“Exceedingly impatient for the order to advance ”

BY MID-AFTERNOON on July 2, Longstreet’s divisions under Hood and McLaws were in position to begin their attack, supported by 54 guns under Alexander (who kept 8 in reserve). For all the clumsiness of Longstreet’s approach march, the Union high command had cooperated superbly by removing all Union cavalry from the left. Buford’s brigades had been on the field the prior evening, but had been ordered to Westminster to guard the army’s trains and to rest their horses. Thus Longstreet’s men were allowed to march to their assigned positions without a need for Jeb Stuart to screen their flank movement, as he had Stonewall Jackson’s at Chancellorsville two months earlier.

Nevertheless, if Meade still doubted the imminence of a huge Confederate attack on his left, there was no longer any doubt in Sickles’ Third Corps, as they could glimpse signs of infantry formations through the trees or between rises in the ground, as well as artillery rolling into position. Federal batteries had already begun feeling the woods in order to flush out the Rebels and develop their strength.

Finally, at about 3:45 PM, Longstreet’s artillery opened up. At that moment Meade had been conferring with Sickles and was about to order him to pull back his corps to the main Union line on Cemetery Ridge; however, the opening of the guns meant it was too late. According to Sickles, Meade hastily promised him support from the Second and Fifth Corps, before both men hurried back to their headquarters. By now the full Third Corps artillery had opened up in turn. In his diary, Private William Henry Hill, a seasoned member of Barksdale’s 13th Mississippi, wrote, “the cannonading was the most terrific I ever heard.”171

The Peach Orchard salient, bolstered by batteries, thousands of experienced front-line troops, and fresh reserves presented an awe-inspiring appearance. In the words of Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi, the high ground of the Peach Orchard sector now overflowed with thousands of men and dozens of cannon, and “seemed impregnable to a frontal attack.”172 Knowing that some of the most savage fighting of the war lay just ahead, Private Nimrod Newton Nash, 13th Mississippi, had attempted to reassure his wife Mollie in a June 28, 1863 letter, “Darling if I should get wounded here and left behind … if such befall me, for my sake don’t be uneasy about me, if not for your own, though I don’t fear any thing of the kind, for I have been in many hot places, and have come out safe. My trust is still in the same God that has always shielded me from harm.”173 But now in surveying the wide stretch of open ground flowing smoothly to gently ascend to the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, Private Nash now possessed less confidence for success. He knew that no place would be as “hot” as in the upcoming struggle, an especially brutal contest in which he was to receive his death stroke.174

On the Confederate right, General John Bell Hood was equally dismayed. As he told Longstreet about his trepidation to advance: “…we would be subject to a destructive fire in flank and rear, as well as in front; and deemed it almost an impossibility to clamber along the boulders up this steep and rugged mountain, and, under this number of cross fires, put the enemy to flight. I knew that if the feat was accomplished, it must be at a most fearful sacrifice of as brave and gallant soldiers as ever engaged in battle.”

Since neither side had any cavalry on that flank, Hood had sent out some of his Texas scouts to see what was behind the Round Tops, and they reported back that there was nothing but unprotected Federal wagon trains. Hood repeatedly applied for permission to go around the heights and hit the Union rear, but each time Longstreet refused, finally saying, “We must obey the orders of General Lee.” For Hood, the most lionhearted of Lee’s division commanders, to protest the attack was remarkable. However, as Longstreet later explained, if Lee had been on the spot the new intelligence could have been reported to him; however “to delay and send messengers five miles in favor of a move that he had rejected would have been contumacious.” This may possibly have been an indication of spitefulness on Longstreet’s part since he himself had argued for a further move to Meade’s right earlier in the day, only to be abruptly rejected. So if Lee wanted an attack “up the Emmitsburg road,” he would get it, regardless of the consequences.

Hood’s attack began around 4:00 with Evander Law’s Brigade on the right, supported by Henry Benning’s Brigade, and J.B. Robertson’s Brigade, supported by George T. Anderson’s, to their left. Immediately it was seen that holding to the Emmitsburg Road was a fantasy. They had a full Federal corps in front of them stretched to Little Round Top. Law’s Brigade began climbing those heights, a key to the battlefield, only to be met by a newly arrived brigade of the Federal Fifth Corps. Robertson’s Brigade attacked Ward’s Third Corps brigade head-on. Hood was spared from witnessing the culmination of his fears as he was knocked out of the battle with a severe arm wound in the first minutes. But soon all four of his brigades were engaged in a horrific fight, ranging from a jumble of boulders called Devil’s Den across to the Round Tops, and in particular in an open killing ground known simply to this day as the Wheatfield.

While Hood’s division battled, McLaws’ waited for Longstreet’s go ahead. His right hand brigade consisted of South Carolinians under J.B. Kershaw, another popular politician and attorney in gray, who like Hood, was not optimistic about the chances of success. He described how the Federal position was “heavily supported by artillery [and] the intervening ground was occupied by open fields, interspersed and divided by stone walls [and] The position just here seemed almost impregnable.”175

Kershaw was to be supported by General Paul Jones Semmes’ Georgia brigade. Semmes was the younger brother of the daring high seas captain of the Rebel raider C.S.S. Alabama, a former prewar Georgia militia officer, and former colonel of the 2nd Georgia Infantry. A tough-minded Catholic from southern Maryland, Semmes would soon be mortally wounded in the tempest below the Peach Orchard. Barksdale, in the front line to Kershaw’s left, was to be supported by the 1,400-man Georgia brigade of William T. Wofford, who had been a captain of a volunteer mounted company during the Mexican-American War. He yet possessed a Mexican lance that he had captured from the Castilian Lancers in a contest that he considered glorious. Wofford was a Georgia politician and lawyer, who had been anti-secessionist, like Colonel Humphreys, before inflamed sectional passions led to this most murderous of wars. He first won distinction as the commander of a lone Georgia regiment, the hard-fighting 18th Georgia attached to Hood’s famed Texas Brigade, and had most recently led his brigade to victory at Chancellorsville.

In preparation for the assault, Semmes’ four veteran Georgia regiments stood in neat lines behind Kershaw’s South Carolinians and adjacent to Wofford’s brigade behind Barksdale. Since McLaws did not filean official report on Gettysburg it can only be conjectured, but the order of his brigades may have been influenced by their respective casualties at Chancellorsville. Wofford’s and Semmes’ men had suffered more in dead and wounded in that battle than Barksdale’s and Kershaw’s brigades, so for that reason may have been placed in support positions. Barksdale’s losses in his solo defense of Marye’s Heights during that campaign had lost largely in prisoners when Sedgwick’s Corps overran the position, but not so heavily in killed and wounded.

Meanwhile, to the Mississippi Brigade’s left stood the troops of General Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox’s Alabama brigade of General Richard H. Anderson’s Division, Ambrose Powell Hill’s Third Corps.

Colonel Alexander summed up the tactical alignment among the Confederates as the attack got underway: “Each of our divisions formed a double line of battle. Two brigades in the front line & two in the rear. McLaws was on our left, & the middle of his line was opposite the Peach Orchard, where Sickles’ line made a large obtuse angle back to his left. A wood enabled us here to come up within about 500 yards.” This was in keeping with Longstreet’s penchant for hard-hitting attacks, a technique he would perfect the following September at Chickamauga.176 In contrast, to McLaws’ left was Richard Anderson’s division of A.P. Hill’s Corps, which aligned its brigades in a long, single line, none of them having a supporting or follow-up unit at all.

While Barksdale’s troops lay in line on the reserve slope amid the shade of Pitzer’s Woods, the artillery duel between the Confederate guns along Seminary Ridge and the Peach Orchard’s artillery raged. With four Union batteries of more than twenty guns defending the Peach Orchard proper, Colonel Alexander’s concentration of firepower of more than 50 guns continued to hammer Sickles’ lines in an effort to gain an advantage before the attack. In total, nine Federal batteries of the Third Corps and the Reserve Artillery, more than forty guns, bolstered the Peach Orchard sector, after additional Federal batteries, from the Fifth Corps and the Reserve, were rushed forward and unlimbered to counter the intense Rebel bombardment

Only age twenty-eight, Georgia-born Colonel Alexander described his tactical “long arm” objective before the Peach Orchard: “I had hoped, with my 54 guns & close range, to make it short, sharp, & decisive. At close ranges there was less inequality in our guns, & especially in our ammunition, & I thought that if ever I could overwhelm & crush them I would do it now. But they really surprised me, both with the number of guns they developed, & the way they stuck to them. I don’t think there was ever in our war a hotter, harder, sharper artillery afternoon than this.” The twenty-eight-year-old Alexander had been appointed on the field by “Old Pete” to command all of Longstreet’s artillery over a more experienced, older officer, Colonel James Walton, whose ire was understandably raised in consequence. Alexander had done exceptionally well at both Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, but the Gettysburg challenge was more formidable than anything he had yet experienced.177

Lee had originally hoped that Alexander’s concentrated firepower would clear the way for a successful oblique attack up the Emmitsburg Road to strike the Union left flank. But the flank was no longer where he thought it was, if it ever was in the first place. The Union line had been designed to stretch all the way to the Round Tops, which overlooked the Emmitsburg Road, but now, thanks to Sickles, the flank was on the road itself, prepared and waiting for an attack. Thousands of veteran Third Corps soldiers were now solidly arrayed in lengthy defensive lines, withstanding the punishment delivered by Alexander’s concentration of guns. Shells exploded in Sherfy’s orchard, tearing off branches and thick, green leaves of the stately peach trees, but Sickles’ tried veterans held firm under the pounding.178

Meanwhile, on the eastern fringe of Pitzer’s Woods along the slope just before the ridge’s crest, Barksdale’s men took punishment of their own, because Union gunners out-shot their targets of Alexander’s guns positioned before the brigade. Private John Saunders Henley, 17th Mississippi, described how the shells “tore the limbs off of the trees and plowed gaps through his men.”179 Positioned in the center of McLaws’ line, along the ridge, and astride the Wheatfield Road, Alexander’s fast working guns continued to rake the Peach Orchard with a barrage of shot and shell, while the field pieces of Colonel Henry C. Cabell’s artillery battalion, positioned along the ridge below the Wheatfield Road, bellowed in anger from McLaws’ right. With the Rebel cannoneers working their guns rapidly amid the drifting low-lying clouds of sulfurous smoke, Alexander’s “long arm” units suffered a steady attrition during the intensive artillery duel.

On high ground north of the Wheatfield Road, the four booming howitzers of Captain George V. Moody’s Madison Light Artillery’s blazed in anger before the 21st Mississippi, on the brigade’s right. Manned by expert gunners, including French-speaking, dark-featured Creoles, these Pelican State cannon pounded the Peach Orchard with everything they had from their wooden ammunition chests. Moody himself was a lawyer from the picturesque community of Port Gibson, which Grant had captured on May 1, 1863, and had old scores to settle with the boys in blue.

With Rebel cannoneers falling fast to Union return fire, and two guns dismounted, Alexander was forced to find infantry volunteers to help man the guns. As he wrote, “I had to ask General Barksdale, whose brigade was lying down close behind in the wood, for help to handle the heavy 24-pounder howitzers of Moody’s battery. He gave me permission to call for voulunteers, and in a minute I had eight good fellows, of whom, alas! We buried two that night, and sent to the hospital three others mortally or severely wounded.” Among Barksdale’s volunteers who stepped forward to serve the Louisiana guns were two young brothers from the 17th Mississippi. Moody was delighted to receive these strapping Mississippians, who could be depended upon.180 A veteran member of the Buena Vista Rifles, Private John Saunders Henley, 17th Mississippi, described how the Union artillerymen “killed so many of our artillerymen that some of our infantrymen had to go and help them handle the guns.”181

Alexander’s cannon poured their fire into the Peach Orchard, blowing up trees, fences and unlucky defenders caught amid the storm of shot and shell. From south to north along the smooth ridge-line, Alexander’s lengthy row of guns in the Mississippi Brigade’s sector consisted of the fast-firing guns of Captain Parker’s Virginia Battery, Captain Osmond B. Taylor’s Virginia Battery, Moody’s Louisiana Battery, and Lt. Brooks’ South Carolina Artillery.182

Unlike in Chancellorsville’s blinding forest, and reminiscent of the nightmarish artillery storm at Antietam, the Union artillery, manned by veteran gunners and capable young commanders, rose magnificently to the challenge. Colonel Alexander continued to be frustrated by the fact that his artillery concentration could not “crush that part of the enemy’s line in a very short time, but the fight was longer and hotter than I expected.” Instead, the Federal guns remained “in their usual full force and good practice” on the high ground before the Georgian, who gained a new respect for his counterparts in blue. “At last seeing that the enemy was in greater force than I had expected,” he wrote, “I sent for my 8 reserve rifles, to put in the last ounce I could muster.”183

Meanwhile, Longstreet made final preparations to hurl more troops forward. Hood’s attack had stalled in the face of Union reinforcements, so that instead of readying the Federals for a knockout blow, Hood’s men themselves needed help. Providing a signal for the assault to commence in McLaws’ sector, the barking row of Confederate artillery on the right finally ceased firing. Kershaw’s South Carolina Brigade stepped off, and though originally intended to strike Sickles’ left flank at the southern end of the Peach Orchard salient, they now headed straight into the conflagration that had nearly swallowed Hood’s men.

It was about 5:00 PM when, beneath their Palmetto state flags of silk, the veteran South Carolinians pushed east below the Peach Orchard salient, targeting a Union stronghold Kershaw called the “stony hill.” However, his left flank was immediately assailed by a Federal gun line on his left, severely disrupting his attack. Long after the war Kershaw wrote: “When we were about the Emmitsburg Road, I heard Barksdale’s drums beat the assembly and knew then that I should have no immediate support on my left, about to be squarely presented to the heavy force of infantry and artillery at and in rear of the Peach Orchard.” This implication that Barksdale was slow to attack that afternoon has unfortunately influenced students of Gettysburg ever since. In fact, Barksdale had been appealing to both McLaws and Longstreet for permission to launch his men almost since arriving at Seminary Ridge. In his Official Report, written soon after the battle, Kershaw said that Barksdale “came up soon after, and cleared the orchard.”

The delay in the Mississippi Brigade’s attack was no fault of Barksdale, who had been “chafing” to launch his attack. McLaws remembered that “Barksdale had been exceedingly impatient for the order to advance, and his enthusiasm was shared in by his command.”184 He was eager to strike a blow, knowing that so much delay allowed the Yankees time to strengthen the Peach Orchard sector while reducing his chances for success. Unlike Longstreet, who remained hesitant today to embark upon the tactical offensive, Barksdale and his top lieutenant, Colonel Humphreys, were eager for the charge, sensing the opportunity that lay before them. Both of these officers were “straining at the leash” and confident that they could take the position in front of them. To add to their chagrin, the neighboring brigades to their right were already engaged in full-scale battle while the Mississippians were simply forced to remain stationary under artillery fire. With his battlefield instincts rising to the fore, an optimistic Barksdale “sensed victory” on this late afternoon.

Barksdale now had his 1,600 soldiers ready for their greatest challenge to date. All the while the Mississippi troops laid low to escape the incessant hammering that resulted from Union artillery overshooting their targets in attempting in vain to knock out Alexander’s artillery. Union artillery sent shells flying through the belt of woods, though without causing any panic in Barksdale’s gray and butternut ranks. But all the while, the Mississippians’ casualty lists lengthened as the bombardment grew in severity during this nerve-wracking experience. For what seemed like an eternity to them, the troops, in Colonel Humphrey’s words, continued to be “subjected to a terrific cannonading” from the angry Union guns.

The heightened tension and eagerness to strike among Barksdale’s troops steadily mounted, especially after a shell exploded in the midst of Company F (Tallahatchie Rifles), 21st Mississippi. The explosion sent unfortunate soldiers flying in every direction, and iron fragments tore through the legs and thighs of Captain H. H. Simmons and Privates John T. Neely and John H. Thompson. Other dependable men went down in the explosion, including J. T. Worley, one of seven family members in the ranks, who was killed. Especially when unable to strike back at the Yankees, the pent-up rage among the simmering Mississippians gradually increased, while the bombardment continued unabated. And only Barksdale’s ordering the charge would now release it.

Raising his anger and sense of frustration because of the long delay in receiving orders to attack, Barksdale witnessed the bloody carnage which tore through Company F’s ranks, but yet spared the Benton brothers who remained close together. The white-haired general in gray became even more determined not to have his boys killed for nothing, especially without striking back at the blazing Union cannon, especially Bucklyn’s Rhode Island guns that were causing so much damage. Upset at the useless loss of life among his boys without being allowed to do anything about it was too much for Barksdale to bear. He realized that the brutal punishment being delivered from the Union artillery could only be stopped if he took those lethal guns around the Sherfy House and barn himself. Barksdale’s pent-up anger would soon play a role in fueling one of the great infantry assaults of the war.

Ohio-born Lieutenant William Miller. Owen, a promising Washington Artillery officer and graduate of Gambier Military Academy, described how the Mississippians under Barksdale’s command “were as eager as their leader, and those in the front line began to pull down a fence behind which they were lying. “Don’t do that, or you will draw the enemy’s fire,” barked Longstreet. At this time, “Old Pete” was yet hesitant to order Barksdale forward because he hoped that Hood’s attacks on Meade’s left flank would draw reinforcements from the Peach Orchard sector.

Anchoring the Mississippi Brigade’s right was the ever-reliable Colonel Humphreys and his 21st Mississippi, the brigade’s elite regiment. Humphreys’ right was aligned next to the Wheatfield Road, which meant, appropriately for the hard fighting that lay ahead, this crack regiment was aligned more directly before the salient angle of the Peach Orchard than any other in the brigade. On this day the 21st Mississippi, numbering about 424 men, would achieve the most remarkable gains of any of Barksdale’s regiments, and perhaps of any other regiment on the field, Confederate or Union. Barksdale’s largest regiment was the 13th Mississippi, with 481 men, followed by the 17th Mississippi with 468, and then the 18th Mississippi, which mustered only 242 for the battle.vii

Under B.G. Humphreys, the 21st Mississippi was the best led and most dependable regiment of Barksdale’s Brigade, with its fighting spirit demonstrated on one battlefield after another. In his diary on April 13, 1863, Private Joseph A. Miller, bestowed an indirect compliment to the 21st Mississippi’s feisty qualities even off the battlefield: “There was a considerable row in the brigade [when] some of the 21st were playing ball, which was against orders on Sunday. The provost guard undertook to stop it and I supose [sic] was rather too harsh, which caused the 21st to resist the guard [until they] had to call out the whole force of the guard [but not before] a good [many] weapons were drawn, but no blood spilt.”185 The rebellious leaders were thrown into the guardhouse. However, somewhat ominously, Private Miller noted the lingering animosity that existed between the 21st and the 17th Mississippi. He scribbled in his diary how afterward, the soldiers of the “21st have been consoling themselves with breathing out threatenings against the guard today, but I hope we shall heare [sic] nothing” of another clash.186 Clearly, the evercombative 21st Mississippi soldiers were almost as eager to fight fellow Mississippi Rebels as the Yankees.

Now on this day at Gettysburg, young Captain Middleton of the 17th Mississippi, the unfortunate provost marshal who had become the focal point of the 21st Mississippi’s wrath, now stood before his line of Panola County soldiers on this hot afternoon, perhaps yet holding a grudge against the 21st Mississippi boys for that April 12 melee. If so, any lingering animosity he harbored was about to finally come to an end, because he soon received his death stroke in the upcoming attack and would never see his beloved Batesville, Mississippi, again.187

Indeed, fierce regimental pride, and thus competition, had long existed between the Mississippi Brigade’s regiments. During the previous winter this rivalry had played out in hard-fought snowball battles, in which maneuvering and attacks helped to fine-tune the Mississippi troops for July 2. In his diary, Private Miller described one such clash that surged back and forth over the snowy fields outside Fredericksburg on February 25, 1863: “The boys had another big fight to day with the 21st regt snowballing [and] they fought about two hours, when the 17th come off victories [sic] again.”188 Indeed, the 17th Mississippi was larger than the 21st Mississippi, which was a regiment long familiar with overcoming the odds.189 Now with Barksdale’s men sweating amid the searing afternoon heat and humidity of summer, the February snows seemed almost like a century ago to the boys in the ranks. Perhaps a few Magnolia State soldiers now realized that those sweeping mock battles in the snow had been part of a conditioning process that would assist them in reaping success on this most decisive of afternoons.190

While the Mississippi Brigade remained in position among the tall trees of the eastern edge of Pitzer’s Woods along Seminary Ridge’s southern end, Warfield Ridge, the sight before Barksdale was awe-inspiring. Under the heavy bombardment, Private McNeily described how the 21st Mississippi lay “under the crown of a low ridge, five or six hundred yards distant from the position of assault [and] open fields, fences and scattered farm houses lay between [while] parallel with our line, and at the base of the Peach Orchard hill, ran the Emmitsburg road, between two high rail fences [and] farther to the left a picket fence lay beyond the road.”191With a gift for understatement, Private John Saunders Henley, 17th Mississippi, marveled how the “Federals were strongly posted.”192

Even though Hood’s Division, attempting to turn Meade’s left flank, had initiated Longstreet’s assault around 4:00 PM, the Mississippi soldiers yet remained idle for what seemed like an eternity, while the savage contest roared to the southeast at Little Round Top and the most eerielooking spot on the Gettysburg battlefield, the Devil’s Den. For an agonizing hour and a half thereafter, Barksdale’s men listened to the crackling musketry of the escalating battle. Like a wildfire raging out-of-control, the slaughter flowed slowly north east and began to crisscross the twentyacre Wheatfield sector. Here, Kershaw’s South Carolina troops ran into trouble in meeting stiff opposition, and were dutifully followed it into by Semmes’ Brigade, while the ever-intensifying fight raged to higher levels from right to left. As Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi, described the struggle, “The noise of battle, when Hood’s division opened the fight, was heard far to our right soon after 4 o’clock [and] the resistance was most obstinate, and the wave of attack was longer in reaching us than calculated.”

The Mississippians’ gear included Yankee and new Confederate knapsacks (including more than 100 new ones issued to the 21st Mississippi soldiers on April 28), haversacks, mess gear, and blankets. But by this time, this cumbersome gear had been piled behind the lines in Pitzer’s Woods to lessen each soldier’s load for the upcoming the attack. “Well shod and efficiently clothed,” Barksdale’s men wore over their gray jackets, with brass Mississippi buttons, leather cartridge-boxes and wooden and tin canteens, which they needed on this scorching day, if the attack was to be continued all the way to Cemetery Ridge as planned. Mississippi canteens had been recently filled with cold creek water from Pitzer’s Run or the spring that flowed north from the Sherfy House, just before they ascended the relatively steep, timbered western slope of Seminary Ridge.

Taken from the vanquished enemy on hard-fought fields in Virginia and Maryland were some of the Mississippians’ favorite weapons, especially Springfield rifles. Well-known for their superior marksmanship, Barksdale’s hardened veterans were experts at using rifled muskets with deadly affect. One Northerner who had felt the Mississippians’ wrath wrote how these Rebels “from Mississippi … were more vicious and defiant” than other Army of Northern Virginia troops.193 In addition, Barksdale’s veterans wore all manner of headgear, both civilian, especially wide-brimmed slouch hats, and military, including “jaunty kepis of gray and blue.” Private James J. Lampton, Company K (Columbus Riflemen), 13th Mississippi, wore a low-crowned straw hat that was relatively light and cool on hot days like July 2. Armed with an array of .577 Enfield rifles, sturdy, dependable weapons imported from England, captured .58 caliber Springfields, and .58 caliber “Richmond Rifles,” these Mississippi Rebels were ready for action with well-balanced weapons so clean that they now shined brightly under the July sunlight.194

Most of all, and as penned by Private Ezekiel Armstrong, of the Magnolia Guards, 17th Mississippi, in his diary, the Mississippi Brigade’s soldiers were now “determined to lay my life on the altar of my country or see her free.”195 Destined not to live to see his twenty-second birthday, Private Armstrong’s words were not hyperbole.196 And thirty-two-year Lieutenant Marcus D. Lafayette Stephens, a respected physician from Sarepta in Calhoun County, emphasized how the all-consuming goal of the 17th Mississippi men was now “to set our country free.”197 And now as never before, the upcoming assault held that golden promise, if the attack could be continued all the way to Cemetery Ridge.

Some of Barksdale’s men, however, began to sense that they personally would not get that far. On the Mississippi Brigade’s right flank, Captain Isaac Davis Stamps was wrapped up in his own ominous thoughts. Commanding Company E, the Hurricande Rifles, of the 21st Mississippi, Captain Stamps was haunted by a dark premonition that now nagged at the fiber of his being, He was thoroughly convinced that he was going to be killed in the forthcoming assault. Nevertheless, the revered captain was bound by a deep, biding obligation to lead his troops in what he knew was to be his final attack. After all, his revered uncle, Jefferson Davis, now sat in the Confederate White House in Richmond. His mother, Lucinda, was the sister of the president, who possessed only the fondest of memories of her. And the handsome captain’s father-in-law was Colonel Humphreys. Appropriately, Captain Stamps now served as one of Humphreys’ top lieutenants, and his heavy burden of military, family, and moral obligations was heavy, weighing on his mind and soul.198

Carrying the same ornate saber that Jefferson Davis had carried at Buena Vista to win glory in Mexico in February 1847, Captain Stamps was correct in his premonition. He would not survive the upcoming attack nor see his wife, Mary Humphreys, who he had married in 1854, his two little girls, or his beloved Rosemont Plantation again. On his last furlough home, Captain Stamps had made his wife Mary, age twentysix, promise to retrieve his body (especially from northern soil) and return it to Mississippi should he fall. Perhaps by way of a battlefield death, Captain Stamps had reconciled himself to the bliss of eventually rejoining his two deceased children, including Sallie who died in the spring 1862, when he was far from home battling for his country. To Captain Stamps’ great relief, Mary had promised to have his body returned to the family’s burial plot at Rosemont to be buried by Sallie’s side, when killed in battle. Stamps was now peacefully resigned to his tragic fate.199

Private Archibald Y. Duke, of Company C, the Quitman Grays, 17th Mississippi, likewise was consumed with a dark premonition just before the attack. Consequently, he turned to his brother, Private James W. Duke, who everyone called Jim, and made a request that he had never made before. With uncharacteristic seriousness, Archy asked his brother to be sure to write a letter home after the upcoming battle. But it was not Jim’s turn to write, his brother protested. Then Archibald explained with firm conviction: “Something is going to happen to-day.”200 Indeed, Private Archibald Duke, who had silently prayed that God would take him at Gettysburg instead of his brother, was about to receive a severe leg wound, which would become gangrenous and take his life.201

Nevertheless, despite forebodings, the Mississippians’ fighting spirit today was early evident. Riding atop a bouncing Louisiana caisson that kicked up a trail of dust, Captain Charles W. Squires, Washington Artillery, was hailed by Lieutenant Colonel John Calvin Fiser, 17th Mississippi. Fiser, one of the most respected Mississippi Brigade officers, yelled out that “he would soon have some guns for me to replace those lost on Marye’s Hill,” during the so-called second battle of Fredericksburg in early May 1863, when the Mississippi Brigade had supported the Washington Artillery.202 Private Dinkins, 18th Mississippi, described how Fiser “filled to a high degree the most exalted idea of a dashing cavalier, and proud as a knight of the crusades. We have seen him at the head of his regiment, on that light bay. His face would be radiant. He was always looking out for his men. He was the same courtly, elegant gentleman under fire that he was in camp, or on the march.”203

Lieutenant Owen of the Washington Artillery described a moment when Barksdale suddenly rode up to him and yelled, “I hope we will have better luck this time with your guns than we had on Marye’s Hill,” where the battery position had been overrun by the overwhelming might of Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps. Meanwhile, the artillery duel raged with an intensity not seen by the Mississippi Rebels since Fredericksburg. Private McNeily described how the fierce artillery exchanges resulted in “a din that was deafening [and] as fast as the gunners could load they concentrated a fire on the Peach Orchard, which must have been destructive and demoralizing.”204

Unfortunately for the Mississippi Brigade, however, the Confederate bombardment was relatively ineffective. Thanks to the height of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, General Hunt had correctly visualized how Union troops positioned in prone positions behind the crest would be protected from even the most intense artillery bombardment. A 57th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry soldier described how “our regiment was lying in a field a few rods in the rear of the Sherfy house, which stood on the opposite side of the road. The 105th Pennsylvania was on our right, and the 114th on our left. For two hours we lay here under the hottest fire of artillery we had yet been subjected to. The enemy had some thirty pieces of artillery planted on the ridge to the south and west of us, hurling their missiles toward us as fast as they could work their guns. Fortunately most of them were aimed too high to do us injury … .”205

All the while, the Mississippi officers and men grew increasingly anxious to attack, despite the Peach Orchard’s formidable appearance. Barksdale’s veterans knew that they were in for serious fighting today, realizing that high casualties were inevitable. With sharpened socket bayonets and clean, well-maintained muskets, the Mississippians remained under their relatively slight cover of the hardwood timber and reverse slope, knowing that there was about to be a good many more widows and orphans across the Magnolia State.

Meanwhile, with the long delay in launching the attack, the tension in the Mississippi Brigade’s increased to the breaking point. A sharp increase in Union activity before the Mississippians’ position seemed to indicate that the Federals were even considering a pre-emptive blow. Already, an advancing lengthy line of 63rd Pennsylvania skirmishers had swung off the high ground and onto the slope that led to slight bowl-like depression between Seminary Ridge and the Peach Orchard. Moving with crisp precision and mechanical-like ease that indicated that these men were veterans, the Pennsylvania skirmishers began to bang away in the stifling heat. Under the searing sun, the Yankee skirmishers busily loaded and fired, sending bullets through the fast-working Louisiana artillery crews of Captain Moody. Minie balls then continued on to zip over the prone Mississippians, while other lead balls struck trees and limbs with sharp cracks.

As the line of Yankee skirmishers advanced through the open fields, the ever-aggressive Barksdale became even more convinced that the best defense now called for a good offense. For all that he knew, the entire Third Corps was now preparing to pour off the dominant high ground of the Peach Orchard in an attempt to outflank the left of Hood’s Division to the southeast. If such an attack succeeded, then Lee’s army, overextended for nearly six miles in sprawling exterior lines around the Army of the Potomac, would be destroyed.

Champing at the bit and with the tension as well as his temper rising, Barksdale had repeatedly ridden up to his division commander and implored: “General, let me go; General, let me charge!” But McLaws had not yet received attack orders from Longstreet. After Barksdale had approached him more than once with the same request, McLaws finally informed the “fiery impetuous Mississippian” to just be patient.

When his corps commander passed near the Mississippi Brigade, Barksdale confronted Longstreet. He begged for the opportunity to strike while the Third Corps’ position remained vulnerable: “I wish you would let me go in, General and I will take that battery in five minutes.” No doubt amused by the impetuous nature of the gray-haired Mississippian who was overwhelmed by impatience and frustration, Longstreet merely replied, “Wait a little, we are all going in presently.”206

In the meantime, Private McNeily of the 21st Mississippi, for one, was galled by the heavy bombardment, writing, “While waiting their turn, Barksdale’s men lay low under the fire of artillery and infantry in their front, which they were not allowed to return for an hour or more. Where they were well covered the casualties were few; but where the line was exposed the punishment was severe. The severest of all tests on troops, to receive fire without returning it, was born unflinchingly. In total the brigade would lose 133 men (19 killed and 114 wounded) in Pitzer’s Woods under the artillery fire before they had an opportunity to strike back. It but increased the impatience of Barksdale and his men to get the order to move on the offensive batteries.”207

With a far-sighted vision which shortly paid the highest of tactical dividends on this most open of battlefields yet seen by the Mississippi Rebels, consequently, Barksdale made a number of decisions to ensure the chances for greater success. First, he ordered “a detail of ten men from each company [to draw] twenty rounds of extra cartridges for the bloody fray” that lay ahead. These extra rounds hurriedly gathered from the ordnance wagons in the rear now gave the Mississippians not the usual forty, but a total of sixty rounds in their leather cartridge-boxes. The brothers Archibald and James Duke were among those who secured the vital extra rounds, which would be much needed this afternoon, for their company in the 17th Mississippi.208

Barksdale also issued orders for his soldiers not to place percussion caps on the nipples of their rifles. He reasoned that this would ensure that his attackers would not be tempted to halt and return fire too early in the assault. Indeed, this wise tactic would allow the charging Mississippi Rebels to cross the open stretch of killing ground and up the western slope of the Emmitsburg Ridge Road at a faster pace. Such an early unleashing of return musketry would only slow the attack, while inflicting minimal damage on the high ground defenders. After having carefully calculated the terrain and tactics, Barksdale realized that even a few minutes of wasted time might spell the difference between success and failure.

In addition, Barksdale ordered his officers, except regimental commanders (who needed to be mounted to lead their troops) and staff officers (who needed horses to communicate orders), not to go into the assault mounted as usual, but on foot. Veteran soldiers in blue, including advanced skirmishers, made sport out of shooting Rebel officers off their horses. Barksdale wanted to save as many officers’ lives as possible, enhancing the chances of a successful attack. Personally, Barksdale planned to serve as an inspirational beacon while mounted, upon which the eyes of his men could follow during the attack. He would lead the assault across the open ground by example and for all to see. But, of course, this was a deliberate calculation that might have cost Barksdale his life.

So as not to slow the attack, Barksdale had already ordered his soldiers to remove excess equipment. One 18th Mississippi officer recorded how “the order was given to ’strip for the fight’. The men carried their scanty change of clothing wrapped in their blankets and thrown over their shoulders; each regiment piled these in a heap” behind the lines. Haversacks, blanket rolls, and mess gear now lay in neat piles, almost as if these young soldiers expected everyone to return from the attack unscathed. But tragically, nearly half of these men never reclaimed their belongings, including the precious ambrotypes and daguerreotypes of wives, children, sisters, and other family members.

Barksdale also issued orders to his soldiers, once unleashed upon his orders, to advance “in closed ranks.” Clearly, reaching the high ground would now largely depend upon the Mississippians’ discipline and the speed of their advance. Barksdale had also ordered a lengthy picket fence to be torn down before the brigade. Of course, all of these timely measures were initiated so that his troops would cross the open fields as rapidly as possible to minimize losses. If success was to be won on this after -noon, then the Mississippi Brigade must gain the Emmitsburg Road Ridge in relatively good shape for any hope of continuing farther east to Cemetery Ridge to reap far greater gains before nightfall. With a clear tactical vision of what it would take to win a decisive victory today and quite unlike either a reluctant Longstreet or McLaws, Barksdale orchestrated a well-thought-out scenario to enhance the chances for success in what other commanders might have seen as a hopeless situation.

All the while, the Mississippi soldiers listened patiently to the roaring gunfire of the battle that gradually grew louder, rolling like thunder from south to north. To the Mississippians, this escalating gun-fire told them of the continuance of Confederate attacks en echelon all along the line to their right, and that they were meeting stiff resistance from the boys in blue.

Thanks to veterans’ instincts, Barksdale’s seasoned warriors from the Magnolia State knew that the time to go forward was finally nearing. This intuitive sense was only additionally confirmed when they saw Barksdale meeting with his regimental commanders to give last-minute instructions. With the attack imminent, Barksdale continued to lay forth his tactical ideas and last minute instructions to his regimental officers, Colonel Carter of the 13th Mississippi, Colonel Holder, 17th Mississippi, Colonel Griffin, 18th Mississippi, and Colonel Humphreys of the 21st Mississippi. For the upcoming attack to succeed, there could be no errors, confusion, misunderstanding or miscommunication to sabotage prospects for a successful assault. Solemnly and with firmness, the former Mississippi Congressman informed his direct subordinates of the hard work that lay ahead, articulating his plans for the coming attack. Barksdale then pointed to the lengthy rows of cannon and formations of blue along the crest of the Emmitsburg Ridge and on the high ground of the Peach Orchard. In a stern voice, he emphasized, “The line before you must be broken—to do so let every and man animate his comrades by his personal presence in the front line.”209

James Longstreet recalled how his Mississippi brigadier was yet “chafing in his wait for orders to seize the battery in his front.” Barks-dale’s “thirst for glory was as sharp in Pennsylvania as it had been on his great day at Fredericksburg, where Lee to his delight had let him challenge the whole Yankee army,” summarized historian Shelby Foote. But his motivations ran much deeper. As so often in the past, Barksdale and his troops were determined to demonstrate to Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia exactly what this crack Mississippi Brigade was capable of accomplishing. Indeed, “never was a body of soldiers fuller of the spirit of fight, and the confidence of victory,” wrote Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi.210

Meanwhile, the roar of the Confederate artillery pieces finally ceased echoing over sun-baked Seminary Ridge, and in the day’s intense heat without a wind to blow it away, the thick, white clouds of smoke lingered low over the field. The powder-grimed, sweating Rebel artillerymen of Alexander’s battalion rested in exhaustion beside their smoking guns, after what they hoped had been a job well done to assist Barksdale’s in-fantrymen in their assault. The sudden, haunting silence said everything to the Mississippi Rebels. About to charge into the teeth of the formidable Peach Orchard salient, Private McNeily and his 21st Mississippi comrades, on the brigade’s right flank, now realized that when “the order was given by the battery commanders to cease firing, every man in the brigade knew that ‘our turn’ had come at last.”211

At long last, the great wreaths of sulfurous smoke, whitish and thick as an early morning fog, began to slowly rise higher into the clear, hot sky. To Barksdale’s Deep South soldiers, the sudden unveiling of the curtain revealed the rows of bronze barrels of multiple Union batteries, sites aimed at the open ground in front of them, and the lengthy lines of bayonets of one veteran Union regiment after another along the high ground. All of this formidable might was just waiting for Barksdale’s men.

Meanwhile, Barksdale made final preparations to lead his troops into hell itself. Ironically, one of the best descriptions of Barksdale’s physical appearance at Gettysburg came from a Federal surgeon who wrote how the Mississippi general was “large, corpulent, refined in appearance, bold, and his general physical and mental make up indicated firmness, endurance, vigor [and] quick perception …” At this time, Barksdale was not dressed in a fine, double-breasted gray uniform coat like most of Lee’s generals, such as Semmes who wore a resplendent uniform for all to see. Not surprisingly, Semmes was mortally wounded in the open fields of the John W. Rose farm, southeast of the Peach Orchard, paying a high price for his pride.

Instead of committing the folly of making himself a much too conspicuous target and symbolically in a display that revealed a close identification with his men, Barksdale was now “dressed in the jeans of [the Mississippians’] choice [and] his short roundabout was trimmed on the sleeves with gold braid. The Mississippi button, with a star in the center, closed it. The collar had three stars on each side next [to] the chin [and he wore under his uniform coat] a fine linen or cotton shirt which was closed by three studs bearing Masonic emblems. His pants had two stripes of gold braid, half an inch broad, down each leg.” The 13th Mississippi’s capable adjutant, E.P. Harman, described how “Gen’l. Barksdale was dressed in a Confederate gray uniform and wore a soft black felt hat [and] rode a bay horse.” Especially when mounted and despite his less than stellar horsemanship in a cavalier-inspired army known for its superior riders, Barksdale presented an inspiring appearance on the battlefield. Like their popular commander, the Mississippi soldiers of all ranks wore the dirty, dust-covered, and grease-stained jean uniforms, which were either dyed gray or butternut.212

On his finest day and one that was very nearly his last, Colonel Humphreys, Barksdale’s dependable “right arm,” likewise wore a denim uniform of plain brown wool. The colonel’s uniform coat was double-breasted, with the three gold stars of a full Confederate colonel stitched on his collar. Like Barksdale’s homespun apparel today, Humphreys’ uniform possessed a distinct symbolism that indicated the close camaraderie and team spirit the existed between officers and enlisted men. The uniform had been presented to him by an aid society of patriotic Southern women from Woodville, Mississippi, during a solemn ceremony.

McLaws described Barksdale, his most aggressive lieutenant, as “the fiery, impetuous Mississippian” upon whom he could rely. Private Mc-Neily also recalled Barksdale’s inspiring presence at this time, when superior leadership was never more important or timely: “General Barksdale was a large, rather heavily built man of a blond complexion, with thin light hair. He was not a graceful horseman, though his forward, impetuous bearing, especially in battle, overshadowed and more than made up for such deficiencies. He had a very thirst for battlefield glory, to lead his brigade in the charge [and] as this was destined to be my last sight of him, impressions of his appearance are indelible. Stamped on his face, and in his bearing, as he rode by, was determination ‘to do or die’.”213

After Confederate artillery ceased roaring, Lieutenant Owen, Washington Artillery, described the moment when the dignified Barksdale now “called for his horse, mounted, and dashed to the front” in a swirl of dust. Meanwhile, Mississippi drummer boys furiously beat their instruments. The pounding of the drums were those heard by General Kershaw and his South Carolina boys as they advanced around 300-400 yards to the southeast. With everyone now standing in their assigned place in line before a lengthy stone wall that ran between Pitzer’s Woods and the open fields, Barksdale ordered his men to fix bayonets. The metallic ringing of hundreds of bayonets being attached to muskets echoed over the green fields and pastures bathed in bright sunlight, clanging louder than the pounding drums.214

One of Barkdale’s young aides, who remained mounted, recalled that the Mississippi general’s face was “radiant with joy,” just before being unleashed, despite facing his greatest challenge to date. In the words of nephew, Captain Harris Barksdale, “the time had come when Mississippians must try their hand.” Like a warrior-prophet from the pages of the Old Testament, Barksdale was confident of success in part because “he was proud of his men, and never doubted them,” wrote Private Dinkins of the 18th Mississippi.215

In a position to reverse the war’s course if successful, the young men and boys in the Mississippi Brigade ranks sensed the golden opportunity presented by the Peach Orchard salient’s vulnerabilities. Most of all, these hardened veterans knew that a good many Mississippi Brigade members would die before the sunset of July 2. Because most of Barksdale’s men were zealous “Christian soldiers of the grandest type,” wrote Private Dinkins, 18th Mississippi, they now prayed silently to themselves, asking for God’s mercy, before moving forward into the vortex of hell itself. And these elite fighting men from across Mississippi made sure that Holy Bibles were securely-placed in breast pockets for physical and spiritual protection.216

After finally getting word from Longstreet, McLaws belatedly dispatched his able aide-de-camp from one of Georgia’s leading families, Captain Gazaway Bugg Lamar, Jr., to order Barksdale to launch his long-awaited assault on the Peach Orchard. Dashing rapidly over the open fields, Captain Lamar rode a fine horse, which had cost him $500 in Confederate money earlier in the year. Here, before the shell-torn Pitzer’s Woods and the Mississippi Brigade’s ranks that stretched for several hundred yards from north to south, Captain Lamar galloped up to Barksdale, who was mounted before the 13th Mississippi, his own former regiment that he had first led into battle at First Manassas. Here, on the left-center of the Mississippi Brigade’s line, Captain Lamar recalled how “anxious General Barksdale was to attack the enemy, and his eagerness was participated in by all of his officers and men, and when I carried the order to advance, his face was radiant with joy. He was in front of his brigade, his hat off, and his long white hair reminded me of ‘the white plume of Navarre’.”

Barksdale barked out for his troops of all four regiments to advance simultaneously over the stone wall in their front at the eastern edge of Pitzer’s Woods. Without the usual clattering of gear and accouterments that had been piled behind them, the Mississippi Rebels climbed over the wall that ran along the eastern edge of the timber. With the almost unbearable tension of waiting having broken, they passed out of Pitzer’s Woods and into the bright sunlight of the open field.

As usual Barksdale took center stage before his elite brigade as one of the most stirring dramas of Gettysburg was about to unfold. One Mississippian long remembered “General Barksdale’s appearance, riding rapidly along in rear of the line, was the signal to the respective regimental commanders to get alert.” Barksdale galloped a short distance south from the 13th Mississippi’s front to the brigade’s center. With all eyes focused on him, Barksdale drew his saber, simply disregarding the obvious fact that he was thus about to become the most prominent target in the assault.

In a booming voice Barksdale yelled for all to hear: “The entrenchment 500 yards in front of you, and that Red Barn and that park of artillery [must be taken and] there is another 200 yards beyond which we are also expected to take. This is a heroic undertaking and most of us will bite the dust making this effort. Now if there is a man here that feels this is too much for you, just step two paces to the front and I will excuse him.” No man stepped forward from the double ranks of gray and butternut.

Within the next couple of hours, the Civil War could be decided once and for all by the upcoming clash at the Peach Orchard and in the open fields beyond that stretched toward Cemetery Ridge. As the culminating blow in Longstreet’s offensive against the Union left, it was Barksdale’s charge more than any other that would reap the fruits of victory, or else signal the failure of Confederate strategy. Never again would the Army of Northern Virginia meet the Army of Potomac on such equal terms, in an open-field battle on Northern soil, where the impact of a decisive victory for the South could decide the entire war. Much now depended on Barksdale and his men, and they were eager to meet the challenge.

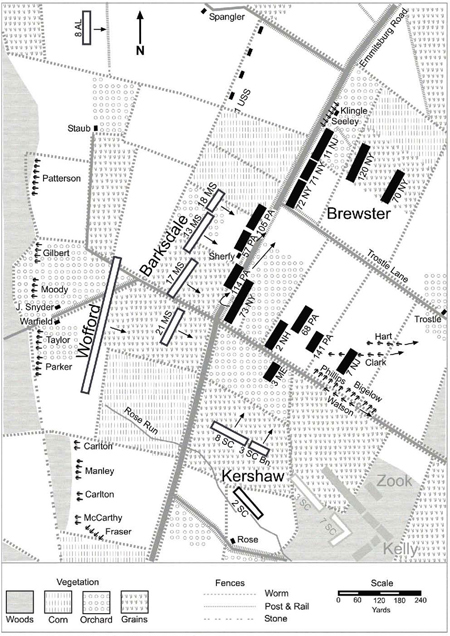

Map courtesy of Bradley M. Gottfried