Rolling Stock Used Within the Arsenal

Following completion of the first phase of the ‘Iron Railway’ within the Arsenal and the initial carriage in 1824, the manufacture of ‘eight carts for the iron railway’ was approved by the Board on 23 March 1825. In reality, these were four dray carriages at a cost of £20 each and four carts at a cost of £30 each, £200 in all. Details of these early items of rolling stock are sketchy, but it is known that the very earliest items were manufactured by the Royal Carriage Department. The most reliable guide to their design is offered by a surviving drawing of ‘Tram Turntables Installed at the Shipping Pier’ in The National Archives (WORK 43/1560) showing a cast-iron wagon turntable and ‘mainstream’ permanent way consisting of angle irons whose upper horizontal surfaces formed the running lines and vertical faces formed the flanges (and hence defined the gauge). This drawing dates from 1860 and is therefore a relic of the period of transition from the Iron Railway to a more conventional system (the main railway network had, as we have seen, ‘penetrated’ the confines of the Arsenal during the previous year). The gauge of the Iron Railway appears to have been approximately 3ft 10in and the ‘square’ configuration of the running grooves in the turntable suggests that the wheelbase of the rolling stock could not have been more than about 4ft. The rolling stock appears to have been very rudimentary in construction, being short-wheelbase four-wheeled horse- or manuallypropelled vehicles, mainly of timber construction and strengthened with iron straps or plates where necessary. In some respects it would not have been unlike the items in use on the Surrey Iron Railway between 1803 and 1842.

The exact date of completion of the replacement of the Iron Railway with conventional standard-gauge permanent way cannot be stated with certainty, but it would appear to have been accomplished by 1862. O.F.G. Hogg refers to the RGF constructing a railway from the gun boring mill to the proof butt in 1859 for £6,000, a ‘general’ railway being built to the shipping pier during the following year for £1,000, and a ‘general’ railway extension in 1861 for £2,600, while further railway extensions were built for the Royal Laboratory in 1862 and the Royal Gun Factory in 1867 for £2,000 and £1,000 respectively. A map of the Arsenal surveyed in 1864 and printed in 1866 shows an internal railway system, albeit one that still incorporated many wagon turntables, connected to the SER Hole-in-the-Wall siding at a point slightly to the north of the original (northern) Canal Swing Bridge. Hogg further records:

a standard gauge track had connected the Arsenal with the L.C. & D. [sic] main line sidings at Plumstead since 1876. It entered W.D. property at the ‘Hole-in-The-Wall’ so named from the large hole that had been made in the then considered impregnable wall surrounding the southern side of the Arsenal, thence it ran north over the Canal by a Swing Bridge near the ‘Tay Bridge’ Sidings. These, constructed in 1879, are the present D42B Sidings. The line then passed to the Coal Dock at the eastern end of the West Wharf to form an exchange point with the narrow gauge system. L.C. & D. locomotives worked over this system until 1890 when the introduction of standard gauge locomotives enabled the Government to use its own full-sized engines.

There are several difficulties with Hogg’s assertions that are immediately apparent from the surviving evidence. Firstly, as we have already seen, the standard-gauge siding was constructed in 1859 and connected the Arsenal with the South Eastern Railway, not the LC&DR. Secondly, again as we have already seen, standard-gauge locomotives were purchased by the Arsenal from 1875 onwards, not 1890. The ‘Swing Bridge’ to which Hogg refers was the Middle Swing Bridge which was not completed until between 1888 and 1893 (National Archive WO78/3008), and hence could not have been part of the route of any mainline locomotives and rolling stock ahead of that date. It does appear that, prior to the unification of the Arsenal’s railway system, SER locomotives and rolling stock would have had reason to work over more of the internal system than was the case in 1909, by which time the E101 purpose-built exchange sidings (embryonic in 1893 shortly after unification) had been completed. The existence of a de facto handover point close to the eastern part of the West Wharf in the pre-1890 period, as suggested by Hogg, would have been the consequence of the fragmented operational procedures of the Arsenal’s railway system and the location of the factories and storehouses at this time. The route actually taken by SER locomotives (i.e. by crossing the original Swing Bridge) would have involved negotiating a curve of approximately 130ft radius (which constituted part of the triangular junction between the SER feeder siding and the above-mentioned proof butt line constructed during the same year). This was not necessary from the late 1890s onwards when the site of what was to become E101 became the customary handover point which, as we have seen, it performed ‘solo’ until augmented during the First World War.

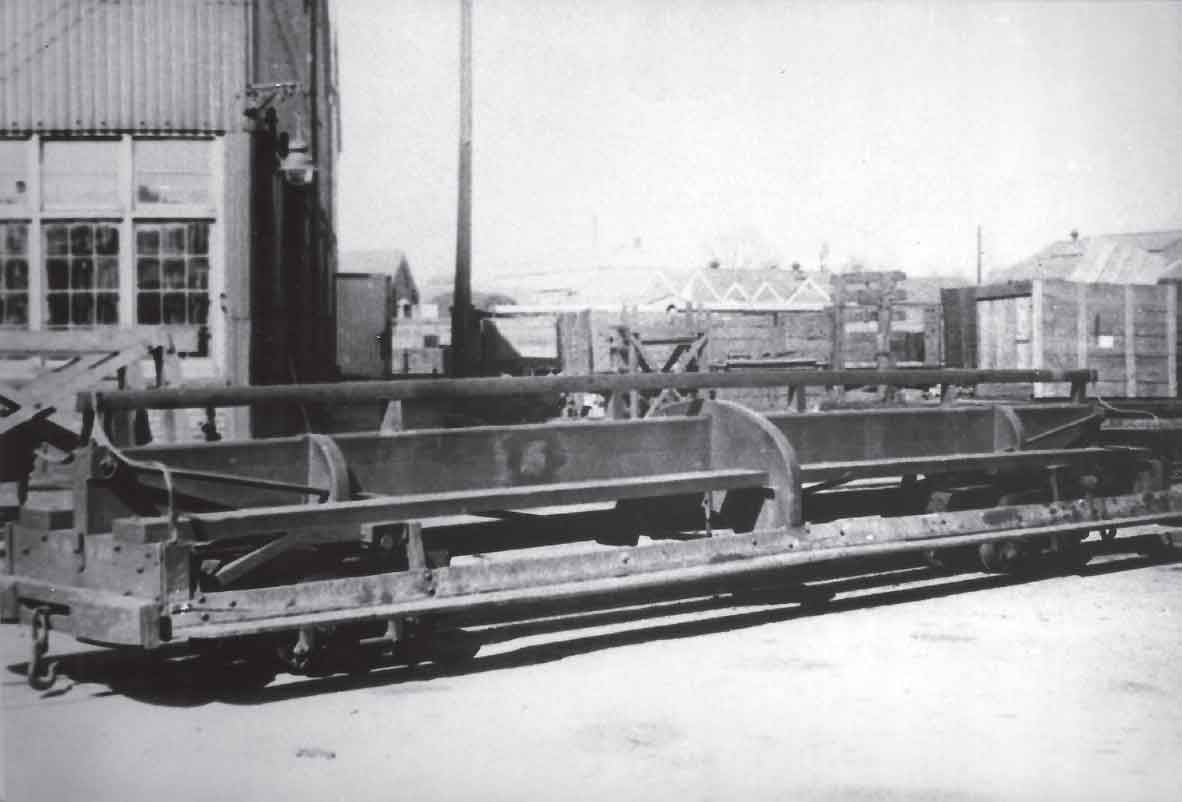

What were the implications of the pre-1890s state of affairs for the design of early standard-gauge rolling stock used on the Arsenal’s railway system? It has to be remembered that the relevant early traffic could be divided into two categories, i.e. that which could be conveyed in standard (or only slightly altered standard) pattern rolling stock, such as coal or even some ammunition, and that which had to be conveyed in specially-built vehicles such as large gun barrels. With regard to the former, with long-distance operation not a priority, a culture of acquisition of second-hand wagons from mainline companies quickly established itself and this was to persist well into the later history of the RAR. As with the locomotives, the failure of the Suakin-Berber Railway campaign of 1885 was to leave its mark on the RAR’s rolling stock situation, even to the extent of providing its first standard-gauge passenger vehicles. The early vehicles designed for dealing with large artillery pieces appear to have been constructed by the Royal Carriage Department, as they were designed in-house and private rolling stock builders at this early stage would have lacked suitable experience for construction of such items. A recently-discovered photograph shows some of the early gun barrel wagons which were timber-framed ‘eight-wheelers’, each running on two inside-framed bogies, and one of which is accompanied by a four-wheel match truck fitted with the early pattern of composite buffer. A more sophisticated design of vehicle was needed when it came to ‘proving’ the guns. The earliest reliable illustrations of such a device appear in The Graphic and the Illustrated London News in 1876, showing a vehicle carried on two six-wheeled channel-framed bogies and fitted with composite buffers. The barrel-bearing iron superstructure was substantially built and when viewed side-on was rather skip-like in appearance. This was the design of vehicle used in the well-documented 81-ton muzzle-loader tests carried out at Shoeburyness in during the same year and referred to in Chapter One.

The development of larger breech-loading guns during the 1880s required the Royal Carriage Department to construct larger proof sleighs and we are fortunate that a specimen from this period survives. This 86-ton vehicle was built in 1886 and, as an indication of the contemporary use of heavier running rails for proof sleighs when compared with the muzzle-loader tests, it is carried on two four-wheel bogies, giving an approximate loading of 45 tons per axle when supporting a typical gun of the period as opposed to 20 tons for the 1876 sleigh. The 1886 sleigh owed its survival to its latter-day pairing with 18in howitzer barrel L1 which was used in tests at Shoeburyness into the 1950s.

Although they were not brought into use at Woolwich until the early twentieth century, the ex-Suakin carriages will be dealt with at this point owing to their date of construction and their arrival shortly afterwards into storage at the specially-built railway depot. These carriages were constructed by Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Co. and two of the three basic designs eventually found their way into RAR stock. The one design that proved unsuitable for use on the RAR’s tight curves was a ‘rigid eight-wheeler’, and two representatives were transferred from storage at Woolwich to Shoeburyness in 1900 where they remained in use into the 1950s. Today one survives, albeit with a much altered body, at Chatham Historic Dockyard. The larger of the designs used on the RAR were the previously mentioned American bogies. Sadly no maker’s drawings are known to survive for these carriages, but the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s Report for 1914–18 states that they were saloon carriages 55ft long and 9ft 8in wide and were carried on two fourwheeled bogies. It is known from photographic evidence that they were fitted with double-skinned roofs to cope with the climatic conditions prevalent in their original intended destination. According to Roberts, they proved unsuitable for their duties at Woolwich owing to the sharp curves and restricted loading gauge found on the RAR system. Following their withdrawal from service during the period of the report, two of their bodies were converted to dining rooms while the third was used as the office for the locomotive running section. The chassis of one of these carriages was adapted as a 20-ton gun truck, while those formerly belonging to the other two remained in reserve in 1918 with a view towards similar adaptation. However, the Armistice ensured that in all probability this was never undertaken. The remaining type of ‘Suakin’ carriage used by the RAR was a four-wheeler and the evidence for its appearance at Woolwich was in the writings of P.E.W. Scott:

There were some interesting service vehicles, viz a couple of 4-wheel coaches dating from the Suakin and Berber Railway, used by the P.W. Department as mobile homes for the platelayers. These still retained slatted windows and sun visors, and to see one of them parked on a siding down on the marsh on a cold winter’s day was, to say the least, incongruous.

It has to be remembered that Scott’s notes relate to the 1940s when more modern passenger carriages had been acquired and there is no reason to suppose that these vehicles had originally been used on the RAR for anything other than normal passenger conveyance.

The extent to which wagons from the abortive Suakin campaign found their way into RAR stock cannot be exhaustively assessed today, but Scott’s notes continue: ‘there were also a number of 4-wheel water tenders from the same railway, used in the Arsenal as fuel oil tanks by the Loco. Dept.’ These items had originally been constructed by Manning Wardle to accompany the Suakin locomotives, and they would have come into their own latterly with the arrival of the standard-gauge diesel locomotives, having presumably earned their keep during the intervening years by supplying fuel for the oil-fired steam locomotives. It seems certain, given that only one locomotive chassis was used in an oil tank conversion, that one of the portable oil tanks recorded at QFCF No. 4 and Mugby during the year ending March 1917 would have been an ex-Suakin tender, or possibly two or more coupled together. Archive drawings survive for covered goods, stores and brake vans for the Suakin-Berber campaign, and while it is not known for certain whether any or how many of these items found their way into RAR stock (a brake van of this design was later used at Shoeburyness), there is a considerable likelihood that some at least managed to do so.

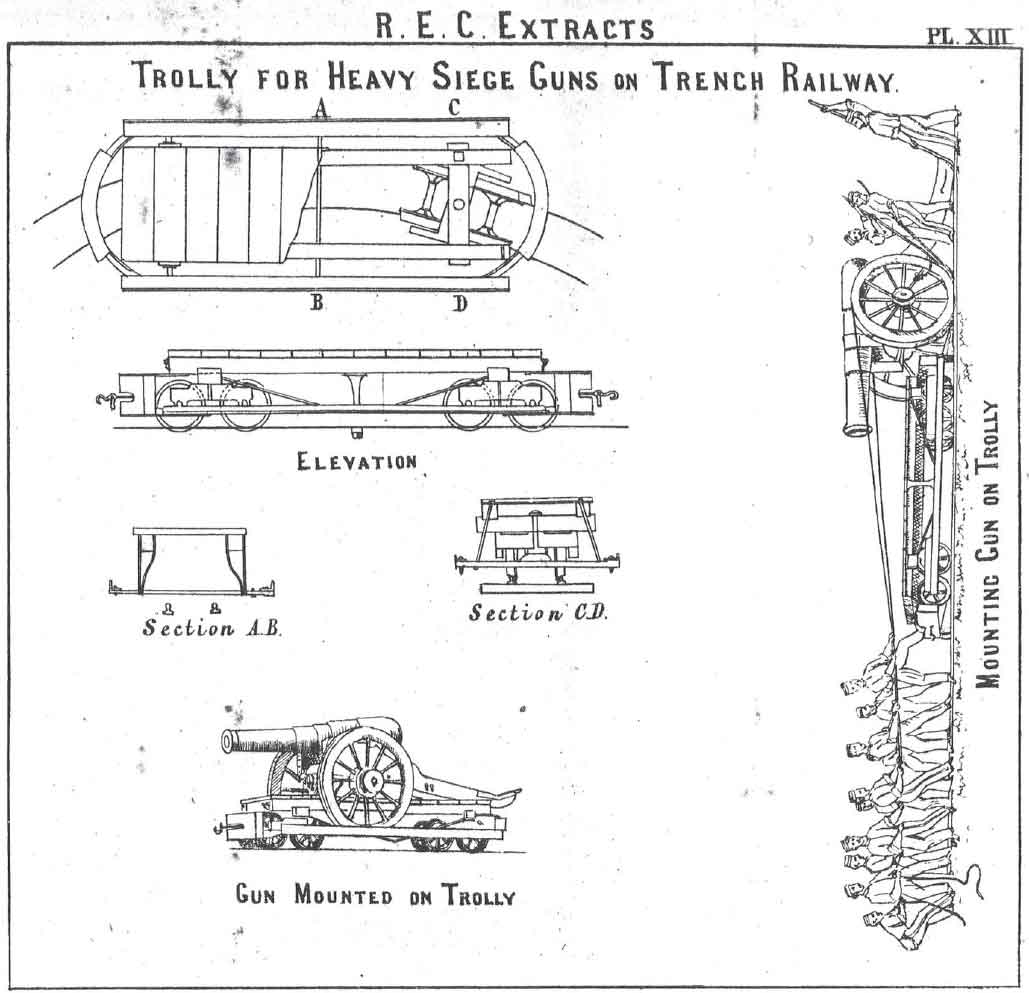

The development of early 18in-gauge rolling stock within the Arsenal is virtually unrecorded in the professional journals of the late nineteenth century, partly as a consequence of the existence of a very detailed article in Engineering in 1875 covering the rolling stock in use at the time at Chatham Dockyard. Although the latter’s 18in-gauge system was always under Admiralty rather than Royal Engineers control, there is no doubt that there was much sharing of influences during these formative years (for instance, the first locomotive purchased for the RE ‘Park’ Railway at Chatham, Burgoyne, followed the Dockyard’s Busy Bee in its design). The influence of early dockyard practice at the Arsenal can also be detected in the use of bogie ‘knifeboard’ carriages by 1881 and the use of bolster wagons, as exemplified by the illustration of Lord Raglan after rebuilding with its later chassis arrangements. Many of the early four-wheeled wagons, such as those used for the carriage of coal or lighter loads, were also similar in design to their early Chatham counterparts. As time wore on, however, the Arsenal’s narrow-gauge rolling stock began to evolve its own characteristics more suited to the heavy usage and dangerous loads that were the order of the day on its railway system. One of the most distinctive features of RAR bogie rolling stock of this type used for the greater part of the railway’s career was the bogie arrangement itself. In order to understand how this came into being, one has to go back to the cast-iron outside-framed four-wheeled ‘turntable’ wagons in use in Chatham Dockyard by 1875 that could also be used as bolsters. By this method, a de facto cast-iron bogie had been created, which must have been a stronger alternative to the wrought-iron fabricated variety also in use on the dockyard’s system at this time. The significance of this development could not have been lost on the Royal Engineers on the Park Railway, for the design of their early gun trolleys for an illustration in the RE Committee Minutes in 1877 shows such a trolley apparently fitted with cast-iron bogies. The 1881 illustration of the Greenwood & Batley four-cylinder compressed air locomotive in the Royal Society of Arts Journal showing the early Arsenal 18in-gauge knifeboard carriage indicates that the latter’s bogies were outside-framed. This illustration is sketchy and likely to be very unreliable, but taken at face value the bogies appear to be timber-framed, unsprung, equipped with cast-iron axleboxes and rubbing irons. Their basic design appears to have been adopted later in modified form as a chassis for some of the four-wheeled hand-pushed wagons. Of course, the 1881 illustration does not provide any evidence of the actual age of the carriage or whether bogie freight vehicles were in use on the Arsenal’s 18in-gauge system at this time (which may by this stage have already been using cast-iron bogies).

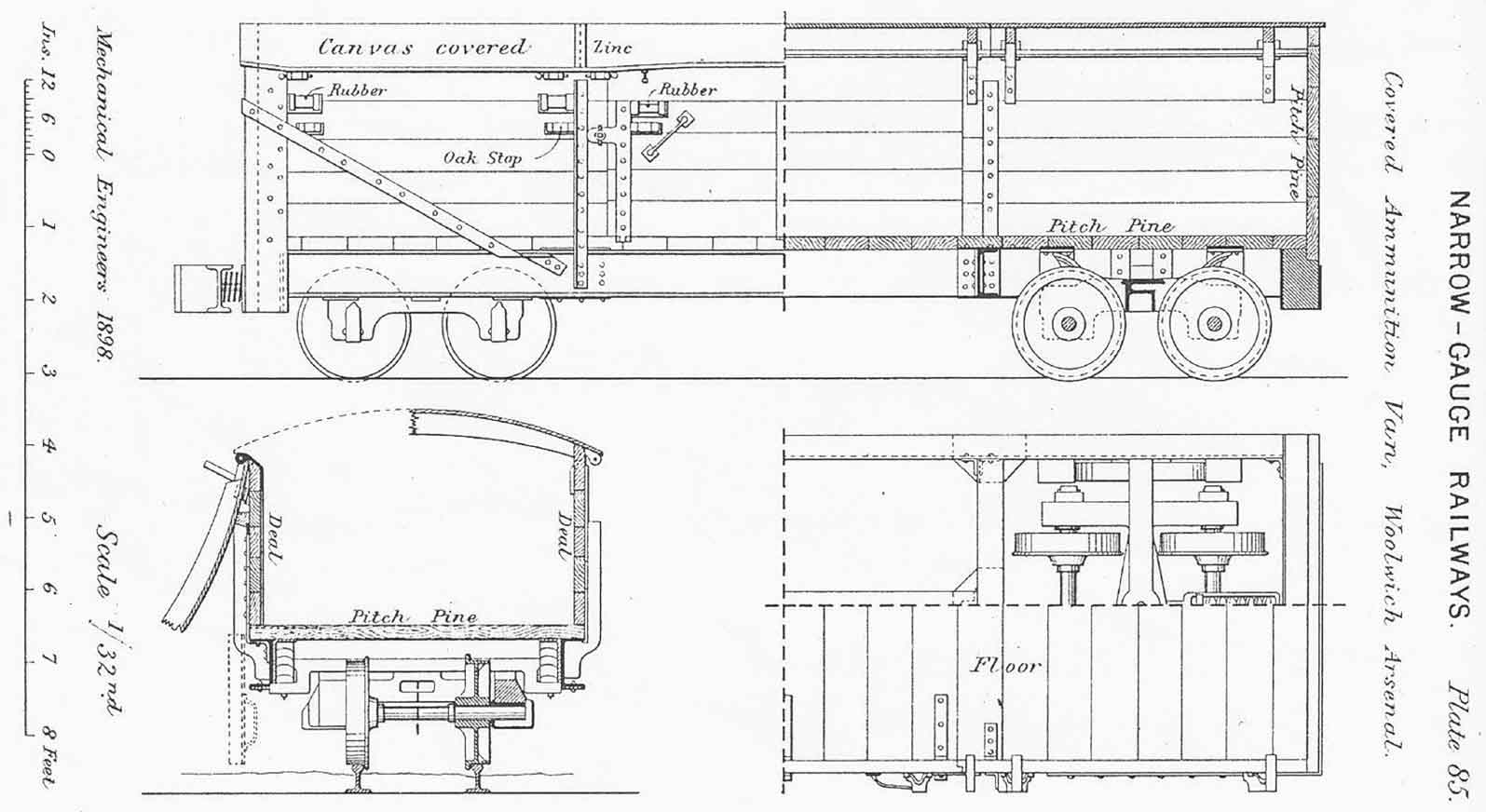

In 1898 Leslie S. Robertson’s paper Narrow Gauge Railways – Two Feet and Under showed a bogie 5-ton ammunition wagon with a bogie design bearing a striking resemblance to that shown in the 1877 RE illustration of its early gun trolley. One important refinement had been introduced during the preceding two decades, however. The bogie design did not readily lend itself to the mounting of suitable suspension and the solution adopted was to have a bogie stretcher with forked ends, each of which was attached to a leaf spring. The ‘fore-and-aft’ ends of each leaf spring were in turn attached to projections fixed to the inner faces of the solebars. This effective ‘flexible mainframe’ arrangement appears to have been unique to the RAR, at least as far as the domestic railway scene was concerned, and was therefore one of its defining characteristics. The Royal Engineers were destined to drop the cast-iron bogie for front-line 18in-gauge use in favour of plate-framed designs during the 1880s, owing to considerations of ease of transportation and the use of Fowler/Decauville portable track of relatively light 24lb/yard specification. The consequence of this decision was that in the latter part of the nineteenth century the RAR had thrust upon it a collection of Fowler and Bagnall wagons with plate-framed bogies originally intended for the Suakin-Berber campaign. These would have required drawgear alterations and appear not to have gained lasting popularity at Woolwich. Some of the Bagnall examples at least accompanied Flamingo, Mars and Venus to Longmoor in 1905. It was to be the bogie wagon chassis design illustrated in Robertson’s work that would dominate locomotive-hauled wagon practice for the remainder of 18in-gauge operation. The 5-ton covered ammunition wagon was soon developed into a 7-ton version (which was constructed both in-house and by outside contractors), while the chassis design was also used as a basis for single plank wagons, hay wagons, timber wagons and, after the development of an even stronger bogie, wagons for conveying heavier traffic.

One of the earliest established features in widespread adoption on the Arsenal’s 18in-gauge rolling stock was the cast-iron bogie. Close examination of this 1877 illustration of an early gun trolley in the RE Committee Minutes shows that prior to the introduction of the Greig/Decauville pattern of portable track into RE practice, bogies of similar pattern were in use at the School of Military Engineering in Chatham. It may even be that these bogies were manufactured at the Arsenal and supplied to the Royal Engineers, although this cannot now be proved. (RE Committee Minutes)

By 1898, the standard bogie goods vehicle associated with the Royal Arsenal Railways was well on the way to its final stage of evolution as shown by the drawing of this five-plank covered ammunition wagon illustrated in Leslie S. Robertson’s paper. The channel-framed steel chassis is now very much in evidence, as are the spring-loaded bogie stretchers that formed the suspension arrangements (which would also have been found on the composite carriages and superintendent saloon). Other features of note are the pitch pine floor and end planks, deal side planks and canvas-covered zinc roof. The standard chassis design had therefore become established and it only remained for the body to be enlarged for the final state of development to be reached. (Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers)

Many four-wheeled 18in-gauge wagons were designed solely for hand propulsion within factory confines and these included the simple platform variety for the conveyance of cartridge boxes and enclosed ‘red’ ammunition wagons (one of which survived as late as May 1970 but was subsequently destroyed). These were typically of timber construction with cast-iron axleboxes and had buffers formed simply as extensions of the solebars. Other four-wheeled wagons were fitted with the standard form of buffers and drawgear for locomotive haulage. Examples included coal trucks, ash trucks, shipping trucks and red ammunition wagons. Some of these had all-steel channel-framed chassis but others had timber solebars with cast-iron axle bearings arranged on each side as single castings for both axles. Shipping trucks (with detachable ‘tops’ fitted with eyes to allow for carriage aboard ships) were constructed to this latter specification (of a design similar to that used from 1915 by the Royal Army Service Corps at Deptford), as were ammunition wagons.

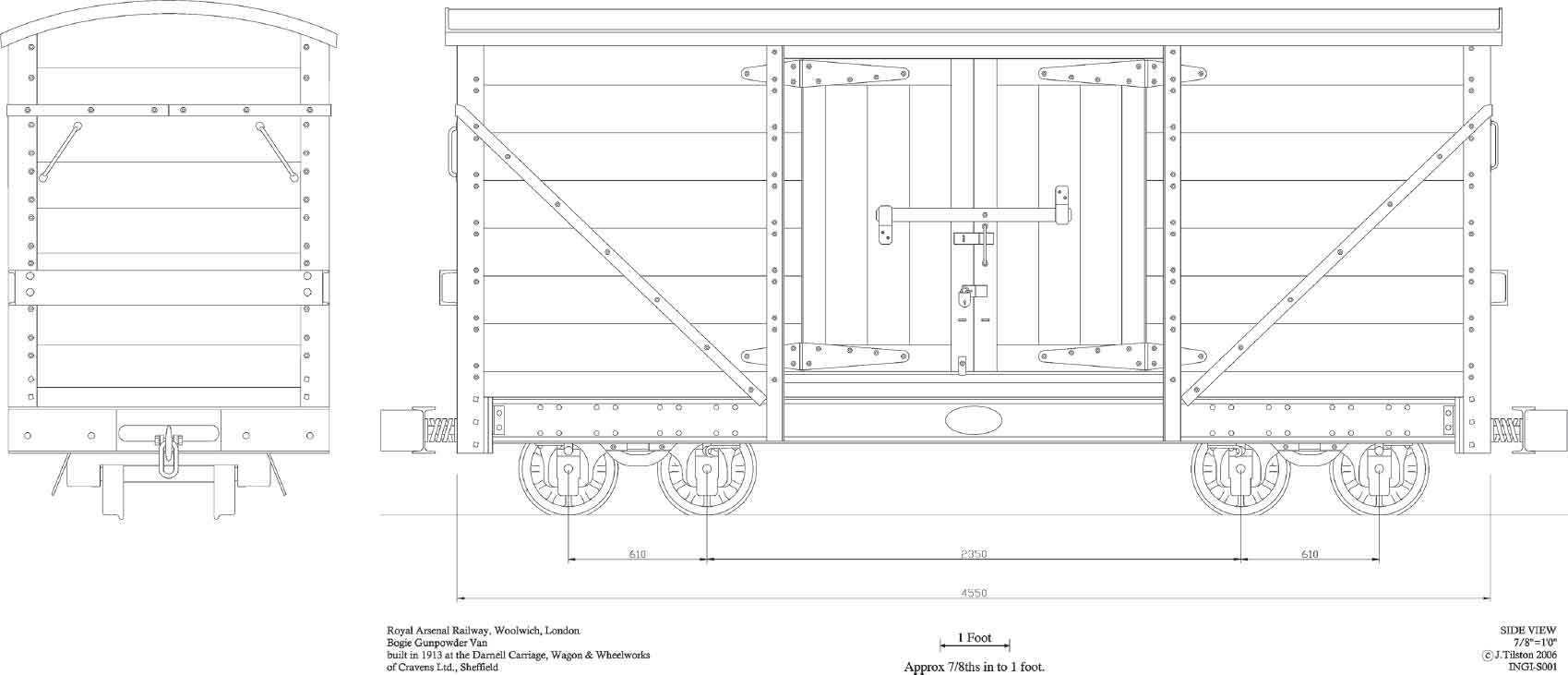

The mainstay of the RAR 18in-gauge rolling stock fleet after the post-First World War rundown of much of the equipment of this gauge was the 7-ton bogie ammunition wagon. Developed from the earlier 5-ton vehicle (and using a similar chassis design) during the 1899–1902 Second Boer War, many of these wagons were constructed both in-house and by external contractors during the build-up to the 1914–18 conflict, with some examples remaining in use until the 1960s. The higher body sides necessitated by the increase in capacity over their precursors is evident in both side and end views. These drawings were made using measurements taken from the only complete surviving example. (J. Tilson)

For the conveyance of third-class passengers on the 18in-gauge system, the knifeboard carriage remained the norm until 1916. The design shown in the 1881 illustration was developed during the late 1880s or 1890s into a more robust form utilizing the standard cast-iron bogie. The ‘passenger accommodation’ was constructed from three longitudinal timbers, the central plank constituting the lower backrest with two identical narrower flanking timbers laid flat and forming the seats. A lower pair of structural longitudinal timbers formed the solebars and at each end of the vehicle, a pair of fabricated ‘U’-irons (one each side) was attached to the lower and possibly inner surface of the solebars. To these were attached the bogie stretchers which appear in design to have predated the ‘flexible’ pattern utilized by the time of Robertson’s work. These vehicles, therefore, appear not to have possessed any form of springing. Iron stiffening members were fitted in various places, including soleplates and stays between the lower part of the central stretcher and the upper outer ends of the backrest. This latter arrangement must have caused considerable discomfort to the passengers seated at the extreme ends of the carriage, given that the stays encroached upon the sitting area in these parts of the vehicle. Despite the provision of footboards, an upper backrest and rudimentary iron arm-rests at each end, there was very little concession to passenger comfort generally in the design of these vehicles and the 1914–18 Chief Mechanical Engineer’s Report recorded that by the end of their careers many complaints had been made about them, even in the local press. There was no protection from the rain and when such weather prevailed, the seats were invariably very wet. The length of these carriages appears to have been 25ft over headstocks, width approximately 5ft 8in over footboards and composite buffers were employed, albeit rigidly mounted.

The four-wheel ammunition van remained in use on the 18in gauge for specialist locomotive-hauled applications with one example surviving to the present day. Side and end elevations are shown in the upper two views. This example uses a chassis design similar to the shipping trucks (with detachable open bodies) utilized both on the RAR and, in modified form, on the Royal Army Service Corps system from 1915 onwards in the old Foreign Cattle Market at Deptford. (J. Tilson)

This view shows a selection of RAR 18in-gauge rolling stock, both bogie and four-wheel, c.1920. Nearest the camera can be seen one of the shipping trucks with the detachable body bearing a different number to the chassis. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

One of the early knifeboards is seen here apparently after withdrawal from service following the arrival of the ‘toast racks’ in 1916. Open to the elements, apparently unsprung and with part of the seating area taken up by tie-rods, they must have been extremely uncomfortable vehicles in which to travel. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

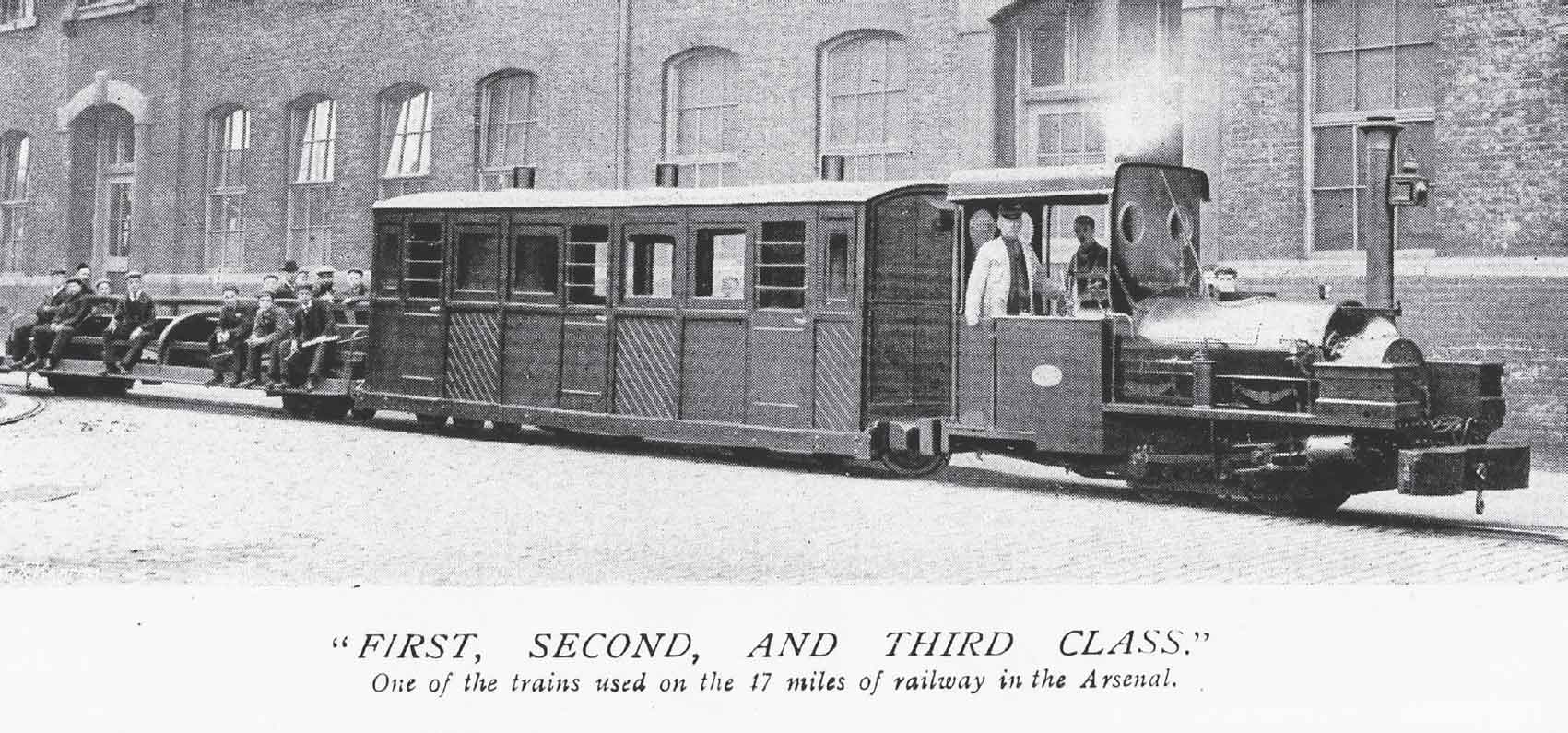

Bogie narrow-gauge passenger vehicles designed specifically for officers and dignitaries had made their appearance on the RAR system by the late 1890s and detailed examination of the surviving illustrations certainly pays dividends when the researcher is attempting to piece together the story of their evolution. In The Navy and Army Illustrated a photograph entitled ‘First, Second and Third Class’ shows the Manning Wardle locomotive Arquebus, one of the third-class vehicles described in the previous paragraph, and what is presumably a first/second three-compartment ‘composite’ carriage. For reasons mentioned in the accompanying caption, there is strong evidence to suggest that this carriage was originally constructed by the Royal Engineers for the Borstal Railway at Chatham, probably during the 1880s (rolling stock bodies are known to have been constructed in similar fashion for use on the 2ft 6in gauge part of the Chattenden & Upnor system at the same time), and transferred a decade or so later to the RAR. It would have seated sixteen passengers: six in the first-class end compartments and ten in the second-class central compartment. It is not known precisely how many carriages of this design saw service on the RAR, but at least one was still extant in March 1918 when it was filmed in use. Exact dimensions are difficult to estimate from photographs, but the length over headstocks would have been in the region of 21ft while the overall width would have been approximately 5ft 8in.

This photograph was first published in The Navy and Army Illustrated in 1899 and it shows an early-pattern first/second composite bogie coach together with one of the third-class open ‘knifeboards’. The latter vehicle is clearly developed from the bogie knifeboard carriage shown among the Chatham Dockyard vehicles in Engineering in 1875, but it appears to have been of more substantial construction and utilized the standard pattern of cast-iron bogie preferred by the Arsenal authorities. The composite vehicle has three compartments (with associated lamp arrangements) and the size ratio of the compartments would lead one to suspect that the two end compartments were for first-class passengers with the second-class seats occupying the central compartment. Other features of interest are the barred windows on the doors and the arrangement of the diagonal planking for the body panels. The bogies would once again appear to be of the standard cast-iron pattern (possibly substituted by the Arsenal for earlier plate-framed ones), while two observations would suggest that the carriage was built by the Royal Engineers rather than being supplied by an external contractor. The first of these is the shape of the non-door window frames, with their radiused corners (as found on other Arsenal-built carriages), while the second is the apparent lack of any maker’s plates. The doors were, in all probability, fitted with droplights. The composite carriage would appear to have been relatively new when the photograph was taken, and certain constructional features suggest that it may have originally been built for use on the Medway Borstal line and later modified for use on the Arsenal’s railway system. (The Navy and Army Illustrated)

During the late 1890s a ‘house style’ began to evolve for 18in bogie vehicles constructed by the Royal Carriage Department for use on the RAR. Surviving illustrations show a design of vehicle characterized by its timber-framed chassis with iron soleplates, standard bogies, saloon configuration with seating (apparently) for fourteen passengers, ornate moulded panelling, louvred door vents and a roof design that appeared to owe much in its inspiration to the pattern found on the Spooner bogie luggage vans of the Ffestiniog Railway. A new pattern of rigid metal buffer was employed and close inspection of the underframe reveals some interesting constructional details. At each end of each solebar can be seen two pairs of four bolts arranged in a small, almost square, rectangle. In the centre of each of these pairs can be seen another ‘rectangle’ of four bolts, of the same height as the others, but more elongated in configuration. These bolts secured the slides on the inner faces of the solebars for the central spring buckles, while each flanking pair of four bolts supported the anchorages for the springs to the solebars. The two fore and aft pairs of spring anchorages would, by reason of their positions, also have acted as bracing for the bufferbeams. These latter components were each enclosed by the lower part of their adjacent end body panelling. Four more bolts, arranged as a pair of ‘singles’ located each side of the door, appear to have been associated with angle-iron bracing for timber frame stretchers and (possibly) supporting iron stays. Another significant design feature of the solebars was apparent from the fact that they overhung the body at each end by approximately 5 inches. The body of the vehicle would have been approximately 5ft 9in wide between the vertical portions of the sides and 15ft long with a roof overhang all round of approximately 3 inches, with a total height from rail to roof of approximately 8ft 6in.

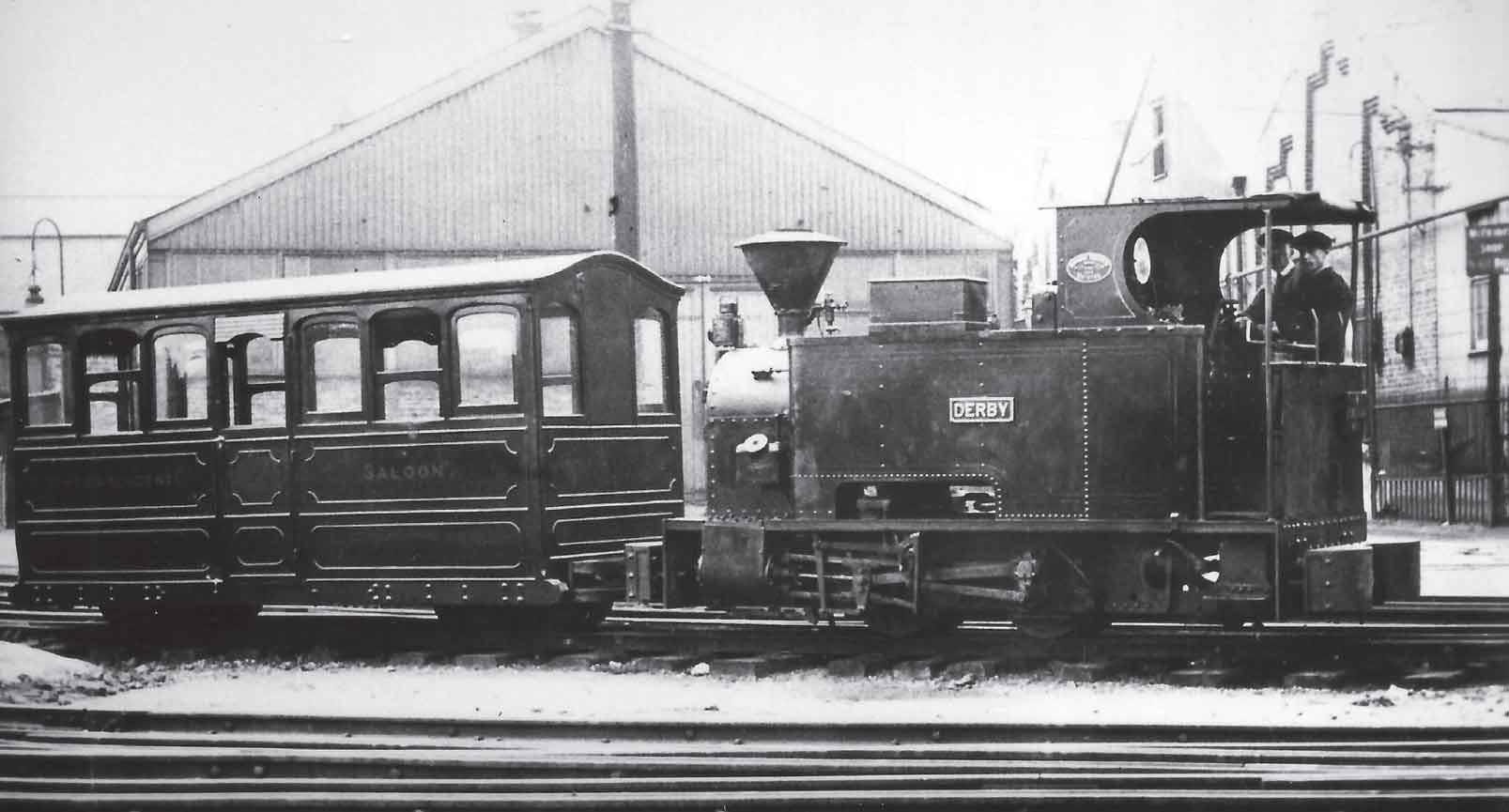

The superintendent saloon was an attractive and distinctive vehicle that seems to date from c.1900, apparently constructed for the use of the superintendent of building works. Its general body styling appears to have looked forward to the successor of the composite carriage design shown in the picture with Arquebus in that the diagonal planking has been dispensed with in favour of a much smoother outline, in this case embellished with reverse-radius cornered panels. Close inspection of the body shape reveals that in line with contemporary mainline practice, it possessed pronounced inward tapers at its lower sides to meet the underframe. Its backward-looking features included a roof apparently inspired by Charles Spooner’s ‘curly roof’ luggage vans of the 1870s and the retention of iron or steel-faced timber solebars. The bogies were once again of the standard pattern, while the composite buffers were of a non-standard narrower pattern requiring full-width slots for the drawbars (in order to clear the endward projecting solebars). Two droplights and a door ventilator were provided on each side, while an additional droplight was provided in the centre of one end. The saloon is seen here with Avonside 0-4-0T Derby in the spring of 1921. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

Following the commencement of the 1899 South African conflict, further bogie carriages were constructed by the Royal Carriage Department to accompany the six Kerr, Stuart 0-4-0STs of 1901. Certain design features present in the ‘saloons’ referred to in the previous paragraph also found their way into these vehicles, but certain improvements were made in the light of experience gained with the earlier items of rolling stock. Unlike the saloons, the new carriages were first/second-class ‘composites’ (fourteen seats first-class and eighteen second-class) with steel channel frames sitting at low level so as to almost totally obscure the bogies from view. The normal RAR-pattern bogies and flexible bogie stretcher arrangement were used and this necessitated upwardly-projecting spring buckle slides and spring mountings from the inner faces of the solebars to cater for the low pitch of the solebars. In turn, this constructional arrangement dictated the need for a raised floor within the carriage body so as to clear the bogies and springing. The general shape of the body was recognizably similar to that of the saloons, with its (albeit simplified) panelling and ‘soft’ corners, and the use of louvred ventilation was extended from the doors only to the windows as well. This level of ventilation was apparently not considered adequate and five ‘torpedo’ roof vents were also provided, two for first-class and three for second. Each compartment was accessed by a pair of doors (one on each side) and the roof, unlike that of the saloon design, was of conventional profile, but of similar construction. The dimensions recorded for the ‘standard composites’, as these carriages may be termed, in The Locomotive in 1921 were 24ft long over headstocks and 6ft wide; presumably this latter dimension referred to the vertical parts of the carriage sides. The width over the roof would have been approximately 6ft 6in.

At the end of the nineteenth century, gun barrels in excess of 100 tons had become the order of the day and more substantial wagons were constructed to replace the early timber-framed gun trucks that had seen service on the Arsenal’s railway system. A diagram survives, apparently a copy of RAR 173 (it is not known whether this was a diagram or vehicle number), showing a double-truck arrangement for the conveyance of a 120-ton gun on four bogies capable of negotiating 60ft radius curves. No date appears on the drawing, but the use of composite buffers indicates that it dates from the late 1890s. It is not known whether any vehicles were actually constructed to this design, which would have required a ‘spacer’ truck to allow haulage from the muzzle end, but in view of later developments the design does not appear to have been a success. During the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, the products of Leeds Forge were to prove popular with the War Department and examples of the company’s products were to be found on the Chattenden & Upnor line (of similar pattern to the 2ft 6in-gauge vehicles supplied to the Barsi Light Railway in India) and later on the Longmoor Military Railway. Leeds Forge products typically employed channel iron solebars and Fox’s Patent pressed steel outside-framed bogies. Sadly the one drawing that has come to light, that of a wagon for a 30-ton gun barrel, is incomplete and shows only the solebar assembly and the gun cradle arrangement, there being no buffer or bogie detail. It is clear from the surviving evidence, however, that the South African conflict of 1899–1902 had ushered in the era of gun barrel wagons being constructed by outside contractors in a comparably substantial fashion to the proof sleighs, whose provision appears to have remained an in-house responsibility. These developments in vehicles for gun transportation were also mirrored on the military railway at Shoeburyness during the same period.

As had been the case with the locomotives, there was a programme of acquisition of new items of rolling stock during the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War. During the year ending March 1912, 57 items of narrow gauge rolling stock were made in the Arsenal’s Rolling Stock Shop, with corresponding totals of 53 and 26 being recorded for the years ending March 1913 and 1914 respectively. Out of this grand total of 136, 33 were recorded as eight-wheeled ammunition trucks. The records are sadly incomplete as it is known from surviving artefacts that further eight-wheeled ammunition trucks were supplied during the same period by Cravens of Sheffield. During the same period, further purpose-built standard-gauge rolling stock was supplied. Apart from one flat-topped truck supplied by Leeds Forge, all these items were constructed by Hurst Nelson of Motherwell and comprised 2 cradle trucks, 9 ballast trucks, 18 low shot trucks, 2 tube trucks and 3 gun trucks. According to information provided by the 1914–18 CME Report, there were approximately 333 standard-gauge and 1,163 narrow-gauge items of rolling stock in use at the beginning of the First World War. During the period of the conflict, as evidenced by the November 1918 totals, 400 items of standard-gauge rolling stock were to be acquired (64 new and 336 second-hand) and 381 narrow-gauge items (all new). Although the detailed data relating to rolling stock construction by the MED refers to the construction of four flat-topped standard-gauge trollies during 1914, these are not mentioned in the CME report table covering rolling stock acquisition for 1914–18. Sadly no data survives regarding scrapping of rolling stock during this period, but it is known that a significant number of withdrawals did take place. The MED Report for the year ending March 1919 recorded that several old and obsolete trucks had accumulated in the rolling stock shop sidings during the wartime period and that these were finally being broken up.

Of the notable items of rolling stock acquired during the conflict, one group fulfilled a particular need, namely the replacement of the Suakin bogie coaches on the standard-gauge passenger service. At some stage during 1915, three four-wheeled carriages were purchased from the SE&CR with eleven similar vehicles following suit in 1916. In addition, two ex-SE&CR six-wheeled vehicles were acquired and converted into eight-stretcher ambulances in 1916, with one believed to have been constructed as a mail van, and this latter vehicle was fitted with special ‘Warner’-pattern fore and aft wheelset bearings in order to facilitate negotiation of a 75ft radius curve close to the carriage inspection shed. It is known that in addition to the Suakin bogie carriages, four standard-gauge four-wheelers were in use prior to 1915 and, given the total of eighteen four-wheelers recorded in service in 1917, the obvious inference is that all four such carriages in use pre-1915 remained in use at that stage. Given the previously noted survival of two Suakin four-wheelers as service vehicles during the Second World War, it is highly probable that all four pre-1915 four-wheelers were originally built for the Suakin-Berber campaign. Second-hand four-wheeled standard-gauge wagons, mainly of the ballast and open goods variety, were acquired from various sources including contractors such as Pauling & Co., dealers such as John F. Wake, and railway companies such as the Great Eastern, the London and South Western and the North Staffordshire. It was even necessary to resort to the hire of fifty open goods ‘Red Dock’ wagons from the North Eastern Railway in 1916 at a cost of 6/- per week per wagon (this measure was undertaken, significantly, during the ‘Raven’ period); however, this was reduced to 5/- in September 1916. The Army Ordnance Department retained some fourteen secondhand standard-gauge wagons in Woolwich Dockyard at the outbreak of the conflict and these were taken into RAR stock proper during 1915.

This 1914 view of a Hurst Nelson gun truck illustrates the overall proportions of the vehicle’s design. A Weight Diagram of RAR Gun Truck No. 1113 (MED Drawing 2292/41) probably dating from the same year gives more details of the basic arrangement of these vehicles for handling gun barrels of 110 tons or thereabouts constructed just prior to and during the First World War (the design was nominally designated 100 tons). The axle loading was kept to 13.5 tons by means of the design shown. Essentially the vehicle consisted of three permanently coupled trucks, each supported by two fourwheeled bogies, with an articulated breech support platform and a pedestal barrel support (mounted on the ‘third’ truck). Although photographic evidence shows that drawgear was fitted at both ends of the vehicle, this is only shown at the breech end on the diagram, suggesting that normal practice was to haul the loaded truck from this end. Haulage in such circumstances from the barrel end would have required an intermediate ‘spacer’ truck. The diagram also refers to the fact that the phosphor bronze bearings and associated lubricating pads were earlier designs dating from 1907–11 and were probably standard with other Hurst Nelson vehicles of this period. Two vehicles of this type were supplied to the Arsenal in November 1913, a third in January 1914 and three more during 1917. The bogies are of pressed steel construction, a principle introduced into RAR practice by Leeds Forge Co. Ltd and also used during the years immediately spanning the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries on the Chattenden & Upnor Railway (2ft 6in gauge) and at Shoeburyness and Longmoor. (Greenwich Heritage Centre)

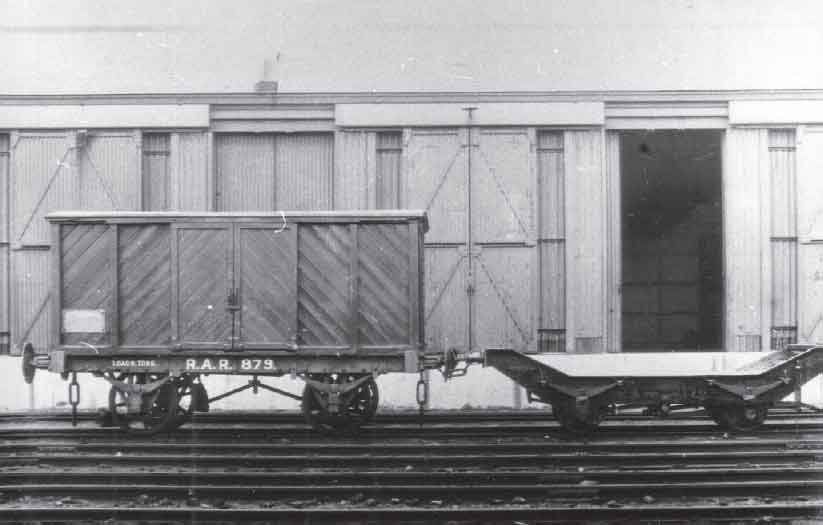

Two standard-gauge wagons are illustrated here. On the left is an 8-ton ammunition wagon, while on the right is a low shot wagon. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

No. 1207 in the RAR Rolling Stock Register was this 20-ton bogie tube wagon. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

The purchase of new standard-gauge rolling stock continued during the conflict, with Hurst Nelson making a major contribution in the form of seven four-wheeled ammunition wagons in 1915, four 8-ton timber wagons in 1916 and, in the following year, three examples of this supplier’s piéce de résistance, the six-bogie truck capable of handling guns of 100 tons. Other suppliers included Midland Carriage and Wagon Co. (six four-wheeled low shot wagons in 1916), C. Roberts (two bogie 30-ton gun trucks in 1916), and Cravens of Sheffield (thirty-five four-wheeled 10-ton timber wagons and three bogie 20-ton gun trucks in 1917). Raven’s influence made its presence felt once again with the supply of four bogie cradle wagons by the North Eastern Railway in 1916.

The RAR possessed four standard-gauge rail ambulances at the time of the 1918 Armistice. One survivor remained to be mentioned in The Locomotive in 1921 and it was numbered 696 in the RAR series. The feature claimed that by 1921 it was seldom used as cases of serious injury involving single victims were dealt with by motor ambulance by that stage. Despite the assertions made in The Locomotive, this vehicle was one of two purchased from the SE&CR in 1916 and converted into an eight-stretcher ambulance by the Arsenal in that year. Although claimed to have been constructed as a third-class carriage, it was most likely to have begun life as a mail van. In order to negotiate the 75ft-radius curve found near the carriage inspection shed, this vehicle was fitted with ‘Warner’-pattern swivelling trucks on the first and third axles, giving properties similar to Bissell trucks and a chassis with effectively no fixed wheelbase. This would surely have resulted in a rather bumpy ride, especially if an emergency necessitated travel at any significant speed. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

Since RAR 18in-gauge rolling stock design had evolved its major distinctive characteristics well before the outbreak of the First World War, all subsequent additions were destined to be new rather than secondhand. The opening months of the conflict, up to the end of 1914, saw the construction of twenty-five timber wagons in the MED’s rolling stock shop (these were authorized as early as March 1914), and the purchase of forty-five ballast wagons from Harrison & Camm. This pattern of part in-house construction and part external purchase was to continue in 1915 with 248 further wagons comprising the following: flat top (30 Harrison & Camm); cradle (10 MED, 22 Harrison & Camm, 8 Cravens); shipping trays (100 Harrison & Camm); ballast (20 MED, 25 Cravens), and ammunition (33 Cravens). In 1916 all new 18in-gauge wagons were constructed in-house by the MED and comprised a single ammunition wagon, six pan wagons and eleven flat tops. Some eighteen further flat tops were built by the MED in 1918, but an external supplier had to be resorted to in the form of G.R. Turner during the same year to supply twenty coal wagons for the RAR’s 18in-gauge network. The data given in the table detailing all these items is slightly at variance with that recorded for the breakdown of narrow-gauge wagons constructed by the MED during the same period, which gives a total of ninety-eight new vehicles as opposed to ninety-one for the former.

The year 1916 saw one additional narrow-gauge rolling stock event of significance as the decision had at last been taken to pay heed to complaints about the early third-class carriages. The 1914–18 CME’s Report records that owing to the anticipated difficulty (due to the potential for instability) in arriving at a suitable design for a covered 18in-gauge passenger vehicle, Bristol Carriage and Wagon Co. were invited to send representatives to the Arsenal to witness experiments with some of the Arsenal’s existing rolling stock. It has to be remembered that this was the first (and last) occasion on which an external contractor was called upon to build passenger vehicles to satisfy the Arsenal’s narrow-gauge requirements and none of the other major home-based 18in-gauge military service railways of the period – Deptford (RASC), Chatham Dockyard and Waltham Abbey – are known to have possessed externally-supplied passenger vehicles. The Borstal system is known to have possessed bogie convict carriages introduced by Lancaster Wagon Co. in the early 1880s, but these were long gone by 1916 and in any case were somewhat narrower than the vehicles required by (and eventually supplied to) the RAR. Surviving evidence shows that Bristol C&W Co. made at least two attempts to design a carriage to fulfil the requirements of the RAR. Drawing No. 10686, dated 5 April 1916, shows a forty-seat five-compartment ‘toast rack’ vehicle with a length over headstocks of 24ft 6in and a distance between bogie pivots of 16ft. The buffers were of the later (apparently sprung) composite variety and it appears that the rationale behind this proposal (negotiation of the tightest possible curve for a bogie carriage of the given dimensions and ‘wagon pattern’ drawgear) was to allow the carriage to operate as close as possible to any given factory (presumably the RAR timetables and working patterns would have had to have been altered to suit). In any event, Drawing No. 10691, dated 22 May 1916, was adopted. This shows a revised forty-seat ‘toast rack’ measuring 25ft over headstocks and 6ft 3in wide over footboards, with a distance between bogie pivots of 20ft 4in and an overall height of approximately 8ft 6in. The buffers were of the single ‘radial’ steel pattern found on most of the existing covered narrow-gauge passenger carriages. The superstructure (roof, body, seats and upper solebars) was of timber construction, while the underframe was a combination of steel frame and angle and the standard pattern of cast-iron bogie was employed (Drawing No. 10697). The design of this item was revised from January 1916 onwards in order to reduce the number of breakages experienced during ordinary service, and the MED Report stated that some 300 of these bogies had been obtained from external suppliers. It is not clear whether this total included those already fitted to new vehicles or whether they were all supplied separately as spares.

Following long-standing complaints about the comfort and safety of the early knifeboard bogie workmen’s cars, experiments were undertaken during the First World War to arrive at a design for a more practical replacement. One proposal utilizing a relatively short dimension of 16ft between bogie pivots and standard non-passenger buffers was rejected in favour of this final ‘toast rack’ design with 20ft 4in between bogie pivots, 25ft length over headstocks and 27ft 4in overall length. Seven vehicles were constructed in 1916; four were initially covered and three open. During their career on the RAR the latter three were equipped with roofs and all were eventually equipped with brakes and side enclosures. The diagrams show the side and end views (part sectional), the half plan of the chassis and the part sectional views of the bogie frames. (Author)

Seven new 18in-gauge bogie ‘toast racks’ were delivered from Bristol C&W Co. in 1916 and, rather surprisingly in the light of previous experience, only three were built with roofs. The 1914–18 CME’s Report records that by the end of the conflict, roofs had been fitted to the erstwhile ‘opens’ and further protection from the weather was provided by fitting part sides to the compartments of the vehicles. No brakes were fitted when these carriages were delivered, but the longer and heavier passenger trains necessitated by the war ensured that the braking power of the engine alone was insufficient. Owing to space limitations and the design of the bogies, designing suitable brakes for the new third-class carriages was not easy but was eventually accomplished. These handbrakes were operated by the train conductors.

The rolling stock shop was kept busy throughout the First World War with undertaking the necessary repairs to keep the RAR’s rolling stock fleet in working order. In all, some 1,256 repairs to standard-gauge vehicles (freight and passenger) were undertaken during the period of the conflict, with the peak of 389 being reached during the year from 1 April 1917 to 31 March 1918. The corresponding grand total for narrow-gauge repairs was 4,849, with the annual peak of 1,370 being reached during the year 1 April 1916 to 31 March 1917. The mention of both narrow- and standard-gauge divider trucks in the relevant tables shows that the remaining Hornsby locomotives did make some contribution to traffic requirements throughout the war, although this would have tailed off sharply towards the end. No data was given relating to the repair of proof sleighs, even though a later Royal Arsenal map of Second World War vintage shows a servicing pit for these vehicles. Other work undertaken by the rolling stock shop during the conflict included construction of trailers for road tractors and sundry carpentry, such as the manufacture of trolleys and hand carts. The number of staff employed in the rolling stock shop rose from 37 to 63 between August 1914 and November 1918, with the number of carpenters rising from 22 to 29 during the same period.

The MED Report for the year ending 31 March 1919 reveals further details relating to the use of rolling stock during the latter period of the First World War and the early months following the Armistice. The copper shortage that had prompted the use of steel boiler tubes in some of the steam locomotives also persuaded the MED to substitute white metal bearings for brass on some of the 18in-gauge vehicles, although this practice was discontinued after the copper shortage had eased (despite the fact that the white metal bearings had proved satisfactory in service). By March 1919, there was little difference in cost between the two types. Thought was given to the possibility of fitting roller bearings to the cast-iron narrow-gauge bogies (which could not have been accomplished without major modification to the design of the bogie frames). The possibility was also envisaged of adopting lighter pressed steel bogies on the narrow gauge but, given the general rundown that was to follow the Armistice, this was never to happen. Approval had also been given to convert the two redundant American bogie underframes to gun trucks as had already been done with one of their number, but it was not certain by March 1919 that the conversions would be required and they were postponed. Once again, given the prevailing economic climate, it seems certain that this was never carried out. It was also felt, given the wartime success of the motor ambulance, that at least two of the standard-gauge ambulance cars could be disposed of (the 18in-gauge ones having apparently disappeared by this stage). In the meantime, given the cost of painting these vehicles white at fairly frequent intervals, it was felt that maintenance on all of them should be reduced to the necessary minimum. Consideration had been given to the fitting of continuous braking to the standard-gauge passenger train but as has been noted, it was not felt to be cost-effective, given that each passenger train had the braking power of the locomotive and two brake vans.

Avonside locomotive Sheffield is shown here with four-coach ‘Passenger Train No. 1’ (as proclaimed by the Duty Board) consisting of two ‘turn-of-the-century’ first/second-class composites and two Bristol Carriage & Wagon Co. third-class ‘toast racks’. This photograph was used in The Locomotive and probably dated from 1918. (The Late Major Taylorson Collection via John Townsend)

Whatever major reforms to rolling stock policy may have been envisaged at the time of the Armistice, relatively few constructive measures were destined to be taken during the interwar years owing to more general economic and political factors prevalent during that period. The shift in the balance of power in favour of the standard gauge was reflected in the disposal of the remaining 18in-gauge passenger vehicles following their withdrawal from service and the advertisement in Machinery Market of 13 January 1933 referring to 400 trucks, all apparently of 18in gauge, has already been mentioned in Chapter Seven. Owing to their description as ‘trucks’, not all these items may have been wagons fitted with drawgear for routine operation on the RAR and some at least may simply have been hand-pushed four-wheeled ‘factory’ vehicles. Whatever their design and purpose, they were not, unlike their accompanying locomotives, mentioned in the Cohen advertisement of the following March and it would appear that they were broken up for any salvageable scrap metal at Canning Town in the early part of 1933.

The Second World War period was characterized by the final stage in the development of proof sleighs and photographic evidence shows that new sleighs were constructed during this period. The carriages then in use on the passenger service were showing their age and it was decided to purchase some newer fourwheeled ex-L&NWR vehicles, originally constructed for use on the North London Railway shortly prior to this line’s electrification, c.1940. These items bore the brunt of the RAR’s passenger requirements during the remainder of the system’s existence.

Details of the reduction in the rolling stock fleet during the final two decades of the RAR’s existence are sketchy, but Appendix I shows that the Universal Directory of Railway Officials & Railway Year Book reported rolling stock numbers between the years 1947 and 1955. The total remained steady at 1,600 vehicles (presumably an approximate figure) for most of this period until 1953 when it dropped to 1,500. Sadly no breakdown is given between standard and 18in gauge, or between passenger, freight and ‘specialist’ vehicles such as proof sleighs, but these latter items would have fallen out of use during the 1950s with the eclipse of long-range artillery.