mine some years before.

Having been trained in the use of dynamite and nitroglycerine during the war, the two boys knew enough about demolition and soon began earning five times what they had as guards. However, along with the higher pay came a much greater risk. The deepest shaft was almost eight hundred feet below the surface. The hydraulic engineers had managed to insert a pump to drain the water that continually seeped through the walls and up from the floor. The deeper they went the more water they struck:

As you entered the mine, even on the hottest day, the lift carried you down powered by a truck motor. It was a slow process, and you hoped like holy hell that damned truck motor did not break down. Once you were halfway, you were actually quite cold. The dampness set in. Most people do not realize that this was actually a coal mine that had diamonds in it. The coal was brought up and used as fuel for running the camp stoves, and even sold to various other companies. The large pieces of black rock were placed on a conveyor that had a large hammer operated by steam that smashed the rocks. The workers up top would pick through the rubble, and extract the rough diamonds. Workers below used hammers and picks to dig the rocks out. Even the whitest of men came out looking as black as the coal they dug.312

Krueler and Ley finally left the mining business in 1910, just as South Africa became a republic within the British Commonwealth. However, despite this departure, the world of mining would see Pieter doing this dangerous work again later in his life. Krueler decided to try to gain entrance to one of the new up-and-coming universities. In Johannesburg he took the entrance exam and passed. In the interview process, however, the three members on the matriculation board seemed more concerned with his “non British” background than his stellar test scores.313

In Pretoria he again went through the examination process and even succeeded in passing the first oral interview board. Upon receiving verbal acceptance he was later called into the office of the senior lecturer. His application had been reconsidered; he would not be able to attend.314 This second slap in the face probably engrained his hatred of the British-mandated education system. He was learning first hand that discrimination was not restricted just to the blacks and coloreds in their own homeland.

Koos Ley had decided to go back to his native region and look for work. After his university disappointment, Krueler decided to follow him. Five months after they had last parted, they met in Pietermaritzburg, working for a cattle distributor. This work lasted for four years and carried them all over southern Africa.

Due to their many trips and amount of time spent in German Southwest Africa, they made friends with the local German soldiers in the garrison, as well as a few of the diplomats, businessmen and their families. The Germans seemed quite keen on hearing their stories of the battles they fought against the British. Krueler thought that their interests went far beyond general knowledge. The Germans wanted to know about tactics, schemes of maneuver, and their employment of crew-served weapons.315

There were many Boers who had fled South Africa rather than live under British rule, along with “15,000 Indians, Arabs, and Goanese. German Schutztruppe (German colonial forces generally consisting of volunteer European officers and NCOs and locally recruited enlisted men) numbers in East Africa alone numbered 260 Europeans and 2,472 Africans.”316 The numbers of Boers, the last of the “Bitter Enders,” was not and may never be known. However Krueler said, “I know that we had at least three full companies of Boers, many from Natal, and some of my brother Transvaalers. There were also quite a few Free Staters. Unfortunately, I rarely had the opportunity to serve with them. It would be very interesting that Boer would be fighting Boer in the Great War coming.”317

Ley and Krueler were in Windhoek during the month of August 1914, after another of their treacherous crossings of the Kalahari Desert. Just before the sun set on the last day of the month one of their German soldier friends came into their tent and announced that Germany and Britain were at war.

Krueler remembered, “This was something we could not believe, so I asked him again. Are your certain?’ He was very insistent, and even handed us a print from a cable sent to the German garrison commander from the senior German diplomat. I knew then that we were at war. The next question was what do I do next? Ley and I decided that we could not fight for the British. The next day a German major whom we knew came to see us. After our talk, we knew that we would fight for the Germans. At least they were not trying to take our land away and starve our people to death.”318

Krueler and Ley had many friends amongst the Bushmen, Herero (despite many following the British), Ovambo, and Hottentot peoples, and this combined with their battle experience and knowledge of the terrain made them quite valuable indeed. The Germans wanted to recruit African indigenous forces as auxiliaries, but language barriers and the locals’ natural mistrust, primarily of the ethnic Bantu peoples for all Europeans, were often serious obstacles. According to Krueler: “Whichever stick was presented to the blacks by Europeans, the Africans always had the short end of it.”319

The Germans hired Krueler and Ley as indigenous troop leaders, handling the recruitment and translation issues regarding the black recruits, as well as mapmakers to the German military intelligence command. Edmund Dane, in his book British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific 1914–1918, states the following numbers for indigenous soldiers, with both the British and Germans vying for their services: Herero eighty thousand and Ovambo thirty thousand able men.320 The Hottentot numbers were never fully known, although there were an estimated fourteen thousand men at arms working with the Germans, according to Krueler. The history of interaction between the Europeans and tribal groups were as diverse as their allegiances.

The Hottentots favored the Germans due to their support during several internecine tribal wars with the Herero between 1864 and 1870. In 1905 the Herero and Germans fought a short war against each other, with the surviving natives choosing the harshness of the Kalahari to German rule. That event placed the Herero firmly in the British camp, with the Bushmen largely unaffiliated. The Germans found that the Hottentots, when properly trained and led, were excellent with modern weapons and tactics. The Ovambo were a unique collective, perhaps even more secretive than were the Bushmen. Their allegiance was never certain.

Before the war the Imperial German government had been one of the first entities to openly acknowledge the independence and statehood of South Africa. This made perfect sense on both a political and military level. Even though the British were still firmly entrenched within the country, the Germans always looked upon the non-British population as a potential ally. Krueler and Ley were to be conduits for fostering that relationship.

Another problem the Germans in Southwest Africa faced was that their presence was actually more of a police force as opposed to a truly war-ready military contingent. The Germans were wary of British strength in southern Africa, as well as East Africa, where the Germans also had a colony. The Germans felt that they had a strong alliance with the Boers, given their recent history with the British. For the most part, however, this would prove to be a delusion.

What the Germans did not count on was the fact that Botha and Smuts had both mended their fences with the British, once their antagonists, Kitchener and Milner, had been removed from the equation. As stated by Dane: “It will be seen therefore that General Botha held the decision in his own hands, and unfortunately for their projects the Germans had reckoned without him.”321 The oversight was fatal.

Not only were Generals Louis Botha and Jan C. Smuts men of military experience who could not fail to see the meaning and intention of German measures in Southwest Africa, they were statesmen capable of taking and acting upon long views. To them, as to every reflecting man, it was clear that German policy towards the natives involved a great danger to the British Empire, and perhaps even South Africa.322

Krueler and Ley met the chief of police for the district, a fellow named Paul Gaisser, who informed them that there were several South Africans who had joined the police and colonial military. Most worked as translators and trackers, which were always skills in high demand.323

As war developed, Krueler trained on German explosives, taking an intense two-week course in the use of the newly developed land mines. These were powerful new weapons, a revolution in antipersonnel weapons that would come to plague mankind to the present day. One type was a metal “contact mine, a great iron case packed with dynamite exploded by a rod,” while the other “was electrical, fired by a concealed watcher from an observation post. Both were employed on a lavish scale.”324

By the middle of September 1914 the Boer volunteers had completed basic standardized training, and the selected group, numbering some 160 (according to Krueler) and many of the local volunteers for a total of almost 500 men, were to be relocated. These volunteers, including Pieter Krueler and Koos Ley, joined a group of Germans commanded by a young Leutnant (second lieutenant) Julius Spalding, “a fine Jewish officer and a man” the two Boers liked very much. He did not drink and he did not smoke, so one of the missions the two men had was to discover what vices he did have.325

They boarded a German ship and disembarked at Dar-es-Salaam, the German headquarters for colonial operations and main communications center, to support the German East African Protective Force. Krueler gave his recollection of the journey: “I had never felt so ill in all my life, up to that time. Every one of us, almost to a man was throwing up. Seasickness was an experience I decided never to repeat again. For the entire week, it was impossible to sleep, eat, or keep even water down. I just wanted to die.”326

They arrived on September 29, and upon collecting their packs and weapons, they were supplied with two hundred rounds of ammunition per man, quinine, salt tablets, two liters of water, ground millet and dried beef or pork, mosquito netting, and lubricating oil. They loaded up onto trucks and after three days jumped out at Tanga, in anticipation of a British attack by sea and or land from Kenya. The trucks then left to return to Dar-es-Salaam to retrieve more of the soldiers, and when ready all were staged for departure with the troops who had arrived by train from Moshi.327

Krueler and Ley were assigned to the 17th Company and with the other new men formed up for an address. The British were expected to land at Ras-Kasone, east of Tanga or even Longido, threatening the German right rear.328 This group of men was to move out immediately to the company as reinforcements. The Germans and their African auxiliaries could see the lights of the British ships just offshore. What the future held, no one knew.

The governor of German East Africa, Dr. Heinrich Schnee, according to Professor Hew Strachan (The First World War in Africa), “was a lawyer and professional colonialist… the antithesis of the soldierly types required for the job in the early days of the conquest.”329 Lt. Col. (later Lt. Gen.) Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck and Doctor Schnee, by all accounts, had a very uneasy relationship. The consummate politician versus the ultimate soldier, two men living in the same world, each with his own personal desires, and each feeling he knew the best course of action to take.

Schnee was a pacifist bureaucrat who felt that détente could solve any problem. Lettow-Vorbeck was a professional soldier, son of a general and a veteran of the Boxer Rebellion in China (1900–01), as well as many other situations throughout German colonial Africa and the world. He was far more pragmatic. Diplomacy and discussion were fine, as long as one had the men and guns to enforce his political will should diplomacy fail.330

The British perspective on the Tanga operation comes from the memoirs of Richard Meinertzhagen, a British intelligence officer in East Africa at this time: “The Germans appeared to be keeping to their side of the border with British East Africa but had concentrated their troops in the Moshi region with an advanced post placed near Taveta to keep tabs on their adversaries. The Germans were smart. They had concentrated their efforts, whereas their enemies had spread themselves out all over the place with no strong, central reserves. The Germans had the power of the initiative.”331

Part of the German forces, with 80 Germans and 600 Askaris at Longido and Namanga, was under the command of Major Georg Kraut, who was rapidly earning a reputation as a premier guerilla fighter, while only about 125 German troops actually occupied Tanga proper. His actions completely reduced the British opposition, forcing them to retreat, and he relocated to Moshi once he realized his position was too exposed. His small force acted as Lettow-Vorbeck’s eyes and ears.332 Lettow-Vorbeck rapidly began moving his troops from Kilimanjaro to the coast.

The British and Germans had a tenuous “gentlemens agreement” regarding any British attack, and any German offensive actions. Once HMS Fox, under Commander F.W. Caulfield was offshore, a message was forwarded to the Germans for their surrender.333 Naturally Lettow-Vorbeck politely refused, thus the stage was set.334 This interlude allowed the German commander time to bring more of his troops into the area.335

On the evening of November 2 the men had just finished their four-hour march into Tanga from the railhead when Krueler and Ley were told to scout ahead and observe when the enemy attack came. Krueler was sent forward with Ley to observe the British ships and report back, which they did from the vantage point of a roof while covered by mosquito netting. At dawn on November 3, the British landed at Longido and this was reported immediately back to Krueler’s command.336

Krueler called out his observations as the boats and men started to come ashore, the runner taking his information back to the company. This allowed the Germans to place their blocking force effectively, allowing the streets connecting to the shoreline to become channeled killing zones if necessary. According to Meinertzhagen: “It’s a fair bet that German intelligence scouts must have observed this entire episode.”337 Once the battle started Krueler and Ley scrambled off the roof and headed back.338 Meinertzhagen had been correct.

The few shells thrown into the town from the ships and the bullets from the British Lewis guns kept some of the Germans pinned down, and random enemy small-arms fire wounded some of the new arrivals. The initial engagement was brief, but enough of a reality check to sharpen the wits of any man, and the British lost three hundred men on the beach the first day.339 The German 6th Field Company was placed as a holding force east of Tanga covering a large area. The 17th Company commander (who was also the district commissioner), a Lieutenant Auracher, sent word to his platoon leaders, and Lieutenant Spalding gave his sergeants their orders. As Krueler remembered:

I was quite surprised when Spalding came to me and told me I was a sergeant, and he gave me a squad of fifteen men. This was a collection of five Germans, four Boers including myself and Ley, and three black soldiers, who I had known for some time. They were all good men. Ley asked me, ‘what am I supposed to do?’ I told him that his job was to not let me get shot.

Spalding told us that there were reports from the 6th Field Company of enemy infiltrators trying to come around behind us from the north and west. We were to run a patrol due west and north and see what we could find. We took off and made about a six-mile patrol, meeting a few of the German and colonial troops, but there was nothing to report so we returned before dawn. Once we arrived back we were ordered to accompany Spalding to meet with Hauptmann [captain, later major) Baumstark, the acting battalion commander.340

The morning of November 4 saw the British renew their attack into Tanga once the rain had subsided, having landed the night before unopposed but not unseen.341 According to Meinertzhagen: “Not 600 yards out of Tanga, the Germans suddenly opened fire. .,” which would have been the machine-gun crew under Spalding. They had prepared their weapon and field of fire along the most likely avenue of approach. The battlefield was a steam bath; stifling heat and heavy humidity.

Writing about this battle Meinertzhagen said, “[I] took aim at a man with a fine face, but uncharacteristically, [I] missed.” The man Meinertzhagen claimed to have almost killed was Lettow-Vorbeck himself. Ironically, the two men would become close friends after the war.342 Such are the fortunes of war, and had Lettow-Vorbeck been killed the history of the war in Africa very likely would have been quite different. However, Brian Garfield in his book The Meinertzhagen Mystery disputes the story, although Lettow-Vorbeck supported the story from his own experience of the event, and his discussions with Meinertzhagen.

At this time Krueler received new orders:

Ley and I were told that the 16th and 17th Companies were to be integrated into a single company, with all troops in the area reinforcing Tanga. The 4th and 9th Field Companies were on the way also, although 7th and 8th Rifle Companies were more under strength. We were told that six thousand enemy troops had landed, outnumbering us considerably [data supported by Dane343]. As a sergeant, I was told to take twenty men, and one machine gun to join the 8th Rifle Company and report to their commanding officer. They apparently wanted men with extensive bush experience, and once word was passed that some Boers with experience were in the ranks, Lettow-Vorbeck himself wanted all of us. Soon all of the South Africans would be placed in the same command within the 7th and 8th Rifle Companies, as far as I remember.344

The memoirs of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck outline this action in some detail, details that would have been unknown to Krueler at that time. Lettow-Vorbeck knew that the British landing in such large numbers posed a great threat to the German-held Northern Railway in Tanzania, which was then part of German East Africa.

According to Lettow-Vorbeck’s plan the preferred method of operating was to fight head on in company-sized formations, while using the auxiliaries as scouts and raiding parties. Protecting the railway was crucial, as Lettow-Vorbeck said: “It was too important to prevent the enemy from gaining a firm footing in Tanga. Otherwise, we should abandon [to] him the best base for operations against the Northern territories; in his advance, the Northern Railway would afford him an admirable line of communication, and he would be enabled continually to surprise us by bringing up fresh troops and stores. Then it was certain that we would be unable to hold the Northern Railway any longer and that we would be obliged to abandon our hitherto so successful method of warfare.”345

With their platoon, Krueler and Ley reached headquarters and handed over their papers on November 4. They were to support the actions of the Askari Company, the “Bushmen” as they were called, as the order to move into Tanga proper once the initial British advance had stalled, was passed down the ranks.

Krueler and Ley reported to their new commanding officer along with their platoon leader, Lieutenant Spalding. Upon meeting Captain Tom von Prince they were given their orders, relieved of the water-cooled machine gun, and informed that they were “outnumbered twenty to one.” The two European companies prepared to march into Tanga and into the heart of the enemy assault, as the Askaris had already moved forward.346

The Germans and their allies were facing a unique opponent: the British North Lancashire Regiment under Colonel Charles Edward Arthur Jourdain. The unit was, despite its name, a collective of white soldiers raised in India, numbering some eight hundred men, well below regimental strength and more the size of only two standard battalions. Intelligence also claimed that the Indian Brigade “Kashmir Rifles” was in support.347 The British unit was well seasoned and battle tested, full of veteran officers and NCOs, although the quality of the Indian conscripts was in question.

“We could see many of the Indians scattering, some dropped their weapons, and nearly all running away after the first few exchanges of gunfire. They were actually leaving their comrades in the lurch. It was incredible,” Krueler said.348 Meinertzhagen recalled the same event himself, where fear and cowardice were rampant, and he stated in his memoirs that he actually had to kill two of them himself as they deserted.349 However, not all of the Indian sepoys turned and ran. Many died moving forward, or lay wounded unable to continue. The Gurkhas of the Kashmiri Regiment would earn the respect of their enemy. Even Lettow-Vorbeck was shocked at their fighting spirit and almost magical abilities.

Thirty-year-old Sgt. Pieter Krueler, thirty-three-year-old Koos Ley and twenty-four-year-old Lt. Julius Spalding collected the platoon and checked their equipment. After fewer than ten minutes they moved toward the heart of what would be one of the first major battles of the Great War in Africa. They would attack from the south, supporting the west-to-east attack by von Prince and Captain Alexander von Hammerstein.350 Hammerstein had become angry at one of his Askaris deserting under fire, and threw an empty beer bottle at him, striking him in the head and knocking the man out. Soon all of the indigenous troops were throwing empty bottles at the enemy troops, primarily the Indians, most of whom abandoned their weapons and ran back from where they came.351 Garfield wrote, and Krueler confirmed, that the Askari morale was quite high.

The gunfire could be heard just to their front, so the platoon quickened their pace. They moved through the forests, where stray bullets snapped and whined, probably British and German alike. No one knew.352 What was known was that most bullets did not have a specific destination, but were simply addressed “to whom it may concern.”

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck recalled the event in his memoirs: “At this time, in the dense forest, all units, and in many instances friend and foe, were mixed up together, everybody was shouting at once in all sorts of languages, darkness was rapidly setting in; it is only necessary to conjure up this scene in imagination in order to understand how it was that the pursuit which I set in motion failed completely.”353 Krueler’s comments seem appropriate:

Once we hit the trees, trying to avoid the bullets slamming into them, the unit became dispersed. We came across a few Askaris with Indian prisoners. I had met a few Indians in South Africa working in the mine, a very interesting group of people. I could never fathom not eating beef, which was what many of them held as an abomination. The Muslim Indians had no problem with that, but they would not touch pork. I wondered, looking at these men, which group they belonged to.354

Krueler’s group pushed through the night until they broke through the forest of rubber and fruit trees, then Spalding had them set up a security perimeter. Krueler and Ley went forward as a scouting team, and managed to get inside the city. They watched the Askaris and a few German units marching back west, which they could not understand. Krueler asked one of the German NCOs what was going on. “He said that an order had been passed to return to their starting points, directly from headquarters.”355 Lettow-Vorbeck’s memoirs also mentioned this misunderstanding, and upon hearing it, he ordered the troops right back to Tanga.356

As they entered deeper into the city, it was strangely quiet, and almost completely empty. The smell of death on that early dark morning of November 5 told the tale. They found large piles of British and Indian dead stacked, obviously by their own troops. “There must have been hundreds of them, there was no way to count,” Krueler said.357

Lettow-Vorbeck stated, “A senior British officer, who had accurate knowledge of the details, told me later, on the occasion of an action in which he stated the English casualties to have been 1,500, that the losses at Tanga had been considerably greater. I now think that 2,000 is a low estimate.”358

Krueler and Ley returned to Spalding and reported what they saw. At that point, the Germans moved en masse into the city, occupying several of the white-painted stone houses. There were a few Germans and Askaris, along with several British and Indian soldiers in a couple of the houses, their heads and arms swollen from multiple bee stings.

Apparently, from what can be gathered from Krueler’s story and Lettow-Vorbeck’s notes, one of the German machine gunners had fired into the town and struck at least one if not more beehives. The angered insects attacked everyone, choosing no allegiance to one side or the other. Lettow-Vorbeck remarked how one British officer inquired as to whether or not “we had used trained bees at Tanga, but I may now perhaps betray the fact that at the decisive moment all the machine guns of one of our companies were put out of action by these same ‘trained bees’.”359

Krueler and Ley’s men collected more than twenty British and Indian prisoners, who were marched to another empty house and placed under guard. They were amazed at how many had swollen arms, legs and faces from the bee stings. By dawn over eighty enemy soldiers were packed inside the small structure. Krueler remarked about one British officer’s attitude towards his “allies”: “This British officer, a young lieutenant I think, seemed quite displeased at being with the ‘wogs’ [worthy oriental gentleman—a persistent and extremely pejorative Briticism from the nineteenth century]. I found his attitude somewhat interesting, since I had never judged a man by his skin color. Bravery and service are not dependent upon a man’s race. I threw him and some of his men in with the ‘wogs’ he detested so. He did not seem very happy.”360

This British officer was not unique in his assessment of his African and Indian comrades. Byron Farwell relates the attitude of the British troops’ commanding general, Arthur Edward Aitken, regarding his views of the African native troops: “The Indian Army will make short work of a lot of niggers.”361 The height of the irony was that these “niggers” had just defeated their British “racial superiors” and their Indian troops, who were at that time sitting in captivity. Krueler insured that black and white shared the same discomfort and he had black Askaris search their British prisoners to reinforce their humiliation.362 Aitken was later reduced to colonel, retired on half pay, and is virtually forgotten by history.

Soon a German officer with a small squad arrived. He was shocked at the conditions in which the British officers were housed, most of them wounded and thrown together with the enlisted men; British, African, and Indian collectively. The first person he saw was Koos Ley, and as remembered by Krueler:

This German guy simply began tearing into Koos, as if he were to blame for the entire dismal circumstance. Koos was in a state of shock, and he looked at me. I walked over and saluted the captain, and asked if I may be of assistance. He saw my rank, and knew I was not German, as we did not wear standard uniforms, just our bush gear and hats. He then turned his fury upon me, and I was just about to drop this man with a butt stroke to the head. He demanded my papers, name, unit and commanding officer.

I gave him the information, and then I told him that if he was unhappy with our performance, seeing we had just captured almost a hundred prisoners, secured five or more blocks and the main road in the city, as well as capturing a massive stockpile of enemy weapons, which I pointed to, then I would be pleased to inform all Boers and others that our services were not required any further. He then ordered another sergeant to arrest me, and at that time the fifteen Boers, all of whom had fought the British at places such as Ladysmith, Spion Kop, Colenso, and other battles, raised their weapons against the Germans. Everyone heard the clicks of bolts chambering 8mm Mauser cartridges.

At that time Spalding ran forward, saluted the captain, and pulled him aside for a talk. After almost ten minutes, I think the captain looked at us, half-assed saluted us, and then walked away with his men, taking the prisoners off our hands. I asked Spalding what happened, and he simply said: ‘I just told him who you men were, where you had been, and what you had done, and if he wanted responsibility, he should discuss it with Captain [later Major] Baumstark and I.’

This was the kind of officer Spalding was, and I admired him; although he was a young officer, he was a good man.363

Krueler was to learn after World War II that this fine officer’s family, for the most part, perished during the Holocaust. “Such stupidity. Such a waste. I often wonder why God created humankind. We are such ignorant, unappreciative and undeserving creatures.”364

It must be noted that in the wake of National Socialist Germany under Adolf Hitler from 1933 to 1945, where the racism established by the Nuremberg Laws became “law,” and made the later South African policy of apartheid seem almost polite, Lettow-Vorbeck was never a racist, and he would tolerate no such idiocy within his ranks. What was perhaps Lettow-Vorbeck’s greatest asset besides his great intellect and experience was his ability to garner the respect and even admiration from his subordinates.

According to Brian Garfield: “He was fond of tactics and wise about strategy, but war did not delight him. All the same, he would prove to be the outstanding guerrilla leader of the twentieth century, a feat he accomplished in part by leaving quite a few prejudices behind: he appointed Africans as officers, sometimes over white subordinates; he said and believed ‘We are all Africans here.’ Without fuss and without seeming to notice it he created the first racially integrated army to serve in modern warfare.”365

In an interview the author conducted with SS Lt. Gen. Karl Wolff in 1984, shortly before his death, he said, “Himmler told me that the Fuehrer was quite upset that General Vorbeck would not support his campaign for the Reichstag. He was even more upset that, as a holder of the Pour le Merite, he did not give his support to our great cause. Hitler liked recruiting the heroes of the Great War, such as Goering, Keller, and others. It gave him legitimacy. I never met Vorbeck, but I knew everything about him. He was known by Reinhard Heydrich as a ‘Jew and black’ lover. I was very surprised that he survived the war. I think his medals and fame saved him.”366

Indeed, as written by Byron Farwell (The Great War in Africa), Lettow-Vorbeck “… cared no more about race differences than differences in rank when it came to finding the best men for the work at hand. He put Africans in companies of white Schutztruppen and whites in the field companies of blacks until they became identical, thus creating the first racially integrated modern army.”367

Farwell also wrote, and Krueler agreed: “Strict but fair, he inspired an exceptional loyalty in his African troops (Askaris).” Aaron Segal (as cited in Farwell) said, “one of his great abilities was to take the African precisely as he found him, without any transfer of European mores. He seems to have been unique among European officers in his conviction that ‘the better man will always outwit the inferior, and the color of his skin does not matter’.”368

Krueler was then ordered to ensure that the wounded prisoners were carried west to the makeshift field hospital, securing the word of honor from the British officers that they and their men would not violate the truce. This would ensure that Germans and colonials could get the wounded to safety. A few hours later Krueler and Spalding were told to report to Captain von Hammerstein, whom Spalding apparently knew. Hammerstein was also Jewish, and apparently “an outstanding officer.”369 The British wounded were carefully placed under a large tent erected to keep the men out of the hot sun as the morning mist began to burn away. The flies began to be terrible as well.

The captured weapons had been brought forward and Lettow-Vorbeck, the commander, stepped out to see the men and look at the wounded. The men snapped to attention as Lettow-Vorbeck casually walked the line, looking at the condition of his men, asking questions, and offering encouragement, especially to the colonials. Krueler explained the event:

The colonel looked at us, in our odd looking uniforms, and asked us in German who we were. I responded that we were from South Africa, which peaked his interest, as South Africa was a British ally. Once told we were Boers, and had fought the British, he smiled and took his hat off. He then spoke with Hammerstein and Spalding, and Spalding came to me and said that I was to accompany Hammerstein and assist with the hospital accommodations. I saluted, shouldered my weapon at the sling and took Ley with me. There were so many wounded, some so horribly, that I felt sorry for them. Later that afternoon I was called forward, and Captain Hammerstein took my field glasses and looked down the road. He could not believe what he was looking at.370

Hammerstein saw a British soldier carrying a white flag. The standard-bearer was Captain Richard Meinertzhagen, who carried a letter addressed to Lettow-Vorbeck, requesting care for the wounded and bringing medical supplies. The British were demoralized, their Indian conscripts had fallen apart, and the pride of the British Empire had been slapped and beaten by mostly black soldiers.

Meinertzhagen met with the future German general, handed over his request, and then departed.371 On the way back an auxiliary (according to Peter Capstick in Warrior: The Legend of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, it was an Askari; Farwell claims it was a sepoy) fired at him from close range, the bullet passing through his helmet and singing his hair. Meinertzhagen took the man’s rifle and killed him with his own bayonet.372

Meinertzhagen managed to negotiate a removal of the British wounded with Lettow-Vorbeck, under the condition that these men would never fight in East Africa again. The weapons and supplies were to be abandoned, the wounded taken aboard the ships, and the able-bodied British soldiers were to walk into German captivity.373 Meinertzhagen had his own opinion of his troops and superiors before the battle, thus explaining their failure: “They constituted the worst in India, and I tremble to think what may happen if we meet with serious opposition. The senior officers are nearer to fossils than active energetic leaders.”374

Krueler and Ley assisted the British and Germans with getting the wounded to the beach for evacuation.375 He had an opportunity to speak with the interesting Meinertzhagen. Upon discovering that he was a Boer, Meinertzhagen said, “You were probably lucky I was not there, sergeant, and you will be considered a traitor back home,” to which Krueler replied: “I think you are right sir, I am glad we did not meet before. I would hate to have buried such a brave man who cared this much about his men. I am not used to that in a British officer.”376

Despite this, they clearly understood each other well. Decades later, they would meet again in South Africa, and again in Kenya where Meinertzhagen retired, forming a lasting friendship until Meinertzhagen’s return to England and his death on June 17, 1967. It must be stated that for decades Richard Meinertzhagen was revered by military and political leaders, including Winston Churchill. However, Brian Garfield, in his 2007 book The Meinertzhagen Mystery: The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud, has cast great doubts about the voracity of Colonel Meinertzhagen’s assertions regarding his career in general, and his actual exploits during Tanga in particular. The book is a great read and worthy of active debate. During this author’s interview and contacts with Krueler, the old Boer never alluded to anything being out of place or questionable about Meinertzhagen.

Tanga was a decisive German victory, although it “was an inconsequential engagement in the cosmic sense,” with the thousand German and colonial troops defeating and halting the advance of eight thousand already landed, with an additional two thousand men marching to join them. 377 Word came that although their losses were comparatively light (German casualties according to Lettow-Vorbeck were fifty-four Askaris and machine gunners killed) the dead included Captain von Prince, Krueler and Ley’s company commander.378 Dane places the numbers of German and their allied dead at “eighty-five killed including five officers, eighty wounded and one missing in action.379

Never to that date in the history of German arms had there been such a one-sided victory. The Germans and their allies spent the next week collecting and burying the dead. “It reminded me of Spion Kop all over again. How I really hated the fighting and killing. But what else was I going to do?”380

Hew Strachan’s opinions are worth noting: “The victory at Tanga made Lettow a hero. It gave him the authority to deal with Schnee, and it inclined Schnee to accept Lettow’s point of view. Moreover, the faith of the Schutztruppen, both in themselves and in their commander, was confirmed. But it also encouraged Lettow-Vorbeck in his pursuit of the decisive battle.”381

The next year proved interesting for Krueler; rumors had spread that his old commanders, working with the British, were operating in large numbers against the Germans in East Africa. In November 1914 British and South African troops led by Smuts had launched an attack against German bases east of Kilimanjaro, a position “held by Captain Georg Kraut and with three companies of Askari and a mounted company of Europeans.” This operation would repeat itself in March 1916.382

Also during November 1914 many other factors developed, shaping Africa as a future battlefield. The Allies sent a thousand troops against the Germans and their colonial troops, taking Salaita and forcing the Germans back west of Taveta and the hills of Reata and Latema, and as far as Longido without significant contact or casualties. The assault against Captain Georg Kraut at Latema on November 16 was initially unsuccessful, but the repeat of the Allied attack forced him to retreat by 1950 hours, and by 2130 Lettow-Vorbeck lost telephone contact with the German force. Kraut ordered a retreat at 2200 hours. 383 Ironically, Kraut and his men would fight over this same terrain a year and a half later in March 1916. At about the same time Lake Victoria became a battlefront, although the Germans and their indigenous forces were able to repel the attackers.

Krueler and Ley both survived the Battle at Tanga without a scratch, and they were soon to find themselves in a new role in a different, strange, and beautiful yet deadly part of Africa. Lettow-Vorbeck issued the order for his troops to board the train for New Moshi, or load into trucks for the four-day ride to move all men and materiel to establish a new headquarters.384 The least essential personnel would have to force march with their basic load of fifty-five pounds. Given the heat and mosquitoes, as well as the inherent diseases befalling some of them, this march would take between seven and ten days.

Krueler and Ley were part of the unfortunate group who “humped it” along the dusty roads, often choked by clouds of dust as trucks ran up and down the road, loading and later unloading soldiers. The good thing for the men was that those on the march were being selected en route as the days wore on. Lettow-Vorbeck knew that disease would weaken his army more than the British, so on his order “experts in hygiene traveled up and down the road, and did what was humanly possible for health of all of the carriers [marching soldiers], especially against dysentery and typhoid.”385

Many of the men had body lice, so there was the fear of typhus. A fumigation and delousing tent had been erected and all the soldiers, black and white alike, without regard for race, stripped their clothing, which was saturated in the chemical solution, and the men were sprayed and powdered. After a few hours, they were allowed to bathe in the river, with soldiers posted along the banks with rifles to protect the bathers from crocodiles. Once the men were finished and dressed in their own makeshift uniforms they were given medical check ups. Those cleared rejoined their units, with only a few not making the grade.386

The German HQ at New Moshi was set up with telegraph services that linked it with other German units throughout East Africa. Reports came in day and night on enemy and friendly troop movements. Due to his English-speaking skills, the rare intercepted telegraph or radio transmissions were handed to Krueler or one of the few English-proficient Germans.

The bulk of the intercepted information was essentially worthless. One of the German officers proposed an imaginative plan to send a small team into British territory, splice a wire into their telegraph lines, and run it back to a German field station. Krueler joined a three-man German team specializing in this type of work. They would depart HQ, locate the enemy’s main line, and establish a link and reception telegraph. The British telegraph transmission would all be transcribed, Krueler would translate, and the information would back by a messenger. It was never possible to run enough wire to link directly into the German HQ.

The intercept team headed north into Kenya following maps that showed the previously known enemy telegraph lines. “I think that they were really hoping that the British had not relocated these. I did not feel like walking around the wilderness in enemy territory, looking for wires stretched across poles. Who knew if they still existed?”387 After two weeks they failed to locate any of the lines thought to be erected in the areas concerned, so the team returned empty handed. The great adventure had proven to be an illusion.

The unit then moved to the Kilimanjaro region just northeast of Moshi, which was the largest town in the shadow of Africa’s Mountain Empress; this would be the new German base of operations. The lovely setting would also soon become a battleground. “The only thing that would spoil its beauty was the smell of death.”388

Pieter Arnoldus Krueler at age 12.—Pieter Krueler

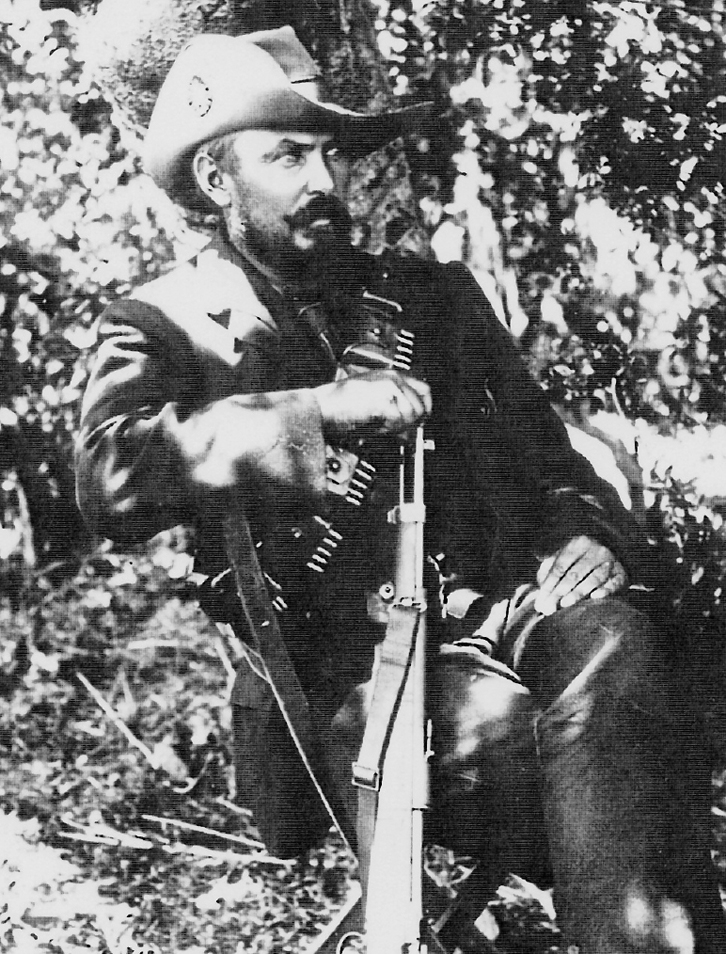

Pieter’s farther, Jan-Hans Ruyd Krueler in 1898. He was killed by British troops under mysterious circumstances, and his wife, youngest son, and daughter disappeared into the British detainment (concentration) camps. His oldest son, Paul, died at Paardeberg.—Pieter Krueler

Boer General Stephanus Paulus Kruger (circa 1901) was also state president of the Transvaal from December 30, 1880 until the end of the Second Boer War in 1901. He is shown here at his fourth inauguration in 1898.—Imperial War Museum

Anna, three-year-old Paul, and their father, Jan-Hans Ruyd Krueler.—Pieter Krueler

Boer father and son in the field, circa 1900.—Imperial War Museum

Twice a day, at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, battles of the Second Boer War were reenacted by four hundred Afrikaner war veterans and British soldiers against the backdrop of a village of Swazis, Zulus, and other African peoples. Pictured is a skirmish in the Battle of Colenso.—Library of Congress (wikimedia)

Twenty-six-year-old Winston Churchill photographed while on a lecture tour of the United States in 1900. Churchill, while a lieutenant, was working as a war correspondent, and was present at some of the conflict’s major battles, in particular Spion Kop. He and Krueler met in the 1950s in Kenya, and became friendly acquaintances. —Library of Congress

The battle for Spion Kop crest line was brutal and unyielding. —Africana Museum, Johannesburg

British dead after the battle at Spion Kop, January 24, 1900. This was the first major defeat for the British during the Second Boer War but proved to be a Pyhrric victory for the Boers.—Wikimedia

Commandant-General Louis Botha commanded Boer forces at Colenso and Spion Kop and thereafter until the end of the war.—Africana Museum, Johannesburg

The British main trench on the morning following the battle of Spion Kop. —Africana Museum, Johannesburg

A Boer commando at the foot of Spion Kop.—Africana Museum, Johannesburg

The people of Toronto crowded Yonge Street to celebrate the end of the Boer War. The British Army drew troops from around the Empire, including Canada and Australia, to defeat the Boers.—City of Toronto Archives

Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, military commander in German East Africa during the First World War. —Bundesarchiv (wikimedia)

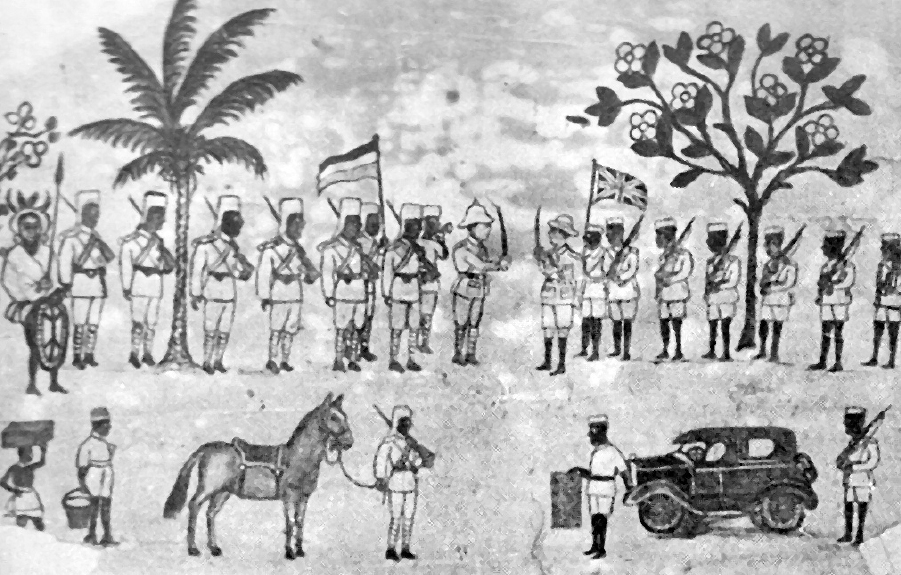

General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck surrendering his forces to the British at Abercon (present-day Mbala) in Northern Rhodesia.—National Museum of Tanzania (wikimedia)

British BL 5.4-inch howitzer and South African crew during the East Africa Campaign. —South African Defense Force Archive

Askari machine-gun crew in 1915.—Courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild 105-DOA0151; Photo: Dobbertin, Walther, ca 1906–1917

German East Africa Defense Force during World War I hauling one of the ten guns salvaged off the scuttled light cruiser Konigsberg.—Courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild 105-DOA3100; Photo: Dobbertin, Walther, ca 1916–1917

Pro-Republic Basque fighters in Elgeta, Gipuzkoa, Basque Country, during the Spanish Civil War, around 1936–1937—www.argazkiak.org/photo/elgetako-gudariak/ (wikimedia)

Field Marshall Jan Christiaan Smuts just after World War II. Smuts was a good friend of the Krueler family before the Boer War, and despite fighting on opposing sides during World War I, Smuts and Pieter Krueler remained friends.—Imperial War Museum

Jim “The Man” Schneeberger during part of the arduous selection process for the Selous Scouts in 1978. —Jim Schneeberger

Selous Scout cap badge worn on the berets of the commandos.—Author’s collection

Selous Scouts living in the United States at a June 2012 reunion: (left to right) Rich Howe, Ralph Hayes, Chris Gough, Mark Forshaw, Chris (Stretch) Ferreira, Clive Wood, Jim Schneeberger.—Author’s collection

Flight Lieutenant Ian Smith of the Royal Air Force, pictured circa 1942, during his service in the Second World War. Smith was later Prime Minister of Rhodesia between 1964 and 1979. —Wikimedia

Bishop Abel Muzorewa of Rhodesia arriving at Schiphol Airport, Netherlands on August 31, 1975. Muzorewa was prime minister of the short-lived Republic of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from June 1 to December 12, 1979.—Rob Bogaerts/Anefo (wikimedia)

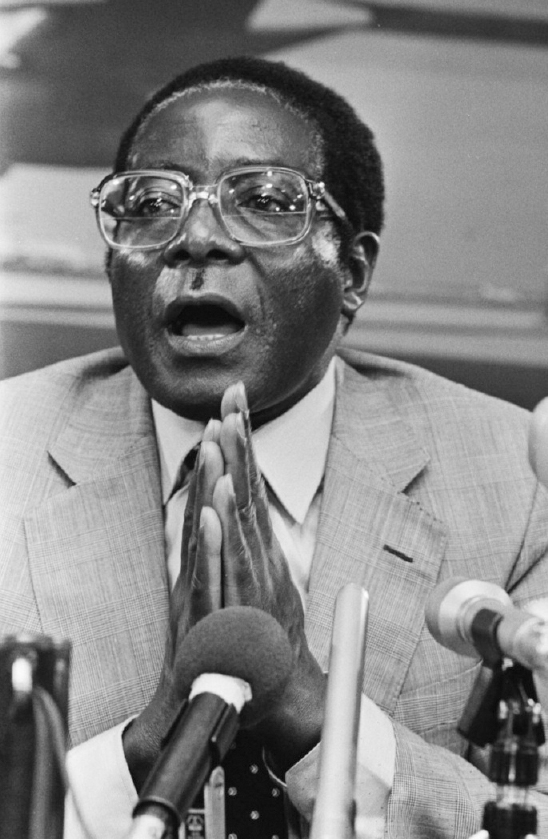

Then Prime Minister Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe at a June 4, 1982, press conference at Schiphol Airport after a three-day trip to the Netherlands. Mugabe is currently the president of Zimbabwe, an office he assumed at the end of 1987 following seven years as prime minister.—Marcel Antonisse/Anefo (wikimedia)