Narrow-Gauge Locomotives 1871–1971

In order to understand the overall contribution made to the historical and technical development of narrow-gauge locomotives by events at the Royal Arsenal, certain observations should be made relating to the state of affairs in this field that prevailed immediately prior to the first locomotive’s acquisition for use on the Arsenal’s railway system. Although much is rightly made of the importance of the early George England-built locomotives for the Ffestiniog Railway, it should be remembered that they were in no way the earliest narrow-gauge steam locomotives and that even by the 1840s Messrs Vulcan Foundry & Co. had supplied four 2ft 6in-gauge steam locomotives to the War Department for the purpose of hauling artillery. Sadly, the maker’s drawings of these locomotives do not survive, and their construction preceded both the dawn of railway photography and the widespread circulation of professional journals relating to engineering matters in general, let alone narrow-gauge locomotive design. All that is known of them is that they were completed in 1845 to two designs: Works Nos 213–4 were of the 0-4-0 wheel arrangement with 10in x 16in cylinders and 2ft 9in diameter coupled wheels, while Works Nos 215–6 were 0-4-2s with 11in x 18in cylinders and 3ft coupled wheels. As far as it is known, these were the first locomotives constructed in the United Kingdom specifically for military purposes, but it is not known how long they remained in use. What can be said with certainty, however, is that owing to the lack of publicity surrounding them, any useful lessons that could have been learned during their construction and from their subsequent operation were lost to the engineering world at large, a fact evidenced by some of the design proposals put forward in connection with the introduction of steam locomotives on the Ffestiniog Railway.

The period between 1845 and 1863 saw the appearance of a number of narrow-gauge designs, many for gauges of between 2ft 6in and standard, and these included such diverse examples as the 4ft-gauge inclined cylinder 0-4-0s for the Padarn Railway, a 3ft-gauge Neilson ‘Box Tank’ 0-4-0ST with only one (rear-mounted) cylinder, and a 2ft 8in-gauge 0-4-0ST design from Messrs Fletcher, Jennings & Co. of Whitehaven that was eventually developed into the first locomotive for the Talyllyn Railway. One problem for the future development of non-articulated narrow-gauge steam locomotives that was immediately apparent from examination of the design of the England 0-4-0 tank locomotives of the Ffestiniog Railway was that these locomotives’ firebox proportions precluded the use of full-length one-piece mainframes. Indeed, on these locomotives the drawbar loading was passed directly through the firebox wrapper, a situation that was only altered in more recent years on Prince by strengthening the footplate valences in order to relieve unwanted stresses. The first of the 18in-gauge locomotives for use at Crewe Works, 0-4-0ST Tiny, essentially reverted to much of the constructional layout used in the single-cylinder Neilson ‘Box Tank’, save for the use of two inside cylinders (mounted in the conventional position) and a simplified cylindrical firebox crosssection. With Tiny, therefore, a point of development had been reached where full-length inside mainframes were adopted at the expense of using a non-depending firebox with all its structural and steam-raising limitations.

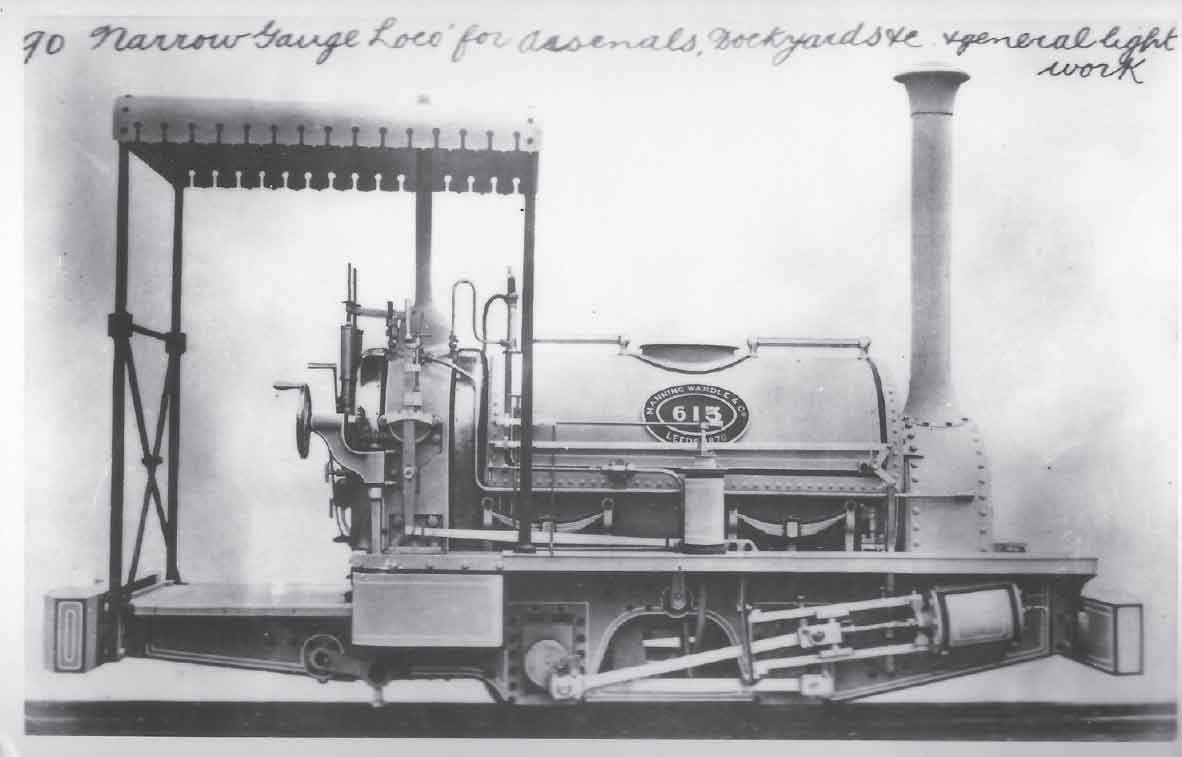

Tiny’s design was adopted in commercial form outside the railway workshop sphere on only two occasions: the 18.5in-gauge Works No. 2079 of 1870 Little Dorrit (shown in the accompanying drawing and photograph), and five years later in 1ft 10in-gauge form as the first locomotive on the Guinness Brewery Tramway in Dublin. However, a modified 2-2-0ST version, built for the Copiapo Mining Co. in Chile by Black, Hawthorn & Co. in 1887 to 1ft 8.5in gauge survives today (presumably width restrictions precluded the fitting of coupling rods), as do replicas of the Great Laxey Lead Mining Co. 1ft 7in 0-4-0Ts Ant and Bee, a much-modified ‘derivative’ design. The specification was adapted by Francis Webb at Crewe to produce a design of locomotive (initially powered by a Brotherhood three-cylinder motor, but later by two conventional cylinders fitted with footplate-controllable slip eccentric valve gear) with driving footplates and equal overhangs at both ends. This design even appeared at the Arsenal in 1878 (Fox Walker Works No. 386) as we saw in Chapter Two. Beyer Peacock & Co. Ltd went on to produce the most successful of the ‘railway workshop’ 18in designs: a 0-4-0WT with conventional cylinders and valve gear, inside frames, cylindrical firebox and unequal overhangs that was adopted (eventually in saddle tank form) by the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway at Horwich. Today, two locomotives of this design survive: the Beyer Peacock works locomotive Dot (No. 2817 of 1887) in virtually ‘as built’ condition, and the ex-L&YR Wren (No. 2823 of 1887) which is preserved in modified form as a saddle tank.

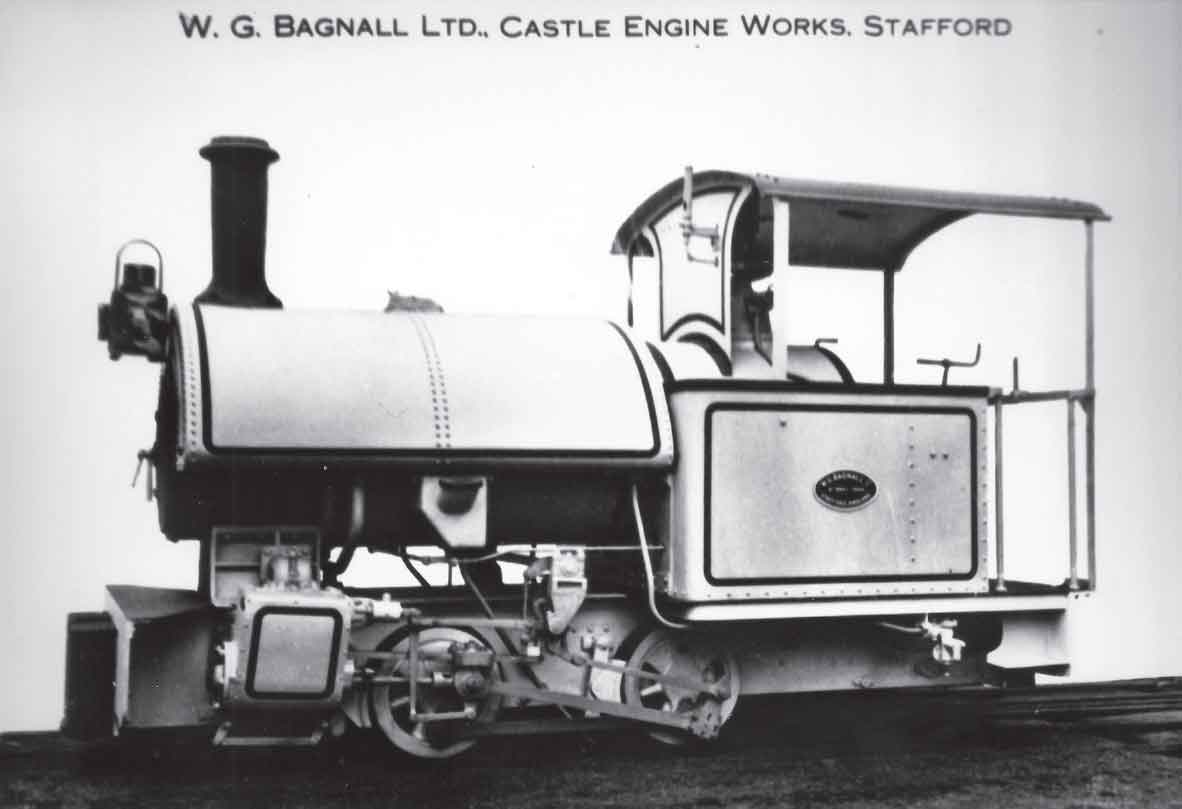

Although the inside-framed locomotive with a nondepending firebox was eventually adapted by W.G. Bagnall & Co. of Stafford into the ubiquitous ‘Bullhead’ boiler 0-4-0ST locomotives familiar today, this locomotive dynasty offered only limited opportunities for development into larger designs. The earliest reliably documented movements in a totally different direction for sub-2ft 6in-gauge locomotive design were made by Isaac Watt Boulton of Ashton-under-Lyne in 1861–4. Boulton produced two 2ft-gauge 0-4-0STs with geared transmission and full-length outside mainframes allowing for a proper locomotive pattern firebox of reasonably generous proportions. The use of gearing was not widely adopted and Boulton did not go on to turn his initial efforts into a coherent strategy for marketing direct drive variants of these locomotives, but they were considered of sufficient merit to warrant mention in Engineering’s discussion of Tiny in 1866. In the end, it was left to two neighbouring Leeds companies to establish a line of locomotive development that was to have a major impact on the course of narrow-gauge railway history worldwide. In 1870, Hunslet Engine Co. turned out a 0-4-0ST locomotive Dinorwic for use on the village tramway line associated with the Dinorwic slate quarries in North Wales. The engine, Works No. 51, possessed full-length outside frames, outside cylinders, a locomotive-type boiler and direct drive and its features were noted in The Engineer soon after construction. The locomotive, as was to be expected, was well-made and equipped with many of the features associated with its wider-gauge brethren. From the point of view of the wider adoption of its constructional principles, it was handicapped by its overall size (including 9in x 14in cylinders and a 4ft 3in wheelbase) and by the fact that the horizontally-mounted cylinders and steamchests were prone to damage from obstructions, especially the steamchest-mounted cylinder drain cocks. As a consequence of these observations, Dinorwic’s design was duplicated only once, as George (Works No. 177 of 1877) for the same customer. For this reason, it can be stated that although Hunslet had struck the crucial technical blow, there still remained the commercial hurdle of producing a locomotive that was sufficiently compact to satisfy the requirements of many potential industrial customers. Nonetheless, Dinorwic and George were relatively long-lived, lasting until 1936 and into the Second World War respectively, although both were out of use for long periods at the end of their careers.

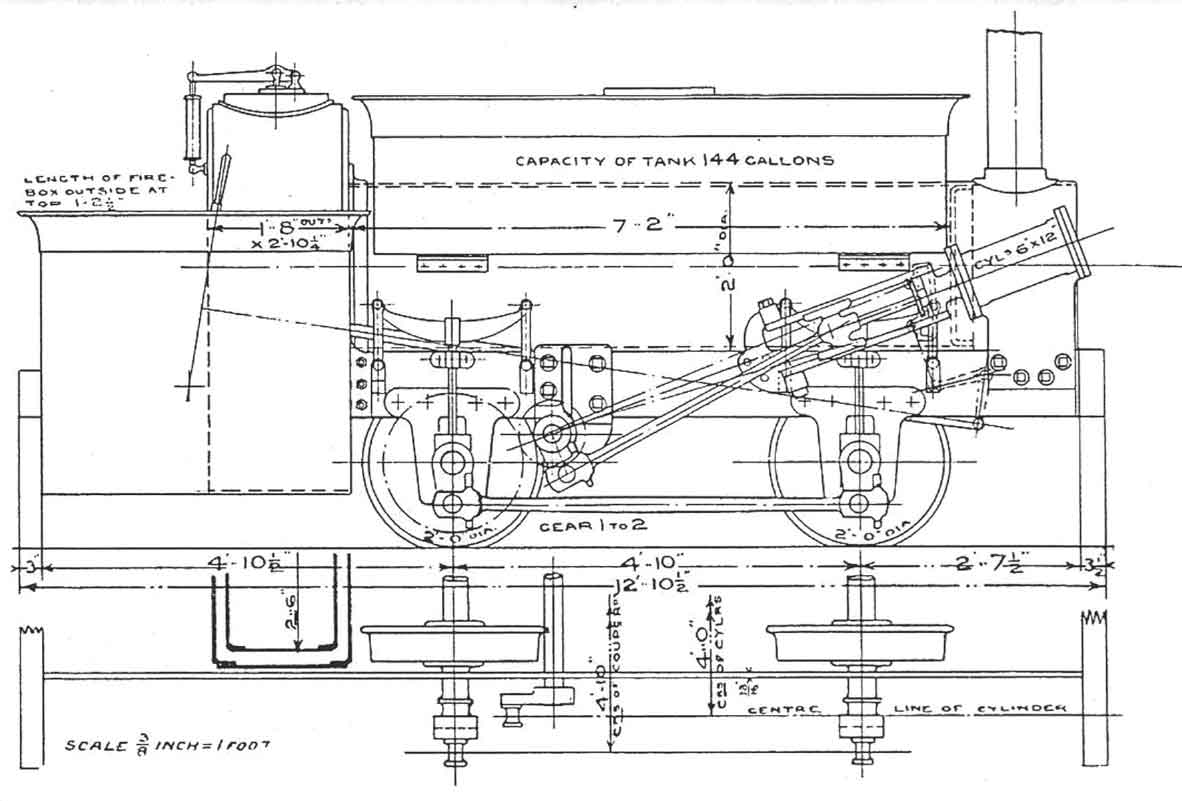

This drawing shows the locomotive supplied by Isaac Watt Boulton in 1861 for use on a 2ft-gauge line at Cross, Gidlow and Swanling Colliery, Wigan. This engine was allegedly a rebuild of a standard-gauge machine of 1856. The use of full-length outside mainframes directly attached to both bufferbeams is readily apparent. (The Locomotive)

The accompanying drawing shows Lilliputian, another I.W. Boulton product, built in 1864 as a development of the previous 2ft-gauge locomotive. The gauge, geared transmission and full-length outside mainframes were common to both locomotives. (The Locomotive)

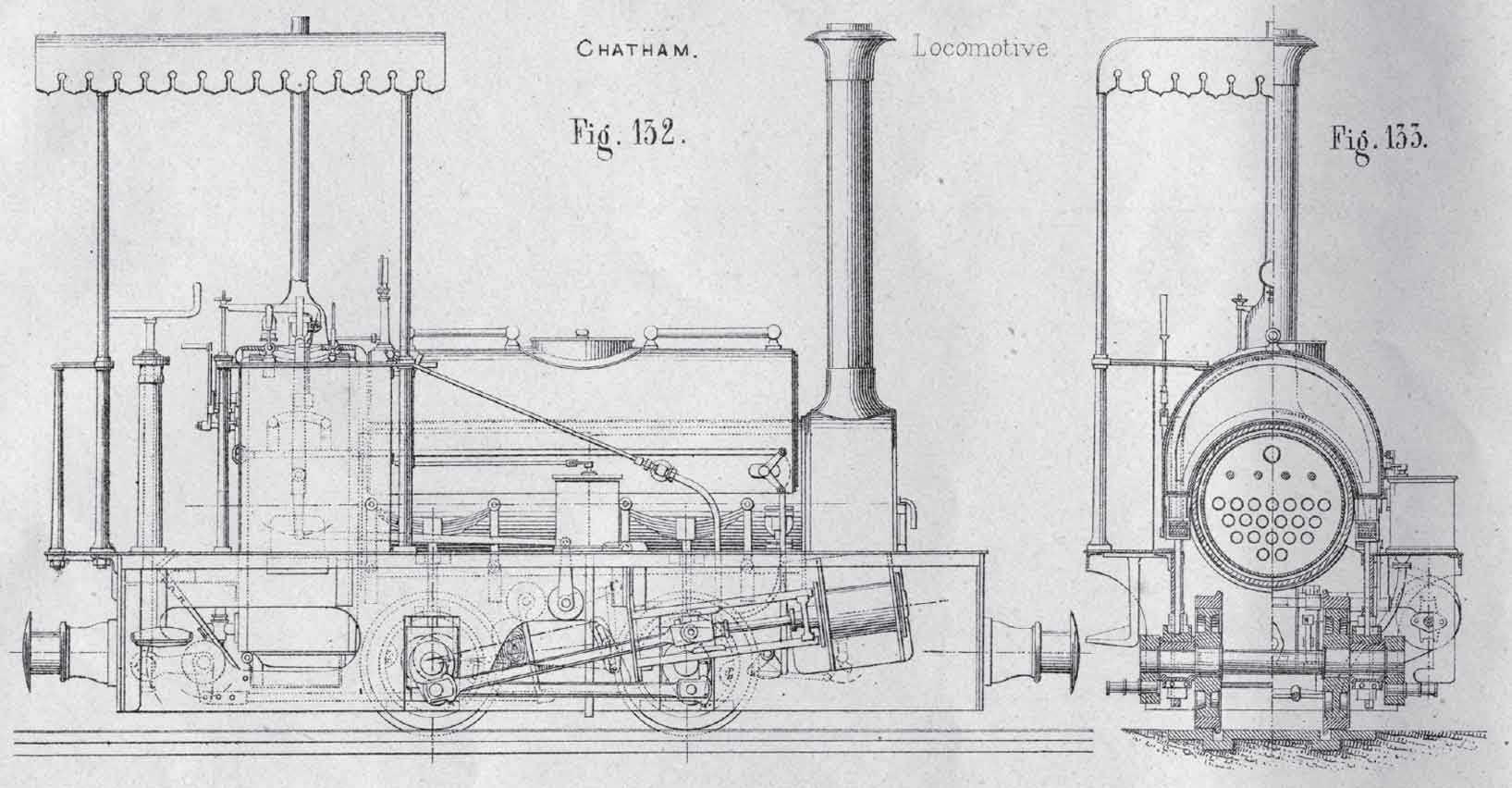

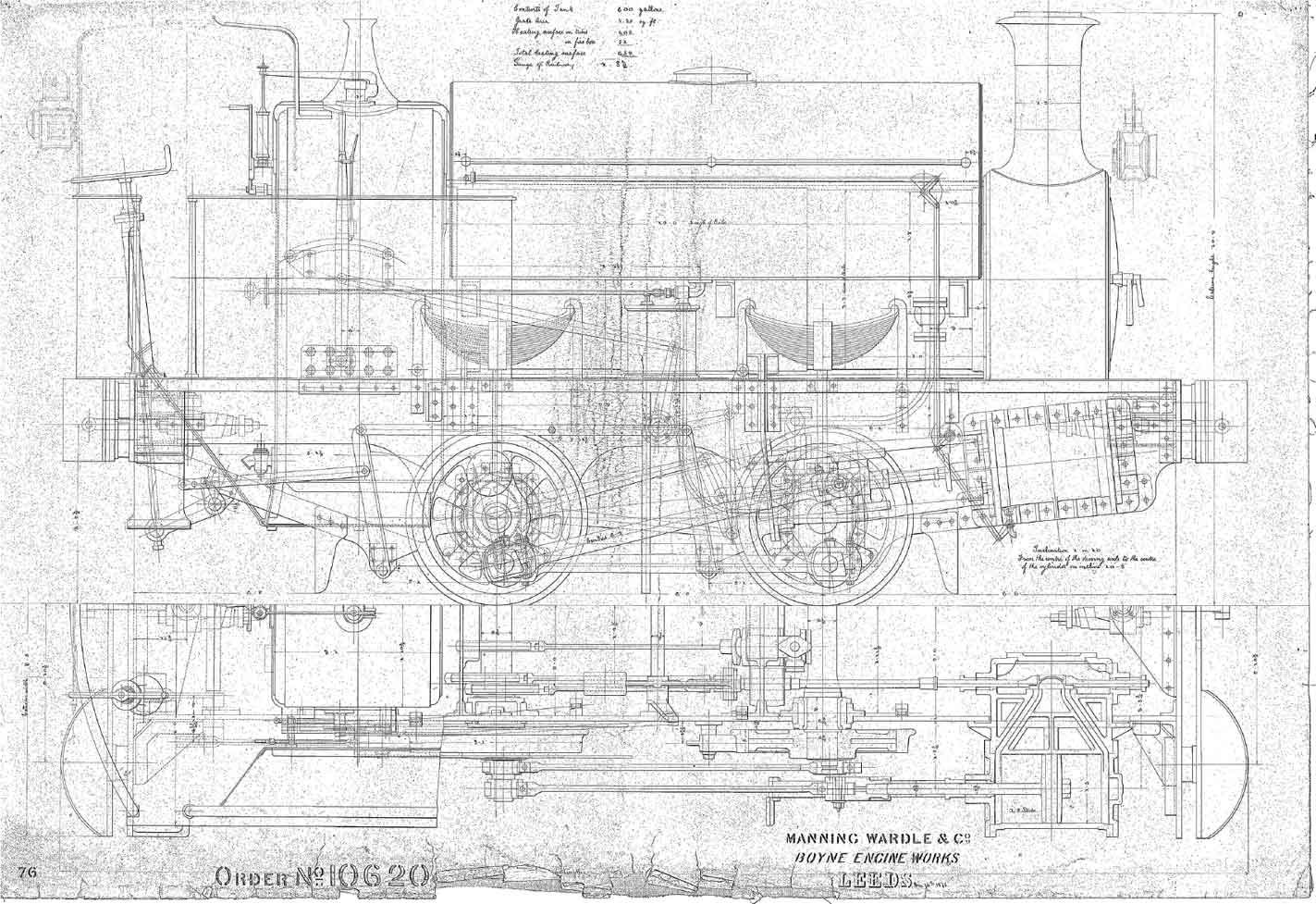

The final piece of the jigsaw – the adaptation of the basic arrangement of Dinorwic to a design that would inspire universal adoption of its principles – fell to Manning Wardle & Co. Ltd and the early experiences with 0-4-0ST Works No. 353 of 1871, later named Lord Raglan, have already been mentioned. The locomotive was a ‘special’ constructed to a specification laid down by the Arsenal and attracted much attention from the engineering press of the time. It had inclined cylinders of 6in diameter with 8in stroke, wheels of 1ft 8in diameter set at a wheelbase of 3ft 3in, most suitable for running on the Woolwich minimum radius of 25 feet, and its cylinders, unlike those of Dinorwic, were inclined at a tangent of 3/26. The design was the world’s first series-produced sub-2ft 6in-gauge-class locomotive to combine full-length outside frames, outside cylinders, direct drive and a proper locomotive boiler. The fitting of an ornate canopy and water feed pump (to back up the injector) were characteristic of many of the company’s products. It is not certain when the dual-gauge bufferbeams and drawhooks initially fitted to Lord Raglan were removed and the mainframes modified, but it may be that this was done in two stages, with the original bufferbeams and upper frame extensions going by January 1873 and mainframe modification occurring at a later date.

In 1873 the next two Manning Wardles arrived, Victoria, Works No. 477, and Albert Edward, Works No. 482. The former of these two locomotives established the true Woolwich variant of the Manning Wardle 6 x 8 narrow-gauge 0-4-0ST that incorporated the modifications of a footplate with a long dropped portion, chamfered mainframes, full-width single composite iron and timber buffers and combined bevel-geared handbrake and reverser pedestals attached to the firebox wrapper. In all a further ten locomotives built by Manning Wardle to similar specification were supplied to the Arsenal up until 1889. The maker’s details relating to all class members as supplied are reproduced in Appendix VII, while the name changes resulting from the 1891 unification of the Arsenal’s railway system are shown in Appendix IX. Arquebus (Works No. 1130 of 1889) was the last of the thirteen, and Manning’s Engine Book records that Arquebus was a ‘special’. Although generally similar to No. 612 of 1876, variations included a special canopy with weather screens back and front, Beck’s patent whistle fitted on top of the canopy, a brass chimney cap, no handrail on the saddle tank and a spark arrester in the smokebox. As can be seen from Appendix VII, from Works No. 555 onwards, the makers recorded the specific department of the Arsenal to which each engine was supplied. During the 1870s and early 1880s, the Manning Wardle locomotives were the mainstay of operations all over the 18in-gauge system, and a photograph published in The Navy and Army Illustrated in 1899 and reproduced here even shows Arquebus on a specially-posed passenger working. By this stage, however, as was recorded a year earlier in Narrow Gauge Railways – Two Feet and Under, the arrival of larger and more powerful locomotives had resulted in the class largely being confined to operation within the tight limits of the shop areas, although their usefulness was far from over. Although the date of their phasing out by the makers on the Woolwich-pattern 18in-gauge Manning Wardle locomotives cannot be ascertained from surviving records, it is known that the earlier class members were fitted with a feedwater preheater (supplied with steam taken from the firebox wrapper steam space). This clearly indicates that the injector was originally intended as a back-up feature for use when the locomotive was stationary, with reliance being placed upon the feedpump when the locomotive was in motion. With the increasing reliability of injectors from the mid-1870s and the superseding of the early Giffard pattern, it was felt by the makers that customers would make more use of the injector while the locomotive was in motion, hence the preheater pipes were soon dispensed with. As will be seen later, the last standard-gauge Manning Wardle supplied to the Arsenal with a Giffard injector was built in 1878 as Works No. 676, although photographic evidence and the lack of reference to the matter in the maker’s records until locomotive No. 986 suggests that the Giffard injector was used for the 18in-gauge locomotives up to and including No. 939.

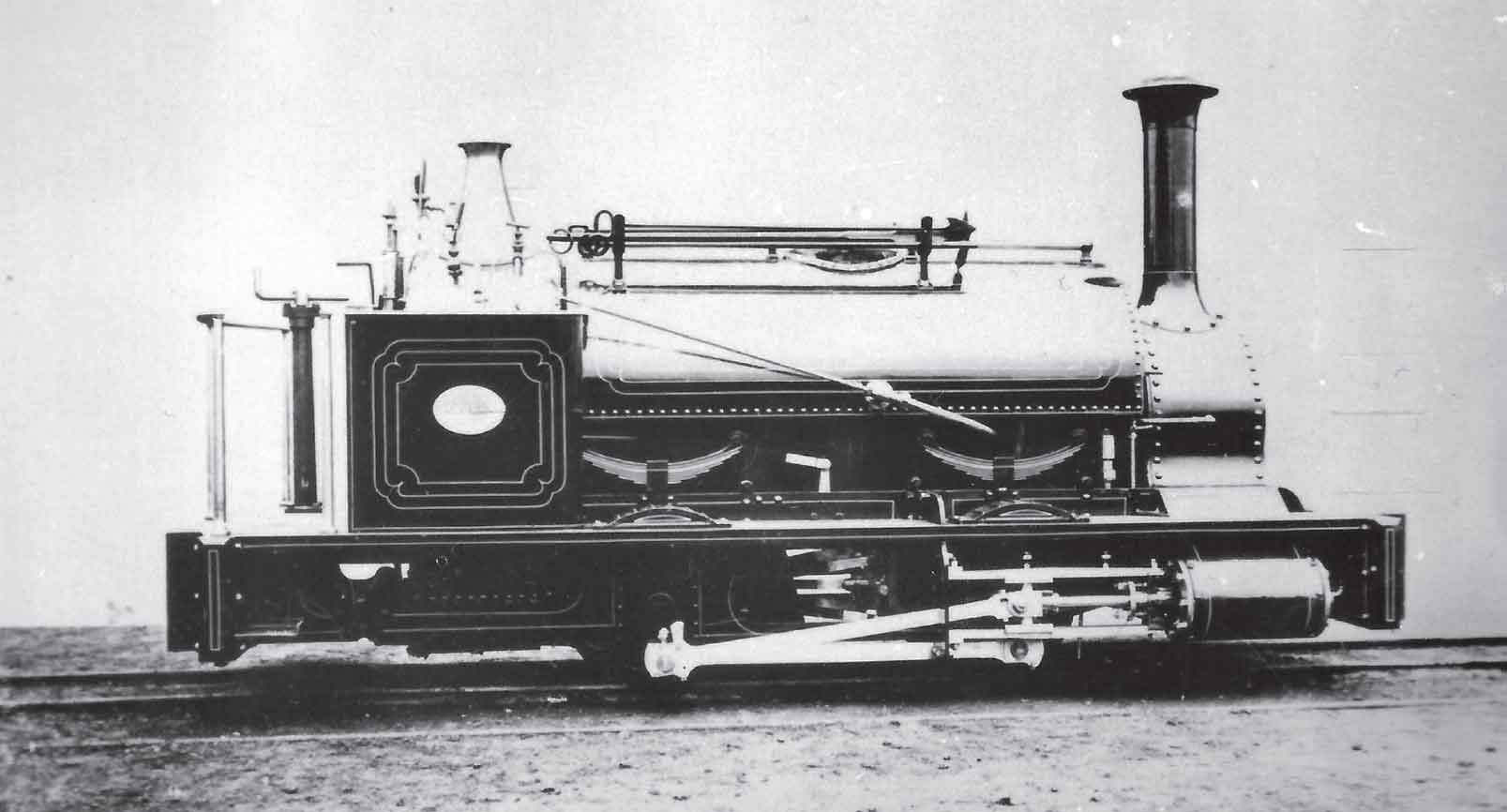

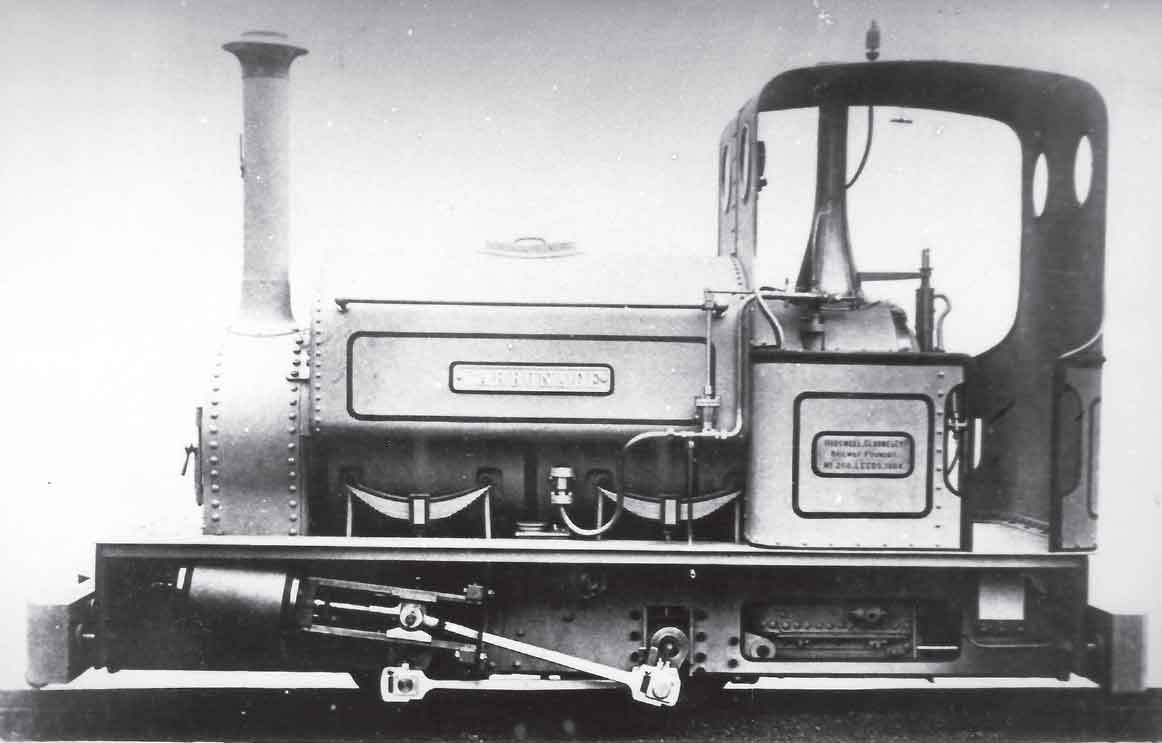

Enter the Leeds influence: following on from the successful production of specialized small standard-gauge tank locomotives for use by contractors and collieries by the Leeds manufacturer E.B. Wilson & Co. during the 1850s and the company’s demise in 1858, similar locomotives were built initially by Manning Wardle, joined shortly afterwards by Hunslet Engine Co. and Hudswell Clarke. The common thread running through most of these designs was the classic ‘Leeds pattern’ domeless boiler with raised firebox wrapper which appeared in rough sketch form in David Joy’s diaries and on Wilson products from around 1850 onwards. Another common feature in use by the early 1860s was the provision of one feedpump and one injector. The standard-gauge locomotives were, of course, fitted with inside mainframes. Following on from Manning Wardle’s unsuccessful tender for the contract to build the Ffestiniog Railway’s first locomotives and this company resorting to the use of non-continuous mainframes for the Ffestiniog & Blaenau Railway’s 2ft-gauge 0-4-2STs in 1868 (in order to obtain a decent size firebox), rival concern Hunslet Engine Co. adopted another approach in the production of its first sub-2ft 6in-gauge locomotive. This works photograph shows the right-hand side of Hunslet Engine Co. Works No. 51 of 1870 Dinorwic, the 1ft 10.75in-gauge 0-4-0ST supplied for use on the Dinorwic slate quarries’ ‘Village Tramway’. The Leeds pattern boiler was very much in evidence, albeit allied to a semi-circular profile water tank, which was used rather less often on early Manning Wardle and Hunslet locomotives than the flat-sided pattern. The combination of an axle-driven feedpump and a single injector, customary on the maker’s standard-gauge 0-4-0STs of the period, was also present, as were the outside cylinders although these were horizontal rather than inclined. In order to accommodate the relatively wide firebox wrapper, it was decided to revert to the full-length outside frames of the Boulton locomotives, but this time of more substantial construction and fitted to a locomotive utilizing direct drive rather than gearing. Despite a respectable working life of over forty-five years (much of which was spent within the quarries themselves after the engine had been displaced from the Village Tramway), Dinorwic’s design was duplicated only once. Although, as mentioned in the text, the slim-gauge locomotive had finally ‘grown up’, Dinorwic’s design effectively fell between two stools when assessed against customer requirements of the early 1870s, lacking the low axle loading of the specialist long wheelbase ‘Fell’ types, or the compactness (particularly of wheelbase) required for many quarry and factory applications where tight curves abounded. (Maker’s photograph)

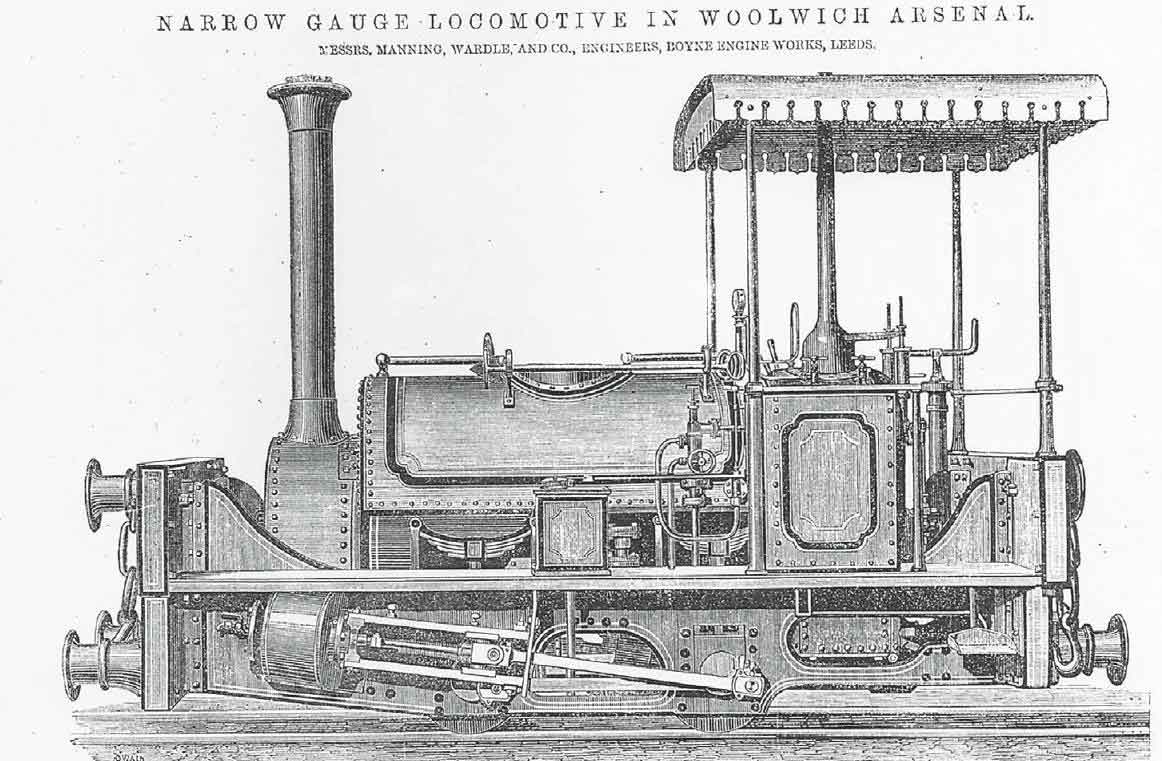

Lord Raglan, the first railway locomotive supplied to the Royal Arsenal, is illustrated in this engraving. As mentioned in the text, the engine was the maker’s Works No. 353 of 1871 and it remained in use on the Royal Arsenal Railways system until withdrawn from service and scrapped during the First World War. The maker’s records indicate that the engine’s mainframes were modified at the Arsenal to be standard with the pattern used by its subsequent classmates but it is difficult to see how this could have been accomplished without renewing the side mainframes. The trial run of this locomotive, at Boyne Engine Works in the presence of the Arsenal’s assistant inspector of machinery, Lt. Heneage, was recorded in the ‘Leeds Mercury’ for February 25th 1871. (The Engineer)

The article featuring Lord Raglan in Engineering appeared in 1873 (some time after the engine was featured in The Engineer), and although it used the same source engraving for the side view, the main body of the text concentrated on the fact that the three Manning Wardle products using similar working components that had been completed in the meantime had all been supplied to Chatham. Works Nos 386 of 1871 Trafalgar and 424 of 1872 Busy Bee were constructed for use in the dockyard, while 448 of 1873 Burgoyne was supplied (shortly before the appearance of the article) to the School of Military Engineering. No General Arrangement was ever known to have been produced for Lord Raglan (or, for that matter, Trafalgar), hence Engineering turned to the GA for Busy Bee for inspiration when incorporating a drawing of the type into the feature. This was in turn copied by Vignes, even to the extent of the omission of the rear edge of the angle iron securing the left-hand mainframe to the leading bufferbeam (a mistake originally made in Engineering)! Owing to the ‘Chatham bias’ of the Engineering feature, Vignes appears to have mistakenly assumed that the rectangular ‘short-framed’ variant of the specification (pioneered with Busy Bee and adopted for five of its dockyard sisters plus Burgoyne) was the sole mature form, hence ignoring the ‘Woolwich’ specification that was to appear shortly after the publication of the Engineering feature. (Vignes Etude)

The rear view shows the upper backhead detail and the ornamental canopy more closely associated with the maker’s products for the export market. The other feature most immediately apparent is the unsightly ‘double’ bufferbeam used to enable the engine to handle standard-gauge wagons. (The Engineer)

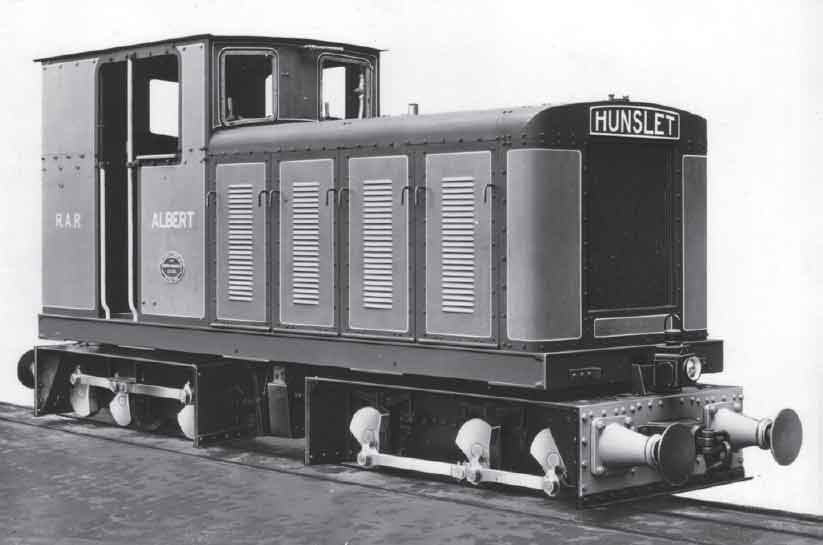

The impact of the acceptance by the railway engineering world in general of the Manning Wardle 6 x 8 0-4-0STs cannot be overstated. The class was featured in both The Engineer and Engineering (in 1871 and 1873 respectively), it was also featured in the influential Vignes Etude of 1878 and in 1873 a Chatham-pattern class member was purchased for evaluation by the Royal Engineers at Chatham’s School of Military Engineering, partly on the grounds of the type’s anticipated widespread adoption. In addition to its basic specification being adapted (in long wheelbase form) by the makers for use on locomotives of a type promoted by John Barraclough Fell, both at home and for export, its most immediate impact was on the evolution, from 1879 onwards, of the mainstream ‘Quarry Hunslets’ and their close relatives. Soon the direct drive, full-length outside frame, outside cylinder, locomotive pattern boiler combination was being adopted for locomotives of 2ft 6in gauge and under by many builders, both inside and outside the City of Leeds, and would remain the order of the day until the end of steam locomotive construction for the 18in-gauge system at the Royal Arsenal. Apart from the Quarry Hunslets, celebrated British-built examples of the basic genre included Beddegelert of the North Wales Narrow Gauge Railway; Russell of the Portmadoc, Beddegelert & South Snowdon; the Lynton & Barnstaple and Vale of Rheidol 2-6-2T classes; the Leek & Manifold 2-6-4Ts; all except the first of the Campbeltown & Machrihanish locomotives; and many examples for non-passenger lines such as Jack and Mary for the Cliffe Hill Granite Co. Narrow-gauge locomotives of this basic type were also constructed by overseas builders in places as diverse as France, Germany, Australia and, in bar-framed form, the USA. In its home country, the last locomotive of the basic type constructed for non-tourist use was Hunslet Works No. 3902 of 1971, an updated version of the Kerr, Stuart Brazil-class 0-4-2ST for export to Indonesia. This historic locomotive has since been returned to the United Kingdom for preservation and is now resident at Statfold Barn near Tamworth, Staffs.

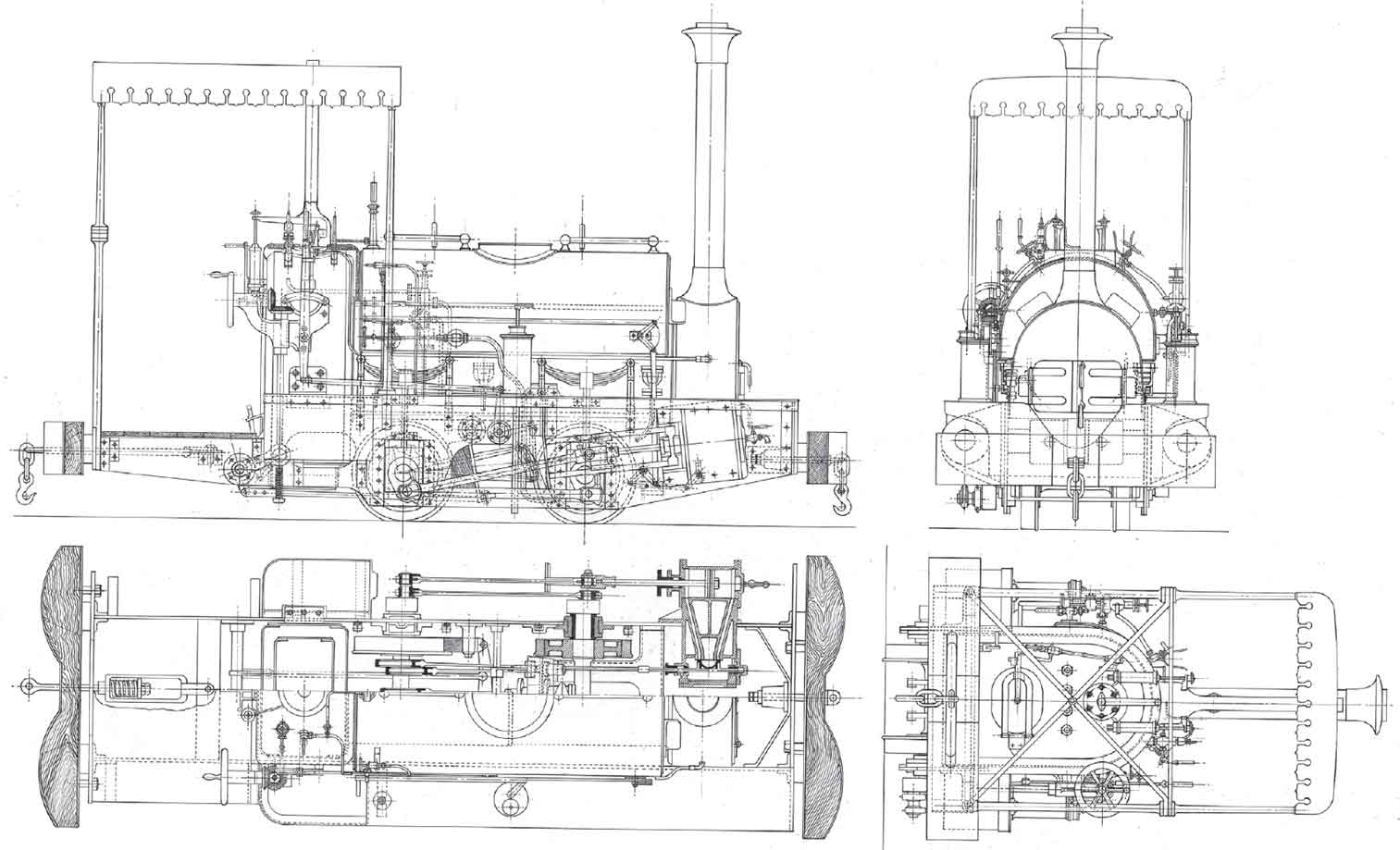

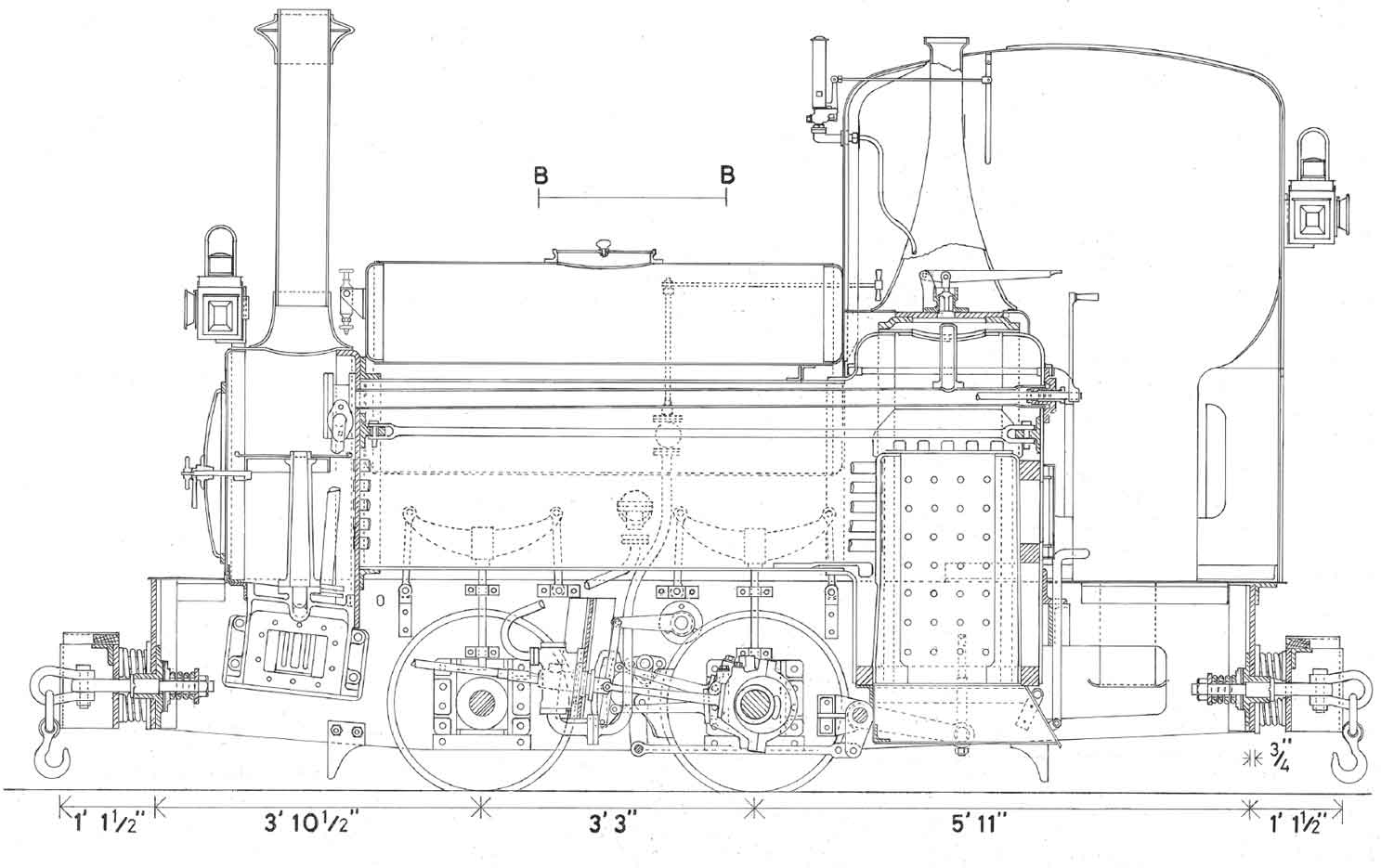

The early mature form of the ‘Woolwich’ specification of Manning Wardle 6in x 8in 0-4-0ST appeared as Works No. 477 Victoria in November 1873 and, as with Busy Bee for Chatham Dockyard, a General Arrangement was prepared. At this stage of development, the fully-fringed canopy is still evident, as is the open footplate with wooden flooring, the exposed bevel-geared brake control/reverser assembly and pipework for the pressure gauge, tank preheater, blower and feedpump (both starting and main water pipes) found on parts of the Arsenal’s railway system are very much in evidence. A Giffard injector would have been fitted on the left hand side and this is shown in dotted outlines. Victoria was renamed Boxer, presumably in 1901, was rebuilt within the Arsenal in 1911 and remained in RAR service until 1916. (The late R. Smithers)

The early mature 18in-gauge Manning Wardle specification is exemplified by this works’ photograph of No. 613 of 1876. As with Lord Raglan, the nameplate is not shown, but the locomotive was named Shrapnel. (Maker’s photograph)

The later mature form of the Royal Arsenal 18in-gauge Manning Wardles is illustrated by this drawing of 1887-built Torpedo. The simplified cab structure, cab footplate of uniform width with the leading portion of the locomotive and Manning Wardle-pattern injector are much in evidence. (The late R. Smithers)

The final ‘as built’ form of the Woolwich narrow-gauge Manning Wardles is shown in this view of Arquebus (Manning Wardle Works No. 1130 of 1889). By this stage of development, all canopy fringes had been dispensed with (facilitating the fitting of a rain strip from new), and the fitting of waist sheets and spectacle plates had produced something approaching an enclosed cab. The footplate layout changed little from the second locomotive of the series (No. 477 of 1877), save for widening at the rear end (so as to be flush with the coke boxes), dispensing with the wooden flooring, incorporating later pattern Dewrance’s water gauges and mounting a Beck’s patent whistle on the cab roof. Other detail differences would have included the substitution of a Manning Wardle injector for the earlier Giffard pattern (as with Torpedo) and dispensing with the tank handrails. Roscoe cylinder lubricators are also very much in evidence, mounted on the leading parts of the tank sides. (Maker’s photograph)

The experimental work of Lieutenant Colonel F.E. Beaumont concerning the use of compressed air as an alternative source of motive power to steam has already been considered in greater detail and there is nothing further that can be added here regarding the prototype 18in-gauge compressed air locomotive of 1877, nor Fox Walker 386 of 1878, save for the fact that neither appears to have enjoyed long operating careers on the Arsenal’s railway system. There is an outside possibility that the Fox Walker locomotive may have seen use on a railway system constructed by the Royal Engineers from 1886 onwards to serve the Brennan Torpedo Installation at Fort Camden in County Cork (now in the Republic of Ireland), but surviving evidence to prove or disprove this assertion is not forthcoming at the time of writing.

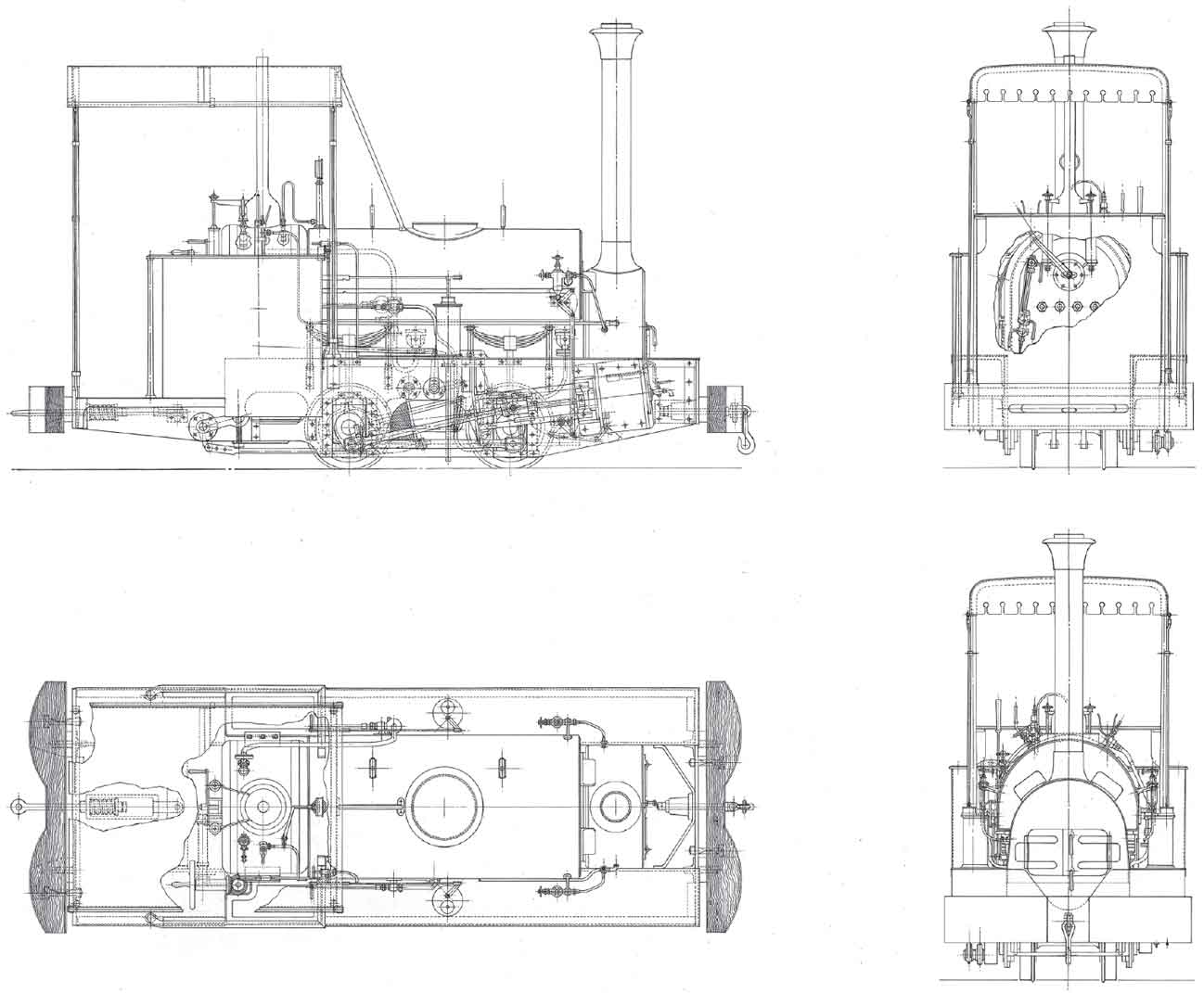

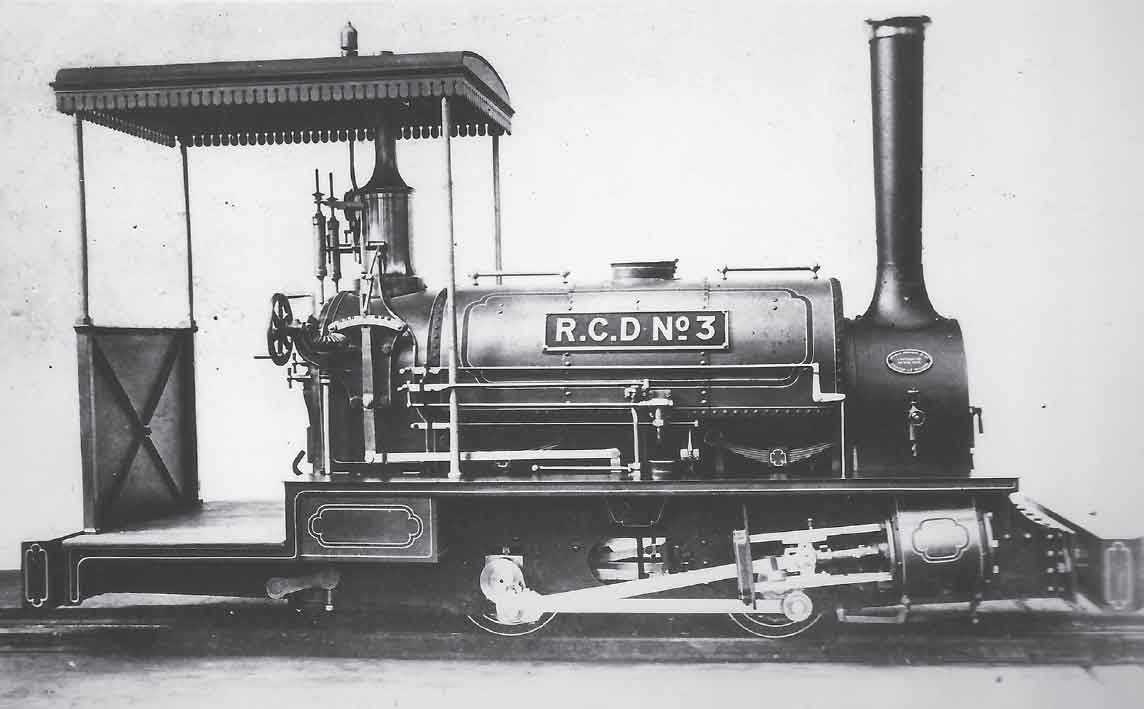

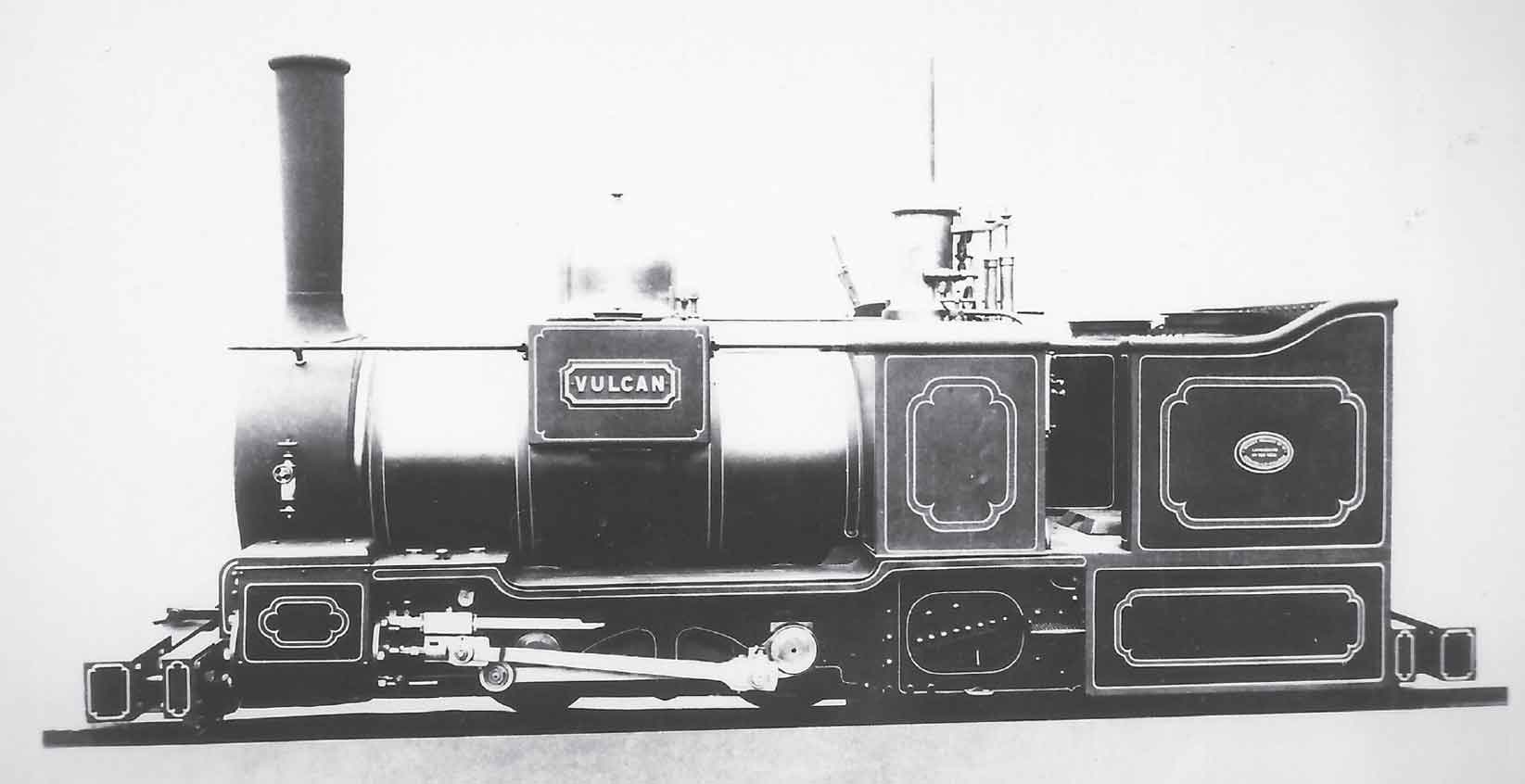

The first non-Manning Wardle 18in-gauge steam locomotive supplied for mainstream use on the Arsenal’s railway system was allocated to the Royal Carriage Department. This was Vulcan Foundry Ltd Works No. 838 of 1878, RCD No. 3 (renamed Iron Duke following the 1891 unification). It seems likely that the main reason for allocating the contract for construction of the locomotive to the Newton-le-Willows maker was a political one, namely the wish not to give one builder a monopoly on the supply of locomotives for military and military support services. It cannot now be ascertained whether Vulcan Foundry’s experience in supplying the gun haulage locomotives over thirty years before played any part in their choice as a supplier to the Arsenal. Be that as it may, Iron Duke bore a strong resemblance to its Leeds forebears in its general appearance, although its wheelbase was longer by 6 inches, its wheel diameter was increased by an inch and the cylinder dimensions were 7in x 9in. As with the Manning Wardles, Iron Duke was fitted with an axle-driven feedpump and a single injector, an arrangement that was to remain standard for all new 18in-gauge steam locomotives designed specifically for use at the Arsenal until 1915. This latter set of dimensions is interesting in one important respect, namely that 7in x 9in was the next stock size of cylinder used by Manning Wardle after 6in x 8 in. The earliest recorded use of this cylinder size by the Leeds maker was on two inside-framed 2ft 6in-gauge 0-4-0STs in 1883 (Works Nos 878–9) that were constructed in a similar general style to the Woolwich and Chatham-class locomotives (two later Manning Wardle products probably used the 7 x 9 cylinder castings bored out to slightly smaller diameters, these being 2ft-gauge 0-4-0ST Works No. 1371 of 1897 Colonel Wilson and 3ft 10in-gauge 0-4-2ST Works No. 1660 of 1905 Lamplough Wickman, the latter possessing a rounded water tank of similar shape to those used on the 18in-gauge locomotives). The question therefore arises as to whether Manning Wardle tendered a 7in x 9in proposal for the locomotive that became RCD No. 3, only to be defeated by the considerations detailed above (possibly with the cylinder patterns being used in the manufacture of Nos 878–9). Given the zeal of the Leeds manufacturer in pursuing orders for locomotives for use at Woolwich and Chatham (see also the company’s role in the story of the Hornsby locomotives discussed later), evidence for the plausibility of such a design proposal is strong, although its existence is unlikely ever to be proved from surviving evidence. Given the enlarged dimensions and particularly the longer wheelbase of Iron Duke when compared with the Manning Wardle locomotives, there is strong evidence to suggest that the Vulcan Foundry product was intended for use on the then embryonic 18in network linking the various shops rather than in the shop areas themselves. It may even be that the Iron Duke hauled the first 18in-gauge passenger vehicles, although this cannot now be known for certain.

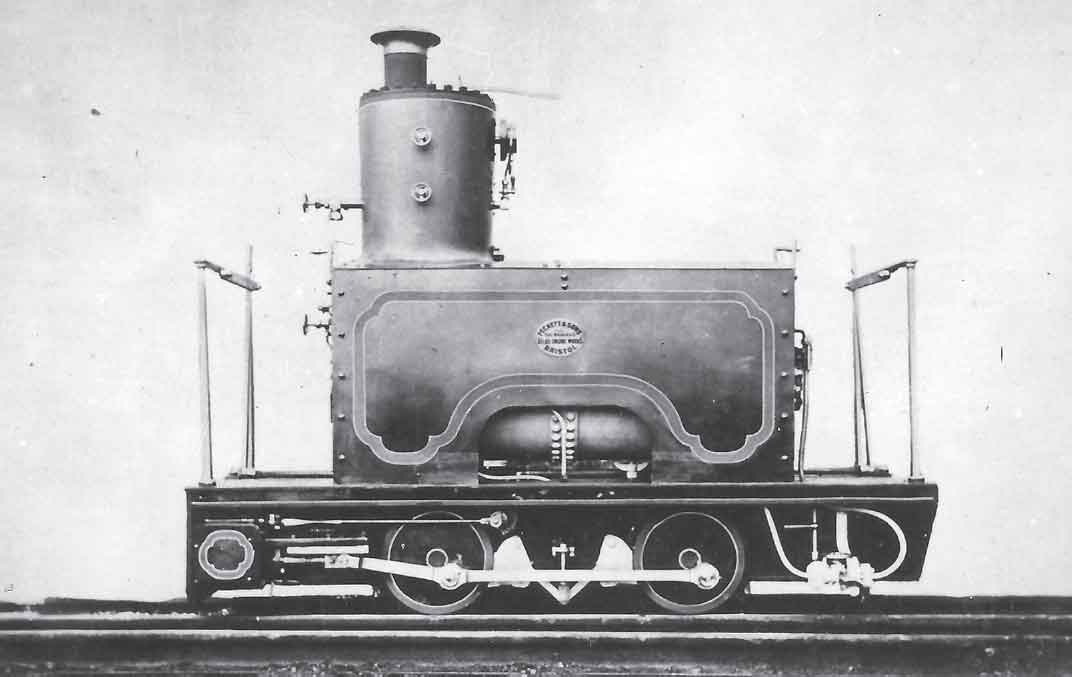

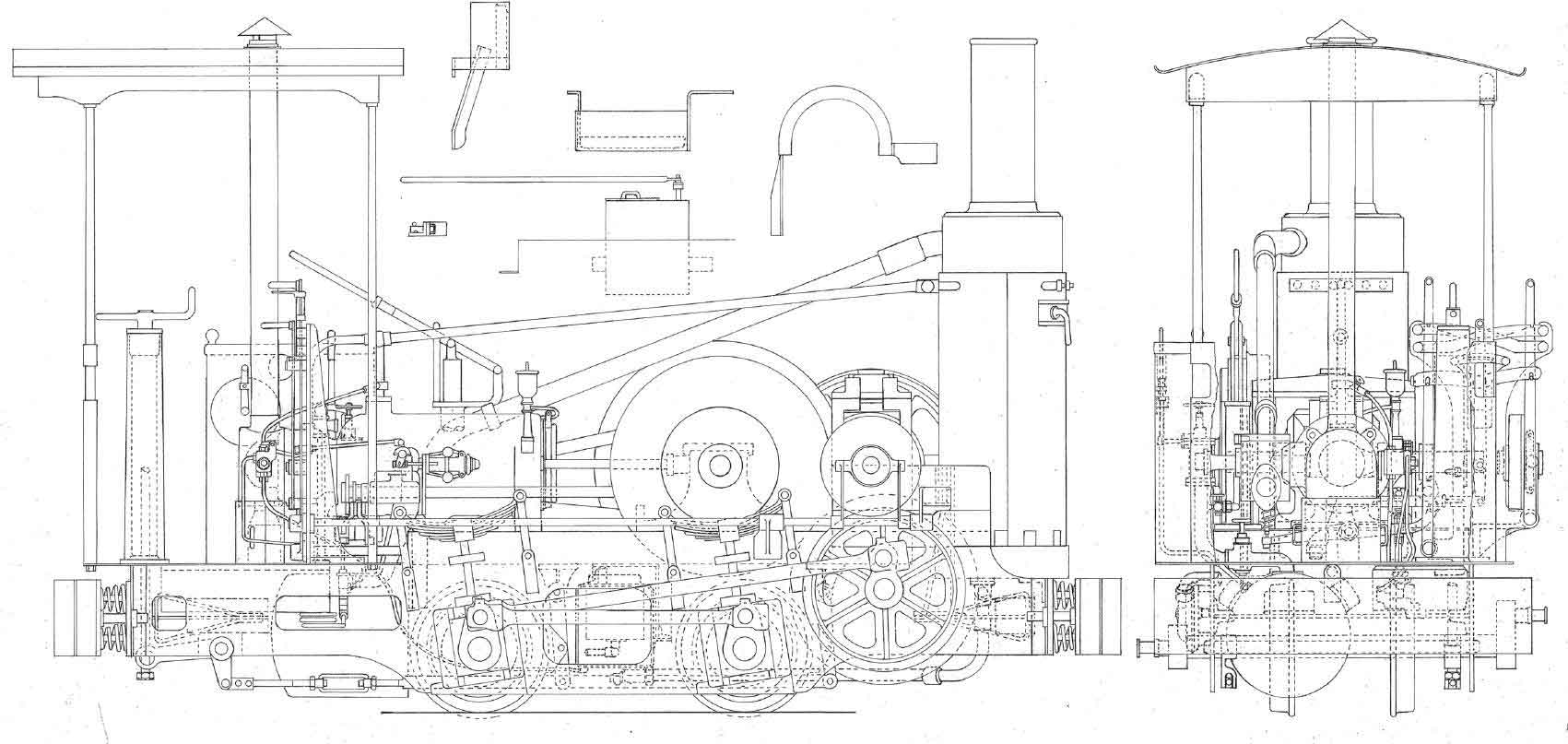

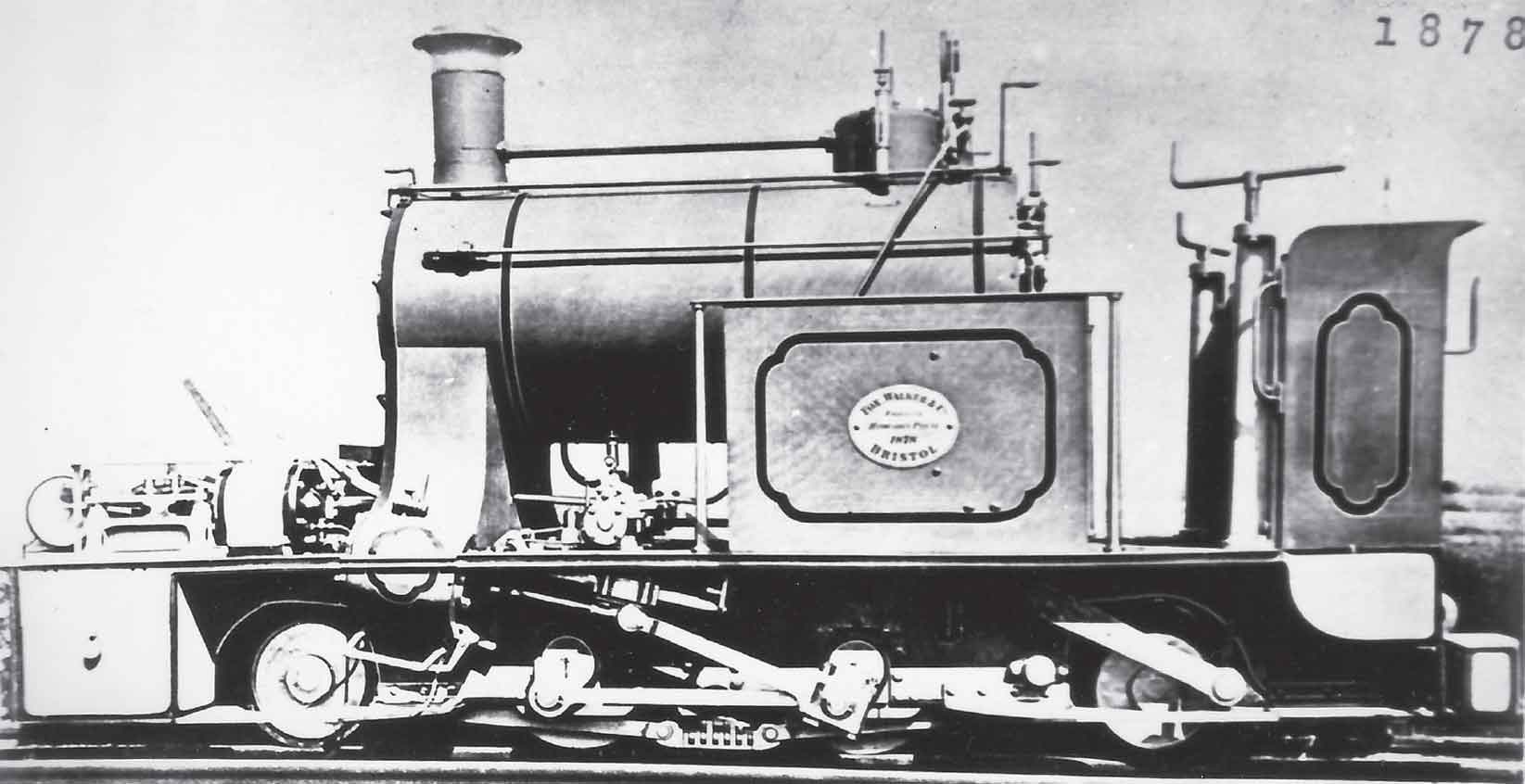

For reasons that have never been fully explained this 0-4-0WT was supplied by Fox, Walker & Co. to the War Department in 1878 as the Makers’ class WATE for use within the Arsenal. Constructed to the same design as Billy (rebuilt) and Dickie of Crewe Works fame, this locomotive (which could be driven from either end) had cylinders of only 5.5in x 6in, wheels 15in diameter and (probably) a working pressure of only 90psi. It would have been of little practical use for the Arsenal’s traffic requirements although, as suggested in the main text, its building date may have been of significance when one takes into account Lieutenant Colonel Beaumont’s experimental work of the period. The locomotive had certainly been disposed of by the Arsenal before 1898 and in all probability several years prior to this date. (Maker’s photograph)

Although the purchase of Iron Duke had demonstrated that the Arsenal authorities were prepared to seek enlarged locomotives from non-Leeds-based sources, a Leeds-based supplier was resorted to for the next group of designs to be supplied for use at the Arsenal. Before discussing these locomotives in detail, it will be helpful to consider the implications of developments relating to the Manning Wardle 6 x 8 0-4-0STs not constructed for use at Woolwich. In all, there were fifteen such locomotives: six of 18in gauge for use at Chatham Dockyard between 1871 and 1899; the similar example of the same gauge for the School of Military Engineering in 1873 already referred to, all of these having rectangular mainframes; three further 18in-gauge locomotives for Argentina between 1890 and 1924 having chamfered mainframes, with an earlier locomotive of the same gauge for Russia in 1875 believed also to possess the same; a 20in-gauge specimen of the same vintage for a Scottish colliery with only slightly chamfered mainframes; a 2ft-gauge 1874-built example again for colliery usage with pronounced chamfered mainframes; and two further 2ft-gauge examples of 1874 and 1877 about which little is known, save for the fact that the earlier example later turned up as a ‘contractor’s locomotive’ on the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. The importance of this analysis is that a dichotomy opened up at an early stage in the evolution of the Manning Wardle ‘slim gauge’ 0-4-0ST locomotives that was to manifest itself not only at the Royal Arsenal, but also in the sphere of the well-known and largely still extant Quarry Hunslet group of classes built for use in North Wales. The choice of whether to adopt the simplicity and robustness of simple rectangular mainframes or use a configuration chamfered at its leading and/or trailing lower edges was normally determined by considerations of ease of access to areas between the frames, the length of overhang (particularly at the rear end) and the abundance of gradients on the locomotive’s working route. Be that as it may, the next two narrow-gauge locomotives to be delivered to the Arsenal adopted the simple rectangular mainframe configuration, rather in the manner of Manning Wardle Works No. 424 Busy Bee delivered to Chatham Dockyard over a decade earlier.

As evidenced by the previous caption, the Manning Wardle monopoly on the supply of 18in-gauge steam locomotives to the Arsenal was broken in 1878 and, in the field of locomotives intended for ‘mainstream’ traffic within the Arsenal, the first movement in this direction was made by the Vulcan Foundry. RCD No. 3 (later Iron Duke) was Maker’s No. 838 and in many respects followed the Manning Wardle lead in its design. Important differences included the longer wheelbase, the suspension of the expansion link from its functional mid-point (rather than the simpler but less mechanically exact bottom-hung arrangement used on the Manning Wardles), and the front end of the mainframes. The maker’s favoured pattern of brass-capped ‘stovepipe’ chimney was also in evidence. Iron Duke remained in service until authorized for disposal in March 1915, being scrapped shortly afterwards. (Maker’s photograph)

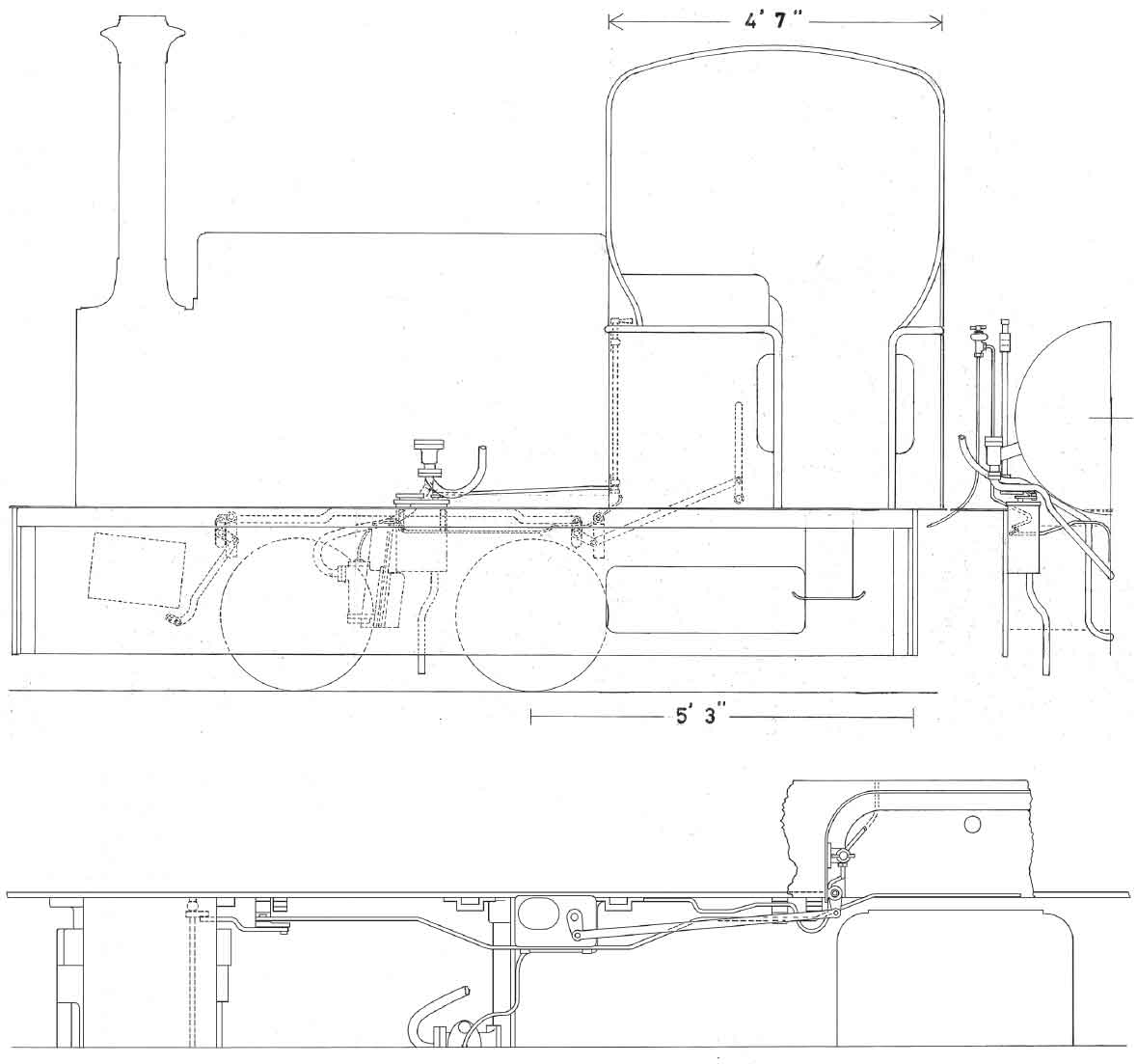

This drawing of Iron Duke as built illustrates the constructional details of the design. The longer coupled wheelbase, when compared with the previous narrow-gauge Arsenal locomotives, would have been a major handicap when negotiating curved track in confined shop areas. Was RCD No. 3 designed as a narrow-gauge ‘mainline’ locomotive, only to be superseded when it was shown possible to construct locomotives with even larger cylinders that retained the 3ft 3in wheelbase used by Lord Raglan? (Author)

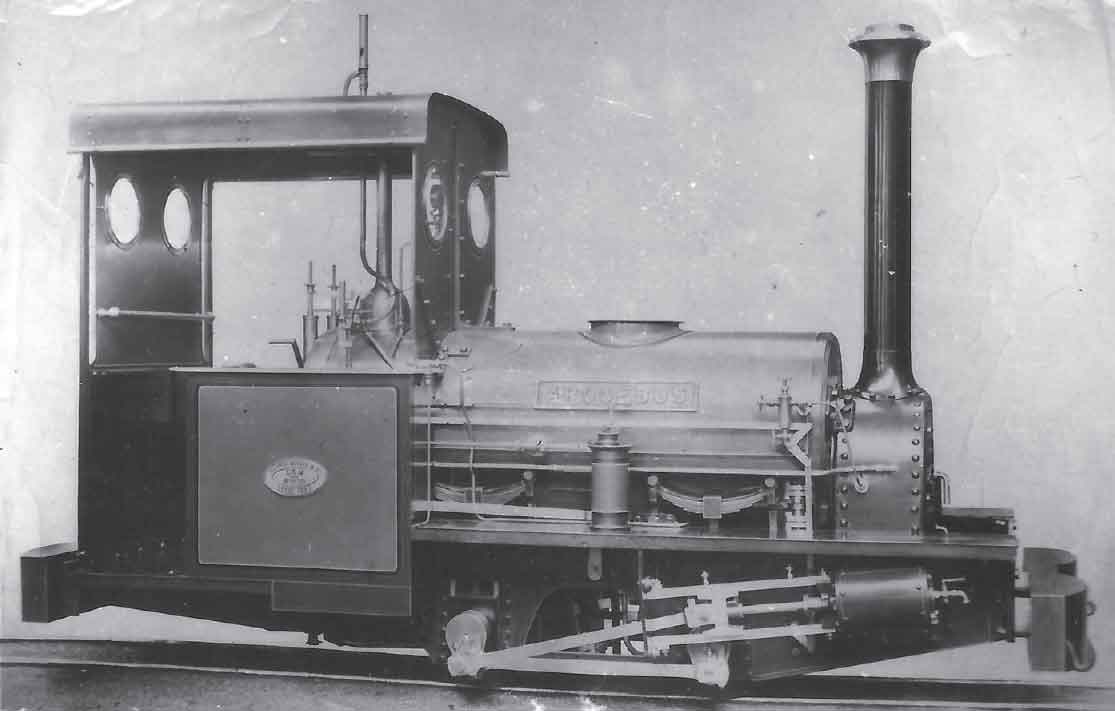

The first Hudswell Clarke 0-4-0STs to see service on the Arsenal’s 18in-gauge system, Carronade and Culverin, were delivered in 1884 respectively as Works Nos 268 and 269. From the mechanical point of view, their design followed the lead set by their Manning Wardle and Vulcan forerunners, while their general appearance was very representative of their maker’s practice. Indeed it set the pattern for several of the company’s other products, including the well-known 2ft-gauge 0-4-2STs Gwen and Joan for the Oxfordshire Ironstone Company. The familiar Hudswell flat-sided saddle tank was present, along with a wrap-over cab roof and a graceful tall chimney. The familiar Leeds-pattern domeless boiler with raised firebox wrapper (accompanied by a curvaceous brass safety valve trumpet) was very much in evidence, as was the water feed arrangement consisting of the (at this stage mandatory) single injector supported by an axle-driven feedpump. Carronade and Culverin reverted to using the 3ft 3in wheelbase found on the Manning Wardle locomotives but were altogether more powerful, being fitted with 2ft 1in diameter wheels and 7in x 12in cylinders. The maker’s drawings list survives and reveals the fact that while many of the components for these locomotives were of new design, others were adapted from earlier products; in particular the valve motion was derived from that used on Works No. 167 (a ‘Quasi-Fell’ 2ft-gauge 0-6-0ST constructed for Westbury Iron Co. in 1875).

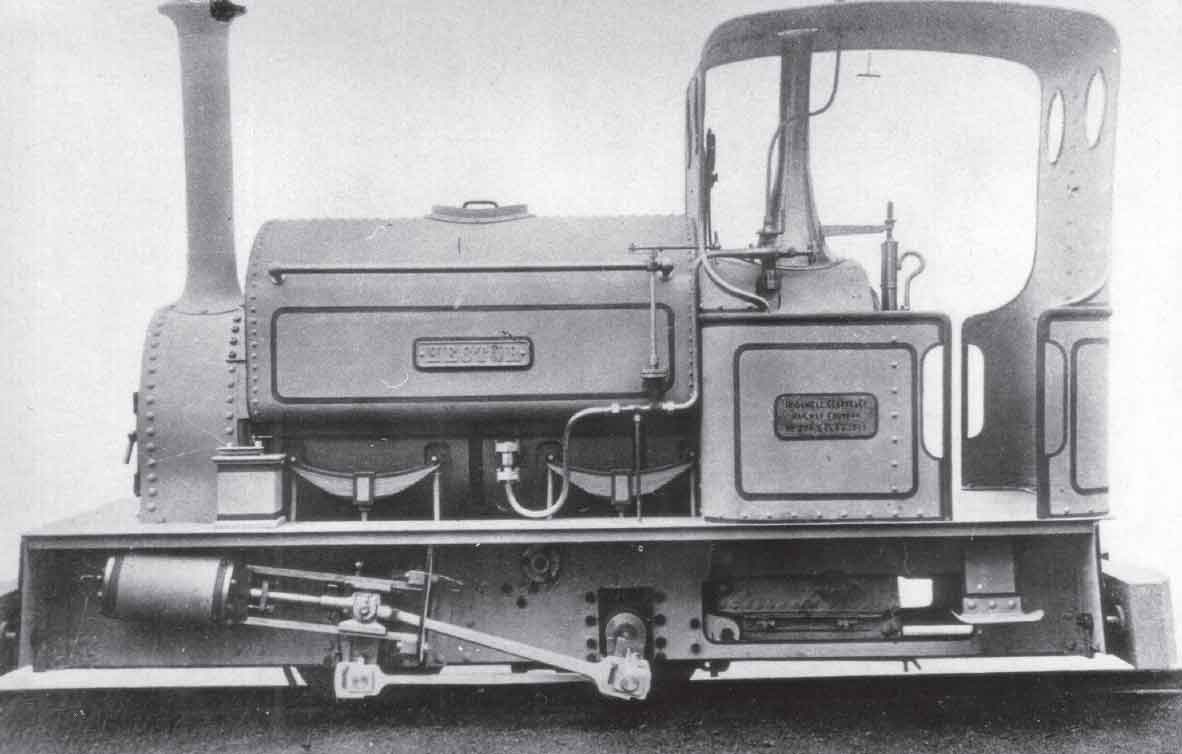

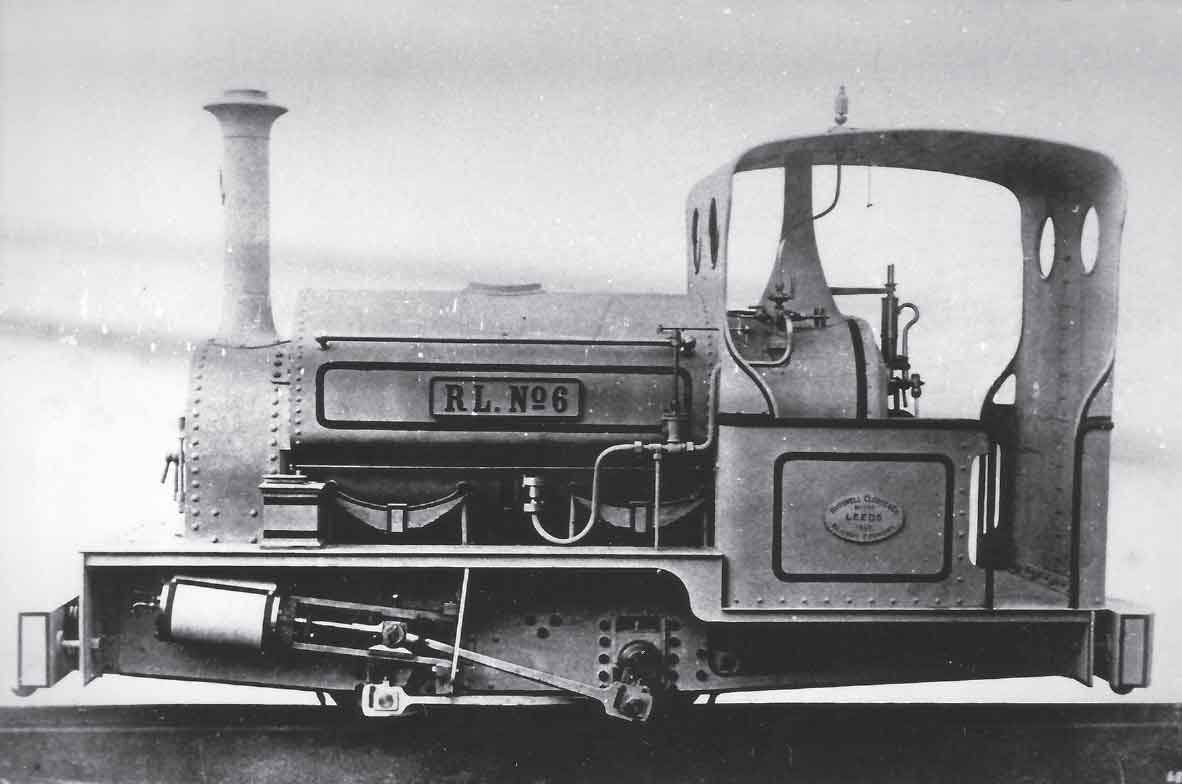

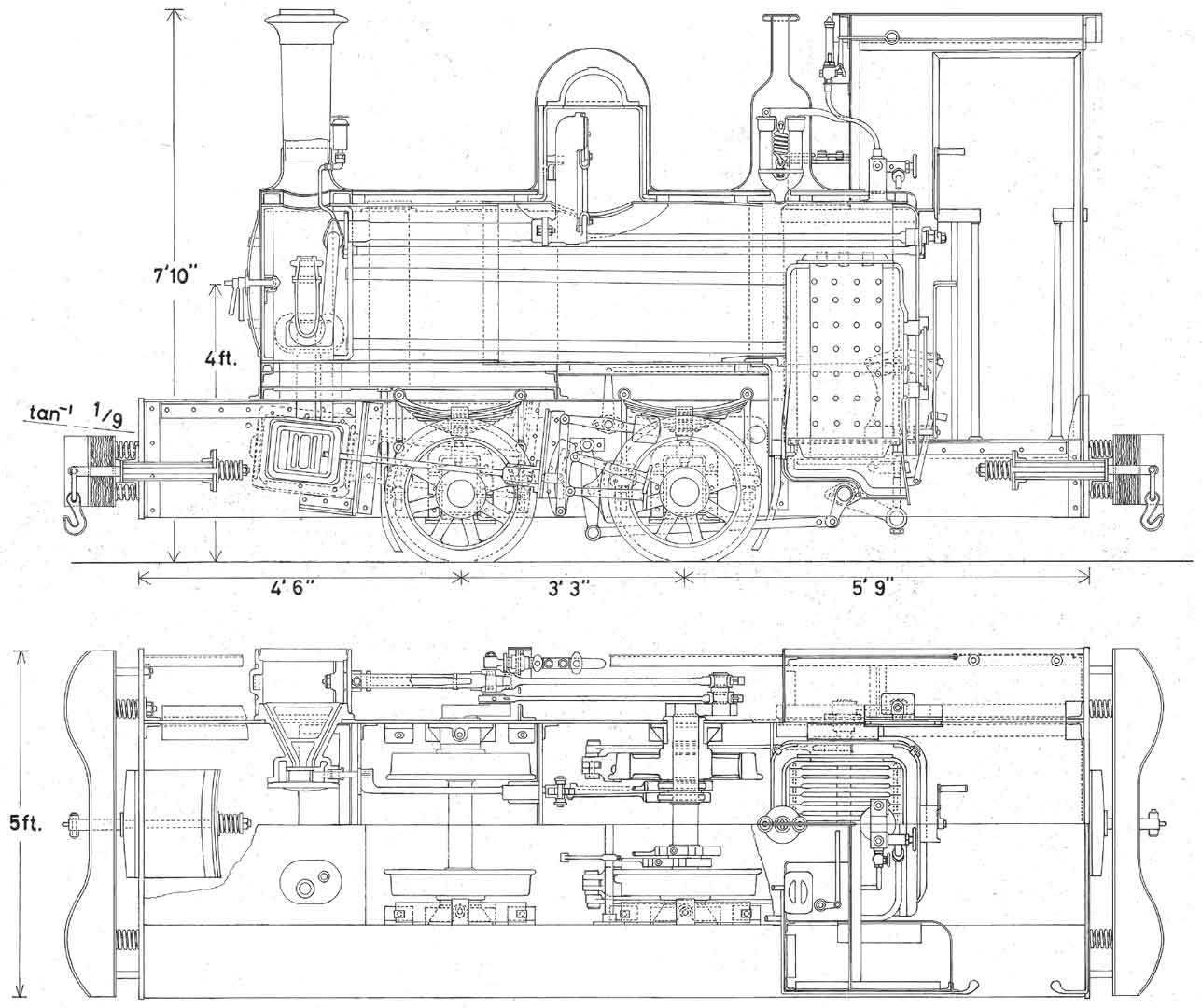

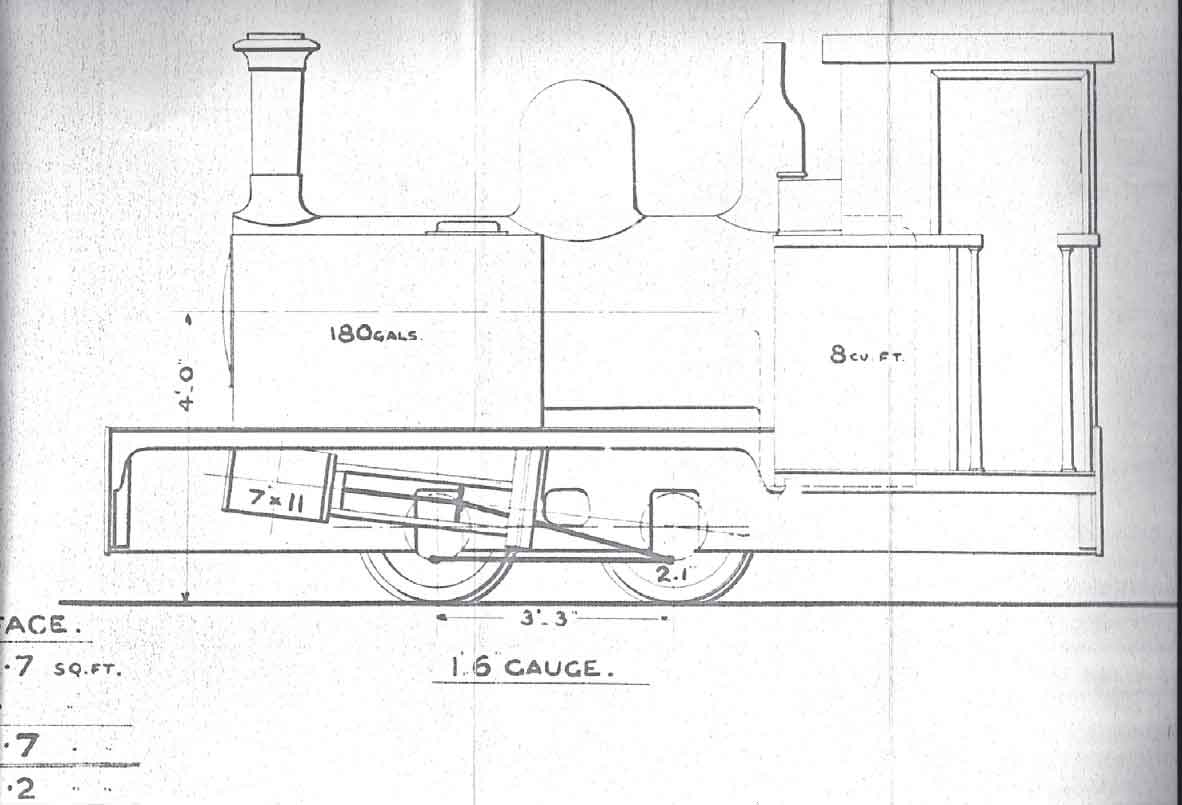

As with the Manning Wardle locomotives, customer requirements dictated design changes and during the next five years, Hudswells supplied seven further locomotives recognizably similar in appearance and overall dimensions but incorporating various improvements and detail changes as the years passed. On the Achilles sub-grouping of four locomotives, Works Nos 273, 274, 280 and 281, the mainframes were redesigned so as to be longer at the rear to accommodate a longer cab and footplate (with associated new design of coke boxes), while four sandboxes of new design (the leading pair mounted above footplate level under the leading edge of the tank and the trailing pair concealed within the cab area) replaced the previous two mounted between the mainframes. The slide valves, link motion, weighshaft and wheels were also of new design. The next development was represented by Works Nos 288 and 345 (respectively Basilisk and Militades), which retained the same thirty-six-tube boiler design (2ft 3in barrel diameter) that had been used on No. 268, but once again the chassis was redesigned, with new drawings being issued for the cylinders, main steam pipe, mainframes, wheelsets, valve motion, weighshaft and suspension. In addition, the alteration of the chassis design had the knock-on effect of necessitating redesign of the cab and coke boxes. The 1887-built RL No. 6 (Works No. 295) was the last nineteenth-century variant of the group to emerge, and the design was further modified to accommodate more severe height restrictions and undulations in track level in the Royal Laboratory area. The lower leading and trailing edges of the mainframes were therefore chamfered, necessitating new frame drawings (along with new drawings for the cab, coke boxes and reverser), the chimney was shortened and the footplate lowered at the trailing end. Significantly, the boiler (and probably the tank) was of new design, although sadly the relevant drawings do not survive to show how the new boiler differed from the previous pattern. The engine’s remaining components were largely the same design as those of Basilisk, although the steam chest cock and associated linkage were also of a revised design. This type was designated by the makers as the Gemini class, although its solitary representative was named Grenade after unification in 1891.

This drawing highlights the detail differences between the first two Woolwich 18in-gauge Hudswells and the second sub-group. The shorter rear overhang, provision of only two sandboxes and the necessary path of the draincock linkage are readily apparent. (Author)

This view shows the first of the Hudswell Clarke 0-4-0ST locomotives for use on the Arsenal’s 18in-gauge system. Works No. 268 of 1884 Carronade was styled very much in the manner of its larger sisters, although the drawgear was, as would have been expected, made to the standard Arsenal specification. As with the preceding Manning Wardle and Vulcan locomotives, the Hudswell narrow-gauge specimens of the nineteenth century either bore names with a military or munitions connection or departmental numbers. The basic design owed much in its inspiration to Hunslet and Manning Wardle narrow-gauge locomotives of the preceding fourteen years (note the domeless boiler with raised firebox, saddle tank, one axle-driven feedpump and one injector, and rectangular mainframes of a pattern seen on Manning Wardle’s Busy Bee for Chatham Dockyard). Despite the fact that only two locomotives of this precise specification were turned out, the entire Hudswell Clarke 7in x 12in group was often given the class name Culverin after the second locomotive, No. 269. Some authorities within the Arsenal preferred the class name Militades after a member of the more prolific second sub-group. In all, four variants of the basic specification were eventually constructed for use within the Arsenal, including the ill-fated final batch of five in 1915. (Maker’s photograph)

The second sub-group of the Hudswell Clarke 7in x 12in specification is illustrated by this photograph of Hector (Works No. 274 of 1885). Hector had a sister engine Achilles (273 of 1885) and they differed from Nos 268–9 mainly due to a longer cab and rear overhang, and the fitting of four sandboxes instead of just two, in this case mounted wholly above footplate level. Once again rectangular mainframes were used, which must have hampered the locomotives’ usage in areas where steep gradients abounded. During the following year, as referred to in the main text, there was a redesign of the basic type (commencing with No. 288 Basilisk) resulting in alterations to the design of much of the area below footplate level. (Maker’s photograph)

Unfortunately, surviving drawings for the main variants of the nineteenth-century RAR 18in-gauge Hudswell 0-4-0ST specification are far from comprehensive, but it has been possible to reconstruct these drawings of Hector from photographs, engravings, known dimensions and drawings of the later 1915 series. (Author)

The ‘oddball’ of the 18in-gauge Hudswell Clarke group is illustrated in this view of No. 295 of 1887 RL No. 6, the last new steam locomotive built for the Royal Laboratory prior to the unification of the Arsenal’s railway system in 1891. The most noticeable apparent differences between this locomotive and those depicted in the previous illustration are the cut-down chimney and safety valve trumpet, dropped rear footplate and cab remodelled to fit its lowered position, although in reality a considerable amount of redesign work was undertaken when compared with Basilisk. The Hudswell locomotives proved their worth at the Arsenal sufficiently for a further five to be constructed to an updated specification in 1915. In the grander scheme of narrow-gauge locomotive evolution, an 0-4-2ST version was built to a gauge of 18.25in in 1892 (Works No. 392) for export to St Petersburg. This was developed during the following year into the maker’s Manaos-class 2ft-gauge 0-4-2ST (initially Works No. 414 for Brazil), while a year after that, the cylinder diameter was increased from 7in to 8in, the ‘mature’ class dimension, on another similar locomotive built for the same Brazilian customer (No. 426 of 1894). This latter locomotive paved the way for Gwen and Joan, referred to in the main text. Today an example of the basic specification (No. 1559 of 1925) survives in the Puffing Billy Railway Museum at Menzies Creek, Victoria, Australia. The Hudswell locomotives for the Royal Arsenal spawned other descendants, most notably in the form of a 2ft-gauge 0-4-0ST design with 8in x 12in cylinders (Nos 517 of 1899 and 570 of 1900) for Vickers, Sons & Maxim Ltd of Sheffield, which were sold for scrap in 1932, and a six-coupled design of the same gauge built for North Eaton Sugar Mill, Queensland, Australia, from 1896 onwards, of which a specimen survives in its adopted country. (Maker’s photograph)

In service, the nineteenth-century Hudswell Clarke subclasses appear to have proved their worth well, as evidenced by comments in Leslie S. Robertson’s work and the fact that five further locomotives were constructed to an updated version of the Basilisk specification in 1915. The contrasting story of these later locomotives will be considered in Chapter Nine. As mentioned previously, the basic Basilisk specification was destined to have a lasting legacy outside the confines of the RAR system: Hudswell Clarke Works No. 392 was constructed to the 0-4-2ST wheel arrangement using the same boiler design and most mechanical component drawings, but with redesigned mainframes, suspension and buffer/drawgear arrangements. The locomotive is believed to have been ultimately destined for Estonia, but its design appears to have been the basis (albeit with a pillar cab) of the 2ft-gauge Manaos-class 0-4-2ST Works No. 414 for Brazil. Subsequent enlargement of the cylinder diameter of this latter class from 7in to 8in not only resulted in the construction of the previously-mentioned Gwen and Joan but also of Works No. 1559 of 1925 for Pleystowe Sugar Mill, Queensland, Australia, a locomotive now preserved at Menzies Creek on the Puffing Billy Railway in Victoria State.

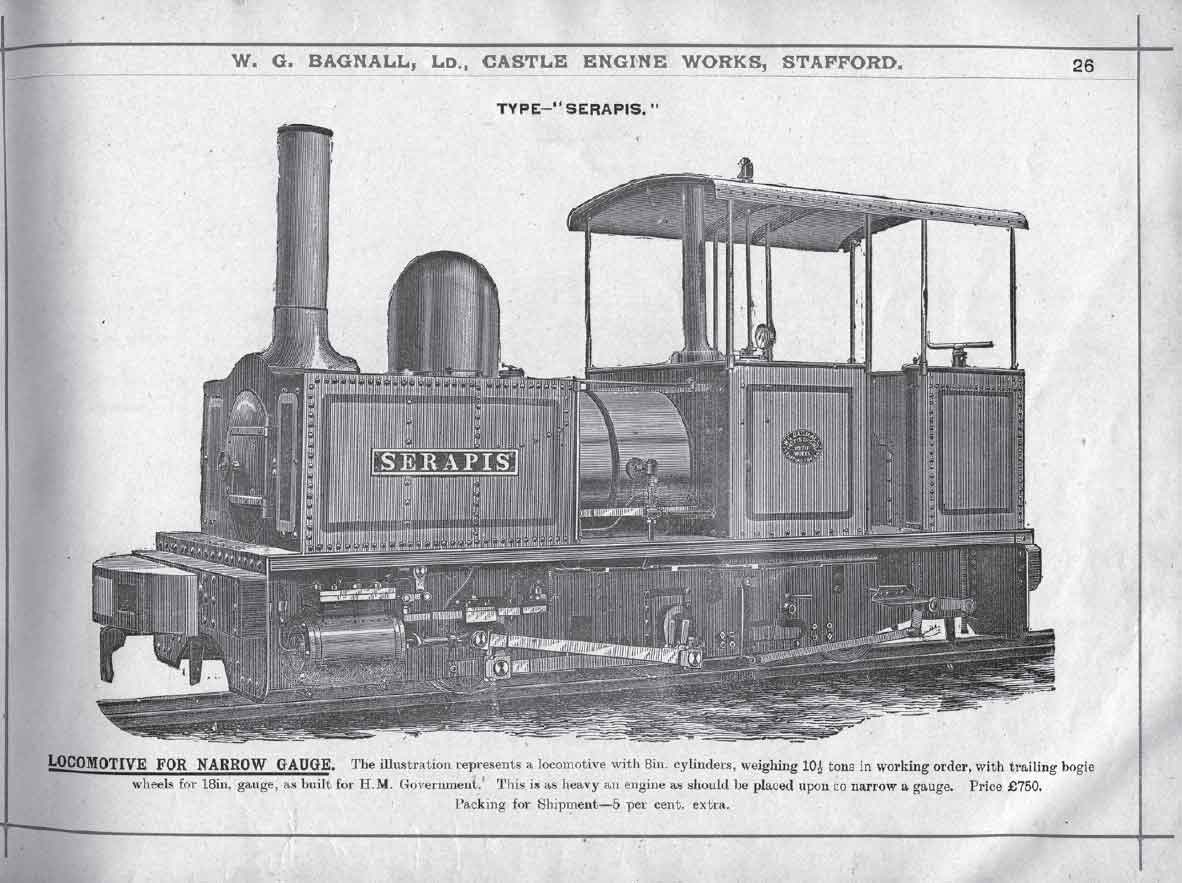

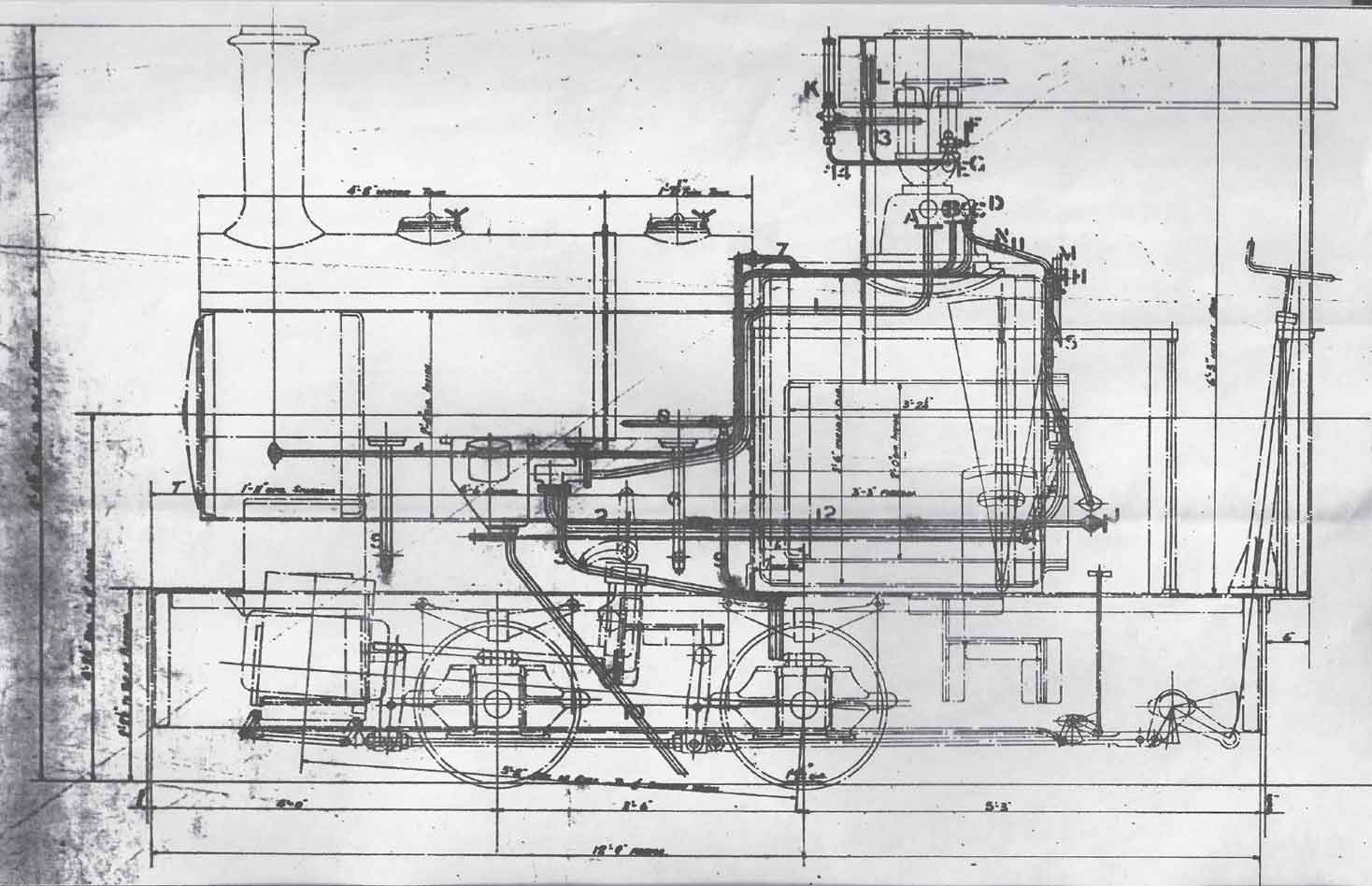

Following an abortive proposal for an 0-4-0 inverted saddle tank locomotive Renown in 1894 for Royal Engineers’ direct usage, Messrs W.G. Bagnall of Stafford produced a modified version of the proposal during the following year as Works No. 1442 for the Royal Arsenal. The locomotive was named Ajax and, as with the Culverin type and its derivatives, 7in x 12in cylinders and 2ft 1in diameter wheels were utilized. The inverted saddle tank configuration had been very much a feature of the Stafford maker’s practice from its foundation in 1876 right up to the turn of the nineteenth century but the design’s disadvantages, such as limited water capacity and restriction of maintenance access to the main steam and exhaust piping, ensured that it fell out of favour with potential customers at a relatively early stage of proceedings. Although the final locomotive constructed for direct or front-line Royal Engineers’ usage, Rameses (Bagnall Works No. 1452 of 1896) was built to the inverted saddle tank configuration (albeit with larger 8in x 12in cylinders and a 3ft 6in wheelbase), the reference in Leslie Robertson’s 1898 work to the Ajax class proved to be optimistic as Ajax was destined to be a ‘lone star’ in the RAR fleet.

In 1894 Messrs Bagnall & Co. came up with this design proposal for a new 0-4-0 inverted saddle tank design with 7in x 12in cylinders for military-related usage. It is not clear whether the design was intended for use on the RAR from the outset or whether it was originally intended for use by the Royal Engineers overseas (the enclosed cab suggests the former whereas the Suakin-pattern drawgear suggests the latter, although Bagnalls may have been unaware of the RAR-pattern drawgear design at this earlier design stage). The apparent lack of provision of sanding gear is immediately apparent, as is the Baguley valve gear, although neither of these features would have been likely to appeal to serious military users. Despite the previous efforts of Major Hogg and Captain Kunhardt in favour of 2ft 6in, 18in gauge was still the narrow-gauge order of the day at this stage for front-line duties and remained so until 1896 when the Royal Engineers decided to discontinue ordering 18in-gauge locomotives for direct military use. The locomotive was a simple short wheelbase outside-cylinder 0-4-0 tank (albeit with horizontal cylinders) indicating that by this stage, and contrary to their endeavours with 2ft 6in-gauge locomotives at the time, the Royal Engineers had come round to the view that trailing trucks were not worth their attendant problems on 18in-gauge locomotives. The last 18in-gauge steam locomotive constructed for Royal Engineers’ front-line use, Rameses (Bagnall Works No. 1452 of 1896), was built to a larger 0-4-0 inverted saddle tank specification incorporating 8in x 12in cylinders, 2ft 1in diameter wheels and a 3ft 6in wheelbase. It was equipped with RAR-pattern drawgear despite being sent to Sudan when new and was destined to end its days there, never seeing service at Woolwich. (Maker’s catalogue)

Above and below: These drawings are intended to show the design features of Ajax as built. They comprise a section and plan view; left-hand elevation; front and rear views; and right-hand details. Certain details pertaining to the working of the leading sanding gear are not shown on the maker’s original documentation and have had to be inferred, although the leading cross tie rod arranged to pass through apertures in the mainframes below footplate level would have been necessary. (Author)

Although the design of the Royal Arsenal Railways’ Ajax was clearly influenced by the Renown proposal, the substitution of inclined cylinders with Stephenson/Howe motion for the proposed arrangement of horizontal cylinders and Baguley valve gear will be noted. Other points to note are the expected substitution of RAR-pattern drawgear for the Suakin pattern proposed for Renown and the configuration of the sandboxes. Rameses (see previous caption) was built with many components standard with a metre gauge inside-framed class (Maker’s Nos 1447–51), but itself followed Ajax in many details, not least in the use of outside frames and link motion, although its ‘cab’ simply consisted of four pillars and a roof, more appropriate for conditions in Sudan. (Maker’s photograph)

Notwithstanding the failure of Beaumont’s earlier experiments with compressed air as a source of motive power on the Arsenal’s railway system, a pressing need was still felt for a safer alternative to the steam locomotive where the presence of dangerous munitions was seen to be a threat to life and limb. The latter part of the nineteenth century had seen the emergence on the commercial scene of a new entrant, namely the internal combustion engine, with its reliance on the burning of hydrocarbon fuel within the cylinder area rather than on a separate supply of externally-generated steam. The elimination of a separate firebox thus offered the possibility of a much reduced fire risk in the vicinity of Danger Buildings, the potential of which was not lost on the Arsenal’s authorities.

The man who was to make the first crucial step in making internal combustion motive power a practicality on the Arsenal’s railway system was born in Halifax, West Yorkshire, on 28 January 1864. Herbert Akroyd Stuart was the son of Glaswegian engineer Charles Stuart who had moved to undertake experimental work at the Bletchley Iron and Tin Plate Works in Buckinghamshire. Educated at St Bartholomew’s Grammar School, Newbury, Herbert is known to have undertaken work as a junior assistant at the City & Guilds of London Technical College, Finsbury, before returning to join his father at Bletchley. After undertaking the work that would pave the way for the development of the locomotives discussed in this volume, Akroyd Stuart (who had incorporated his mother’s maiden name into his own) emigrated to Perth, Western Australia, at the turn of the century where he helped to found Saunders & Stuart Ltd, a company involved in the harnessing of gas power for gold-mining. He died on 19 February 1927, with his remains being repatriated and laid to rest in the cemetery of All Souls Church, Halifax.

A rare survival is this RAR official diagram for Ajax. It amounts to a simple side elevation view and sadly is not dated. It was accompanied by the following dimensions: heating surface, tubes 113.7 sq ft; firebox 18 sq ft; and grate area 3.2 sq ft. It would appear that similar diagrams were made for the other RAR locomotives but sadly they do not appear to have survived. (Courtesy Mike Swift)

Returning to his period of experimental work, Herbert was slightly injured in an accident on a visit to Llanelli, South Wales, in 1885. This involved the spillage of paraffin from a lamp onto molten tin that resulted in vaporization of the oil, subsequently producing a small explosion when the vapour made contact with the lamp. Seeing this as a possible source of motive power, Herbert returned to Bletchley and encouraged his father to undertake initial experimental work on internal combustion engines, which he eventually took over. Starting with a conventional petrol engine of the period, Akroyd Stuart conducted experiments in which the engine was started with petrol and then switched over to safer paraffin when it had warmed up sufficiently. To aid this process, a progressively increasing proportion of the water jacket was withdrawn from the combustion chamber until the paraffin would ignite of its own accord as a consequence of the heat generated by the engine itself. The next stage was to dispense with the primitive spark plug apparatus of the period and move to pre-heating the combustion chamber until the engine could be started by pumping a small quantity of fuel into the chamber. When working, therefore, the engine’s fuel was injected into the combustion chamber (at this stage of development still truly integral with the cylinder) close to the end of the compression stroke on the Otto cycle (as opposed to being pre-mixed with the air as in a conventional petrol engine). The compression-ignition heavy oil engine was thus born as a commercial proposition, and in conjunction with Charles Richard Binney, Akroyd Stuart filed Patent No. 7146 of May 1890. At this juncture, it should be noted that Akroyd Stuart’s work was well in advance of that being carried out by Dr Rudolf Diesel in Germany.

Although a relatively small number of engines were built to this early patent, they suffered from the teething problems of most prototypes. The workmanship in their construction was not thought to be of a particularly high quality and the proportion of heat generated in the combustion chamber (as opposed to that generated by compression) varied greatly according to the load on the engine and its associated fuel consumption. This caused inconsistencies in the pattern of ignition with varying loads and in some cases a tendency towards ‘backfiring’ (pre-ignition). The answer to the latter problem lay in the design of the combustion chamber and the next step in the evolutionary path was to refashion the chamber to the extent that it became a separate vaporizer, connected to the cylinder only by a narrow neck. The fuel oil would therefore now be injected into the vaporizer chamber on the induction stroke, with air being drawn into the cylinder proper on the same stroke. On the compression stroke, the air in the cylinder would be forced into the vaporizer (which for starting purposes had been heated by a lamp as before) for mixing and ignition to take place at the desired point at the end of that stroke. This arrangement resulted in a more consistent pattern of ignition with varying engine loads and effective elimination of the backfiring problem and, in consequence, Patent No. 15994 of October 1890 was filed, again in conjunction with Charles Binney.

The problem of reliable quantity and quality commercial production was solved the following year when the manufacturing rights of the engine were assigned on a royalty basis to agricultural engineers Richard Hornsby & Sons Ltd of Grantham, who, on the advice of their chief engineer, agreed to market and develop the engines. For engines of over 4hp rating, it was found necessary to water-jacket the vaporizer and its neck to reduce the liability of fracture of the latter component in service and to allow for the higher compression ratios associated with the burning of heavier oils. This was provided for under Patent No. 17073 of 1891. During the ensuing years, numerous sundry improvements ensued and, following production of the first Hornsby-built example in 1892, a total of over 32,000 of various types were eventually produced. In addition to the normal stationary applications, road tractors were produced from 1896, along with the first commercially successful application of compression ignition internal combustion power to a railway locomotive, at least in the United Kingdom.

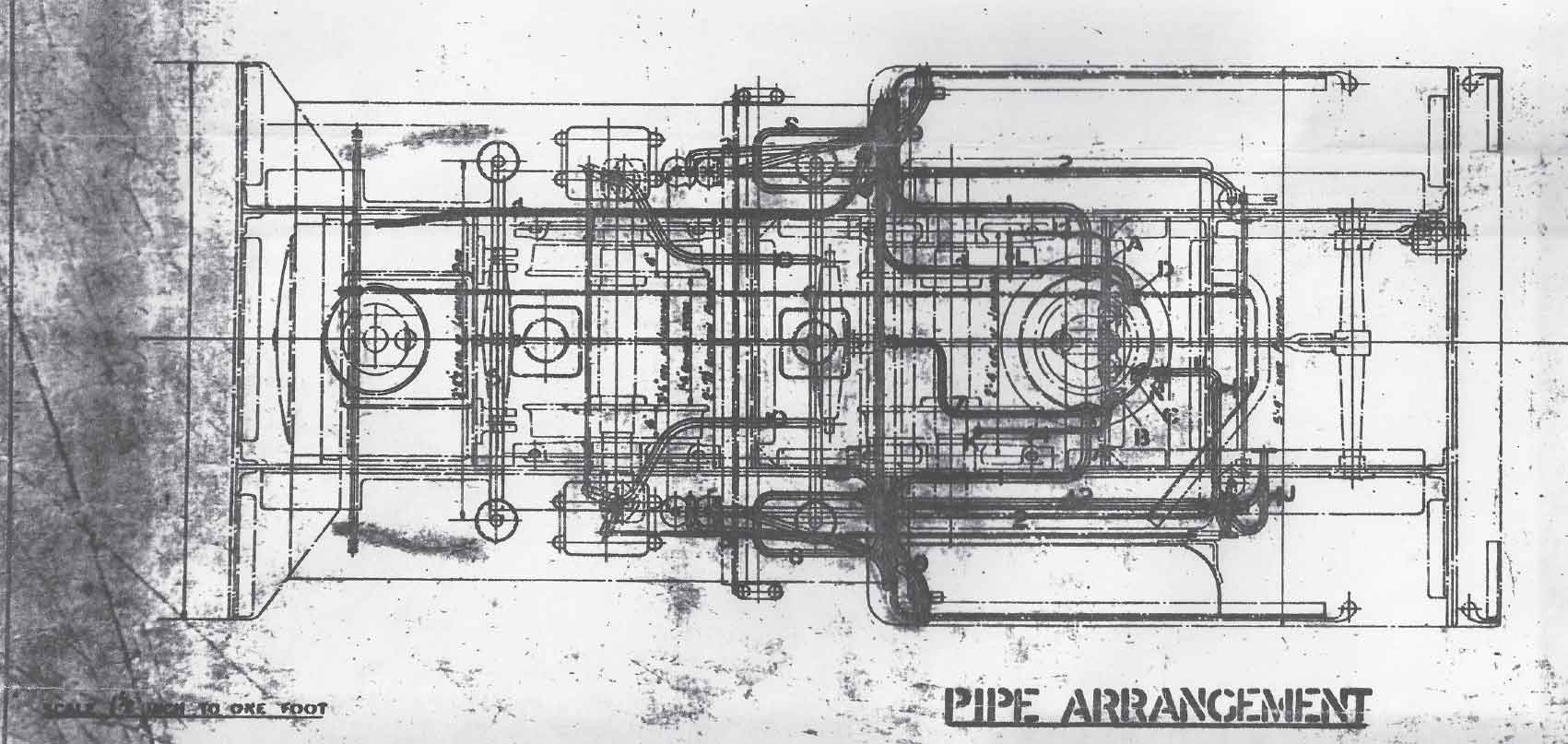

The first of the Hornsby locomotives to be completed for the Royal Arsenal was delivered on 23 July 1896 to the superintendent of building works there and was given the Maker’s No. 1705 and the name Lachesis by the RAR authorities. Although General Arrangement Drawing 14430 showed a locomotive rated at 12.5hp (most of the component drawings for the locomotive were new and numbered in the 14000 series, although the cylinder block and water jacket assembly were constructed to Drawing Number 12591, while sundry other components bore 12000 series drawing numbers), the locomotive that actually emerged possessed an engine with cylinder dimensions of 11in bore x 15in stroke rated at only 9.5hp. Despite this, the maker’s catalogue continued to describe the locomotive as being rated at the higher power output. In order to adapt the basic Hornsby stationary engine for this particular use, the oil tank was no longer situated beneath the engine and its place was taken by the cooling water tank. From this tank the water circulated, via an eccentric driven pump, through water jackets surrounding the cylinder, vaporizer and fuel oil admission chamber and into an upward-inclined pipe that ran forwards above the connecting rod and crankshaft to the cooling tower. This design of cooling arrangement was taken from Patent No. 6122 of 1894 (originally intended for portable agricultural engines), and involved admitting the water via a junction pipe to a series of parallel perforated header pipes inside the top of the tower. From here, the water cascaded down inside the tower into a collecting vessel at the bottom. Immediately above the level of this vessel, perforations in the wall of the tower allowed cool air to be drawn into the tower by the action of the engine’s exhaust, which was admitted through a pipe, via a hole in the wall, to the internal base area of the ‘chimney’ at the top of the tower. A return pipe ran rearwards to the water tank (which contained a filter so that the circulation process could be completed). The fuel oil tank was placed between the locomotive frames behind the rear axle and oil pump (which was actuated from the camshaft), and in order to ventilate this tank, a tall shaft was located within the leading right-hand area of the footplate.

One interesting departure from the manufacturer’s standard stationary engine practice was that the two longitudinal portions of the engine bed of the first four Hornsby locomotives consisted of simple steel girders from which were anchored the locomotive’s brake hangers. One feature found on many Hornsby stationary engines of the period was a fan that was used to assist the burning of the lamp oil. This was actuated by means of a hand crank and intermediate gear, and belt-and-pulley transmission to ‘gear up’ the speed of the fan blades. This feature was incorporated into Lachesis with the fan being located at the rear left-hand side of the locomotive below footplate level and the hand crank above it within the cab at hand level. The gear to which the crank was attached incorporated a semi-enclosed internal rack whose open side engaged with a small pinion, the shaft of which carried the large pulley. This arrangement has caused confusion to many students of the early Hornsby locomotives over the years who have often mistaken the hand crank gear for a warning gong. For stationary engines of 20hp and above, Hornsbys considered it necessary to incorporate what they termed a ‘self-starter’ consisting of a compressed air reservoir that could be primed, via a valve, by a hand pump. Once charged to the required pressure, this vessel’s contents would be used (again via the necessary valve arrangements) to start the engine once the crankshaft had been rotated by hand to the required position. Although the engine used on Lachesis was rated at less than half the threshold deemed necessary by the makers for a self-starter, the locomotive, along with all subsequent early Hornsby oil locomotives, was fitted with this apparatus with the reservoir being mounted between the frames at the rear left-hand side and the hand pump on the same side above footplate level. Although the maker’s photograph does not indicate the presence of any warning device, other photographs taken after the end of the locomotive’s working life show that a whistle was later fitted (along with many other alterations) which was supplied with air when necessary from the reservoir. Lachesis was illustrated in The Engineer of 4 December 1896.

Although experienced in agricultural engineering technology, Hornsbys at this stage had no experience in the production of running gear for railway locomotives and it was no surprise that they turned to an outside contractor for the supply of the ‘rolling chassis’. The identity of this contractor is revealed by close examination of Drawing 14453, which is endorsed with the legend: ‘All these details were bought from Messrs Manning Wardle & Co. See sheets B2437 of Dec 31st 1895 and B2421 of Dec 16th 1895.’ The drawing, which is in two parts, relates to the wheelsets, coupling and jackshaft rods and suspension components. Close examination of this drawing reveals 1ft 8in-diameter coupled wheels that were standard with the narrow-gauge Manning Wardle steam locomotives previously supplied to the Arsenal. It also shows the characteristic screw-adjusted inclined plane split bearings for the crankpins, used by Manning Wardle for some of its products from the 1890s onwards, eliminating the need for cotter pins. The drawing endorsement was barely needed! Owing to the incomplete nature of the surviving documentation, an important question is thus posed: i.e. how far did Manning Wardle’s contribution to the construction of Lachesis extend, given that the Leeds concern did not, unlike with its compressed air locomotives, allocate its contribution a maker’s number, nor is there any reference in surviving maker’s records to any work undertaken for Hornsbys? In order to answer this crucial question, one has to examine the surviving material relating to narrow-gauge Manning Wardle steam locomotives of the late nineteenth century. If one ignores the fact that the horncheeks and axleboxes of Lachesis were inclined slightly backwards (in order to minimize bending stresses on the jackshaft rods caused by vertical displacement of the axles during suspension movements), the shape of the side mainframes on the locomotive closely resembles that found on 2ft 6in-gauge Manning Wardle 0-4-0T No. 1615 of 1903, the last of three similar such locomotives supplied over a period of seven years by the Leeds company for use in India. Another important point to note here is that the year of supply of the first of these locomotives, No. 1322 of 1896, was the same as that for Lachesis. Just for good measure, the pattern of motion bearings shown in the 1903 works photograph of No. 1615 is also the same as for Lachesis (a surviving General Arrangement for No. 1322 confirms that this pattern was in use on that locomotive), as is the stated coupled wheel diameter of 1ft 8in. Taking all these observations into account, there is little doubt that the rolling chassis assembly for Lachesis was supplied from Manning Wardle’s Boyne Engine Works. Further examination of the records relating to both narrow and standard-gauge Manning Wardles also confirms that the same was true of the canopy components. Although the Leeds company had lost its ability to sell new locomotives directly to the Arsenal authorities in 1889, its influence on RAR locomotive practice did not end in that year.

The power transmission arrangement of Lachesis deserves detailed consideration, and it is known from Hornsby drawings relating to the 2ft 6in and 18in-gauge locomotives completed in 1903–04 that some components at least would have been outsourced. A spur gear on the left-hand side of the crankshaft engaged with another that was loosely mounted on the reverse/speed selection shaft. This latter gear was laterally attached, via a journal, to the left-hand bevel gear of the reverse gearbox which also ran loose on the shaft. The bevel gear engaged with another, mounted above on a vertical shaft on the vertical centreline of the gearbox, which in turn engaged with the right-hand bevel gear (again running loose on the main shaft and with an integral journal running in a gearbox bearing). Between the right- and left-hand bevel gears, the main shaft was surrounded by a rigidly mounted friction cylinder which in turn was surrounded by a grooved selection plate provided with limited lateral but no rotational freedom relative to the cylinder. This plate was configured to be able to engage (when moved sideways) with one of the dogs attached to the inward ends of clutch springs surrounding the friction cylinder. These springs were attached at their outward ends to the inner faces of each of the right and left bevel gears. By this means, selection of forward or reverse gear could be accomplished by swinging the footplate-mounted reverse lever leftward or rightward as desired until secured in its limit of travel by a spring catch. This rotated a longitudinal shaft (mounted slightly to the left of the chassis centreline) upon which was fitted an upwardly projecting bellcrank whose upper end was configured to engage with the selection plate groove. Moving the selection plate laterally to engage with one of the spring dogs would engage either the left-hand bevel gear (which would rotate in the same direction as the input spur gear) or the right-hand one (which would rotate in the opposite direction). The oppositehanded ‘threads’ of the clutch springs were configured so that each, when selected, would tighten around the friction cylinder, producing rotation of the main shaft in the desired direction.

Once the engine was in motion, speed selection was accomplished in a manner allowing for two speeds in either direction as follows: the speed selection pedestal was located on the right-hand side of the cab footplate and upon it in the vertical plane were mounted two levers, each rigged so that they could enjoy a limited inward rotational travel but restrained by a notched bar and dog interlocking mechanism so that their respective movements could not take place together. Each lever was affixed at its lower end to a longitudinal bar upon whose leading end was fixed an upward-projecting bellcrank. Each of these bellcranks was arranged so as to engage at its upper end with its respective spur gear, each of which was mounted (so as to enjoy limited lateral freedom) on the right-hand portion of the main gearbox shaft. These gears, as with their selection shafts, flanked the side mainframe. Rotation of the interlocking bar in the desired direction would thus free the chosen speed lever so that it could be moved inwards by its permitted travel and secured by a spring catch. This would push the chosen spur gear laterally on the gearbox shaft into mesh with its counterpart on the jackshaft. Reversing this process would disengage the previously chosen speed and allow for the interlocking bar to be moved into the horizontal (‘neutral’ position preventing movement of either lever) or ‘alternative’ position facilitating selection of the other speed. The Hornsby catalogue claimed a performance for a locomotive of this type of haulage of 70-ton loads on the level at a speed of 3 miles an hour or 40 tons at 5 miles an hour.

The Royal Arsenal authorities did not give up on the quest for safer alternatives to steam motive power in the vicinity of Danger Buildings following the unsatisfactory results with compressed air units in 1877–81. In 1896 Richard Hornsby & Sons Ltd of Grantham produced the first of five medium-to-heavy oil ‘hot bulb’ four-stroke compression ignition locomotives for use in Danger Buildings on the RAR. Four of these were of the customary ‘single piston’ variety and the earliest example, Works No. 1705 of 1896 Lachesis, is shown in this front right-hand three-quarter maker’s photograph. The unit essentially consisted of an ‘ordinary’ maker’s-pattern oil engine with ‘agricultural’-style water cooling system and geared transmission mounted on a modified steam locomotive pattern chassis. In order to adapt the Akroyd engine to this particular form of use, the fuel tank had to be relocated from beneath the engine assembly (where its place was taken by the water tank) to beneath the canopy footplate on the right-hand side of the locomotive. The reverse gearbox (immediately behind the cooling tower) will be noted, as will the speed choice gears (in the foreground and controlled from the pedestal on the right-hand footplate) and final jackshaft drive to the rear axle. Close inspection of the mainframes reveals their similarities (apart from the sloping horns to minimize suspension loadings on the jackshaft rod) to Manning Wardle 2ft 6in-gauge 0-4-0Ts Nos 1322, 1526 and 1615 for India; the same is true of the motion components and bearings. The canopy is recognizably similar to the design found on Manning Wardle 18in-gauge 0-4-0STs Nos 1201, 1818 and 2039 for Argentina (although the supporting brackets on the upper ends of the leading stanchions have been rotated inwards by 90 degrees to engage with the leading canopy valence rather than the side valences), while the 1ft 8in wheel diameter found on all the Manning Wardle locomotives mentioned in this caption was also found on Lachesis. All these features would have been strongly indicative of a Manning Wardle origin for most of the ‘rolling chassis’ of Lachesis, even if Hornsby Drawing No. 14453 had not survived to prove the point beyond doubt. The 1895 date found on Drawing No. 14453 for the wheelsets, suspension and axleboxes of Lachesis suggests that Manning Wardle supplied its rolling chassis and jackshaft rods to Hornsby in the early months of 1896. (Maker’s photograph)

The location of the transmission gearing on Lachesis caused something of a headache from the chassis design point of view in the provision of adequate lateral staying at the leading end as it precluded the mounting of a conventional frame stretcher in the position level with what would have been the motion brackets on a steam locomotive. This difficulty was partly solved by anchoring the rear of the cooling tower to an asymmetrical stretcher between the upper extensions of the mainframes (which secured the reverse gearbox), and anchoring the bottom of the cooling tower at its leading end to the front bufferbeam. Although this arrangement appears to have proved adequate during the early years of the locomotive’s existence, it was, as we shall see, superseded on the subsequent early Hornsby locomotives.

During the first decade and a half of independent locomotive operation, with the exception of units built for experimental purposes, the Royal Arsenal authorities had been able to choose the locomotives that were purchased for use in ordinary traffic on the internal railways. However, the position was to change dramatically after this time as a consequence of historical events elsewhere. In order to understand why this was the case, it will be constructive to review these events and their impact on the railway practice of the Royal Engineers in greater detail. From 1870 until 1896 (for locomotive haulage) and 1900 (for hand or animal working) the Royal Engineers adopted 18in gauge as its ‘trench tramway’ gauge and lines built to this dimension were designated to be used in connection with the support of military sieges regarding such duties as supply and armaments conveyance, water transport and the construction of wider-gauge railways. The earliest experiments in this respect were carried out at Aldershot in 1872–4 with John Barraclough Fell’s ‘trestle railway’ utilizing a long-wheelbase Manning Wardle 0-6-0 Ariel (Works No. 412 of 1872) fitted with safety guide wheels. Failing to gain satisfaction with this rather impractical system (ostensibly on the grounds of its non-adoption elsewhere), the Royal Engineers turned to another possible solution in their attempts to solve the problem of transporting men and materials over difficult terrain. The idea that they experimented with was the ‘Handyside Steep Gradient Apparatus’ patented between 1873 and 1876 by Henry Handyside. This was tested in the latter year by a standard-gauge Fox, Walker 0-6-0ST on the Hopton Incline of the Cromford & High Peak Railway. In essence it allowed locomotives to operate in their normal mode on the level but on gradients of between 1 in 20 and 1 in 10, the locomotive could ascend light and, by means of special gripping struts, be held at some point on the incline. A built-in steam winch would then be used to haul the wagons to the point of rest where they would be held, possibly by means of gripping struts, while the locomotive ascended further, paying out the towing cable as it went until the ascent was completed in a caterpillar fashion. The Royal Engineers were sufficiently impressed with the basic principle to purchase six Handyside 2-4-2T locomotives, Works Nos 399–404, from Fox Walker & Co. of Bristol in 1878, two of which were tested on the eastern part of the Arsenal’s railway system and a third at the School of Military Engineering in Chatham.

This rear right-hand three-quarter view of Lachesis shows the handbrake column (covered by a conical valence), the handwheel and first (internally-toothed) pinion for the fan supplying air to the hot bulb lamp, the cover and exhaust pipe for the hot bulb lamp, the ‘speed gear’ pedestal, and much of the detail pertaining to the cylinder, camshaft and connecting rod. The cooling water was pumped from the cylinder water jacket though the ‘thin’ pipe (as opposed to the ‘thick’ main exhaust pipe) to entry via a manifold to perforated header pipes located within the top of the cooling tower. The water would then drop through the inside of the tower, being cooled by the upward draught induced by the main exhaust, whereupon it would be collected at the base and recirculated through a filter located beneath the cylinder assembly. (Maker’s photograph)

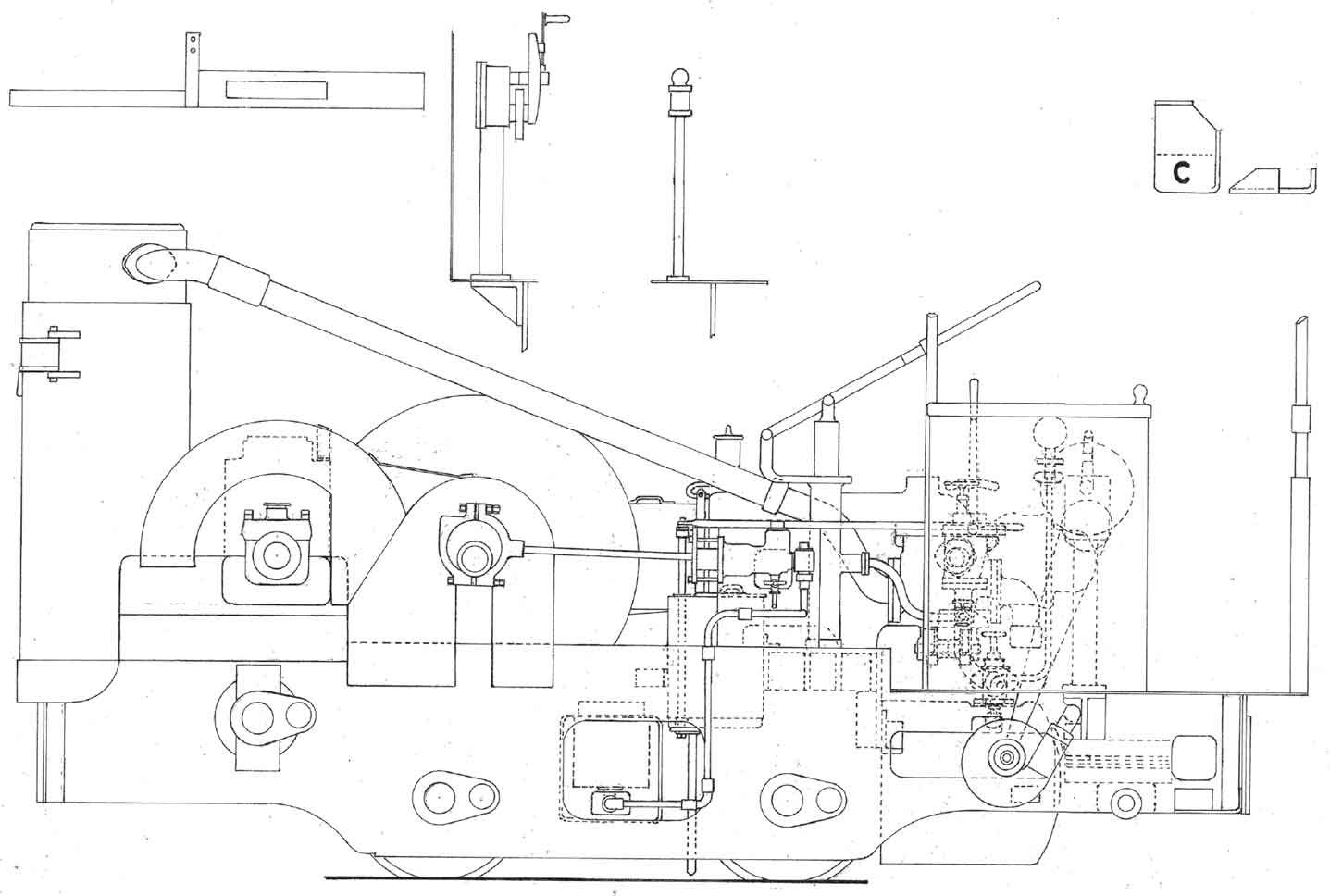

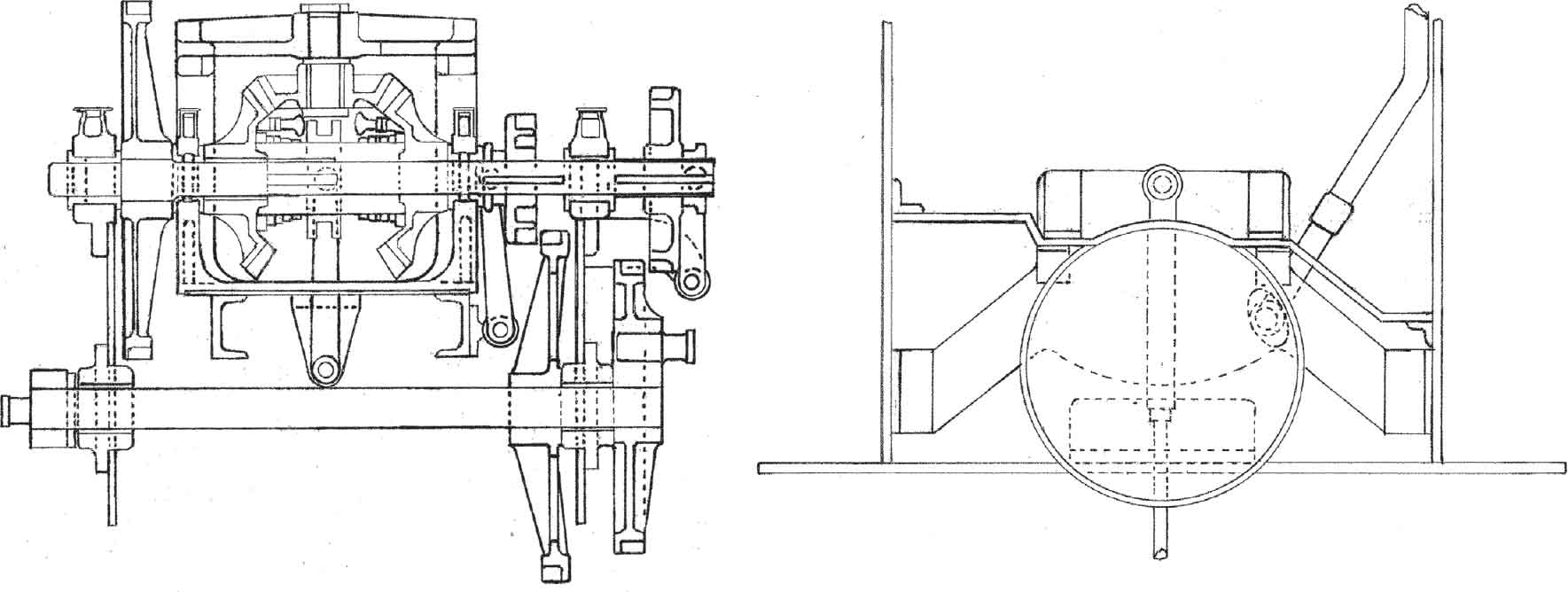

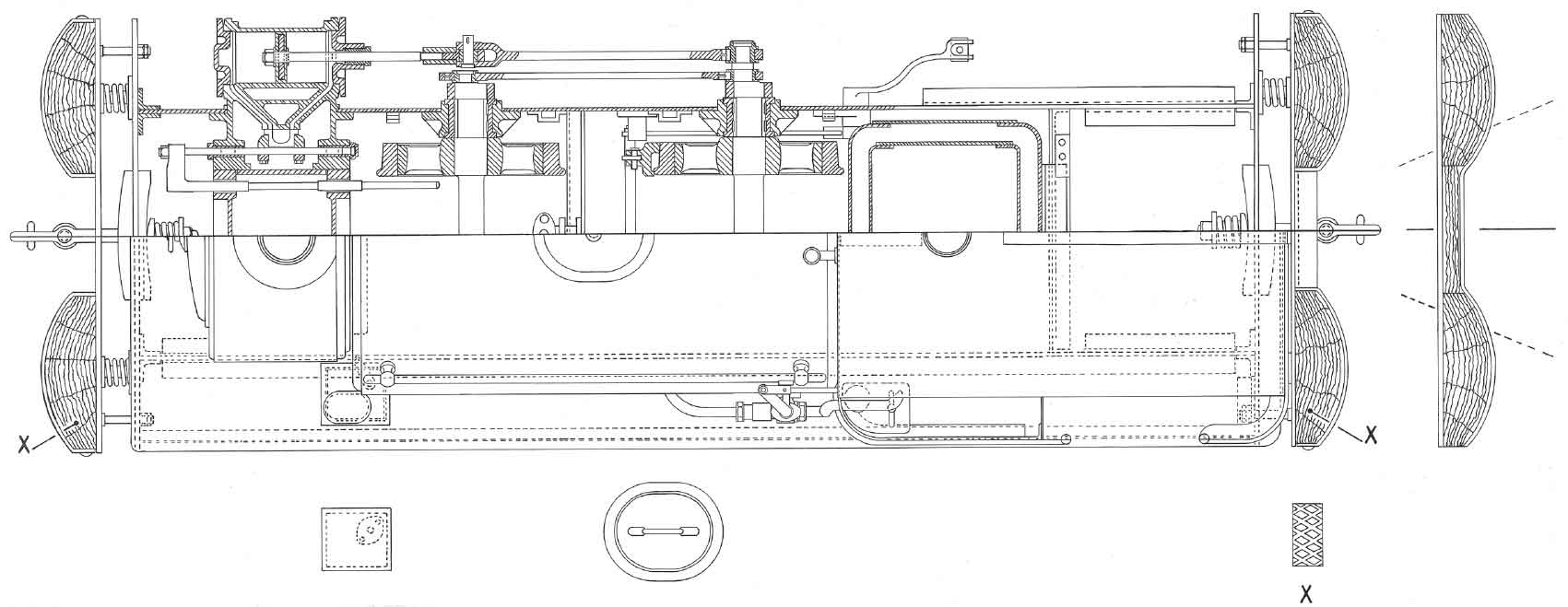

These are reconstructed drawings of Lachesis from the known details, surviving R. Hornsby General Arrangement No. 14330 and the few surviving Component Drawings 14178, 14321, 14453, 14587 and 14613. The first drawing comprises a right-hand elevation showing such details as the speed selection gear, oil injection apparatus, governor, camshaft, water return pipe and (in ‘exploded’ form) the right-hand sandbox and guard for the extreme right-hand speed gear. A feature of special note is the design employed for the drawbars, in which the flexibility was obtained by the use of integral triangular forgings. One note of caution in reading the drawing is that the fuel oil delivery pipe from the pump (the pump being actuated by the air admission rocker) overlies part of the water return pipe from the cooling jacket for the oil admission chamber for the vaporizer. Appended to the right-hand elevation is a rear elevation showing (left) the hand fan for the vaporizer lamp and air starting reservoir with pressure gauge, valves, pump and associated piping with (directly above) the oil engine ‘valve box’ and exhaust pipe. Moving towards the centre, the vaporizer can be seen with (shown by dotted lines) the preheating lamp and air pipe from the hand fan (shown cut away). Beneath the cylinder can be seen the air admission rocker, while mounted on the right-hand side of the vaporizer can be seen the water-jacketed oil injection chamber. The pipework associated with this comprised a loop from the water circulation system for the jacket and an oil connection from the pump with an overflow connection returning to the fuel tank, whose level of usage would be determined by the action of the governor. On the right-hand side of the footplate can be seen the handbrake column, almost certainly of Manning Wardle manufacture but ‘disguised’ by a conical valence, and (in a more forward position) the speed selection pedestal, with its associated anti-simultaneous selection interlocking gear visible.

The left-hand ‘scrap’ view shows such details as the exhaust pipe leading to the cooling tower, the water circulation pump and piping, the compressed air starting reservoir and associated valves and pump, and the guards for the left-hand flywheel and intermediate transmission gearing, while the safety shield for the oil engine connecting rod (omitted from the right-hand view) is shown in place. The components shown in ‘exploded’ view are the guards for the transmission gearing, the pedestal for the vaporizer lamp fan gears and upper pulley, the oil tank vent and the plan and rear-end views of the cab step (the portion marked ‘C’ being of chequer-plate configuration).

The third view shows the transmission system employed by the Hornsby locomotives at Woolwich. The forward/reverse selection shaft (actuated by a lever on the footplate) ran longitudinally along an axis bisecting the body of the reverse gearbox (but offset to the left from the centreline of the locomotive). From this, a bellcrank engaged with a sliding collar on the driveshaft which was fitted with recesses so as to be able to engage one or other of the dogs on the contra-wound forward or reverse springs, one of which was attached to the left-hand bevel gear and the other to the right-hand one. The bevel gears were permanently in mesh, with the left-hand one being integral with the intermediate transmission gear, and both left- and right-hand bevel gears were free, when in neutral, to rotate relative to the driveshaft. Selection of forward or reverse gear would cause the collar to grip one of the spring-dogs, thereby causing the spring to grip a drum mounted on the driveshaft and engage the drive in the desired direction. The two longitudinal shaft and bellcrank assemblies for the speed gears can be seen on the right-hand side, with the interlocking mechanism being visible, as previously referred to, in the rear elevation of the locomotive.

The final view shows the leading drawbar stretcher. Its configuration was determined by the position of the transmission gearing. It had to be incorporated into a subframe with the cooling tower body and its associated frame spacer in order to (theoretically) create a suitably rigid front-end assembly for the locomotive. In reality, the arrangement did not prove to be satisfactory in service. (Author)

It was clear from the test results that although at least some elements within the Royal Engineers did not dismiss the ‘Handyside principle’ out of hand (although they envisaged the winch apparatus being accommodated in a separate truck, presumably with a ‘ball and socket’ flexible steam coupling to the locomotive), there were a number of problems with the locomotives from a mechanical point of view. Their design had been somewhat hurried, owing to the threat of Britain being involved in a conflict in the Balkans in 1878, they lacked a suitable coiling apparatus for the winch, and initially at least their reliability was poor. With the immediate threat of a Balkan conflict gone, in 1881 the RE Committee decided that further 18in-gauge locomotives for siege train purposes were not necessary, but other events during the following two years forced a de facto re-think of the situation. During 1882, some six locomotives of 18in gauge built by John Fowler & Co. of the Steam Plough Works, Leeds, had been supplied for military purposes, probably construction work, in Cyprus and India. These were built under Greig & Beadon Patent No. 402 of 1880 and employed an indirect jackshaft drive in order to keep the cylinders, connecting rods and big end bearings further away from possible damage caused by dirt and lineside obstructions. Nearer home, two locomotives were required for an 18in-gauge construction railway linking Forts Luton, Horsted, Bridgewoods and Borstal on the outskirts of Chatham. The opportunity once again arose for the design of an 18in-gauge locomotive suitable for possible call-up for direct military purposes and it was seized upon by Major Thomas English RE, who had probably been involved with improvements to the design of the Greig & Beadon locomotives and had definitely been involved with the supply of two of them to Cyprus. What eventually emerged for the Chatham system was an 0-4-2 back tank with integral equalized ‘spring beam’ suspension (as used on the later Greig & Beadon locomotives) for the coupled axles, 7.5in x 12in outside cylinders and valve chests, a ‘middle dome’ boiler barrel and Belpaire firebox, inside Gooch ‘stationary link’ motion actuating the valves through rocker shafts, three-piece side mainframes (linked into a single assembly by their stretchers) to accommodate the firebox and trailing truck, and a design of trailing truck credited to Major English under a void patent application (No. 3869 of 1883) that involved side control by means of a sprung ‘crankshaft’ assembly. This truck design was later to be employed on four of the RAR Hornsby locomotives as built, with the prototype eventually following suit. The ruling gradient on the locomotive-worked main line of the Chatham Fortifications system being only 1 in 43, thoughts of using a Handyside winch were quietly abandoned and the minimum recommended curve radius for the new design was 35ft instead of 15ft for the Handysides.

As we have seen, one of the most obvious consequences of the unification of the Royal Arsenal Railways system and its takeover by the Royal Engineers for instructional purposes was an influx of Royal Engineers’ locomotives rendered surplus to other requirements by such factors as the failure of the 1885 Suakin campaign, the 1896 decision of the Inspector-General of Fortifications to dispense with locomotive haulage on front-line 18in-gauge track, and the completion of substantive building work on the Chatham Eastern Defences. The aftermath of this latter event was to make the Eastern Defences (or Borstal line) redundant. One of the most peculiar designs to pass through Royal Engineers’ hands was represented by the six Fox Walker Handyside 2-4-2Ts of 1878 (Works Nos 399–404) originally ordered in response to the threat of unrest in the Balkans, but found to be unfit for their intended front-line purpose after trials on Erith Marshes and at Chatham. This illustration shows the class as originally delivered to the Royal Engineers and emphasizes the gripping shoes for holding the locomotive on steep gradients and the front-mounted winch for the haulage of rolling stock on steep gradients. (Maker’s photograph)

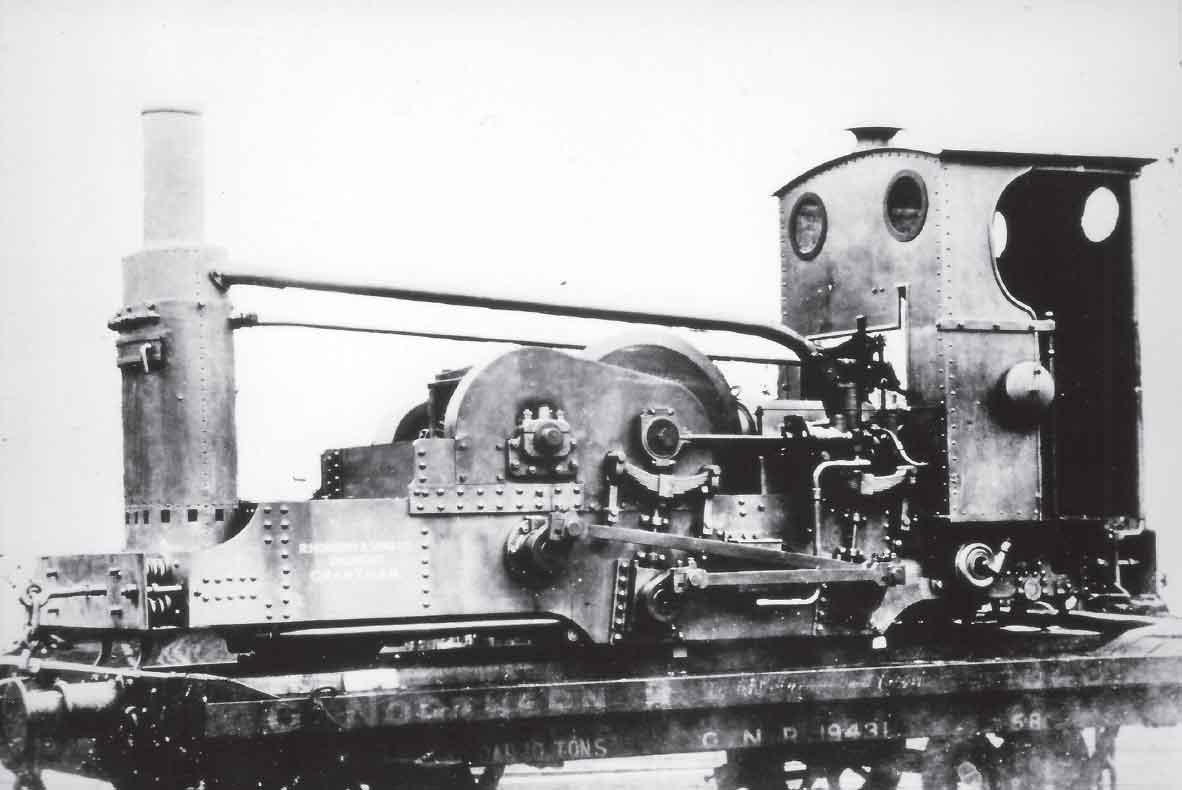

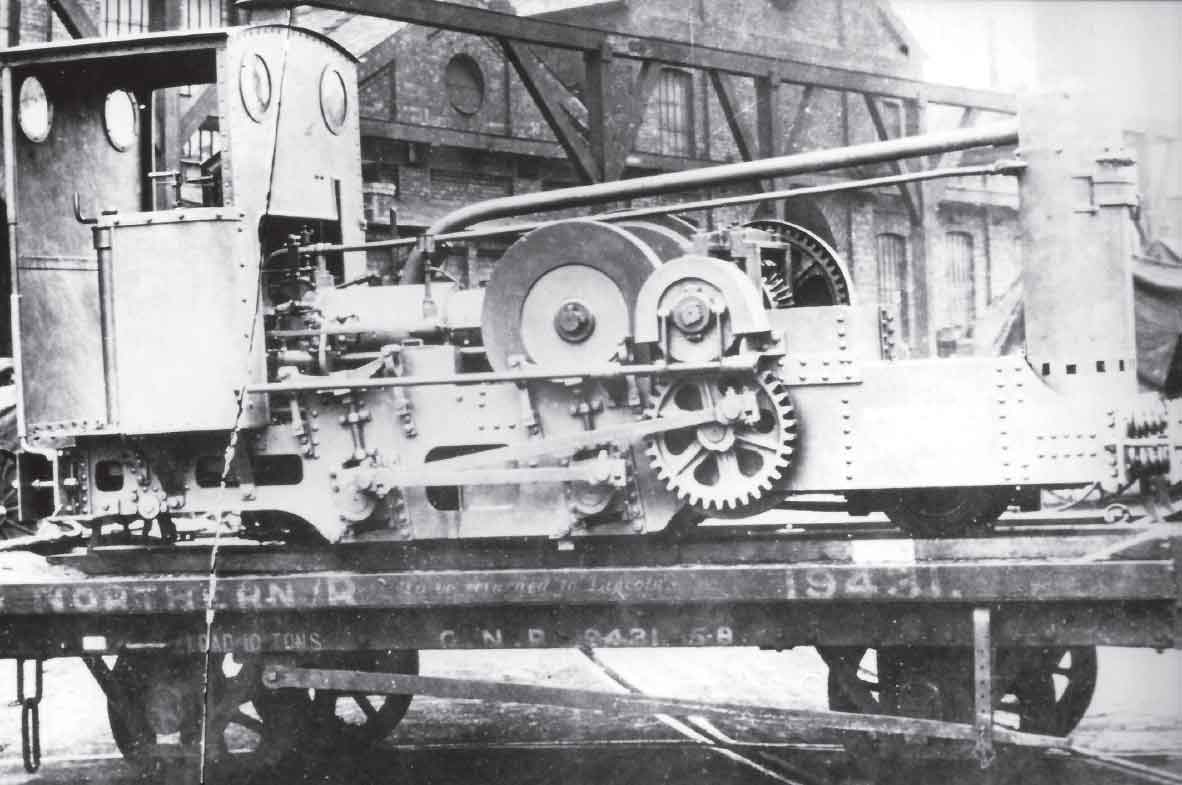

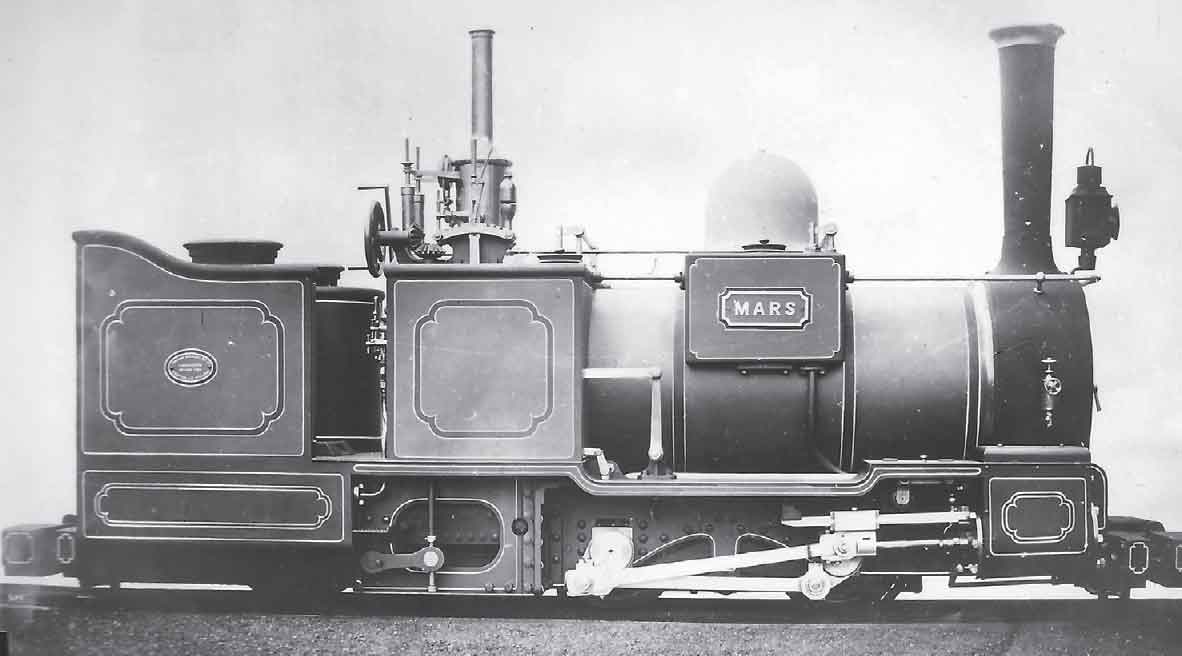

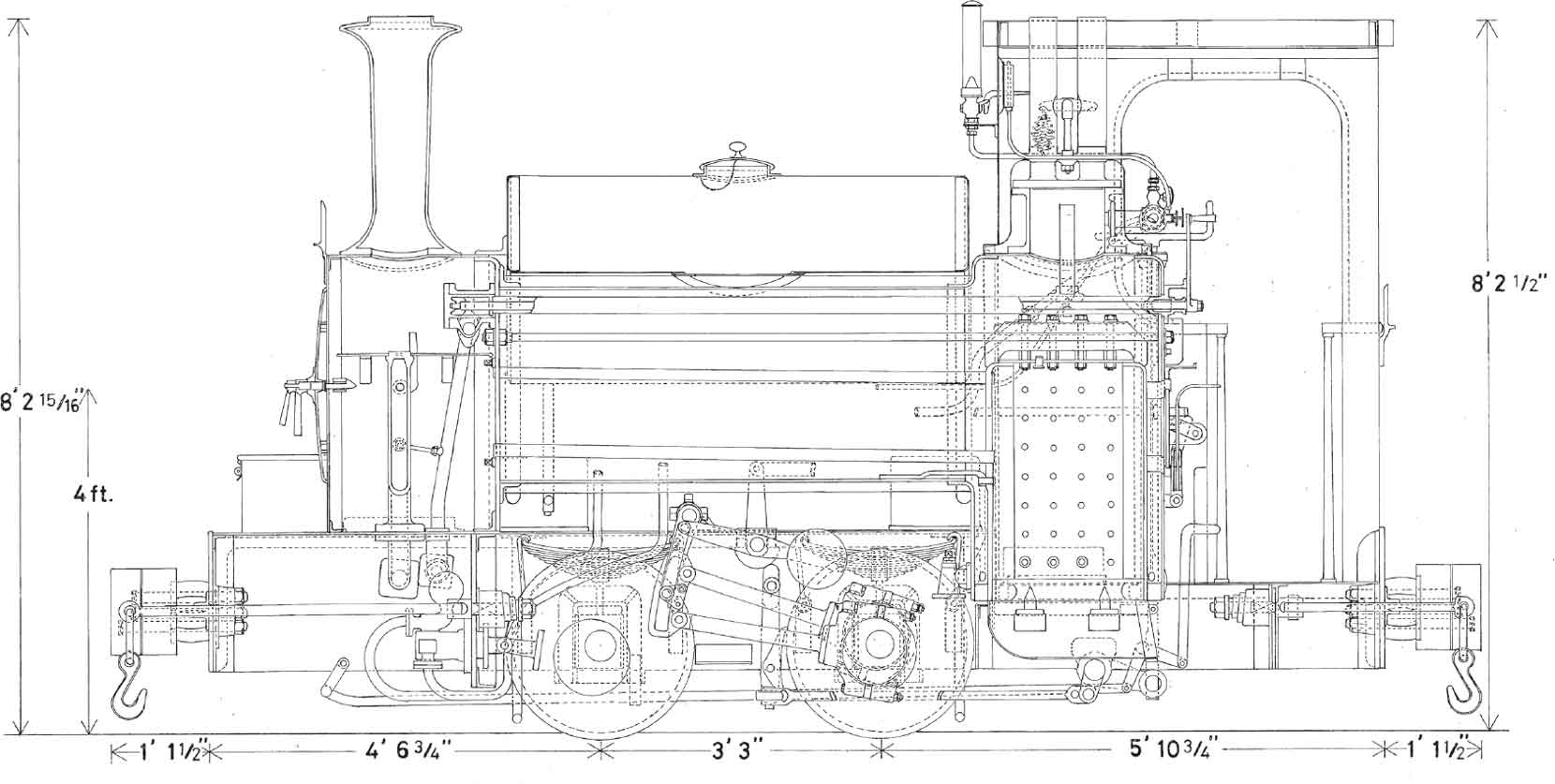

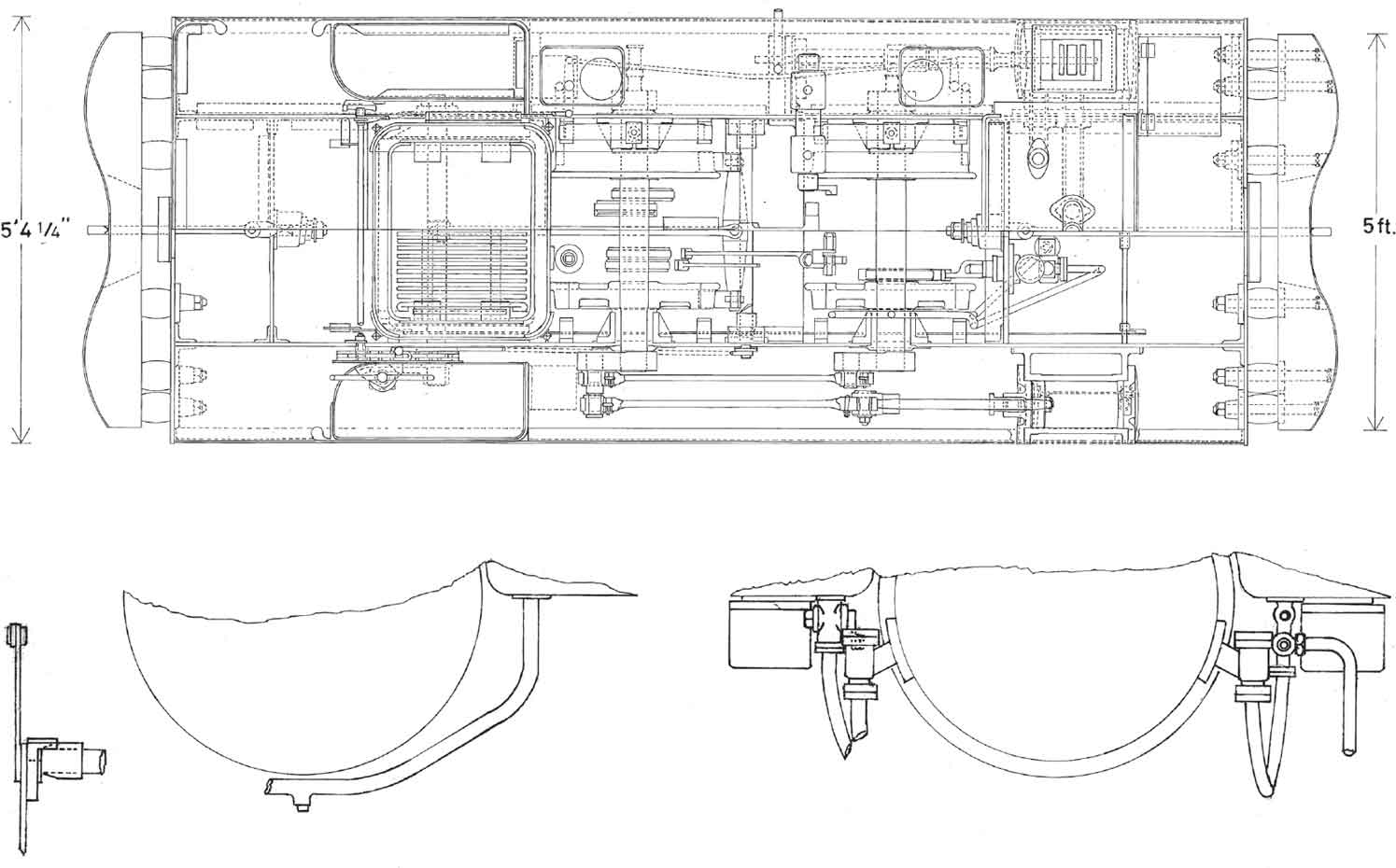

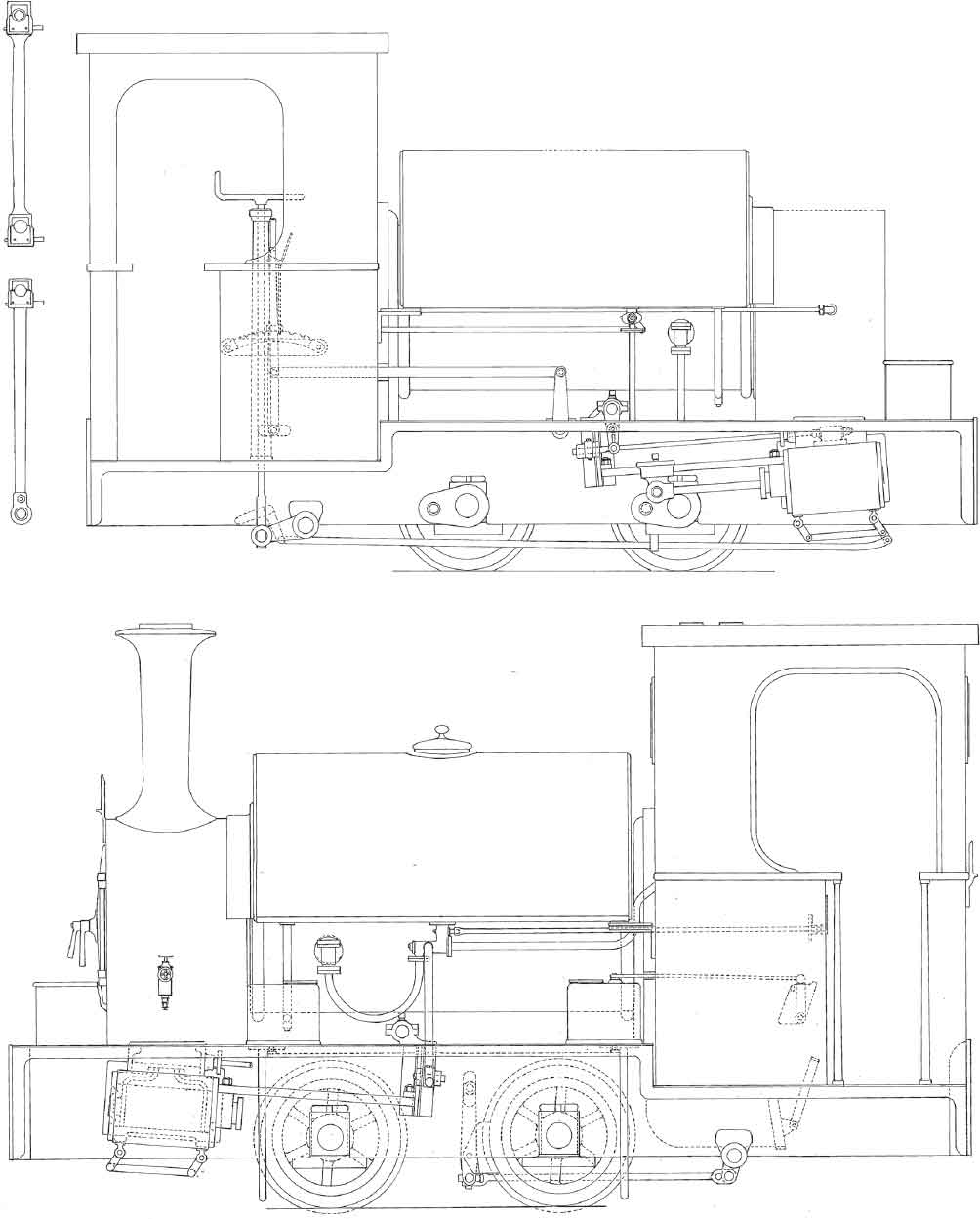

At the time of ordering the new locomotives, Major English would probably have liked to use John Fowler & Co. as supplier (as he had strong links with the firm), but he was overruled by his colleagues who perceived Vulcan Foundry as a better bet. The locomotives therefore emerged as Vulcan Works Nos 939 of 1883 Vulcan and 1075 of 1884 Mercury and were put to work hauling convict carriages on the Fortifications line.