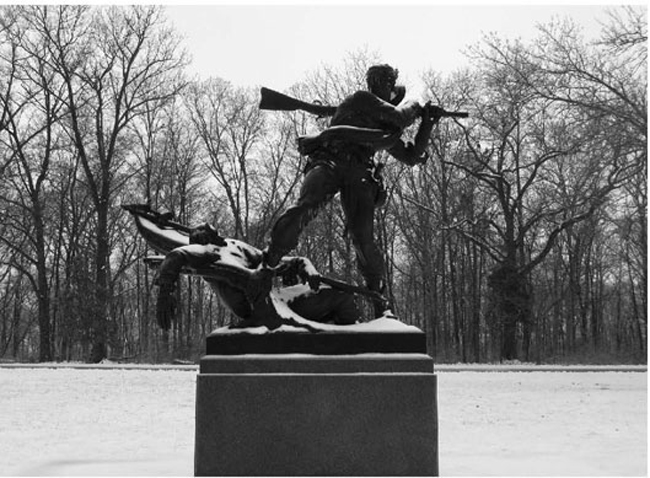

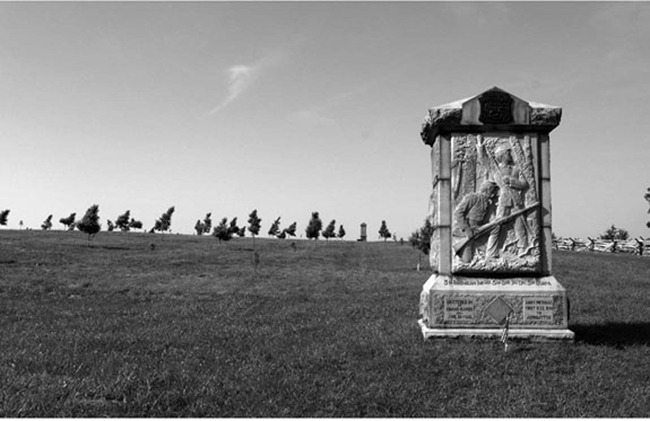

“The grandest charge ever seen by mortal man!”

LIKE BARKSDALE’S MEN, the Union soldiers holding the Peach Orchard salient had listened to the swelling tumult of battle approaching from the south. They knew their turn was coming, and as a long line of Confederates stepped out of the woods to their direct front they realized it was at hand. The men holding the salient were the First Brigade of the First Division, Third Corps, under Brigadier General Charles Graham. They were six regiments of Pennsylvania troops, who for the first time in the war were defending their home state instead of trying to invade another below the Mason-Dixon Line. Never more highly motivated than today, they yet had no way of knowing that their opponents, now in sight, were the Army of Northern Virginia’s Mississippi Brigade, men whose own home state was just then likewise being invaded, by Grant, in this most tragic and costly of American wars.

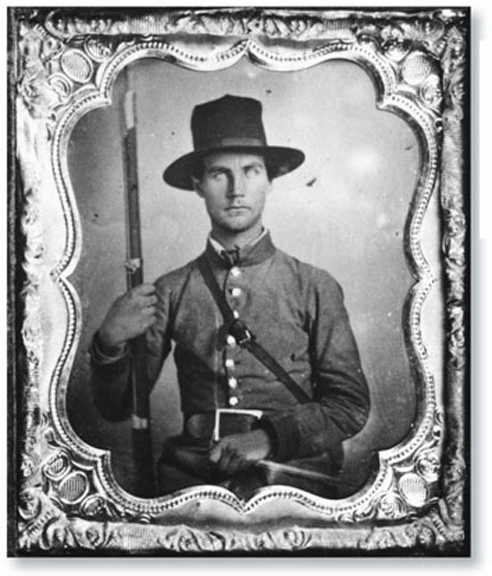

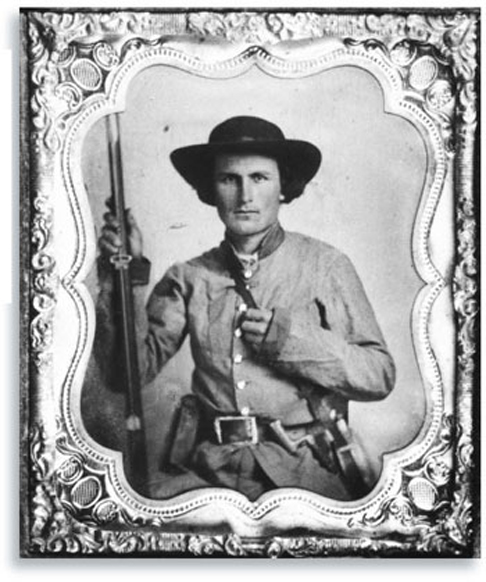

The Pennsylvania boys gave quick final checks to their rifles, then leveled them against the assembling Rebel host, still some 600 yards away. To fire too soon would be wasting a shot, then having to reload while the onslaught was nearly upon them. Fingers tensed on triggers and eyes squinted at the tree line as officers stalked up and down demanding, against natural instinct, for the men to hold their fire until ordered. Artillerists, who heretofore had been firing shell, now piled up their supplies of canister to fire like gigantic buckshot against oncoming infantry.

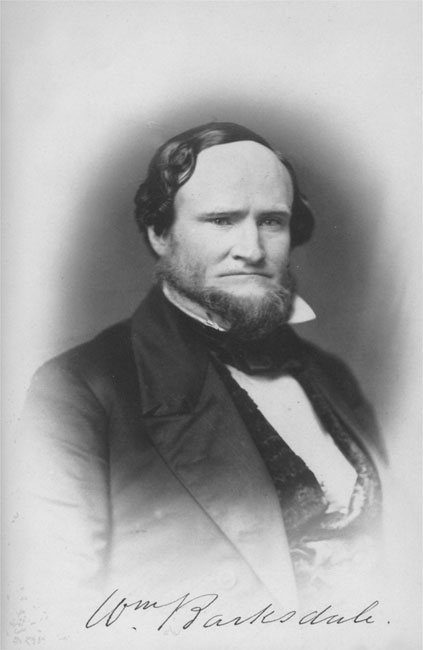

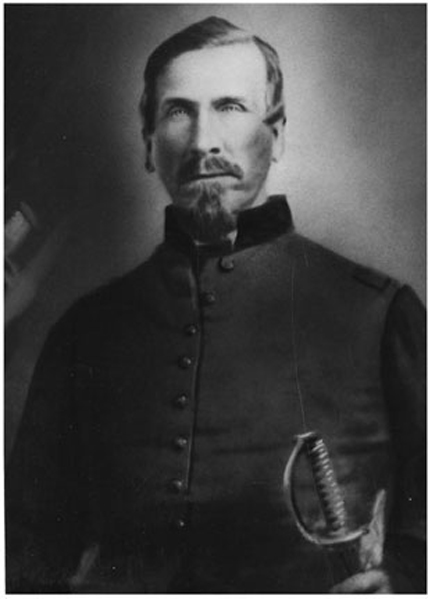

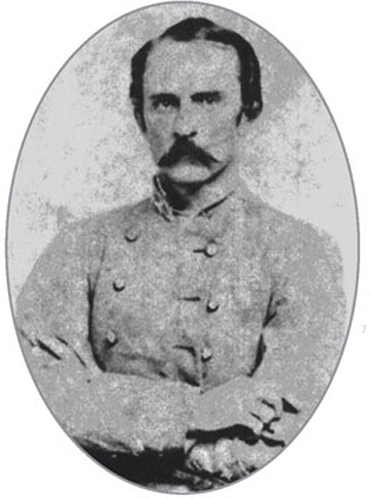

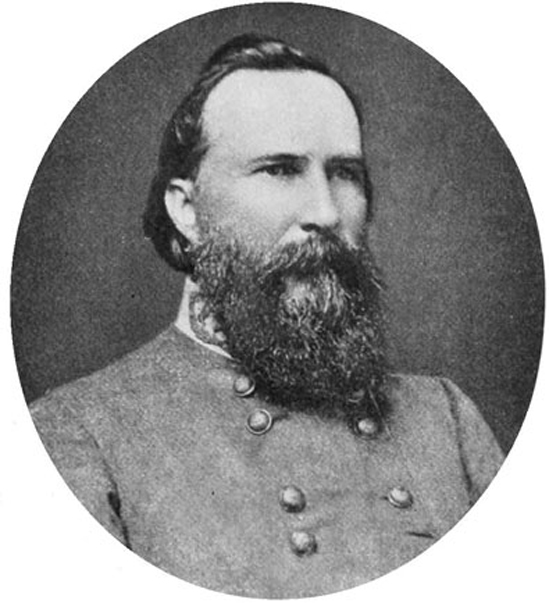

On the other side, at the fringe of Pitzer’s Woods, and before his lengthy formations of veterans standing at attention and not moving a muscle, “General Barksdale gave the word, and, waving his hat, led the line forward himself and we all followed him,” recalled one Confederate who never forgot the moment. As the heightened tension seemed about to burst, sharp orders rang out to “dress to the colors and forward to the foe!” With more determination to reap a decisive victory than ever before, some 1,600 men of the Mississippi Brigade surged ahead in two lengthy, parallel lines that stretched across the bright green field. To encourage his troops onward over the open ground and down the gentle eastern slope of Seminary Ridge, Barksdale continued to shout and wave his saber, imploring “Forward, men, forward!”

Captain Harris Barksdale, diminutive but every-inch a fighter, never forgot the moment when “Gen. Barksdale rode to the center of his Brigade, and in a firm voice gave the command, ’Attention, Mississippians! Battalions Forward!’ … and the line officers repeated the command ’Forward, March’.” Along a 350-yard front spanning Seminary Ridge’s eastern slope, Barksdale’s assault waves surged across the open fields of summer with red battle-flags waving.

From the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, one bluecoat described how General “Barksdale and his Brigade had to pass over a mile of open field [sic] to get to us … while he was forming his men in line of battle, the missiles from the [artillery] plowed gaps through his men, yet in battle line they stood [and prepared] to traverse the mile of open field intervening [and] when our sharp-shooters and the pickets opened fire on [and] besides the mischief done by the sharp-shooters and pickets, the [artillery] was hurling missiles of death into ranks …” Watching in awe at the Mississippians’ disciplined surge down Seminary Ridge, Long-street remembered when his high-spirited Magnolia State brigadier went into action “with glorious bearing.”217 And an Alabama soldier never forgot how the stirring sight of the Mississippians’ assault was “grand beyond description.”218

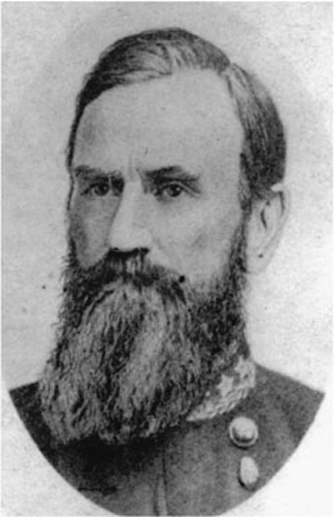

To the steady thud of beating drums and the shrill of fifes played by young, beardless musicians in gray, no regiment advanced in Barksdale’s long line with more firmness of step and resolution than the 21st Mississippi. On the brigade’s right and serving as a steady anchor for Barksdale’s assault, Colonel Humphreys described how, “the men sprang forward and sixteen hundred voices raised the famous ‘Rebel yell’ which told the next brigade, Wilcox’s Alabamians, that the Mississippians were in motion.”219

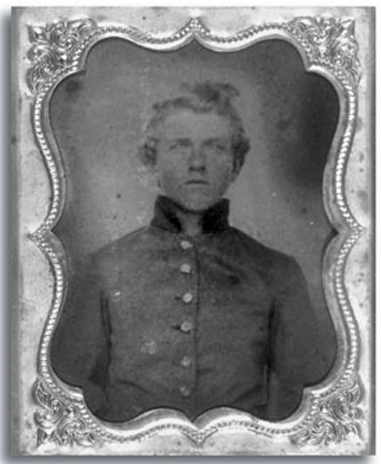

To the 21st Mississippi’s left, Private Judge D. Woodruff, Winston Guards of the 13th Mississippi, described the panoramic, wide-open arena that lay before him: “The field was clover and a gradual slope up to where the Yankee lines and batteries were about six hundred yards away.”220 Meanwhile, Mississippi drummer boys, who should have been in school, continued to beat their drums in a steady cadence as if leading a Sunday parade in Jackson rather than into the maelstrom, until it seemed that their instruments would certainly burst. Archibald H. Christy, an eighteen-year-old from Holly Springs, of Company B, 17th Mississippi, was one such musician. Despite having already been wounded at First Manassas and at Fredericksburg, Christy was now advancing in the front ranks, even though he knew would receive the brunt of the Yankees’ fire.221

By now the row of Federal guns, Bucklyn’s lethal Rhode Island pieces and a section of Thompson’s Pennsylvania Battery, that represented Pittsburgh, roared from the high ground along the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, hurling shells that smashed into the Mississippi Brigade’s ranks. One Federal defender of the Peach Orchard described how the intense concentration of artillery fire “swept gaps through them all the way across the field, and when a solid shot tore a gap in their ranks, it was instantly closed up, and the Brigade came on in almost perfect line.” Most of all, these Mississippi infantrymen felt the inspiration from what Barksdale had yelled to them just before he launched his winner-take-all attack upon the Peach Orchard: “We have never been whipped and we never can be.”222

The expert Union gunners blasted away at the lines on the open ground that could hardly be missed. Private John Saunders Henley, 17th Mississippi, described how “all their artillery [was] firing on us [but] We went in perfect line. They would knock great gaps in our line.”223 Barks-dale’s neatly aligned formations pushed stolidly forward with a well-honed steadiness that told the Yankees on the high ground that hardened veterans from the South were descending upon them in a hurry. Keeping on the move, the Mississippi Rebels ignored the exploding shells that knocked down an ever-increasing number of comrades. Clearly, the dividends of Barksdale’s longtime, seemingly obsessive focus on the importance of drill was now displayed in splendid fashion across the fields that stretched all the way to the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Neither Union artillery fire nor the brisk firing of bluecoat skirmishers, banging away angrily and effectively, disrupted the flow of Barksdale’s advance.

Most of all knowing that his troops had to reach the Emmitsburg Road Ridge as soon as possible to avoid being shot to pieces during a methodical, textbook-like advance, Barksdale ordered his men to double-quick when yet far from their objective. Unleashing the high-pitched “Rebel Yell,” to both “inspire and terrorize,” the Mississippi soldiers raced on toward the smoke-wreathed Peach Orchard and Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Now finally unleashed with flashing bayonets that sparkled in the summer sunlight, the Mississippi soldiers neared the slight swale, located roughly halfway between Seminary Ridge and the Emmitsburg Road Ridge.

On the brigade’s right, Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi, never forgot when Colonel Humphreys gave “the ringing command-‘Double quick, Charge,’ and at top speed, yelling at the tops of their voices, without firing a shot, the brigade sped swiftly across the field and literally rushed the goal [and] our men began to drop as soon as they came to attention, and were well peppered in covering the distance with the enemy.” On the double, Barksdale’s lines poured through the fields without breaking ranks, even when exploding shells blew holes in formations. All the while, the powder-grimed Confederate gunners cheered the Mississippians’ attack by waving hats. These sweating artillerymen, shouting their lungs out, wanted Barksdale’s boys to exact bloody revenge on those lethal Union cannon, which had outmatched the inferior Rebel guns. With battle-flags flapping, Barksdale’s onrushing ranks neared the depression about mid-way between Seminary Ridge and the Emmitsburg Road.

The Mississippi veterans now felt a surge of new invigoration by having been finally “unleashed at last and eager to come to grips” with the Yankees. Leading the 21st Mississippi onward, Humphreys described how everyone “moved forward, amid the roar of cannon and the rattle of rifles [and] the work of death” was cruelly relentless to Barksdale’s attackers.224 In the 17th Mississippi’s ranks, Private John Saunders Henley described the ever-escalating momentum that could not be stopped after the “regiment began to run” toward the high ground.225

Inspiring the soldiers onward in the first rank of gray and butternut waved the brightly colored battle-flags, while Barksdale’s four regiments, the 18th, 13th, 17th, and 21st Mississippi, from left to right, surged onward. One emblem now flapping at the head of this charge was the silk banner of Company K, 18th Mississippi, which had been sewn by wives, daughters, mothers, and sisters of home communities. Presented to Company K by Miss Alice Hilzm, the Burt Rifles’ battle-flag was decorated with a colorful painting of a full blooming Magnolia tree that represented their state. The Burt Rifles’ banner contrasted with the standard Confederate battle-flags featuring a star-bedecked St. Andrews Cross.226

Due to tactical developments to the south, Barksdale’s Brigade was charging alone, without connection to any units on its right, nor yet on its left. John Bell Hood’s division, more fresh and ferocious on this day than most in the Army of Northern Virginia—for having missed Chan-cellorsville, much to its commander’s dismay—had drawn upon itself the entire Union Fifth Corps, as well as a division of the Second Corps, in addition to the troops of the Third Corps it had first attacked. In addition, part of the division had been compelled to attack up the steep citadel of Little Round Top, over unspeakable terrain that broke up formations by itself. As Federal reinforcements piled into the sector, Kershaw’s Brigade of McLaws’ Division, followed by Semmes’, had gone in to retrieve the situation. But by now the Union Sixth Corps had arrived on the field, also ready to resist the continued onslaught against the Federal left. As Hood had predicted, his attack could not succeed except at high cost. However, as Longstreet may have perceived, his initial assault had sucked in so much of Meade’s strength on his far flank that an opportunity was now presented to make the true breakthrough at the Union left-center. Not by “attacking up the Emmitsburg Road,” as Lee had mistakenly envisioned, but by striking due east, onto ground which by now had been denuded of troops save the forward array around the Peach Orchard. If that salient could be crushed, there was little behind it to prevent a breakthrough of the Federal line.

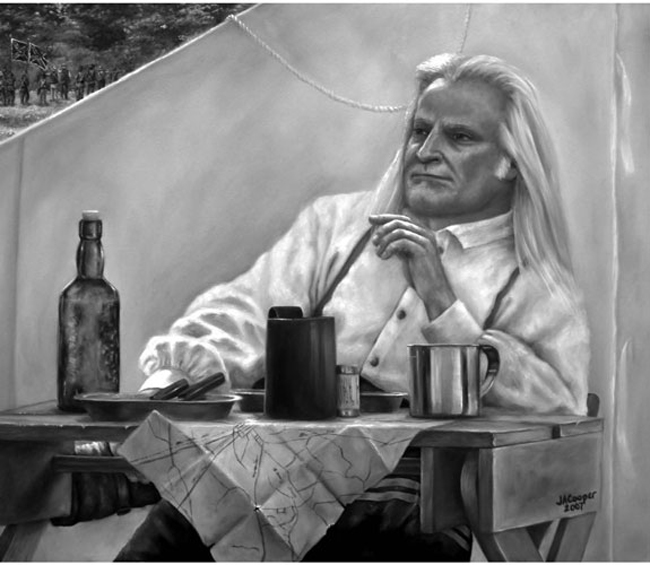

If one examines Longstreet’s offensive actions throughout the war, it’s clear that he always preferred the “one-two punch.” The classic example is Second Manassas, when Stonewall Jackson held the Union army for over a day, then Longstreet delivered the knock-out blow. This technique was perfected at Chickamauga where Polk struck first, drawing in Union reinforcements, and then Longstreet launched a gigantic battering ram that obliterated Rosecrans’ entire right wing. At the Wilderness the following spring, Longstreet arrived last on the field after Ewell and A.P. Hill had held off the Federals for a day, but then the arrival of his corps turned the tide completely, facing Grant with catastrophe in his first battle in the east, until Longstreet himself fell wounded and thus the Confederate effort dissipated.

At Gettysburg, Longstreet much rued the fact that the Confederate Second Corps was so far-flung that it could be of no help to him. In the new Third Corps he had little faith, and it had been largely used up on the first day of the fight, except for Anderson’s Division, which had formerly been under his command and would now assist. He primarily had to devise a one-two punch with his own two divisions, but that is what he essentially did. Naturally he would have preferred Hood to drive in the enemy flank before he launched McLaws. However, if Hood only succeeded in drawing the weight of Union countermeasures on himself, Longstreet could wait, and wait longer, till he saw Meade was committed. Despite Barksdale’s eagerness, he held back the Mississippi Brigade until he was certain that Meade had poured his available reinforcements into supporting his flank. Then he finally launched Barksdale against Meade’s left-center. If Barksdale could only crack the Peach Orchard salient, there would be an opportunity to sever the Federals’ entire left wing.

Meantime, Kershaw’s South Carolinians had run into trouble during the minutes before Barksdale’s launch. When Kershaw’s left wing, below and within 300 yards of the southern edge of the Peach Orchard’s salient angle, pushed northeast toward the Wheatfield Road sector, nearly perpendicular to Barksdale’s impending advance, a row of Union cannon along the road raked Kershaw’s left wing with blasts of canister, enfilading the South Carolina line. So deadly was the Federal artillery fire and so heavy were Kershaw’s casualties that the left wing’s advance, closest to Barksdale, was thwarted. Those South Carolina soldiers not killed or wounded fell to the ground to escape the artillery salvos, especially the murderous fire from the fast-working guns of the 9th Massachusetts Battery. The Palmetto Staters on the left were in a killing zone that reaped a grim harvest amid the ripe yellows stalks of the Wheatfield, while Kershaw’s right continued to attack straight east against a hotly contested feature known as the Stony Hill.

Semmes was launched to support Kershaw, thus temporarily stabilizing that situation. Hood’s four brigades still battled mightily, including in their Quixotic task of conquering Little Round Top. After the war the 15th Alabama’s Colonel William Oates, foremost in the assault, said that even if the tired remnants of his infantry had succeeded in gaining the summit, they couldn’t have held it anyway. Clearly, the hopes of the battle now rested with Barksdale, if he could only break through Sickles’ forward salient.

All the while, Barksdale led his fast-moving troops ever-closer to the flaming Peach Orchard sector now clouded in the white haze of sulfurous smoke. Despite the lack of support to its left, right or rear, the Mississippi Brigade’s attack was now, according to Noah Trudeau, “a living definition of unstoppable.”227 On through the open fields charged the Mississippians with the abandon so characteristic of elite troops in such a key situation. Around the halfway point between the two parallel ridges, the long waves of Mississippi Rebels neared the rail fence. From the ridgetop named after the Lutheran Theological Seminary, Captain Lamar, of McLaws’ staff, watched the inspiring sight of Barksdale, who was leading his fast-moving Mississippians through the killing fields: “I saw him as far as the eye could follow, still ahead of his men, leading them on.”228 Before the Mississippi Brigade’s advance, the wooden fence posed no impediment. Barksdale’s formations packed a pent-up, natural force all of its own, after having seemingly gathered momentum with each yard passed by the surging ranks.

In the rush to reach the smoke-laced crest of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the Mississippi Rebels continued to push onward with the Rebel Yell and a determination to gain the high ground at any cost. A Union colonel from New England standing in the Emmitsburg Road sector swore that this “was the grandest charge that was ever seen by mortal man.” Indeed, the Federal officer described with astonishment how, “nothing we could do with pickets, sharp-shooters or with cannon seemed to confuse or halt Barksdale’s veterans … nothing daunted Barksdale and his men and nothing seemed to be in their way [for they] just came on, and on, and on …”229

Indeed, the initial blue line of skirmishers, which was almost dense enough to make Barksdale’s men believe it was the first Yankee line of battle, was swept aside. Yelling louder with the exhilarating sight of the flight of so many Federals, the Mississippi veterans continued to run as fast as possible, while they closed in on the Emmitsburg Road Ridge with a renewed cheer.230 Charging with the boys of Company A, the Buena Vista Rifles, Private John Saunders Henley described how 17th Mississippi soldiers surged ahead on the “run,” after Barksdale gave the word.231

Before being brushed aside by Barksdale’s furious onslaught, the line of 5th New Jersey and 63rd Pennsylvania skirmishers had initially fought back from behind the slight shelter of a fence, a few cedar trees and scattered underbrush around the small spring at the lowest point of the slight depression. As the Yankee skirmishers had discovered the hard way, Barksdale’s countless drills month after month now paid dividends for the attacking Mississippians. A soldier recalled how, “the Magnolia State brigade sped swiftly across the field and literally rushed the goal” of the Peach Orchard, while pushing the hard-hit Federal skirmishers steadily before them as if by a giant broom.

Ignoring the hailstorm of shells and bullets dropping more good men from the ranks, the Mississippi Brigade continued to surge onward. Exploding shells wrought destruction among Barksdale’s formations, but the gaps were quickly closed-up. Meanwhile, the swiftness of Missis-sippians’ assault waves was an awe-inspiring sight not only to other Confederates but also to the Yankees. From the high ground, Sickles’ men watched the iron discipline and near perfect alignment of onrushing Barksdale’s soldiers. Private George Clark, a soldier of General Cadmus M. Wilcox’s Alabama brigade to the Mississippi Brigade’s left-rear, realized beyond a doubt that Barksdale’s onslaught was “the most magnificent charge I witnessed during the war.” And Captain Lamar, McLaws’ faithful staff officer, described how, “I had witnessed many charges marked in every way by unflinching gallantry … but I never saw anything equal the dash and heroism of the Mississippians.”

Captain Fitzgerald Ross, an “Austrian to the core” and an erudite observer with Lee’s army, recorded how Barksdale’s sweeping charge across the wide open fields “was a glorious sight [for the men] went in with a will … there was no lagging behind, no spraining of ankles on the uneven ground, no stopping to help a wounded comrade.” Mounted on his reddish-colored charger and waving his saber amid the whizzing bullets and bursting shells, Barksdale was distinguishable to one and all by his shoulder-length, prematurely gray hair streaming over his shoulders. Barksdale also wore a bright red sash around his waist. One observer watched with a mixture of awe and admiration, estimating that Barksdale was now leading his screaming Mississippi troops some fifty yards before his surging ranks. Impressed by the martial spectacle, Lieutenant Owen of the Washington Artillery described how the Mississippians’ attack “was a glorious sight.”232 Yet another fence and Yankee line of advanced skirmishers was swept away “like chaff before the wind.”233 Lamar could hardly believe his eyes, because “I was anxious to see how they would get over and around. When they reached it the fence disappeared as if by magic, and the slaughter on the other side was terrible.”234

Meanwhile, the defenders of the Peach Orchard sector were not idle while the Mississippi Brigade surged toward them. Facing the Emmitsburg Road and in support behind Lieutenant John K. Bucklyn’s Battery E, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, situated along the road just below the Abraham Trostle Lane, Graham’s brigade was aligned in the open fields. Here, they made final preparations for meeting Barksdale’s onslaught. During the nerve-wracking wait, Yankee soldiers said final prayers, recalled the lessons of bayonet practice, and braced for Barks-dale’s tempest. With lengthy ranks covering a broad front along the Emmitsburg Road, the 68th Pennsylvania anchored the left flank just south of the Wheatfield Road, the 104th Pennsylvania held the left-center amid an oat field, the 57th Pennsylvania stood on the right-center, and the 105th Pennsylvania, known as the Wildcat Regiment, was poised on the right flank, up to the Abraham Trostle Lane.235

After the Confederate artillery bombardment of two hours ceased, a flurry of adroit tactical adjustments were made by Graham to meet the Mississippians’ assault.236 On the double to confront the howling tide, fresh companies of skirmishers of the 57th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry advanced to the west side of the Emmitsburg Road to take possession of a better defensive position and higher terrain from which to deal punishment upon the onrushing Mississippians. On the double, a good many expert marksmen in blue also hurriedly filed into the Sherfy House, an ideal elevated shooting platform perched on commanding ground. Here, they took firing positions at the narrow windows—perfect firing slits—overlooking the open fields now filled with howling Mississippians. Situated atop a little knoll, the Sherfy House offered not only shelter from Barksdale’s onslaught but also the most elevated spot to deliver punishment over a wide area.237

While rushing toward the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the Mississippi Rebels felt that not only the battle’s outcome but also the Confederacy’s life depended upon them. By this time, the furious Confederate assaults to the south at Little Round Top, the Devil’s Den, where one appalled Texas soldier described the bitter fighting that swirled savagely “around rocks as large as a meeting house,” and the golden stalks of the bodycovered Wheatfield of farmer George W. Rose, were meeting terrific resistance and sputtering from right to left. Despite Southern heroics and high sacrifices, all that was accomplished was a grim lengthening of casualty lists with each passing minute during what one horrified survivor called “a devil’s carnival.” The slaughter led to “Confusion [which] reigned supreme everywhere” on Lee’s battered right.238 William, “Bill,” A. Fletcher, a proud member of Hood’s hard-fighting Texas Brigade, la -mented over so many “true and tired men being shot down like dogs.”239 Consequently, as Confederate fortunes continued to flounder to the south, it was increasingly up to the Mississippi Brigade to smash through the Peach Orchard sector and reap a decisive success for the Army of Northern Virginia.240

Meanwhile, Federal defenders continued to be impressed by the grand spectacle of the Mississippians’ rush headlong into a murderous fire of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania artillery. The lithe and lean veterans kept surging ahead on the double without a pause. By this time, the Mississippi Rebels instinctively realized that their only chance for success called for getting across these broad, open fields of fire as rapidly as possible.241 Atop the Second Corps sector of Cemetery Ridge to the northeast, Captain Haskell described the dramatic showdown for possession of the Peach Orchard: “We see the long gray lines come sweeping down upon Sickles’ front …O, the din and the roar, and these thirty thousand [sic] Rebel wolf cries! What a hell is there down that valley!”242

Indeed, Barksdale’s ranks promised to pack a mighty punch and inflict devastation on the defenders in a wide swath, if the ridge could be swiftly reached.243 Barksdale’s headlong attack, in the words of Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi, was most of all a “matchless ‘rush to glory or the grave’.”244 Indeed, more than anything else, Barksdale’s all-or-nothing charge was now in essence a desperate bid to reach the commanding high ground, before too many men were cut down and the attack’s momentum was destroyed. In charging so swiftly up the gradually rising ground to the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the Mississippi Rebels were in the process of fulfilling Barksdale’s earlier bold promise to Longstreet that he could capture the most destructive Union battery—Lieutenant Bucklyn’s six Rhode Island guns—in only five minutes once unleashed. Such a tactic was in keeping with Colonel Humphreys’ conviction that his 21st Mississippi attackers were now “determined to break the line before them, or perish.”245

All the while, Barksdale remained in advance of his troops, leading the way before his surging ranks of gray and butternut. Mounted for all to see, he continued to wave his saber, as unornate and relatively plain as his uniform, while encouraging his boys onward. The commanding figure of the forty-two-year-old Barksdale served as a shining “beacon for his brigade” during one of the greatest charges of the war.246

To escape the 21st Mississippi’s onslaught upon the suddenly strategic Peach Orchard crossroads and salient angle, the 63rd Pennsylvania, which had screened Graham’s over-extended front as skirmishes, continued to head rearward on the double, after having expended its ammunition in attempting to kill as many Mississippi Rebels as possible. Captain Harris Barksdale never forgot how his charging Mississippians “sweep the enemy’s picket line before them like chaff before a whirlwind.”247 Meanwhile, the sight of the onrushing Mississippi Brigade caused defenders to lament the absence of trenches, earthworks, or even piles of fence rails. In the words of one soldier of the 57th Volunteer Infantry, “Unlike the battlefields of Virginia where we usually fought in the woods or thickets, we were now on a field where we had an unobstructed view” of the field of strife.248

A hot fire, meanwhile, poured from the second floor windows of the Sherfy House, with sharp-eyed Yankees blasting away at Barksdale’s attack lines on the open fields. Not only from the Sherfy House, 57th Pennsylvania skirmishers around the farm’s outbuildings and trees also maintained a heavy “fire on the enemy who were within easy range.”249 However, Barksdale still resisted the temptation to halt the ranks to return fire by volley. Most of all, Barksdale knew that he had to get his troops across these open killing fields as quickly as possible. Like his comrades, therefore, a 57th Pennsylvania soldier was greatly surprised by the fact that the Mississippians “did not reply to our fire.”250

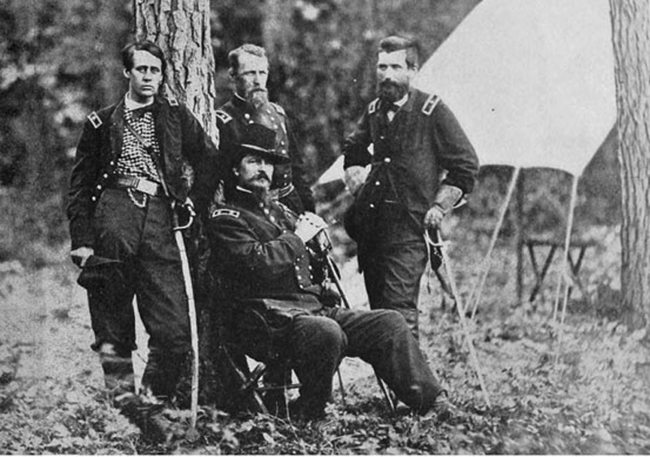

The reliable veterans of Graham’s 1,516-man brigade, with their plentiful artillery, held firm at the Peach Orchard salient and the high ground along the Emittsburg Ridge Road. The line bent at a right angle where it met the Wheatfield Road, where stood the 68th Pennsylvania under Colonel Andrew H. Tippin. No ordinary officer, Tippin was a revered hero of the Mexican War, having been the first American soldier to gain the Mexican defenses during the bloody assault at Molino de Rey outside Mexico City, on September 8, 1847. When Barksdale’s attack began, the 68th Pennsylvania’s was brought up to the Emmitsburg Road south of its junction with the Wheatfield Road, directly across from the Peach Orchard’s rows of fruit trees. To meet Barksdale’s onslaught, Graham’s four veteran Pennsylvania regiments, bolstered by Bucklyn’s Rhode Island guns and Thompson’s section of Pennsylvania artillery, were aligned along the east side of the Emmitsburg Road, holding the strategic crest of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Belonging to General David Bell Birney’s First Division of Sickles’ Corps, these reliable Pennsylvanians proudly wore their red diamond corps badges on blue kepis with a jaunty air, feeling a great deal of pride in themselves and their hard-fighting units.

Bracing for the Mississippians’ impact, the 57th Pennsylvania was led by a most capable commander. Colonel Peter Sides had demonstrated skill that had elevated him to lieutenant colonel from a captain’s rank back in mid-September 1862. In the war’s early days of innocence and as if yet on the farm, these Pennsylvania men had called their commanding officer “Charley” instead of colonel. But now the 57th Pennsylvania boys were tough, disciplined soldiers. Its Company K included a number of Native Americans from the once-mighty Iroquois nation. Their names, such as Levi Turkey Williams and Wooster King, reflected a distinctive Native American culture that had failed to sufficiently distance them from the ugly realities of the white man’s civil war. These mostly Seneca warriors from New York’s Allegheny Indian Reservation proved worthy of their tribe’s warrior heritage during Gettysburg’s inferno.

Even after the 57th Pennsylvania’s strength had been reduced by onefourth by the brutal ravages of bloody battles and epidemics of deadly disease, the mettle of these high-spirited men was evident when they had nearly mutinied upon receiving orders to consolidate with another unit. Like Washington’s Pennsylvania Line Continentals who mutinied in early 1781 and marched in protest on Philadelphia during America’s struggle for liberty, these boys in bue had threatened to march on Harrisburg under arms in protest. Ironically, the 57th Pennsylvania’s baptismal fire had been received on the Virginia Peninsula at the “battle of the Peach Orchard,” at Williamsburg, Virginia. And as a strange fate would have it, the 57th Pennsylvania had been positioned on the high ground at Malvern Hill when the Mississippi Brigade attacked. Then, before the year’s end, the Keystone State regiment lost more than half of its strength, including its regimental surgeon, during the suicidal attack on Freder-icksburg’s heights. And in early May 1863, another 30 percent casualties were suffered by the 57th in Chancellorsville’s dank woodlands, leaving only a relatively small-sized regiment for the showdown at the Peach Orchard.251

Nevertheless, Colonel Sides now led a well-disciplined regiment, armed mostly with .54 caliber Austrian rifled muskets. Promising to give Barksdale’s men a tough fight, the 57th had won the hard-earned reputation for reliability. These hardy soldiers now defended the northern arm of the Peach Orchard salient along the Emmitsburg Road around the Sherfy House. They were yet motivated by an inspirational example that was now part of their unit identity: their respected former commander, General Philip Kearny, whose “pet” regiment was the 57th, who had been killed at Chantilly, Virginia on September 1, 1862. Grieving 57th Pennsylvania soldiers had served as the special honorary escort that took the body of the revered Mexican-American War hero to Washington, D.C.

The 57th Pennsylvania had been under fire from Colonel Alexander’s artillery for two long hours. However, they had suffered relatively little damage. Consequently and despite having been initially positioned in the open fields on the Emmitsburg Ridge Road’s east side without shelter during the intense cannonade, the 57th Pennsylvania troops were in overall good shape. Most Rebel shells had whizzed harmlessly over the prone Pennsylvanians to explode in the open fields behind them, destroying Farmer Sherfy’s well-nurtured crops instead of Yankees. Federal infantry positioned near the targeted cannon suffered more than any others, but the overall damage inflicted on both infantry and artillery was insufficient. Even the 114th Pennsylvania, in support of Bucklyn’s Rhode Island guns, was relatively unscathed from Alexander’s bombardment.

Consequently, everything now depended on the Mississippi Brigade’s fighting prowess to punch a hole through the Peach Orchard defensive sector by the standard tactics that had long ensured bloody failure in this war: a frontal assault with the bayonet launched against a high ground defensive position held by large numbers of veterans and artillery.252 And defenders like the 57th Pennsylvania had earned the reputation as “men that won’t run.”253

To the 57th Pennsylvania’s left and deployed along the Emmitsburg Road to protect the six guns of the First Rhode Island Artillery stood the 114th Pennsylvania. Bucklyn’s six guns stood defiantly in the 150-yard open space of high ground situated between the Sherfy House and the John Wentz buildings just to the southeast and immediately north of the Wheatfield Road. While the battery’s left and center sections blasted away from good high ground firing positions between the Wentz House and the Sherfy barn, the right section fired at the attacking 18th Mississippi from a dominant, elevated position in the garden near the Sherfy House.

Holding the line near and immediately south of the Sherfy barn to protect Bucklyn’s booming guns, the 114th Pennsylvania was yet another fine regiment of Graham’s Pennsylvania brigade. Symbolically providing an indication of the close relationship existing between Union artillery and infantry, because each depended so much upon the other for mutual survival against attacking Rebels, these Pennsylvania infantrymen had rescued Captain Randolph’s guns at Fredericksburg. The memory of that timely intervention now set the stage for a comparable timely support role of these Pennsylvania infantrymen, who had been specifically chosen by Graham to support the Peach Orchard batteries.254

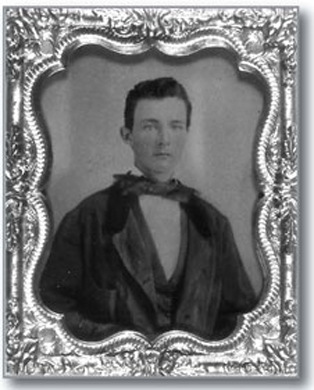

The 114th Pennsylvania was known collectively as Collis’ Zouaves. These Philadelphians were named for the unit’s former commander, a feisty Irish immigrant who migrated to America in 1853 and became a successful Philadelphia attorney, Colonel Charles Henry Tuckey Collis. He had been born in the busy port of Cork, nestled amid the green rolling hills of southern Ireland. Although diminutive, the handsome Irishman was pugnacious, and Collis bestowed this combativeness to his fine regiment. Consisting of enlisted members with an average age of twenty-four but also including a good many eighteen-year-olds, this Zouave Pennsylvania regiment had demonstrated its worth at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, where the command suffered a high percentage of loss. During its baptismal fire at Fredericksburg and after snatching the regimental colors from a dismayed flag-bearer, Colonel Collis had led a fierce counterattack to push the Rebels back, saving Captain Randolph’s Rhode Island battery and two other batteries from capture. The Irish colonel won a Congressional Medal of Honor for valor.

The 114th Pennsylvania now once again supported the New England gunners of the Rhode Island Light Artillery in yet another, but much more important, dramatic showdown. These colorfully attired 114th Pennsylvania Zouaves were mostly city boys from Philadelphia—clerks, laborers, shoemakers, and carpenters, in contrast to the mostly yeomen farmers of Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade. Fancy Zouaves d’ Afrique uniforms were modeled after those worn by French soldiers, who had fought the fierce North African Berber tribesmen of Algeria, which had been first occupied by a colony-hungry France in 1830.255

Ironically, Collis, when a captain, and his initial command of Zouaves, an independent company known as the Zouaves d’Afrique, had nearly met Barksdale’s men at Ball’s Bluff, but they had remained in a support role when the isolated Union task force was crushed. Unfortunately for Collis’ Zouaves this afternoon, the thoroughly seasoned Mississippians were now far more lethal than in October 1861.256 Ever-mindful of their distinctiveness compared to the other “Blue Legs” in regulation uniforms, these jaunty Pennsylvania Zouaves referred to themselves as “Red Boys,” “Zoo Zoos” and the “Zoos.”257

An awed private of another Union regiment described Collis’ highspirited Zouaves in a most revealing letter: “they are beauties I tell you— but when they ’Charge bayonets’ with such a yell as Zouaves only can give, the rebels’ll skedaddle even if the greybacks have five times as many men as the red breeches have.” The Pennsylvania Zouaves’ reputation for hard fighting had preceded them, because the Rebels said “that they didn’t like to fight the Red Legs [because] they say we look like Devils and fight too hard [and] they say we try our best to kill and I think they are about right.” However, Barksdale and his Mississippi Rebels were about to destroy this myth and erode the regiment’s lofty reputation.258

No longer led by the dapper, 115-pound Colonel Collis, who was on leave, this Keystone State regiment of highly motivated Zouaves was now commanded by Cuban-born Lieutenant Colonel Frederic Fernandez Cavada. Cavada was a classic example of the forgotten Civil War among Latinos, or Hispanics, including Cubans who wore both blue and gray. Symbolizing the deep pre-English roots in America, more than 20,000 Hispanics fought on both sides. And the showdown at Gettysburg was no exception, with Latino Rebels serving mostly in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida regiments. Explaining motivations, Confederate Tejano Captain Joseph Rafael de la Garza, who died in battle in 1864, was “fighting for our country,” in his words from a letter.

Educated at an excellent school in Philadelphia, Cavada was a romantic, liberty-loving poet, the product of a Cuban father and American mother. His slave-owning family had departed Cuba when he was young, migrating to Philadelphia. A fiery Cuban nationalist, Cavada hated the autocratic rule of Spain, which governed its wealth-producing Caribbean colony with an iron hand. Lieutenant Colonel Cavada now commanded the Zouave regiment despite suffering from recurring bouts of malaria. He had acquired the deadly tropical disease when surveying a railroad line through the tropical jungles of the Isthmus of Panama. The enlightened Cuban had also served as an army engineer and on the personal staff of Major General Birney, a Philadelphia attorney who had commanded his own Zouave regiment (Twenty-third Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry) early in the war.

In his own personal crusade to destroy slavery in a struggle that was “the cause of all humanity,” handsome Lieutenant Colonel Frederic Cavada, dark-haired and with black eyes, took command of the regiment at Chancellorsville after Colonel Collis became ill. Because of politics and anti-Latino and anti-Catholic sentiment, the easy-going Cuban faced unfair charges for his role at Fredericksburg. Knowing of Cavada’s love of liberty, President Lincoln, remitted the court martial’s unfair sentence, however. Lieutenant Colonel Cavada then took command of the Zouave regiment, eager to redeem his reputation and demonstrate the worth of his well-training fighting men.

Meanwhile, along with the 57th Pennsylvania, the 114th Pennsylvania began to advance west of the Emmitsburg Road in order to protect Bucklyn’s guns. A 114th Pennsylvania soldier described how the Zouave command advanced to the west side of the road “with alacrity and passed through and to the front of the battery.” However, these sturdy Pennsylvania blue-clads gained a more advanced position not on orders of General Graham. Instead, the Pennsylvanian’s advance across the Emmitsburg Road was born of desperation. A desperate Captain George E. Randolph, chief of the Third Corps’ artillery brigade and although wounded in the shoulder by a Mississippi skirmisher’s bullet, had ridden up to the Pennsylvanians and implored: “You boys saved this battery once before at Fredericksburg, and if you will do it again, move forward!”

Positioned on the open ridge before the Pennsylvania Brigade, Bucklyn’s Rhode Island cannoneers had suffered more damage from Alexander’s artillery fire than the infantrymen. Private Ernest Simpson was one of the battery’s early losses. He was a young, heartsick man who had lost the will to live because of a recent letter from his strict, God-fearing parents. They had refused to approve his marriage to a pretty girl of questionable reputation. Instead of remaining safely in the rear as usual as the battery’s clerk, the tortured New England gunner overly-exposed himself at the front, where he was decapitated by a shell, to his comrade’s horror but perhaps to his own relief.

Taking full responsibility for the spontaneous decision to advance the Pennsylvania Zouaves, as if taking a cue from Sickles’ own decision to shift the entire Third Corps so far before the main line without Meade’s consent or knowledge, Captain Randolph exercised independent thought and tactical flexibility. After having been unable to locate General Graham, Randolph acted on his own, displaying the kind of bold initiative that was now necessary for any hope of stopping the hardcharging Mississippi Brigade.

Without hesitation, therefore, he had ordered the Pennsylvanians forward out of a sense of desperation in an attempt to save his battery during the emergency, when the Mississippi Brigade was about to descend upon Bucklyn’s guns. Sections of the rail fences along the Emmitsburg Road had been torn down earlier by the Yankees in preparation for just such an emergency. The removal of these obstacles facilitated the lastminute movement of the two Pennsylvania regiments across the Emmitsburg Road to protect the artillery; however, the partial dismantling of the fences on both sides of the road shortly worked likewise to the Mis-sissippians’ advantage. After knocking down more of the fence and advancing, the 114th Pennsylvania hurriedly reformed across the open stretch of high ground west of the road. Why no Federals utilized any rails for defensive purposes has remained a mystery.

Nearly 400 soldiers of the 114th Pennsylvania now presented the most colorful sight on any battlefield yet seen by the Mississippians. These men wore their distinctive brass belt buckles, marked: “114 REGT. Z.D’ A. P.V” along with their fezes and fine red leggings. However, their appearance did nothing to awe the ill-clothed Mississippians, in their homespun garb. Instead, these colorful Zouave uniforms, described as “oriental,” would only draw a greater concentration of Mississippi bullets like magnets this afternoon. As if hunting game in the shadowy woodlands back home, the Mississippi boys relished nothing more than the opportunity to thoroughly punish these gaudy Yankees in their circuslike uniforms. But the Zouave’s fighting qualities could not be gauged alone by its outlandish uniforms. The 114th Pennsylvania, explained one soldier, was “as well-drilled and disciplined, as efficient and as brave a regiment as there was in the” army.259

At Chancellorsville, Graham’s brigade had launched a counterattack that stemmed the tide after the Eleventh Corps’ collapse after Stonewall Jackson’s flank attack. However, through no fault of their own, they then had been driven back in confusion during the bitter fighting around the Chancellor House. More than 400 Zouaves of the 114th Pennsylvania went into battle and 180 men were cut down. Fortunately for Barksdale’s Mississippi Rebels at this time, the Pennsylvania troops had not sufficient time to fully recover from the beating that they had suffered in Chancellorsville’s haunted forests, and now numbered only 259 men.260

As one 57th Pennsylvania bluecoat described the last-minute tactical adjustments when “the 57th and the 114th were ordered across the road where we beheld the enemy, which proved to be Barksdale’s Mississippi brigade, advancing through the fields toward us. Our regiment at once took advantage of the cover that the house, outbuildings and trees afforded and opened fire on the enemy who were within easy range, and did not reply to our fire …” Indeed, to the 57th Pennsylvania’s right and beyond, or north of the Sherfy House, the 105th Pennsylvania, whose right was aligned along the east-west running Abraham Trostle Lane and anchoring the right flank of Graham’s Keystone State brigade, also now advanced west of the road. Therefore, from left to right, the 114th, 57th, and 105th Pennsylvania Regiments were aligned in a lengthy formation stretching across the elevated area in the Sherfy House sector to meet Barksdale’s troops, who were drawing ever-closer with ear-splitting Rebel Yells. While the 105th Pennsylvania held an advanced position on commanding high ground just to the right of the Sherfy House, the 57th Pennsylvania aligned before the house and the 114th Pennsylvania occupied the ground between the house and barn farther south. From the commanding heights of the western edge of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the Pennsylvania soldiers now gained a full and chilling view of the onrushing Mississippi formations, whose sprawling length in double lines were marked by a good many bobbing battle-flags of bright red.

After he saw the dense blue formations of determined Philadelphia troops rising over the immediate open eastern horizon as if they had sprung from the earth’s bowels after they had advanced across the dusty road, Barksdale finally ordered his troops to unleash their first organized and concentrated volley of the day. The gray and butternut ranks exploded with an intense fire, and a sheet of flame ran down the line’s length. Barksdale’s primary target, Buckyln’s Rhode Island Battery, was cut to pieces, losing the highest number of casualties (nearly 30) than any other Third Corps Battery. Bucklyn’s horse was shot from under him. He was horrified to see that “My Battery is torn and shattered and my brave boys have gone never to return. Curse the Rebs.” And forty artillery horses were felled, making the removal of the hard-pressed Rhode Island guns more difficult in the crisis situation.

A solid sheet of musketry also thoroughly punished the Pennsylvania infantrymen for their audacity in advancing across the road. Because the 114th and 57th Pennsylvania had pushed forward with fixed bayonets to cover the inevitable withdrawal of the Rhode Island guns, this new high ground perch just west of the road only made them more vulnerable. In the words of Captain Edward R. Bowen, a wool merchant in his midtwenties from Philadelphia who eventually became the 114th Pennsylvania’s commander, the men advanced “to the Emmitsburg Road, in the face of the murderous musketry fire of the advancing enemy … reaching the road we clambered over the fence and crossed it [and moved on, while] Sherfy’s house and outbuildings intervening between us and the approaching enemy, the right of the regiment was advanced to the rear of the house. While advancing in this way our men were loading and firing as rapidly as possible, and several times pauses were made, notably as we stood on the Emmitsburg road, and corrected the alignment, which was broken by clambering over the fence. During all this time we were receiving a terrible musketry fire from the rapidly approaching enemy, and the men were falling by scores.”

The commander of Company F and a former Philadelphia saloon keeper, Captain Francis Fix, who stood beside his brother, Lieutenant Augustus, “Gus,” Fix, fell with a mortal wound, when a Mississippi bullet shattered his knee. All the while, the Pennsylvanians fired from good defensive positions across a slight, level ledge or plateau, which marked the open western edge of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Blasting away like well-trained veterans, Cavada’s 114th Pennsylvania poured a hot “fire out between the house and barn,” wrote Philadelphia-born diarist Sergeant Major Given, whose wife Anne Patton had sent him off to war with a kiss and the words, “Go and God be with you.”

Beloved by the men for his kind, generous nature, Lieutenant Colonel Cavada, who commanded the 114th Pennsylvania with skill this afternoon, had been earlier warned about Barksdale’s attack by Sergeant Major Given that “You [can] bet your life they are coming in full force.” Cavada attempted to stabilize his hard-hit ranks, providing inspired leadership, while the torrent of Mississippi bullets cut down Yankees in groups and made the sulfurous air sing. The Mississippians’ rolling volleys that were unleashed with a murderous accuracy caused severe damage among the finely uniformed Pennsylvania boys.

One such soldier falling to rise no more was a young Pennsylvania Quaker named Corporal Robert Kenderdine, an old Anglo-Saxon name. He had long dreaded just such a brutal “killing day” as this one in Adams County, Pennsylvania. Kenderdine had protected the beautiful regimental banner as one of the few surviving color guard members. Barksdale’s men were now so close that Sergeant Henry H. Snyder, amid the deafening noise, was shocked when he saw cheering Mississippi Rebels with fixed bayonets emerging through the dense layers of smoke, taking deliberate aim, and shooting down Corporal Kenderdine like expert hunters picking off a squirrel. But the Mississippi marksman who cut down Corporal Kenderdine, who had cast aside his Quaker pacifism to fight for his country, was almost immediately felled with a well-placed shot. Here, on this killing ground along the treeless western edge of the Emmittsburg Road Ridge, large numbers of Lieutenant Colonel Cavada’s men “were killed and wounded here in the oatfield and around Sherfy’s house and barn.”261

Meanwhile, the hard-pressed 114th Pennsylvania received some timely support when General Andrew Atchinson Humphreys, at Graham’s frantic request and Sickles’ immediate concurrence, ordered one of his favorite regiments, the 73rd New York Volunteer Infantry, known as the Second Fire Zouaves of the “Excelsior Brigade,” south from its unengaged position on his division’s left along the Emmitsburg Road.262 Having enlisted at age nineteen and destined to fall wounded during this tempestuous afternoon in hell, Lieutenant Frank E. Moran, a New York City painter who now commanded Company H, 73rd New York, described how “we moved toward the orchard at double-quick through a shower of bullets and bursting shells.”263

At this time, Moran, of Irish descent, wrote how, the “114th [Pennsylvania], stretched along the Emmetsburg [sic] road from the gate of the Sherfy house and past the barn, were hotly at work and sorely pressed [and] fearfully exposed on the crest which rises at that point, was gallantly disputing the ground with the Mississippians, who, [led] by Barksdale, came swarming up yelling like demons.”264 Meanwhile, after pushing south to the Sherfy House sector, the breathless New York soldiers, gasping for air in the intense heat, covered in sweat and dust, and coughing amid the drifting layers of smoke, aligned about thirty yards behind the 114th Pennsylvania. As fate would have it, the largest concentration of Zouaves on the Gettysburg battlefield now faced the Mississippians. After the 73rd New York troops formed “quickly in line, and the ’click, click’ of cocking muskets” rang through the sulfurous air,” alerting Barksdale’s attackers of another sweeping volley soon headed their way.265

One of the most fiery Cuban nationalists in America, like his lieutenant colonel brother Frederic, Lieutenant Adolfo Cavada, a respected member of General Humphrey’s staff, was concerned about his brother’s welfare now that he was caught in the path of Barksdale’s onslaught. He described how the “enemy’s fire slackened then came the rebel cheer sounding like a continuous yelp, nearer and nearer it came” to the Peach Orchard salient that was now at the vortex of the swirling storm.266 Meanwhile, Colonel Frederic Cavada ordered his men to stand firm and fire more rapidly.267 Colonel Cavada was determined to redeem the good name of all freedom-loving Cubans in blue, because so many of his native countrymen fought for the South. He yet lamented that these Cubans in gray had sacrificed “the broad principle of humanity to a narrow and pitiful geographic necessity,” and “I am proud of their scorn,” because he now wore the blue.268 Cavada’s regiment, along with the 57th Pennsylvania to its right, now bore the brunt of Barksdale’s attack, especially from Colonel Carter’s 13th and Colonel Griffin’s 18th Mississippi.269

Meanwhile, Barksdale had no idea that the 114th Pennsylvania Zouaves, aligned from the Sherfy House to just south of the Sherfy barn, were supported by the 73rd New York to their rear, and that his onrushing troops were about to plow into a double-line of veteran defenders.270

As ordered by Barksdale, his soldiers had actually launched their bayonet attack earlier than usual when first directed to double-quick over the open ground, but yet the firing from the ranks continued unabated by his veterans. By this time, these seasoned Mississippians were adept at the art of loading and firing on the run with a surprising degree of accuracy. Therefore, the 73rd New York was immediately greeted with a hot fire from Barksdale’s men, who suddenly emerged through the drifting smoke to shoot down a good many more Zouaves, as if this kind of slaughter was nothing more than sport. With the 114th Pennsylvania positioned to their front, the New Yorkers were unable to return a concentrated volley in reply.

By this time, the Rebels could not be stopped by the salvos of musketry and artillery vomiting forth from the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road sector. Some enterprising 57th Pennsylvania snipers, no doubt young farm boys, had even scaled cherry trees on the Sherfy property along the open ridge. These sharpshooters in blue blasted away from their lofty perches, including from the narrow windows, flanked by handcrafted wooden shutters, of the two-story Sherfy house poised on the high ground just west of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. This steady stream of punishment from above was described by one lucky Magnolia State survivor as simply “terrible.” Meanwhile, hundreds of veteran Union defenders continued to fire from the advantage of the high ground, blasting away as if there was no tomorrow. Delighted to be defending home soil, Private Joseph S. Beaumont, Company F, 57th Pennsylvania, yelled encouragement to his fast-firing men, “Give it to them boys, we have them on our own ground!”

All the while, Barksdale’s men continued to surge ahead with abandon, even though, as one of Colonel Humphreys’ men, Private McNeily described, “at points of the defense the enemy’s infantry was covered by stone fences and farm buildings [and] their deadliest fire was at such places.” Even the Pennsylvania Federals felt a growing admiration at the rather remarkable sight of a single Confederate brigade charging without support on either side or even support troops in the rear. The 57th Pennsylvania defenders positioned before the Sherfy House were perplexed by the unusual spectacle of an isolated Confederate infantry assaulting a high ground defensive position for “there were then no rebels to the left of those [which] engaged us, and for a while we had the best of the fight owing to our sheltered position.”271

With battle-flags flapping through the smoke, the Mississippi Rebels continued to charge toward the fire-spitting ridge around the Peach Orchard and the Sherfy House, while loading and firing as fast as they could on the run with the mechanical ease and drill-book precision of seasoned veterans. Making especially colorful targets along the high ground, the 114th Pennsylvania Zouaves continued to suffer heavily. They steadily fell in bunches to the Mississippians’ fire, especially that unleashed by Colonel Carter’s 13th Mississippi, which swept Cavada’s front with a close-range volley. More good Pennsylvania fighting men, such as Ser-geant Henry C. McCarty, Company K, who had won the Kearny Cross for past heroics, were fatally cut down in the hail of Mississippi bullets.272

The severe punishment delivered by the Mississippians’ fire-spitting rifles was too much to endure at such close range, and hard-hit Federals began to break for the rear. Private John Saunders Henley, 17th Mississippi, described how he and his comrades continued “firing on them, and they ran in crowds.”273 But despite the escalating losses, most of these tough Pennsylvanians held firm, especially in defending the slightly sunken roadbed of the Emmitsburg Road and firing from behind the post-and-rail fences alongside it. A member of the Buena Vista Rifles, Henley described how a “Pennsylvania regiment was posted behind an embarkment, and they killed lots of our boys.”274

Encouraging Company F’s soldiers of the Benton Rifles onward, Lieutenant William R. Oursler was one of those “boys” of Private Henley’s 17th Mississippi who was killed “near a Negro blacksmith shop near the Peach Orchard.”275 Ironically, Lieutenant Oursler, of German descent, received his death stroke on the land of a German farmer.276 But even more ironic, the son of John and Mary Wentz, whose log farmhouse stood just north of the crossroads in the Peach Orchard, now served in one of Alexander’s batteries, Captain Osmund B. Taylor’s Virginia Artillery, that had pounded the Peach Orchard.277

Not even the remaining double line of sturdy post-and-rail fences, lining both sides of the Emmitsburg Road, slowed down the Mississippians’ onslaught. Yelping their distinctive war-cry, Barksdale’s veterans, sensing victory, simply barreled over the wooden fences without stopping or halting to realign, as if they had long drilled for this most difficult of maneuvers. Captain Harris Barksdale described how “the first heavy line is encountered; one volley from their deadly rifles, and reloading as they rush on. Onward, still Onward! Vaulting over a rail fence they encountered the second heavy line of the enemy, consisting chiefly of artillery and of gaudily-dressed Zouaves. We drove them before us.” McLaws’ staff officer, Captain Lamar, penned that when the Mississippians swarmed over the fence “the slaughter of the ’red-breeched zouaves’ on the other side was terrible!” And Private Joseph Charles Lloyd, the Kemper Legion (Company C), 13th Mississippi, recorded the extent of the Mississippi Brigade’s success at this point, for “scarcely a minute and we were at the barn and scaling the fences at the lane and right across and in among the enemy, literally running over him.”278

The fleeing Pennsylvania Zouaves, jumbled-up and never so hard hit, presented ideal targets. Private Henley described the slaughter: “You could not shoot without hitting two or three of them,” with lead balls passing through stacked-up bodies like a knife cutting through butter.279 To the 57th Pennsylvania’s right, the 105th Pennsylvania troops, after having advanced up the slope to the west side of the road with the 114th Pennsylvania and the 57th Pennsylvania, also riddled the 18th Mississippi from the advantageous high ground.280 Representing the third, or main, line, the lengthy, blue formations of veterans of the three Pennsylvania regiments blasted away with a rapid fire, but they “were now alone in battling Barksdale’s men.”281 Rolling volleys cascaded down the open slope to rake the Mississippi Rebels, knocking down more attackers. A 114th Pennsylvania soldier described the Philadelphians’ stubbornness on the Emmitsburg Road Ridge’s western edge: “Standing on elevated ground, with open fields on all sides, the steady fire of the men, as the enemy’s infantry pushed forward, was delivered with excellent effect.”282

Just before pulling out in a hurry to escape Barksdale’s onslaught, the guns of Bucklyn’s battery, situated just south of the Sherfy House, continued to roar defiance into the Mississippians’ faces. Surging ahead with his Winston County comrades, Private Judge E. Woodruff, Winstson Guards (Company A), 13th Mississippi, described how, “The Yankee battery was on top of the rise where there was a dwelling house and barn and orchard. In back of them were … other cannon firing on us. It seemed as if you could hold up your hat and catch it full of grapeshot.”283

Entire swaths of 13th Mississippi attackers were cut down by artillery salvos. Manned by expert gunners, these fast-working New England cannon unleashed double loads of canister, the infantryman’s ultimate nightmare, at close range into the cresting waves of shouting Mississippi soldiers. The 57th Pennsylvania’s defenders not only possessed the advantage of occupying the dominant terrain just west of the Emmitsburg Road, but also the fast-firing “men of the 57th who were in the house kept up a steady fire from the west windows,” blasting away with abandon from both upstairs and downstairs.

Playing a role in leading the 21st Mississippi, which struck the 350-man 68th Pennsylvania, around the dusty crossroads that suddenly had become strategic, Captain Harris Barksdale continued to encourage the attackers onward across the body-strewn Emmitsburg Road. Colonel Humphreys’ veterans quickly formed a line with well-oiled precision to unleash a more concentrated volley, wreaking even greater havoc. Then, Humphreys’ furious attack continued up the slope and past the Emmitsburg Road, with the Mississippians “literally running over” a good many stunned 68th Pennsylvania bluecoats, who hardly knew what had hit them.

In a letter, Adjutant Harman, 13th Mississippi who was charging toward Bucklyn’s blazing Rhode Island guns, described when “the center of the Brigade struck the road at or near the 1st farm house on the Emmitsburg road to the north of Sherfy’s Peach Orchard. I crossed the road just to the south of the house.” Meanwhile, to the right, the fast-moving 21st Mississippi soldiers poured deeper into the Peach Orchard with wild shouts. Humphrey’s troops gained the Peach Orchard in less time—not much longer than five minutes—than what even Barksdale believed possible, when he had earlier boasted of that distinct, but seemingly unrealistic, possibility to Longstreet. Meantime, after observing Barksdale’s attack Longstreet later wrote, “With glorious bearing he sprang to his work, overriding obstacles and dangers. Without a pause to deliver a shot, he had the battery.”

Meanwhile, on the Mississippi Brigade’s left flank to the north, Barksdale’s elated 18th Mississippi soldiers surged “forward until both parties met at or near the old barn,” which now became the eye of the raging storm on the north. Here, wrote one Southerner, “within a few feet of each other these brave men, Confederates and Federals, maintained a desperate conflict.” A disbelieving Federal colonel attempted to describe the “the carnage inflicted on us boys in Blue [but it] would be impossible to detail.”284 Another Union officer could hardly believe how Barksdale’s rapidly-firing men, who seemingly never missed a shot, “liked to have killed them all before they could get away.”285

As on no previous battlefield, the hard-hit “Red Legs”of the 114th Pennsylvania, considered one of Pennsylvania’s “star regiments,” fell in ever-greater numbers, while hundreds of Union troops were hurled rearward by Barksdale’s onslaught. These finely-uniformed city Zouaves, with clerk the most common occupation but also including “rowdies of the city,” from Philadelphia’s close-knit, insular neighborhoods, found themselves in serious trouble. Quite simply, these city boys from the “City of Brotherly Love” were no match for the young country boys, backwoodsmen, small farmers, and hunters from across Mississippi.286

On the Mississippi Brigade’s left flank and duplicating Humphreys’ hard-hitting performance on the right, Colonel Griffin’s 18th Mississippi packed a hard-hitting punch that sent the Yankees reeling. He described how, “We steadily advanced, driving the enemy before us.”287 After unleashing their last devastating pointblank volley, Barksdale’s men closed in for the kill with bayonets. With slashing sabers and jabbing bayonets, the Mississippians literally tore apart the Pennsylvania formations.288 To the south of the Griffin’s 18th and Carter’s 13th Mississippi, respectively from left to right, the hard-charging 17th Mississippi likewise inflicted considerable damage, “leaving the ground nearly covered with their dead,” wrote Private Henley of the systematic devastation of the city boys.289 As emphasized by Private Thurman Early Hendricks, a member of the Minutemen of Attala, which attacked on the 18th Mississippi’s right flank, the 13th Mississippi once again reconfirmed its hard-won reputation as the “Bloody 13th” in the close combat, including hand-to-hand.290

From his perch atop Cemetery Ridge to the northeast, Captain Haskell described the dramatic sight of the devastation wrought by Barksdale’s knock-out blow, writing how the Third Corps troops now “fight well, but it soon becomes apparent that they must be swept from the field, or perish there. It is fearful to see…. To move down and support them with other troops is out of the question. There is no alternative—the Third Corps must fight itself out of its position of destruction!”291

As on so many past battlefields, the brigade’s crack regiment, the 21st Mississippi, achieved the most significant tactical gains of any of Barkdale’s regiments, delivering the blow that collapsed the salient angle and crushed its stunned defenders. With rounding yells, a close-range fire, and jabbing bayonets, Humphreys’ troops smashed through the apex of the Third Corps’ protruding salient angle, and then continued on without stopping to rest or reload. Charging astride the Wheatfield Road which led directly to the sector’s highest ground, the knoll of the Peach Orchard, Colonel Humphreys’ regiment struck a decisive blow that overpowered and crushed the salient angle, thus beginning the process of unhinging both arms, one extending northeast along the Emmitsburg Road and the other southeast down the Wheatfield Road.

The 21st Mississippi’s left ripped into the vulnerable and exposed left, or southern, flank of the 114th Pennsylvania—a flank that hung in mid-air—while its right struck the equally exposed right of the 68th Pennsylvania, situated just south of the intersection along the Emmitsburg Road. Because of the wide gap that extended between the left of Cavada’s regiment and the 68th Pennsylvania’s right, Colonel Humphrey’s troops penetrated sufficiently deep into the Peach Orchard on the left to outflank both regiments.

The right of the 21st Mississippi, yet astride the Wheatfield Road after crossing the Emmitsburg Road, continued to maul the 68th Pennsylvania, while the 114th Pennsylvania suffered severely from a flank fire unleashed by the 21st Mississippi’s left. In essence, the 21st Mississippi smashed simultaneously into the ends of two vulnerable flanks, and then penetrated the gap. A hard-fighting 114th Pennsylvania captain, Edward R. Bowen, was amazed by the lethal effectiveness of the Mississippians’ slashing attack. He wrote with surprise how “the enemy had already advanced so quickly and in such force as to gain the road” hardly before the Pennsylvanians knew what had hit them. Sensing a dramatic victory with the smashing of the Peach Orchard angle, Colonel Humphreys encouraged his 21st Mississippi soldiers onward to exploit their significant gains without pausing. With fixed bayonets and firing on the run, these hardened veterans continued to charge thorough the choking smoky haze that made them look like ghostly devils from hell suddenly emerging to the hard-pressed boys in blue.

Colonel Andrew H. Tippin’s 68th Pennsylvania had just attempted to advance in a belated attempt to close the dangerous gap and support the battered left of the 114th Pennsylvania. But by this time it was far too late for such an adroit maneuver. The 68th Pennsylvania was thoroughly punished under the sledgehammer-like blows of the 21st Mississippi’s right. Bolstered by the 2nd New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, Burling’s brigade, Humphreys’ Division, that had moved to its rear, after changing from front from facing south to west toward the 21st Mississippi, the 68th Pennsylvania attempted to confront the seemingly unstoppable momentum of Humphreys’ onslaught as best it could. A calm Colonel Tippin ordered his troops to hold their fire until the rampaging Mississippians were close. A concentrated volley from the 68th Pennsylvania momentarily staggered the 21st Mississippi, knocking down a good many attackers. Feeling a sense of admiration, Private McNeily described how the Yankees “fought back bravely,” standing firm for as long as they could.

Screaming orders above the guns’ deafening roar, Humphreys hurriedly formed his troops along a fence that ran along the Wheatfield Road to reorganize his ranks, allow his panting men a breather, time to reload, and provide some protection amid the open field swept with a torrent of bullets. Here, the soot-smeared veterans from companies like the Hurricane Rifles, Sunflower Guards, and Vicksburg Confederates busily reloaded and returned a devastating fire upon the New Hampshire and Pennsylvania troops from the north. One New Hampshire soldier described the vicious combat as “close, stubborn and deadly work,” which was the bloodiest in the regiment’s history.

Meanwhile, in a most timely arrival, Colonel Holder and the 17th Mississippi’s right added timely strength to the busily engaged 21st Mississippi along the fence-line now swept by 68th Pennsylvania bullets. With the 13th Mississippi and 18th Mississippi’s right and the 17th Mis-sissippi’s left driving Cavada’s Zouave regiment rearward, the 17th Mississippi’s right turned to help exploit the gap between the 114th Pennsylvania and the 68th Pennsylvania, assisting the 21st Mississippi in timely fashion. Then, the two Mississippi regiments delivered a concentrated volley on Colonel Tippin’s 68th Pennsylvania near the small log cabin, with a stone foundation (the John Wertz House) which stood on the east side of the Emmitsburg Road. This blistering fire cut down the color bearer, dropping the 68th Pennsylvania flag, the regiment’s lieutenant colonel and major, and a good many fine men.

This well coordinated, combined one-two punch and blistering flank fire delivered by the 21st Mississippi and the 17th Mississippi’s right mauled the obstinate 68th Pennsylvania, whose right flank had been turned. Under heavy pressure, Tippin had no alternative, and the 68th Pennsylvania was forced to retreat. However, this sudden withdrawal left the 350-man 2nd New Hampshire, the first unit facing south along the Wheatfield Road, under Colonel Edward L. Bailey, exposed on the right flank to the 21st Mississippi’s onslaught. After having been dispatched to support Graham, the youthful-looking Bailey said he suddenly found “myself unsupported, and the enemy steadily advancing” with piercing, high-pitched yells that echoed over the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. After capturing more prisoners, including wounded Federals who took refuge in the Wentz House cellar, Colonel Humphreys ordered his troops to charge onward through the Peach Orchard and down the slope.

Surging east and parallel to the Wheatfield Road, the 21st Mississippi’s attackers forced the outflanked 3rd Michigan Volunteer Infantry to retire and then next slammed into the 2nd New Hampshire’s exposed right flank, thanks to the retreat of the Maine and Michigan regiments. Therefore, the 2nd New Hampshire was likewise forced to withdraw. After losing nearly 200 men and faced with encirclement by Humphreys’ attackers, Bailey ordered his battered regiment rearward around 150 yards across the grassy, open ground of the eastern slope of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge to about the Peach Orchard’s center to escape the 21st Mississippi’s furious onslaught. After sending the Pennsylvanians under Colonel Tippin reeling along with Colonel Bailey’s hard-hit New Englanders, Humphreys’ 21st and the 17th Mississippi’s right then focused their full attention to their next unfortunate victim, the 114th Pennsylvania and its vulnerable left flank hanging in mid-air to the northeast.

As greater carnage swirled around him and his devastated Zouaves, Captain Bowen described how the attacking 21st Mississippi’s left and the now reunited 17th Mississippi turned to enfilade the 114th Pennsylvania from left to right, or south to north. All the while, the onrushing Mississippians busily loaded and fired with an amazing rapidity, “pouring a murderous fire on our flank, threw the left wing of the regiment on to the right in much confusion.” Keystone State soldiers like Sergeant John R. Waterhouse, a steady Company F veteran at nearly age forty with a large Philadelphia family—wife Sarah and five children—went down when two bullets smashed into his right thigh, tearing flesh and breaking bone.

The fatal combination of “the enemy advancing so rapidly and my men falling in such numbers,” wrote Captain Bowen, the regiment’s acting major, explained how the 114th Pennsylvania was all but vanquished by the hard-charging Mississippians hardly before the fight had begun. Indeed, both the 21st Mississippi and the 17th Mississippi attackers, working together effectively with business-like efficiency as on past battlefields, continued to wreck havoc on the 114th Pennsylvania’s vulnerable left flank that was even more exposed, after hurling back the 68th Pennsylvania and the 2nd New Hampshire. Throngs of defeated survivors of the two battered regiments now headed east down the slope for Cemetery Ridge to escape Barksdale’s onslaught.

Barksdale’s regiments had not achieved their gains without paying a heavy price, however. James B. Booth, Company F, 21st Mississippi, described the escalating losses that decimated Humphreys’ regiment, including President Davis’ beloved nephew. Leading the young men of the Hurricane Rifles (Company E), darkly handsome, dignified Captain Isaac D. “Stamps was killed [mortally wounded] in three feet of me [when] we were just entering the peach orchard when he was stricken down.” As a cruel fate would have it, Captain Stamps went down with a bullet through his bowels, while he was waving the ornate saber that Colonel Jefferson Davis had carried during the attack of the First Mississippi Rifles at Buena Vista. Stamps’ haunting prophecy about receiving a death stroke had been fulfilled in tragic fashion. Private Henley, 17th Mississippi described with a mixture of pride and sadness, “We went through the Peach Orchard [but] lost many” of the regiment’s best soldiers, both officers and enlisted men.

On the brigade’s right, Humphreys’ gains were growing. In the face of the 21st Mississippi’s onslaught, the two out-flanked regiments, the 68th Pennsylvania and the 2nd New Hampshire, were simply swept aside. Most important after having hurled back the two Federal regiments, Humphreys’ 21st Mississippi effectively flanked the Peach Or-chard salient and Union regiments, starting with the 114th Pennsylvania, on the left, and the 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry (the farthest south regiment), on the 68th Pennsylvania’s left.

This gaping hole was fully exploited when Humphreys’ men charged ahead to widen the fissure in the defensive line that grew with each passing minute, collapsing Sickles’ determined bid to hold the salient’s apex like a pierced hot air balloon. Thanks to the 21st Mississippi’s hard-hitting style, the smashing of the line’s apex was the beginning of the end for Sickles, his Third Corps, and the Peach Orchard salient, resulting in a classic case of falling dominoes. Private McNeily, 21st Mississippi, recorded how the steamrolling “21st struck and flanked the Peach Orchard angle,” delivering a powerful blow that collapsed the salient as Barksdale and Humphreys had originally envisioned.

But the most extensive damage was inflicted by Humphreys’ 21st Mississippi after it surged across the Emmitsburg Road and began charging southeast along the Wheatfield Road, which was lined with a lengthy row of Union artillery. To Humphreys’ delight and making his tactical dreams come true, the Wheatfield Road now became a golden avenue of opportunity for Barksdale’s most hard-hitting regiment. After overrunning the salient angle and continuing to advance southeast over open ground beyond the body-filled Peach Orchard, the 21st Mississippi’s devastating blows continued to wreck havoc at every point. In the words of Colonel William R. Livermore, once “the apex of Sickles’ line was broken, both wings collapsed.” But this sudden collapse had required much hard fighting by both Barksdale and Humphreys in order to push aside the stubbornly defending Yankees.

All the while, the number of victims of the 21st Mississippi’s assault soared. Continuing to wreck one Federal unit after another and despite the lack of contact with Kershaw’s brigade to the right, Humphreys’ regiment reaped more success by unhinging additional Federal regiments. It is also possible at this juncture that the Union troops could see Wofford’s Brigade coming up behind the 21st Mississippi, thus enhancing their fear of being overwhelmed. Afterward, however, Wofford would veer to the right, plunging into the hell of the Wheatfield.

The significant gains achieved by the 21st Mississippi presented a host of new tactical opportunities not only for the 21st but also for the 17th Mississippi, on Humphreys’ left. Working efficiently together as an experienced team, the 21st Mississippi and the 17th Mississippi sandwiched the 68th Pennsylvania, now in a new position near the Peach Orchard’s center after it retired east, between two irresistible forces, with Colonel Carter’s men turning the 68th Pennsylvania’s right and Humphreys’ troops turning its left. After the 68th Pennsylvania and the 2nd New Hampshire were driven back, departing in haste from the bullet-swept fenceline along the Wheatfield Road to escape the punishment, the 17th Mississippi, now slightly in the left-rear of the Union regiments along the Emmitsburg Road, had turned back to face northeastward to outflank the Pennsylvanians on their left.

After inflicting extensive damage on Cavada’s Pennsylvania Zouaves, Colonel Holder’s 17th Mississippi, now facing northeast and immediately to the right of the Emmitsburg Road, slammed into the left flank and rear of the 57th Pennsylvania around the two-story Sherfy house, and then headed toward the vulnerable left flank of the 105th Pennsylvania. Both Pennsylvania regiments took a severe beating under the close-range volleys unleashed by Barksdale’s men, who proved to be experts in delivering lethal fires and at cutting even fine Union regiments to pieces.