I

RITES AND PASSAGES

The Exposition remained closed from Saturday, September 14, until Monday, September 16. A man who walked through the grounds said the only sound he could hear was hammering, as one exhibitor after the next nailed up portraits of the dead president.

On Sunday, the city that had ten days earlier been dressed in starred-and-striped bunting stood sheathed in black crepe. At midday, ebony-colored horses pulled William McKinley’s coffin four miles from the Milburn house to Buffalo City Hall. Ahead of the hearse, a band set a melancholy rhythm to Chopin’s “Funeral March,” while, behind it, Civil War veterans, gray and unsteady, marched to honor their comrade. As the procession passed Trinity Church, choirboys emerged to sing “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” McKinley had uttered the hymn, or tried to, just before he died.

The cortege arrived at City Hall just as clouds driven by a southwest wind off the lake unleashed a downpour. Sailors from the battleship Indiana and soldiers from the Seventy-third Company, Coast Artillery, who had been so much a part of the president’s time in Buffalo, carried the casket into the building, set it down on a catafalque, and opened it. William McKinley lay on a silk pillow, his face under glass. His left hand, which had slipped off his chest during the trip downtown, was repositioned. One observer thought that his face was somewhat sallow, but that all in all he was only a little “emaciated.”

President William McKinley lies in state, Buffalo City Hall.

From early afternoon until late at night, mourners, smelling of wet wool and dripping water, shuffled in two by two and passed the bier. The new president and the cabinet paid their respects, along with politicians and businessmen. The guiding lights of the Exposition came too, as did commissioners from Latin America. And the people came, many from Erie County but others from Cleveland and Pittsburgh and New York. And the Midway came—Bedouins in “Sahara costume,” and more than a hundred members of the Indian Congress. A note, said to be from Geronimo, sat next to a wreath of purple asters. “The rainbow of hope is out of the sky,” it read. Geronimo himself walked through the rotunda with other Apache, as did Lakota, including Red Cloud and Painted Horse. Shot-in-the-Eye, who had been at Little Big Horn and had seen the end of George Armstrong Custer, joined them.

And Jim Parker came, wearing a wide black armband. People murmured as they recognized the tall man and watched him bend low over the coffin to have a long last look. Parker had not been able to shake the hand of the president nine days earlier, but he was at least able to honor him now.1

William McKinley’s body left Buffalo as the man had arrived, by train. At 8:30 Monday morning, September 16, five funeral cars, including a glassed-in observation car carrying the casket, rolled out of town toward the nation’s capital. The train moved southeast, threading its way from New York into Pennsylvania, where it picked up the Susquehanna, and headed into Maryland. Miles and miles of mourners waited along the railroad bed: laborers and housewives, schoolchildren and office workers. Farmers, silhouetted and still, stood in their fields like cairns against the sullen sky. People had strewn flowers on the track—roses and asters and violets—and, as the cortege rolled past, they sang hymns and rang church bells. It wasn’t enough to see or try to photograph the train; a few of the crowd, mostly young boys, put coins on the rails, so that they could forever feel the weight that flattened them.

Ida McKinley traveled in the second coach, alternately resting and staring out the window. Once in a while, especially when she caught the sound of a hymn, she would begin to weep. The new president and his advisers rode along as well, and, in a tribute to Buffalo, four city leaders, including John Milburn and Conrad Diehl, had been asked to join the group, and were part of the funeral services from start to finish.

After ceremonies in Washington, where McKinley lay in state at the Capitol and tens more thousands wound through the streets to bid him good-bye, the entourage journeyed back to Ohio. This time, the train traveled after dark through coal country, past mourners warmed by bonfires, and miners, their headlamps lit, standing bowed. Near Pittsburgh, people on a bridge tipped three wagons’ worth of flowers onto the tops of the funeral cars. By the Allegheny River, men and boys hung onto bridge girders to see the train pass. Some people in Pittsburgh, more angry than grief-stricken, dangled an effigy of Czolgosz from a factory crane. The knives they plunged into the body glinted in the electric light.2

The train arrived in Canton on Wednesday at noon, and the president’s body was carried into the courthouse for a final viewing. Local officials insisted that the casket be opened, and then regretted it. When a chandelier’s light was directed onto the president’s face, the shock was audible. It was, said one reporter, “pitifully unfortunate, as the discoloration had increased.” Witnesses emerged from the scene, sobbing. They had, perhaps, expected to see a man safely in repose, ready for eternity. Instead, they looked at the decay of death.

Ida McKinley wanted to see that face, too, to have a last good-bye, but no one was willing to open the coffin for her. She did persuade officials to let her husband’s body lie at home for a last night, and there she remained sequestered, unwilling or unable to attend the church funeral and the burial. When the president’s coffin was carried out of the house, an observer below thought he saw her. Someone pulled back a curtain on the second floor, and a frail, mothlike face appeared, looked down, then faded away.

At 4 p.m., the twenty-fifth president of the United States, followed by eleven flower-filled cars, was carried to Canton’s Westlawn Cemetery and placed in a family vault. As they had at each event in this long ritual, the Buffalo representatives stood in line with President Roosevelt and members of the cabinet as the casket moved past. For days, these men had been honored members of the funeral party. Roosevelt had gathered them together on the train and thanked them for “the bearing of the people of Buffalo after the terrible tragedy.” What they had offered and done, he said, “was appreciated more than words could make plain.”3

II

FAULT LINES

The funeral trip had been hard, but now the Buffalo men faced a new challenge: They had to go home. They had to pick up the pieces of a city in shock, steer the public away from its grim fixation with the president’s death, and rescue the Exposition.

They also had to deal with the city’s recent grandstanding: its pride, its sense of real importance when McKinley seemed to be recovering. They had to contend with the fact that some commentators blamed Buffalo for McKinley’s death. These critics said the police department hadn’t done enough to protect the president and suggested the city’s surgeons had been bumblers. The physicians had made a “startling error of diagnosis” and been overconfident. “What excuse must be offered to the public for the utter inability to find the bullet even in the dead body?” asked New York surgeon George Shrady in the Medical Record.

Others accused the Buffalo doctors of being unprofessional. They had been optimistic when they should have been circumspect and cautious, and they had stooped to undignified squabbling. They had disagreed over the path of the bullet, over the meaning of the president’s high pulse, over whether or not a poison had caused the gangrene. They had “talked too much.” A Manhattan doctor thought the finger-pointing could have waited at least until after the president’s body had made it to its resting place.

The surgeons fought back. There had been no disagreements, no unprofessional behavior. They condemned such “scandalmongering,” particularly from the New York yellow press. Another medical journal entered the fray and leapt to Buffalo’s defense. How could anyone insinuate that the tireless physicians of Buffalo had not done everything they could? They had, after all, kept the president alive for a week. These innuendos had “stung the whole medical fraternity” and turned McKinley’s death into a “popular spectacle.”4

Perhaps worse than the reproach, though, was the pity.

The New York Times reported that Buffalo was utterly shattered. Even before the Exposition, it noted, “there was no city in the country where friendship and devotion for [McKinley] were more marked.” And after it had poured its heart and soul into the Exposition, the city had then experienced ten days of worry and heartache. Now it had sunk even deeper, into depression “beyond expression.”

City officials and Exposition directors could not deny that the assassination hovered over the fair. The gates opened again on September 16, and more than sixty thousand visitors filed into the grounds. They went dutifully to cattle shows and watched Short Horns and Dutch Belted and Holsteins win money and silver cups. They stood by a wireless telegraphy demonstration and stayed for the fireworks at the Park Lake. And they applauded when applause was called for. But their enthusiasm seemed forced, as though they were trying to exorcise the sadness. Everybody knew—the newspapers were full of it—that Czolgosz was close by, still eating and sleeping well, and that maddened them.

Showmen felt the gloom too. A week after the president’s death, the Buffalo Commercial reported that performers at the Indian Congress had sensed bad spirits flickering through the fairgrounds. Chief Seven Rabbits, medicine man of the Congress, condemned the spirits and asked his followers to pray—for snow. He believed “that snow would be the only thing to drive bad spirits away in this climate.”

Buffalo was good at snow, to be sure, but in mid-September? Even Buffalo couldn’t answer that prayer. Meanwhile, Director-General Buchanan was receiving bundles of telegrams. People were wondering whether the Exposition was closed for good.

Determined not to bury the fair along with the president, John Milburn begged people not to give up on the show. He reminded the public that the Exposition was a tribute to McKinley and his policies. Others echoed him, suggesting that McKinley was martyred for the fair, that he had given his life supporting the show, and that the Pan-American was now a McKinley shrine.

In fact, a shrine of sorts was in the making. A group of Ohio visitors, surveying the assassination site in the Temple of Music, made a startling find. Almost in the very place where McKinley had been shot, in the grain of the wood floor, they found “a splendid likeness” of the dead leader. If visitors looked at the image in the right light (afternoon was best), they could see McKinley’s “high forehead and Napoleonic nose,” not to mention his “heavy overhanging eyebrows.” The face in the wood attracted scores of sightseers.5

On the Midway, the Animal King rallied to the cause. True, his lion-cage weddings had been derailed by the death of the president. Two of the fearless couples had not been able to reschedule and were married tamely in the Sunday School Room of the Central Presbyterian Church.

But Bostock announced more weddings, and added other shows. In a burst of optimism, he repainted the exterior of his exhibit hall in the colors of the rainbow. And he bought more animals: a new hyena; a Tasmanian devil; two polar bears; a red river hog from Egypt; a herd of trained zebras; and a troupe of baby elephants who could play on a seesaw, walk on their hind legs, and roll barrels. The showman also printed twenty-five thousand postcards picturing himself, Madame Morelli, and Captain Bonavita sitting with a perfect pyramid of twenty-seven lions. “The Climax of Animal Subjugation,” the caption read. A one-cent stamp sent the card across the country.

There was very little that ruffled the confidence of the Animal King—including, it seems, the man who paid for a ticket and entered his lion show on September 12. We do not know whether a report triggered the stranger’s visit, or whether it was just routine scrutiny, but the Humane Society agent took a seat in the crowd at “The Training of Young Lions,” one of the most popular wild-animal acts. He watched for a bit, eyeing the animals carefully. What he saw disturbed him. The trainer used a sharp iron prong to deliver discipline, and at least one young lion was bleeding. The agent brought formal charges of cruelty against the show. Bostock was called into court to testify, and, genial as ever, promised to promptly remove the act in question.6

III

THE VERDICT

On September 16, the American public, not to mention Buffalo residents, received some sense of justice done when the grand jury of the Erie County Court indicted Leon Czolgosz for murder in the first degree. Czolgosz appeared at the arraignment in a rumpled linen shirt and a new beard. His hair, no longer pomaded, looked lighter and more unkempt. He came into the courtroom, looked at the ground, and stood mute.

Thomas Penney, the district attorney, got down to business quickly.

“Czolgosz, have you got a lawyer?” he asked.

There was no response.

“Have you got a lawyer?” he asked again.

Silence.

“I say, Czolgosz, have you got a lawyer?”

Nothing.

He was impatient now. “Czolgosz, you have been indicted for murder in the first degree. Do you want counsel to defend you?”

Nothing.

Penney moved closer to the prisoner, almost face-to-face: “Czolgosz, look at me and answer.”

Still nothing.

One reporter who watched the procedure said that the prisoner stared emptily, as if he were “insane.” Others interpreted the vacant looks as subterfuge. He was pretending to be insane. Or perhaps he was acting out an anarchist script. Criminal anarchists had been known to keep silent until all hope of avoiding the death penalty was past, then jump up and shout their vile beliefs.

The ensuing murder trial brought the city of Buffalo high praise. By most accounts, it was a model of speed and efficiency and demonstrated America at its most civilized. If it had been performed as an exhibit at the Pan-American, John Milburn and company would have been delighted.

Beginning on September 23, the quickly chosen jury of twelve men considered a long parade of experts and witnesses for the prosecution. Judge Loran Lewis, on the other hand, told the jury that his assigned job as Czolgosz’s defense attorney was “exceedingly unpleasant.” He explained that there was no denying that the defendant had shot the president. The only question was whether or not he was sane. If he were sane, then he was guilty and must be punished. If he were not, then he would be acquitted and “confined in a lunatic asylum.” The problem, he went on, was that the defendant had, for the most part, refused to speak to his court-appointed lawyers.

Lewis did make a small attempt at an insanity defense. All people, he asserted, wanted to avoid death. And yet this man had done a deed that he knew was certain to cause his death. “Could a man with a sane mind perform such an act?” he asked. He suggested there might be benefits to finding the defendant insane. If McKinley had been shot by a madman, the nation would breathe a collective sigh of relief: It wouldn’t have to worry about “a conspiracy of evil disposed men” who might want to hunt down other rulers, even another president of the United States.

Lewis did not enlist the help of any witnesses to make his case; nor did he call on any one of the five psychiatric experts who had met with Czolgosz. Dr. Carlos MacDonald of New York City’s Bellevue Hospital might have helped the defense, admitting as he did that the psychiatric history of Czolgosz had been rushed, and that physicians had been unable to interview the accused man’s relatives.

Instead, the defense attorney, a veteran judge with the New York Supreme Court, directed the jury’s pity to the fallen president. “He was a tender and devoted husband,” he said, “a man of finest character and his death is the saddest blow I have ever known.” As he spoke, his voice shook, and he had trouble withholding his tears. Meanwhile, Czolgosz sat stonelike, his head tilted. Flies landed on his forehead and he made no effort to brush them away.

Prosecutors maintained that Czolgosz’s sanity was demonstrated by the fact that the defense could not prove—did not even try to prove—otherwise. They were thus spared the pain of discussing what had moved Czolgosz to anarchism. They did not have to listen to the assassin talk about the division of wealth in the country or about the condition of poor people. Ideas like these might have pointed to the man’s sanity, to be sure, but—this was the tricky part—they might have elicited an emotion that no one, defense or prosecution, wanted to see in the eyes of the jury, and that was sympathy.

It was over in a flash. The jury left to consider the evidence at 3:50 p.m. on September 24 and returned just over half an hour later to deliver the verdict: guilty of murder in the first degree. The sessions of the trial had lasted less than nine hours—including an hour and a half to select a jury. A few days later, Czolgosz was sentenced to die by the electric chair at the end of October. After hearing his sentence, the prisoner returned to jail, and, as usual, ate a hearty meal. He then went to bed and slept soundly.7

The proceedings of the trial used up nearly every word of admiration in the lexicon. Only a few commentators, including Emma Goldman and some psychiatrists, described it as farcical.

IV

THE EXCISION

While Buffalonians were pleased with the murder verdict, many local African Americans read the trial transcript with suspicion. The prosecution had called many witnesses to the stand, including soldiers, Secret Service men, and city police. The lawyers had not, however, been interested in hearing from Jim Parker. Sometime between the shooting in the Temple of Music and the indictment and trial, Parker had been erased from the assassination’s record of events. Secret Service agent George Foster, involved in the takedown of Czolgosz, when asked specifically about Parker, testified that he “never saw no colored man in the whole fracas.”

The act of ignoring Parker did not go unnoticed. Across the country, some newspapers picked up on the slight and quickly said, “We told you so.” At the same time, white Republican papers rose to defend Parker, rallying evidence. If he hadn’t actually intervened, why had every paper labeled him a hero right after the event? Why had Agent James Ireland, in his report to the chief of the Secret Service, named Parker as a man who had grabbed the assassin? Why had Parker originally been named as one of the victims of Czolgosz’s assault? Other witnesses testified to his presence at the Temple of Music, including two white southerners who had been at the fair.

On the night of September 27, a number of Buffalo’s African Americans met at the Vine Street African Methodist Episcopal Church to weigh the conflicting reports. While a committee convened in a separate room, men rose to speak. One, named Shaw, had worked with Parker at the Plaza Restaurant and argued that the effort to “discredit” Parker was the result of a plot. “Should we fail to emphatically resent it,” he contended, “I claim we are a disgrace to our race.”

As Shaw was speaking, Parker himself arrived at the door of the church, entered, and moved down the aisle. The audience swooned. Women fluttered handkerchiefs and men whooped, tossed their hats, and boomed three cheers.

The committee reentered the room, discussed the evidence, and read out two resolutions. One lamented McKinley’s assassination. The other, directed at Parker, equivocated: “It is the sense of the colored citizens of Buffalo, N.Y., in mass meeting assembled, that they very much regret the clash of statement in respect to the reported act of heroism on the part of James B. Parker.” The committee members regretted it so much, apparently, that they could not offer an opinion, and definitive word would have to wait. It would be up to historians, they said, “to award honor to whom honor is due.”

But while the committee held back, others who were there did not. In giving three cheers for Parker, in urging him to speak to them, and by surrounding him on the street after he left the church, they told him they believed him.

Soon afterward, Parker did what he could on his own to set the record straight. He went beyond Buffalo, lecturing about the assassination throughout the East, and he visited President Roosevelt at the White House. While in Washington, he explained to a gathering at the Metropolitan AME church how he had come to the defense of the president. He told them how District Attorney Thomas Penney, for the prosecution, had interviewed him early on but then, somehow, had lost interest in his opinion. “I don’t say that this was done with any intent to defraud me,” he explained to the group, “but it looks mighty funny, that’s all. Because I was a waiter, Mr. Penney thought I had no sense. I don’t know why I wasn’t summoned to the trial.” A woman in the audience had a ready answer for him. “Cause you’se black; that’s de reason,” she said.8

V

GERONIMO

Back in Rainbow City, temperatures were dropping, and on the Midway, performers found themselves unready for the cold. In Darkest Africa, the frigid weather forced villagers into borrowed clothes, and visitors found the sight ridiculous. The Africans also tried to warm themselves around a gas stove, and when one used a match and caused an explosion, singeing himself, it was another occasion for laughs. At the Old Plantation, the cold meant more entertainment, as “the darkies dance and sing with added vim.”

From the Indian Congress, Geronimo wasn’t amused, and he made a plea for seven hundred overcoats. At the Filipino Village, the cold weather aggravated the tuberculosis of a young woman, and she died.9

While occasionally turning their backs on performers’ needs, concession managers continued to use them to make money. And nothing made money more spectacularly than the show planned for the end of September by the Indian Congress. On September 26 and 28, up to twenty thousand guests took their seats to watch an Indian dog feast.

Frederick Cummins, manager of the Indian Congress, orchestrated the killing and eating of the dogs, but most people credited Geronimo with the inspiration. Throughout the summer and early fall, the Apache leader had become the most visible Native performer at the fair. Once known by the US Army as the “human tiger,” the warrior chief, like many other non-European men on the Midway, was now pictured as entirely tamed, even feminine. He was said to be vain about his appearance, fussy about his hair, and expert at bead designs. Word had it that he had taken up a musical instrument and had begun offering cooking classes.

Apache leader Geronimo and Wenona, the “Sioux” sharpshooter, center, pose with visitors and other members of the Indian Congress.

Geronimo seemed so removed from his former life as an enemy warrior that he not only played an Indian in sham battles; he also offered white guests a chance to play Indian. Without taking off their top hats or changing out of their shirtwaists, and with enough money—usually seventy dollars—visitors could be inducted into a tribe, usually Apache, Oglala Sioux or Arapaho. They received funny, pretend-Indian names. Railroad executive Charles Clark of the Big Four Railroad became “Chief Likes His Eggs”; Captain Hobson of the Queen & Crescent Railway became “Chief Blows Them Up.”

Geronimo had performed agreeably in all of these ceremonies—he was, after all, still a prisoner of war—but, especially as the season wound down, his irritation at curious crowds seemed to grow. He began to charge more and more money for photographs, and, one day in September, he lost patience altogether. When a spectator tried to follow him for a photograph, Geronimo “buckled into him, tipped him over, [and] knocked his camera to one side.”

Geronimo wasn’t alone. Other Plains Natives may not have acted out in anger, but they turned jokes on their audiences. The Indian Congress regularly featured a line of performers giving “speeches” in Native languages. These speeches tended to be a commentary on visitors, criticizing their clothing, their appearance, and their mannerisms. Behind them, other Native men listened and laughed.

Now, Geronimo and seven hundred other Native people had something different to offer Exposition crowds. Perhaps they were unapologetically or defiantly performing a meaningful ritual. Or perhaps they were performing a “savage” act to bring in revenue. Likely they were doing both.10

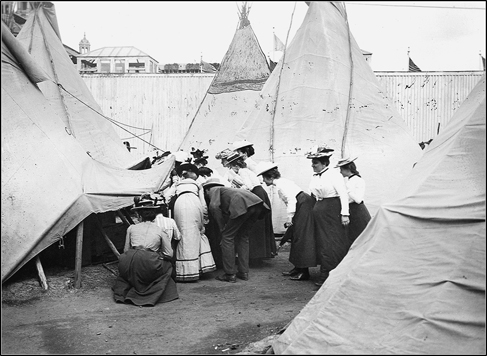

At the Indian Congress, fairgoers peer under the flap of a tepee.

Dog feasts were nothing new for some Native peoples. Northern groups especially, like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and the Bannock of Idaho, held dog feasts on special occasions, as did a few southern tribes like the Osage, and the Sac and Fox. Occasionally, tribes fattened their own animals for the sacrifice, while others collected stray dogs from beyond their encampment. Women often did not partake.

Not surprisingly, members of the white press had weighed in on these events with disgusted sighs. What had the missionaries, the teachers, the churches accomplished if these people were still eating “pets”? At the same time, dog feasts reinforced reporters’ own sophistication. And, they had to admit, they were fascinated.

The Buffalo dogs were taken quietly at first. Managers of the Indian Congress bought strays from dog pounds and dogcatchers, and they emptied neighborhoods, streets, and parks. By September 22, three hundred dogs, including poodles, terriers, and spaniels, had been corralled. The Congress, though, wanted four hundred more.

In Buffalo and nearby towns, city residents, eager for the money or the attention, offered up their own animals. In Tonawanda, a woman named Johnson offered her five adult dogs and seven pups. She needed the two dollars. And a Mrs. Foster of Elmira sent a telegram to Henry P. Burgard, president of the Indian Congress, stating that she had a pug named Lillian Langtry that she would part with “if she was certain an Indian would eat it.”

Newspaper accounts like these prompted Buffalo’s reform-minded residents to protest. In fact, the Humane Society would see its failure to stop the dog feast as one of the year’s great disappointments. When officers of the society called on the management of the Indian Congress to halt the event, they were shown permission records issued by the United States Government. There was nothing the society could do.

The animal protectors also admitted they were conflicted. Humane Society officer Matilda Karnes explained that respecting Indian visitors meant acknowledging that the “religious festival must be considered legitimate.” It was the “degradation which was forced upon us,” she said, that was humiliating. The society had labored long to exert a positive influence over young people and this “barbarous” event was destroying its good work. The group knew the counterargument: Killing dogs was not a lot different from slaughtering other animals for food. But, Karnes said, that was not the point. What the society condemned was not the killing, but the spectacle of killing.

At 5 p.m. on September 26, before an audience of at least ten thousand, the sacrifice began. Geronimo killed a dog with a bow and arrow, and then sharpshooter Wenona took her turn with a rifle. Newspapers carried every detail, from the killing of the animals to the eating of them. They reported that Geronimo ate two dogs. They tasted, he said, “like fried frog legs.”11

Frank Bostock did not comment publicly on the commercial success of the dog feast, but he was just yards away from the event. He made his living showing off his mastery of animals. Was there money to be made in the death of one?

Not unrelated to that question was the ongoing arrival of animals at his compound: a new llama, a vicuña, a razorback hog, and a black snake, sixteen feet long. There never seemed to be an issue with overcrowding in the arena. And when it came time to sell animal skins at the end of the Exposition, Bostock had plenty to offer.

Bostock’s Doll Lady, meanwhile, worked through the fall without complaint. Tony, on the other hand, had grown tired of their secretive routine. One night, he crawled through the window of Chiquita’s dressing room and steeled his nerve. He told her he loved her, and asked how she felt about him. Alice told him she loved him, too. “Do you love me well enough to marry me?” asked Tony. She said she did.

Tony wanted to get married then and there, but Chiquita stopped him. She was afraid of Bostock. She was, however, willing to make a date to elope: Friday night, November first. It was the night before the Exposition closed, so it seemed safe enough. Tony enlisted his brother Eddie to help with the engagement by purchasing a ring, and shortly afterward he hoisted himself over the roof of the Ostrich Farm and sneaked into his sweetheart’s quarters to present it.12

VI

THE DARK MARK

On September 25, a Buffalo newsman estimated that of the fifty-eight thousand at the fair the day before, less than two per cent were local visitors. He accused city residents of forsaking their fair, noting that while the rest of the country was being asked to go to the Exposition out of patriotic duty, city residents had been let off the hook. It was time they did their part. “If Buffalo people turned out as generously as Chicago people did at the World’s Fair at this time of the season, the attendance would be nearer to 100,000.”

Residents rallied. September 28, Railroad Day, which had been postponed when McKinley died, brought in nearly 120,000 people. Mabel Barnes showed up, of course. Back at school now, and forced to squeeze her visits into weekends, she had been to the fair only twice since McKinley’s death. Now, arriving alone, she was on a mission to see every last bit of the Exposition. She had state and country buildings on her list, art and sculpture to see, and she wanted more music, more parades, more Midway. Years later, when Rainbow City had been reduced to splinters and dust, and Mabel sat assembling all her notes, perhaps she took pride in the fact that she, above all others, had been flawlessly dedicated.13

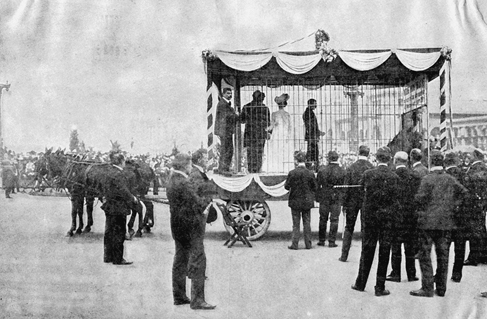

While the loyal schoolteacher made her way speedily through exhibit buildings on Railroad Day, other visitors watched a man named Leo Stevens, “the human bomb,” ascend into the sky in a big round ball, explode out of it, and parachute back to the ground. A good many of them also took the opportunity—finally—to witness a young couple marry in the company of lions.

At 4:45 in the afternoon, the betrothed couple, Caro Clancy and William McAlpin, waited while Bostock’s lion trainers marched over the Triumphal Bridge, followed by the altar. The cage stopped in the middle of the Esplanade.

Miss Clancy, who wore a white gown, a feathered hat, and carried orange blossoms, and whose cheeks betrayed a tinge of excitement, climbed into the cage and stood between her future husband and the lions. The minister positioned himself just inside the door and began to read the service. The trainer waved his whip up and down. With great efficiency, the minister led a prayer and produced a certificate. Then he edged to the door. The lions roared. “Hurry up, hurry up,” a witness shouted. The groom and the minister moved out of the cage first, and the bride followed them. “She was,” said an observer, “first in and last out.”14

The long-awaited lion wedding.

It is hard to know whether never-ending comparisons with Chicago’s world’s fair bothered or pleased Buffalonians. What is certain, however, is that October 7, Illinois Day, generated more than the usual fuss. Illinois governor Richard Yates, Senators William Mason and James Templeton, the mayor of Chicago, and Chicago aldermen would be honored with parades, a military review, banquets, luncheons, and a tour of Niagara Falls. The supporters of Rainbow City would show the former denizens of the White City how proud they were of their own production.

The festivities got off to a shaky start. For unclear reasons, the Illinois regiment serving as the governor’s escort traveled from Chicago to Buffalo on October fifth with almost nothing to eat, so the soldiers arrived hungry at Buffalo’s Exchange Street Station. A two-mile march to the center of the city and a train ride to the Exposition, again without food, did nothing for their frames of mind. Aboard the train, they sang loud songs about chicken, beef, and hot dogs. “Hallelujah give us a sandwich to revive us again,” they crooned. They also pretended to be conductors. “The next station at which this train stops is Dinner Avenue,” shouted one soldier. Another claimed, at the Auditorium stop, that he could eat the building’s bricks. Thirty hours after leaving Chicago, they arrived at the grounds and made a beeline for Bailey’s kitchen.

The mayor of Chicago couldn’t attend the event. But city aldermen made their way east in large numbers, and Governor Yates arrived in Buffalo early on Sunday, October 6. After attending church, the governor’s party of twenty-seven decided to tour the Niagara River along the Canadian side. They were on their way back by rail, heading toward the falls, when, a little after 4 p.m., their car lurched, smoked, and stopped dead. There were, someone recalled, “a few screams.”

The governor and his fellow passengers, all uninjured, held a conference and decided, with no help imminent and no way to call for help, that the solution was to get out onto the tracks and walk the rest of the way to the falls. Two to three miles, they were told. The young, athletic governor was especially undaunted. He had, as a college student, walked seven miles before breakfast, so this was nothing.

But it wasn’t a couple of miles. It was six. As the group trudged along the rails, the sun went down, and then set. The men and women had nothing to eat. The roadbed, which skirted cliffs and moved through narrow trestles, was rough. The party straggled into Niagara Falls, took a working railroad car to Buffalo, and, around 8 p.m., went straight to their hotel.

There was more awkward walking the following day, because fair officials forgot to tell the Illinois visitors how long it might take to get from their hotel to the Exposition. But good humor prevailed, and the ceremonies in the Temple of Music moved forward without mishap. The visiting speakers thanked Buffalo, congratulated the city on its Exposition, and only discreetly alluded to the Columbian Exposition.

But they might as well have waved a White City banner alongside their regimental colors, for the theme that rose above all others was Buffalo’s—it seemed to belong to Buffalo—sad assassination. Senator Mason, after talking about the virtues and beauty of Illinois, offered condolences. Americans knew that Buffalo had been kind and attentive to the president, he said. They also remembered “that the blow at the nation was struck at Buffalo.”

Governor Yates graciously offered thanks to his audience and explained that Illinoisans knew how they felt. Lincoln, America’s greatest hero, and an Illinois native son, had fallen to a madman’s bullet. They felt for Buffalo. Edwin Munger, chairman of the citizens’ committee of Chicago, added that his group had come to Rainbow City “with saddened hearts and drooping spirits.” Now here they stood, he said, “in the almost visible presence of the most awful and most senseless crime of the century.”15

For all of Rainbow City’s artful colors and lights, its grand exhibit halls, its celebration of the Western Hemisphere, and its Midway, what stood above them for these Chicagoans was Buffalo’s tragedy.