I

THE ELEPHANT IN THE CASTLE

While Tony and Chiquita sweated out the decision of the courts and hid away from Bostock in Erie, one hundred miles to the west, in Cleveland, Ohio, the Animal King played another hand, in his other game.

After exhibiting Jumbo II to New England crowds through the winter of 1902, Bostock shipped the elephant off to Baltimore. There, Jumbo broke out of his pen and tried to find his way out of the grounds. He was recaptured. The showman then hauled him to Cleveland and tried to sell him. Having billed the pachyderm as the “most savage elephant in the world,” he couldn’t have been surprised when his offer to the Wade Park Zoo was turned down.

His sales efforts having failed, Bostock positioned his big elephant as a curiosity at his Cleveland show. Forty horses carried him in a wooden cage to Manhattan Beach, at the edge of Lake Erie, and there, throughout the summer of 1902, in the company of his usual mates and alongside Madame Morelli, Captain Bonavita, and the formerly mad Professor Weeden, he held court in a “castle.” His biography was modified to match his new quarters. Not only had Jumbo caused the death of “hundreds” during his life, but in India he had been “used as a public executioner and has crushed the lives out of hundreds of criminals beneath his massive feet.” Most recently, at the Pan-American Exposition, he had marked his arrival “by killing a man.” He was “the worst elephant in the world,” and all it cost to see him was twenty-five cents.

Through the summer on the waterfront, Jumbo stood in his castle, as Big Liz and Little Doc gave rides. It had rained heavily in June, and Ohioans, released from indoors, poured into the menagerie. Crowds particularly liked feeding time with the elephants. With the exception of one incident when Jumbo roughed up a new employee who had entered his stall and teased him, he was most “reasonable.”

In September, after the children went back to school and the crowds thinned, the show on the beach closed. Stage sets were struck, cages were dismantled, and Bostock’s animals were loaded onto trucks and wagons and taken to the train station to move to winter quarters. Big Liz, Little Doc, all the other trainers and animals—everybody left Manhattan Beach.

Everybody but Jumbo II.

A man in Baltimore, claiming Frank Bostock owed him a lot of money, launched a lawsuit. Jumbo was attached to the suit, and a helpful Cleveland sheriff ordered Jumbo held until Bostock paid up.

Bostock left town and disappeared and the sheriff rued his decision. The elephant, he discovered, cost money. His oatmeal, peanuts, and bales of hay were expensive. A hired elephant keeper cost more than thirty dollars a week.“Something must be done about this pretty soon,” said the sheriff in early October.

In the middle of the month, the sheriff again complained that Jumbo’s daily needs—two bales of hay, barrels of water—were too much for the county budget. Bostock had been tracked to New York City, but he had not replied to inquiries.

Finally, and probably under pressure, Bostock settled the suit. Jumbo II was his again. And within days, the showman made an announcement. A bullfight manager in Mexico City wanted to buy the elephant to fight a bull in his show ring. Even better, he would pay Bostock $5,000 for his big pachyderm. The Animal King, who had been plotting for months for ways to get rid of Jumbo, now made it clear that he had every reason in the world to keep him alive.

Which is why it was an unfortunate coincidence when suddenly, and for real this time, the big elephant died.

Some said that Jumbo II had been poisoned. Others said that the elephant, left by himself in the cold amusement park in Manhattan Beach, had died of loneliness. He had been sick for days, they claimed, and was “longing to join his companions of the show.” What is certain is that someone who knew exactly when and where the elephant would die, and who knew exactly what sort of equipment to bring, quickly sawed off the elephant’s tusks. The “thief” was never apprehended.1

Jumbo II never stood a chance against the Animal King. But at least his menagerie mate Big Liz carried with her some news that softened—if only slightly—the fact of his untimely end. After Cleveland, Liz was moved on to shows in New York City. And on June 24, 1903, between 4 and 4:30 p.m., at the Sea Beach Palace in Coney Island, she gave birth to twins, weighing approximately 150 pounds each. To those who did not know the recent history of the elephant mother, the New York Times offered some help. “The father of the babies is Jumbo II,” the paper explained, “whom Liz met at the Pan-American Exposition twenty-two months ago.”

Big Liz and a baby elephant take tea at Bostock’s, at the Buffalo fair.

Frank Bostock established Coney Island as his base for the next few years, opening a show in a brand new amphitheater and staging performances for fifteen thousand people daily. He continued to exhibit elephants, including one named Blondin, who in 1908 walked a tightrope and smoked a pipe. Many of his trainers, including Jack Bonavita, remained with him. Bonavita lost an arm to a lion in 1904, and then, following an attack by a polar bear in 1917, his life.

Bostock continued to tour the United States through the 1910s, and also took his acts overseas to Cuba, Europe, Australia, and South Africa. He expanded his business to theaters, ballrooms, and skating rinks. Then, suddenly, in London, in October 1912, Frank Bostock died.The cause of his death at forty-six, it seems, was influenza, and his funeral, by all accounts, was grand. Floral tributes arrived from business partners around the world—wreaths with a lion’s head, a floral kangaroo, a life-sized lion. Carriages to the Abney Park Cemetery north of London brought friends and admirers. Later, his family erected a tombstone with a big marble lion, recumbent and sleeping, for his resting place.

In memoriam, the press talked about the practices of the “Great U.S.A. Bostock,” as he was known. He was, the New York Times said, a man with a talent for staging remarkable publicity stunts. Others stated that his courage with wild animals was legendary. Still more talked about his theories on animal training. Addressing rising public concern over animal welfare, they said that Bostock delivered correction as a last resort. And parroting decades of press releases, they claimed that his creed was “kindness, kindness, kindness.”2

Bostock’s longtime lion trainer, Captain Jack Bonavita, ca. 1903.

Through the twentieth century, elephants like Jumbo II and Big Liz continued to serve as public sensations. And, just like Bostock’s elephants, they were viewed with mixed emotions. Shortly after Jumbo II was killed, a circus elephant named Topsy was electrocuted at Coney Island, in front of thousands of adults and children. (An Edison motion-picture company filmed the event.) The press, weighing in on the event with the same blend of prurience and remorse it had shown at Buffalo, described Topsy as both an incorrigible man-killer and a docile pet. She came to her killing site as “gently and obediently as a child.”

Theodore Roosevelt provided the American media with more elephant stories (and more ambivalence) when he publicized his East African safari in 1908. While collecting animal specimens for American museums, he disparaged Native African hunters for their lack of sophistication, boasted about Western guns, and marveled at elephants. They were terrifying beasts, he claimed, and he filled his account with stories of maulings, gorings, and tramplings. When he killed one, he stood on top of the world. “I felt proud indeed as I stood by the immense bulk of the slain monster,” he wrote after a shoot, “and put my hand on the ivory.” After killing one pachyderm, he roasted pieces of its heart and “found it delicious.”

Roosevelt saw in the elephant something more than terrifying majesty, though. The elephant was intelligent, savvy to the ways of the hunter, and skilled at avoiding them—it was what made the animal such attractive prey. They were not only wise; they were sociable. It was fortunate that there were so many of them, said Roosevelt, and that there was no danger of extinction.

In the United States throughout the twentieth century, the reputation of elephants continued to soften. In parade after parade, circus after circus, they plodded their way into the public’s affection. They sat on balls, balanced on tubs, were laughed at and admired. Then in 2015, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus announced that it would retire its herd. The decline of elephant populations worldwide and the recognition that these giant animals might be gone forever played a part in the decision. But more effective than that were the protests of animal advocates, who publicized the way they were imprisoned, disciplined, poked, and pricked. They also emphasized that these mammals had a humanlike way of solving problems and expressed fondness, grief, and empathy.3

What took place in 1901 in Buffalo—where Jumbo II pushed against his confinement and suffered the consequences, and where the brand new SPCA fought to prevent a spectacle of animal killing—pointed toward this shift in thinking. Jumbo’s “moment” did not mark any watershed in public opinion, but it did reveal a dent in the belief that civilization meant the subjugation of wild animals, and it served as a sign of changes to come.

II

EVER AFTER

Released from Frank Bostock’s dominion, Tony and Alice Woeckener spent the winter of 1903 dreaming up new shows. Tony corresponded with “several little people” and considered putting together a traveling troupe, accompanied by the Woeckener family musicians. Best of all, a writer was working on a pantomime that would feature special scenery and star Chiquita. For once, the performer would headline a show that was not her personal drama.

Chiquita stayed in the Woeckener home for much of that winter, resting and eating. She gained weight. And she became pregnant. The event, not surprisingly, made national news. Nine months later, however, in mid-October 1903, Chiquita signed her last will and testament and was prepared for a caesarean section at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Erie. The surgery was described as “a last resort to save her life.” The operation did end up saving her life, but her son was stillborn.

Over the next decade, Chiquita, with Tony as her manager, continued to tour. She performed in the West, in Mexico, and throughout Europe. One visitor who saw her show in New York City in 1909 said that just as endearing as Chiquita was her proud and attentive husband. He carried her to the platform, and then watched her act. “His devotion to his, the smallest wife in the world, is seemingly unending.”

It was in the spring of 1928 that a Buffalo newspaper announced that Chiquita, who had returned to Mexico with Tony sometime earlier, had died in Guadalajara. She would have been around fifty years old. The paper knew that many of its readers would have no idea who Chiquita was, so it reminded them. She was the young woman, the paper explained, “whom gaping hordes milled and jostled to see when she appeared at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901.” The announcement said that Chiquita’s end “brought her merciful relief.” The choice of words suggests that she might have had a hard time toward the end of her life, but it is comforting to imagine it was just a turn of phrase. What is evident is that her last decades with Tony were good. The newspaper recounted the story of their romance in Buffalo and claimed that they lived happily ever after.4

Tony Woeckener and Alice Woeckener (Chiquita), ca. 1904.

World’s fair midways continued to be popular venues for displaying short-statured people like Chiquita. In the 1930s, it wasn’t just one Little Person who was featured; expositions hosted “midget villages” and “midget circuses.” By the late 1900s, though, individuals with extraordinary bodies were increasingly viewed as medical anomalies that needed to be fixed. The hospital room, in other words, picked up where the circus tent left off. At the same time, and partly as a result of being set apart for so long, Little People joined together to demand rights, respect, and, above all, a reconsideration of what a normal body really meant. Alice Woeckener, with Tony’s help, had staked a claim to freedom on her own. A century later, she would have had the support of a wide and loyal community.5

III

THE OLD ADVENTURER

When Rainbow City locked its gates for good on November 2, 1901, the head counters went to work and calculated that the Buffalo Exposition had seen more than eight million visitors. It wasn’t the twenty million the big talkers had predicted, or the ten million that would have set the accounts straight. It was, all things considered, a respectable number.

Almost immediately, frets about attendance were repeated farther south, when another show opened. On December 1, 1901, Charleston, South Carolina, welcomed visitors to the Interstate and West Indian Exposition for a six-month run. The fair’s designers eschewed color this time and went back to tried-and-true white. The fair, located on the grounds of an old Ashley River plantation, became known as the “Ivory City.” It recorded 675,000 guests.

Charleston fair directors brought in some Buffalo shows. The Cuba exhibit was reassembled, as were The Streets of Cairo, Darkness and Dawn, and the Esquimaux Village. And, in the opening-day parade, who should bring up the rear but elephants, lions, and zebras from one of Frank Bostock’s menageries.6

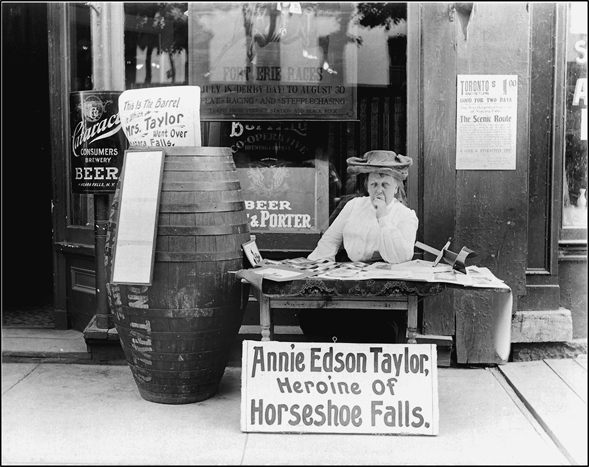

Another familiar face appeared, too: the barrel-riding star of Niagara Falls. The days since her bandstand appearance at the Pan-American Exposition had not been easy for Annie Taylor. While Tussie Russell booked engagements for her in early November, she had fought exhaustion. She persuaded Russell to take her back to Bay City, but even there, Annie said, Russell rented a storefront and “dragged me there more dead than alive.” She also complained that he didn’t give her all the money she made.

There had been other problems, too. Her story had made its way around the country, and, in Michigan, a blacksmith named Montgomery Edson had scanned the news about her exploit with more than usual interest—and perplexity. He became so deeply curious about the matter, in fact, that he decided to make himself known to the press.

He was, he said, Annie’s brother. There was only one set of Edsons who lived near Auburn, New York, and the details of her life fit with what he knew of his long-lost sister.

There was only one thing that didn’t match up. If Annie Edson Taylor was his sister, then she wasn’t forty-three years old. In fact, the person who had just dazzled the world with her nerve and daring was almost an old lady. And all those witnesses who said that she looked her age, and wondered whether she were past her dancing prime? They were right.

While papers in Michigan buzzed about Taylor’s age, Tussie Russell, who was taking offers for shows, kept silent on the subject. Annie, too, fired back. When a Bay City reporter asked her whether she was Montgomery Edson’s long-lost sister, she had a sharp answer. “He’s a fool,” she said. “I’m nobody’s lost sister and I never was lost.” But she did not deny the relationship.7

In mid-November, when Taylor began snapping at reporters and shooing away spectators, Russell drove her to a sanatorium for a rest. Several days later, the two were back on the road, holding court in Flint, Saginaw, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus. In most of these cities, Taylor sat in a department-store window, her cat (or, more likely, a cat) and her barrel by her side. Occasionally she gave a short talk.

They made almost no money. In Cincinnati, Annie explained, one of her fellow Niagara Falls stunters, Martha Wagenfuhrer, had arrived first, captured Annie’s audience, and “imposed on the public.” Annie tapped into an old Texas bank account in order to get to Charleston, and, after appearing at the fair for two weeks, she and Russell couldn’t even buy train tickets out of town. They turned to public-assistance offices for help.

Russell blamed their failures on Annie’s “peculiarities” and on her looks. “I’ve trottered [sic] her around the country,” the manager said, “but she got to be a frost. . . . People took more interest in the barrel and the cat than they did in the woman . . . they didn’t believe she was the woman.” He explained that audiences had imagined her as a youthful “damsel,” and that when they came face-to-face with the adventurer and found a woman “somewhat down toward the sunset side of life,” they took no further notice of her. They could have profited, he said, if she had been “a beautiful girl.”

With these ideas in mind, Russell made a break for it. Commandeering the barrel, he sold it to a Chicago theater company that wanted to produce a play based on Taylor’s ride. The manager of Over the Falls, as the show would be titled, suggested he might even have a part for Russell, either as hero or villain. He would not only feature the original barrel but also reimagine the heroine as lovely and young.

While Over the Falls went into rehearsal—according to theater circles, it seemed destined to be a hit—the barrel’s original rider struggled on. An appeal to the Ohio Relief Department in Cleveland gave Annie funds to go east and, in the winter of 1902, she returned to Niagara Falls. Desperate for money, she marketed postcards and produced a hastily written memoir. In late March, she wrote to a Niagara Falls theater manager for help. Tussie Russell, she said, had a “villinous [sic] temper,” and had proven himself rotten. He had taken her livelihood and made it his own. “Despair as bitter as death,” she said, “has settled down on me.”8

As money from souvenir sales accumulated, Taylor’s attitude shifted to determination. She hired a Chicago lawyer named Moody to find her barrel, and Moody, in turn, hired a detective. On August 14, he found it. The cask was brazenly being shown in a Chicago department-store window advertising Over the Falls.

Taylor made plans to go to Chicago immediately. Worried that the theater managers would do everything possible to thwart her, though, she decided to travel under an alias. Mrs. Isaac Davy, the name she chose, belonged to an acquaintance. She took with her a decorated alligator bag, so Moody would know her right away.

In Chicago, she and the lawyer, with the help of city police, moved fast. As a driver backed a truck up to the department store, an officer served papers on the manager. Moody’s assistants maneuvered the barrel into the truck and drove away. Twice that night, they switched the barrel’s location, and, by morning, they had the cask on an eastbound train, in the company of Annie Taylor. She was delighted.

Through early fall, Taylor toured northeastern state fairs with her prized possession. With her new manager, William Banks, she sold her memoir and photographs and spoke to audiences about her ride. At the end of September, she left for a new engagement in Trenton, New Jersey. As usual, her barrel traveled separately.

There was something about Annie Taylor that tempted men into usurping her story. Instead of reconnecting with Taylor, Banks took the barrel, dressed up a woman named Maggie Kaplin in clothes like Taylor’s, gave her Taylor’s books to sell, and launched a tour. Annie went to the Trenton justice of the peace to report her stolen barrel and met with other lawyers. Then, depleted of money and strength, she gave up. She could read about her barrel making the rounds of theaters in “startling,” “marvelous,” and “dramatic” renditions of her descent, but she never saw the real thing again.

The remaining years of her life saw the aging adventurer trying to market her feat with a replica barrel, and hawking souvenirs on the streets of Niagara Falls. She watched more theaters and filmmakers tell her tale and even toyed—briefly—with the idea of going over the falls again in 1906. Five years later, a forty-seven-year-old Englishman named Bobby Leach stole some of her thunder when he tumbled over Niagara Falls in a steel barrel. He was badly injured but survived. Taylor said she did not want to discuss the matter.

Annie Taylor sells souvenirs at a stand in Niagara Falls.

At the age of seventy-six, Taylor offered to portray herself in a movie about her pioneering plunge. She got into a barrel upstream of the falls and reentered it downstream. The production was never released. She dreamed up other schemes to make money, too, but now, nearly blind, she could not make them work. In the winter of 1921, she was admitted to an almshouse north of Buffalo. The registrar noted her “cause of dependence . . . sore eyes, no home, no money.” Other officials also noted her age. Ever the optimist, she had told them she was fifty-seven.

The poorhouse did not diminish Taylor’s willingness to give interviews about her adventures. Four trips across the Atlantic, she said, fourteen times across the Florida Straits, “several” times across the continent, and once deep into Mexico. And one other, of course. She also continued to reimagine her station in life. She told a newsman soon after she had been admitted that she was writing a historical novel she thought would be just right for Harper’s. Then she could leave the almshouse. “It is quite a change for me to come here when I have been used to being entertained in senators’ homes in Washington and travelling extensively,” she said.

She died there that spring, on April 29. She was eighty-three years old.9

Annie Taylor never succeeded in entering the high society she admired, either in 1901 or beyond. She was too poor, too restless. She also failed to secure a livelihood from her descent of Niagara Falls. She was, everyone said, too old. There were other problems. When men “conquered” Niagara by barrel, they were regarded as brave, if somewhat foolhardy. When they harnessed the cataract through engineering, they were seen as performing a brilliant, powerful, and profitable accomplishment. Taylor’s feat seemed to provoke as much irritation as wonder. Not only had she used an old-fashioned barrel to achieve her goal, but her act seemed to make the falls mundane. The “grandeur of the cataract,” explained a Niagara Falls park superintendent in 1902, “has been largely augmented by the fact that its dangers have been forever invincible by human beings.” When Taylor came along, he said, people “were resentful that anyone has triumphed over the mighty Niagara. They do not care to hear the story of a matronly appearing woman who has tripped up Hercules.”10

The grand escapade that culminated in Annie Taylor’s appearance at the Pan-American signaled change ahead for women, however. Women could vote by the time Taylor died, and women could travel alone with less suspicion. Eventually, women could enter the public sphere as politicians, professionals, and, thanks to the likes of Amelia Earhart, as adventurers. But, particularly if they were women of color, they would still contend disproportionately with poverty. And, for generations to come, older women would still be relegated to society’s backseat. Like Annie Taylor, many would try to defy their age, or lie about it, in order to capture the value accorded to youth.

IV

NIAGARA

Like every exposition, the Charleston fair that proved so disappointing for Annie Taylor was a magnet for controversy. Women in Buffalo had thought that a separate pavilion filled with women’s work was a backward step. Charleston women disagreed, and they proudly erected a building to show off women’s handicrafts and literature, and offered a place where mothers could deposit their babies. The Charleston exposition also featured a Negro Department headed by Booker T. Washington and a Negro Building with displays, including the Du Bois exhibit, which demonstrated African American progress since Emancipation. The building was set off in the “Natural” section of the fair, as opposed to the Art section with most of the other main buildings. A number of black Charlestonians objected to the segregation of both the Negro Department and the building, and also took issue with the art. A group statue in front of the building featured a “Negress” balancing a basket of cotton on her head, a man using an anvil, and another holding a banjo. Its designer claimed it celebrated African Americans for their “great ability as tillers of the soil and mechanics.” People of color in Charleston protested. They found the figures degrading and forced the statuary to another site on the grounds.

The Old Plantation concession from Buffalo’s Midway did not go to Charleston. What played well among white fairgoers in New York State would likely have fired a storm of anger in a city that was fifty percent African American and who knew, all too well, the truths of plantation life. Instead, the show moved on to Coney Island.

His stint as Laughing Ben thus over for the time being, Ben Ellington went back to Dublin, Georgia, and made a triumphant return. Having earned three dollars every week in salary, and as much as five dollars a day in tips, he brought back four hundred dollars. He hoped to buy a small house.

Ben became a town treasure. He was called on to greet distinguished visitors to Dublin and continued to use his talents to make money and to navigate his way through hard times. He avoided prosecution for occasional theft and laughed himself out of court fines. When he couldn’t produce identification, his laugh became his signature.

Ellington adopted a persona that worked for him. In a world of segregation and lynching, where black men met oppression at every turn, his performance as an inoffensive, happy man must have seemed a strategy for survival. As one newsman who met him commented, the old performer, despite his belly laughing, was “nobody’s fool.”

After completing several more national tours, Ben Ellington performed for the last time during the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904. He died back home in Laurens County, amid the red dirt hills he loved, in 1905.11

While Ben survived the Jim Crow era using his laugh, Jim Parker, who had tackled Leon Czolgosz in the Temple of Music, took his Pan-American fame on a different route. After hearing so often that he had been a “credit to his race” by aiding the stricken president, and after rejecting offers to go on stage in shows, he took to the lecture circuit.

In late December 1902, he reported receiving a new tribute. McKinley’s friend, Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio, wanted to do something to make up for the way that Secret Service men and others at Czolgosz’s trial had dismissed Parker’s brave act. Hanna offered him a position as messenger in the United States Senate.

If Parker took the position, or held it long, we do not know, but for the next three or four years he continued to speak, often under the auspices of the AME Church. A handbill printed in Worcester, Massachusetts, spoke of him as “The Greatest Negro of the 20th Century.” Despite such labels, or perhaps because of them, Parker struggled for credibility. His efforts to be believed for what he did in Buffalo became a mission, and the mission was clouded by illness. In Atlantic City, in the spring of 1907, he was “arrested in a demented condition” and charged with vagrancy. The press maintained that he had gone from street to street, telling his story to passersby and crowds that gathered. White commentators suggested he had been unable to handle the accolades that had been bestowed on him and had succumbed to “fast living.”

Hospitalized, Parker persisted in appealing for help from the people who knew him from Buffalo. Sometime in 1907, he penned a letter to Ida McKinley:

Kind Madam. I write you to ask a favor of you. I have been sick in the hospital for some time and am sick yet. I want you to help me. I done all I could for your husband in trying to save his life and if I had of been successful I know he would of [found a place for] me for my efforts a word from you to Mr. Cortelyou is all I need.

Parker said he would be happy for anything, from a place to live to a job driving a wagon. Please, he asked, “do this for me in remembrance of your dear husband.”

Ida McKinley asked George Cortelyou—who by then was serving in the cabinet under Roosevelt—to help Parker out with a job in Washington and a home in the district. Whether or not Cortelyou did something for Parker is unclear. What is certain is that Parker’s life did not turn around. In the winter of 1908, the police again picked him up, this time on the streets of West Philadelphia. He was admitted to the “insane” department at the Philadelphia Hospital, and in late March, at age fifty-one, he died. Having no connections in the city, his body was given to Jefferson Medical College, and, two weeks later, was set out on a dissecting table for the benefit of medical students.12

While James Parker died institutionalized and alone, other people of color who had been active at the Buffalo Exposition saw more enduring success. The local community that had brought the Du Bois Negro Exhibit to the fair did not let up. Mary Talbert, in fact, figured in another important story. In 1905, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote to Mary’s husband, William Talbert, about finding a “quiet place” for a top-secret meeting near Buffalo. The meeting would discuss strategies to counter the accommodationist policies of Booker T. Washington and to demand equal rights for African Americans. In early July, a group of men, including Du Bois, met first at the Talbert home and then at a hotel in nearby Fort Erie, Canada.

Barred from the meeting, Booker T. Washington asked his wife to write to Mary Talbert in Buffalo, to keep him “closely informed.” He also hired local men to spy on the gathering, and he tried to block newspaper coverage of the event.

He was right to be concerned about the clout of the men getting together. Du Bois and the others, who spent two days in discussion, were launching what they called the Niagara Movement. At some point in their deliberations, in fact, they made a short excursion to Niagara Falls. What Du Bois made of the falls at the time, he didn’t say, but later he described the cataract as one of the “wonderfulest” things he had ever seen, and he attached its name to his new organization. Four years later, the alliance broadened, its leaders joined with other activists, and it became better known as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The twentieth-century fight for civil rights was up and running.13

V

THE CENTER OF THE UNIVERSE

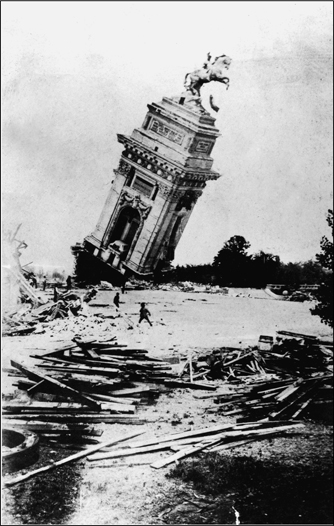

On July 1, 1902, after a week of gloomy weather, the sun emerged and, for the final time, struck the gilded iron statue on top of the Electric Tower with a bouncing light. A workman from the Chicago House Wrecking Company climbed the tower, fastened a rope around the neck of the Goddess of Light, and ordered men to pull. The statue somersaulted twice, plummeted into two feet of mud at the Court of Fountains, and broke into pieces. Witnesses at the scene were dismayed but not entirely disappointed. The statue had been sold to the owner of a popcorn pavilion in Cleveland, and, had the buyer appeared in time, would have had an ignominious end. “Cleveland, of all places—a popcorn joint, of all thrones,” lamented one journalist. Better, he suggested, to have her deep in the Buffalo dirt.

Rainbow City shut down in the first week of November, 1901, but it disappeared slowly. Unlike Chicago, which saw much of the White City go up in a conflagration four months after its gates closed, Buffalo lost its fair in increments. For almost eighteen months, residents watched buildings lose their plaster façades or go down with the wrecker’s ball.

The Midway was the first big section to go. By the spring of 1902, it was little more than a wasteland. Where once spielers, brass bands, and Bostock’s animals had filled the air with noise, now only sparrows cheeped, pecking away at grit and dust.

The buildings on the formal courts were brought down more gradually and stood as skeletons for months. Next to them, and in nearby Delaware Park, the ground was piled high with twisted metal and wasted wood. Those who visited the site said it looked like a hurricane had hit the area, while others wouldn’t visit the grounds at all, saying it was just too sad.

By the summer of 1902, the grounds were empty. A reporter, now relegated to covering humdrum life, looked back at the previous year. “You miss the Exposition if you’re a Buffalonian,” he wrote. Some parts of the fair seemed so completely erased, he added, “it is mostly a dream.”

Buffalo residents had tried to save some of the dream. Even before the Exposition’s end, city dwellers had plaintively wondered how they might hold on to it. “Must all the beauty and magnificence of the exposition be thrown away?” asked the Express. “Ten thousand times has the question been repeated in this city.” The loss of the beautiful buildings had weighed on visitors during the fair’s last days, the paper said, and robbed them of pleasure. The Exposition seemed like a fairy-tale beauty, “condemned to a horrible death by the giant ogre.”

The Triumphal Bridge in ruins, June 1903.

Ideas for saving some of the site poured forth. A local man suggested the grounds become a national park, because the president had been shot at the location. New Yorker John Carrère, the fair’s architect, threw out a different plan. The beautiful Pan-American fair had cost a lot of money. Why not keep the canals, the fountains, and even the Triumphal Bridge and the Electric Tower? Why not plant new trees and make use of the vistas? Think, he said, of “Versailles and Fontainebleau.” It would be an investment such as they make in Europe. If Buffalonians would only show the same “public spirit” they had earlier.

Carrère wanted Versailles. Others said they would be happy with a toboggan run. They pictured a mammoth slide running from the Electric Tower to the Triumphal Bridge, and then down the incline of Park Lake. The canals and fountain basins would become skating ponds, lighted at night. A concessionaire had an even more extravagant thought: Why not spray water onto the Exposition buildings and turn them into fanciful ice palaces? A local businessman thought the “scheme would, I venture to say, draw people from nearby cities.”14

But officials had had enough of such schemes. Who could dream of a new spectacle when they had not yet paid for this one—when, as one commentator put it, “the surplus was on the wrong side of the balance sheet?” The fair had cost close to $7 million and had brought in $6 million. Many contractors and laborers who had built the Exposition buildings had not been paid at all. Mortgage holders had been reimbursed, but not completely. Stockholders would see nothing.

The Exposition Company and all the people who had poured hearts, souls, and money into the fair hoped that Washington would help out with a million dollars. The federal government had not helped fund the fair, after all, as it had done for other big expositions; it had simply paid for its own exhibit buildings. And hadn’t the fair failed because it had hosted the president, with disastrous results? One newsman summed up the case: “The fact that the President’s death occurred in Buffalo at the time when the full tide was welling and that it stopped the growing throng and broke the thread of enthusiasm, gives the Exposition Company a certain amount of claim on the country at large.” Exposition directors brought out attendance numbers and projections that backed their claims—McKinley’s death, they said, had cost the corporation $1.5 million.

The fair’s movers and shakers knew, of course, that the Exposition’s losses were grounded in more than the death of an American president. They had had worries about low attendance back in the early summer, when immense crowds weren’t materializing. They had blamed the numbers on the weather: Spring snows and summer chills had delayed construction and dampened the enthusiasm of early visitors. They also thought that railroads hadn’t lowered rates soon enough. Concessionaires had other opinions. Closing the Midway on Sundays—turning the Exposition into “a funeral,” as some of them put it—turned off patrons. Others thought the advertising was off. Pan American promoters, they complained, did silly things like print ads “on miniature frying pans and beer mugs or in pretty booklets and folders.” If they had put an ad in a thousand daily papers, and run it for three months, it would have been far more effective.

Maybe, though, it boiled down to expectations that were too high. Looking back, William Buchanan described the attempt of a city of 350,000 to hold an international exposition without the financial backing of the nation or the state as a “hazardous undertaking.” And Marian De Forest, secretary of the Board of Women Managers, said that the city had held out too much hope for patrons across the Americas. “Those most familiar with exposition history,” she wrote, “have no hesitation in saying that it was too large for a city like Buffalo.”15

John Milburn, who would travel to Washington and ask for help, would never say such things. He reminded people that the fair’s officials—unlike the press—had really only hoped for ten million visitors, and the assassination had unraveled the rate of attendance. He also couldn’t let pity ruin the pride the city felt in hosting the Pan-American Exposition. He walked a fine line—he had to let the country know the Exposition Company needed help, but he needed to remind Buffalonians that they had done a magnificent thing. To local residents who had lost money, Milburn pointed out that Buffalo had just attracted a slew of new investors and that millions of people had emptied their pockets in the city. If anyone dared complain that the fair had not matched the success of Chicago, he asked them—how convincingly is unknown—to think again. “The pro rata expenditure at the Chicago World’s Fair was something like $14 for each visitor and as we have had a considerably better class of people . . . it is reasonable to suppose that the amount each visitor left here was at least $20.”

Buffalonians of less wealth had invested in the fair, too, and to them Milburn offered comforting—if financially unhelpful—words. They had had “their ideas broadened.” Furthermore, their hometown was now known. The Exposition, said its president, “has put Buffalo on the map of the great cities. It is no longer thought of as the town of which Grover Cleveland was once Mayor, but as the beautiful city on the lake where the Pan-American Exposition was held.” Throughout the previous six months, important visitors had admired the city’s fine homes and office buildings, its well-designed parks, and its asphalted avenues.

John Milburn also reminded people that the fair’s theme had been successfully executed. “We have not lost sight of the fact,” he said, “that the Exposition was held primarily to stimulate commercial relations between countries of North and South America. . . .” This goal, he announced, had been met, and, offering some selective evidence, remarked that “the English and Spanish languages mingled as they have never been mingled before. . . .” Other observers echoed the president. The Pan-American fair, said one, has been “a great loving cup from which all the nations of the Western Hemisphere have sipped.” Chile had traveled seven thousand miles to take part in the big show, and Peru, Ecuador, Honduras, and Cuba had joined in “as if the Spanish language never existed.”

Given the many translators necessary for speeches throughout the season, the Spanish language seemed alive and well. But the “Pan American movement,” as Milburn and others called it, in which Latin American republics opened themselves to investment and trade, and the United States took the lead in development, was considered well begun. It wouldn’t be an American empire in the sense that the Philippines had now become part of an empire, but it wouldn’t be far off, either.

Sounding like their old optimistic selves, local newspapers took up the beats of praise. Not only the country, but whole continents now held the city in esteem. The Pan-American had placed Buffalo “among the great commercial centers of two continents.” Even more than that, the Exposition “has caused the eyes of the world to be fixed upon the Queen City.”The magnificent Pan-American Exposition had even made Buffalo “on many occasions shine as the center of the universe.”

It was early June all over again.

Pleas for help from Washington found a sympathetic ear. On the same July day that the Goddess of Light lost her noble perch, the United States Congress passed a relief bill giving $500,000 to the Pan American Exposition Company. John Milburn’s months-long appeal had resulted in a whittling-down of the requested amount, but the money would help. Now, finally, the contractors who had cleared the grounds, built the Exposition halls, and prepared the grounds would be paid. Buffalo had other New Yorkers to thank for the rescue money. In the final vote in Congress, New York legislators had stood up for their western counterparts and “fought for Buffalo like Trojans.”16

VI

MCKINLEY’S GHOST

The make-believe world of Rainbow City, with its minarets and arcades, its starry lights and luminous colors, did not last. It was not remade into an amusement park or a historic site, or turned into majestic gardens. Some bits of it, though, had a second shot at life. The floor of the Temple of Music, where the president had been attacked, was sawed up and stored in an office, and officials announced it would go to a museum. Bostock’s big animal stage became a dance pavilion. The Exposition Hospital, although picked apart by souvenir hunters, was turned into a storage area for the wrecking company. In a reception area near where surgeons had treated the injured president, between seven and ten workhorses were housed temporarily, along with their troughs and feed boxes.

A more elegant future was in store for the New York State Building. Marbled and columned, more reminiscent of Chicago’s neoclassical White City than the Spanish-style structures of the Pan-American, it became the permanent residence of the Buffalo Historical Society. Within its archives stand vast records of the Exposition, including, on a sturdy shelf, Mabel Barnes’s record of her thirty-three trips to the fair. Her neatly penned and decorated homage to Rainbow City, in three volumes, took her from 1905 to 1914 to complete. Mabel continued to serve Buffalo schools, first in the classroom and then for thirty years as a librarian. She died at the age of sixty-nine, in 1946.17

The men who had led the Exposition and fought for it in the throes of crisis went separate ways. William Buchanan, director-general, continued to represent the United States in Latin American affairs. Fondly known as “the diplomat of the Americas,” he brokered discussions and agreements in Argentina, Panama, and Venezuela. He continued his work in international business enterprises as well, marketing free enterprise to his friends in the Southern Hemisphere. His family was still living in Buffalo, and he was actively involved in diplomatic work in London in 1909, when, at age fifty-seven, he abruptly died. His body was shipped back to Buffalo for burial, and Pan-American officials served as his honorary pallbearers.

Buchanan’s partner in Rainbow City, John Milburn, tried to return to some level of normalcy in the fall of 1901, but it wasn’t easy. Even after attendants removed oxygen tanks and electric fans from McKinley’s sickroom on the second floor of his home, Milburn contended with reminders of the president’s death. He now lived in the most famous house in Buffalo. Souvenir hunters took stones from his driveway and leaves from his trees. “Kodak fiends” surveyed the house from every angle. One man brought a chisel to the site to take away a few bricks. Touring coaches also stopped outside and guides used megaphones to identify the windows of the room where McKinley breathed his last. Some sightseers even asked to be admitted to the house.

In 1904, Milburn left Buffalo for New York City, where he carried on as a high-profile lawyer. He served as counsel to the New York Stock Exchange, and as a director of the American Express Company and the New York Life Insurance Company. He moved to an estate on Long Island, where his sons continued to play polo. Like his Pan-American cohort, William Buchanan, John Milburn died in London. It was 1930, and he was seventy-nine. His house on Delaware Avenue was torn down in the late 1950s.

Conrad Diehl had had enough of mayoring by the end of 1901 and left office just after the Exposition closed. Some said he was devastated by the death of McKinley—a painful blow to his treasured project. Diehl’s time as mayor was marked not only by planning and hosting the Exposition but also by bringing electricity from Niagara Falls to operate streetcars and city lights. He also had to cope with a treasurer who ran away with more than $40,000 in city funds. After years of dealing with rich Buffalo businessmen, Diehl moved back into more comfortable work as a doctor and returned to his large practice. A robust man who had almost never been ill, he proved he was mortal on a stormy night in February 1918, when he slipped on ice during his evening walk and died a week later. “The Father of the Pan American,” who was also known as “The Beloved Physician,” was seventy-five years old.18

The man who was made President of the United States in Buffalo, Theodore Roosevelt, established one of the most energetic presidencies in American history. Pursuing some of the same concerns he had announced when he first set foot in the Temple of Music in Rainbow City, he attacked corporate wealth. He continued to promote the doctrine of manliness, as well as the well-being of Anglo-Saxons. He embraced Latin America, as long as Latin America did not engage in “chronic wrongdoing,” and when it did, he embraced sending in the United States Navy to sort things out. (This policy, the Roosevelt Corollary, justified sending US troops to Latin America more than thirty times between 1898 and 1930.)

Roosevelt was also known for land conservation. Echoing the themes of the Pan-American Exposition, he asserted in 1908 that “America’s position in the world has been attained by the extent and thoroughness of the control we have achieved over nature.” But to maintain this position, and to encourage the out-of-doors hardihood he championed, he believed that wilderness—forests, mountains, and waterways—needed to be protected. As president, Roosevelt created game reserves, bird refuges, and national parks, altogether setting aside 230 million acres of land.

Roosevelt likely took many lessons from his days at the Buffalo Exposition, but embracing personal security was not one of them. He made a point of striding about Buffalo in the wake of the shooting, waving away worries about his safety. Six years later, on New Year’s Day in 1907, he set a record by shaking hands with 8,105 people at the White House. Five years after that, his confidence, or faith in his constituents, or both, almost proved fatal. On October 14, 1912, while campaigning (unsuccessfully) in Wisconsin for a third term in office, he stood up in a carriage to greet a well-wisher. Another man took advantage of his exposure and shot him point-blank in the chest.

Roosevelt’s folded campaign speech—it was a long one—helped shield him from a deep bullet wound, and he went on with his lecture. Even as his chest bled and his voice weakened, he persisted in talking. Only later did he agree to an X-ray, which showed a bullet in one of his ribs. It was never removed. John Schrank, the man who shot Roosevelt, claimed he had been inspired by a dream about William McKinley, who had appeared to him as a ghost and had spoken to him from his coffin.

The speech the wounded Roosevelt gave that night in Wisconsin had more than one echo of the shocking event in Buffalo. While continuing to remind his audience that he had been shot, and that he was all right, and that people could not use his injury as a chance to “escape” his speech, Roosevelt talked about what might have stirred up the would-be assassin. He blamed the “daily newspapers,” with their “mendacity and slander which . . . incite weak and violent natures to crimes of violence.” But he went further than that. “The incident that has just occurred,” he said, signaled an ominous trend in America, where, if nothing was done, “we shall see the creed of the ‘Havenots’ arraigned against the creed of the ‘Haves.’” If that day arrives, he said, shootings such as the one he just suffered would happen again and again. “When you permit the conditions to grow such that the poor man as such will be swayed by his sense of injury against the men who try to hold what they improperly have won,” he concluded, “it will be an ill day for our country.”

After William McKinley had been killed, no politician would have dared to make such an assertion. It would have sounded disrespectful, unpatriotic, and radical. It would have sounded too much like Emma Goldman, who, in response to McKinley’s assassination, had suggested that Leon Czolgosz’s violence was a result of “conditions,” and explained that “there is ignorance, cruelty, starvation, poverty, suffering, and some victim grows tired of waiting.”

Theodore Roosevelt did not readily champion the causes of working people. He worked from the top, not the bottom, targeting concentrated wealth held in trusts, banks, railroads, and corporations. Through his actions, though, and in rare speeches like this one, he did more than most presidents to address the inequalities of wealth at the turn of the century.19

Roosevelt never forgot to be kind to Ida McKinley. He sent wreaths to be put on her husband’s tomb on Memorial Day and apologized if he went through Canton and did not stop to see her. For her part, Mrs. McKinley submerged herself in grief. She visited her husband’s cemetery vault daily, cared for the fresh flowers that arrived, and wept. Edith Roosevelt, the new first lady, occasionally sent flowers to the site, and Ida McKinley sent them back after they had withered. In her house, she knitted slippers for charity and ate meals in silence. A friend visiting in 1902 said that the house, with its stale air and dead quiet, seemed like a “cemetery,” and that its resident looked forward to her own death. “I only wait and want to go,” Mrs. McKinley had lamented.

Contrary to general expectations, the death of her husband, and the grief that attended it, did not kill Ida McKinley. After several years of unhappy seclusion, she began to emerge. Her health seemed to improve. Her visits to the vault lessened, and she uncovered long-lost passions, such as her support for women’s suffrage. Susan B. Anthony had earlier sent her a four-volume history of the movement, and nurses read the books aloud to her at night. She began to take an interest in theater and relished the company of her grandnieces—one of whom reminded her of her long-lost daughter Katie. In 1907, Mrs. McKinley suffered a bout of the flu, and, shortly afterward, a stroke. She died on May 26, 1907. President Roosevelt headed the government delegation at her funeral.20

VII

THE PROUD QUEEN

The 1900s looked like they would be good to Buffalo. The money that helped build Rainbow City paid for more industry, new blast furnaces and grain elevators and more railroads. The century that began with Buffalo celebrating the subjugation of a waterfall became the century that saw the city succeed in smelting iron ore, as it became one of the world’s biggest centers for steelmaking. The Pan-American Exposition had done its part in honoring the transition when some of its lumber went into the construction of laborers’ homes near the Lackawanna Steel Works. The Exposition also generated dozens of new enterprises and manufacturing plants, and thousands of new jobs. The Larkin Soap Company echoed other businesses when its executives said that exhibiting at the Pan-American had been “the best investment we ever made.”

The Queen City boomed through World War I. During the next war and into the 1950s, there seemed to be no stopping it, as Buffalo’s industrialists contracted to build automobiles, airplanes, ships, engines, and tanks. Some city boosters held onto the idea that Buffalo might match Chicago, even as Chicago spread wider and taller and became more populous. In the late 1920s, local advertisers maintained that Buffalo only needed better branding and more hustle. “Any other place in America with half the natural endowment of the Niagara Area,” commented a local writer, “would be chasing New York for first honors and laughing at the other cities. Look at Cleveland—just a spot on Lake Erie, and not a very good spot, either. Look at Chicago—entirely surrounded by prairie and bossed by bandits—or St. Louis, with nothing from Nature except the stickiest, muggiest climate this side of Sheol.”

More sensible city leaders knew that catching up to New York City or Chicago was a fanciful ambition. Even Detroit and Cleveland had surged past Buffalo in population. Yet they dreamed of greatness, particularly in midcentury, when the booming economy helped Buffalo become a center for modern art, contemporary music, and, thanks to the new state university, cutting-edge humanities. An advertisement produced by the local Chamber of Commerce in 1963 echoed Pan-American boosters. Buffalo was the “port for 5,000 visiting ships of every flag . . . blast furnace for 7,220,500 tons of steel . . . terminal for more than 20,158,555 tons of rail freight . . . manufacturer of products worth $2 billion.” It was “flour mill for the nation” and the “research center of the world.”21

And then there was a fall—a fall so protracted and deep that it made McKinley’s death feel like a bump in the road.

Buffalo, once the grand way station—the famous inland port with grain elevators as imposing as office buildings—became known as a city of rust and struggle. In 1959, a project that had gestated since the 1920s became reality, as engineers completed the Saint Lawrence Seaway, a massive canal that offered shipping companies an opportunity to bypass Buffalo and send their freighters directly from the western Great Lakes through to the Atlantic Ocean.

Thankfully, there was still the power of steel. In 1965, Buffalo produced more than seven million tons of steel at Bethlehem’s Lackawanna plant, and, nearby, factories stamped cars out of the metal.

And then that, too, was gone. Bethlehem Steel, succumbing to the triple challenges of foreign competition, new regulations, and management miscalls, first laid off workers and then, in the late 1970s, fired them. Auto plants closed. Manufacturing jobs withered and died. By the early 1980s, big-muscled Buffalo had atrophied. In April 1983, a Buffalo company advertised for forty workers and ten thousand candidates stood in line. Four months later, the Lackawanna steel mill saw its last day of production. Its workers did not go out without comment, however. In the middle of the night on August 16, they raised the international distress signal on top of a blast furnace. The upside-down American flag, measuring more than five hundred square feet and illuminated by two big mercury vapor lamps, blew its message of defiance out over the lake. It was said it could be seen as far north as Niagara Falls.22

It was in the wake of these losses, and in the face of a diminishing population—Buffalo went below three hundred thousand in 2000—that the city celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the Pan-American Exposition. The university, the historical society, museum curators, city officials, local historians, and enthusiasts of all sorts collaborated to consider the meaning of Rainbow City. They pondered the implications of a fair that, in 1901, had encouraged an interconnected hemisphere. What did the fair now mean in the “global” twenty-first century? How did questions that the fair exposed—about racial justice, economic equality, the American mission, the promise and perils of technology—persist and change? The anniversary inspired a Pan-American Exposition website—with virtual visits to the fair—symposia, exhibits, tours, histories, not to mention a best-selling novel, City of Light, which brought to life some of Buffalo’s best-known characters.

The anniversary, like the Exposition it honored, generated differences of opinion. Did 1901 represent Buffalo’s “shining moment,” as some suggested, or did this sort of thinking dismiss the city’s promise and future? The New York Times weighed in on the debate. In an essay by Randal Archibold announcing the centennial, a headline said it all: “Buffalo Gazes Back to a Time When Fortune Shone: Much-Maligned City Celebrates the Glory of a Century Ago.”

The writer began with harsh words: “It is hard for outsiders to imagine that before the steel mills died, the young people fled, and the Bills choked, Buffalo was unbowed and proud.” He went on: Buffalonians were indulging in “a spate of nostalgia that has become something of a civic obsession.”

If Buffalo was maligned, New York City had, for more than a century, carried some of the guilt. Mismatched as they were, Buffalo and New York had been urban siblings. When opposition came from outside the state in 1901, Manhattan became a fierce protector: helping Buffalo secure the Exposition, helping defend Buffalo against slander after the assassination, and helping Buffalo get funds from the federal government. But, siblinglike, New York City threw punches. In 1901, New Yorkers were accused of seeing the Lake Erie city as a “pretentious little sister” and of not bothering to go to the Exposition “in sufficient numbers.”

Now, some one hundred years later, the belittlement seemed to persist. It wasn’t just that New Yorkers saw Buffalo as a city of past, not future, magnificence, but a Manhattan urban planner suggested in 2010 that it was perhaps time for certain upstate cities to die. Across the Midwest, Mitchell Moss said, state governments had let once-proud cities disappear, and it was time for New York to “do the same.” He chose Buffalo as his example of a city that once flourished, and he used 1901 as his frame of reference.

Buffalo, of course, was not giving up and not going anywhere. It had not given up when it was slammed with an assassination and an insolvent Exposition. It focused on what it had gained and what it had imparted. It had not given up when merchant ships went elsewhere and steel mills failed. It moved forward, reused, and reinhabited. Instead of taking iron ore and making steel, the city began to work at the earth a different way. Along the lake, using roads worn down by steelworkers and grounds flattened by blast furnaces, developers put up wind machines, sentinels of a new age. They planned factories for solar machines. Visionaries, too, reawakened neighborhoods and pulled people back to the core of the city. They turned industrial landscapes into byways and parks and defiantly, boldly, lit grain elevators with flashing colors.

The pride that launched the Exposition in 1901 gave birth to the pride that ushered in Buffalo’s “new beginning” in the twenty-first century. Rainbow City itself, however, mostly disappeared. Buffalo honored McKinley with a ninety-six-foot obelisk, funded by the state, that went up in front of City Hall in 1907. It saw a downtown office building, reminiscent of the Electric Tower, rise in 1912, and it handed the house where a tired Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office to the National Park Service in 1969. With the exception of the New York State Building, however, the 1901 grounds were let go, and, with time, developers seeded them into cropped lawns, put up well-appointed houses, and paved new avenues. Faded plaques mark the locations of some Exposition buildings, and metal tablets tell pedestrians where the president was shot and died, but mostly it is hard to know that, long ago, there stood on the site an enchanted metropolis.23

Other evidence of Buffalo’s fair, on the other hand, lives on. Remnants of Rainbow City, and accounts of those who animated it, sit in museum exhibits and rest on shelves of local libraries. Records also exist, ever so compactly, in virtual archives. Tireless recordkeepers unlock them for us, not only bringing the Exposition back to life but also allowing it to change over time, with new ways of seeing.

VIII

THE TIMEKEEPERS

The spectacle called Rainbow City had been built by people motivated by a love for their hometown and country and, of course, a desire to make money. They were exceptionally proud of their way of life and believed it should be shown off and shared. In their triumphant march to the apex of civilization, they said, they had not only overcome human savagery but also tamed the animal kingdom and, for the sake of modern technology, conquered the natural world.

Rainbow City was not built without opposition, and, particularly in the autumn of 1901, it did not carry on without resistance from performers and members of the public. Animals acted out, too, and even “nature,” like Niagara Falls, and forces, like electricity, took prisoners. The Buffalo Exposition generated modern concerns about the meaning of technology and generated modern discussions about animal welfare. It also spurred talk of social equality and marked the sudden appearance of a modern American president. The Pan-American fair brought the country into the twentieth century with a literal jolt.

There had been other magical exposition cities in the late nineteenth century, and there were more to come. Many echoed the same themes of civilization, nationhood, and globalized trade that had inspired the Pan-American Exposition. All together, they instructed and entertained, and, yes, provoked millions and millions of people.

By the end of the twentieth century, these massive fairs not only dropped in frequency but also shifted shape. While there was little change in the business aims of fairs, and, behind the scenes, corporate capital held its ground, swings in the social tide meant new sorts of displays. Ongoing struggles against imperialism, the civil rights movement, and other efforts for social justice meant a gradual end to displaying “types” of people. Celebrating the subjugation of animals and the planet also lost favor.

Expo ’74, a world’s fair in Spokane, Washington, reflected this fluctuating landscape. At first glance, the Spokane exposition sounded oddly like the Pan-American fair: a city host eager for development and investors, a waterfall as a central feature, and an exposition without a women’s pavilion. But it went in a new direction. Not only did it feature a grand African American pavilion, it also hosted a celebration of the state’s recent passage of the Equal Rights Amendment for women. Most striking was its focus on the environment. While it was accused of being a sellout to commercialism, and it lacked the backing of major environmental groups, it hosted serious conferences and exhibits focused on environmental concerns. The United States Pavilion even inscribed on its central wall a bold new message: THE EARTH DOES NOT BELONG TO MAN. MAN BELONGS TO THE EARTH.24

The Spokane fair, and others that succeeded it, showed us how things had changed since 1901. These expositions were, as William McKinley claimed just before he was killed, the timekeepers of progress. McKinley’s idea of progress—the triumph of big business, the success of the white man’s civilizing mission, the harnessing of the globe—was far removed from the meaning of progress that would prevail for subsequent generations.

But McKinley was right: These fantasylands were telling. Rainbow City, intended as a scripted and neatly schemed production, became an improvised performance—where the rich and the powerful, the poor and the desperate, the human and the animal, and the natural world, in all its beauty and fury, met in dynamic alchemy.

It was the supreme measure of a moment in time.