I

THE MENAGERIST

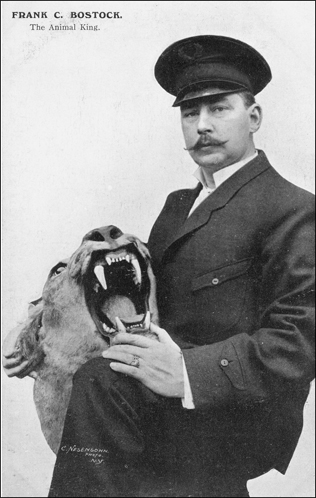

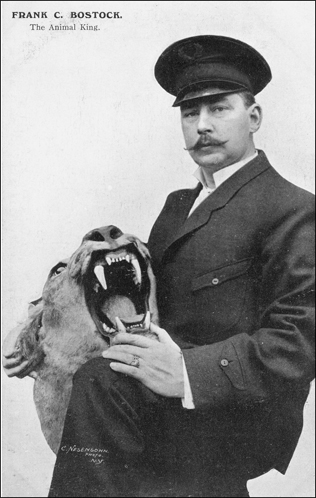

Just thirty-five years old in 1901, Frank Bostock looked the part of a ringmaster. Often in uniform, he stood six feet tall. His eyes sat small and high in his white face and he wore his mustache in a wire-like swirl. In 1899, when he had applied in person to bring a wild-animal show to Rainbow City, Bostock touted his experience and made big promises. He boasted about his background, which included growing up in a family of animal trainers in England and marrying into the Wombwell family, owners of a world-famous zoo. He had successfully shown his trained animals in Europe, he said, and had staged several exhibits in the United States. Now, he told officials, he would bring a veritable jungle to the Pan-American Exposition. On a large plot of land, he would plant trees and bushes and bring up to 150 lions to “roam around it at their will.”

As intrigued as they might have been, Buffalo directors told him to wait. Carl Hagenbeck of Germany, the world’s best-known animal trainer, also wanted a place on the Pan-American Midway, and they could offer only one contract. Some directors thought that the experienced German would do a better show.1

Bostock needed the job—badly. He had had success with his animal zoos in the United States but hadn’t broken through to the big time. And it is not clear whether he could go back to Britain. His brother ran a major animal show in Scotland and would compete with him. Furthermore, he had left London under a shadow. In the early winter of 1893, British papers reported that Bostock’s wife, Susannah, had charged him with theft and cruelty. She alleged that he had sometimes left her and their children with no food, and that he had struck her. To top things off, she said, he had recently abandoned the family, departing for Europe with the eighteen-year-old daughter of a friend.

Bostock answered the charges. He admitted he had left with the girl, and that he had taken some jewelry and silverplate belonging to his wife, but “afterwards he had sorted them out.” As for the hitting, he had indeed struck his wife, “because she was drunk, but he was extremely sorry and made it up with her.” When Susannah confessed to drinking, the charges against the menagerist were dropped.2

Frank Charles Bostock.

After reuniting with his wife and children, Bostock traveled to the United States and started business anew. Stories of his domestic problems did not travel with him; nor did the charges of animal cruelty that occasionally appeared in British police records. Instead, the showman disseminated press accounts that stressed his kindness. There wasn’t even much of a fuss when, in the spring of 1900, a reporter who went to see Bostock’s lion school in Baltimore discovered signs of rough treatment. He noted that it seemed “necessary to lash [the young lions] severely,” and that Bostock’s trainers used a long whip with “stings.” The reporter also saw that obstinate cubs went without food if they balked at posing for tableaux, and they were only willing to jump through a hoop of fire if they were first cornered, then frightened, by the sound of a gun.

Even if they had read this account, members of the public might not have been bothered. Such training might have seemed more like discipline than cruelty. In Buffalo, the one person who might have been alarmed was Buffalo’s mayor, Conrad Diehl. Throughout his public life, the physician not only had championed the needs of sick and poor people but also called attention to the suffering of animals, particularly city dogs. Mayor Diehl, however, had little to do with the hiring of Midway acts.

The choice of a wild-animal show for the Pan-American fair dragged on. Through the summer and fall of 1900, Director of Concessions Frederick Taylor held meetings about Hagenbeck and Bostock behind closed doors, and he refused to comment. Meanwhile, Bostock pumped up the charm. He reappeared in the Queen City twice in 1900, bringing with him enticements such as Chiquita and suggesting new performances. He proposed building a spectacular circular lion cage and acting out “Daniel in the Lion’s Den.” He himself would play Daniel. The Pan-American Exposition, he predicted, would be “the largest ever held in Europe or America.”3

After he got the job, Bostock applied the same marketing skills to his show that he did to selling himself. His wild-animal arena was one of the first concessions to open in Buffalo in May, and his press agent announced it as the “star feature” of the Exposition. Mirroring the themes of human conquest that the fair trumpeted elsewhere on the grounds, the agent claimed that the Animal King ruled over a vast domain. He had conquered the natural world to assemble his collection, having invaded the “jungles of Africa, the forests of India and the deserts of Arabia and Egypt.” He had gone on to “ransack” ice floes and frozen seas. Not surprisingly, he not only had triumphed over other “animal subjugators,” but he also had overpowered indigenous peoples wherever he went: “The savage natives of the globe’s remotest corners and most inaccessible recesses know of the white man who rules the most ferocious beasts into absolute submission and obedience by some mystic power they cannot understand.”

Bostock’s trained animals seemed the perfect match for the Exposition’s pronouncements about race. One of Bostock’s monkeys was linked to American foreign policy in Southeast Asia. Mike, a small orangutan from the Philippines, couldn’t comment on the war in the Philippines, noted a bystander, but “he is of peculiar interest because, in some respects, he resembles the creatures we are daily filling with Maxim bullets and shells. . . .” The showman’s celebrated chimpanzee, Esau, was alleged to be “the missing link” and a member of a group of ape-men recently discovered in Uganda.

Press offices admitted that Bostock’s charming publicity agent, Captain Jack Maitland, had them cowed. Maitland’s releases, one reporter admitted, were often sent directly to the composing room. “It doesn’t make a bit of difference what the press agent writes about or how much truth there is in it,” he said, “so long as the matter is published and the name of his employer or his show appears.” When business becomes dull, he added, “it is positively wonderful to see how the captain’s imagination comes to the rescue. The next day the papers contain a startling story of a fight between lions or an animal getting loose with the narrow escape of the employees. An inquisitive public flocks to see the ferocious beasts and the victory of the captain is complete.”

Bostock added to his mystique by staying behind the scenes. When he did make an appearance, it was rarely without an animal on his lap, and usually in the company of his bodyguard, a six-foot-tall former major in the Bombay infantry. Turbaned, and of a “mighty athletic build,” the guard had reportedly hunted and killed up to a hundred tigers.4

As popular as his show proved to be in Rainbow City, the Animal King had his troubles. At the end of June, a Bostock trainer, Herman Weeden, suffered a nervous breakdown. Weeden had returned to work after a tiger attack—too soon, it turned out. He began hallucinating. One evening he imagined that he was Bostock himself, and, wielding an imaginary whip, flew around his quarters in a frenzy, trying to subdue phantom animals. “Look,” he shouted, “I am the animal king. I am the monarch of the brute world.” Bostock, endeavoring to placate Weeden until an ambulance arrived, played the part of a lion, crouching on all fours.

Animals line up in front of Bostock’s arena. The large elephant in the center is likely Big Liz, who befriended Jumbo II.

Although Frank Bostock could manage the temporary loss of one of his trainers, he wasn’t so sure whether he could get along without his Cuban Doll. Sometime in late June, one of his employees reported to him that Chiquita had a growing attachment to Tony Woeckener, a young cornet player in her show. Bostock was enraged. Chiquita, he felt, owed him unwavering loyalty. He had befriended her, supported her, managed her, taken her into his home. He had provided her with jewels, dresses, furs, tiny carriages with tiny horses, and even a car. He had made a lot of money with her, to be sure. But how dare she? The Animal King was nothing if not resourceful. It would take only a few small lies and, if that didn’t work, a lock and key.5

II

THE CUBAN ATOM

The journey that had brought Chiquita to the Pan-American Exposition and placed her under the strong arm of Frank Bostock spanned at least three countries. Before she became the Doll Lady, or the Cuban Doll, or even Chiquita, she was Espiridiona Cenda, born in Guadalajara, Mexico, around 1878. We do not know whether her birth was attended by any cries of surprise, but it was reported that when she entered the world, she was eight inches long, three inches wide, and, when doubled up, the size of “a large grape.” More impressive than her size, apparently, was her proportionality. “Nearly all midgets have some deformity,” the Buffalo press would explain, “something freakish in their appearance, but this little woman is one of the very rare exceptions.” As her managers would claim, she was “a perfect living, breathing doll.”

Alice Cenda, as she was known offstage, attended school in Mexico and trained in singing and dancing. When she was about fifteen, her father hired a manager to exhibit her to the public, and she toured widely in the country, and later throughout Cuba. Sensing profits in using her as an emblem of the island, one of her managers reinvented her as Cuban and brought her to New York. Two brothers came with her.

In New York, in 1895, Frank Bostock—who later would say he found her as a “Mexican peasant”—took over her contract. He paid her $80 per month for her performances (and held onto her money) and brought in, by one account, $1,000 per week. By 1900, she had become one of Bostock’s main attractions and toured in the United States and Europe. Like so many other Little People in show business at the time, she met heads of state and royalty.6

In establishing Chiquita as one of his big acts, Bostock joined the swelling numbers of American freak-show promoters. Human “oddities” had been put on display for generations, but they reached their peak in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, with the advent of shows like P. T. Barnum’s, and with touring circuses and fairs. Individuals with extraordinary bodies were fascinating to a culture obsessed with classifying, measuring, and establishing standards and norms. So much appeared in flux in American society at the time that spectators looked to disabled people for reassurance that there were limits to fluidity. People such as beleaguered urban laborers or immigrants or the rural poor—those who commonly attended the shows—were reassured that they had one attribute—the shape or size of their bodies—that fit an ideal. The most popular acts were those like Chiquita’s, which featured people of non-European ancestry.

Alice Cenda, aka Chiquita, in the late 1890s.

Buffalo audiences took to the Doll Lady with enthusiasm. They enjoyed her singing and dancing, her “quaint” accent, and her stories about meeting monarchs such as Queen Victoria. Like Mabel Barnes, they also enjoyed shaking her tiny hand. Not only did Chiquita sell a lot of tickets, but, on July 10, Director-General William Buchanan christened her “The Mascot of the Pan-American Exposition.” It seemed a fitting title. The little “Cuban” was a perfect symbol for what the United States sought in its relations with Latin America—and with the island nation in particular. During and after the war with Spain, the American popular press had pictured Cuba as a charming daughter to Uncle Sam, eager for his aid and protective oversight. Chiquita, who exhibited “the charm of manner so characteristic of her race,” and who could “sit with ease and comfort in the hand of any grown adult,” seemed the perfect embodiment of this thinking.

Chiquita performed her part perfectly. She spoke out about the Cuban fight for liberation, and was given special authority to do so. As early as 1896, the press announced that she had been born into an established family in Cuba’s Matanzas province and that Spaniards had torched her family’s home and sugar plantations, and put her to flight. With two of her brothers in the army of Cuba libre, she was “a little rebel every inch of her 26 inches and she hates everything Spanish with the hatred of a loyal daughter of Cuba.”

During the winter of 1901, Chiquita had even become friends with the chief architect of America’s Cuba plan, William McKinley. On February 13, dressed in diamonds, silk, and satin, she had been carried up the White House steps into McKinley’s office. “I want to thank you,” she told the president, “for all that you have done for my people.” McKinley, delighted by her speech, unfastened a pink carnation from his lapel and pinned it to her dress.

Chiquita may have personified the hopes of American policymakers, but she was neither as compliant nor as needy as her size suggested. Nor was she as dainty as her act implied. While she had domestic talents, especially in embroidery, she was also a spitfire of spunk and nerve. She played a hard hand of poker. She put up “a pretty stiff little bluff on even a ‘bob-tail flush,’” claimed one reporter. And he suggested that it wasn’t just the card game. She didn’t want to be treated like a toy in any setting. “Perhaps nothing so well illustrates her dislike for being regarded as different from other people,” he commented, “as the fact that she objects to a high chair at the table even though her little chin comes only to the edge of her plate . . . but she suffers the consequent inconvenience to herself because of her pride . . . she wants it understood that she is not a doll.”

Bostock’s Main Attractions.

But Bostock liked her as a doll. Even though the showman was just over a decade older than Chiquita, she called him “Papa.” While on tour, he gave her sleeping quarters with his children and encouraged her to take meals with them. He sometimes seated her with a different dining companion, too—Esau, the trained chimpanzee. Esau wore human clothes, slept in a bed, walked erect, and played the piano. He was also “learning to talk.” Bostock liked partnering brown-skinned Chiquita with the monkey so much that he double-billed them as the two main sideshows of his zoo.7

Chiquita’s friend Tony Woeckener was, by all accounts, small for his age. Not Chiquita small, but short and slight enough that people called him “Little Tony” and said he looked at least two years younger than he was, which was seventeen. The earnest, open-faced teenager, who kept his hair in a determined part, played the cornet outside Chiquita’s reception hall, helping to lure fairgoers into her show. He had first met Alice, as he called her, in 1900, in Atlantic City, when he and his family—seven musicians in all—had been hired by one of Bostock’s shows. “She looked at me and smiled, and I smiled back,” Tony remembered later. “She heard I sang, and . . . I did sing, and that was the beginning of the love affair.”

At Buffalo they grew closer. “About two weeks after the big show began,” Tony recalled, “I was sitting with her in her dressing room. A pretty warm friendship had sprung up between us. . . .” He decided to ask her to be his sweetheart. Alice said yes.

They tried to keep their affection for each other a secret—from Bostock, from the other showmen, and from the public. Tony surreptitiously brought over dinner after her show ended for the day, and they spent time together, quietly. “I taught her to write English,” said Tony. “She taught me some Mexican.”

They knew they risked discovery. They were well aware that when the Animal King found out about their liaisons, they would suffer. And sure enough, one day at the end of June, one of Bostock’s men witnessed something, or heard some gossip, and carried the news to the boss.

Frank Bostock didn’t just fire Tony; he let a rumor circulate that Tony had almost destroyed Chiquita’s whole concession. The musician, he claimed, had broken an expensive calcium light and nearly started a fire. Tony, he clearly hoped, would have a hard time finding a new job.8

III

THE VANISHING STATE

By July, most people in the city of Buffalo had been swept into the whirl of the Exposition. Even those far out of town did not escape. The Electric Tower sent its searchlight across the dark river to Canada, and the percussion of fireworks carried so far through the humid air that even farmers in the hinterland felt the thumping celebration.

Word of the fair’s magical lights, colors, and Midway was also carried across the country, in nearly every newspaper. It made its way into the New York World, and, from there, into the hands of the World’s curious readers. One of them sat in a rocking chair in a small house in a Michigan town on Lake Huron. Down on her luck and discouraged, Annie Edson Taylor read about the crowds gathering that summer in Buffalo and in nearby Niagara Falls. Suddenly—she felt nearly blinded from the shock—she was struck by one of the strangest ideas imaginable. She had thought of a miraculous way to pay her bills. She would take advantage of the throngs and do something so startling and extraordinary that fame, fortune, and a happy future would be assured.

Sometime later, and quietly—she did not want to share her plans—she gathered cardboard, cut it in strips, and sewed the strips together. Then she stepped inside. She had designed herself a barrel. What she would do with the barrel was drop herself 160 feet over Niagara Falls. If she lived to tell the tale, she would become an Exposition sensation, perhaps even a sensation for life. No one had ever survived such a descent.9

Even as Annie Taylor learned of the Pan-American’s big crowds, Buffalo itself began to fret. World’s fairs were put together by individuals—businessmen, publishers, politicians, clubwomen—but quickly they became a referendum on a place, a place that, as time went by, seemed increasingly human. Buffalo struggled for recognition, approval, and a public pat on the back. And it sought to make a lot of money. As June days edged into midsummer, fair investors and directors infused their pride with worry and began to take measurements. How many clicks had the turnstiles recorded? Of the nearly forty million people who lived within a day’s journey, how many were making the trip to the city? Who had written glowing words about the show? Who had been critical? Ticket counters realized that Omaha’s numbers were being surpassed at the Pan-American, but not easily. Chicago’s exposition, that king of fairs, seemed to be pulling out of reach.

Local editors picked up the concern and tried to help. They printed every scrap of praise, no matter how lukewarm or hyperbolic. In the middle of July, they announced that construction of the fair was finally finished. They claimed that Rainbow City was cleaner and neater than other fairs. (It featured asphalt, of course, so there was very little dust.) And they boasted that while Pan-American visitors enjoyed breezes off the lake, New York City was “sweltering, Philadelphia lies languid . . . and Chicago’s list of heat prostrations grows.”

Exposition officials did their part. They cut the price of admission on Sundays from fifty cents to twenty-five cents to attract working families. And they looked to special “days,” when the fair honored particular groups or states or countries, for increased attendance. Sometimes they assigned three groups to one day to triple the chances for a big turnout. July 24, for instance, served as YMCA Day, Utah Day, and Knights of Columbus Day.

This strategy worked—sometimes. Utah Day arrived, but Utah, it seems, couldn’t make it. Visitors to the Exposition looked in vain for displays of Utah’s produce, manufactures, and art and literature. They looked for the Utah Building and for people from Utah. Not surprisingly, they looked for Mormons with multiple wives. And they looked for the man who had proposed Utah Day in the first place. Apparently, even he had left town. One reporter described a frustrated visitor who had once lived in Utah, circling the entire Exposition for signs of his former state. Footsore, he sat down on the steps of the Ohio Building as the sun began to set. “Where in the name of Christendom is Utah?” he muttered.

Slow days were indeed a puzzle. Why were the numbers off? Was it the fault of the railroads? Were the fares off-putting? Was the advertising weak?

People wondered whether it was a mistake not to have had a special place where all women were welcome to gather. The Women’s Building, a veranda-wrapped house at the southern entrance of the grounds, was intended mostly for private use. The headquarters of the Exposition’s women managers, it held meeting rooms for clubwomen, college graduates, and women of other “leading” organizations. There were no “women’s” exhibits in the building, and not many more in the rest of the fair. This, the Board of Women Managers insisted, signaled progress.

Chicago, some murmured, had done things differently.10

Fair directors also wondered to themselves whether the theme of the fair had anything to do with slow attendance. Perhaps the focus on the Southern Hemisphere had been a risky decision. Middle-class Americans were unabashedly dazzled by Paris, London, Vienna, and Venice. In school, many of them learned the histories and languages of Europe and, if they had enough money, they toured Europe. At expositions, they admired European exhibits. In Chicago’s White City, they paid to see French pavilions, German imperial treasures, and Elizabethan architecture. Director-General Buchanan remarked that limiting displays of industry and manufacturing to the Americas had perhaps “weakened to a degree general interest in the exhibits.”

Exposition planners had known from the beginning that many of their potential guests held unflattering and poorly informed opinions of Latin American republics. “It is astonishing to learn,” commented the Exposition’s director of publicity in 1899, “that a very great percentage of the better educated classes are almost entirely ignorant of the wealth of the [South American] countries.” A prominent businessman he knew confessed that he associated the name Buenos Aires with images of “dusky natives clad in jaguar hides.” The publicist pointed out to him that the cosmopolitan Argentine capital had plenty in common with Paris.

The press certainly played a part in assigning second-class status to Latin America at the Exposition. It billed New World exhibits as exotic and romantic, and let loose a barrage of backhanded compliments. Argentina demonstrated “marvelous growth and progress.” Chile, which had spent $500,000 on its Buffalo building, was described as “progressive and highly advanced” and was commended for having sent its young artists to Europe for training. Then there was Mexico, which showed “wonderful advancement,” and Cuba, the “little American isle,” ripe for investment.11

IV

MIDWAY DAY

Whatever the reason for slow ticket sales, Midway men were ready to tackle the problem. They knew that visitors to Rainbow City sometimes bypassed big exhibits on machines and art and history but rarely, if ever, missed the Lane of Laughter. The director-general might make all the noise he could about edifying the masses with grand buildings, but they knew—Chicago had taught them this—that a midway could make or break a big show. What the Exposition needed was a Midway Day. Let the misfits, the animals, the clowns, the “foreign” people take over the whole show. “You’ve got to be tawdry,” said one concession owner, when asked how to sell tickets.

Exposition officials agreed, and on August first they sent marketing men to the railroad offices to get special rates. They hired a hundred girls to accost strange men on city streets and pin satin ribbons to their lapels: “Midway Day, August 3d, Pan American.”12

Two days later, the sun shone, the winds off the lake blew cool, and the crowds materialized. Pennsylvania and Ohio trains had to order extra coach cars, Rochester’s platform was packed with fairgoers, and, on Buffalo streetcars, people sat on laps and stepped on toes. On the grounds, animal trainers rose early to wash elephants and grease camels, and performers dressed themselves in furs, feathers, grass skirts, and paint.

It was late morning when the parade began. Like a serpent nosing into forbidden territory, Midway floats edged into the Esplanade, then onto the Main Court, where visitors waited, fifteen to twenty deep.

Members of the Carlisle Indian band, with their bright red uniforms and brass instruments, led the way, along with concession managers. Calamity Jane and Geronimo followed, then a band of Apache, and other warriors on foot and on horseback. When Calamity Jane’s mules were jostled by an Indian chief, a spectator shouted: “Teach him to talk English, old girl!”

Chiquita, in a yellow brougham pulled by a miniature pony, led the Bostock concession. The Animal King, pushed by an attendant, sat in a bicycle chair with a tiger cub on his lap. Behind him, his bodyguard, the Indian, followed closely. The elephant Big Liz carried adults on her back, and smaller elephants bore children. A polar bear padded by, then a grizzly bear.

The crowd sent up a roar at the sight of the string band from the Filipino Village. The Igorrotes rode water buffalo and towed their children in oxcarts. The audience whooped its approval, too, at the armed Moros and Tagalog soldiers, the “little fighters” who had just helped oust Spain from the Philippines. One observer noted that these men could certainly use the military know-how of the United States. The Tagalog fighters were “armed with old fowling pieces, blunderbusses and muskets which looked as though they had been handed down from father to son for generations.”

Of all the floats that wheeled by, none provoked as much glee as the Old Plantation’s watermelon. Fifty feet long and fifteen feet wide, the watermelon had a rind as “green as the sea and its core [was] as red as a bullock’s heart.” One witness could barely contain himself: “The seeds—prepare to laugh—the seeds were the heads of live darkies sticking out with a grin on as broad as the sunset over Tierra del Fuego. Yah, yah, yah, they laughed and their teeth shone and their eyes glistened.” Behind the float, one hundred other Old Plantation actors performed the cakewalk. “All of them,” said the spectator, were “as gorgeous and gay as a stalk of hybrid hollyhocks.”

The Indian Congress parades along the Court of Fountains. The Electric Tower rises in the background.

A band struck up “Dixie.” The crowd gave a cheer and joined in, swaying to the song.

The parade wound around the Court of Fountains and reentered the Midway. But before it did, an enormous elephant reached his trunk out to the crowd and plucked a hat from the head of a boy. With a cannonlike snort, he fired it in the direction of the Electric Tower. The crowd howled.13

Jumbo II had arrived in Buffalo in the third week of July. Shipped in a box with his head barely visible, the elephant had been pulled uptown by thirty horses and rolled into the Exposition grounds with fanfare. Jumbo carried a romantic history—Bostock made sure of that, and he and Captain Maitland had been bragging about it for days. Although some people might have suspected—especially if they read New York City papers—that this was the same Jumbo II that had been captured as a baby in India, raised in Germany, and unloaded onto Brooklyn docks in 1900, they were informed otherwise. This elephant, said to be twelve feet tall with a weight of nine tons, had a much more compelling résumé. Once known as Rustin Singh, he had been the valued possession of an Indian prince. As a gesture of goodwill, the prince offered him to the Duke of Edinburgh, but he was too big to travel to England. Instead, he served in the British-Abyssinian campaign, and, along with nineteen other elephants, hauled mountain batteries to the front for Lord Roberts and Charles Merewether. At the Battle of Magdala, he was wounded but labored on, and when other elephants threatened to break rank, his trumpeting kept the herd together. For his valor, Rustin Singh had been decorated by Queen Victoria and “pensioned for life.”

Jumbo II arrives in Buffalo.

By some miracle, the same animal now stood before the admiring crowd in Buffalo. Bostock claimed he had staged a coup. London had wanted the elephant, he said, and members of Parliament had been shocked that the “historic beast” had slipped away. The director of Regent’s Park Zoo, responding to London’s indignation, had just cabled Bostock to name a price to have him sent back to England.

Bostock held onto his prize. He renamed the elephant Jumbo II—commemorating the world-famous Jumbo who had died a decade and a half earlier—and brought him to Buffalo. The new elephant had a rough time of it at first. His stall wasn’t big enough, and he seemed to be lonely. He thrashed in his pen. He also seemed more timid than expected; he was afraid of thunder. But after a few weeks he settled down and made friends—close friends—with Bostock’s other large pachyderm, Big Liz. They had begun to trumpet to each other. And today, on Midway Day, he was the life of the party.

Among the floats in the Midway parade as it moved into and out of the Court of Fountains, was Lubin’s Picture Machines. Spectators were asked to stay still as Lubin’s big camera clicked past them, shuttering open and closed. Mabel Barnes was probably photographed. She had met friends and cousins at the East Amherst gate, and, after navigating through the thick swarms, had watched the parade from the Tower Bridge. Fred Nieman may have been captured on film, too. The family he lived with said he came into Buffalo like clockwork. They didn’t say whether or not he took his revolver with him. He kept one, apparently, in his bedroom.14