“The guiding spirit of the battle”

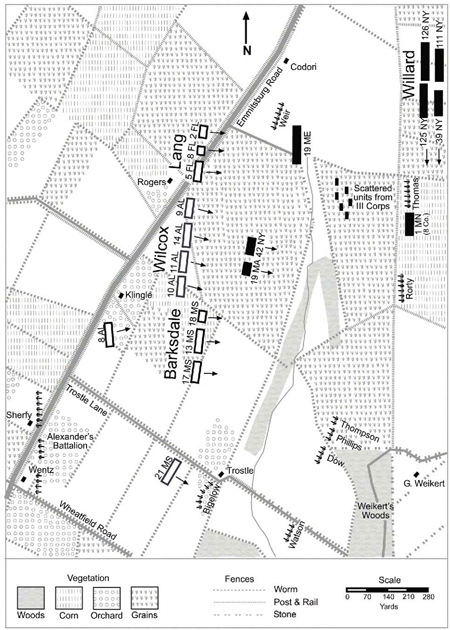

MEANWHILE, BARKSDALE CONTINUED to lead the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi northeast up the Emmitsburg Road, smashing resistance in the open fields to its east. After hurling aside the New Yorkers of the Second Brigade of Humphreys’ Division, Third Corps, the attacking soldiers surged onward to threaten additional units on the exposed left flank of General Joseph B. Carr’s First Brigade, Second Division. Union General Humphreys described Barksdale’s gains: “My infantry now engaged the enemy’s, but my left was in air … and being the only troops on the field, the enemy’s whole attention was directed to my division, which was forced back.” Humphreys realized that he had “never been under a hotter fire of musketry and artillery combined [and] for the moment I thought the day was lost.”

To the onrushing Mississippians, this fight was turning into a turkeyshoot, with the yelping Rebels loading and firing on the run as rapidly as possible. Crossing the east-west running Abraham Trostle Lane that led over the fields descending down to Trostle’s house and barn in Plum Run’s valley, they continued to charge onward with wild shouts. Despite the heavy losses and his men’s exertions, Barksdale still refused to halt the troops to either reload or rest with so many Federals on the run, and the left of Carr’s brigade giving way under the relentless pressure. No time, not a minute, could be wasted, if decisive victory was to be gained before the sun went down. During his sweeping attack along the Emmitsburg Road, Barksdale not only continued to inflict punishment on the vulnerable left flanks of additional Federal units aligned parallel to the road, but also on steadily retiring, but stubborn, Union regiments which had already been hurled out of the Peach Orchard.

With his regiment cut to pieces after losing nearly half of its numbers in tangling with the Mississippians today, Captain Edward R. Bowen, now commanding what little was left of the 114th Pennsylvania, continued to withdraw before Barksdale’s onslaught: “All this time we were being hotly followed by the enemy, and very close they were to us, our main endeavor being to get our colors safely off … what remained of the regiment, amounting altogether to not much more than a color guard, faced to the enemy and fired … the masses of the enemy were almost on them. We left the Emmitsburg road covered with our dead and wounded.” As the final insult, at least one Mississippi officer now led his elated troops northeast with a captured Zouave fez on his head: a trophy that inspired his jubilant troops in their steamrolling attack.371

With many Magnolia State officers already shot down, surviving leaders rose to the fore during the swirling combat. A 27-year-old farmer from Early Grove in north-central Mississippi was one such resilient leader. Lieutenant James, or “Jim,” Ramsuer was hit when a lead ball tore through the fleshy part of his cheek and mouth, barely missing bone and teeth. Nevertheless, he continued to lead his shouting Mississippi Rangers (Company B), 17th Mississippi, while splashed with red from the ghastly wound. The sight of a charging Confederate officer covered in blood no doubt unnerved some young men in blue. Rebel Private William Meshack Abernathy never forgot the inspiring sight of Ramsuer who, “with a shot square through his mouth, unable to speak, a sword in his right hand, his left hand shattered, holding the brim of his hat with his thumb and forefinger, was waving the boys forward.”372 Like so many other inspirational Mississippi officers, Ramsuer finally went down when hit by yet another bullet. But he was one of the lucky ones, surviving his wounds.373

Likewise many of the best fighting men from Barksdale’s enlisted ranks also had been cut down. One of the youngest Mississippi Brigade soldiers who fell to rise no more was teenage Private Ross Franklin, the fun-loving prankster of Company B, 17th Mississippi. Originally from the port of Mobile, Private Franklin had enlisted with high hopes of winning glory at only age fifteen.374

But such a high sacrifice in lives was necessary because of the tenacious fighting required for overcoming so many battle-hardened Federals, who had never battled so stubbornly because they were now defending home soil. However, the Mississippi Brigade’s attack had already achieved a measure of success beyond expectations. Indeed, Barksdale delivered a devastating knock-out blow to the formidable Third Corps, capturing not only the Peach Orchard salient angle but also the defensive line northeast of it along the Emmitsburg Road. Then, to the south, Humphreys rolled up Union infantry and artillery units like an old carpet along the Wheatfield Road. Graham’s brigade had been cut to pieces, losing 740 of 1,516 soldiers. Most important, the decimation and rout of Graham’s brigade exposed the right flank of the Union defenders along the Wheatfield Road, while assisting in Wofford’s and Kershaw’s success in sweeping across the Wheatfield. These hard-won Confederate gains in the bloody Wheatfield sector, however, ensured that the Mississippi Brigade continued to fight on its own hook. In the words of Private McNeily, “not from the time we charged until [nightfall] did our brigade get in touch with the other division brigades.”375

Serving on Sickles’ staff, Pennsylvanian Jesse Bowman Young described the collapse of the Third Corps: “Sickles was flanked and driven [and his units] without exception … were flanked, crowded back, and at last forced in more or less confusion toward the rear.”376 After smashing through Graham’s brigade, Barksdale then caught Carr’s and Brewster’s brigades on the left flank to inflict more damage. On this short afternoon, the Mississippi Rebels captured nearly 1,000 prisoners, which was more than two-thirds of Barksdale’s total strength. Barksdale’s onslaught was already one of the most devastating infantry assaults of the war.

One Union officer described the Mississippi Brigade’s attack, saying that neither musketry nor “cannon seemed to confuse or halt Barksdale’s veterans. We [had] five regiments fronting Barksdale’s small Brigade and these were supported by two additional Pennsylvania regiments stationed just behind the five … but nothing daunted Barksdale and his men and nothing seemed to be in their way [as they] came on, and on, and on, and when they came in gun shot of us, the carnage … inflicted on us boys in Blue would be impossible to detail. Before we could get to the rear, the ten guns were captured, the 80 horses killed and they drove the five regiments from the field, ran over the two lines of reserves as the five regiments in front and carried everything before them with cyclonic force.”377

The 21st Mississippi had already been severely punished for its success, however. Anchoring the regiment’s left, the 40-man Jeff Davis Guards, or Company D, 21st Mississippi, was especially decimated, losing 9 killed, and 18 wounded. Already the 21st Mississippi, wrote one soldier, had “lost many of her best & bravest sons.” Nevertheless and as if he commanded a full brigade instead of a single regiment fighting almost alone, Colonel Humphreys continued to lead his soldiers down and parallel to the Wheatfield Road.378

Meanwhile, with Barksdale’s left resting on the Emmitsburg Road, the 18th, 13th, and 17th Mississippi, from left to right, steadily surged northeastward. With flashing saber and still mounted, Barksdale led his soldiers deeper into General Humphreys’ Division. Continuing to drive Brewster’s remaining New Yorkers of the “Excelsior Brigade” up the Emmitsburg Road toward Gettysburg, the Mississippi Rebels pressured the withdrawing 71st and 72nd New York Volunteer Infantry troops, which had been the first to break.

The elated 18th Mississippi soldiers continued to unleash their pentup rage against the remaining “Excelsior Brigade” troops, seeking a full measure of revenge for the capture of the 18th’s banner by the 71st New York during the second battle of Fredericksburg. And the homespun Mississippians obtained their long-sought revenge with considerable relish. In the words of the Excelsior Brigade’s Colonel Brewster, “the troops on our left being obliged to fall back, the enemy advanced upon us in great force, pouring into us a most terrific fire of artillery and musketry, both upon our front and left flank … the troops on our left being, for want of support, forced still farther back, left us exposed to an enfilading fire, before which we were obliged to fall back … but with terrible loss of both officers and men.”

Describing the bitter contest in the Emmitsburg Road sector, Private Abernathy of the 17th Mississippi wrote how “we drove [Graham’s bri-gade] back and on to the New York Excelsior Brigade, and here another desperate struggle resulted. Here was a battery of artillery, and around this battery, a terrific struggle ensued. Twice we took it, and then on a final charge we ran up over it.” Attacking in the surging ranks of the Kemper Legion (Company C), 13th Mississippi, Private Joseph Charles Lloyd recalled how “after a divergence to the left we ran over and capture[d] a battery.” This was just south of the Daniel F. Klingel House, a log cabin situated atop a knoll, immediately on the east side of the Emmitsburg Road north of where the Abraham Trostle Lane met the Emmitsburg Road.

Twenty-five-year-old Private John Alemeth Byers, a Water Valley, Yalobusha County farm boy of Company H, 17th Mississippi, fell along with quite a few comrades. Private Byers, one of the Panola Vindicators, was eventually captured on the field. He was fated to be killed in battle in 1864.

With the capture of this battery, Company K, 4th United States Artillery, along the Emmitsburg Road, an excited Private Abernathy “sprang on one of the guns and was shot off of it, but we held the battery, and then came another effort to retake it, but without avail.” The lithe private jumped atop the captured gun despite having just seen the first Rebel to do so get promptly shot off the piece. At the point of the bayonet, Barksdale’s men captured three guns positioned along the Emmitsburg Road. Adjutant Harman, 13th Mississippi, was elated “after crossing the Emmitsburg road [when] the Brigade continued to advance and a short distance beyond were the captured canon [sic], but I cannot say to what battery or batteries they belonged.” Immediately, veteran Mississippians manned the captured Napoleon 12-pounders, turning them on the Federals, who now felt the sting of their own shot and shell.

Barksdale and his three regiments continued northeastward. With full force, they hit the southernmost Federal unit—the 11th New Jersey, on their right just south of the Klingel House—of Carr’s First Brigade, which was the second to last (after the 12th New Hampshire) of the regiments of Humphreys’ Division still positioned along the Emmitsburg Road. Barksdale’s men mauled the left flank of Carr’s brigade with a fire so deadly that one Yankee officer feared that “it seemed as if but a few minutes could elapse before the entire line would be shot down.” All the while, the Mississippians continued to deliver punishing blows at the “several new lines of battle which appeared to be reinforcements of fresh troops,” wrote Adjutant Harman, 13th Mississippi.

The 11th New Jersey, organized near Trenton, was hurled back. Veterans of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, the New Jersey boys were brushed aside like Graham’s Pennsylvanians and the New York regiments. Upon earlier having taken position on high ground along the Emmitsburg Road near the orchard of the Klingel farm, regimental commander Colonel Robert McAllister, 11th New Jersey, wisely positioned his troops to “fire by rank, rear rank first, so as to be enabled to hold in check the enemy after the first fire [but] our own men around the house and garden seemed to remain as though no enemy were near them … the rebels took possession of the house and garden and I ordered ‘Fire!’ at which time I fell, severely wounded by a Minie ball in my left leg and a piece of shell in my right foot, when I was carried to the rear.” Meanwhile, McAllister’s regiment was vanquished by the Mississippi Rebels, who continued attacking up the slope toward the top of the knoll, where the Klingel House stood. Not only was Colonel McAllister cut down but also the major who had just taken command of the heavily pressured regiment. Likewise, the regiment’s senior captain was hit by the scorching fire. Clearly, the Mississippi Rebels were especially efficient at targeting officers, especially when exposed on high ground. In total, Barksdale’s men shot down 153 of the 275 11th New Jersey men, who now lay sprawled across the open fields lining the Emmitsburg Road around the Klingel House.

In this emergency situation, Adjutant John Schoonover quickly took command of the 11th New Jersey, but he could only watch its further decimation in horror. Schoonover described how “the fire of the enemy was at this time perfectly terrific … men were falling on every side [and] more than half of our number had been killed and wounded.” Attempting to rally his reeling troops, Adjutant Schoonover himself shortly fell with two wounds.379

After the regiments of the Excelsior Brigade and the 11th New Jersey had been swept aside, Barksdale’s three regiments continued to charge across the open fields to the right of the Emmitsburg Road, keeping up the momentum. The exposed left flank of another regiment of Carr’s First Brigade was their next target. Just north of the Klingel House, immediately to the road’s east, stood the 12th New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. These 224 “granite-hard veterans” presented a formidable challenge to the Mississippians, who were by now winded and had already suffered heavy losses. Indeed, the New Englanders were reliable veterans of imposing size, both in height and muscular bulk. Most significant, these rawboned soldiers had already earned respect from their opponents. Consisting of American-born “mountaineers” of mainly Scots-Irish stock, this hardy New Hampshire regiment also included sturdy fighting men from Wales, Canada, Scotland, and Germany.380

At Chancellorsville, the 12th New Hampshire troops had demonstrated their stubbornness by holding Confederate attackers at bay with a determination to fight “until the last man falls.”381 Firing from behind the cover of trees and logs, they had nearly fulfilled their promise, losing more men (72 in fatalities alone) than any regiment on either side during the battle.382

With his lieutenant colonel cut down at Chancellorsville, Captain John F. Langley now commanded the 12th New Hampshire, just north of the modest, two-story Klingel House. In a spirited repeat performance of Chancellorsville, the regiment was standing firm before the belated advance of Cadmus Wilcox’s Alabama Brigade from the west, when all of a sudden they were hit on the left flank by Barksdale’s three regiments. Humphreys’ Division was now caught in an ever-tightening “Confederate vise,” between Barksdale from the left flank and Wilcox from the front. Therefore, immediate orders were issued for the New Hampshire boys to fall back to Cemetery Ridge before the regiment was crushed.383

Just northeast of the Klingel House the 16th Massachusetts, consisting of Middlesex County men under Colonel Waldo Merriam, who fell wounded, then Colonel Port D. Tripp’s 11th Massachusetts, farther up the road, were Barksdale’s next victims. As in earlier routing Graham’s brigade from Philadelphia, the mostly lower and middle-class farm lads from Mississippi now vanquished more city boys in the 11th Massachusetts, men from Boston, after pushing aside the mostly farmers of the 16th Massachusetts. One Union officer described how the onrushing Mississippians killed a good many Massachusetts men, including those of the “Boston Volunteers,” before “they could get away” from the onslaught on their flank while hit by the Alabamians in front.384 Indeed, the 11th Massachusetts, which had first fought in the Peninsula Campaign, lost 129 out of 286 men in the bloody Emmitsburg Road sector, including nearly 40 soldiers either killed or mortally wounded.385

After smashing the famed Excelsior Brigade and, with Wilcox’s assistance, rolling up the bulk of Carr’s First Brigade, including the 12th New Hampshire and the two Massachusetts regiments, Barksdale and his men, advancing immediately east of the Emmitsburg Road, still faced northeastward. After smashing through Carr’s brigade, Barksdale’s troops then struck the left flank of the 5th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry of Colonel George C. Burling’s Third Brigade. But Barksdale, after the last blue troops were swept away and having gained the top of the Klingel House knoll, now realized that he could not possibly achieve decisive victory by continuing to attack up, or parallel to, the Emmitsburg Road as originally envisioned. He had already gained the highest ground along the Emmitsburg Road Ridge at Klingel’s open knoll, and now the ground sloped down toward Gettysburg to the northeast. Barksdale realized that smashing one Union regiment after another was only bringing him closer to the Union center, with the Army of the Potomac’s primary concentration of forces, and not Meade’s left flank.386

Almost as if he had never been the cerebral, ever-opinionated editor of the leading newspaper in Columbus, a well-known attorney, and a respected politician in what now seemed like another lifetime, Barksdale’s natural leadership and tactical instincts rose to the fore. He fully realized that he was not moving toward Meade’s exposed left flank but only smashing through the Third Corps’ right, not yet gaining eliminating any possibility of inflicting a decisive blow. The Army of the Potomac’s real left flank, because of the Third Corps’ absence, was now located to the left of the Second Corps far to the east on Cemetery Ridge, where Sickles’ Corps should have been positioned had not the New Yorker advanced to the Peach Orchard.387

By this time after sweeping so many Yankee units off the Emmitsburg Road Ridge like a giant broom and overwhelming the highest point (the Klingel knoll) at its northern end, Barksdale realized that the Peach Orchard position had been only an advanced salient, or bulge, in Meade’s line, and that the main Federal position lay to the east on Cemetery Ridge. Demonstrating flexibility in this key situation, Barksdale thus made adroit tactical adjustments to adapt to the situation on the fly. With maneuvering his lengthy formation now relatively easy amid the wide, open fields that descended toward the low ground of Plum Run to the east, he quickly shifted his three regiments from a northeast direction to face straight east toward Cemetery Ridge.

After the Third Corps had been mauled and hurled rearward, Cemetery Ridge now lay undefended in a wide area south of the Second Corps’ left, behind the Trostle House and barn to the east. Indeed, the gap was even larger now than before, as the Second Corps’ leftmost division, Caldwell’s, had been dispatched into the inferno of the Wheatfield. The key strategic high ground, which was to have been the Third Corps’ wellsupported defensive position before Sickles advanced to the Peach Orchard, was now undefended as what little remained of Sickles’ Corps now streamed rearward.388 Therefore, Barksdale was determined to exploit the more than 500-yard gap between the Second Corps and the Fifth Corps on Little Round Top. The golden tactical opportunity that offered the most decisive results of the day lay directly before Barksdale, and he was determined to exploit this opportunity to the fullest.389

Here, on the high ground amid the little smoke-wreathed orchard just north of the log Klingel House, Barksdale sensed the chance to drive a wedge completely through the Army of the Potomac’s left-center. He therefore galloped before the lengthy butternut-hued formations of his three regiments, which were now facing toward his ultimate objective, which, if gained, would cut Meade’s Army in half. And now a colorful carpet of crop lands—entirely devoid of Union defensive lines—lay along the eastern slope of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge toward Cemetery Ridge, promising a relatively easy march to gain the high ground on Plum Run’s east side and win the war’s most decisive victory.390

Barksdale would now follow the shattered Third Corps units fleeing east—instead of northeast—toward Cemetery Ridge. Before moving onward with his 18th, 13th, and 17th Mississippi, Barksdale hurled a lengthy skirmish line down the sloping ground and through the open fields of the Trostle Farm, before launching his audacious bid to bring about the victory. Knowing that more hard fighting lay ahead in advancing farther east and hopefully all the way to Cemetery Ridge, wrote Adjutant Harman in a letter, “Gen’l Barksdale sent back twice for reinforcements,” but to no avail.

From this high point atop the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, which was now strewn with the bodies of blue and gray, just north of the Klingel House, Barksdale led his troops off the high ground and through the rows of fruit trees of the Klingel Orchard just north of the house. With confidence for success despite having suffered heavy losses, the Mississippi regiments advanced east with high hopes and red battle-flags flapping in the smoke-laden air. On the left flank, Major Gerald, 18th Mississippi, never forgot the dramatic moment when Barksdale’s attack continued down the eastern slope of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, when the three regiments “moved through the orchard and towards the heights” of Cemetery Ridge. Beyond the right of his three Mississippi regiments, Barksdale could see the large red Trostle barn to the southeast. Barksdale now surged east like his hard-charging top lieutenant, B.G. Humphreys, who continued to push onward astride the Wheatfield Road.

Once again, high-pierced “Rebel Yells” erupted from the throats of seasoned troops of Barksdale’s three regiments, resounding over a picturesque, open landscape—a farmer’s paradise but a soldier’s hell— turned red. Mounted out in front and leading the way, Barksdale pointed his sword toward his final ambition, Cemetery Ridge, which loomed on the eastern horizon about a half mile away. As in earlier targeting the Sherfy House as a focal point of the attack to gain the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, so Barksdale now utilized another prominent man-made feature upon which to guide his attack—the red Trostle barn, on his right-front. He now led his lengthy line of troops over the sloping ground northwest of the imposing red barn and the farmer’s white-painted house, located about 600 away. As repeatedly demonstrated on past battlefields, the Mississippi Rebels continued to prove to be as unstoppable as their white-haired commander. Miraculously, in leading the way, he had not yet been hit by a bullet or fragment of shell.

Throughout this sweltering afternoon and despite the swirling smoke of battle and rising dust that mixed together to obscure the field, Barksdale continued to demonstrate tactical flexibility, skill, and resourcefulness. He had adjusted repeatedly to meet a host of new challenges in an everchanging battlefield situation. Without specific orders or directions from Lee, Longstreet, or McLaws, and without immediate support to the rear or on his flanks, Barksdale continued to advance on his own in independent command of three regiments: a situation that allowed maximum tactical flexibility. Indeed, far from Barksdale, Longstreet and McLaws were yet focused on developments not north but south of the Wheatfield Road.

Across the colorful stretch of pastoral expanse, the Trostle House could not be clearly seen by Barksdale and his top lieutenants from the eastern slope of Emmitsburg Road Ridge, because the large red barn stood before the much smaller house, which was situated on slightly lower ground closer to Plum Run. However, like no other man-made feature in this sector, the Trostle barn, built of red brick and resting on a sturdy rock foundation, dominated the rolling landscape to Barksdale’s southeast. Nothing now lay before Barksdale but a wide stretch of open ground that dipped gradually down into the shallow valley of Plum Run, which flowed slowly just in the rear of the Trostle house.

With a sense of renewed confidence, the Mississippians headed steadily toward the lengthy, open stretch of Cemetery Ridge, where decisive victory now lay for the taking. Meade’s aide-de-camp, his son Colonel George Meade, Jr., recalled how during this crucial time, “affairs seem critical in the extreme [as] the Confederates appear determined to carry everything before them. Will nothing stop these people?” The hard-fighting Mississippians were indeed proving that they were, in the words of one Southerner, “irrepressible” on this bloody afternoon.391 Like Meade’s son, Captain Haskell asked after the Third Corps had been smashed and pushed aside, “What is there between” Cemetery Ridge “and these yell -ing masses of the enemy?”392

But despite vanquishing every Yankee regiment he had encountered along the Emmitsburg Road, there was still plenty of enemy fire to cope with. Although droves of Third Corps men were fleeing pell-mell from the field, others, singly or in groups, stopped at intervals to fire back at their pursuers. General Humphreys claimed to have personally halted his men 20 times to return volleys. Union regiments such as the spunky 12th New Hampshire continued to fight back with spirit, even as they withdrew, keeping up a harassing fire and dropping more Mississippi soldiers from the ranks.393

Tall in the saddle, General Barksdale continued to serve as an inspirational force to his troops. Private Abernathy of the 17th Mississippi recalled how the onrushing men were inspired by Barksdale’s exhilarating “order ‘Forward with Bayonets’ and over the wheat fields.” With reloaded muskets, the rejuvenated Mississippians continued to surge down the slope with high-pierced war cries that echoed over the broad expanse of Trostle’s fields. By this time the fighting that had swirled so savagely had “kindled in [Barksdale] an incandescence.” Indeed, the general’s fighting blood was up. He was invigorated by the sweet taste of victory in the sulfurous air. The series of dramatic successes reaped by Barksdale likewise inspired his troops with the unshakable conviction that they could continue to do the impossible this afternoon. Like a man possessed, Barksdale continued to serve as the primary driving force for his attackers. Clearly, and like his top lieutenant Humphreys to the south, Barksdale was having his finest day. But Barksdale was not basking in his success because he wanted to achieve much more; or as Longstreet put it, he “moved bravely on, the guiding spirit of the battle.”394

With discipline and in firm ranks that displayed years of training and discipline, the Mississippi Rebels moved relentlessly onward down the slope. Most important, “though in ‘rough uniform and with bright bayonets,’ these veterans, now covered with dust and blackened with the smoke of battle, with ranks depleted by shot and shell, and faint from exhaustion, responded with cheers to the clarion call of the intrepid Barksdale…. Mounted and with sword held aloft ’at an angle of fortyfive degrees,’ he exclaimed: ‘Brave Mississippians, one more charge and the day is ours’!”395

Exchanges of musketry continued to erupt across the open fields of farmer Trostle, but no fresh, organized formation of blue now stood east of the Emmitsburg Road before Barksdale’s fast-moving ranks. During their flight east toward Cemetery Ridge, however, the most resilient survivors of the broken Third Corps units still turned to offer resistance. These Federals blasted away from behind fences and few rocks too heavy to have been cleared even by the industrious German farmers. Here, stubborn pockets of defiant Yankees made brief defensive stands around their brightly colored flags, unleashing a continual harassing fire.

However, this persistent, pesky fire continued to drop Mississippi Rebels, increasing the butternut attackers’ ire and fueling their burning desire to reach Cemetery Ridge as soon as possible. Earlier, when Sergeant Joshua A. Bosworth, 141st Pennsylvania, fell wounded, he received initial compassion from onrushing Mississippians instead of a swift bayonet thrust. He asked a passing Mississippi Rebel for water. With compassion, the powder-stained Rebel handed his canteen to the injured Yankee. Meanwhile, the ragged Mississippian busily reloaded his rifled musket, but suddenly had second thoughts about assisting an enemy, who might mend and kill him or one of his comrades, perhaps even a relative, one day in the future. He consequently yelled to the injured Pennsylvanian that he “hated our men …” And as if to prove his point and to reveal how much the war had changed since its early days, this veteran, whose sense of Southern “patriotism” overcame his fast-fleeting compassion after having seen so many friends, or perhaps a relative, killed, had a change of heart. After rushing forward a short distance, the Rebel stopped, turned and then fired at the wounded Federal, who had just drank from the Mississippian’s canteen.396 For this Johnny Reb, it was too late for chivalry or other niceties of a brother’s war.

A lucky survivor of the Mississippians’ onslaught, one dazed Union prisoner offered a rare compliment to the Mississippi Brigade’s combat prowess. As Private Joseph Charles Lloyd, 13th Mississippi, described the encounter after “we ran over a battery of seven guns [and] the major commanding them [stated] ‘Why, you were the grandest men the world ever saw [and] you made the grandest charge of the war.’ ‘Your line was perfect and you held it, too, long [and] I was giving you all the canister my guns could carry but you never halted, but charged right on over us’.”397

With drums beating and red battle-flags waving in the late afternoon sunlight, a mounted Barksdale continued to lead his lines forward down the gently sloping ground toward Plum Run, situated about three-quarters of the way from the Emmitsburg Road Ridge to Cemetery Ridge. The three veteran regiments, including Barksdale’s old 13th Mississippi in the center, moved relentlessly onward, easing ever-closer to Cemetery Ridge and the fulfillment of Confederate ambitions.398

Barksdale believed that if any troops in Lee’s army could deliver the decisive stroke to win the war, it was his Mississippi troops. He had complete confidence in his own 13th Mississippi soldiers, who now advanced with disciplined step in companies like the Spartan’s Band, Alamucha Infantry, Winston Guards, Secessionists, Newton Legion, Minute Men of Attala, Lauderdale Zouaves, Pettus Guards, Kemper Legion, and Wayne Rifles. The McElroy boys were just the kind of tough Celtic soldiers who he needed to win it all this late afternoon. Barksdale knew the McElroy band, of Lauderdale County’s Company E, quite well. These men never forgot how Miss Sophronia McElroy presented the company’s battle-flag to Captain Peter Henry Bozeman, who led the Alamucha Infantry of Company E. Unlike the half dozen McElroy soldiers of the yeomen class, Captain Bozeman owned ten slaves. Included in the ranks of the McElroy clan were two father-son teams, John R. McElroy, Sr. and his son John R., and Isaac R. McElroy, Sr., and his son, Isaac R.

The highest-ranking McElroy was Kennon, now the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, who was second in command of the 13th Mississippi. He had organized the Lauderdale Zouaves as part of the Zouave craze at the war’s beginning. Because of demonstrated leadership ability in leading the attack at Malvern Hill, Kennon McElroy took command of the 13th Mississippi when Colonel James W. Carter was wounded in that attack. McElroy won Barksdale’s praise for gallantry at Antietam, where he was wounded but remained in command of the 13th Mississippi On this bloody afternoon at Gettysburg, four of the McElroy boys were destined to be either wounded or captured in the Mississippi Brigade’s bid to win it all.399

A natural fighter in the warrior tradition of his forefathers, Kennon McElroy was now enacting an impressive repeat performance. After Colonel Carter was killed in leading the 13th Mississippi’s onslaught in the struggle along the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, the capable Lt. Colonel McElroy, who had been promoted for gallantry to second in command, once again led the 13th Mississippi during its greatest challenge. McElroy survived the holocaust at Gettysburg, but not the war that destroyed so much of his clan of self-sacrificing Scots-Irish warriors.400

On this day General Barksdale now rode a magnificent horse, a highspirited bay, which had been secured by the cunning of a horse-savvy Mississippi picket. He had “whistled” the animal, while the horse drank from the Rappahannock’s waters, across the river at Fredericksburg.401 In his diary, Private William H. Hill, of the 13th Mississippi, recorded how a magnificent thoroughbred “horse, belonging to the Yankee army, swam the river this morning to our lines.”402 The pickets had then presented Barksdale with the splendid animal. Knowing exactly where concepts of chivalry needed to end, the pragmatic Barksdale refused to return this “very fine horse,” evidently a high-ranking Union’s officer’s mount, despite repeated requests sent across the lines for the animal’s return.403 Whatever Federal officer, especially if now poised in Meade’s defensive line along the Cemetery Ridge, had lost his most prized horse, he could not have possibly imagined that a Mississippi general was now riding it and leading Lee’s most successful attack on July 2.404

Meanwhile, back on Cemetery Ridge with the Second Corps, Captain Haskell described the golden opportunity presented to Barksdale’s onrushing brigade at this time: “The last of the Third Corps retired from the field, for the enemy is flushed with his success…. The Third Corps is out of the way. Now we are in for it…. To see the fight, while it went on in the valley below us, was terrible—what must it be now, when we are in it, and it is all around us, in all its fury?”405 All the while, due to the collapse of Sickles’ Corps, a wide gap now lay open between the Second Corps on Cemetery Ridge and the Fifth Corps on the army’s far flank.406 “The way was open for Barksdale’s Confederate Brigade,” in the words of Union artillery officer Bigelow, “to enter, unopposed, our lines between Little Round Top and the left of the Second Corps.”407

To exploit the gains won by the Mississippi Brigade in overrunning the Peach Orchard and clearing the Emmitsburg Road of defenders, Colonel Alexander, the tall, lanky, and capable acting commander of Longstreet’s artillery, flew into action. Like a well-trained West Pointer (Class of 1857) with keen tactical insights about the importance of providing both close and timely artillery support for the advancing Mississippi Brigade at the height of its success, he rushed his six batteries on the double to the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road Ridge. Believing the remarkable success had been bestowed by “Providence,” Colonel Alexander “rode along my guns, telling the men to limber to the front as rapidly as possible” to exploit Barksdale’s hard-won gains. Sweat-stained and covered with black powder, the experienced cannoneers in gray were eager for the opportunity to play their part in exploiting the gains reaped by the Mississippians.408

Consequently, these experienced gunners of Alexander’s reserve artillery battalion, of Longstreet’s Corps, were “in great spirits, cheering & straining every nerve to get forward in the least possible time [and the more than twenty guns of] all six batteries [the Ashland Virginia Artillery, the Bedford Virginia Artillery, the Brooks South Carolina Artillery, Madison Light Artillery, Captain Parker’s Virginia Battery and Captain Taylor’s Virginia Battery] were going for the Peach Orchard at the same time and all the batteries were soon in action again.”409

Indeed, now believing that not only the battle but also the war had been all but won by Barksdale’s dramatic breakthrough, Alexander’s “battalion of artillery followed fast on the heels of Barksdale’s charging Mississippians and seventeen Confederate guns were planted on the high ground abandoned by the Federal troops,” advancing some 600 yards east on the double. Wrote an impressed Colonel Alexander: “I can recall no more splendid sight, on a small scale—and certainly no more inspiriting moment during the war—than that of the charge of these six batteries. An artillerist’s heaven is to follow the routed enemy and throw shells and canister into his disorganized and fleeing masses…. there is no excitement on earth like it. It is far prettier than shooting at a compact, narrow line of battle, or at another battery. Now we saw our heaven just in front, and were already breathing the very air of victory.”410

Winning the Confederate guns “general race and scramble to get there first,” the Louisiana battery, under the command of Captain Moody, a hot-tempered duelist who was obsessive about matters of honor, was “the first battery that reached the high ground of the Peach Orchard,” wrote a thankful Colonel Humphreys.411 The first Louisiana guns quickly unlimbered across the commanding perch near the Wheatfield Road and among the rows of peach trees. Moody then began firing with rapidity from just east of the Emmitsburg Road north of farmer Sherfy’s orchard.

But it was not easy getting so much artillery into ideal firing positions on the high ground north of the Peach Orchard along the Emmitsburg Road. Dead horses and wounded soldiers, blue and gray, and sections of wooden fences obstructed the unlimbering and placement of Alexander’s artillery. A 114th Pennsylvania soldier was surprised by the gray cannoneers’ display of humanity amid a scene of slaughter, when a seasoned “battery of the enemy came thundering down, and when the officer commanding it saw our dead and wounded on the road, he halted his battery to avoid running over them and his men carefully lifted our men to one side, and carried the wounded into a cellar of the house, supplied them with water, and said they would return and take care of them when they had caught the rest of us.”412

Alexander, who stayed in the Peach Orchard through the night, never forgot the carnage of the area, writing, “What with deep dust & blood, & filth of all kinds, the trampled & wrecked Peach Orchard was a very unattractive place.”413

Once unlimbered, Alexander’s guns turned on the fleeing Yankees now spread out in the open fields to the east leading to Plum Run. Erupting from the high ground of the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road Ridge, these fiery blasts raked the retreating Federals from behind, adding insult to injury and adding to the shock value of Barksdale’s hardhitting assault. By this time, Mississippi spirits could not have been higher, because they had finally received tangible support to follow up their success, even as the once-stubborn bluecoat infantry fled before them. Or as artillery chief Alexander put it after seeing the Union line collapse, “Now we would have our revenge, and make them sorry they had staid so long.”

By not advancing farther east, however, the Rebel artillery actually provided relatively little close-range support for Barksdale’s attackers, who surged ahead on their own. Captain Haskell described the severe limitations of Lee’s “long arm” units, which many Federals held in dis-dain: “The Rebels had about as much artillery as we did; but we never have thought much of this arm in the hands of our adversaries … they have courage enough, but not the skill to handle it well. They generally fire far too high, and the ammunition is usually of a very inferior qual-ity.”414 These severe limitations of Confederate artillery also played a role in sabotaging the best efforts of Barksdale and his troops this afternoon.

Meanwhile, Alexander and his cannoneers were jubilant with the extent of Barksdale’s success in overrunning the Peach Orchard. Colonel Alexander explained the tactical situation and elation after most of Sickles’ Third Corps had been swept aside by the Mississippi Brigade’s “unsurpassed” offensive effort: “When I saw their line broken & in retreat, I thought the battle was ours…. All the rest would only be fun, pursuing the fugitives & making targets of them.”415

Excited about the seemingly endless possibilities of the Mississippi Brigade’s remarkable success, an elated Alexander shouted to his elated artillerymen, “We would ‘finish the whole war this afternoon’.”416 But first, this requirement called for the capture of the strategic crest of Cemetery Ridge. Alexander himself realized as much once he had advanced and unlimbered his six batteries: “And when I got to take in all the topography I was very much disappointed. It was not the enemy’s main line we had broken. That loomed up near 1,000 yards beyond us, a ridge giving good cover behind it and endless fine positions for batteries.” For a moment the Georgian had felt that the Mississippi Brigade’s success had already had been a decisive one, but now he realized that Barksdale still had one more major obstacle ahead.417

Map courtesy of Bradley M. Gottfried