I

BRAIN FEVER

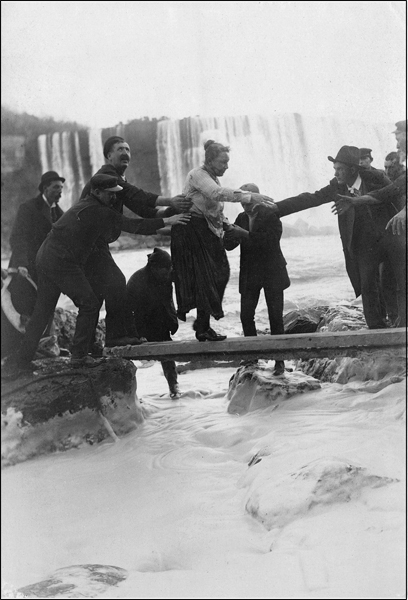

Annie Taylor was still alive—that much was certain. Soon enough, though, it became apparent that she was stuck in the barrel. Waterlogged, cold, and weak, she couldn’t edge herself out, and nobody else could either. The thick oak that had shielded her from the blows of a thousand rocks now encased her like a form-fitting coffin. It was unclear how long she could last, or what shape she was in.

The men sent for a saw. With that in hand, they cut their way through the oak, took off the top of the cask, and, with a mighty tug, pulled her out. She had a bleeding laceration behind her ear and she looked shipwrecked. But, with help, she stood up and spoke.

“Have I gone over the falls?”

Annie Taylor’s mind was muddled, but her limbs were intact. She walked upright along the rocks and climbed across a plank to a boat. Photographers captured the moment—her hair in a bedraggled topknot, her dress disheveled, her hand outstretched for help. Within an hour, she was back at her boardinghouse, sipping coffee and brandy and thawing out with the help of a stack of blankets, hot-water bottles, and a coal fire.

When she felt well enough, she spoke about what she remembered. As she plunged through the rapids, she said, she thought she was suffocating. But worse, she recalled, was the noise that came rumbling through the barrel’s thick walls. It was the deadly roar of the falls, and it grew to a thunder.

She felt a short drop. Rocks, she imagined. Still the rapids.

Annie Taylor, dazed and triumphant.

Then came the “terrible nightmare.” She couldn’t say whether the barrel had stalled, or risen up, or lurched. But all at once she felt hollow, and her stomach flew into her throat. “Something,” she said, “had given out from under me.”

The next thing she knew was that she hit a rock, slamming into it so hard that her barrel broke and cold water struck her face. Later, of course, she realized that it wasn’t a rock at all, just the impact, 158 feet down. Her barrel hadn’t broken, either, just leaked. The water, she remembered, felt “so cold.”

She thanked people, like Captain Billy Johnson, who had urged her to install arm straps. He had helped her avoid “having my brains beaten out.” And she thanked God. “I owe a debt of great gratitude to Him,” she declared.

Asked whether she would ever do it again, she had a quick reply: “I’d sooner be shot by a cannon or lose a million dollars than do it again. I will never do it again. But I am not sorry I did it, if it will help me financially.”

Tussie Russell was already at work on that score. Annie Taylor was receiving offers of marriage, paid interviews, and appearances. Most urgently, there were offers from the Pan-American Exposition, and he was trying to hold out for a lot of money. He also had his hands full with the barrel itself. Even before the night was over, souvenir hunters had broken up the hatch, cut the harness to pieces, and hustled them away. Maybe they wanted a part of history, but, more likely, they hoped to sell it.

There was one hitch in the plans, however. Annie’s stunt began to catch up with her. Bruises had begun to mottle her body, and she felt shaky—even “hysterical.” The next day, when she still felt unwell, a doctor did an examination. He saw the signs of a frightening illness—brain fever.1

II

THE BLIND SPOT

While Taylor lay sick and Russell fretted, another press agent, on a different account, stepped up his sales pitch. In the third week of October, Captain Jack Maitland released a storm of stories. Time was running out, he said, to go to one of the most remarkable performances in the whole United States. No one should miss Jack Bonavita’s twenty-seven lions, or Madame Morelli’s jaguars, or the “funny clown elephants.” There was a new show, too, just for “windup week.” Madame Hindoo was in town, with her serpent charmer Princess Brandea and their deadly cobras.

The publicist also let it be known that Frank Bostock was being honored. “New laurels have been added to Frank C. Bostock’s reputation,” Maitland asserted. The agent did not specify what laurels had been awarded or by whom. And he ignored the fact that in an end-of-the-fair contest for Mayor of the Midway, four concession heads had been nominated: Frederick Cummins of the Indian Congress, Frederick Thompson of “A Trip to the Moon,” Gaston Akoun of “The Streets of Cairo,” and Fritz Mueller of “Pabst in the Midway.” Bostock, despite his spectacular profile—or perhaps because of it—was not in the running.

Captain Maitland also made a final push for the Doll Lady. Chiquita, he announced, had been a stupendous success, and the parlors of the Exposition mascot had been thronged with visitors. No one should pass up the chance to meet the refined little person who had mingled in the highest society. Taking the public into his confidence, Maitland even whispered a little secret about the human sensation. Chiquita, he disclosed, needed a lot of sleep. “She rests ten hours at a stretch.”

Alice Cenda probably disliked having her personal habits shared with the public, but this might have been an exception. In just a few days, she would use this information as a cover. She and Tony, in their fleeting meetings, through go-betweens and in notes, had worked out a plan. On the second-to-last night of the fair, she would pretend to go to bed. Hours later, after her attendant and Bostock himself had retired, Tony would help her break out of her prison.

They thought they had worked out a good escape route. The Animal King bolted Chiquita in her rooms every night, and he had done a good job of securing her windows and doors. But he had missed something. Below Chiquita’s ticket window, customers had left a depression in the ground. This depression, if deepened, could provide an opening.

The performer bided her time. She did her best to please her manager, and, just as she had for months, she carried out her act seamlessly. She showed off her languages, signed autographs with her small, round script, and greeted hundreds of curious visitors. Back in the summer, she had had to cancel her show because shaking hands had hurt her. Now she allowed visitors to squeeze her small palm, minute after minute, all day long, without complaint.2

III

RICH PEOPLE, POOR PEOPLE

The last days of October at the Pan-American Exposition, just before the grand finale, hummed with purpose. It was a time for dismantling and packing and making unashamed efforts to squeeze the last pennies from fairgoers. Salesmen marketed everything from portable souvenirs to big buildings and their contents. It was a time of giving gifts for jobs well done. Concessionaires handed their director, Frederick Taylor, a gold-headed cane; garden workers gave their chief a silver punch bowl; and the electrical engineers presented their head with an inscribed gold watch. Not to be outdone, the Exposition Hospital staff honored their superintendent, Adele Walters, with a silver-topped umbrella and gave the long-suffering Exposition physicians new instrument cases.

It was a time, too, for hearsay. Stories coursed through Buffalo and the fairgrounds. Everybody agreed that the Exposition cost a lot more than expected and attendance was a lot less than they wanted, but what did this mean? Who would be out of luck? Who might not be paid? And, above all, could the fair do better? Seven and a half million tickets had been sold so far. Was there hope for more?

Buffalo businesses were urged to let their employees have one last look at Rainbow City, and bring up its numbers. Any day in the next six days would do, promoters said, just—please—boost the attendance at the “greatest enterprise ever planned and carried out by Buffalo.” If nothing else, they said, go on Farewell Day, Saturday, November second. And, as though they couldn’t help it, they pulled out their timeworn tactic: Shame people with the White City. “It should be the aim of everyone to swell the Farewell Day crowd, to make it reach the 200,000 mark,” wrote the Buffalo Commercial. “At Chicago a daily attendance of 300,000 was not uncommon toward the last of the exposition season.”3

Pan-American directors advertised energetically these last days, but they didn’t want just any visitors; they wanted paying customers. It was brought to their attention, however, that some people in western New York hadn’t been able to afford the Exposition. The parents of some local schoolchildren had found it a challenge to scrape together the round-trip streetcar fare of six cents, much less the discounted admission ticket of fifteen cents.

Learning of this, Buffalo philanthropists rose to the occasion and bought trolley and admission tickets for six thousand children. Impoverished adults were a different matter. A rooming-house owner sent an appeal to the press, explaining that three of her lodgers had never been inside the fairgrounds, though “how much they would like to go” she couldn’t begin to say. And why had they missed out? “For the simple reason that they cannot afford it.” One, she said, was a woman and her young daughter, who both worked hard. The mother washed and cleaned houses, and some days she could hardly crawl home. But “they do not have one penny to spend—hardly enough to buy clothing.” Another was a woman with a baby whose husband had left her, and the third was just dirt poor. “Why not,” she pleaded, “let the poor people of Buffalo . . . see a sight of their lifetime?” Why not let them have “one day of recreation in which to forget their poverty?”

The answer, not surprisingly, was no. For an exposition company that could not at that moment pay its contractors and builders—not to mention mortgage holders—generosity, or justice, was out of the question.

To paying visitors, Pan-American promoters offered an unforgettable final day. First of all, fairgoers would be able to leave a legacy. They could drop their names and addresses into boxes on the grounds, and a record of their attendance would be stored in the fireproof archives of the Buffalo Historical Society, where it would be kept for “all time.” (It wasn’t.)

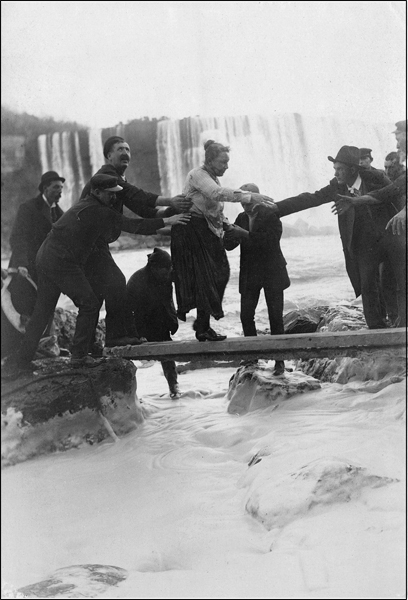

In addition, the fair’s famous Indian warriors would kill Custer once and for all, and then attack a wagon train. The United States Cavalry would then avenge Custer. Indian women would be making food, the men would be resting, and suddenly the soldiers would strike. It wouldn’t be the usual “harmless” battle, either. The 150 Indian fighters, being real soldiers, and 300 Indians, being real Indians, meant that the “shooting and dying and scalping will be done in truly a realistic way.”

This fight, one newspaper said, would sum up the story of the fair. “Pitted against each other,” the Commercial explained, “will be the representatives of the forces that have met in deadly conflict for over two centuries in the New World—one protecting the advance of civilization, the other virtually courting extermination in its efforts to retain a continent for primitive savagery.” Since the nineteenth century had seen the triumph of civilization, and the Pan-American Exposition had celebrated that triumph, it was only fitting that at the end of the fair these two groups should engage in final, “friendly” conflict.

The popular sham battle between the Indian Congress and United States soldiers, in the Exposition stadium.

If this reporter had paid some attention to the news items his colleagues had produced over the Exposition season, he would have realized his summary left a few gaps. True, the local press had devoted countless inches to describing the backwardness of the Exposition’s indigenous peoples. But, intentionally or not, it had added nuance to the picture. It had described how Geronimo, for instance, had been a tireless entrepreneur, promoting the sale of crafts and negotiating contracts. It had recounted the ways he had defied Exposition visitors and unapologetically endorsed the dog feasts. It had depicted other Native performers laughing at white audiences, turning the tables publicly and secretly, in ways modern and not modern, embracing “progressive” and “primitive” both. And it had revealed the ways that the Native performers had established dynamic Exposition communities. The fair served as a great intertribal powwow, with dances and feasts that cemented alliances and showcased resilience.

The Indian Congress show would lead off the events on Farewell Day, but there would be other big acts. “Brawny” Irishmen would oppose each other in a hurling match, and on the Midway, cakewalkers, pie-eaters, and spielers would vie for prizes. The committee for Farewell Day would bring in special celebrities, too. Carrie Nation would draw crowds with her inflammatory temperance talk, and word had it that barrel rider Annie Edson Taylor had (mostly) recovered from her descent over Niagara Falls, and would be willing—perhaps even eager—to receive visitors at the Exposition.4

IV

DEADLY FORCE

As they had done for most of the fall, fair directors and city leaders stirred up excitement for the Exposition even as they beat back memories of September. They had even, begrudgingly, worked assassination scenes into tourist itineraries. The Temple of Music, the Exposition Hospital, the Roosevelt inauguration site, and the Milburn house had become must-see locations.

On October 29, though, the painful drama of early autumn once again took over the news. It was the day designated for Leon Czolgosz’s electrocution at the state prison in Auburn—four days ahead of the fair’s grand finale. The papers were full of the event, and no matter what dazzling shows had been conjured up for the close of the fair, this story was impossible to ignore.

Among the men invited to witness the electrocution was Charles R. Skinner, who had served in Congress with William McKinley and was now an official with the New York legislature. He was pleased to be at Auburn. He had been unable to attend the execution of Charles Guiteau—President Garfield’s assassin—because of a daughter’s illness, and he did not want to miss this one. He arrived in Auburn the night of the October 28, visited with friends, and ordered a wake-up call for six in the morning.

Inside the prison, meanwhile, two physicians made a final examination of Czolgosz, and again convinced themselves of his sanity. They were so impressed by his mental faculties, in fact, that one asserted that he seemed “exceptionally intelligent for one in his walk of life.”

The next day, a Tuesday, was cloudy. The weather was just right, Skinner felt, for what was to come. In the early morning, he presented his “invitation” to the prison warden and gathered with thirteen other witnesses in the warden’s office. They were led down a corridor to the death chamber.

Except for witness chairs and the prisoner’s oak seat, the room was bare. There were windows, but they were too high to allow anyone to look in or to offer the condemned a glance outside. At the back of one wall stood a small enclosed area—the “executioner’s box.” Inside, modern technology was manifest: electric lights, electric wires, an electric bell to inform the occupant when to pull the switch. The switch itself was brass, with an insulated handle. The man who closed the electrical circuit could not see the prisoner. Nor could the prisoner see him.

It was just after seven o’clock when the witnesses heard shuffling in the corridor and a lock clicking open. They saw Czolgosz, between guards, enter the room and walk to the chair. He was expressionless. Guards tied the restraining straps around him and attached the headgear.

The prisoner was then permitted to speak.

“I killed the president because he was the enemy of the good people, the good working people,” he said. “I am not sorry for my crime. I am sorry I could not see my father.”

Inside the box, out of sight, the electrician—a man named Davis—waited for a signal from the warden. He got it. Then, for just over a minute, and at intervals, he delivered varying voltages—seventeen hundred being the maximum—into the body of Czolgosz. Davis was satisfied with the result. “It was,” he said, “as successful an execution as I have ever operated at in all my experience.” Other attendees concurred. There was “no scene,” one commented. “Everyone conducted himself with remarkable sang-froid.”

Like the others, Skinner watched the extinguishing of life with little emotion. There was no more terror in the scene, he asserted, “than to see a cat catch a rat.” The prisoner’s face had been obscured by a black cap, and Skinner and his fellow witnesses had simply focused their minds on Czolgosz’s despicable act. “We all thought of the great crime against our country,” he said, “and nothing of the poor form in the chair.”

Dr. Carlos MacDonald, an attending psychiatrist, was not as indifferent. He took pains to note that Czolgosz’s body was “thrown into a state of extreme rigidity,” as soon as the circuit closed, and that every muscle had gone into a “tonic spasm.” Another witness, a sheriff, noted that after the first shock, when physicians felt at the jugular vein for a heartbeat, they asked for a second round of electricity.

Physicians performed the autopsy almost immediately. To their relief, Czolgosz’s brain seemed perfectly normal. Examining it in full, they could see nothing that spoke of pathology. They thus concurred with official psychiatrists and prosecuting attorneys that the assassin had been sane.

Later that day, what remained of Leon Czolgosz was placed in a plain black casket, doused with sulfuric acid and quicklime to encourage disintegration, and buried. Czolgosz’s brother, Waldeck, who had traveled to the prison from Ohio, paid a visit to the grave. Speaking to the press, he said that he had no plans to change his name or to go into hiding.5

And so it happened that, in the fall of 1901, the Pan-American Exposition, whose designers had worked so hard to demonstrate all the beautiful things electricity could do, became suddenly linked with the way electricity could kill. For months, Rainbow City had dazzled the public with art and sculpture that celebrated the hydroelectric power of Niagara Falls. It had captivated visitors with the magic of transformers. Its magnificent rheostat, mirroring the coming of dawn and dusk, had taken the spectacular lights of Chicago’s White City and moved them, quite literally, a step ahead. Its electric streetcars had taken visitors to and from the fair and its streetlights had illuminated walkways. Its electric elevators had ascended the fair’s highest tower, named in honor of this wondrous technology. The Queen City, some declared, should be known from then on as Electric City. Now, though, the public was reminded that electrical current could inspire fear as well as awe.

Rainbow City’s founders and fairgoers had not, of course, been unaware of electricity’s dangers. Stories of fatal accidents near power stations and power lines appeared in the news with regularity. In New York State, in two recent years alone, ninety people had died by electric shock. By 1901, American consumers were so apprehensive about using electrical appliances that many of them shied away from newly patented toasters and irons. And at the Pan-American fair, electricity was blamed for a peculiar malady. In October, the Buffalo Express printed a column about a newly discovered ailment, the “Exposition Collapse.” Its symptoms were “exhaustive nervousness” and, in the worst cases, “nervous prostration.” Apparently, said a consulting physician, people believed that the “continuous use of such tremendous quantities of electricity, creating such a powerful light night after night for six months had resulted in diminishing certain properties in the atmosphere, whose presence was beneficial to the nervous system.” The physician readily dismissed the association, arguing that nervous prostration in Buffalo was more likely due to the “steady strain of receiving guests and sightseeing and rushing around.”

The public was also mindful of the dangers of electricity, thanks to the high-profile rivalry between Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse and their support for alternating current on the one hand, and Thomas Edison and his low-voltage direct current on the other. In the early 1890s, Edison threw money and celebrity into persuading the public that alternating current was hazardous, and he demonstrated its deadliness by using it to kill animals, mostly dogs. He could do little, however, to explain away the fact that alternating current could travel long distances, and was less costly.

Buffalonians had certainly read about the “current wars.” If they knew anything about recent history, they were also aware that their city had a unique relationship with electrocution. One of the inventors of the electric chair was a Buffalo dentist named Alfred Southwick. In the late 1880s, he launched a campaign for more “humane” capital punishment. Representing the bluntly named New York State Death Commission, Southwick wrote in 1887 to Thomas Edison, asking for advice on electrocuting the condemned. The commission wanted an alternative to hanging—something more “civilized.”

Edison replied, saying that he couldn’t help. After a few months’ consideration, however, he wrote back, saying he had just the thing: one of George Westinghouse’s machines. “The most suitable apparatus for the purpose,” he advised, “is that class of dynamo-electric machine which employs intermittent currents. The most effective of those are known as ‘alternating machines,’ manufactured principally in this country by Mr. Geo. Westinghouse.” When the current from these machines entered the human body, Edison explained, the result was “instantaneous death.”

The commission was impressed and urged the New York State legislature to move forward. They did, setting 1889 as the date by which capital punishment would make the transition. Edison’s men did not hide their hope that AC would become known as “the executioner’s current,” and that condemned men would be “Westinghoused” in the same way that they had been guillotined (after French physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin).

Westinghouse, outraged, tried to hire an attorney to challenge the constitutionality of “electricide.” When William Kemmler, a vegetable peddler from Buffalo, became the first person condemned to die in the electric chair, Westinghouse paid to help Kemmler appeal his death sentence. The appeal failed. To make matters worse, the protracted electrocution of Kemmler in 1890 in Auburn was nothing short of a disaster. The prisoner shouted in pain, bled, gasped; his skin and hair burned; and his coat caught on fire. He had, said some, been “roasted to death.”

Eleven years had passed since Kemmler’s death. Alternating current not only had become standard for executions but also was used by industry nationwide. Edison’s campaign had backfired. George Westinghouse had been awarded the contract to light Chicago’s White City, and, at that fair, as well as in Buffalo, the technology linked utility with spectacle and awe.

Events in the fall of 1901 brought the perversities of electricity to center stage, but not everyone was disgusted by them. If for some people electricity linked distressing images of beauty and death, for others the association was strangely compelling. In this era of science and reason, individuals were sometimes drawn to mysterious forces—they went to Niagara Falls, after all—to see how close they could come to fatality. The electric chair held this same sort of dark appeal. It helped explain why more than a thousand people applied to see Czolgosz’s death. And it helped explain why, shortly after that electrocution, hundreds of people filed into Rainbow City to see the Animal King attach electrodes to the ears of an elephant.6

V

THE WEEPING WILLOWS

On Friday, November first, the day before the grand farewell, the Exposition opened without fanfare. Workmen hauled packed crates to railroad cars and concession owners tried to pretend the fair wasn’t in the throes of ending. Exposition buildings and Midway acts opened and closed on schedule, and demonstrations and drills went forward. On the Grand Court at night, fountains sent up plumes of colored mist; on the edges of buildings, the luminous jewels of incandescent lights waxed and waned.

Alice Cenda wanted nothing more than an ordinary day, where hours passed without incident, and people, particularly the Bostock people, took little interest in her work. She got it. She dutifully performed as the Doll Lady in her salon, greeted and dismissed her audiences, ate her supper, and in the early evening settled into her apartment. A Bostock caretaker fastened her doors.

Several hours later, at 11:30 p.m., a carriage with three men pulled up on Elmwood Avenue behind the fence on the backside of her concession. Tony got out and entered the grounds at the West Amherst gate. He moved from shadow to shadow and threaded his way behind the Exposition Hospital and the scenic railway. Mingling with late-night cleaners and sweepers and passing by weary performers, he approached Chiquita’s ticket booth. It was dark, but he was able to look through the window of the booth down to the floor.

“There she was,” he recalled. Maneuvering her through the opening—no bigger than a cat door—wasn’t as easy as they had hoped, however, and knowing that Bostock’s men were on the prowl, they worked fast. Tony pulled and Alice struggled, and she wriggled out. Tony carried her to the fence and signaled to his friends. The two men—fellow workers in the Indian Congress—were there, waiting. “I boosted her over,” Tony said, “and they caught her.” The only casualty was Alice’s dress, which snagged on the top of the barbed-wire fence. Once Tony made it over, the carriage pulled away.

Judge Thomas H. Rochford had probably seen a lot of hasty marriages in his time, and had helped tie the knot for dozens of seemingly mismatched people, but this might have topped them all. He had gone to bed when the knock came at his door. He could see a carriage outside, waiting, and he invited the couple inside. Tony said he was of legal age and Rochford knew Chiquita—he had been to the fair with his family. Tony didn’t have money, but he promised to pay the judge later, and Rochford was willing to help. He interviewed the couple, signed a marriage certificate, and watched them drive away.

Maybe it was the commotion of escape that alerted the Animal King to Chiquita’s disappearance. Within the hour, the showman knew she was gone. He sent for bodyguards and the Exposition police, and his lies slid out as smooth as butter. He had been startled awake, he said, by “cries of help, coming from Chiquita’s headquarters.” He had thrown on some clothes, raced to her rooms, and, much to his horror, seen “evidences of a struggle having taken place in her room.” There was only one conclusion: Chiquita had been kidnapped. He needed the help of city police. Minutes later, a squad of Buffalo detectives was on the hunt.

The mistake the couple made was to go back to the Exposition. They wanted some things to take on their honeymoon trip, Tony recalled. But when they pulled up to the West Amherst gate, they could see they were done. A Bostock clown, still in greasepaint, moved out of the dark and blocked their way. “He shoved a gun under my nose,” Tony said, and, as the clown wrenched Alice away, he shouted words at Tony whose meaning we can only guess. “You to the weeping willows,” he yelled, and ran off with his prey. Chiquita could do little to resist. “For once,” she said, “I wished I was big.”

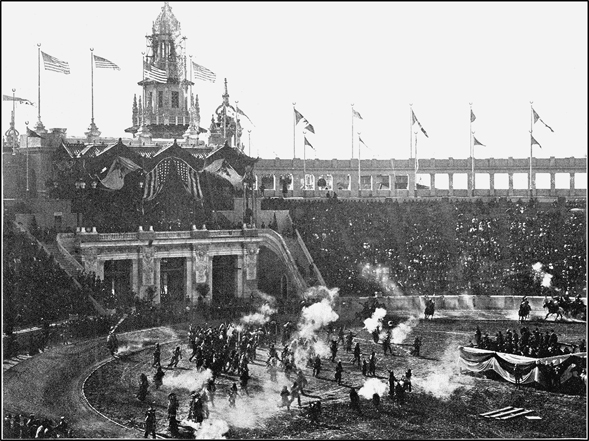

Chiquita and Bostock.

When she was delivered to Frank Bostock, Chiquita cried, and apologized. That wasn’t quite enough for the Animal King, though. He wanted to teach his Doll Lady a lesson. Being four feet taller than she was, and probably two hundred pounds heavier, this was not difficult. He knocked her down, and she fell to the floor, “senseless.” Some of Bostock’s employees wondered whether she would survive.7

VI

THE GRATEFUL GUESTS

Weather forecaster David Cuthbertson, when asked about prospects for Farewell Day at the Exposition, offered a mixed opinion. “There are indications of rain, possibly by tomorrow evening,” he announced, “but there are reports that cause me to hope for a change.” Cuthbertson’s forecast was impossible to get wrong. November second dawned as a sunny day, and the only clouds that appeared were flighty and meaningless.

At the booths and shows on the Midway, the day began with good-byes. Workers who had labored side by side for more than six months offered good lucks for Charleston or St. Louis, exchanged souvenir picture books, and collected autographs. They produced more gifts for their managers—diamond rings, stickpins, and loving cups. And they grew nostalgic. A veteran spieler on the Midway could hardly hold back his tears. The guards, the ticket takers, the chair boys had all done so much, he said, and worked so very hard. “There ain’t very many shows I hates to go way from . . . but this is the exception which proves the rule,” he asserted. He hadn’t expected it, either. “Buffalo people and all the people up in this cold, chilly region are half dead and don’t know it,” he declared. But “give them a little more time than anybody else to do a thing and you will git it done bettr’n anybody else can do it. . . .”8

As Midway performers departed, Buffalo leaders and the press beamed with satisfaction. The fair, they said, had made such a difference for some of these people. They had come to Buffalo untutored, poor-mannered, and unkempt, and, by the end of the season, they had been transformed.

The “Esquimaux,” they said, had been “like so many children.” But now many spoke English and almost every male had bought himself an American suit of clothes. (In fact, many of these Canadian performers had been on the American fair circuit before.) The press claimed that the Filipinos had also blossomed, and some distinguished local women had even taken them into their social circles for meetings and meals. The best part of all was that these newest “possessions” would take recently acquired habits back to their homes. When they returned to their islands, they would introduce civilized customs and convey “the benevolent purpose of the American Government.”

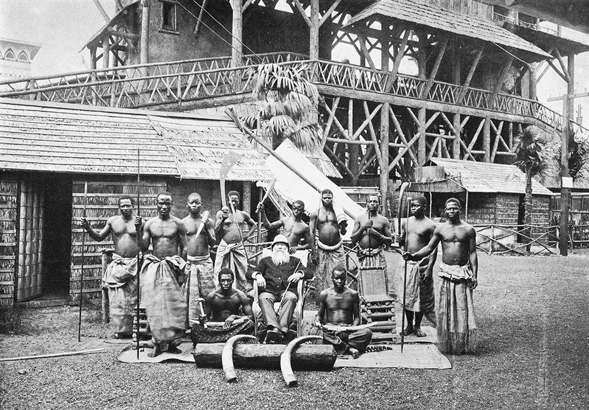

Africans, too, would carry new habits across the Atlantic. “One great ambition of the native inhabitants of Darkest Africa on the North Midway is to be civilized,” commented an Express reporter. There was, he went on, such a desire among the Africans to adopt Western manners and dress that quarrels among performers had sometimes grown violent. “The taunt that Chief So and So was more civilized than some other chief,” he said, “brought out the knives and clubs.”

Another newsman remarked that some African performers, having arrived in a crude and “primitive” condition, now walked the streets of Buffalo “clad as are American negroes, with a bearing that is stronger and better. . . .” He claimed that at least half of the people in the African village hoped to remain in the States. In fact, eight Africans had recently broken away from their guard and were seen boarding a streetcar before they were caught.

Some of the men and women of the Midway villages left with gratitude and envy of America to be sure. And some took away expertise in marketing or technology that they could employ to their advantage at home. Yet many probably had mixed feelings. They had found out what it was like to be dark-skinned strangers in a northern American city. They had been gawked at, scoffed at, and scrutinized. They had spent months performing for people like Mabel Barnes—earnest, well-meaning white people—who had studied them as specimens of subhumans.

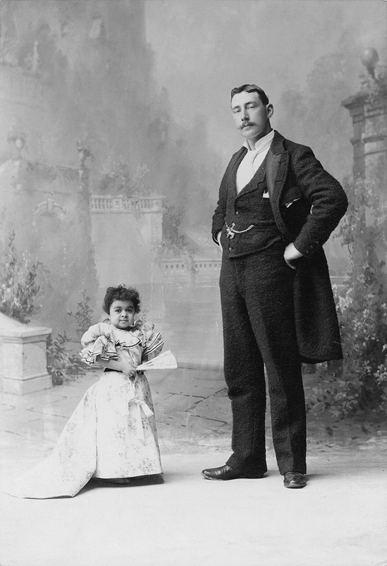

Darkest Africa performers with organizer, Xavier Pene.

It wasn’t just Africans or Filipinos or Indians who found themselves on the opposite side of the looking glass or on the receiving end of stares. Ben Ellington and other Southern performers in the Old Plantation were certainly aware of how much the progressive black community in Buffalo disliked what they did to make money. They were also alert to the way that Northern people, of all backgrounds, dismissed them. Ben reported that his tips from Northern customers were far inferior to those offered by Southerners. He was eager to get back home to Georgia.

Then there were performers who would have been happy to take American “civilization” and to eliminate it altogether. The infamous Filipino Pablo Arcusa had brought to the fair little liking for American beliefs and policies, and another insurgent, Gregorea Tongana, had been discovered in Rainbow City in the fall. A banduris player who deeply resented American occupation of his homeland, Tongana had served on the staff of General Malabar of the Philippine resistance, and he later auditioned in Manila for a part in the band. Other band members knew who he was, and, until he fled, gave him help and cover.

Finally, there were those who never made it home. Historians have explained that this wasn’t just bad luck, but rather a side effect of imperial encounters. Along with guns and money, Westerners had for years carried to indigenous peoples their invisible baggage of germs. In this case, the routes were reversed. In Buffalo, tuberculosis swept through the Indian Congress and sickened eight people. In the Filipino Village, it killed Tastuala Ruyes, twenty-five years old. It also took the life of Henak from Labrador. Mumps infected the Hawaiians and measles hit the Esquimaux Village, striking eleven Natives and killing seven-month-old Sebelia Nikolenik. Others became infected with diseases en route to the Pan-American fair. Social Darwinists at the time said that events like these gave a firsthand demonstration of the survival of the fittest and showed why some groups were vanishing. To them, every death was a lesson in evolution.9

VII

FAREWELL

Mabel Barnes had first clicked through the turnstiles at the Pan-American gates at the very end of April. The grounds had been muddy then, the piles of lumber hard to navigate. She found exhibits closed, gardens bare, and pedestals still waiting for statues. Now, thirty-three visits later, on a cool, sharp-edged November day, she had come full circle. The city she had loved was on the verge of disappearing. She wandered by boxes, barrels, and overturned dirt. One building, the stately New England exhibit, had been gutted by a fire, and workmen with crowbars and axes wrenched apart its porch. Others, like the sixteen buildings in Bostock’s show, had been auctioned off two days earlier. Esau’s quarters and Chiquita’s living and reception rooms, along with animal skins—from lions, tigers, panthers, leopards, and jaguars—had been sold.

The schoolteacher entered the fair alone that final day, joining 125,000 others on the grounds. She walked to the New York State Building, where, four months earlier, she had waited on tables at a reception for fellow teachers. She took a last look at the Esplanade and the Court of Fountains. Abby Hale then met her, and together they said good-bye to the big exhibition buildings. As usual, the women saved the Midway for last. They wanted to see one final show—the one that had enthralled them more than any other: Darkest Africa. But it was too late. The stockade surrounded a deserted encampment. “To our disappointment,” Mabel said, “we found [it] empty and forlorn.”

They went back to the Electric Tower and “feasted [their] eyes on the beauty of it.” They tried more buildings and found more of them locked.

As the two women toured the grounds that afternoon, they would have noticed crowds clustering around special visitors. Carrie Nation was said to have been there. Audiences loved showing how much they hated Mrs. Nation, with her loud opinions and saloon-smashing attacks against the devil, alcohol. The six-foot-tall temperance reformer, who spent much of her outspoken life in handcuffs, would have met plenty of enemies at the Pan-American. Two months earlier, while lecturing at Coney Island, Nation had fixed her fierce opinions on President McKinley, who at the time lay injured in Buffalo. She said publicly that she was “glad” he had been assaulted. “The President was a friend of the rumsellers and the brewers,” she declared, “and therefore did not deserve to live.” When the New York audience hissed at her, she told them they were “hell hounds and sots.”10

Abby Hale and Mabel Barnes had no time for the likes of Mrs. Nation. They also skirted another celebrity. Holding court on the West Esplanade bandstand, with her big oak barrel, a black cat, and Captain Billy Johnson, was Annie Taylor.

All her work over the previous weeks—the attention, money anxieties, and most of all the most frightening ride of her life—had brought Taylor to this triumphant moment. Resplendent in a blue jacket, and showcased next to Iagara, the cat that allegedly had preceded her over the falls, Taylor began greeting people around noon. She took particular time with children and those “who displayed enthusiasm above the average.” She also tried to make it clear she was not putting on an act at the Exposition, like Midway performers. She was, for the sake of $200, “receiving” visitors.

And what a reception it was. Around and behind her, a line snaked with curious and admiring (and paying) guests. Thousands of people of all sorts—“a continuous stream of humanity”—had come to meet her. Exposition guards, reported a witness, “had their hands full preventing crushes.”

Observers said she showed signs of her ordeal. Her nose was red, and she looked ill. She didn’t want to shake hands—her doctor, she said, advised against it. And she admitted that she ached. “I am very much bruised as the result of my trip,” she said to a reporter. “The muscles of my back, between the shoulders, are particularly sore.” She couldn’t stand the cold, either, and had to stop and warm herself now and then inside the Temple of Music. All in all, one reporter commented, Mrs. Taylor seemed rather the worse for wear. He also thought she had not aged particularly well. “Mrs. Taylor looks fully the 43 years that she admits,” he commented.

Annie Taylor had won her first battle—she had subjugated Niagara Falls just as surely as the rich men who had diverted its water for modern technology. But she was struggling in her second battle—her fight for dignity. She had received plenty of compliments, to be sure. “All who have met and talked with her agree upon two points,” said the influential Buffalo Express. “She is certainly the best-educated and most refined appearing person who has ever attempted a feat of daring at Niagara. And she is (or was before her violent experience) the calmest, most self-possessed of all the great multitude of adventurers commonly classed as Niagara Falls cranks.” The Express also described her as “modest and sensitive.” Other papers called her the bravest woman in the world and suggested that she had put to shame other male Niagara daredevils, like Carlisle Graham. One columnist also pointed out that, given as she was driven to desperation, she chose a more honorable route than suicide. She had simply sought a “competency for the remainder of her days.”

Still, there were plenty of people who maintained that Mrs. Taylor’s barrel ride revealed nothing more than dumb luck and cheap showmanship. “The net results of the hazardous trip,” wrote the Grand Rapids Herald, “is that Mrs. Taylor has acquired a little notoriety, which she can capitalize to the extent of becoming a dime store freak.” Other newspapers called her “reckless and selfish” and ridiculed her audiences. “The country is filled with people who are just morbid enough to crave a look at her,” remarked one paper.

As the general public debated Taylor’s character and judgment, the distinguished women of Buffalo seemed to ignore the adventurer. They spent the final days of the fair in the elegant confines of the Women’s Building, enjoying last luncheons, toasting each other with crystal, and nodding and smiling over bouquets of pink cosmos.11

As dusk approached on Farewell Day, Mabel Barnes and Abby Hale ate a picnic and walked together toward the Triumphal Bridge. The November sky, cold and luminous, performed its own send-off at sunset, and then, at a little after 6 p.m., the Illumination took over. Every band on the grounds struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The women could not get enough of the scene. “We looked and looked and looked,” said Mabel. The schoolteacher rarely repeated herself, so it must have been a powerful moment. They wanted to stay until midnight, when John Milburn would throw his extinguishing switch. But Mabel knew what the end of a fair usually brought with it, and already she could see signs of destruction, as rambunctious visitors began to rip up flower beds. Not willing to get caught in the mayhem, and perhaps not willing to see the ruination of everything she had admired, Mabel went with Abby through the Midway one final time. Then they left.

The women knew what they were doing. Even before they walked out, scavengers began raiding buildings for food and tore away signs and banners and decorations. In the Illinois display, said one witness, crowds swept the guard “aside like a fly” and men held him down while they stripped the apple exhibit of every piece of fruit. In the chrysanthemum exhibit, “souvenir fiends” took every flower.

For those who could concentrate on it, the fireworks show proved stupendous. At 8 p.m., on Park Lake, the reliable James Pain sent up a sky-full of meteors and let loose a shower of exploding stars, rockets, and shells. He lit up a portrait of John Milburn and re-created the bombardment of San Juan. At the very last, he sent up a poignant set of illuminated words: FAREWELL TO THE BEAUTIFUL CITY OF LIGHT.12

The final tribute to the fair, delivered at 11:30 p.m. in the rotunda of the Temple of Music, was, according to at least one listener, “a funeral oration.” The mourners, huddled against the evening cold, included Latin American representatives, state commissioners, and all the fair’s backers and planners.

Mayor Conrad Diehl spoke first. He accepted the gift of the Temple of Music organ—one of the few valuable souvenirs the city would retain—from Buffalo’s James Noble Adam. He then turned over the podium to the man, once his political adversary, who had since become his trouble-tested colleague: President John Milburn. “We started out,” Milburn said to the group, to “begin the 20th century by a binding of the relations of the free peoples of North, Central, and South America. . . .” This, he said breezily, had been accomplished, and he thanked the Latin American emissaries. And this land, he went on, gesturing at the grounds, “was once a plain and a scheme.” But it had become “one of the most beautiful scenes that the human eye ever has looked upon.” He thanked the people who built the fair.

Then he entered rockier terrain. “The exposition,” he announced, “has been a great success.” Was there a collective intake of breath? Milburn knew insolvency was on everyone’s mind, but he refused to give in. He would not use the word failure. “If it has been a financial unsuccess,” he said, “it has been worthy of all praise.” He tried it again. “. . . I believe that what financial unsuccess there is about it the citizens of Buffalo will meet with the same energy and generous spirit by which they constructed the exposition.” At the very least, he asserted, “we have made Buffalo known to the United States as it never was known before.”

Milburn finished speaking just before midnight, and, with a smaller group of men—including Director of Works Newcomb Carlton and Henry Rustin, mastermind of electricity—he walked to the Triumphal Bridge. High up in the Electric Tower, eight army buglers rang out “Taps.” Except for some muffled weeping, the grounds were still. Milburn touched a button on a box. Connected to the Exposition’s rheostat, it sapped the power from the fair’s 160,000 incandescent bulbs. Gold to crimson they went, and then shell pink to pinpoints. The Exposition became so dark, said one witness, it seemed like stars had “fallen into a sea of ink.”

The end, a reporter wrote, was “apparently painless.” It is hard to know why he used personification to describe the final moments of the Exposition, but, then again, death and electricity had been so tightly linked that autumn it was perhaps unavoidable. Rainbow City perished, he said, “like a fair queen, a lovely lady, from whose cheeks the color faded, in whose eyes the luster died, on whose lips the bright smile vanished. The darkness of night enveloped her like a funeral pall. She did not struggle, no sigh, no moan. The fountains of her life fell and grew fainter, until they stopped.”

To the less overwrought, it simply became very, very dark. Fairgoers made their way to the exits, some of them stopping to remove tiny lights and take them as souvenirs. On the Midway, other visitors began to act out. They smashed booths, threw restaurant chairs, and fought each other with vines and branches, plants and palms. They threw confetti until they waded in pools of paper. They took food and fruit, ripped feathers from Indians, and wrested flowers from Hawaiians. Twenty-five of them became the last patients at the Exposition Hospital.13

While crowds surged through the Midway, behind the doors at Bostock’s Wild Animal Arena, Chiquita prepared for the night. She had entertained audiences all day long. If she carried any bruises on her body, they were concealed, and if she was distraught, she had put on a brave face. She had moved through her drawing-room act as though nothing had happened. It wasn’t as though she had any choice. “I was taken possession of,” she said.

For Frank Bostock, the outlook was bright. Having spent months grooming the press, he was able to shape the story of Chiquita’s flight to his liking. Tony Woeckener, he explained, had facilitated the abduction of Chiquita, and he had been arrested. A competitor on the Midway had sought to undermine the Animal King, and Tony had been the “tool” the schemers used. Thankfully, a loyal employee had intervened and rescued the little performer. So happy was he to have order restored, he decided not to bring charges against the “kidnappers.”

As for Chiquita’s affection for the cornet player? “Chiquita has had these little attachments frequently,” he told reporters. “Then when the suitor thinks he’s the whole thing, her love grows cold.” And the wedding? It had been forced. The Woeckener boy and his friends had taken Chiquita to dinner and had fed her some wine before driving her to the judge. Even she would admit she was in a “batty state.” Chiquita was worth a lot of money. She had thousands of dollars and jewels. Who wouldn’t want to marry her? The Animal King announced he would do what he could to protect her from these sorts of manipulators in the future.

That protection, in fact, would begin right away. Aware that Tony had begun to protest, the showman would put Chiquita out of his reach. Luckily for Bostock, this was Buffalo. Canada was only a river away.14