SHEN CONGWEN’S LIFE FELL into grave disorder amid imminent national crises in 1948. Labeled a reactionary indulging in “pornographic whims” earlier that year,1 he was ostracized by progressive colleagues and students at Peking University, where he taught, and became increasingly alienated from friends and even family members who aspired for the revolution. By early 1949, Shen was showing signs of a nervous breakdown. He suffered from paranoia and experienced hallucinatory episodes.2 On March 28, Shen tried to kill himself by slitting his throat and wrists and drinking kerosene; he survived only through luck.3 It was arranged for him to take a secluded rest in the following months. “He was ill for a long, long time.”4

On the night of May 30, 1949, Shen Congwen wrote an essay, “Wuyue sa xia xiashidian beiping sushe” 五月三十日下十點北平宿舍 (In a dorm, Peking, May 30, 10:00 p.m.):

Everything at home appears as tranquil as ever. I can hear the sounds of drumbeats from afar, horse crickets fluttering in the kitchen, my sons’ snoring, and the arias of Carmen, La Traviata, and Madame Butterfly from the radio. [My wife] Zhaohe is well and adorable, my kids are self-sufficient and independent, and I am still working at my desk.… [But] the world has changed; everything has lost its meaning. I have been thrown into a world of oblivion, isolated from all happiness. I don’t understand what makes me so sad while I am facing the world aimlessly.5

Shen notes a photo he took with Ding Ling 丁玲 (1904–1986) and Ling Shuhua 淩叔華(1900–1990) nineteen years before, when he was escorting Ding Ling and her newborn baby to her hometown after her husband Hu Yepin’s 胡也頻 (1903–1931) execution by the Nationalist government.6 Then he writes, “the night is bizarrely quite. The Dragon Boat festival is coming soon.… Cuicui, Cuicui, are you asleep in Room 104, or thinking of me amid the cuckoos’ songs in commemoration of my death?”7 Shen Congwen and Ding Ling had once been close friends, but they had parted ways for political reasons. Cuicui, the heroine of Shen’s best known novella, Border Town, embodies Shen’s vision of ideal beauty par excellence. When faded memories and fictional fantasies, phantom images and hallucinatory sounds all escalate, Shen verges on a total meltdown: “I am searching for the I which is lost!”8

Shen Congwen’s essay renders a poignant portrait of his mental state at a critical moment in modern China. It captivates because it exemplifies Shen’s lyrical sensibility at its most intricate: his capacity to invoke associations between familiar objects and poetic pathos; his “anticipatory nostalgia” about the inevitable decomposition of things he cherishes; his death wish, which comes across as a tender desire. Above all, the essay registers Shen’s acute sense of time. May 30, 1949, at 10:00 p.m. suggests either a suspenseful pause in the shadow of cataclysm or a mysterious signal leading toward an unknown apocalypse.

Shen was denied participation in the First Meeting of the National Writers’ Association, which took place in early July 1949.9 Although he tried to resume his career after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, he found it difficult to accommodate the ethos and demands of the new regime. He was assigned to work at the National Museum of History in 1950, and his literary reputation gradually fell into eclipse in the following years.

Shen’s confrontation with the Communist Revolution is emblematic of the fate of many a contemporary writer who failed to keep up with the times. But putting his case into a broader context reveals a more complex picture. Shen was the most popular nativist writer and lyrical stylist in the thirties and forties.10 Although labeled a Beijing School modernist and a liberal,11 he was always a loner with an agenda of his own. Even long before 1949, Shen had already felt discontented with the lyrical discourse for which he was famous. He sought a breakthrough during the war, to no avail, and the mounting postwar chaos further intensified his predicament. Meanwhile, he was allegedly having an affair with his sister-in-law, which almost ruined his marriage.12 In a way, the Communist Revolution was simply the last straw. Shen’s crisis originated in his inability to reckon with his own literary pursuit and his existential dilemma.

The concern of this chapter is Shen Congwen’s search for a creative vision throughout national and personal crises, what he later described as “abstract lyricism.”13 For Shen, wars, ideologies, and fixations on immediate reality had driven many Chinese people to the extremity of either stupor or fanaticism, a spiritual crisis that in the long run would damage Chinese civilization more than any physical atrocities. To rescue China from her crisis, Shen believed it was urgently necessary to configure “abstract values.”14 He regarded poetry as the medium that best manifested his “abstractionism.” By poetry he meant more than the exquisite form of linguistic constructions. Beyond textual representation, Shen contends, poetry manifests itself through a variety of visual and acoustic patterns of life; he claims that “all arts should enable their creators to evoke an element of lyricism.”15 At its best, poetry crystallizes the sensuous and the spiritual into something close to a celestial revelation, so that it testifies to “the divinity that permeates our life.”16

The utopian inclination in Shen Congwen’s pursuit is easy to see. The increased frequency of the term chouxiang 抽象, or abstract, in his writings from this time particularly seems to indicate Shen’s indulgence in an aloof, even transcendental state of mind, a far cry from the current revolutionary mode of thinking. But before concluding that Shen was withdrawing into his own ivory tower, one has to look into at least two factors underlying his lyrical abstractionism.

First, as argued in the introduction, Shen Congwen was always keen on the historical motivation and regional heritage of his writing. That is, he wrote so as to bear witness to the “traumatism”—a primordial complex of truncation and pathos—rooted in the culture of Chu. The symptoms of traumatism are traceable as far back as the suicide of Qu Yuan, the arch-poet of lyricism of the south. For Shen Congwen, while the “abstract values” represent the ideal projections of humanity, they are also intertwined with historical contingencies. Beneath Shen’s pursuit of “the divinity [of abstract values] that permeates our life,” therefore, there always lurks a melancholy prescience that no sooner than the “divine” reveals itself, it will dissipate in the flux of human and inhuman interferences. “Abstract values,” accordingly, are no more than “absent causes” whose valances lie in their tantalizing appeal and inevitable self-negation.

Second, while yearning for “abstract values,” Shen Congwen was doggedly seeking a vehicle that could best mediate between the abstract and the realistic. After years of practice, he no longer considered literature the only viable form to facilitate his pursuit; he wanted to discover the lyrical articulations in other forms, such as music and even mathematics. Moreover, Shen showed an increasing interest in material culture—not only paintings, calligraphy, and other forms of illustrative arts but also genres less associated with elite taste, such as bronze vessels, woodblock prints, stone carvings, lacquer handicrafts, and porcelain ware. He even trained himself to become an amateur collector of Ming and Qing porcelain plates and dining ware, embroidered works, lacquer containers, colored paper, and the cloth jackets of Buddhist texts.17 As a result, Shen developed a sensibility that informed both his aesthetic taste and his archaeological knowledge. As he later described, simply through sensorial contact with an art object—feeling its quality, looking at its design, and examining its material composition—he could tell the “story” about the time when it came into existence and, more suggestively, the “abstract values” it embodied.

Thanks to my experience acquired as a result of patience and love I was able to recognize from the shapes and patterns the character and aesthetic features of assorted artworks—just like the experience a middle-aged person could have learned from human affairs. As time passed, I could caress either the edges or the bottoms of Ming and Qing porcelain plates and bowls with my fingers and almost tell the relative time when they were produced.18

Feeling and materiality, subsidiary awareness and positivist verification complement each other in anticipation of his self-styled archaeology.

Nevertheless, Shen Congwen had yet to fully grapple with the implications of his search during this period. He oscillated between the formal contemplation of textual and illustrative arts and a sense of defeatism toward history, and between the connoisseurship of the art objects of everyday life and the fantasy of political utopia. These interests do not combine to project a coherent vision of lyricism; instead, they conflict and generate a vicious tension. When that tension was compounded by the political situation, it pointed literally to the dead end of Shen’s search.

What makes Shen Congwen’s adventure really compelling is the fact that, for all the adversities he endured after 1949, he continued to ponder the possibility of a lyrical vision. In chapter 1 I have discussed Shen’s invocation in 1952 of a “history with feeling,” as opposed to the history of actions underwritten by the Party. This marked the beginning of his renegotiation with his time and himself. As years went by, Shen came to realize more and more that “abstract lyricism” need not be sought after merely in genres such as poetry or music; it could be called forth amid the multitude of art objects he encountered in the museum daily. In place of literature, he found in his position as an art historian a new vocation that enabled him to bring his lyrical vision, his historical traumatism, and his fascination with material culture together. The result is a unique methodology of “lyrical archaeology,” best represented by Shen’s stupendous work Zhongguo gudai fushi yanjiu 中國古代服飾研究 (A study of ancient Chinese costume, 1981).

This chapter traces the tortuous path Shen Congwen took in search of his abstract lyricism from the 1940s to the 1960s, a search that culminated in his discovery of lyrical archaeology. By describing Shen’s transformation from a writer to an art historian, I ask how he came to terms with his literary career, which ended abruptly after 1949, and how he reconciled his lyrical vision with the mandate of socialist materialism. Particularly, I look into the motivations that compelled him to dedicate the last forty years of his life to the study of Chinese handcraftsmanship and costume history. Through examining and annotating—and feeling—hundreds and thousands of classical Chinese art objects, fabrics and garments in particular, Shen managed to weave his discoveries of abstraction and materiality, fabrication and history, into a unique narrative.

The chapter is divided into two parts. The first part describes three moments that were crucial to Shen Congwen’s changing attitude toward his life and work. I call these “epiphanies” because each was occasioned by a chance encounter with a scene or object, and each led Shen to a sudden but deep understanding of his existence vis-à-vis the historical condition. The second part introduces Shen’s writing of A Study of Ancient Chinese Costume and its significance with respect to his re-vision of his lyrical agenda.

Three Epiphanies

In February 1947, Shen Congwen received a poetry volume from a young poet friend.19 Instead of the poems, Shen was attracted to a series of woodcut illustrations in the book, which showed “a mixture of childlike innocence and passionate boldness.” He found in the illustrations “not only the artist’s wisdom and passion but also a lyricism that combines these two elements. Without a deep and subtle understanding of poetry, the artist could not have reached such a concise manifestation.”20 Shen became curious about the woodcut artist’s identity, only to find out that he was none other than Huang Yongyu 黃永玉 (b. 1924), son of Shen Congwen’s cousin Huang Yushu 黃玉書. Shen Congwen was so struck by this happy coincidence that he wrote an essay, “Yige chuanqi de benshi” 一個傳奇的本事 (The true story of a legend, 1947).

Although he would later become a household name in Chinese arts, in the forties Huang Yongyu was a struggling young artist. In a way uncannily reminiscent of his uncle’s decision in his adolescent years, Huang left home to pursue his dream at twelve, and he led a life full of rough-and-tumble adventures before arriving in Shanghai, where he joined the Woodcut Movement or muke yundong 木刻運動.21 By the time his essay was published in the fall of 1947, Shen Congwen had met Huang Yongyu only once, briefly in 1934.22 But from mutual correspondence, Shen had learned about the young artist’s harsh life and the misfortune of his parents. Their stories provide Shen a vantage point from which to look back at the vicissitudes of his hometown region, West Hunan, over the previous two centuries.

Huang Yongyu’s woodcuts thus served as a catalyst, igniting Shen Congwen’s thought on an array of issues, from the history of his hometown region to its artistic representation in modern times. As Shen notes, Huang Yongyu’s artworks, marvelous as they are, only make him feel “a deep pathos” because they come as illustrative testimonials to the “contingencies of fate.”23 Few of the natives are as lucky as Huang, able to develop his talent against all odds. Huang’s parents, Shen recalls, were both committed artists and art educators, yet, as with most of their peers, their talents were wasted as a result of both bad luck and societal chaos. Shen raises a sober question: If it was deplorable that Huang’s parents were unable to fulfill their dreams, wouldn’t it be more deplorable that hundreds and thousands of young natives of West Hunan lost their lives, even before being able to entertain any dreams, in the numerous atrocities from the late Qing to the Republican era?

When writing about Huang Yongyu, Shen also kept an eye on the Woodcut Movement, which since the thirties had been a sanctioned campaign among the revolutionary artists and writers.24 Lu Xun, in particular, played a key role, introducing to its members Western examples and theoretical models.25 In contrast to other forms of modern art, woodcuts were said to better reflect both the contested circumstances of Chinese reality and the “primitive passions” inherent in the leftist imaginary.26 Shen welcomed this popular art form, but he had a different take on its conceptual framework and outcome. As early as 1939, he already commented that for all their avowed purposes, revolutionary woodcuts served at best as visual supplements to topical events and political propaganda; they were “too closely related to what was happening.”27 He urges artists to refine the form of their works. Granting the need to convey political urgency and antitraditionalist sentiment, Shen concludes, modern woodcut artists should nevertheless draw inspiration from sources such as the stone carvings discovered in the Wuliang Shrine, Chinese New Year woodblock prints, and the ethnic artworks of southwestern China.28

When Huang Yongu arrived in Shanghai in the late thirties, the Woodcut Movement had already formed its conventions in theory and practice. Huang was willing to endorse these, but political commitment aside, he distinguished his own works with rich ethnic motifs, a decorative style, and a “simple and affective” charm. In the words of Li Hua, a leader of the movement, Huang’s works create “an ambiance of joy, innocence, and poetry.”29

Shen had made a similar observation about Huang’s works, but from a different perspective. For Shen, the young artist was “full of energy and very mindful of design, thereby demonstrating both the congenial, unbridled nature of his parents and the rugged and subtle experience of his own life. The two styles do not contradict but complement each other, in such a way as to give rise to a gracious sense of humor.”30 Huang’s works, accordingly, helped Shen materialize the principle of lyricism for which he yearned.

Thanks to Huang Yongyu’s art, Shen was able to resume his dialogue with the Woodcut Movement members. While both parties concurred about woodcuts’ unique capacity to bear witness to reality, how that “reality” was to be represented, or literally, inscribed, remained debatable. Where the majority of the woodcut artists were eager to depict social abuses and revolutionary sentiment in a raw, striking manner, Shen Congwen called for stylization and lyricality: beneath surface political representation, artists should capture the emotional turbulence of a time in such a way as to induce multiple responses. There may be an analogy between the woodcut and Shen’s “lyrical archaeology”: just as a woodcut brings about its visual effects by chiseling a block into refined layers of dimensionality, history is explained when its dark niches can be carved out in full depth.

As Shen Congwen sees it, Huang Yongyu’s works need not merely serve to critique reality or project a dreamland—a history as it is or should be. Rather, the way Huang crafts his motifs and lines, colors, and cuts amounts to an evocative deed, leading him and his audience into the sunken passage of memories. Be it a ritual dance in the Miao tribal region or a chase after strayed geese in a village, an old woman toy vender dozing off, or a grandpa and his granddaughter playing flutes under the sun, Huang’s works are indices that arouse not only nostalgia but also anticipatory nostalgia. The lyricism Huang (and Shen) seeks is not a mere recollection of the past, but a lyricism that gives forth a disjunctive and uncanny aura, unleashing the imagination and generating urgency about observing the present and making the future that “will have been” remembered. In other words, the traces of Huang’s pastoral illustrations are powerful not only because they are historical evidence of sorts, but more importantly, because they inspire the audience to think of the futurity embedded in the past: missed premonitions, unheeded prophecies, and lost opportunities, whose meanings could not be grasped until the present time—all too late.31

A woodcut illustration by Huang Yongyu for the 1948 edition of Shen Congwen’s Border Town

Huang Yongyu’s works triggered Shen Congwen’s thoughts about the fate of Huang Yushu, Yongyu’s father and Shen’s cousin. Huang Yushu was an aspiring artist when Shen ran into him in Changde in 1921. Shen recalls how, penniless, they were stranded in an inn and “goofed around” together, and how he wrote more than thirty love letters in Huang’s name to help the latter pursue a young art-education girl student. Three years later, Huang married the girl. The romance did not end happily, however. The artist couple was never able to realize their dreams; meanwhile, family obligations and social turmoil had drained every bit of their energy. When the cousins were reunited in 1937, Huang Yushu was already a despondent army clerk, a father of six, and a sick man. He died six years later.32

In Huang Yongyu’s illustrations, Shen thus discerns not only a tragic family story but also an allegory about the betrayal of one generation of Chinese youth inspired by the May Fourth Movement. However, Shen’s exegesis does not stop here. He expands the scope of his reminiscences to the men and women of his hometown region involved in the riots and wars in recent centuries. West Hunan, Shen holds, had been an area known for chivalric gallantry and regionalist loyalty, a local manifestation of romantic valor and idealism. In modern times, these virtues had driven numerous young men to become soldiers, thereby giving rise to the legend of the unbeatable “Gan Army.”33 Nevertheless, for either military or political reasons, the Gan Army had been continuously assigned by the Nationalist regime to the most dangerous front lines without adequate support, and as a result the Gan soldiers were killed by the thousands. As the war went into the sixth year, “almost all the males of West Hunan aged between sixteen and forty had already lost their lives in various battles.”34 The final collapse of the Gan Army, as Shen describes it, happened only “in a most ambiguous situation.”35 The army was sent to defend Eastern Shandong Province against the Communist forces in early 1947, only to be completely wiped out in less than a week.

How did a troop that had once been known for its insurmountable strength and will power come to such an abrupt and total fiasco? From various sources Shen infers that the rout had little to do with either mistaken strategy or insufficient arms. Rather, it simply “resulted from the soldiers’ deep-seated resentment of the massive abuses and atrocities among Chinese themselves. [The Gan Army] fell apart because of both its antipathy toward the civil war and its despair about reality. Under such circumstances, all my friends and relatives from West Hunan, together with their ideals, perished in but a few days.”36

At his gloomiest, Shen Congwen contemplates a mysterious, suicidal impulse that drove the Gan Army to meet its fatal destiny. Deprived of any hope for the future, the soldiers could take only one action to protest the status quo: self-destruction. For Shen, along with the army, something quintessential about West Hunan—its ethnic pride, romantic vitality, and will to fantasy—is gone forever. And because of his bond with the army, Shen could not but feel that what had happened to his Gan brothers would soon happen to himself, and eventually to all Chinese of his generation. In an almost prophetic tone, he writes,

Given the circumstances of the present, or even the next half century, any effort at social reform of humanity will prove futile. Despite myriad individual struggles for self-betterment, a tragic force of fate will hurl the Chinese people’s search for solidarity into entropy, or any disguised form of suicide.37

Still, Shen Congwen ends on a positive note. He suggests that despite the dire circumstances of West Hunan in particular and China in general, one should still try to rescue select abstract values from extant cultural and artistic constructs. “A new beginning cannot be begotten until after a total destruction has taken place.”38 This hope for a new beginning, Shen claims, could be found in a younger generation of artists like Huang Yongyu.

But Shen’s tone is nothing if not equivocal. In relating the stories of Huang Yongyu, the Gan Army, and West Hunan in the modern century, he shows ample pessimism. He is keenly aware that the line between artistic creativity and historical contingency is thin and that any human effort to withstand fate may be futile. This pessimism, as previously argued, is symptomatic of Shen’s traumatism, traceable to the originary setback of Chu culture. Looking ahead, he finds himself again pushed to the edge of a historical abyss—only this time, he sees no way to turn back. Can Huang Yongyu’s artworks truly redeem someone like Shen from his sense of doom? Can abstract lyricism really promise a leap over the historical abyss? The pastoral serenity of Huang’s illustrations seems to refract a phantasmal shadow of a dream that never was and never will be realized. Little wonder that Shen Congwen should feel “deep pathos” upon seeing those woodcuts, however innocent and vibrant they appear on the surface. In his call for abstract lyricism, despair looms. Instead of a eulogy for the life force of Huang Yongyu’s art, “The True Story of a Legend” comes across more like Shen Congwen’s self-elegy.

SHEN’S SENSE OF DOOM became an obsession in late 1948 when he came under mounting attacks from leftists. In early 1949, he “fell seriously ill” and was taken to Tsing-hua University for a rest. His despair was manifested in his letters to his wife, Zhang Zhaohe, as well as his notes on previous works. “I should take a rest now. My nerves have reached the point where I cannot bear any more. Even if I won’t die, I will go crazy.”39 “The light has gone out, while a gusty wind is blowing. So there is a whirlwind within me. Thus all is to be put to an end.”40 “Let me take a break, a painless break, and never wake up. That will be fine. Nobody understands what I am talking about and nobody dares to say that I am actually not crazy.”41 “I have to be sacrificed–this is my destiny … one should give up hope on a sinking boat, and pass on one’s love to the younger generation.”42 “I have been trapped in a quagmire.… Far and away from the light on the other shore, the boat is sinking slowly … the boat is going down.”43 For a writer who had always invoked a river and boat as the major trope of his literary landscape, these jottings about a sinking boat foreshadowed the moment of meltdown. Then, on March 28, 1949, Shen Congwen tried to take his own life.

Multiple reasons have been cited for Shen Congwen’s suicide attempt. Ever since the early forties, as a result of frustration with writing, he had

considered suicide. Recent scholarship indicates that Shen’s death wish coincided with his aborted extramarital affair with his sister-in-law, Zhang Chonghe 張充和.44 Moreover, Shen is said to have suffered from paranoia about Communist persecution.45 But there may be other factors that make his attempt so compelling to us. Qian Liqun 錢理群 points out that his is not a singular case in modern times. Along with Wang Guowei 王國維 (1873–1927) and Qiao Dazhuang 喬大壯 (1892–1948), Shen opted for the extreme measure to guard his cultural integrity at a moment of historical crisis.46

One might reprove Shen Congwen for lagging behind the spirit of his time, which affirmed the life force and the discipline of self-renewal. But insofar as his “anachronism” indicates a (deliberate) blurring of different temporalities as well as paradigms, Shen seems arguably more modern than most of the self-proclaimed modern literati of his time. For on the eve of the Chinese Communist victory, he had already discerned that “history” is something more than the streamlined realization of enlightenment and revolution. Faced with radical incompatibilities between the public and private projects of modernity, Shen tried to assert his own freedoms negatively, in the willful act of self-annihilation.

Shen Congwen published an essay, “Sugeladi tan beiping suoxu” 蘇格拉底談北平所需 (Socrates on the needs of Peking), in early 1948. In it he visualizes Peking as the garden city “that history meant it to be,” a place covered with flowers and ruled by architects, theater workers, and musicians. Instead of propaganda, the radio broadcasts Beethoven; instead of ideology, policemen enforce garden work and family hygiene. Shen even fantasizes about founding an art academy in the garden city. Headed by a philosopher cum poet, the academy teaches both Chinese and foreign literature, philosophy, archaeology, folklore, and music.47 Given the sentiment of China in 1948, the essay was no doubt denigrated as a whim of an irresponsible liberal. In fact, however, Shen was quite sober about the prospects for Peking—and himself—regardless of his utopian narrative. If Socrates was driven to suicide for his idealism, what would be Shen’s fate in making a Socrates-like proposal?

Thus, the “stage” was set for Shen Congwen’s attempted suicide. Intriguingly, the fatal action may have been caused by a domestic episode far from anyone’s expectation. On March 26, 1949, Shen came upon a photo his wife had had taken on the same date twenty years before and was completely overcome by it. Miraculously, the photo has survived all hazards since 1949 and is still available for a belated inquiry.

Dated March 26, 1929, it shows a young Zhaohe, then a sophomore at Chinese University in Shanghai, posing with eight other basketball teammates and two male coaches. Shen Congwen wrote two captions on the back of the picture:

Zhaohe at school in Wusong, holding a basketball. Congwen, Peking, 1949

Viewing this picture on March 26, 1949, as if there were cuckoos sounding next to my ear.48

So far as we know, these are the last words written by Shen before his attempted suicide.

What did Shen Congwen “see” that triggered his death wish? In the photo, Zhang Zhaohe is in the center, holding a basketball, clearly the focus of the team. Behind the team is the entrance of a Western-style building, with its four doors closed. Together with her teammates and coaches, Zhang stares at the camera eye in a poised, distanced manner. Her posture indicates that she is a player of a modern sport Shen could not have been good at, and that she is surrounded—no, guarded—by a group of strong and vigilant supporters, as if ready for another round of competition. The most conspicuous object is the basketball Zhang holds in her hands, on which appears the number 1929.

In 1929, Shen was a young professor at Chinese University madly in love with his student Zhang Zhaohe, who had little interest in her professor. The backgrounds of the two could not be further apart; Zhang was a vivacious, athletic girl from an elite family in Suzhou, whereas Shen, who always called himself a “country man,” by Zhang’s age had experienced things the latter could not have imagined. This “country man,” however, found Zhang to be his Muse at first sight, and he was determined to marry her. The year 1929 saw Shen writing numerous love letters and some of his finest romantic stories in Zhang’s honor. To capture his beloved’s heart, he would make even more desperate gestures, including suicide threats. Zhang eventually succumbed to Shen’s pursuit; they were married in 1933.

Zhang Zhaohe’s photo taken on March 26, 1929, and Shen inscription on March 26, 1949. Courtesy of Mr. Shen Longzhu

We do not know when the photo in question was made available to Shen Congwen, but we do know how he felt twenty years after it was taken, thanks to the comments he put down on the back. For Shen, the Zhang Zhaohe of 1929 was still an inaccessible object of desire, a figure of beauty that pained and inspired him alternately. This girl had little in common with him, but her vivacious profile and dark complexion would become the prototype of a long gallery of his heroines: Sansan, Xiaoxiao, Yaoyao, and above all, Cuicui of Border Town. By 1949, however, Shen Congwen’s career had come to a dead end and his relationship with Zhang Zhaohe had been through several ups and downs. Zhang was deeply hurt when Shen was alleged to be having an affair with her own sister; and she could not understand her husband’s fixation on abstract thoughts of beauty amid national crisis. Indeed, as Shen Congwen was suffering from paranoia, Zhang and their children were curious about the revolution and eagerly awaiting its arrival.

The front side of the photo thus illuminates and undercuts the historical and affective significance of the back side, and vice versa. While Zhang Zhaohe dominates the surface, Shen Congwen literally leaves his imprint on the back; while Zhang celebrates with others the year 1929 in photographic immediacy, Shen comments on the back about the passage of time and the ephemerality of human relationships. The number 1929 that appears on the basketball Zhang holds in the picture may very well serve as a Barthesian “punctum,”49 an unintended index to the poignant implication of the picture—about a time when Shen Congwen had just “moved into the complex metropolis, which was bound to ruin him as a result of a morbid development.”50 For Shen in 1949, the photo reenacts a phantasmal mis-en-scène, as if he were an accidental intruder into the historical site of 1929, peeping from behind the camera at a girl named Zhang Zhaohe posing for pictorial permanence. It is an innocent time, and a heuristic time, when the romance between the two was yet to take place. Only twenty years later would Shen come to realize that this moment of beginning, for everything from love to poetry, also marked the moment of incipient degeneration. By looking at a young Zhang Zhaohe looking at a camera eye in the distant past, Shen “saw,” as it were, himself in crisis. He was reminded of the fact that he was out of the “picture” in 1929 as much as he was in 1949.

Moreover, the photo is produced in the form of a postcard, an expedient option for epistolary correspondence. For some reason this photo-postcard was never sent to anyone; on the back side the address is left blank and there is no trace of either stamp or postmark. When he twice jotted down words on the postcard side of the photo in the spring of 1949, Shen behaved as if he wanted to communicate with someone. The two captions quoted above nevertheless sound more like his ramblings to himself. After all, even if he meant to write to the Zhaohe whose image appears on the reverse of the card, the intended communication seems to have lagged twenty years behind in both temporal and ideological terms. Jacques Derrida has used the postcard to illustrate the highly indecisive nature of textuality: both intimate and open, both referential and self-referential.51 The unsent photo cum postcard that engaged Shen Congwen, accordingly, points to a short circuit in time and memory as well as the dissipation of any meaningful communication.

Shen’s captions on the back of the photo-postcard bring something else into play. In contrast with the silence permeating the photo’s front side, a sound effect is invoked by Shen’s writing on its reverse: he seems to have heard cuckoos singing around him. Shen is of course familiar with the classical allusions of the cuckoo to unrequited love and romantic death,52 but in this case, he must also have had in mind the bird’s regional symbolism. In his letters to Zhang Zhaohe in 1938, when he was en route to the hinterland by way of his hometown region, Shen marked his itinerary in terms of the proximity of the birds’ singing. As he was approaching Yuanling, he heard

cuckoos singing everywhere, in such haste and sorrow. Clear but sorrowful.… Judging by their loud sound, the birds must be far apart from each other and few in number.… They look unimpressive in both shape and color.… They fly in haste and disorder as if they were fugitives; their postures are most ungracious, only that they sound so clear, far-reaching, sad, and bitter.53

It is no coincidence that just a few days before his attempted suicide, Shen described his situation as “chaotic and out of order, like a rainbow ruined by a new shower, leaving only an illusory reflection on the dew atop lotus leaves. After the rain, frogs can be heard everywhere; cuckoos are singing sorrowful songs for Cuicui.”54

Zhang Zhaohe’s photo thus instantiates a locus of seduction and trauma. Seduction, because the visual images remind Shen of a moment of passion at its most tantalizing; trauma, because the photo is always already a congealed moment of life, a snapshot, a signal of posterity. Trapped in Peking in the spring of 1949, Shen had no romantic figure to turn to for consolation anymore, let alone a “hometown” to go back to. Instead of cathartic relief, his scopic re-encounter with the 1929 photo brought about a death wish. In the midst of hallucinatory singing of cuckoos and spectral reflections of Cuicui, the young Zhang Zhaohe’s image in the photo amounts to an invitation to the other world, projecting the seductive and fatal power of Eros as Thanatos.

DURING THE FIFTIES, as Shen Congwen settled into his position at the National Museum of History, he gradually lost contact with the literary world. He still entertained the dream of staging a comeback, but he was learning to make peace with his time.55 His best writings from this period are mostly in the form of family letters. These are intimate in tone and most touching in how they reveal a former writer’s changing attitude toward his nation, family, and career. One dated May 2, 1957 is the focus of our discussion.

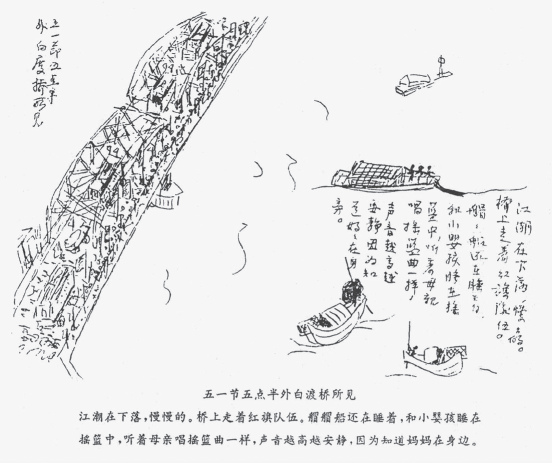

Shen took three trips to southern China during 1956 and 1957. Following an old habit, he diligently wrote Zhang Zhaohe letters reporting what he saw and thought about while on the road. From time to time he drew on the margins of the letters things he found interesting, such as a trash basket cum spittoon in Suzhou, a playhouse in Shandong, and an overview of the scenery of his hometown area. In the letter of May 2, 1957, which was sent from Shanghai, Shen drew three illustrations, showing three views of Waibaidu Bridge over the Suzhou River. They were based on what he saw from the window of his hotel room, which overlooked the river and the bridge.

The first illustration shows the bridge crowded with people on the upper left side of the frame, and four boats of different sizes on the right side. The caption reads, “Things seen around Waibaidu Bridge on May 1, Labor Day, 5:30 p.m.”56 It is supplemented by more descriptive words:

The tide was ebbing, slowly. A big political rally hoisting red banners was moving on the bridge. A small “maomao” boat was asleep [on the river], however, just like a baby falling asleep in the cradle to the tune of its mother’s lullaby. The louder the crowd sounded on the bridge, the quieter the baby felt, because he knew Mother was next to him.57

五一節五點半外白渡橋所見。江潮在下落,慢慢的。橋上走著红旗隊伍。艒艒船 (就是一種小船) 還在睡著,和小婴孩睡在摇籃中,聼著母親唱摇籃曲一樣,聲音越高越安静。

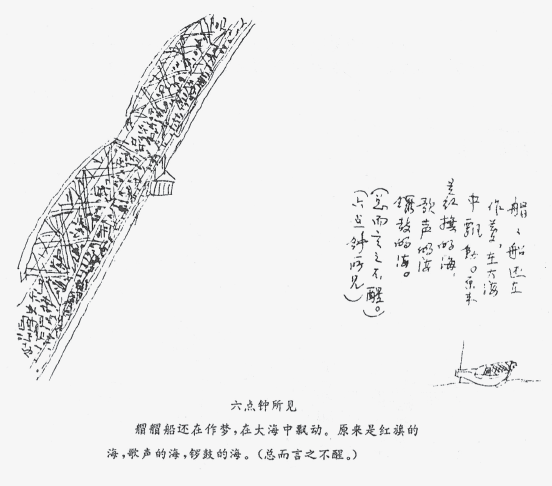

In the second illustration, the bridge is seen still crowded with participants in and spectators of the rally, but only one boat appears on the river. The caption reads: “Things seen at 6:00 p.m.”:

The small “maomao” boat was still in a dream, drifting in the sea. The sea turned out to be a sea of red banners, a sea of songs, a sea of drums and gongs. (Still, the boat just wouldn’t wake up.)58

艒艒船還在做夢,在大海中飄動。原來是红旗的海,歌聲的海,鑼鼓的海。 (總而言之不醒) 。六點鐘所見。

In the third illustration, the bridge, together with the crowd on it, disappears in a smokelike formation. Instead, a small figure with a fishing net appears at one end of the lonely “maomao” boat. Gone also is any reference to a specific time. Shen writes,

The noise was too loud; the person on the [maomao] boat woke up after all. He was fishing with a net the size of a straw hat, which could catch nothing but little shrimp. Strangely enough, he was still fishing.59

聲音太熱閙,船上人居然醒了。一個人拿着個網兜撈鱼蝦。網兜不過如草帽大小,除了蝦子誰也不會入網. 奇怪的是他依怪撈著。

Shen had developed a habit of “annotating” his family letters with illustrations as early as the thirties. In Xiangxing shujian 湘行書簡 (Letters on a trip to West Hunan, 1934), for instance, he makes clear from the outset that, instead of books, he carried a set of colored crayons so as to draw the scenery. The result is a series of fine illustrations, mostly of the mountains and rivers of West Hunan, which attest to his talent as a painter.60

The sketches are drawn mostly on the margins of his letters to Zhang Zhaohe; Shen meant to share with her his travel experience in pictorial terms, a special “language” between husband and wife. The 1957 illustrations reprise this intimate habit of communication, but there is something different. Whereas his illustrations from earlier years present vignettes of scenery in a random, casual manner, those from 1957 appear as a sequence of three frames underlined by a timeline of developing movements and textual annotations. Shen seems to tell his wife—and implied readers—a story, about how a small, personified boat survives all the noisy activities on a bridge during the daytime, finally gaining tranquility when everything evaporates into smoke at nightfall.

Illustration I, May 1, 1957, 5:30 p.m. Courtesy of Mr. Shen Longzhu

Illustration II, May 1, 1957, 6:00 p.m. Courtesy of Mr. Shen Longzhu

Illustration III, May 1, 1957, late night. Courtesy of Mr. Shen Longzhu

An illustration from Notes on a Trip to West Hunan. Courtesy of Mr. Shen Longzhu

Shen indicates in his letter that the illustrations are inspired by what he saw the day before, but they invite an allegorical reading.61 The significant date of International Labor Day, the rallying crowds on the bridge, and the sounds of slogan-shouting and singing are noted in a neat contrast with the temporal cycle of day and night, the lonely “maomao” boat on the river, a baby sleeping inside the boat, and a fisherman working at night. One may even infer some political innuendo in light of the historical context. May 1, 1957, does not merely mark International Labor Day, a most important date in the socialist calendar; it also coincides with a crucial turning point of Chinese Communist politics, the “Hundred Flowers Campaign” (Baihua yundong 百花運動).62 Mao Zedong had laid out the guidelines for the campaign one year before, on May 2, 1956. He openly supported the campaign in a published speech on February 27, 1957, in which he encouraged the people to vent their criticisms as long as they were constructive to the nation. This quickly drew thousands of intellectuals and literati to express their discontent with the party line in the subsequent weeks. The liberal sentiment unleashed by the campaign quickly caught Mao and his cohort’s attention. Mao indicated his reservations about the campaign on April 30, 1957. On the next day, May 1, an editorial appeared in Renmin ribao 人民日報 (People’s daily) titled “Zhongyang guanyu zhengfeng yundong de zhishi” 中央關於整風運動的指示 (Suggestions from the central administration regarding the rectification campaign).63 With historical hindsight, we know that this marked the initial move of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which resulted in the purge of hundreds and thousands of intellectuals and cultural workers.

We have no evidence as to whether Shen Congwen read the People’s Daily editorial on May 1, 1957. We can surmise, however, that years of experience in alienation had made Shen a cautious spectator of the ebbs and flows of political tides. The fact that he saw—looking down from his hotel room—the festive Labor Day rally in the daytime and the lonely “maomao” boat left on the Huangpu River at night must have struck a chord in his heart, compelling him to express himself with regard to the politics of the time.

Both the first and second of Shen’s illustrations show a bifurcated focus: the bridge on the left side and the boat(s) on the right. The viewer’s vision is expected to pan back and forth, or up and down, between the two sides, only reconciling them when moving toward Shen’s captions. It is in the third illustration, in which the bridge and the crowd on the bridge are erased, that the focus finds its anchor in the small “maomao” boat. There is also a shift of perspective among the illustrations. Judging by the position of the bridge in the first two, one can tell that Shen takes an aerial viewpoint from which to depict the activities on the bridge and the river. But the boats on the river are presented in disproportion to the bridge in size, as if Shen were seeing them at a much closer distance. Moreover, in the third illustration, where the bridge, the crowd, and even the river disappear in a smokelike formation, Shen seems to have lowered his gaze almost to a horizontal level in depicting the lonely fisherman’s boat. Also, having deleted all other visual objects in the third illustration, Shen effects a diffusion of perspectives, reminiscent of the visual tactic of “leaving spaces blank” often associated with traditional Chinese painting.

I take the shift of focus and perspective in these three illustrations as a clue to Shen Congwen’s subtle dialogue with history. For instance, the bridge in the first two illustrations is presented as open at both ends to the void beyond the frame. Because it is drawn in a slanting, vertical direction, the bridge looks like a ladder leading the crowd on it to an unlikely elevated height beyond our visual reach. Or conversely, the bridge may seem to go downward, suggesting that the crowd is marching—or falling—into the unknown void beneath the bottom of the frame. Most intriguingly, given its symbolism of contact and passage, the bridge as Shen depicts it nevertheless presses in like an iron cage, enclosing the crowd in a cramped space.

Shen must have identified himself with the lonely small “maomao” boat drifting on the river. It had been eight years since his attempted suicide in 1949, and he had become more used to being part of the socialist machine. Still, his illustrations reveal that he was distancing himself from either the masses or the bridge leading them up or down, while trying to keep a delicate—and desolate—balance on his own, like a small boat on troubled waters. He was wary about any political movement, but unlike the spring of 1949, he had developed a strategy for coping with it. As the third illustration shows, he willfully erases the bridge and the mass, introducing instead a lonely fisherman fishing. Importantly, reference to time is omitted in the third illustration, a sharp contrast to the time precisely inscribed in the first two illustrations and, by extension, in the essay: “May 30, 1949, 10:00 p.m.”

The three illustrations show Shen Congwen’s effort to minimize, even to the point of abstracting, temporal and spatial indicators in search of a landscape—and mindscape—of his own. With the lonely boat and fisherman in the third illustration, he is making a statement that he has found a way to survive reality. In the late forties, Shen compared himself to a sinking boat. In his May 2, 1957, letter in which the illustrations appear, he writes instead, “[the “maomao” boat] looks so small, so unstable—it barely stays balanced in ordinary times and it rocks up and down even in small waves. But it will never sink, even when big waves come. Judging by its design, it will never sink.”64 There lies beneath Shen’s letter and illustrations something more than a statement of survival tactics. Boat and river constitute the core motifs of his imaginary nostalgia.65 Although Shen’s boat resurfaces in the 1957 illustrations, it has been relocated from the waters of West Hunan to the Suzhou River in Shanghai. One cannot but ask: Would it still have been possible for Shen to send his boat back to his desired land?

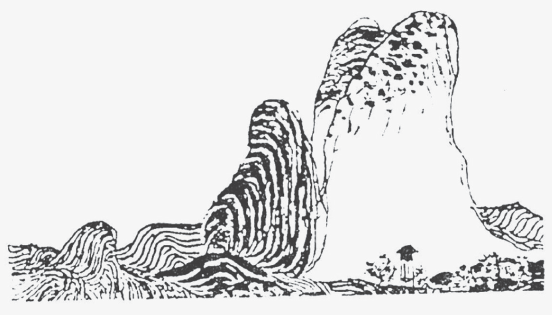

This leads to my last point. The lonely fisherman on the “maomao” boat serves for Shen Congwen as an unlikely link between past and present, imagination and reality. The “hermetic fisherman” (yuyin 漁隱) is one of the most salient themes in traditional Chinese painting and poetry, particularly associated with nonconformist gestures by the loyalist painters of the Yuan dynasty. In such works as “Yufu tu” 漁父圖 (Scroll of fishermen) by Wu Zhen 吳鎮 (1280–1345), one of the Four Great Yuan Painters, the artist features a fisherman or a few fishermen boating on an expanse of water, which suggests a lofty and distant ambiance.66

Moreover, the “hermetic fisherman” is frequently featured in the Xiaoxiang shanshui 瀟湘山水 (Landscape in the area of the Xiao and Xiang rivers), a major genre of traditional Chinese landscape painting traceable to the Tang dynasty.67 Though it generally refers to the lyrical locale conceived of by Chinese literati painters, Xiaoxiang has a specific geographical origin. Both the Xiao and Xiang rivers originate in West Hunan, Shen Congwen’s home region.

By resurrecting within his illustrations the classical motif of the lonely fisherman, Shen Congwen seeks spiritual contact with the ancient literati painters on the one hand and with the landscape of his home on the other. His search carries an ironic undertone, for his 1957 illustrations bear no surface resemblance to either the ideal landscape as projected by the Xiaoxiang painters or the scenery of his hometown region. The modern fisherman is no longer on remote, idyllic waters but on the muddy Suzhou River. Above all, in a society celebrating collective solidarity, hermeticism is deemed self-alienation from the people.

Wu Zhen, Yufu tu 漁父圖 (A painting of a fisherman). Shanghai Museum

Still, by drawing a fisherman fishing alone at night regardless of the daytime excitement and furor, Shen Congwen is doggedly cultivating his own imaginary time and space of quietude. As his letter to Zhang Zhaohe intimates, he knows it is a daunting task, yet he has a reason to be hopeful. “It is interesting to think of the relationship between the small ferry boats and the big ships. According to zoologists, crocodiles often open their mouths wide and let small birds pick the little creatures between their teeth, never heartlessly closing their mouth suddenly. One wonders when they acquired this habit of mutual adaptation.”68

Thus, at the magic conjuration of the third illustration, all tangible objects evaporate into air. Only a fisherman is left, fishing for tiny shrimp at midnight. One wonders where he comes from and how he will make do. At that liminal moment, the fisherman, as Shen would have it, seems to gesture toward something far from the immediate reality. He seems to be fishing on the river of time, ever ready to invite us to sail upstream with him. He might guide us to the legendary point where an ancient fisherman is said to have discovered the Peach Blossom Grove, the Chinese utopia located allegedly in West Hunan.69 Or, even more suggestively, he might take us to the primal scene of Chu lyricism, the dialogue between Qu Yuan and a fisherman. In “Yufu” 漁父 (The fisherman), in the Songs of the South, Qu Yuan roamed along the river after having been banished by Prince Chu. “He wandered, sometimes along the river’s banks, sometimes along the marsh’s edge, singing as he went.” He ran into a fisherman, who asked, “What has brought you to this pass?” Qu Yuan answered, “Because the world is muddy and I alone am clear … and because all men are drunk and I alone am sober.” In response, the fisherman sang:

“When the Ts’ang-lang waters are clear,

I can wash my hat strings in them,

when the Ts’ang-lang waters are muddy,

I can wash my feet in them.”

With that he was gone, and did not speak again.70

滄浪之水清兮,

可以濯吾纓;

滄浪之水濁兮,

可以濯吾足。

遂去不復與言.

A Sartorial Enlightenment

Throughout the fifties and early sixties, Shen Congwen tried out a series of fictional projects that includes at least a novel about his brother-in-law, Zhang Dinghe, who died a martyr for the revolution;71 “fifty stories about Sichuan”; “tales of ten cities,”72 a saga chronicling the changes and continuities of China in the first half of the twentieth century;73 and sketches in the style of Xiangxing sanji 湘行散記 (Notes on a Trip to West Hunan, 1934) and Turgenev’s Notes of a Hunter.74 Shen even wished in 1964 to write about Qu Yuan and Jia Yi, the ancient literati exiled to the south.75 None of these projects was carried out. Meanwhile, from 1953 on, he published steadily on subjects related to material culture and art history. His topics range from brocade to ceramics; lacquer ware; patterns of fabrics; designs of dragon, phoenix, and fish; the art of dyeing; the making of mirrors; decorated stationery; glass handicrafts; painting; paper cutting; and architectural designs.76 Although Shen demonstrates seemingly inexhaustible knowledge, one may still ask: Do the writings represent for Shen a scholarly undertaking or a vicarious literary engagement? How does he come to terms with the difference between a historian’s evidential inquiry and a writer’s imaginary adventure? What are the stakes of writing (art) history at a time when writing as such has already become a treacherous profession?

In 1963, Shen Congwen was commissioned to compile a book on Chinese costume at the suggestion of Zhou Enlai 周恩來, Prime Minister of the PRC. The pretext was that such a book could serve as an ideal gift on diplomatic occasions.77 In eight months, with the assistance of a modest team, Shen worked out a draft of two hundred thousand characters and more than two hundred illustrations. Publication of the book was put on hold at that point, as the political wind had changed direction. During the Cultural Revolution, the manuscript was denigrated as honoring the feudal past ruled by “the dead”; like many other intellectuals, Shen was sent down to a cadre school for reeducation. Miraculously, the manuscript survived the stormy years, and in 1979 Shen was allowed to revise it for publication. When Research on Ancient Chinese Costume was finally published in 1981, seventeen years had passed since its first draft was accomplished.78

A Study of Ancient Chinese Costume (hereafter Ancient Chinese Costume) features a nearly three-hundred-thousand-character narrative and more than eight hundred illustrations; its coverage spans from the beginning of Chinese civilization to the Qing. On all accounts the book represents Shen Congwen’s triumph as an art historian and a literary practitioner. By analyzing countless artworks such as paintings, textiles, clothing, garment accessories, stone carvings, lacquer and ceramic ware, pottery statues, murals, graphic illustrations, funereal objects, etc., many of which had been recently excavated, the book provides visual and textual information about how Chinese have dressed themselves over three millennia and how clothing has “fashioned” Chinese civilization in various ways.

Although its title never spells it out, Ancient Chinese Costume is meant to be a history of one rarely explored aspect of Chinese civilization. Shen was wary about the fact that “history” in the Communist discourse connotes both sacrosanct spell and menacing power. He had been drafted to participate in the project Zhongguo lishi tupu 中國歷史圖譜 (An illustrative account of Chinese history) in 1961, but quickly withdrew when its political agenda became oppressive.79 That he was willing to commit to a new project on ancient Chinese costume, though it was also mandated by the government, suggests that he had found in the mission a way to write about the past as he wished.

The reason has to do with the subject matter. I argue that, as an object that mediates the domains of intimacy and sociality, clothing conveys the felt relations of the civilizing process of a society. It provides Shen Congwen with a unique entry point into history. This history may refer to the dynamics of affectivity as far as contemporary theory is concerned, but Shen would have called it a “history of feeling” in light of his juxtaposition between “a history with feeling” and “a history of actions,” discussed in chapter 1. As Shen points out, clothing was invented at a burgeoning moment of Chinese civilization in response to the humans’ corporeal need; as time moved on, it developed into a rich construct informing a society’s economic, political, aesthetic, technological, gender, and sentimental mutations.80 While “Men till and women weave” (nangeng nüzhi 男耕女織) constituted the quintessential structure of labor division, gender distinction, and social order of ancient China, textiles and clothing were crucial to the functioning of the Chinese state from the Zhou to the late Qing in terms of ritual, taxation, class, and gender power.81 As Shen would have it, although deemed superficial by orthodox historiography, clothing occupies a “soft space” through which body and society, sentience and materiality, domestic affection and civic duty, utility and expenditure are connected and contested. Moreover, insofar as it is where fabric and fabrication interact with each other, clothing serves as the textile and textual manifestation of a social imaginary; as such, it points to the “abstract” formulation of Shen’s lyrical view of history.

The symbolism of clothing has long been embedded in classical Chinese wisdom. Mark Elvin has called attention to the fact that clothing was fundamental to the Chinese idea of culture and propriety; the naked body was deemed neither erotic nor beautiful.82 The Goddess Luozu (Leizu 嫘祖) is said to have first undertaken to raise the silkworm and initiated the technology of sericulture, of which the early Confucian philosopher Xunzi said: “its merit is to clothe and ornament everything under Heaven, to the ten thousandth generation. Thus the rites and music are completed, noble and base are distinguished, the aged are nourished and the young reared.”83 This interest in the relationship between clothing and civility continued to be elaborated upon in the following centuries, to the point where it became common to regard the skill of governing as that of weaving, or to compare canonical texts to valuable fabrics.

Shen Congwen was aware of the political implications of his research subject. After all, in his time, apparel uniformity was enforced so as to emphasize class and gender equality. Read a few chapters into Ancient Chinese Costume, and one would be amused by Shen’s comments on the relationship between fashion codes and state power. But such a reaction would make Shen a mere observer of political and sartorial analogy, and he has something more subtle to offer.

To begin with, Shen Congwen intimates over and over that his research on Chinese costume is not merely an endeavor in traditional historiography. Rather, it is based on his sensorial encounters, visual and tactile in particular, with numerous artifacts surviving the passage of time. Shen had been an amateur connoisseur of Chinese fabric since the forties. He formally started his research on Chinese costume in 1953 and had since seen, and literally placed his hands on, hundreds and thousands of textile objects. According to Shen, any research on the “meaning” of clothing requires in the first place a study of the material process through which clothes are designed, produced, consumed, and encoded into a social discourse. Through the mediation of clothes, we are led to other fabric products, decorative items, and personal paraphernalia. Shen is also interested in objects such as embroideries, apparel accessories (hats, shoes, veils), jewelry, ornamental items, hairdos, fashion designs, cosmetic trends, and furniture styles.

At stake here is Shen’s subtle debate with communist historians in terms of both methodology and ideology. In contrast with his peers in academia, who emphasize either archival studies or intellectual deliberations, Shen situates his research interest in a “lowbrow” area: sartorial culture has been regarded as trivial, if not irrelevant to “true” history. He argues that by studying as well as feeling the materials, he effects a “materialist historiography” of his own. Shen even insinuates that despite his reactionary image, he should be regarded as one who truly follows the ideological mandate of his time. After all, what can be more down to earth than working on recently unearthed objects closely related to corporeal materiality? Thus, during the Cultural Revolution, Shen was able to defend himself by claiming that his study was inspired by Chairman Mao’s materialism.84

Ancient Chinese Costume unfolds following the chronological timeline of Chinese history, but it does not try to cover every period in a comprehensive manner; instead, it focuses on select objects that serve as an index to a time. Shen often starts with a specific item in either concrete form or illustrative representation (drawn from a bronze vessel or a tomb mural, for instance), followed by a narrative interpretation and additional illustrative supplements. As a result, the book reads not like a sequence of tell-all accounts but like a series of vignettes. And yet Shen is able to make these vignettes cross-reference each other, thereby creating a constellation of meanings.

Take a look at a few examples. In a study of the clothes excavated from a Warring States tomb, Shen examines the design and cut of the fashion in such detail that he is able to re-create the process of tailoring. His investigation of an extra cut under the arm of the dress helps him unravel the mystery of ren 衽, a design crucial to the sartorial and ethnic code of the time. He proceeds to explain why such a design can yield a spatial elasticity, adding extra comfort and aesthetic feel to the dress.85 In another case, Shen is attracted to a kind of hat with a long veil (miluo 冪羅) worn by women of the Tang dynasty. He traces its origin and transformations in subsequent centuries all the way to the Qing, when its design bifurcated into two forms, one shaped like a turban with a decorative purpose (zhemeile 遮眉勒) and the other shaped like a square scarf with a weatherproof purpose (gaitou 蓋頭).86 Shen Congwen is also observant about the politics of a certain dress code and its transgression. For example, in the Ming dynasty, members of the laboring class were allowed to dress only in dark brown. Shen notes that by means of inventive dyeing, they nevertheless managed to develop a spectrum of more than twenty shades of dark brown, thus creating a color scheme of their own that resisted the monochromatic code prescribed by the authorities.87

In these cases, without seeing or feeling the objects described, Shen argues, it would have been difficult to discern their material and function, let alone their historical meaning. While visual encounter constitutes the basis of Shen Congwen’s studies, “seeing” may not necessarily result in “believing.” This leads to my next point, that Shen invests his scopic approach with a hermeneutic rigor. For example, the painting Han Xizai yeyantu 韓熙載夜宴圖 (Han Xizai’s nightly banquet), allegedly by the Southern Tang painter Gu Hongzhong 顧閎中 (910?–980?), has traditionally been regarded as a rare specimen of the aristocratic lifestyle during the Five Dynasties era. Shen Congwen points out, however, that the painting could not have been completed before the early Song, for, among other reasons, that the furniture and dinnerware in the painting are of Northern Song style; that many official-like figures in the painting are uniformly dressed in green, a color code applying only to those Five Dynasties (Southern Tang included) officers surrendering to the Song; and that all the attendants have their hands crossed before their chests, a characteristic posture of Song and Yuan etiquette.88

Shen Congwen discerns a similar problem of anachronism in another famous painting, Zanhua shinü tu 簪花仕女圖 (A portrait of ladies with floral decorations), attributed to the Tang painter Zhou Fang 周昉 (?–?; eighth century). In the painting, several court ladies appear with high hairstyles decorated with golden hairpins and wearing semitransparent silk robes, all typical high Tang fashions. But Shen alerts us to the fact that these ladies’ hairdos are crowned with huge floral decorations whose designs became available only in the Song. Moreover, one of the ladies wears a golden necklace outside her blouse, a custom not seen until the Qing. Shen concludes that this painting may have been done by a painter or painters of the Song or later periods, based on an old draft of the Tang, while the suspect necklace must have been added as late as the Qing.

Both examples indicate that, while relying on references such as paintings (and other literary and cultural works) to verify the authenticity of the apparel objects in question, Shen Congwen remains no less vigilant about the reliability of these references. This involves developing a cross-referential knowledge that demands a continually expanding network of sources and data. Shen had demonstrated his scholarship in the forties when challenging the dating of Zhan Ziqian’s Spring Excursion, as discussed in the introduction. In Ancient Chinese Costume, he takes his skill one step further, to examine the truth claims not only of a certain artwork or dress code but also of historiography on its own terms. A historian’s task, accordingly, is not to look at materials as they are but also to look through them in multiple dimensions—as Shen deciphers a Tang robe, a Song hair decoration, or a Qing necklace. The historical paradigm of Shen Congwen’s time regards history as a wholesome entity, so well tailored as to become something like, in the Chinese old saying, a “celestial dress without a single stitch” (tianyi wufeng 天衣無縫). Through his study, however, Shen expresses a different view: history becomes meaningful where the passage of time is being sensed; and the passage of time manifests itself where gaps in the representational system surface and signs of tailoring—designing, cutting, suturing—come into view.

The way Shen Congwen engages with the objects in Ancient Chinese Costume invites a reconsideration of his literary pursuits in the latter part of his career. As described above, Shen struggled to resume his literary activities throughout the fifties and early sixties, to no avail. Along the way he repeatedly expressed his sense of failure, caused not only by political strictures but also by a deep-seated fear of doom.89 In a letter to his brother in 1957, he describes this fear as “invisible, untouchable and yet existing, something that is eroding confidence in and passion for work.”90 Therefore, it must have been a pleasant surprise when Shen discovered in the project of Ancient Chinese Costume a venue through which to rekindle his creative passion. As he puts it in his preface to the book:

In both method and attitude, there is a connection between this book and the literature I created in the first half of my life.… In general, its scope gives one the impression of a full-length novel while its content reads more like a series of essays in discrete styles and segments.91

By comparing Ancient Chinese Costume to a novel or a series of essays, Shen calls attention to the imaginative elements in his research and, conversely, the historical bearings in his textual construct. In his early life, Shen had already conceived of mixing genres such as poetry, prose, fiction, and travelogue together to create a form of encyclopedic scope. Through his account of the culture of Chinese clothing, Shen manages to weave various genres into a rich textual tapestry.

Let us rethink Shen’s claim that each chapter of Ancient Chinese Costume is derived from an object (or a group of objects) that happened to be available at the time of his research. Insofar as each chapter is “occasioned” by the incidental availability of tangible objects, Shen implies the contingency underlying his research. This obliges him to develop a narrative—and historical view—of disparities and coincidences while at the same time liberating him from the constraints of conceptual and ideological sequentiality. Be it a piece of robe, a hairpin, or a cosmetic box, Shen Congwen is able to find in the select object an eye-catching element, something that serves as a clue to the culture of the fashion in question, which in its own turn projects a broader historical and affective context.

Behind the seeming randomness of Shen’s narrative lies an overarching vision that can be described as jijng shuqing 即景抒情, or lyrical evocation at an instantaneous glimpse of the scene. It recalls the narrative format of Notes on a Trip to West Hunan, a collection of sketches of his accidental encounters with figures, events, and scenery on a homecoming trip in 1933. Traveling mostly on the river, Shen assumes the double role of both an informed visitor and an alienated native son in observing and inscribing that which impresses him. His writing also draws freely from personal reminiscences, local legends, and literary allusions, to the point where memory and history, fantasy and fact are intertwined. As his narrative moves on, the random notes gradually form a coherent account of the subtle changes and continuities of his hometown region during the years of his absence.

Three decades after Notes on a Trip to West Hunan, Shen embarked on a different kind of trip in compiling Ancient Chinese Costume. This time, he follows the “long river” of history to the immense, underexplored territory of Chinese sartorial civilization. While his subject may be more academic than before, his style recalls his previous incarnation as a lyrical writer. In other words, what concerns Shen is not just the art object as such but also its evocative power, emotionally and figuratively. The art object effects a chain of associations with other objects, configurations, sentiments, thoughts, and even fantasies at different temporal and spatial conjunctures, such that it takes on the dimension of objective correlative. Through the interplay between wu (object) and qing (feeling/circumstance), Shen thus is able to engage with and disengage from history, which otherwise appears as a teleological, irreversible process.

For instance, in his description of boatmen’s dress in the Tang dynasty, Shen refers to the Tang poet Bai Juyi’s poem “Yanshang fu” 鹽商婦 (Salt merchant’s wife) for a better understanding of their lifestyle; then he moves on to an entry of the Xin Tangshu 新唐書 (New history of the Tang) that records the hardships of boatmen along the Yellow River. The references lead Shen to contemplate the challenges and fatal mishaps these boatmen faced daily, a sharp contrast with the life of the passengers on board. This contemplation may well have been prompted by the popular class consciousness of his day. But for anyone familiar with his early prose and fictional works, a different subtext comes to mind: his account of the life of Tang boatmen reminds us of his numerous descriptions of the boatmen in his hometown region during the Republican era.92 From the old ferryman of Border Town to the old sailor of Long River, these figures carry out their daily routine, experiencing happiness and sadness, as if they were carrying out their fate forever. Through the topic of the Tang boatman’s dress, Shen enlivens the sensorial continuum between ancient times and the modern era. His narrative guides us to enter a contact zone where time projects multiple trajectories and qing, as both feeling and circumstance, becomes a transferable token of communication. Similarly, Shen’s observations of the hairstyles and musical instruments of the southwestern minority dancers in the Han period, and the dyed and embroidered garments worn by the Miao youth in the Qing dynasty, can easily be read in parallel to his sketches of the tribal apparel culture in his hometown region as late as the 1960s.93

More noticeable is the fact that Shen’s sartorial excursion takes him to the various periods of Chu culture, the source of his literary inspiration. Shen makes efforts to describe the garments and cosmetic paraphernalia excavated from the Chu region. By looking at the fabrics and clothes of ancient times, examining the way they are woven and tailored, as well as buried, fragmented, and ruined, he invests them with his own pathos. Again, Shen’s undertaking leads us to the poetics of the Songs of the South:

But a heavy sigh breaks from my sorrowing breast,

and gasping sobs rise, uncontrollable.

I have twisted my longing thoughts to make a girdle;

I have woven my bitter sorrow to make a stomach band.

傷太息之愍憐兮,

氣於邑而不可止。

糺糾思心以為纕兮,

While it is not uncommon for the ancients to compare writing to tailoring, the quote from the Songs of the South is striking for its stress on the inextricable relationship among melancholy mood, sartorial splendor, and poetic refinement.95 It may therefore suggest the poetics of layered fabrication with respect to the precarious political climate.

Finally, we need to revisit Shen Congwen’s “lyrical archaeology.” As described by his student Wang Zengqi, Shen was constantly “amazed [at work] by the beautiful design, incredible color scheme, and miraculous craftsmanship of these objects, above all by those who created the objects. He has a passion not for the things as such but for the human [who created the things].”96 Accordingly, “archaeology” indicates not only Shen’s excavation of material culture and environmental data of a bygone civilization but also his surveying of human affects and imaginations buried in the temporal ruins; “lyrical” indicates as much Shen’s self-reflexive poetic sentiment as his affective response to the vicissitudes of the Chinese mindscape across time.

Still, one needs to keep in mind that Shen’s lyrical archaeology carries a pessimistic undertone. “Not everything that is good will enjoy immortality,” he notes; “as a matter of fact, most insurmountably great and beautiful things have come to be ruined, buried, or thrown into oblivion over time; time is insensitive to human endeavor. Only a very small portion of them, thanks to the factors of chance, have survived and affect on us.”97 Regardless, Shen believes that even from the remnants of artifacts one can discover the abstraction of feeling that illuminates a given historical moment. Instead of the conventional archaeologist, Shen compares himself to a “ragpicker” or even “a beggar woman.”98 Outmoded by modern times, which highlight the value of use and progress, the ragpicker is useless and struggles to get by, finding value in what has been devalued and discarded. Sorting through the everyday trash of history, he takes it as his own task to catalogue vanished dreams and failed promises. Indeed, Shen takes great pride in collecting apparently useless objects and rediscovering their meaningfulness. As late as 1983, he remembered how he had been singled out as a “negative example” for collecting two objects deemed lacking in “historical significance,” yet these items eventually proved to be crucial evidence about ancient Chinese astronomy and the textile industry respectively.99

Shen Congwen’s self-description uncannily echoes Walter Benjamin’s notion of “ragpicker.” Both seek to invoke a polemic of aesthetic redemption when faced with the monstrous atrocities of history. However, whereas Benjamin’s ragpicker walks the fine line between “a romantic ambivalence about the past and a revolutionary nostalgia toward the future,”100 Shen plows through the trash of history regardless (or because?) of the aftermath of revolution. For him, the postrevolutionary era turns out to be equally, if not more, vandalistic than the prerevolutionary era. How to rescue history from the “revolution” became his hidden agenda. Benjamin’s yearning for either a revolutionary poetics or a messianic epiphany ended with an anticlimax; he committed suicide when trapped by the Nazis in 1940. Shen tried to kill himself on the eve of the Chinese Communist takeover in 1949, only to survive and become a provocative chronicler of the material past in the new era.

However undesirable, this new political circumstance drove Shen Congwen to reaffirm the necessity of lyrical imagination against all odds. For various reasons, “Abstract Lyricism” was never finished. With Ancient Chinese Costume, Shen Congwen manages to take up where “Abstract Lyricism” leaves off. He tells a story of Chinese history by literally piecing together the “rags” drawn from different periods and sites. He understands that the human bodies that once wore—or inhabited—the clothes have long vanished, and that the clothes once “animated” or even empowered by their owners are restored to the state of materiality. Glamorous or humble, the clothes, or actually the fragments of the clothes, under Shen’s examination are testimonials to the power of both human creativity and the ruination of time.

Thus, thirteen years after his attempted suicide, Shen made peace with himself through the study of ancient Chinese costumes. As he wrote to Zhang Zhaohe in 1962, “A rare talent does not mean a useful talent; he may be left unattended to at a certain time, and it was not uncommon he might be ruined all together. The times of Du Fu, Bai Juyi, and Cao Xueqin all saw talents underused and therefore reduced to nothingness.”101 But just as he bade farewell to his literary career, Shen started something new. This new “literature” can be appreciated only in light of the traditional sense of wenxue 文學, a learning of the “patterns”—wen 文—as manifested not only in belles lettres but also in the schemata from the poetic mind (wenxin 文心) to artifacts, cultural constructs, as well as cosmic rhythms. Accordingly, through the patterns, fashions, designs, and constructs of clothes, Shen rediscovers what wenxue could mean.

Once the subjects of the world, whatever they may be, find their way into this eternally youthful heart, they partake of a kind of poetic sensibility. They are waiting for their chance to take form!… [This form] can be described as a total outcome of life. It comprises nuanced personalities, complex experiences, hundreds of books, thousands of paintings, numberless figures of eccentricities and differences, lives beyond imagination, and the events and people in life, all mixed together as a result of living for sixty years.102

This is a moment of enlightenment for Shen Congwen, in which he goes beyond the narrowly defined paradigm of May Fourth and Maoist literature and creates a new form on his own. Still, resounding somewhere in his lyrical archaeology of ancient clothes are the lines of Tao Qian:

Wet clothes are no cause for regret

so long as nothing goes contrary to my desire.103

衣沾不足惜,

但使願無違。