THE peculiar destiny of the Celts had carried them in a few centuries over the greater part of Europe, of which they had conquered and colonized a good third—the British Isles, France, Spain, the plain of the Po, Illyria, Thrace, Galatia, and the Danube valley, in addition to Germany, almost to the Elbe, which was their cradle. In a still shorter time they had lost all their Continental domain and part of the British Isles, being reduced to subjection in one place, driven out of another, and everywhere deprived of all political power. Then there had been a respite. But from the sixth century onwards the independent states in the British Isles were subjected to unceasing attacks, to which they succumbed. Only one is reviving, Ireland. The political creations of the Celts are among the great failures of the ancient history of Europe. The historical role of the Celtic peoples, except the Irish, for whom the future is opening again, is a thing of the past. I have tried to suggest that that role was once a large one, and that much of it remained. Certainly this was the feeling of their opponents. One has only to try to imagine what the history of the Celts would have been if Cæsar had not described the resistance of Vercingetorix and the Anglo-Normans had not adopted Arthur. But also how little evidence the Celts have left of themselves, compared with what we know of the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, even the Germans ! Even now, there may be some who fear, when confronted with this history, which has left so few monuments but which we are none the less tempted to regard as great, that they are the victims of a mirage produced by the imagination of Greek and Latin writers and the fancy of Celtic archaeologists. One last check is needed, that of language.

There are still Celtic languages in existence, but they are no longer, as it were, languages working full time, completely sufficient for the social life of a whole society and, what is more, sufficient to themselves. Irish, it is true, has once more become an official language, now that Ireland is once more a political community. But many Irish patriots have had to learn their language anew. The example of Breton is still more striking ; it is the mother-tongue of a dwindling part of the population and a learned or rather a poetic language for a few lovers of the past. In different degrees, all Celtic languages were in this state. The difference which we see in the case of Irish and Welsh is due to the existence in both countries of an older and richer literary tradition. These various languages borrowed largely from all those which brought them into contact with a new life, particularly Latin. The degree of their independence is proportionate to the extent to which the peoples who spoke them resisted those who sought to assimilate them. They did not maintain themselves in their original independence and dignity.

But the Celtic languages are no longer spoken save in a very small part of the regions in which the Celts have left descendants. Great numbers of Britons remained in Britain after the Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman conquests. Celts also remained in Gaul, where they formed the basis of the population. Many certainly remained in Spain and Northern Italy. But it is interesting to note how many remnants of Gaulish were preserved in Low Latin and French.

For Gaulish did not vanish as if by magic, quickly though Latin spread in Gaul.1 A preacher like St. Irenaeus still had to learn it at the end of the second century,2 and the Emperor Alexander Severus seems to have understood it.3 In the time of Ulpian, the beginning of the third century, it was possible to draft certain acts in Celtic.4 In the fourth century, St. Jerome could compare the speech of Treves and that of the Galatians. Sulpicius Severus in the fifth century perhaps knew a little Celtic,5 and Ausonius, Gregory of Tours, Fortunatus, and Marcellus of Bordeaux 6 knew a few words each. This evidence is confirmed by inscriptions. Celtic continued in use for a long time, but in circles which grew ever smaller. Still, in abandoning their language, the vast majority of Gauls kept their manner of speaking and a great number of words for which Latin gave no equivalent.

Thus, Gaulish had lost u ; the Gauls did not take up the Latin u, pronouncing it u.7 In the syllable um in the genitive plural and accusative singular masculine of stems in u or in the nominative and accusative singular neuter of the same stems, they gave it a sound rather like o, which assimilated these terminations to Celtic terminations in om. They said dominom. So, too, they kept certain methods of noun-formation which were peculiar to their language, which formed adjectives in -acos. Names of fundi and some other words were formed in -acus.8 Certain words passed into the Latin vocabulary, such as cantus, the iron felloe of a wheel, from Gaulish cantos9 (Welsh cant “ circle ”).10 Others survived in the Latin of Gaul, such as esox “ salmon ” (Welsh ehawk, Irish eo), cavannus “ owl ” (Welsh cuan). A large number of these relics remained in the Romance languages and some in French, in addition to the geographical names, proper or common nouns, which remain in languages as fossils. Gaulish left to the Romance languages names of plants like verveine (verbena), beasts like alouette (lark), and others. Clock and cloche (bell) are Celtic (Low Latin clocca, Old Irish cloc) ; bells were worn by animals, but in Ireland only by those of nemed or holy men. Cruche (jug) is of Celtic origin (Irish crocan, Welsh crochan). Bar, tringle, barque, beret, chimney, and birelta, and their French equivalents all come from Gaulish, and so do chemin and bief (mill-race). M. Dottin has made as full a list of these words as possible but it is not yet complete, and research among local patois will increase it.

On the whole, a great deal of Gaulish has survived in the Romance tongues. When one people progressively adopts the language of civilization of another people which rules it, it never completely gives up its own ; the two languages become blended. Latin must have been spoken in Gaul in the same way as French in Périgord. First people go over from one language to another ; then a time comes when a mixed tongue comes into being. To a certain extent, French stands in the same relation to Gaulish as the English dialect of the Lowlands to Gœlic.

So the Celtic languages survive in two ways, in structure (but with the admission of many foreign elements) or in the shape of single elements embedded in languages of other structures. Everywhere there is something left of them, but they were only the remnants of a vanishing life until the revival of Irish, because the Celtic societies had not lasted as Celtic nations and states. The language will be saved by the Irish Free State.

Such, as I said, has been the pecular fate of the Celts ; they were unable to create lasting states, and their languages have survived only in a partial and diminished condition. But that original, vigorous race, although it failed politically, chiefly through having no sense of the state or an insufficient sense of discipline, made very great contributions to civilization, to industry, art and, above all, literature. The La Tène craftsmen were masters in the arts and industries in general, and particularly in jewellery, and the earliest tellers of the Celtic epics showed a feeling for heroic poetry, a sense of the marvellous, mingled with humour, and a dramatic conception of fatality which truly belong to the Celts alone. Gaston Paris made the profound observation that the romance of Tristram and Yseult has a particular sound, which is hardly found elsewhere in Mediaeval literature, and he explained it by the Celtic origin of these poems. It was through Tristram and Arthur that all that was clearest and most valuable in the Celtic genius was incorporated in the mind of Europe. And that tradition has been kept up by the unending line of poets and prose-writers of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Brittany who have adorned English and French literature by bringing to it the genius of their race.

I said above that the historians of France, who wrote such a peculiarly fine history, had in them the spirit of the Celtic race. But the very story which they were telling, the history of that undestroyable people of peasants, warriors, and artists, with its glories and tumults, its hopes and enthusiasms, its discords and rebirths, is surely the story of a nation whose blood and bones are mainly composed of Celtic elements.

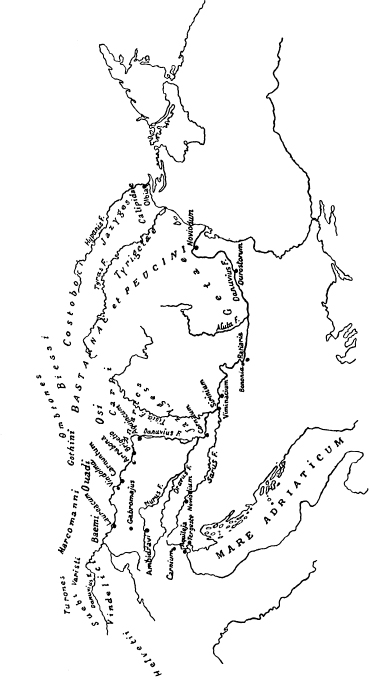

MAP 2. The Celts of the Danube