Death in the Gloaming

BY THIS TIME and in part because no support had been sent his way, Barksdale was “almost frantic with rage,” while attempting to prepare his hard-hit troops for yet another offensive effort to smash through yet another Yankee line. Above all, he knew that he had to get the attack beyond Plum Run rolling once again. One 126th New York captain never forgot the sight of Barksdale during the general’s last moments of life: “Gen. Barksdale was trying to hold his men, cheering them and swearing, directly in front of the left of the 126th near the right of the 125th who both saw and heard him as they emerged from the bushes.”484 Private Joseph Charles Lloyd, 13th Mississippi, recalled the sight of the mounted Barksdale encouraging the boys onward, yelling “Forward through the bushes.”485

Incredibly, Barksdale surged forward in yet another attack with only a portion of his troops beyond Plum Run, “leading his command in a desperate charge on our left centre,” in the words of Yankee Robert A. Cassidy. Large numbers of Mississippi Rebels charged up the ascending slope of Cemetery Ridge with cheers.486 The resurgent Mississippians lashed back at their New York attackers, threatening to turn the right flank of Willard’s brigade and pushing on toward McGilvery’s Reserve Artillery and Cemetery Ridge.

In the 17th Mississippi’s ranks on Barksdale’s right, Private Abernathy described the counterattack of his Mississippi Rangers, how “Jim Crump sprang over him, called for a ‘forward charge with bayonet’ and the line went forward leaving a ghastly row” of dead and wounded, while “Arch Lee had run up with the flag of the old 17th. On it had been embroidered the names of the battles in which it had fought. Manassas, Leesburg, Yorktown, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, Gaines Mill, Savage Station, Fraser’s Farm, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Fredericksburg, and then the cry for another forward movement.” All the while, the savage, close-range fighting swirled to new furies among the brush-covered and second-growth timber amid the bloody swale of Plum Run. Like the open fields over which the Mississippi Brigade had charged all afternoon, the swale, once a pristine and picturesque creation of nature, had been transformed into a gory, killing ground, where large numbers of Mississippi boys fell.

By this time, scores of Barksdale’s men had fallen during this lethal duel of musketry. Outflanked on the left by attackers of the 111th and 126th New York, the first hard-hit 18th Mississippi soldiers, without ammunition or luck, sullenly began to retire to the west.487 However, in the smoky confusion, most surviving Mississippians remained in place in defensive positions, reloading and firing as long as rounds in cartridge boxes remained, while Barksdale continued to urge his troops—at least those who followed him, mostly 13th Mississippi soldiers—up the open slope on Plum Run’s east side in a last-ditch effort to gain Cemetery Ridge. After having fought all afternoon and being depleted of ammunition, however, additional Mississippi Rebels on the left were forced to withdraw. This was even as more counterattacking 126th New York soldiers who continued to attempt to turn Barksdale’s left flank were killed by the Mississippians’ accurate fire.

While additional Mississippi soldiers retired to consolidate new defensive positions on Plum Run’s west side, the New York brigade surged ahead upon seeing many of Barksdale’s hard-hit Rebels redeploying. As Lt. Colonel Crandell, 125th New York, recorded in his diary, when the New York brigade charged and “entered the bushes we went firing as we advanced [and] with a yell we sprang forward [and] we drove them at the point of the bayonet with an impetuousty that drives irresistibly onward. The ground we charged over was covered with killed & wounded but we had done what all the regiments had failed to do at the point of the bayonet.” Believing that victory had been won, the New Yorkers charged across the creek to exploit what they believed was their greatest battlefield success to date; in fact, by halting Barksdale’s Brigade, something no other Union formation had been able to do that day.

Instead they ran into a wall of fire. The Mississippi Rebels had quickly reformed on the west side of Plum Run, and they now delivered a punishing volley with what little ammunition remained in their cartridge- boxes. Falling wounded, Colonel MacDougall, commanding the 111th New York, paid a high price for turning Barksdale’s left flank, writing how “so severe was the fire to which we were subject that my loss in that charge was 185 men killed and wounded in less than 20 minutes, out of 390 taken into the fight.” And Lt. Colonel Levin Crandell lamented in his diary how his 125th New York “lost 135 men out of a little less than 400.”488

The high losses resulted from the swirl of confused fighting at close-range amid the underbrush and thickets along Plum Run’s bottoms, where the dense summer foliage and layers of smoke, stagnant in the breezeless July heat and humidity, hovered low on the ground. In the confusion of the close-range, back-and-forth combat, some prone Mississippians, lying in the underbrush, turned to fire into the backs and flanks of the New Yorkers, who charged over the creek. Fighting beside his comrades of The Kemper Legion, 13th Mississippi, Private Joseph Charles Lloyd was shocked to look around and “see the enemy bursting through the bushes.” While some Mississippians, especially on the left, had been either outflanked or surrounded and then forced to surrender, most of Plum Run’s defenders remained fighting. However, the shooting down of New Yorkers while they were taking prisoners incensed Willard’s men, who incorrectly believed that Barksdale’s men were giving in. But most Mississippi Rebels had no thought of surrender, especially with Cemetery Ridge so near and yet within reach.489

However, Longstreet, who had been stubbornly against Lee’s concept of taking the offensive all day, and had lost control of his troops and the fast-paced tactical developments, had mentally disengaged from the of-fensive effort, unlike Barksdale and his men who were going for broke.490 Tragically, hundreds of Mississippi Brigade soldiers had already been cut down in part because of the lack of unity in tactical thinking between the offensive-minded Lee and the defensive-minded Longstreet, whose dispute about how best to reap victory at Gettysburg now came back to haunt the best efforts of Barksdale, Humphreys, and their hard-fighting men.491

After the war, Longstreet, as if feeling guilty for his failure to adequately support Barksdale’s all-out offensive effort and early pulling the plug on the assault that in part led to the Mississippi Brigade’s repulse, wrote to McLaws to explain how “this attack went further than I intended that it should, and [would result] in the loss of your gallant Brig -adier Barksdale. It was my intention not to pursue this attack if it was likely to prove the enemy’s position too strong for my two divisions. I suppose that Barksdale was probably under the impression that the entire Corps was up.”

Considering Longstreet’s words, it is here worth considering whether “Pickett’s Charge” could indeed have gone down in history as the climactic, victorious blow struck for Southern arms—if it had been launched in the twilight of Day 2 at Gettysburg rather than on Day 3. At the moment late on July 2 when Barksdale’s men were grappling with a severely depleted Union line on the slope of Cemetery Ridge, one can only imagine the effect of 4,500 fresh Virginia troops coming up behind them in support. No force at Meade’s disposal would have been remotely able to prevent a clear breakthrough by Pickett’s eager, unbloodied brigades led by Armistead, Kemper, and Garnett. Further, they would have had a nearly unmolested approach march, able to release their full fury right at the very foot of a haphazard Union defense line.

Pickett’s division had begun arriving near the battlefield around 2:00 that day, and perhaps by 5:00 it was fully assembled. Like A.P. Hill’s division after its long march to Antietam, it could have gone straight into battle; more so if it had begun its march a few hours earlier and thus could get some needed rest. However, Lee apparently never considered the option, sending perhaps the most fateful order he ever issued: “Tell General Pickett I shall not want him” on July 2.492 Pickett was thus kept in reserve, saved “for another day,” while it was on the very afternoon of his division’s arrival that the Army of Northern Virginia was within a hairs’ breadth of winning the most important battle of the war.

Given all the mistakes made at Gettysburg, small and large by both sides, the “what if’s” of the battle are too numerous to count and tend to only lead to as much frustration as fascination. However, one must recognize that the often-castigated Longstreet may have been correct in the first place after he learned that he was to launch an offensive on July 2, and mused to John Bell Hood, “[Lee] wishes me to attack; I do not wish to do so without Pickett. I never like to go into battle with one boot off.” There can be little doubt that if Pickett’s fresh division had been available to throw into the fray in support of Barksdale, the battle would have been won by the South. Among the cascading effects of a clean breakthrough of the Union left-center by Longstreet would have been increased contributions by Ewell’s and A.P. Hill’s corps, who would have faced a severed Army of the Potomac on the verge of panic that evening, rather than virtually unassailable heights.

As it stands, Longstreet later described the attack of his First Corps troops on Day 2 as “an unequal battle,” but this situation was far more valid in the Mississippians’ case than for any other Confederate command that afternoon. Without exaggeration, “Old Pete” maintained that “in this attack Hood’s and McLaws’ Divisions did the best fighting ever done on any field” during the four years of war. And no brigade of either division fought harder and longer to achieve more significant gains than Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade.

As the climax of Longstreet’s offensive on the second day of Gettysburg unfolded, the Mississippi Brigade continued to apply pressure on its own, after Barksdale had ordered, “Forward through the bushes!” At the head of his troops to the 18th Mississippi’s right, Barksdale encouraged his men onward, especially his own 13th Mississippi in the center, and at least part of the 17th Mississippi to its right, threatening to break yet another Yankee line. If possible, Barksdale was now the one leader yet capable of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat. Consequently, he “was frantic in his efforts” to push the attack all the way to Cemetery Ridge.

But one especially enterprising Union colonel, George Childs Burling, who now led his rallied mostly New Jersey brigade, Humphreys’ Division, prepared to personally checkmate Barksdale’s desperate bid to win it all. This opportunistic Union colonel, born on a farm in Burlington County, New Jersey, knew that drastic action needed be taken to somehow reverse the surging high tide of Confederate fortunes. By this time, any lingering romantic concepts about chivalry in this first of all modern wars no longer existed in such a key situation, when so much was at stake. Upon first sighting the foremost leader of the Mississippians’ charge, Burling targeted this dynamic, mounted officer for immediate elimination.

Before his troops, the Mississippi general was relatively easy to pinpoint by the foremost New Jersey soldiers, who had rallied along with other Third Corps troops, including “Excelsior Brigade” men. Besides riding up the open ground east of Plum Run at the head of his attackers, Barksdale also stood out because of his distinctive long flowing locks of gray hair that streamed down to his shoulders. At the top of his voice, the forty-two-year-old general was in “our midst,” recalled Private Lloyd of the 13th Mississippi, yelling, “Forward!” Feeling that decisive victory was within his grasp, General Barksdale shouted, “They are whipped. We will drive them beyond the Susquehanna.”

Barksdale’s mounted presence before his onrushing troops was awe-inspiring to the boys in blue. But the astute New Jersey colonel, who knew what it took to win decisive victory this afternoon, was not admiring his counterpart in gray. Instead of allowing chivalry to muddle his tactical thinking, Burling wanted to kill the Mississippi leader, who was encouraging his troops in his desperate bid to win the war before sunset. Colonel Burling called for an entire company of his best New Jersey marksmen, perhaps as many as 50 fighting men. He ordered them to level their Springfield .58 caliber muskets and unleash a concentrated volley at the mounted Barksdale.

However, eager to gain recognition, several other Union leaders took credit for directing a concentrated fire upon Barksdale. The 11th New Jersey, which had already taken a severe beating from the blazing Mississippi muskets in the struggle along the Emmitsburg Road, had rallied by this time. Brig. General Joseph Carr gave Company H, 11th New Jersey—which had suffered more than 50 percent casualties, mostly at the Mississippi Brigade’s hands—a special mission. Above the roaring guns, Carr shouted to every Company H veteran to “bring down the officer on the white horse!” Another account has it that Captain Ira W. Cory of Company H ordered all his men to fire at Barksdale. But in fact, Cory and his men only killed an unlucky Mississippi staff officer, mounted on a gray horse and wearing a Zouave fez in triumph. The finely uniformed officer of Barksdale’s staff went down with five bullets in his body.

Another account gave credit for targeting of Barksdale to the 126th New York, on Willard’s right, when an entire company fired their rifles at him. And a 126th New York captain wrote that his troops and those of the 125th New York “both fired at him and he fell hit by several bullets.” Another New York soldier later told Henry Stevens Willey of the 16th Vermont that “during the hottest of the battle [General Barksdale] came out and tried to rally his men and that he had a star on his collar [and that] he had a splendid chance so he fired on the General and saw him fall.” And Colonel Norman J. Hall wrote, “The rebel Barksdale was mortally wounded and two colors left on the ground within 20 yards of the line of the Seventh Michigan Volunteers.”493 Under the circumstances, the honor of having made the decision to kill Barksdale in a desperate effort to take the steam out of the Mississippians’ attack was eagerly sought by quite a few victors years after the war.494 However, another Union soldier, who saw the general close-up after he fell, believed that Barksdale was cut down not by musketry but by a canister round from one of McGilvery’s guns.495

Clearly, by this time, Barksdale was living very much on borrowed time and tempting fate in leading the attack across Plum Run. As a mounted brigadier general with three stars on his jacket’s collar, long conspicuous in riding before his troops, it was nothing short of a miracle that Barksdale had escaped harm so far after leading the attack over such a long distance. Willard’s New Yorkers in particular wanted revenge for the Harpers Ferry disaster by killing the Mississippi general most responsible for orchestrating their supreme humiliation.496

Regardless of which troops fired the deadly volley and which commander deserved recognition for issuing the final order that toppled Barksdale from the saddle “in a field, no trees about,” in Private John Saunders Henley’s words, the assigned veterans in blue took steady aim on the daring brigade commander. At least one, perhaps more, Union officer roared “Fire!” above the crashing musketry. A well-aimed volley exploded from the leveled row of guns, rippling down the blue line, as a sheet of yellow flame leaped toward “Old Barks.”

In a split second, projectiles ripped through Barksdale’s uniform, splattering gray wool with bright red in the thin, fading July light. Minie balls smashed through his left leg about halfway between the knee and ankle, and another bullet ripped through Barksdale’s other leg. But the general’s stocky 240-pound frame absorbed the shock, and he bore up to the pain. So many minie balls streamed around Barksdale that even the blade of his beautiful saber was broken when he was holding it high over head to encourage his troops onward. In disbelief, Captain Harris Barksdale described the awful sight when his uncle was hit. He wrote how “Gen. Barksdale was wounded, and he reeled but did not halt. He moves on with his band of heros. Onward! and the fourth line is met and vanquished—can nothing stop these desperate Mississippians?”

During the final, but brief, penetration of the New York line in this sector, a piece of canister from the roaring Union field piece positioned on the high ground of the Plum Run Line tore through the general’s left breast, knocking Barksdale off his horse. Because he was so far ahead of his troops and due to the thick smoke of battle and Plum Run’s dense thickets, few, if any, of his soldiers saw Barksdale’s fall, unlike the boys in blue. Yankee Private William M. Boggs never forgot that as “our attention was directed to a general officer leading the first line to the attack and we distinctly saw him fall.” And one Federal officer described how the Mississippi Brigade had “carried everything before it with cyclonic force. I saw brave General Barksdale fall from his horse leading his men and when he fell I could not help shedding a tear at seeing so brave and valorous a soldier killed [as by this time the Mississippians] had us badly whipped.” Serving as one of Longstreet’s couriers, young William Youngblood formerly of Colonel Oates’ 15th Alabama Infantry, recalled how General Barksdale was putting “spurs to his horse [and] dashed a little ways along his line, giving the order to charge at double-quick, when I distinctly heard a shot struck him and saw him fall from his horse.” Youngblood paid a high compliment in declaring that “no troops were ever commanded by a braver man than General Barksdale.”497

The inspirational sight of Barksdale leading the way, which had emboldened Magnolia State attackers all afternoon, was no more. As could be expected, Barksdale’s fall took much of the steam out of the Mississippians’ final offensive effort. One Yankee described how, “His fall—at the very moment when the presence of a commanding officer is most required to encourage men to renewed exertion and sacrifice—was “a severe blow, causing his attackers to fall back.498

Even now, however, Barksdale was down but not out. Wearing a fine cotton or linen shirt of white, now splattered in red, with Masonic emblem stubs under his gray coat, he remained conscious. He yet breathed life, but it was severely labored. As could be expected, the wound to his left lung made the general’s breathing difficult. All that Barksdale could now do was hope and pray that his injuries and multiple wounds were not mortal. However, like the once-seemingly unstoppable momentum that had propelled his assault eastward, Barksdale was already slowly dying, after making aa supreme offensive effort unmatched by any of Lee’s lieutenants on this day. Adjutant Harman, 13th Mississippi, described in a letter how Barksdale “was mortally wounded about the time the Brigade fell back. Jack Boyd was with him at the time he was shot and he and one or two of our boys tried to bring the Gen’l. off the field, but being a very large man and mortally wounded he begged them to leave him where he was which they finally did.”

Private Boyd attempted to comfort the still-conscious general, whose thoughts remained focused on the battle’s outcome. Barksdale now issued his last directive: order Alexander’s artillery up to support his boys in their final desperate bid to gain Cemetery Ridge’s crest. Then, with the counterattacking bluecoats only fifty yards away, Boyd left Barksdale, whose lung wound emitted “a sputtering sound,” where he had fallen. Boyd now rode away on his new mission to secure “long-arm” assistance for the hard-fighting Mississippians before it was too late. A short time later, wounded in the arm, Private Lloyd of the 13th Mississippi found the general splattered in blood. He described the horror of discovering “Old Barks” when, “I hear a weak hail to my right, and, turning to it, find General Barksdale, and what a disappointment when I hold my canteen to his mouth for a drink of water and found a ball had gone through and let it all out. I took his last message to his brigade and left him, with the promise to send litter bearers.”499

Barksdale’s mortal wound meant much more than just the fall of one of Lee’s brigadier generals. In many ways, his fall symbolized the zenith of not only the Mississippi Brigade’s attack but also the real “High Water Mark” of the Confederacy at Gettysburg. In leading the charge that brought the Confederacy closer to decisive success than ever before, Barksdale’s fall just east of Plum Run marked the zenith of the Army of Northern Virginia’s most devastating attack and two hours of perhaps the best fighting of the war.

By this time, Barksdale’s units of both wings had been cut to pieces, after capturing one position after another, smashing through numerous Union commands, and battling for most of the bloodiest afternoon in the Army of Northern Virginia’s history. While leading the 13th Mississippi, Colonel Carter had been killed when four minie balls tore through his body, while his trusty “right arm,” Lieutenant Colonel Kennon McElroy, the former captain of the Lauderdale Zouaves, was hit in the shoulder. And the third in command of the 13th Mississippi, Major Bradley, was shot in the ankle, knocking him out of action.500

Meanwhile, the survivors of the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi were now caught up in a simultaneous scenario of fighting, withdrawing, or surrendering in the noisy confusion, as the onslaught of Willard’s fresh regiments finally turned Barksdale’s left flank, swarming into the underbrush-filled swale in greater numbers. Lieutenant Richard Bassett of the 126th New York described the carnage: “While we were crossing the ravine, I noticed [the colors] faltered, and finally fell; directly they were raised again and went on [but then] my dear brother [Color Sergeant Erasmus E. Bassett and] the boys were falling all around me …” After cutting down more bluecoat attackers, Mississippi Rebels fought hand-to-hand amid the blinding layers of sulfurous smoke that choked the low ground along the blood-stained stream.

Meanwhile, even more Mississippi boys fell during a brutal struggle of attrition along Plum Run. One half-dazed survivor, Captain Harris Barksdale, described the undeniable reality presented by the counterattacking Federals: “Will nothing stop them,—Yea, death will do it and had already done it!—Look up and down the lines! Where are the fourteen hundred men that left the woods, now a mile in the rear? From that point to this they strew the ground while it drinks their blood, and not five hundred have gone this far … they are scattered over the ground, like a picket line, vainly endeavoring to move forward.”501

However, following Barksdale’s final orders to hurry forward Alexander’s artillery and evidently not seeing his fall, die-hard Mississippians in the line’s center continued to charge recklessly onward beyond Plum Run in a last-ditch attempt to capture Lieutenant Colonel McGilvery’s booming cannon to the east. With Willard’s brigade applying the most pressure on the flanks, the attackers now surged only from the brigade’s center, some 13th and 17th Mississippi soldiers, who were not aware of Barksdale’s fall. However, the Plum Run Line guns easily wiped out the foremost attackers. In the words of one Mississippi Rebel, “Thinned by the storm which swept down with such terrific fury from the ridge, the advance line staggered and began to waver.”502

Private Nimrod Newton Nash, along with a few Company I comrades of the 17th Mississippi—and a few soldiers of other companies— in the brigade’s center, charged up the open slope toward Cemetery Ridge, targeting one of McGilvery’s batteries in the fading light. But the attack of the determined Minute Men of Attala and an unknown number of other 17th Mississippi soldiers was quickly cut to pieces in the open field by blasts of canister. In a letter that described the short-lived final assault up the open western slope of Cemetery Ridge, Sergeant Frank M. Ross, 17th Mississippi, penned in a letter how Private Nash “fell while nobly defending his country in a charge on one of the enemies batteries near sunset.”503 Meanwhile, the tough New Yorkers of Willard’s brigade continued to gain even more of the tactical advantage. Corporal Harrison Clark grabbed the regimental colors of the 125th New York, when the color bearer was shot down. He then led his men toward the row of flame erupting from the blazing Mississippi rifles, earning the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroics.504

Along the blood-stained bottoms of Plum Run, a number of surviving Mississippians, in the words of Captain Harris Barksdale, were unnerved by the shocking sight of “General Barksdale’s horse seen galloping over the field. Their general has fallen, and they fall, sullenly backward, contesting every inch of ground. It was known to the men that their beloved general had fallen, wounded or dead, within the lines of the enemy. Their grief was intense, and those brave men wept like children.”505

Meanwhile, flurries of fighting continued to rage in the smoke-laced thickets and dense stands of willows, when larger numbers of cheering New Yorkers charged through Plum Run’s environs with bayonets at the ready, firing on the run, and mopping up the last clumps of resistance. Angry over taking high losses, the past Harpers Ferry humiliation, and the belief that a number of Mississippians who had surrendered had turned to shoot down their comrades from behind, some 126th New York soldiers became vengeful. Evidently, in consequence, a few wounded Mississippians were shown no mercy, being shot or bayoneted by enraged New Yorkers, who delivered the coup-de-gråce to some defenseless men who lay not far from Barksdale.506

Even worse, the wounded Barksdale also may have received rough treatment at the hands of some New Yorkers, whose own fighting blood was up after having lost so many good men. He was left alive, and remained defiant. Even with mortal wounds, Barksdale cursed the Yankee victors, and refused medical treatment from the boys in blue.507 At least one officer, Captain Charles A. Richardson, 126th New York, believed that Barksdale was harshly treated. The general suffered immensely from the wounds in the chest and “in the leg [that] produced a fracture which caused considerable pain … .”508

Colonel Willard’s counterattack ended the final offensive effort of Barksdale’s left wing, stopping the day’s most serious threat.509 However, Willard himself would not survive to savor his triumph. While leading his men in pursuit of the Mississippians, as they sullenly fell back to the main Confederate line, he was hit full in the face by a fragment of shell and died instantly. Barksdale’s only support in his last-ditch attack, Alexander’s artillery, still firing away from the Peach Orchard, had claimed a measure of retribution for the fall of their champion.

At the Peach Orchard, Captain Charles Squires, Washington Artillery, witnessed the return of Lt. Colonel John Calvin Fiser, 17th Mississippi, “just out of the fight. He had received two wounds in the leg and a bullet had passed through his cheek [but] he did not fail even under these distressing circumstances to call to me that he had captured the guns he promised me.”510 Not only faith in achieving victory but also the striking good looks of this fine officer were never quite the same after taking this nasty wound. But at least Fiser, the young merchant and promising officer from Panola, had survived the worst horrors of Gettysburg.511

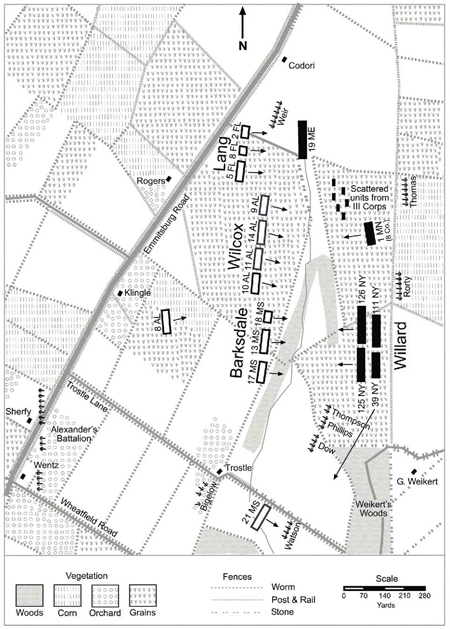

Map courtesy of Bradley M. Gottfried