| 20 | In the Eye of the Beholder Projective Geometry |

As the liberating trends of the Renaissance spread throughout Europe, prompting scientists and philosophers to explore the world around them with renewed vigor, artists searched for ways to mirror that reality on paper and canvas. Their main problem was perspective — how to portray depth on a flat surface. The artists of the 15th century realized that their problem was geometric, so they began to study the mathematical properties of spatial figures as the eye sees them. Filippo Brunelleschi made the first intensive efforts in this direction, and soon other Italian painters followed suit.

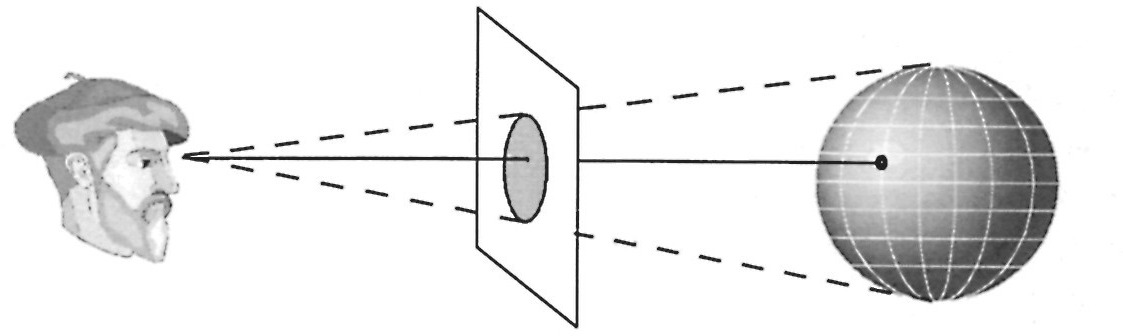

The most influential Italian artist in the study of mathematical perspective was Leone Battista Alberti, who wrote two books on the subject. It was he who proposed the principle of painting what one eye sees. That is, he thought of the surface of a picture as a window or screen through which the artist views the object to be painted. As the lines of vision converge to the point where the eye is viewing the scene, the picture on the screen captures a cross section of them. (See Display 1.)

Display 1

Alberti developed a number of mathematical rules for applying this principle. He also posed a fundamental question: If an object is viewed from two different locations, then the two "screen images" of that same object will be different. How are those images related, and can we describe their relationship mathematically? The screen images are called projections of the object; the study of how projections are related became the motivating question for a new field of mathematics called projective geometry. Among the most prominent people of the 15th and early 16th centuries who studied, used, and advanced this mathematical theory of perspective were Italian artists Piero della Francesca and Leonardo da Vinci, and also the German artist Albrecht Dürer, who wrote a widely used book on the subject.

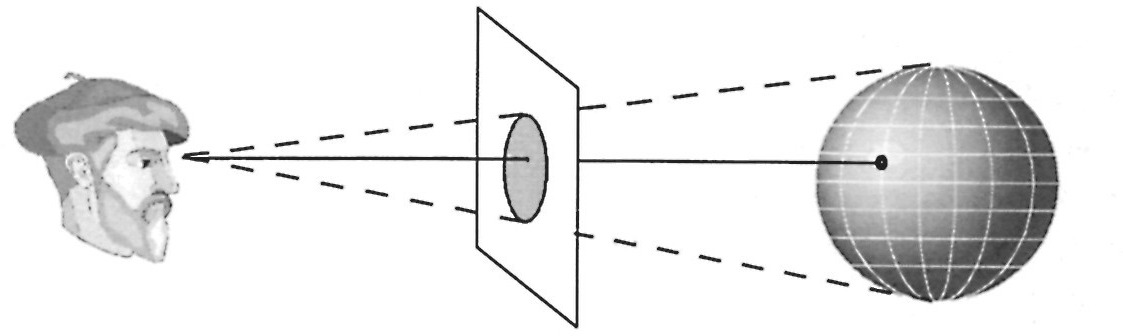

Now think of projections "in the other direction," so to speak. That is, think of the "eye" as a light source that projects a figure on one plane to its image on another, just like a slide projector shows a figure on a film slide as an image on a screen. If you tip the screen, you can distort the image in lots of different ways. (See Display 2.) You can change distances and angles, for instance, but there are some fundamental properties of figures that you can't change. For example, a straight line will always project to a straight line.

Display 2

Here's a more striking example: The image of a circle may not be a circle, but it will always be a conic section.1 In fact, the image of any conic section will always be a conic section! This remarkable property of conic sections was the basis for a groundbreaking study of projections by French engineer and architect Girard Desargues. Desargues's work was generally overlooked in his day but was rediscovered and finally appreciated in the mid-19th century. By then, Jean Victor Poncelet had published a very influential book on projective geometry, which he had planned (without benefit of any reference books) while he was a Russian prisoner of war after Napoleon's defeat at Moscow.

Building on the work of Desargues and Poncelet, a number of 19th-century French and German mathematicians turned projective geometry into a major field of study. Their mathematical generalizations of the ideas of perspective and projection led to some surprising insights. One of the most striking and powerful is the principle of duality.

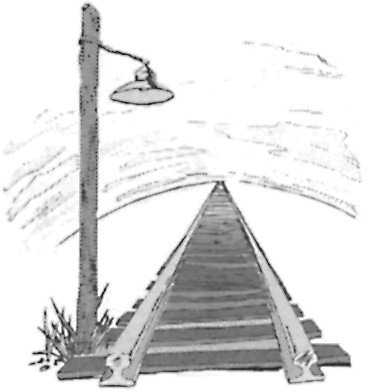

To explain this idea, let's step back for a moment to the artist's view of projections. A well-known example of perspective drawing is the image of railroad tracks stretching away to a distant horizon. The tracks, which are parallel, appear to meet at a point at or just beyond the horizon. In fact, on the plane of the artist's canvas, these lines do meet. That is, in order for these lines to appear to be the same distance from each other as they recede from the viewer, they must meet "at infinity." All the lines that appear to be parallel to a particular line should meet at the same point at infinity. Projective geometry takes those points at infinity seriously. The plane of two-dimensional projective geometry is the regular Euclidean plane with an extra line added — an ideal line that contains exactly one point for each "family" of parallel lines in the Euclidean plane.2 In this way, every pair of straight lines in the projective plane crosses at exactly one point.

This brings us back to duality. In Euclidean geometry, "Two points determine exactly one line" is a well-known fact. It is true in projective geometry, too, and so is "Two lines determine exactly one point." In fact, any statement about points and lines that is true in projective geometry remains true if the words "point'' and "line" are interchanged (assuming that you make the appropriate adjustments in terminology). This is the principle of duality, and each of the two statements is called the dual of the other. It was first recognized in the middle of the 19th century and established definitively early in the 20th century by constructing an axiom system for projective geometry in which the dual of each axiom is also an axiom.

For example, here is an axiom system for plane projective geometry in which each axiom is its own dual:3

1.Through every pair of distinct points there is exactly one line, and every pair of distinct lines intersects in exactly one point.

2.There exist two points and two lines such that each of the points is on only one of the lines and each of the lines is on only one of the points.

3.There exist two lines and two points not on those lines such that the intersection point of the two lines is on the line through the two points.

The fact that Axiom 3 is its own dual may not be obvious at first. However, keep in mind that the intersection point of two lines is the dual of the line through two points. Now if you interchange "point" and "line" in Axiom 3 and make that language adjustment, you can see that the resulting statement says the same thing: "There exist two points and two lines not on those points such that the line through the two points passes through the intersection point of the two lines."

The dual statements we have presented so far don't illustrate the power of duality very well; they're too simple. Here is a more interesting example, the so-called "mystic hexagram" theorem of Blaise Pascal, which stemmed from the work of Desargues on conic sections:

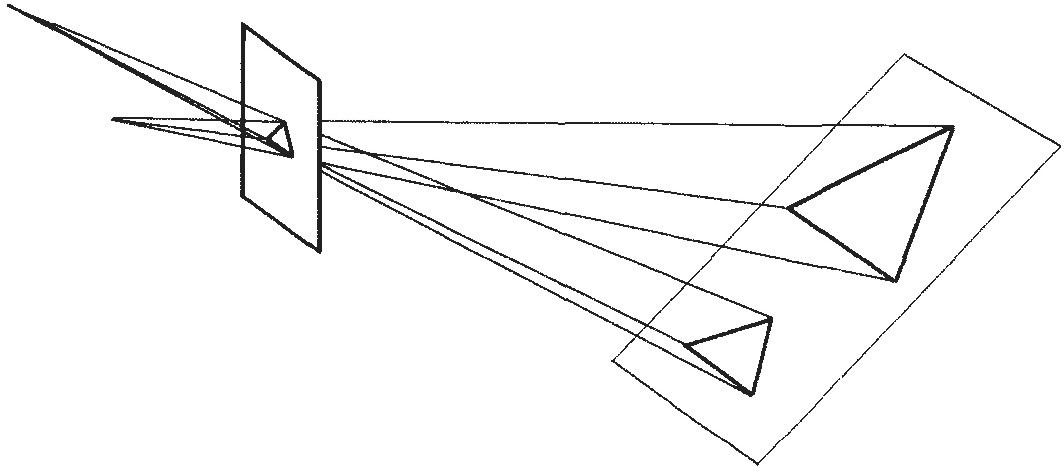

A hexagon can be inscribed in a conic section if and only if the points (of intersection) determined by its three pairs of opposite sides lie on the same (straight) line. (Display 3 illustrates Pascal's theorem for an ellipse.)

Display 3

Applying point-line duality, the sides of a polygon become the vertices and vice versa, and "inscribed" (vertices lie on the conic) becomes "circumscribed" (sides are tangent to the conic). Thus, the dual of Pascal's theorem is:

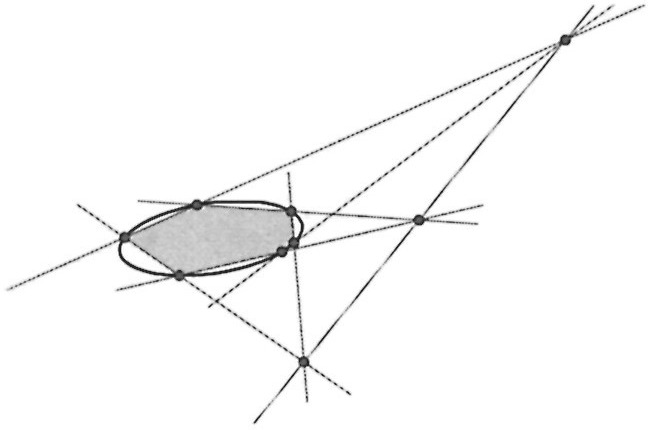

A hexagon can be circumscribed about a conic section if and only if the lines determined by its three pairs of opposite vertices meet at the same point. (Display 4 illustrates the dual of Pascal's theorem for an ellipse.)

Display 4

A proof of this theorem was first published in 1806, more than 175 years after Pascal (at the age of 16) had stated his mystic hexagram theorem but before the principle of duality was understood. By duality, we now know that any proof of either theorem automatically guarantees the truth of the other one, too!

For a Closer Look: See [58] for more on projective geometry. Look at [61] and [6] for the early history of perspective. For the history of projective geometry in the 19th century, the best source is [79],

1 The conic sections are circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas. See Sketch 28.

2 Each family of parallel lines can be related to a single real number, in much the same way as all the lines of each family are related to their common slope.