“We are going into Yankey land”

IRONICALLY, FOR THE young men and boys of Barksdale’s Brigade, Lee’s Pennsylvania invasion first evolved from developments in faraway Mississippi. After a failed offensive the previous winter, the ever-resourceful General Ulysses S. Grant had now arrived on the doorstep of the vital Mississippi River port city of Vicksburg, the most important strategic point in the western Confederacy. His was part of a triune Union thrust that season, along with Hooker’s drive against Richmond and Rosecrans’ impending offensive in central Tennessee. The Army of Northern Virginia had already taken care of its end of the task—defeating Hooker at Chancellorsville—so now the problem in grand strategy was how to turn back the Union offensives in the west.

During two high-level May 1863 conferences in Richmond, Lee was firmly against the idea of sending reinforcements from his own army to Mississippi in an attempt to save Vicksburg. They would arrive too late to relieve the siege and, not having their full trains via rickety Confederate rail lines, would be unable to swing the balance against Grant’s rapidly growing army with its secure supply line on the river. Longstreet proferred the idea of splitting off part of the Army of Northern Virginia to effect a concentration against Rosecrans, in order not only to destroy the Army of the Cumberland but to disrupt Grant’s concentration against Vicksburg by calling him to the defense of the Ohio Valley.

Lee remained convinced that another decisive victory in the east by his own army would more than offset Federal gains in the western theater. And the great victory at Chancellorsville had put him in a unique position: he had not only inflicted severe losses, if not demoralization, on the Army of the Potomac, but his army had actually grown stronger afterward with the return of Longstreet and his two divisions (Hood’s and Pickett’s) that had missed the battle. Combined with the fact that Hooker had just lost thousands of men to expired enlistments, Lee was now closer to numerical parity with the Federals than he had been in a year. He now saw an invasion of Pennsylvania that threatened Philadelphia, Harrisburg, Baltimore, and Washington as the best solution to the Vicksburg dilemma. Even if Vicksburg was lost to Grant, then the blow could be more than negated by a decisive success won on northern soil.84

When word came that Pennsylvania-born General John C. Pemberton, a Jefferson Davis crony of relatively little tactical ability, was bottled up in Vicksburg, a final crisis meeting was held in Richmond on May 26. At Davis’ invitation, Lee articulated his strategic views at length to the Confederate cabinet. While Davis wanted to dispatch troops west to General Joseph Johnston’s forces in Mississippi for a last-ditch attempt to relieve Vicksburg, Lee convinced the cabinet, by a resounding five-to-one vote, and even Davis himself, to embrace his strategic thinking. Forcing a crisis on the Union in the east would be the quickest, most efficient way to draw off pressure on other points in the Confederacy. Further, carrying the war to northern soil would relieve tired Virginia of the burden of supporting the contending armies, while providing a bountiful new source of supply to the Confederates. Finally, Lee made the point that the South could never hope to win the war by continuing on the strategic defensive. Every time he turned back a Federal offensive they simply withdrew behind river lines or into the fortified environs of Washington so that he could not follow up his victories. Only by taking the offensive himself could he hope to achieve a truly war-winning battle.

Thus ironically, as a strange fate would have it, the subsequent role of Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade at Gettysburg had been dictated by the crisis in their own home state.85 Instead of attempting to save Vicksburg directly, the Army of Northern Virginia would seek to force the Federal army in the east to look to its own salvation, as the Confederates embarked on their most risky gamble to date. Lee knew that the best chance to win the new nation’s independence was by reaping a decisive victory north of the Potomac, while his confident army yet possessed the capability to do so.86 Private Nimrod Newton Nash, 13th Mississippi, and his comrades were convinced, as revealed in a June letter, that “Genl Lee is too smart to bee [sic] fooled by a Yanky.”87 With high hopes for reaping significant gains not won during the Maryland campaign less than a year before, a confident Army of Northern Virginia launched its second invasion of the North on June 4, 1863.

After Stonewall Jackson’s death the Army of Northern Virginia was divided into three corps, instead of the previous two, for greater tactical flexibility. Barksdale’s Brigade remained in Lafayette McLaws’ Division, Longstreet’s First Corps, which also included the divisiions of John Bell Hood and George Pickett. Richard Ewell was named commander of Jackson’s Second Corps, for virtue of having been Stonewall’s chief lieutenant during the Valley Campaign and on the Peninsula. Ambrose Powell Hill was given command of a new Third Corps that consisted of his own division (now under Dorsey Pender), Richard Anderson’s Division from Longstreet’s Corps, and a newly formed division under Harry Heth. Preceded on the flank by the cavalry under Jeb Stuart, thousands of Lee’s Rebels, cocky and lean like hungry wolves, pushed north from central Virginia’s depths. Pushing through the Shenandoah Valley, employing the towering Blue Ridge as a heavily-forested screen of green, the Confederates waded across the cold waters of the Potomac River and then moved into Maryland beginning on June 19.88

Confidence soared through Barksdale’s ranks during the relentless push north. The veteran Private Nash, who was fated to be killed at Gettysburg, wrote to his wife Mollie in a June 7, 1863 letter, “We are going into Yankey land [and] I hope we will and that we will scare some of the blue bellies as bad, or worse, than they have scared some of our people.”89

Foremost in Lee’s mind was the painful knowledge that his increasing losses, even in victories like Chancellorsville, were leading the Confederacy down the road to certain extinction. The manpower-short South would slowly die from a lengthy war of attrition, suffering losses that could not be replaced, while the much larger North could easily replace its losses while only increasing its gigantic advantage in manufacturing. As Lee wrote to President Davis in a realistic assessment of the South’s situation, “Conceding to our enemies the superiority … in numbers, resources, and all the means and appliances for carrying on the war, we have no right to look for exemptions from the military consequences of a vigorous use of these advantages.”90

In short, the Confederacy needed to rely on skill and valor on the battlefield while it still could, before the arithmetic of Union material and numerical superiority overwhelmed it. And for this, Robert E. Lee needed to hold the initiative, forcing the Federal army to battle on his terms. If the Army of Northern Virginia invaded the north, the Army of the Potomac would be forced to fight it on open ground, without first securing a line of retreat for itself. If a victory could thence be won by the Confederates, it could be the decisive battle of the war.

As related verbatim by General Isaac R. Trimble, Lee’s ambitious tactical plan on northern soil was based upon the sound premise that the pursuing Army of the Potomac “will come up, probably through Frederick [Maryland]; broken down with hunger and hard marching, strung out on a long line and much demoralized, when they come into Pennsylvania. I shall throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back on another, and by successive repulses and surprises before they can concentrate, create a panic and virtually destroy the army.”91

It was a good plan, providing the best formula for achieving a victory to end the war in the Confederacy’s favor.92 And Lee’s vision of a decisive success on northern soil was shared by his men. In the words of one confident Virginian in a letter, “I think we will clear the Yankees out this summer.”93 And a 13th Mississippi private who waded across the Potomac River’s waters, only about two feet deep on June 26, Private Nash, was convinced on June 28 that “I think we will have Capitol (Harrisburg) ere long.”94

The invasion began with a nifty success, when Ewell’s Corps nearly obliterated three Union brigades at Winchester in the Shenendoah. With fire and maneuver he forced 7,000 Federals out of their stronghold, then caught them on their retreat, capturing nearly 4,000 men plus immense stores. Any doubts that the legendary Stonewall had not properly been replaced were temporarily put on the shelf. Afterward, Ewell’s Corps spread out into Pennsylvania and was soon at York and Carlisle, on the very doorstep of Harrisburg. Longstreet’s Corp followed Ewell’s, concentrating on Chambersburg, and then A.P. Hill’s new Third Corps crossed the Potomac. Union General Hooker, who first wanted to lunge at Richmond once he sensed the Confederate army’s movement away from his front, was instead instructed by the authorities in Washington to rush to follow the Rebel movements.

But then Lee’s carefully laid plan began to go awry, in part by his own decision-making. With Lee’s permission, General Stuart, who commanded the army’s highly trumpeted cavalry corps, galloped away from the army toward Washington, D.C., on the most ill-timed of all Confederate cavalry raids. Stuart rode off with more than 5,000 veteran troopers, attempting to encircle Hooker’s army, and for a week his cavalry remained absent from the Army of Northern Virginia at the most critical time. On the eve of the most important battle in American history, Lee was thus blinded, without his cavalry to inform him of Union movements.95

Thus the first word that Lee gained about the Army of the Potomac’s whereabouts came not as usual from Stuart and his companies of experienced scouts, but from a grimy-looking actor-turned-spy named Henry T. Harrison. Some of Barksdale’s men almost certainly knew Harrison, who had served in the 12th Mississippi until discharged with a medical disability in November 1861.96 On Sunday night June 28, Harrison presented his invaluable intelligence to Lee at Chambersburg, just west of Gettysburg. Naturally, Lee was shocked by the startling news that the entire Army of the Potomac was already on the march through northern Maryland, after having crossed the Potomac on June 25-26. Not anticipating such alacrity, the news struck Lee like a body-blow, after hearing nothing about the Union Army’s whereabouts for nearly a week. With much of his own army situated around Chambersburg, and with his most advanced infantry, the Second Corps, headed toward Harrisburg, Lee now knew that the Army of the Potomac was already in close proximity.97

At this time he also heard news that Hooker had been displaced from command of the Army of the Potomac by the former commander of its Fifth Corps, George Gordon Meade. Lee was largely pleased by Meade’s ascension, even if he felt mystified by the continued fickleness of Federal authorities. A new general would need time to get his army in hand, even as Hooker had showed great acumen in some respects, and after Chancellorsville would doubtless have been out for revenge. Nevertheless, by now the non-descript Meade was known to former West Pointers on both sides as a formidable, careful fighter.

While Meade proceeded to familiarize himself with the entire Union army’s whereabouts (he adopted Hooker’s chief of staff, Dan Butterfield for this purpose), he continued to press Northern units onward. This rapid pursuit was surprising because Lee’s Army had kept up a swift pace in surging north during this grueling campaign, which had taken a toll on Barksdale’s ranks. Private Nash described the difficult trek in a June 23 letter: “We have done some hard marching since we left Fredericksburg. Our men suffered with heat as hot as we would be in Miss [and] I believe I never felt warmer weather. Many of the men were completely overcome with heat. Some fainted by the road. I was suddenly attack [by sunstroke] and fainted away for some time.”98 Not only was Lee’s Army exhausted but also strewn out for miles along dusty Pennsylvania roads by the time the Union Army’s whereabouts became known.

On June 28, after being informed of the danger, Lee dispatched fastriding couriers to his far-flung commands with orders to concentrate to meet the Army of the Potomac. Thanks to finally having gained timely intelligence, a greatly relieved Lee told his top subordinates on June 29, “Tomorrow gentleman, we will not move to Harrisburg, as we expected, but will go over to Gettysburg and see what General Meade is after.”99 But former attorney Colonel Eppa Hunton, who commanded the Eighth Virginia Infantry of General George Edward Pickett’s Division, who was destined to fall wounded in “Pickett’s Charge,” described Lee’s true thinking: “the invasion of Pennsylvania would be a great success, and if so, it would end the war … .”100

On the same day that Harrison reached the army, the confidence of Barksdale’s men for success continued to soar like the rising temperatures. On this day, Private Nash described in a letter to his wife Mollie how, “we are in the enemies country, and so far [it] has amply paid for the invasion. We are all liveing [sic] on the fate of the land [and] There is the finest wheat, now nearly ripe [and this is] the richest and most beautiful country I ever beheld [and] I hate to see such a fine country in the possession of such people.”101

A mighty clash of arms among the sprawling farmlands of south Pennsylvania was now inevitable. Instead of retiring west of the mountains to concentrate his forces, Lee decided to gather his troops on the east side, where the Army of the Potomac was rapidly pushing north. A climactic meeting of two armies now moving toward each other was only a matter of time. Like many great battles which have determined the course of history, however, the Battle of Gettysburg was about to result from an accidental clash of arms. Two great armies were about to unexpectedly collide just northwest of Gettysburg on the hot morning of July 1 in what became the largest battle on the North American continent.

Contrary to one of the most persistent myths about Gettysburg, the battle was not the result of barefoot Southern troops desiring to secure shoes rumored to be stored in the town. Both armies were drawn to Gettysburg because it was a vital crossroads center, where nearly a dozen roads met from all points of the compass. With the dusty roads of Gettysburg radiating outward like the spokes of a wheel and acting like a giant magnet to the interlopers in blue and gray, it was as if fate itself was drawing the two armies together to decide America’s future once and for all.102

Abraham Lincoln, for one, placed great faith in Meade, a competent and capable, if not brilliant, West Pointer (class of 1835) of Scots-Irish stock, who now commanded the Army of the Potomac. At age fortyseven and a Mexican War veteran, he presented the government no such problems as Hooker had, and would simply fight hard per his duty. “I think a great deal of that fine fellow Meade,” proclaimed Lincoln with typical understatement.103 Robert E. Lee’s comment was: “General Meade will commit no blunder in my front.”104 However, the unassuming Meade now faced the greatest challenge of any American army commander since George Washington at Trenton in late December 1776: defeating an army, Lee’s, that had never yet been beaten. And now he would have to meet it, not on ground carefully chosen by himself, but in the open terrain of Pennsylvania.

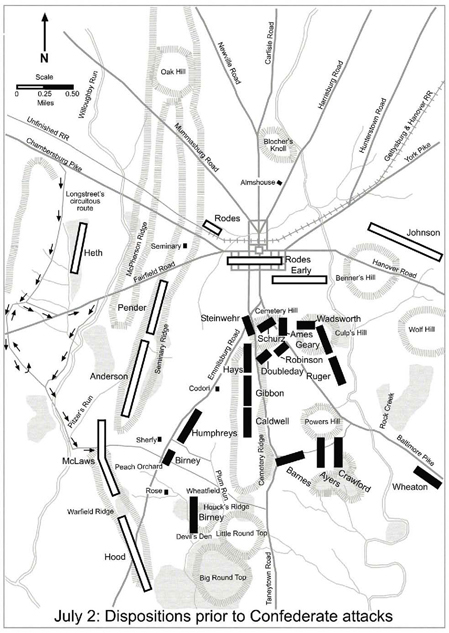

On the morning of July 1, approaching Gettysburg from the northwest and initially believing that they were facing only ragtag Pennsylvania militia, Harry Heth’s Division of A.P. Hill’s Third Corps smashed into two brigades of General John Buford’s Union cavalry. A fast-escalating battle, with dismounted, veteran troopers in blue blasting away with fastfiring breech-loading carbines, quickly developed. The dismounted cavalrymen held Heth off long enough to stop his line of march and force him into battle lines. Thereupon John Reynolds’ First Corps of the Army of the Potomac, including the renowned “Iron Brigade,” arrived. Taking on a life of its own, the fighting soon spun out of control, Heth’s reconnaissance turning into a major battle. Pender’s Division was right behind Heth’s, but the Union Eleventh Corps was right behind Reynolds. Lee was yet unready for a major engagement, not only because of the lack of intelligence from Stuart but also because Longstreet’s powerful First Corps was still to the west and Ewell’s Second Corps was to the north. But the showdown at an obscure college town in south central Pennsylvania, where all roads seemingly led, was already underway.

Fighting raged across the brightly colored fields, rolling hills, and woodlands northwest of Gettysburg. This was Lee’s unwanted battle at a place and time not of his choosing. Worst of all, Lee was unable to ascertain if he faced the entire Army of the Potomac or only an advanced portion. However, the situation suddenly changed when two divisions of Ewell’s Corps arrived from the north, striking the ill-fated Eleventh Corps, which had previously been mauled by Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville. Robert Rodes’ initial attack was clumsy and its first onset was shredded; but then Jubal Early’s division arrived and the entire Federal right flank caved in.

Together with Pender supporting Heth against the already battered First Corp, whose commander, Reynolds, had been killed, the entire Union line broke in a mad scramble to retreat through the town, thence to the formidable heights south of it. The Confederates captured upwards of 3,000 prisoners, “the number being so great as to really embarrass us,” according to Early, and the Confederates thence held both the field of battle and Gettysburg itself.

The only problem was that the Federals retreated to better terrain south of the town than they had had tried to hold west and north of it. And they had kept behind part of a division plus artillery to secure it for such a contingency. The beaten Federals rallied on the position, even as a stream of reinforcements arrived. Among these the most important was Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, head of the Second Corps, who quickly took charge of the situation. The Federal line was now emplaced on the high ground of Cemetery Hill, south of Gettysburg, and heavily timbered Culp’s Hill, to its right. Both elevations were located at the northern end of Cemetery Ridge, which extended south for nearly a mile and a half till ending in more formidable heights called Little Round Top and Round Top. General Lee, immediately recognizing the importance of securing Cemetery Hill, ordered Ewell to take the high ground, “if practicable,” and if he could so “without bringing on a general engagement.”

This has become one of the most controversial orders of the war, with partisans of the late, lamented Stonewall claiming that of course those hills would have been taken, with the Yankees on the run, if “Old Jack” had still been alive. However, Ewell, new to corps command, did not feel that he could organize a proper assault. Aside from one of his brigadiers, John B. Gordon, who had his fire up, he could not see how Rodes’ Division, which had just suffered 3,000 casualties, or Early’s, which due to new intelligence or rumors (another consequence of the absence of Stuart’s cavalry) had to dispatch two brigades backward to watch other roads. He had no connection at all with A.P. Hill’s command to his right, which had been fighting all day and was bloodied enough. And his own third division, under Edward Johnson, had yet to come up. Meantime his own units were strung out and disorganizaed, as were Hill’s, while all he could see was a frowning array of artillery and infantry on the Union-held heights as the daylight slipped away.

In Gettysburg literature, Ewell has been chastised for his hestitation to take those heights ever since that day, but he received no firm order to do so, and his main support since has come from Federal officers such as Henry Hunt, who said, “Ewell would not have been justified in attacking without the positive orders of Lee, who was present, and wisely abstained from giving them.” But the final verdict must go to Hancock, who said that if the Confederates could have rushed the heights in the initial hour when the First and Eleventh Corps broke, they might have been taken. But after that slim hour an attack would have been repelled with loss. Of course the Federals were initially disorganized after their retreat, but so were the Confederates after their victory, which was a typical factor in all Civil War battles. Ewell would have thrown away the July 1 victory if he had been repulsed while pushing it too far in the twilight, having no artillery of his own in position to bear against the hills, but sending his men into the face of a considerable Federal array. This is even as Hancock called the fallback Union stronghold “the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle I ever saw …”105

Lee won the first day at Gettysburg. In fact, he had already gotten a good start on his prediction to Trimble of smashing the lead elements of the Federal army. But now he had to think of something else, quickly. The battle was upon him, whether he wanted it at this time or not, but the Union troops were steadily being reinforced upon their newfound heights, and it was now his task to concentrate the full Army of Northern Virginia in a race for numerical advantage.

That evening, amid a cloud of dust, the reinforcing Union Twelfth Corps arrived to take good defensive positions on the 140-foot high Culp’s Hill. Ewell’s third division, under Johnson, arrived, weary from their much longer march. The Union Third Corps was coming onto the field, soon to be followed by the Second Corps, while Anderson’s Division of Hill’s Corps came up, and Longstreet’s Corps was on the way.

That night, a flurry of conferences took place among the Confederate high command, to determine how to hit the Federals next. Longstreet, for one, was appalled that Lee wanted to resume the offensive at all against that position. Though a hard-hitting attacker, he preferred the tactical defensive, and thought he had come to an understanding with Lee before the invasion began that the Confederates would only maneuver to invite offensive tactics, not initiate them. Meantime, the Federal troops on their heights could be easily outflanked by a further maneuver, interposing Lee’s army between Meade’s and Washington. Lee would hear none of it, however, only saying, “The enemy is here, and if we do not whip him, he will whip us.”

The Confederates would resume the attack the next day, and to Longstreet’s chagrin, he learned that it was his own corps that would have to strike the major blow. The heights faced by Ewell’s corps having finally been determined to be “impracticable,” the solution was to have Longstreet’s fresh troops bypass them to assault the lower ground on the Union left along Cemetery Ridge.

Another great controversy about Gettysburg has arisen over whether Longstreet was ordered to attack “at dawn,” or first thing in the morning, or, as Lee might have put it, “as early as practicable.” There can really be no doubt that sometime on the evening of July 1 Lee urged an attack as early as possible the next day. To this many acolytes of Lee have attested, largely for the purpose of putting blame for the next day’s battle on Longstreet. However, in the absence of Stuart’s cavalry, Confederate reconnaissance was pitifully poor. Longstreet was given no guides, or else faulty ones. It was not clear until the last moment where to put his men in position, and Lee’s orders, “to attack up the Emmitsburg Road,” displayed a complete misunderstanding of the battlefield.

It is possible, too, as many writers have claimed, that Longstreet took a “passive-aggressive” attitude toward the impending assault, not fully wishing to comply with Lee’s orders, but only grudgingly doing so, and with no great speed or initiative of his own. But this hardly equates with the loyalty he must have felt to his own men, and when he finally did assault the Federal left, it was with full force and determination to succeed. And among his brigadiers were such as William Barksdale, who wanted nothing more than to end the war in one afternoon, with the greatest victory yet for Confederate arms.

The symbolically red dawn of July 2 consequently witnessed the beginning of “the most critical day at Gettysburg.”106 Shaking off their weariness, Barksdale’s troops were up early in the predawn darkness of July 2. Even the blackness of 4:00 AM, when they rose, felt like a sultry, summer morning along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. They were yet sore and tired. Barksdale’s men had force marched at a brisk pace from Greenwood, east of Chambersburg and around fifteen miles from Gettysburg, until halting around midnight on July 1 and encamping on Marsh Creek, several miles west of town. With muskets on shoulders, they now headed toward Gettysburg, a rendezvous with destiny, and the grim killing fields of summer.107

The dramatic confrontation at Gettysburg continued unabated on July 2 between Generals Meade, the homespun “tall, spare man,” and Lee, the handsome, dignified Virginian, whose fighting blood was up after tasting success on July 1. While Meade was initially reluctant to accept the Confederate challenge to stake everything on a final showdown at Gettysburg, Lee felt quite the opposite. He wanted to strike a decisive blow before Meade could gather all his troops, sensing a great opportunity.

Despite its setback and heavy losses on July 1, however, the Army of the Potomac was anything but defeated. In a strange way, so many past defeats now worked as a tonic on the overall psyche of Meade’s Army, having been tempered by adversity. No sense of panic or demoralization infiltrated this increasingly resilient army now fighting on its home soil. In the analysis of an observant Union officer, Captain Frank Aretas Haskell, “the Rebel had his whole force assembled, he was flushed with recent victory, was arrogant in his career of unopposed invasion, at a favorable season of the year … but the Army of the Potomac was no band of school-girls. They were not the men likely to be crushed or utterly discouraged by any new circumstances in which they might find themselves placed.”108 And this reality was never more true than on the second day of Gettysburg.

But Lee was determined to exploit the first day’s success to the fullest, and so far, with eight of his nine divisions on or near the field, was winning the race for the build-up. He decided to resume the offensive to crush Meade’s Army on the morning of July 2, before it was united and in position.109

But the glory days of Lee’s easily vanquishing one incompetent Union general after another were no more. In a letter that was right on target, Captain Haskell described the general feeling throughout the army in regard to Meade’s appointment on June 28, “The Providence of God had been with us … I now felt that we had a clear-headed, honest soldier, to command the army, who would do his best always—that there would be no repetition of Chancellorsville.”110 Most important, the Army of the Potomac was emboldened by the fact that Meade had decided on the night of July 1 “to assemble the whole army before Gettysburg, and offer the enemy battle there.”111

As the early morning mists of July 2 rose higher from the low-lying areas around Gettysburg, thousands of Meade’s veterans no longer fretted about what the brilliant Lee was going to do next. A quiet confidence dominated the ranks of blue. As Captain Haskell penned, “The morning was thick and sultry, the sky overcast with low vapory clouds [and] all was astir upon the crests near Cemetery, and the work of preparation was speedily going on.”112

Therefore Lee’s decision to rely upon the tactical offensive to push Meade off his high ground perch was sure to meet with stiff resistance, upon confronting highly-motivated veterans in defending home soil.113 As revealed in a letter when a South Carolina officer quoted the words of a boastful Yankee prisoner, the Confederates would find that there was “a great difference between invading the North & defending the South.”114

From the beginning, seemingly nothing went right for either Lee or his army on July 2. The Confederates were still without Stuart, and Meade was allowed all morning to prepare to meet Lee’s assault and for his troops to arrive on the field. Barksdale’s men, up since dawn, marched along the Chambersburg Road, moving east toward Gettysburg through the rising dust. While Lee planned to unleash an oblique attack with John Bell Hood’s and Lafayette McLaws’ Divisions, Longstreet’s Corps, to roll up Meade’s left flank to exploit the first day’s gains, his top lieutenant, Longstreet, thought quite differently. He wanted to ease around the southern end of the Union Army’s defensive line to outflank the Cemetery Ridge position.115

As day went on, nothing happened quickly for the Confederates. Longstreet failed to immediately march south to a position on Meade’s left flank as early as Lee had anticipated. Instead hour after hour, he waited—a most “impractical decision”—for a single Alabama brigade (General Evander Law’s) to come up before undertaking his flank march south, as if time was of no importance or Law couldn’t have caught up to the corps by himself. In consequence, Lee’s proposed attack led by Longstreet’s two divisions was not launched in the morning as desired by the commander-in-chief. That morning, too, the Union Fifth Corps arrived as well as remaining brigades of the Third Corps.

Meanwhile, Barksdale’s troops swiftly marched across McPherson’s Ridge past the sickening clumps of bodies left from the previous day’s fighting. They arrived on Seminary Ridge near Lee’s headquarters, where the Chambersburg Pike gained Seminary Ridge, around 9:00 AM. Longstreet’s more than 14,000 battle-hardened veterans were tardy in moving out when timeliness was vital for success. Here, the Mississippians, footsore and tired, at least gained a few hours of much-needed rest with the lengthy delay.

Finally, around noon, Longstreet embarked upon his much belated march south to gain an attack position beyond the Union Army’s left flank. Longstreet was to deliver the knock-out blow from Lee’s far right. To keep Meade distracted, A.P. Hill’s Third Corps would apply pressure to Meade’s center to keep Union forces there in place. And Ewell’s Second Corps would demonstrate on the north before Culp’s Hill and launch a full assault if a favorable opportunity presented itself.116

After numerous delays and counter-marching in an attempt to disguise his movement from Yankee eyes, Longstreet’s Corps finally reached its designated position in mid-afternoon. With the rest of McLaws’ Division, Barksdale’s soldiers, dusty, hot, and sweaty, reached their assigned position to the left of Hood’s Division. Because Barksdale had brought up McLaws’ rear, the Mississippi Brigade fell into line on the left flank of McLaws’ Division just north of Joseph B. Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade, after pushing up fairly steep, ascending ground along the heavily timbered western slope of Seminary Ridge. Here Barksdale positioned his troops along Seminary Ridge in the cooling shade, but inadequate shelter, of Emanuel Pitzer’s Woods around 3:00 PM. Cadmus “Old Billy Fixin” Wilcox’s Alabama brigade, General Richard Anderson’s Division, Hill’s Third Corps, was on Barksdale’s left.

By now on this scorching mid-afternoon, Confederate battle-plans were in the process of slowly self-destructing and falling apart at the seams. Longstreet’s time-consuming flank march, and then countermarch (to escape detection), south to form on Lee’s far right had cost far too much time. The additional hours—a reprieve of sorts—allowed Meade’s Army the opportunity to establish its “operational balance,” gather strength, and prepare for the upcoming attack. By now the last of its corps, the Sixth under John Sedgwick, was nearing the field.

Instead of obtaining an advantageous position beyond the Union army’s left and finding no enemy before them as anticipated when Lee’s plans were first formulated, McLaws and his officers were shocked to discover a good many Yankees ready for action on either side of a Peach Orchard barely 600 yards distant. Lee’s overall tactical objective was to gain the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, nestled about halfway between Seminary and Cemetery Ridges, and attack up the Emmitsburg Road to roll up Meade’s weak left flank. But everything had changed by the mid-afternoon of July 2. Instead, the formidable might of the entire Third Corps was now poised on either side of the high ground of the Peach Orchard beside the Emmitsburg Road, blocking the way to Gettysburg to the northeast. With a lengthy defense line pivoting on a salient angle, nearly 11,000 Yankees of General Daniel Egar Sickles’ Corps were deployed along the Wheatfield Road and toward Little Round Top, and then north along the Emmitsburg Road that led to Gettysburg. The 45-degree, defensive angle’s point existed where the two roads intersected on the Emmitsburg Road Ridge at the Peach Orchard of farmer Joseph Sherfy.

No one was more upset by this startling new development of thousands of alert Yankees now occupying the high ground of the Peach Orchard than Lafayette McLaws and his fellow division commander on the Confederate right, John Bell Hood. They now saw the Peach Orchard overflowing with Union troops and batteries, in a lengthy blue line extending all the way to Little Round Top, where Union signalmen were busy betraying Confederate movements. An incensed McLaws blamed Longstreet “for not reconnoitering the ground.” Clearly, in regard to ascertaining the new position of an entire Union corps, Confederate leadership, staff work, intelligence-gathering, and reconnaissance had failed miserably.

Now poised on Seminary Ridge, McLaws’ troops realized that they were simply not in a position from which to strike Meade’s supposed vulnerable left flank. As Colonel Humphreys, commanding the 21st Mississippi, described this most perplexing tactical situation in a letter, after realizing that Lee’s plan to gain General Meade’s left was already checkmated: “When we arrived there it was unmistakably anything but the flank [and] it was a formidable compact line of frowning artillery and bristling bayonets.”117 Fueling his anger toward his corps commander’s leadership failure, McLaws never forgot the shocking sight presented to him by the Peach Orchard position: “The view presented astonished me.”118 And Colonel Edward Alexander Porter lamented how if Longstreet’s “corps had made its attack even two or three hours sooner than it did, our chances for success would have been immensely increased.119

In addition, a confident Major General Alfred Pleasonton, commander of the army’s cavalry corps, reasoned that by this time, “We had more troops in position than Lee.”120 Therefore, in many ways, Barksdale’s Mississippians shortly would be fighting against a cruel fate today because the odds, more than 10,000 Yankees poised around the Peach Orchard and supported by plenty of artillery manned by veteran cannoneers, were stacked high against them. Clearly, the Magnolia State solders would have to struggle long and hard against the odds to compensate for the many mistakes and miscalculations by the Confederate leadership.

About all that Barksdale’s soldiers now knew was that a little Peach Orchard stood atop a slight knoll—its high point stood at the intersection adjacent to the Wheatfield Road and only a few yards east of the Emmitsburg Road—amid a gently rolling landscape of open fields that lay before them. And, most of all, they realized that a good many Union troops and rows of cannon were aligned across the commanding ground, patiently awaiting their next move. Nevertheless, a can-do spirit yet remained high among Barksdale’s veterans. Private Dinkins, 18th Mississippi, believed that the infantry assaults of “General Lee’s army [were] irresistible [and] no troops on earth, with the arms then in use, could have withstood his charges.”121 At the edge of a thin belt of woodland just west of Seminary Ridge and under the relative protection of a reserve slope position, one soldier described how the 13th Mississippi troops were first “formed … under a ledge of rocks along a small branch [and in] enough hill and timber to hide us from the Yankees.”122

Gettysburg’s First Day had already brought victory, and Lee’s Rebels expected that the next day would be no different. Hence, Lee’s soldiers felt that this small town of Gettysburg might soon become the site of the most decisive Southern victory of the war. Sir Arthur James Lyon-Fremantle, an astute officer of His Majesty’s Coldstream Guards, sensed traces of smugness in the Confederate ranks, however. Having only recently run the Union naval blockade to reach the South in order to observe Lee’s Army, he noted its air of overconfidence, writing how, “The universal feeling in the army was one of profound contempt for an enemy they had beaten so constantly, and under so many disadvantages.”123

Meanwhile, the sight of the Peach Orchard’s high ground covered with the Third Corps’ blue formations and rows of cannon was imposing. In addition, behind the Peach Orchard position to the east loomed Cemetery Ridge, which was distinguished by its tree-line on the distant horizon. Ironically, the Mississippi Brigade’s last great attack was at Malvern Hill almost one year to the day. And now Barksdale’s soldiers would have to do it all over again in attacking the formidable Peach Orchard sector. Hardly could Barksdale’s veterans now realize that the upcoming attack on the Peach Orchard and Cemetery Ridge would far surpass the blood-letting of Malvern Hill. As Colonel Humphreys lamented in a letter, “many Mississippians perished” at Gettysburg and more so than on any other field of strife.124

As often before an offensive effort, some of Barksdale’s troops tore up their letters from loved ones. If killed during the upcoming assault, then these Mississippi soldiers wanted no victorious Yankees to read, ridicule, or poke fun at his family members’ written words, thoughts, and emotions. This was a nagging concern because they themselves had often found ample amusement in reading letters removed from Union dead.125 Partly from necessity, Barksdale’s veterans had long taken almost everything from Federal dead. After the slaughter of hundreds of bluecoats at Fredericksburg, a Virginia artilleryman, Henry Robinson Berkeley, wrote with some amazement in his diary how, “All the Yankee dead had been stripped of every rag of their clothing and looked like hogs which had been cleaned.”126 In a letter to his beloved sister Anne, Adjutant Oscar Ewing Stuart, 18th Mississippi, bragged of the spoils of war taken from Union dead, “I have a fine Yankee canteen, but could not get an overcoat.”127 Durng the march to Gettysburg, Lieutenant Colonel Fremantle, the keen-eyed British observer, wrote with some amazement how “the knapsacks of the [Mississippi] men still bear the names of the Massachusetts, Vermont, New Jersey, or other regiments to which they originally belonged.”

On this scorching afternoon in Adams County, the formidable challenge of capturing the Third Corps’ high ground position at the Peach Orchard, looming before the Mississippians in forbidding fashion, did nothing to sway their determination to win today at any cost. Private Dinkins, 18th Mississippi, described the typical psychology of the brigade’s soldiers: “One would not suppose that in so short a time after they had fought with such desperation, and seen so many of their friends killed and wounded by their sides, men could be cheerful and hopeful, could throw off trouble, or face dangers, as occasion demanded. Merry laughter and jests could be heard at every mess fire. The men sang and danced at night, and talked of home … it was impossible to break or even check their spirits.”128

Despite about to launch yet another offensive effort, the spirits among the Magnolia State soldiers remained surprisingly high this afternoon. During the long march from Virginia to this vast killing field nestled between Seminary and Cemetery Ridges, the Mississippi Rebels had sung their favorite songs as if carefree schoolboys on a lark, and perhaps some soldiers whistled or sang these tunes to now break the mounting tension. These popular tunes included old “plantation songs,” and those of African-American origin, such as “I’m Gwying down the Newburg Road,” “Rock the Cradle, Julie,” and “Sallie, Get Your Hoe Cake Done.”129

British Colonel Fremantle was greatly impressed by the Mississippi Rebels, having witnessed them on the march to Gettysburg: “Barksdale’s Mississippians, renowned for their heroic stand at Fredericksburg, were passing—marching in a particular lively manner—the rain and mud seemed to have produced no effect whatever on their spirits. They had got hold of colored prints of Mr. Lincoln, which they were passing about from Company to Company with many remarks upon the personal beauty of Uncle Abe. One female had seen fit to adorn her ample bosom with a huge Yankee Flag, and she stood at the door of her house, her countenance expressing the greatest contempt for the bare-footed Rebs; several companies passed her without taking notice, but at length a Mississippi soldier pointing his finger, and in a loud voice, remarked, ’Take care, madam, for we Mississippi boys are great at storming breastworks when the Yankee colors is on them.’ After this speech the patriotic lady beat a precipitate retreat.” While spirits were high, Barksdale’s men looked unlike crack troops and anything but ready for the formidable challenge which lay ahead. They were dust-covered, ragged, lice-ridden, and dirty. The Mississippi Rebels now appeared more like scarecrows in a Magnolia cornfield along the Tallahatchie than some of the army’s elite combat troops.130

Private Dinkins described his tattered uniform as consisting of only “the rim of a hat, no top or brim to it, simply a band; the waist of an old coat (the shirt had been cut off to patch the sleeves, and for other uses); a pair of old Yankee pants, the left leg split from the knee down, and tied together with willow bark … mangy skin, and, what was worse than all, [I] was full of ’gray backs’ [body lice and] a pair of boots, which [were] tied together at both ends and cut a hole in the middle; there were shoes [and] no socks.”131 One of Lee’s men wrote how the army consisted of “two years’ veterans [who] were scarcely recognizable by their own mothers as the tidy boys who had ‘gone out for glory,’ in resplendent uniforms,” which were no more.132

One Confederate officer described the shocking appearance of Lee’s veterans, who looked like a strange aberration of abject poverty amid the bountiful countryside of south central Pennsylvania: “Begrimed as we were from head to foot with the impalpable gray powder which rose in dense columns from the macadamized pikes and settled in sheets on men [we] had no time for brushing uniforms or washing the disfiguring dust from faces, hair, or beard [and] all of these were of the same hideous hue.”133

In jaunty fashion and with a cockiness that betrayed their lethal prowess on the battlefield, some Mississippi veterans wore bucktails in dirty slouch hats or gray kepis. These “trophies” were taken from the dead of the famous “Bucktails,” of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves. In the beginning, these Keystone State frontiersmen had been instructed by officers to bring the trophy of a white-tailed deer tail to verify their marksmanship. At Gettysburg, the prestige of these trophies now worn by Barksdale’s veterans instead verified the deadliness of Mississippi marksmanship. Giving them a devil-may-care look, the Mississippians, wearing the deer tails from Pennsylvania’s mountains, displayed these badges of honor with a great deal of pride.134

But nothing else distinguished the Mississippians’ appearance except for a shabby, lean, and threadbare look that masked a plethora of superior combat qualities. Clearly, Barksdale’s men looked like the antithesis of elite soldiers. Jimmie Dinkins described himself as a “Little Confederate” with “long yellow hair, badly tangled and matted,” and badly in need of a good bath and thorough delousing.135

Twenty-five-year-old Private Robert A. Moore, Company G, 17th Mississippi, was determined to win decisive victory at any cost “even life itself, for the liberty of our country.” Like other Confederate Guards members, Private Moore believed that he was “battling for our rights & are determined to have them or die in the attempt.” However, Private Moore, from a slave-owning family on a farm nestled amid the rolling hills immediately north of Holly Springs, was fated to “die in the attempt.” He would survive Gettysburg, but fall to Yankee bullets at Chickamauga, less than three months later.

In his diary, Private Moore wrote with pride how he and his comrades were “determined to fight as long as their country demands.” This crusading zeal among Barksdale’s veterans was not fueled as much by a mindless support of slavery—since most of these Mississippi soldiers owned none—as it was in fighting to defend their young republic in a righteous struggle against a “ruthless invader who is seeking to reduce us to abject slavery,” explained Private Moore. Dark-featured and handsome, the never-say-die 17th Mississippi private also scribbled in his diary that they must “let our last entrenchments be our graves before we will be conquered” by the Yankees. For Private Moore and other Mississippi soldiers, this was most of all a holy struggle “for the liberty of our country” like their Revolutionary War forefathers.

Yet another motivation was all-important in explaining why the Mississippi Brigade’s soldiers would perform so well at Gettysburg: Grant’s invasion of their home state. In his diary on February 5, 1863, an incensed Private Moore, 17th Mississippi, penned how “heard from home this evening [and the invading] abolitionists have left Pa an old blind mule,” while taking practically everything else from his family’s middleclass Mississippi farm. During the spring of 1863, Grant’s western army slashed across Mississippi in a bold campaign to reduce fortress Vicksburg. A gloomy Private Moore scribbled in his diary on May 18 how, after Grant won the battles of Port Gibson and Raymond, Mississippi, “the enemy have occupied Jackson, the capitol of the State.” And only four days later, he wrote in his diary how, “to-day was recommended as a day of prayer by our chaplain for our nation & particularly our native state which is now invaded by our ungenerous foe.” In a letter to his wife that revealed the ironic and paradoxical situation of the Mississippi Brigade at this time, Private Nimrod Newton Nash, who was known as “Old Newt” to the boys in the 13th Mississippi, explained the burning desire of so many of Barksdale’s men at this time: “I wish Gen. Longstreet’s Corps was down there, and they would let us loose on old Grant. We would have him out of his den in a little time.”136 But while Barksdale’s soldiers, racked by anxiety and gloomy thoughts about the welfare of their families, had marched with confidence toward Gettysburg, they eagerly awaited the news of the fate of their home state and Vicksburg, the key to the Mississippi River.

And the Mississippi Brigade’s top leaders were likewise deeply affected by the fates of homes, families, and relatives in the Magnolia State, and these nagging concerns were on their minds on the field of Gettysburg. After crossing the Mississippi from eastern Louisiana in the greatest amphibious operation to date, Grant’s Army had swarmed into Colonel Humphreys’ own Claiborne County on May 1. Humphreys’ sister, Mrs. A.K. Shaifer whose husband served in the Port Hudson, Louisiana, garrison, on the Mississippi below Vicksburg, had been driven from her home, when the battle of Port Gibson literally erupted on her property. The Humphreys’ family plantation “Hermitage” was caught in the vortex of Grant’s storm. Clearly, this increasingly brutal war now affected Barksdale, Humphreys and their men in the most personal of ways: a factor partly explaining why the Mississippi Delta colonel and his 21st Mississippi were so highly motivated and determined to reap a decisive victory at Gettysburg.137 Reflecting the July 2 mood in the ranks, an anguished 13th Mississippi private scribbled in a letter how, “we have all been in an agony of suspence [sic] to hear of the final result of the conflict which has been going on in Miss.”138

Many of the 1,620 veterans of Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade now massed in Pitzer’s Woods sensed the ironic twist fate that now placed them before the Peach Orchard. By the time of the showdown at Gettysburg, Lee’s Army contained more Mississippi infantry regiments than defended Vicksburg. With most of Mississippi’s sons fighting and dying far away, Vicksburg was doomed. Instead of defending their home state, the four regiments of Barksdale’s Mississippi and Lee’s other seven Mississippi infantry regiments hoped to secure victory at Gettysburg to relieve their beleaguered homeland. While Vicksburg was slowly strangled to death, Lee’s Mississippi troops were now farther away from the Magnolia State than ever before.139 With his thoughts never far from his invaded homeland, Private Nash, 13th Mississippi, penned in a letter home, “I feel story for our boys at Vicksburg.” But the worst was yet to come.140

Of all Longstreet’s troops, the Mississippi Brigade now most directly confronted head-on the full might of the Peach Orchard position, bristling with artillery and thousands of veterans in blue coats. But this formidable appearance of Third Corps might disguised weaknesses. Quite simply, too few Union fighting men were deployed along a long, over-extended front, offering “great dangers,” in the words of one tactically astute Union general. However, negating this advantage, what also lay before Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade was a natural killing field that flowed east across the open fields and gently rolling terrain that ascended up to the Emmitsburg Road. The Mississippi Brigade’s opportunity to strike the most vulnerable point—the salient angle—in the Third Corps’ line had developed quite unexpectedly, and to Meade’s utter shock back at his Cemetery Ridge headquarters.

In a letter, Captain Haskell described what had set the tactical stage for the struggle for possession of the Peach Orchard, when the Third Corps’ independent-minded commander General Daniel Egar Sickles “Somewhat after one o’clock P. M. [made] a movement to the second ridge West, the distance is about 1,000 yards, and there the Emmitsburg road runs near the crest of the ridge … Gen. Sickles commenced to advance his whole Corps, from the general line [on Cemetery Ridge], straight to the front, with a view to occupy this second ridge, along, and near the road. What purpose could have been is past conjecture [but] It was not ordered by Gen. Meade, as I heard him say, and he disapproved of it as soon as it was made known to him.”141

Incredibly, because he deemed his assigned line “unsatisfactory,” Sickles had moved his entire corps of two divisions forward to the west against orders. The Third Corps had been initially ordered by Meade to take a defensive position on the Second Corps’ left and to extend the Union line down Cemetery Ridge southward to Little Round Top on the morning of July 2. All of a sudden, therefore, the Peach Orchard position now presented Lee with an unexpected development and a new opportunity. He now found his Third Corps opponent in an entirely new position that disrupted his original battle-plan of assaulting up the Emmitsburg Road to hit the Union left flank. To exploit Sickles’ ill-advised forward thrust that created an over-extended, vulnerable salient, without support on either side, Longstreet now possessed an opportunity to crush the Third Corps with a mighty offensive onslaught.

Indeed, the Peach Orchard salient, a 45-degree angle formed by defensive line that spanned northeast along the Emmitsburg Road and southeast along the Wheatfield Road, was now vulnerable on three sides, hanging in mid-air before Meade’s main line aligned along Cemetery Ridge. A perplexed Captain Haskell lamented how Sickles “supposed he was doing for the best; but he was neither born nor bred a soldier [and] we can scarcely tell what may have been the motives of such a man—a politician [and] a man after show and notoriety.”142

However, a nervous Sickles had only abruptly responded to a vexing tactical situation and the contours of geography at Cemetery Ridge’s southern end, where the ridge gradually dipped as it extended south to flatten out to reach a low point, just north of Little Round Top. He had been assigned the worst ground on all of Cemetery Ridge, low, marshy, and in his view dominated by the elevated ground at the Peach Orchard in his front. By occupying that height he would be better able to stave off an attack; just as important, he believed the Confederates could pulverize his position on Cemetery Ridge if they occupied it themselves.

Even General Henry Hunt, commanding the army’s artillery, recognized the Peach Orchard’s high ground as “favorable” for defense, especially artillery placement. Captain George E. Randolph, commanding the Third Corps’ Artillery Brigade, felt the same. Recalling how Confederate artillery perched atop the higher ground of Hazel Grove had severely punished his low-lying troops at Chancellorsville, Sickles had immediately viewed the higher ground along the Emmitsburg Road as well worth occupying, if only to deny its possession to Lee.143 Coinciding with the views of his top lieutenant, General David Bell Birney, whose First Division held the Peach Orchard salient, Sickles was convinced that “to abandon the Emmitsburg road to the enemy would be unpardonable.”144

Sickles, a leading New York City Democrat and self-promoting politician of the cut-throat Tammany Hall machine, possessed lofty White House ambitions. As suspected by Union officers who were familiar with the unorthodox, “notorious” New Yorker, the ever-ambitious Sickles knew that winning lasting fame at Gettysburg was a sure ticket to the White House.145 Therefore, leading Union officers, including Meade, suspected that Sickles’ decision to secure that Peach Orchard defensive line was more “political than military.”146

However, it was also true that Sickles, at Chancellorsville less than two months earlier, had witnessed Stonewall Jackson’s famous flank attack while it was in motion, but had misinterpreted its meaning. He assumed it was a retreat rather than preparation for the most devastating surprise attack of the war, and now at Gettysburg he refused to be caught at a disadvantage, or unawares. As the far left of the Union army he wanted the best defensive ground he could find. In fact, unlike Meade at this time, who expected a Confederate attack against his right, Sickles was fully correct that another Rebel flank attack was in the works, and that it was coming straight against his part of the line.

Captain Haskell thought that “there would be no repetition of Chancellorsville” on July 2.147 But he also added, “This move of the Third Corps was an important one [because] it developed the battle [but] O, if this Corps had kept its strong position upon the crest” of Cemetery Ridge.148 Indeed, the tactically astute Longstreet saw clearly that Sickles’ line at the Peach Orchard “was, in military language, built in the air.”149 In addition, Sickles’ advance to the Peach Orchard sector also left Little Round Top to the southeast more vulnerable, even though the southern arm of his angled line along the Wheatfield Road extended southeast toward that rocky hill.150

Therefore, thanks to Sickles’ move west over the broad open fields to create an exposed bulge, or salient, situated about halfway between Cemetery and Seminary Ridge, and his attempt to hold the Peach Orchard salient and Emmitsburg Road Ridge with too few troops, the Mississippi Brigade was now presented with the golden opportunity to smash the exposed Third Corps salient and to “end the war in a single afternoon.”151

Gripping their muskets in the relatively cool shade of Pitzer’s Woods, Barksdale’s men marveled at more than the sight of Sickles’ salient.152 Before the Mississippi Brigade’s position in the thick woods, acre after acre of the finely-manicured Joseph and Mary Sherfy farm stretched eastward as far as the eye could see.

One of Lee’s generals was impressed by the richness of this land of plenty, writing how Pennsylvania’s “broad grain-fields, clad in golden garb, were waving their welcome to the reapers and binders [and] on every side, as far as our alert vision could reach, all aspects and conditions conspired to make this fertile and carefully tilled region a panorama both interesting and enchanting.” And Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, commander of Longstreet’s reserve artillery, described how “the Dutch [are] generally apparently very industrious & very prosperous [with] big barns, & fat cattle, & fruits & vegetables were every where.” After all, Pennsylvania’s bounty and prosperity were key factors that had originally caused Lee to decide to invade the Keystone State, where his provision-short army could be re-supplied off what was essentially a vast granary untouched by the war’s wanton destructiveness.153 Private Nash, 13th Mississippi, was amazed by the land’s seemingly endless bounty. He wrote in a letter how there “has been thousands of the finest horses I ever saw taken for the use of the army besides wagons, forage and every other supply for the army.”154 In his diary, Private William Henry Hill, 13th Mississippi, was equally astounded at “their prosperity [and we] have taken a large number of horses, mules … cattle, sheep, forage, &c.”155

But the sheer natural beauty of the landscape lying before the Mississippians like a naturalist’s colorful painting was about to be transformed from a scene of pastoral tranquility into a vast killing field. However, the eerie calm before the storm and dream-like imaginary of the idyllic setting was abruptly shattered when Barksdale shortly screamed out orders to send skirmishers forward to protect the brigade’s front. Each regimental commander hurled his best skirmish company forward from the haven of Pitzer’s Woods into the expansive, sun-baked fields of farmer Sherfy. To safeguard the 17th Mississippi’s front, Colonel Holder ordered Captain Gwin Reynalds Cherry and his Company C soldiers [Quitman Guards] forward into the broad, open fields of summer. A former sergeant major who knew how to get the most out of his men on the battlefield, Cherry was a reliable officer of ability and merit. With a clatter of gear and jingling accouterments, the Pontotoc County boys spilled out of the tree-line and into the open fields bathed in bright sunlight and intense afternoon heat.156

With a lengthy formation of skirmishers from the 63rd Pennsylvania aligned in the open fields before the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the Mississippians were immediately vulnerable when they poured out into the field, where zipping bullets made the air sing. Therefore, experienced skirmish captains ordered their men to take kneeing positions to minimize their vulnerability. However, after retiring closer to the ridge, the blue skirmishers were sufficiently distant that a mounted Longstreet appeared on the skirmish line. Longstreet’s micro-management of even relatively small matters to an extent seldom seen before raised the ire of the proud McLaws, a tough leader, who saw this hands-on leadership as interference and disrespect.157

However, some of Longstreet’s personal interference with McLaws’ Division was well-calculated and beneficial. He ordered Captain Cherry to send two men of Company C, 17th Mississipppi, forward across the sprawling expanse of farmer Joseph Sherfy’s fields to an “unidentified” log house, located before the Emmitsburg Road and the Sherfy House, on a vital mission to “tear down the picket fences which stood around the yard and garden areas,” in the words of Private James W. Duke, Company C, 17th Mississippi.158

Aware of the mission’s extreme danger, Captain Cherry turned to the young orderly sergeant, and ordered him to read off the first two names on the company’s “duty roster.” But no one answered the call. Then, the orderly sergeant moved down the list, and shouted out the next two names. Once again, no man stepped forward from the ranks. Clearly, with the lengthy line of bluecoat Pennsylvania skirmishers, yet blasting away, so near the house, this assignment appeared suicidal. A model soldier, nevertheless, Captain Cherry became incensed by the lack of response. “Angry and exasperated,” therefore, the captain shouted out, “I will make the detail!”159 Even though this assignment was “a job with a limited future” from which any volunteer would very likely never return.160

Knowing that his two best soldiers would not fail to accept the stiff challenge, Captain Cherry made his final decision. He said, “Jim Duke and Woods Mears, they will go.”161 Private Archibald Y. Duke held his breath, while his brother Jim stepped forward without hesitation. Ironically, Archibald, and not Jim, was destined to receive his death stroke on this day; however, clearly, this special mission was most daunting. With a veteran’s insight, Private Duke turned to Woods, and blunted out, “We will be killed.”162

Captain Cherry made his choice not only because these two young men were not only the best Company C soldiers, but also because of their size and strength, which was necessary to tear down the fence line surrounding the house’s garden and yard. Despite knowing that the mission was suicidal and after leaving muskets behind, Privates Duke and Woodson, or “Woods,” B. Mears dashed forward. They then raced through the slight depression amid the open fields about halfway between Seminary Ridge and the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. While heading toward the house, the two Rebels, exposed in the open, expected the 63rd Pennsylvania skirmishers, and even their main line along the ridge to open fire. But then something entirely unexpected and strikingly surreal happened, to the surprise of everyone.

Not a shot was fired at the two young boys in gray when they neared the picket fence around the house’s yard. Almost as if no one had noticed, they had been allowed to race up the open western slope of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. In an act of chivalry, no Federal soldier fired at them from the high ground around the Sherfy House. Although they were breathless by this time, the two Quitman Guards members reached their objective. Here, in frantic haste, they tore down the fence planks, which served an obstacle to Barksdale’s upcoming attack. All the while, the Pennsylvania skirmishers, situated only around “fifty paces” distant, quietly watched the two Rebels’ hectic activity. The Yankees felt a sense of admiration for the daring bravery of the two Company C boys. In honor of their courage, neither the Pennsylvania skirmishers, main line soldiers, or artillerymen fired a shot, allowing Jim Duke and Woods Mears to complete their work.163

Miraculously, the two Mississippi boys returned safely to their comrades without a scratch after completing a dangerous job well done. Hoping to gain insights upon the strength of the Union positions along the Emmitsburg Road, Longstreet quizzed Duke and Mears, asking “What did you see there?” Then, violating military etiquette and protocol, Private Jim Duke posed Longstreet a direct question, “General, do you think we can take those heights?” Knowing that taking the high ground would only come at a frightfully high cost, a bemused “Old Pete” simply replied to the outspoken private, “I don’t know, do you?"164

More than any other Southern unit because it directly faced the Peach Orchard, the Mississippi Brigade was now in the key position to exploit the tactical vulnerability of Sickles’ salient. To bolster his defensive stance on Cemetery Ridge, meanwhile, Meade had strengthened his right around Culp’s Hill at the expense of his left—exactly where Longstreet’s flank attack was about to take place. Hence, by this time, Meade’s left was relatively vulnerable compared to his right.

With a keen eye for choosing good terrain, General Hunt, the capable commander of the Army of the Potomac’s artillery, early realized the potential of the commanding terrain of the Peach Orchard knoll for massed artillery.165 After the overall poor performance of the Union Army’s artillery at Chancellorsville, at no fault of his own since “Fighting Joe” Hooker had made an error of judgment in demoting him, Hunt was determined that the army’s “long arm”—now independent under Meade— would fulfill its potential during what was shaping-up to be the most important battle on the North American continent. After the Union army’s artillery arm had reached its zenith on the open ground at Antietam, Hunt now worked hard to orchestrate a repeat performance on Pennsylvania soil. Most important, he had already ordered Reserve Artillery batteries forth to bolster the Third Corps artillery at the Peach Orchard, strengthening the position based upon his own considerable expertise. Like Meade and fortunately for the Union, the brilliant Hunt was about to have his finest day. Gettysburg marked the high point of Hunt’s career.

Despite the Third Corps’ high ground salient angle jutting out before Meade’s main line along Cemetery Ridge, the elevated position was formidable with its massive array of artillery support from both the Third Corps and the Reserve Artillery, thanks to Hunt’s expert placement of guns. Several Union batteries were “tightly packed” inside the salient angle, and three more were aligned southeast along the Wheatfield Road. More than three dozen artillery pieces were supported by General Charles Kinnaird Graham’s fine Pennsylvania brigade of Birney’s First Division. This battle-hardened Keystone State brigade was poised in good defensive positions at the advanced point of the Peach Orchard salient angle, and all the way northeast along the Emmitsburg Road to the Abraham Trostle Lane. Most daunting, the several veteran Union batteries crammed into the salient angle promised to drop a good many attackers with a vicious fire. A close friend of Sickles, with Tammany Hall connections and a gifted civil engineer, General Graham, age thirty-nine, was the former colonel of the 74th New York Volunteer Infantry, Excelsior Brigade. He now performed as competently on this day of destiny with his brigade as when a tireless dry dock civil engineer of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Supporting the rows of artillery and holding the Emmitsburg Road Ridge sector, Graham’s brigade consisted of half a dozen veteran Pennsylvania regiments. The brigade had launched a successful counterattack at Chancellorsville to help stem the Rebel tide that had reached new heights on one of Lee’s finest days. As fate would have it, this heavy concentration of Third Corps and Reserve Artillery guns and infantry ensured that this would be primarily a Mississippi-Pennsylvania showdown for possession of the vital Peach Orchard. The struggle was guaranteed to be tenacious because the Pennsylvanians now defended their home state. In total, seven batteries (40 guns) of both the Third Corps and the Reserve Artillery, thanks to Hunt’s timely efforts, bolstered the Peach Orchard salient.

The concentrated firepower of these veteran artillery units helped to make up for some of the line’s tactical vulnerabilities, especially filling gaps in a defensive line of infantrymen spread too thin. A row of guns, facing south, deployed along the Wheatfield Road protected the southern arm of the angle that extended southeast down the farmer’s dusty lane to protect Sickles’ left. In addition, Sickles had been promised support from both the Second and Fifth Corps to strengthen his advanced position.

Graham’s First Brigade and the First Division’s remainder held the Third Corps’ left, while General Humphreys’ Second Division occupied the right of the Third Corps’ line. No relation to Colonel Humphreys of the 21st Mississippi, General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, who hailed from a distinguished Philadelphia family, was a reliable West Pointer and a veteran of the Seminole War. A distinguished ancestry included Hum phreys’ grandfather, who had designed the U.S.S. Constitution, or “Old Ironsides.” Sickles’ salient was bolstered by double-strength levels of support infantry in the center. Along the Emmitsburg Road and the shallow, open ridge stretching toward Gettysburg, Graham’s 68th, 141st, and 57th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiments were aligned from south to north. The dependable 68th Pennsylvania anchored the line’s left along the Wheatfield Road.

Protecting the artillery, Graham’s reserve consisted of the 105th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, on the right of the brigade’s support line, and the 114th Pennsylvania. These two regiments were aligned across the open eastern slope of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. If the initial blue line was broken at the Peach Orchard, then these readily available reserves could advance swiftly to plug a hole in the line or reinforce any hard-pressed defensive sector.

To support the 1,515 infantrymen of Graham’s Pennsylvania brigade anchoring the First Division’s right, the six guns of the 15th New York Light Artillery, under Lieutenant Albert N. Ames, stood on the Peach Orchard’s knoll. Meanwhile, another three Federal batteries were aligned along the Wheatfield Road near the southern arm of the salient angle to the Peach Orchard’s left rear. Besides the massed array of Third Corps artillery, among the heaviest concentration of guns in the Peach Orchard sector were field pieces of the 1st Volunteer Light Artillery, consisting of the 5th and 9th Massachusetts Batteries, 15th New York Light Artillery, and Batteries C and F, Pennsylvania Light Artillery of the First Volunteer Brigade, Reserve Artillery. Meanwhile, the 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry of Ward’s Second Brigade held a position on the southern front of the Peach Orchard, just south of where the Wheatfield Road intersected the Emmitsburg Road.

North of the Peach Orchard to Graham’s right, Humphreys’ Division consisted of the Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts troops of the First Brigade, under General Joseph B. Carr. This fine brigade was aligned along the Emmitsburg Road and on the road’s east side north of the Abraham Trostle Lane. Meanwhile, Colonel William R. Brewster’s New York “Excelsior” brigade of Humphreys’ Division occupied the Emmitsburg Road line just northeast of the Sherfy house on the road’s east side. These experienced New York regiments were deployed north of the Abraham Trostle Lane on the right of Graham’s units that were aligned along the Emmitsburg Road. These New York troops sensed the seriousness of this key situation at the Peach Orchard salient, after Colonel Brewster ordered his troops to hold his elevated ground “at all hazards.” It was clear that some very hard fighting lay ahead.

Adding more infantry muscle to the Peach Orchard salient, two additional regiments, the 2nd New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, around 350 men, and the 7th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry, 275 men, of Humphreys’ remaining infantry brigade, under Colonel George C. Burling, were sent to reinforce General Graham’s Pennsylvanians along the Emmitsburg Road, after Burling received instructions from Birney to dispatch “two of my largest regiments” to reinforce Graham’s Pennsylvania brigade. The 7th New Jersey, under Colonel Louis R. Francine, formed to the left-rear of Captain A. Judson Clark’s New Jersey battery in protective fashion with the uniting of the Garden State’s infantry and artillery. The 2nd New Hampshire would soon support these six New Jersey guns to the right-rear of Captain Clark’s battery.166

With the keen eye of a veteran artillery commander in recognizing that the commanding Peach Orchard knoll along the Emmitsburg Road was the key to the battlefield, Colonel Alexander described the Peach Orchard sector before him in some detail. He explained how the infantry and artillery might of Sickles’ Third Corps’ “had taken position along this ridge [and] formed along this pike until he reached a cross road, where there was a large peach orchard, & there he turned off to the left & rested his flank in some broken ground” before Little Round Top. Most important, Colonel Alexander believed that, “now, the weakest part of Sickles’ line was the angle at the Peach Orchard.”167

With considerable insight, William A. Love indicated as much when he mockingly emphasized how “at the so-called ‘high-water mark of the Confederacy’ or elsewhere, no incident can surpass in grandeur the glorious achievements” of the upcoming attack of Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade on July 2. Indeed, the opportunity to exploit a key breakthrough at the Peach Orchard embraced even more potential for a truly decisive success, because the Union lines below and southeast of the Peach Orchard were relatively weak. A wide gap existed between the left of Graham’s Brigade, defending the Peach Orchard, and the right of Colonel P. Regis de Trobriand’s Brigade, First Division, Third Corps, on the Wheatfield’s west side. And most important, to the north, the Third Corps’ right on the Emmitsburg Road was not linked with the Second Corps’ left on Cemetery Ridge. Nearly half a mile of undefended ground lay in rear of Sickles’ left and the right of Hancock’s Corps.168

From Seminary Ridge, meanwhile, Barksdale’s Mississippians faced their high ground target as it stood forebodingly before them under the boiling July sun. If Barksdale could smash through this sector, especially at the salient, then the entire defensive front of the isolated Third Corps would cave in like a rotten apple hit with the full force by a baseball bat. Fortunately, no lengthy rows of sturdy rail fences stood erect on the gentle slope across the open ground leading up to the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Most of these barriers already had been torn down by skirmishers in preparation for the infantry assault, except relatively near to the ridgetop: an invaluable advantage which ensured that the upcoming attack would not be impeded, and no precious time would be wasted.

Here, along the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, stood the stately, but small, two-story farm house of red brick, the Joseph and Mary Sherfy home. Almost as if dropped out of the sky and into the middle of this pristine, rolling landscape of beautiful farmlands, the Sherfy House stood prominently on the slight ridge next to the road. The modest but stylish, farmhouse, with a small front porch, was situated amid a broad expanse of flowing fields, now covered with rich crops of oats, corn, wheat, and clover. The red brick Sherfy home was located immediately beyond, or just west, of the Emmitsburg Road and just before the west-facing north side of the salient angle. Now defended by hundreds of Yankees, the north side of the defensive angle ran as far as the eye could see along the dusty Emmitsburg Road. This narrow dirt avenue offered a means of rapid redeployment for either Union infantry or artillery in case of an emergency. Positioned on both side of the Sherfy barn, the six guns of Lieutenant John K. Bucklyn’s Company E, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, would give Alexander’s booming guns more than they could handle this afternoon.

The red Sherfy barn, a large wooden structure resting on a sturdy stone base in the German country style, looked huge compared to the Sherfy’s House, just to the north. Unlike the type of structures found in the Deep South and somewhat a puzzling contradiction of sorts to these Deep South soldiers from both a yeoman and a planter class culture, the German farmer’s barn was much larger than his own house.

From Barksdale’s view looking eastward, the barn offered a focal point by which to guide and target his offensive effort on the brigade’s left. Along with the fact that this was the position of Bucklyn’s six guns, the red barn of farmer Sherfy was a natural target for the Mississippians’ attack. In launching his charge, consequently, Barksdale and the Mississippi Brigade would have an ideal central visual point to direct their advance upon: a dominant sight that would not escape their view even after they descended into the slight depression between the ridges.

And farmer Sherfy’s barn stood only a few yards west of the road indicated to the observant Barksdale as the exact location of the Emmitsburg Road. After reaching the road in the Sherfy House sector, the Mississippians’ assault, after surging east, could then roll northeast and strike General Humphreys’ Division from the left flank. Barksdale’s plan of assaulting with three regiments—the 18th, 13th, and 17th Mississippi from left to right—above the salient angle promised to neutralize the Union defenders on the salient’s south side, which faced southwest, with a breakthrough. But more important for the ambitious goal of collapsing Third Corps resistance, Colonel Humphreys and his 21st Mississippi were to strike the point of the salient angle to capture the highest ground of the Peach Orchard to enfilade the salient’s southern arm along the Wheatfield Road from right to left. Hence, the guns of three Union batteries positioned along the Wheatfield Road would not be able to shift northwest to fire into the rear of the Mississippi Brigade’s assault barreling northeast when Barksdale attacked up the Emmitsburg Road. Also Barksdale planned to attack through the gap that existed between the widely separated Union artillery units aligned on the salient’s north side, so that his three regiments would avoid the salient’s south, where more Federal artillery was concentrated.