Book IV.

Terror.

Chapter I.

Charlotte Corday.

In the leafy months of June and July, several French Departments germinate a set of rebellious paper-leaves, named Proclamations, Resolutions, Journals, or Diurnals ‘of the Union for Resistance to Oppression.’ In particular, the Town of Caen, in Calvados, sees its paper-leaf of Bulletin de Caen suddenly bud, suddenly establish itself as Newspaper there; under the Editorship of Girondin National Representatives!

For among the proscribed Girondins are certain of a more desperate humour. Some, as Vergniaud, Valazé, Gensonné, ‘arrested in their own houses,’ will await with stoical resignation what the issue may be. Some, as Brissot, Rabaut, will take to flight, to concealment; which, as the Paris Barriers are opened again in a day or two, is not yet difficult. But others there are who will rush, with Buzot, to Calvados; or far over France, to Lyons, Toulon, Nantes and elsewhither, and then rendezvous at Caen: to awaken as with war-trumpet* the respectable Departments; and strike down an anarchic Mountain Faction; at least not yield without a stroke at it. Of this latter temper we count some score or more, of the Arrested, and of the Not-yet-arrested: a Buzot, a Barbaroux, Louvet, Guadet, Pétion, who have escaped from Arrestment in their own homes; a Salles, a Pythagorean Valadi, a Duchâtel, the Duchâtel that came in blanket and nightcap to vote for the life of Louis, who have escaped from danger and likelihood of Arrestment. These, to the number at one time of Twenty-seven, do accordingly lodge here, at the ‘Intendance, or Departmental Mansion,’ of the town of Caen in Calvados; welcomed by Persons in Authority; welcomed and defrayed, having no money of their own. And the Bulletin de Caen comes forth, with the most animating paragraphs: How the Bourdeaux Department, the Lyons Department, this Department after the other is declaring itself; sixty, or say sixty-nine, or seventy-two1 respectable Departments either declaring, or ready to declare. Nay Marseilles, it seems, will march on Paris by itself, if need be. So has Marseilles Town said, That she will march. But on the other hand, that Montélimart Town has said, No thoroughfare; and means even to ‘bury herself’ under her own stone and mortar first,—of this be no mention in Bulletin de Caen.

Such animating paragraphs we read in this new Newspaper; and fervours and eloquent sarcasm: tirades against the Mountain, from the pen of Deputy Salles; which resemble, say friends, Pascal’s Provincials. What is more to the purpose, these Girondins have got a General in chief, one Wimpfen, formerly under Dumouriez; also a secondary questionable General Puisaye, and others; and are doing their best to raise a force for war. National Volunteers, whosoever is of right heart:* gather in, ye National Volunteers, friends of Liberty; from our Calvados Townships, from the Eure, from Brittany, from far and near: forward to Paris, and extinguish Anarchy! Thus at Caen, in the early July days, there is a drumming and parading, a perorating and consulting: Staff and Army; Council; Club of Carabots, Anti-jacobin friends of Freedom, to denounce atrocious Marat. With all which, and the editing of Bulletins, a National Representative has his hands full.

At Caen it is most animated; and, as one hopes, more or less animated in the ‘Seventy-two Departments that adhere to us.’ And in a France begirt with Cimmerian invading Coalitions, and torn with an internal La Vendée, this is the conclusion we have arrived at: To put down Anarchy by Civil War! Durum et durum, the Proverb says, non faciunt murum.* La Vendée burns: Santerre can do nothing there; he may return home and brew beer. Cimmerian bombshells fly all along the North. That Siege of Mentz is become famed;—lovers of the Picturesque (as Goethe will testify*), washed country-people of both sexes, stroll thither on Sundays, to see the artillery work and counterwork; ‘you only duck a little while the shot whizzes past.’1 Condé is capitulating to the Austrians; Royal Highness of York, these several weeks, fiercely batters Valenciennes. For, alas, our fortified Camp of Famars was stormed; General Dampierre was killed; General Custine was blamed,—and indeed is now come to Paris to give ‘explanations.’

Against all which the Mountain and atrocious Marat must even make head as they can. They, anarchic Convention as they are, publish Decrees, expostulatory, explanatory, yet not without severity; they ray forth Commissioners, singly or in pairs, the olive-branch in one hand, yet the sword in the other. Commissioners come even to Caen; but without effect. Mathematical Romme, and Prieur named of the Côte d’Or, venturing thither, with their olive and sword, are packed into prison: there may Romme lie, under lock and key, ‘for fifty days;’ and meditate his New Calendar, if he please. Cimmeria, La Vendée, and Civil War! Never was Republic One and Indivisible at a lower ebb.—

Amid which dim ferment of Caen and the World, History specially notices one thing: in the lobby of the Mansion de l’Intendance, where busy Deputies are coming and going, a young Lady with an aged valet, taking grave graceful leave of Deputy Barbaroux.1 She is of stately Norman figure; in her twenty-fifth year; of beautiful still countenance: her name is Charlotte Corday, heretofore styled D’Armans,* while Nobility still was. Barbaroux has given her a Note to Deputy Duperret,—him who once drew his sword in the effervescence. Apparently she will to Paris on some errand? ‘She was a Republican before the Revolution, and never wanted energy.’* A completeness, a decision is in this fair female Figure: ‘by energy she means the spirit that will prompt one to sacrifice himself for his country.’ What if she, this fair young Charlotte, had emerged from her secluded stillness, suddenly like a Star; cruel-lovely, with half-angelic, half-demonic splendour; to gleam for a moment, and in a moment be extinguished: to be held in memory, so bright complete was she, through long centuries!—Quitting Cimmerian Coalitions without, and the dim-simmering Twenty-five millions within, History will look fixedly at this one fair Apparition of a Charlotte Corday; will note whither Charlotte moves, how the little Life burns forth so radiant, then vanishes swallowed of the Night.

With Barbaroux’s Note of Introduction, and slight stock of luggage, we see Charlotte on Tuesday the ninth of July, seated in the Caen Diligence, with a place for Paris. None takes farewell of her, wishes her Good-journey: her Father will find a line left, signifying that she is gone to England, that he must pardon her, and forget her. The drowsy Diligence lumbers along; amid drowsy talk of Politics, and praise of the Mountain; in which she mingles not: all night, all day, and again all night. On Thursday, not long before noon, we are at the bridge of Neuilly; here is Paris with her thousand black domes, the goal and purpose of thy journey! Arrived at the Inn de la Providence in the Rue des Vieux Augustins,* Charlotte demands a room; hastens to bed; sleeps all afternoon and night, till the morrow morning.

On the morrow morning, she delivers her Note to Duperret. It relates to certain Family Papers which are in the Minister of the Interior’s hand; which a Nun at Caen, an old Convent-friend of Charlotte’s, has need of; which Duperret shall assist her in getting: this then was Charlotte’s errand to Paris? She has finished this, in the course of Friday;—yet says nothing of returning. She has seen and silently investigated several things. The Convention, in bodily reality, she has seen; what the Mountain is like. The living physiognomy of Marat she could not see; he is sick at present, and confined to home.

About eight on the Saturday morning, she purchases a large sheath-knife in the Palais-Royal;* then straightway, in the Place des Victoires, takes a hackney-coach: “To the Rue de l’École de Médecine, No. 44.”* It is the residence of the Citoyen Marat!—The Citoyen Marat is ill, and cannot be seen; which seems to disappoint her much. Her business is with Marat, then? Hapless beautiful Charlotte; hapless squalid Marat! From Caen in the utmost West, from Neuchâtel in the utmost East, they two are drawing nigh each other; they two have, very strangely, business together.—Charlotte, returning to her Inn, despatches a short Note to Marat; signifying that she is from Caen, the seat of rebellion; that she desires earnestly to see him, and ‘will put it in his power to do France a great service.’ No answer. Charlotte writes another Note, still more pressing; sets out with it by coach, about seven in the evening, herself. Tired day-labourers have again finished their Week; huge Paris is circling and simmering, manifold, according to its vague wont: this one fair Figure has decision in it; drives straight,—towards a purpose.

It is yellow July evening, we say, the thirteenth of the month; eve of the Bastille day,—when ‘M. Marat,’ four years ago, in the crowd of the Pont Neuf, shrewdly required of that Besenval Hussar-party, which had such friendly dispositions, “to dismount, and give up their arms, then;” and became notable among Patriot men. Four years: what a road he has travelled;—and sits now, about half-past seven of the clock, stewing in slipper-bath; sore afflicted; ill of Revolution Fever,—of what other malady this History had rather not name.* Excessively sick and worn, poor man: with precisely elevenpence-halfpenny of ready money, in paper; with slipper-bath; strong three-footed stool for writing on, the while; and a squalid—Washerwoman, one may call her:* that is his civic establishment in Medical-School Street; thither and not elsewhither has his road led him. Not to the reign of Brotherhood and Perfect Felicity; yet surely on the way towards that?—Hark, a rap again! A musical woman’s-voice, refusing to be rejected: it is the Citoyenne who would do France a service. Marat, recognising from within, cries, Admit her. Charlotte Corday is admitted.

Citoyen Marat, I am from Caen the seat of rebellion, and wished to speak with you.—Be seated, mon enfant. Now what are the Traitors doing at Caen? What Deputies are at Caen?—Charlotte names some Deputies. “Their heads shall fall within a fortnight,” croaks the eager People’s-Friend, clutching his tablets to write: Barbaroux, Pétion, writes he with bare shrunk arm, turning aside in the bath: Pétion, and Louvet, and—Charlotte has drawn her knife from the sheath; plunges it, with one sure stroke, into the writer’s heart. “À moi, chère amie, Help, dear!”* no more could the Death-choked say or shriek. The helpful Washerwoman running in, there is no Friend of the People, or Friend of the Washerwoman, left; but his life with a groan gushes out, indignant, to the shades below.*1

And so Marat People’s-Friend is ended; the lone Stylites has got hurled down suddenly from his Pillar,—whitherward He that made him knows.* Patriot Paris may sound triple and tenfold, in dole and wail; re-echoed by Patriot France; and the Convention, ‘Chabot pale with terror declaring that they are to be all assassinated,’* may decree him Pantheon Honours, Public Funeral, Mirabeau’s dust making way for him;* and Jacobin Societies, in lamentable oratory, summing up his character, parallel him to One, whom they think it honour to call ‘the good Sansculotte,’—whom we name not here;*2 also a Chapel may be made, for the urn that holds his Heart, in the Place du Carrousel;* and new-born children be named Marat; and Lago-di-Como Hawkers bake mountains of stucco into unbeautiful Busts; and David paint his Picture, or Death-Scene; and such other Apotheosis take place as the human genius, in these circumstances, can devise: but Marat returns no more to the light of this Sun.* One sole circumstance we have read with clear sympathy, in the old Moniteur Newspaper: how Marat’s Brother comes from Neuchâtel to ask of the Convention ‘that the deceased Jean-Paul Marat’s musket be given him.’3 For Marat too had a brother, and natural affections; and was wrapt once in swaddling-clothes, and slept safe in a cradle like the rest of us. Ye children of men!*—A sister of his, they say, lives still to this day in Paris.

As for Charlotte Corday her work is accomplished; the recompense of it is near and sure. The chère amie, and neighbours of the house, flying at her, she ‘overturns some movables,’ entrenches herself till the gendarmes arrive; then quietly surrenders; goes quietly to the Abbaye Prison: she alone quiet, all Paris sounding, in wonder, in rage or admiration, round her. Duperret is put in arrest, on account of her; his Papers sealed,—which may lead to consequences. Fauchet, in like manner; though Fauchet had not so much as heard of her. Charlotte, confronted with these two Deputies, praises the grave firmness of Duperret, censures the dejection of Fauchet.

On Wednesday morning, the thronged Palais de Justice and Revolutionary Tribunal can see her face; beautiful and calm: she dates it ‘fourth day of the Preparation of Peace.’ A strange murmur ran through the Hall, at sight of her; you could not say of what character.1 Tinville has his indictments and tape-papers: the cutler of the Palais-Royal will testify that he sold her the sheath-knife; “all these details are needless,” interrupted Charlotte; “it is I that killed Marat.” By whose instigation?—“By no one’s.” What tempted you, then? His crimes. “I killed one man,” added she, raising her voice extremely (extrêmement), as they went on with their questions, “I killed one man to save a hundred thousand; a villain to save innocents; a savage wild-beast to give repose to my country. I was a Republican before the Revolution; I never wanted energy.” There is therefore nothing to be said. The public gazes astonished: the hasty limners sketch her features, Charlotte not disapproving; the men of law proceed with their formalities. The doom is Death as a murderess. To her Advocate she gives thanks; in gentle phrase, in high-flown classical spirit. To the Priest they send her she gives thanks; but needs not any shriving, any ghostly or other aid from him.

On this same evening, therefore, about half-past seven o’clock, from the gate of the Conciergerie, to a City all on tiptoe, the fatal Cart issues: seated on it a fair young creature, sheeted in red smock of Murderess; so beautiful, serene, so full of life; journeying towards death,—alone amid the World. Many take off their hats, saluting reverently; for what heart but must be touched?2 Others growl and howl. Adam Lux, of Mentz, declares that she is greater than Brutus; that it were beautiful to die with her: the head of this young man seems turned. At the Place de la Révolution, the countenance of Charlotte wears the same still smile. The executioners proceed to bind her feet; she resists, thinking it meant as an insult; on a word of explanation, she submits with cheerful apology. As the last act, all being now ready, they take the neckerchief from her neck: a blush of maidenly shame overspreads that fair face and neck; the cheeks were still tinged with it, when the executioner lifted the severed head, to shew it to the people. ‘It is most true,’ says Forster, ‘that he struck the cheek insultingly; for I saw it with my eyes: the Police imprisoned him for it.’1

In this manner have the Beautifullest and the Squalidest come in collision, and extinguished one another. Jean-Paul Marat and Marie-Anne Charlotte Corday both, suddenly, are no more. ‘Day of the Preparation of Peace’? Alas, how were peace possible or preparable, while, for example, the hearts of lovely Maidens, in their convent-stillness, are dreaming not of Love-paradises, and the light of Life;* but of Codrus’-sacrifices, and Death well-earned? That Twenty-five million hearts have got to such temper, this is the Anarchy; the soul of it lies in this: whereof not peace can be the embodyment! The death of Marat, whetting old animosities tenfold, will be worse than any life. O ye hapless Two, mutually extinctive, the Beautiful and the Squalid, sleep ye well,—in the Mother’s bosom that bore you both!

This is the History of Charlotte Corday; most definite, most complete; angelic-demonic: like a Star! Adam Lux goes home, half-delirious; to pour forth his Apotheosis of her, in paper and print; to propose that she have a statue with this inscription, Greater than Brutus.* Friends represent his danger; Lux is reckless; thinks it were beautiful to die with her.*

Chapter II.

In Civil War.

But during these same hours, another guillotine is at work, on another: Charlotte, for the Girondins, dies at Paris today; Chalier, by the Girondins, dies at Lyons tomorrow.

From rumbling of cannon along the streets of that City, it has come to firing of them, to rabid fighting: Nièvre Chol and the Girondins triumph;—behind whom there is, as everywhere, a Royalist Faction waiting to strike in. Trouble enough at Lyons; and the dominant party carrying it with a high hand!* For, indeed, the whole South is astir; incarcerating Jacobins; arming for Girondins: wherefore we have got a ‘Congress of Lyons;’ also a ‘Revolutionary Tribunal of Lyons,’ and Anarchists shall tremble. So Chalier was soon found guilty, of Jacobinism, of murderous Plot, ‘address with drawn dagger on the sixth of February last;’ and, on the morrow, he also travels his final road, along the streets of Lyons, ‘by the side of an ecclesiastic, with whom he seems to speak earnestly,’—the axe now glittering nigh. He could weep, in old years, this man, and ‘fall on his knees on the pavement,’* blessing Heaven at sight of Federation Programs or the like; then he pilgrimed to Paris, to worship Marat and the Mountain: now Marat and he are both gone;—we said he could not end well. Jacobinism groans inwardly, at Lyons; but dare not outwardly. Chalier, when the Tribunal sentenced him, made answer: “My death will cost this City dear.”*

Montélimart Town is not buried under its ruins; yet Marseilles is actually marching, under order of a ‘Lyons Congress;’ is incarcerating Patriots; the very Royalists now shewing face. Against which a General Cartaux fights, though in small force; and with him an Artillery Major, of the name of—Napoleon Buonaparte. This Napoleon, to prove that the Marseillese have no chance ultimately, not only fights but writes; publishes his Supper of Beaucaire, a Dialogue which has become curious.1 Unfortunate Cities, with their actions and their reactions! Violence to be paid with violence in geometrical ratio; Royalism and Anarchism both striking in;—the final net-amount of which geometrical series, what man shall sum?

The Bar of Iron has never yet floated in Marseilles Harbour; but the Body of Rebecqui was found floating, self-drowned there. Hot Rebecqui, seeing how confusion deepened, and Respectability grew poisoned with Royalism, felt that there was no refuge for a Republican but death. Rebecqui disappeared: no one knew whither; till, one morning, they found the empty case or body of him risen to the top, tumbling on the salt waves;2 and perceived that Rebecqui had withdrawn forever.—Toulon likewise is incarcerating Patriots; sending delegates to Congress; intriguing, in case of necessity, with the Royalists and English. Montpellier, Bourdeaux, Nantes: all France, that is not under the swoop of Austria and Cimmeria, seems rushing into madness, and suicidal ruin. The Mountain labours; like a volcano in a burning volcanic Land. Convention Committees, of Surety, of Salvation, are busy night and day:* Convention Commissioners whirl on all highways; bearing olive-branch and sword, or now perhaps sword only. Chaumette and Municipals come daily to the Tuileries demanding a Constitution: it is some weeks now since he resolved, in Townhall, that a Deputation ‘should go every day’ and demand a Constitution, till one were got;3 whereby suicidal France might rally and pacify itself; a thing inexpressibly desirable.

This then is the fruit your Anti-anarchic Girondins have got from that Levying of War in Calvados? This fruit, we may say; and no other whatsoever. For indeed, before either Charlotte’s or Chalier’s head had fallen, the Calvados War itself had, as it were, vanished, dreamlike, in a shriek! With ‘seventy-two Departments’ on our side, one might have hoped better things. But it turns out that Respectabilities, though they will vote, will not fight. Possession always is nine points in Law; but in Lawsuits of this kind, one may say, it is ninety-and-nine points. Men do what they were wont to do; and have immense irresolution and inertia: they obey him who has the symbols that claim obedience. Consider what, in modern society, this one fact means: the Metropolis is with our enemies! Metropolis, Mother-city; rightly so named: all the rest are but as her children, her nurslings. Why, there is not a leathern Diligence, with its post-bags and luggage-boots, that lumbers out from her, but is as a huge life-pulse; she is the heart of all. Cut short that one leathern Diligence, how much is cut short!—General Wimpfen, looking practically into the matter, can see nothing for it but that one should fall back on Royalism; get into communication with Pitt! Dark innuendoes he flings out, to that effect: whereat we Girondins start, horrorstruck. He produces as his Second in command a certain ‘Ci-devant,’ one Comte Puisaye; entirely unknown to Louvet; greatly suspected by him.

Few wars, accordingly, were ever levied of a more insufficient character than this of Calvados. He that is curious in such things may read the details of it in the Memoirs of that same Ci-devant Puisaye, the much-enduring man and Royalist: How our Girondin National forces, marching off with plenty of wind-music, were drawn out about the old Château of Brécourt, in the wood-country near Vernon, to meet the Mountain National forces advancing from Paris. How on the fifteenth afternoon of July, they did meet;—and, as it were, shrieked mutually, and took mutually to flight, without loss. How Puisaye thereafter, for the Mountain Nationals fled first, and we thought ourselves the victors,—was roused from his warm bed in the Castle of Brécourt; and had to gallop without boots; our Nationals, in the night-watches, having fallen unexpectedly into sauve-qui-peut:—and in brief the Calvados War had burnt priming; and the only question now was, Whitherward to vanish, in what hole to hide oneself!1

The National Volunteers rush homewards, faster than they came. The Seventy-two Respectable Departments, says Meillan, ‘all turned round and forsook us, in the space of four-and-twenty hours.’ Unhappy those who, as at Lyons for instance, have gone too far for turning! ‘One morning,’ we find placarded on our Intendance Mansion, the Decree of Convention which casts us Hors la loi, into Outlawry: placarded by our Caen Magistrates;—clear hint that we also are to vanish. Vanish, indeed: but whitherward? Gorsas has friends in Rennes; he will hide there,—unhappily will not lie hid. Guadet, Lanjuinais are on cross roads; making for Bourdeaux. To Bourdeaux! cries the general voice, of Valour alike and of Despair. Some flag of Respectability still floats there, or is thought to float.

Thitherward therefore; each as he can! Eleven of these ill-fated Deputies, among whom we may count as twelfth, Friend Riouffe the Man of Letters, do an original thing: Take the uniform of National Volunteers, and retreat southward with the Breton Battalion, as private soldiers of that corps. These brave Bretons had stood truer by us than any other. Nevertheless, at the end of a day or two, they also do now get dubious, self-divided; we must part from them; and, with some half-dozen as convoy or guide, retreat by ourselves,—a solitary marching detachment, through waste regions of the West.1

Chapter III.

Retreat of the Eleven.

It is one of the notablest Retreats, this of the Eleven, that History presents: The handful of forlorn Legislators retreating there, continually, with shouldered firelock and well-filled cartridge-box, in the yellow autumn; long hundreds of miles between them and Bourdeaux; the country all getting hostile, suspicious of the truth; simmering and buzzing on all sides, more and more. Louvet has preserved the Itinerary of it; a piece worth all the rest he ever wrote.

O virtuous Pétion, with thy early-white head, O brave young Barbaroux, has it come to this? Weary ways, worn shoes, light purse;—encompassed with perils as with a sea! Revolutionary Committees are in every Township; of Jacobin temper; our friends all cowed, our cause the losing one. In the Borough of Moncontour, by ill chance, it is market-day: to the gaping public such transit of a solitary Marching Detachment is suspicious; we have need of energy, of promptitude and luck, to be allowed to march through. Hasten, ye weary pilgrims! The country is getting up; noise of you is bruited day after day, a solitary Twelve retreating in this mysterious manner: with every new day, a wider wave of inquisitive pursuing tumult is stirred up, till the whole West will be in motion. ‘Cussy is tormented with gout, Buzot is too fat for marching.’ Riouffe, blistered, bleeding, marches only on tiptoe; Barbaroux limps with sprained ancle, yet ever cheery, full of hope and valour. Light Louvet glances hare-eyed, not hare-hearted: only virtuous Pétion’s serenity ‘was but once seen ruffled.’1 They lie in straw-lofts, in woody brakes; rudest paillasse on the floor of a secret friend is luxury. They are seized in the dead of night by Jacobin mayors and tap of drum; get off by firm countenance, rattle of muskets, and ready wit.

Of Bourdeaux, through fiery La Vendée and the long geographical spaces that remain, it were madness to think: well, if you can get to Quimper on the sea-coast, and take shipping there. Faster, ever faster! Before the end of the march, so hot has the country grown, it is found advisable to march all night. They do it; under the still night-canopy they plod along;—and yet behold, Rumour has outplodded them. In the paltry Village of Carhaix (be its thatched huts, and bottomless peat-bogs long notable to the Traveller), one is astonished to find light still glimmering: citizens are awake, with rush-lights burning, in that nook of the terrestrial Planet; as we traverse swiftly the one poor street, a voice is heard saying, “There they are, Les voilà qui passent!”2 Swifter, ye doomed lame Twelve: speed ere they can arm; gain the Woods of Quimper before day, and lie squatted there!

The doomed Twelve do it; though with difficulty, with loss of road, with peril and the mistakes of a night. In Quimper are Girondin friends, who perhaps will harbour the homeless, till a Bourdeaux ship weigh. Wayworn, heartworn, in agony of suspense, till Quimper friendship get warning, they lie there, squatted under the thick wet boscage; suspicious of the face of man.* Some pity to the brave; to the unhappy! Unhappiest of all Legislators, O when ye packed your luggage, some score or two-score months ago, and mounted this or the other leathern vehicle, to be Conscript Fathers of a regenerated France, and reap deathless laurels,—did ye think your journey was to lead hither? The Quimper Samaritans find them squatted; lift them up to help and comfort; will hide them in sure places.* Thence let them dissipate gradually; or there they can lie quiet, and write Memoirs, till a Bourdeaux ship sail.

And thus, in Calvados all is dissipated; Romme is out of prison, meditating his Calendar; ringleaders are locked in his room. At Caen the Corday family mourns in silence; Buzot’s House is a heap of dust and demolition; and amid the rubbish sticks a Gallows, with this inscription, Here dwelt the Traitor Buzot who conspired against the Republic.* Buzot and the other vanished Deputies are hors la loi, as we saw; their lives free to take where they can be found. The worse fares it with the poor Arrested visible Deputies at Paris. ‘Arrestment at home’ threatens to become ‘Confinement in the Luxembourg;’ to end: where? For example, what pale-visaged thin man is this, journeying towards Switzerland as a Merchant of Neuchâtel, whom they arrest in the town of Moulins? To Revolutionary Committee he is suspect. To Revolutionary Committee, on probing the matter, he is evidently: Deputy Brissot! Back to thy Arrestment, poor Brissot; or indeed to strait confinement,—whither others are fated to follow. Rabaut has built himself a false-partition, in a friend’s house; lives, in invisible darkness, between two walls. It will end, this same Arrestment business, in Prison, and the Revolutionary Tribunal.

Nor must we forget Duperret, and the seal put on his papers by reason of Charlotte. One Paper is there, fit to breed woe enough: A secret solemn Protest against that suprema dies of the Second of June! This Secret Protest our poor Duperret had drawn up, the same week, in all plainness of speech;* waiting the time for publishing it: to which Secret Protest his signature, and that of other honourable Deputies not a few, stands legibly appended. And now, if the seals were once broken, the Mountain still victorious? Such Protesters, your Merciers, Bailleuls, Seventy-three by the tale, what yet remains of Respectable Girondism in the Convention, may tremble to think!—These are the fruits of levying civil war.

Also we find, that in these last days of July, the famed Siege of Mentz is finished: the Garrison to march out with honours of war; not to serve against the Coalition for a year. Lovers of the Picturesque, and Goethe standing on the Chaussée of Mentz, saw, with due interest, the Procession issuing forth, in all solemnity:

‘Escorted by Prussian horse came first the French Garrison. Nothing could look stranger than this latter: a column of Marseillese, slight, swarthy, party-coloured, in patched clothes, came tripping on;—as if King Edwin had opened the Dwarf Hill, and sent out his nimble Host of Dwarfs. Next followed regular troops; serious, sullen; not as if downcast or ashamed. But the remarkablest appearance, which struck every one, was that of the Chasers (Chasseurs) coming out mounted: they had advanced quite silent to where we stood, when their Band struck up the Marseillaise. This revolutionary Te-Deum has in itself something mournful and bodeful, however briskly played; but at present they gave it in altogether slow time, proportionate to the creeping step they rode at. It was piercing and fearful, and a most serious-looking thing, as these cavaliers, long, lean men, of a certain age, with mien suitable to the music, came pacing on: singly you might have likened them to Don Quixote; in mass, they were highly dignified.

‘But now a single troop became notable: that of the Commissioners or Représentans. Merlin of Thionville, in hussar uniform, distinguishing himself by wild beard and look, had another person in similar costume on his left; the crowd shouted out, with rage, at sight of this latter, the name of a Jacobin Townsman and Clubbist; and shook itself to seize him. Merlin drew bridle; referred to his dignity as French Representative, to the vengeance that should follow any injury done; he would advise every one to compose himself, for this was not the last time they would see him here.’1 Thus rode Merlin; threatening in defeat. But what now shall stem that tide of Prussians setting in through the opened North-East? Lucky, if fortified Lines of Weissembourg, and impassabilities of Vosges Mountains, confine it to French Alsace, keep it from submerging the very heart of the country!

Furthermore, precisely in the same days, Valenciennes Siege is finished, in the North-West:—fallen, under the red hail of York! Condé fell some fortnight since. Cimmerian Coalition presses on. What seems very notable too, on all these captured French Towns there flies not the Royalist fleur-de-lys, in the name of a new Louis the Pretender; but the Austrian flag flies; as if Austria meant to keep them for herself! Perhaps General Custine, still in Paris, can give some explanation of the fall of these strong-places?* Mother Society, from tribune and gallery, growls loud that he ought to do it;—remarks, however, in a splenetic manner that ‘the Monsieurs of the Palais-Royal’ are calling Long-life to this General.

The Mother Society, purged now, by successive ‘scrutinies or épurations,’ from all taint of Girondism, has become a great Authority: what we can call shield-bearer, or bottle-holder, nay call it fugleman, to the purged National Convention itself. The Jacobins Debates are reported in the Moniteur, like Parliamentary ones.

Chapter IV.

O Nature.*

But looking more specially into Paris City, what is this that History, on the 10th of August, Year One of Liberty, ‘by old-style, year 1793,’ discerns there? Praised be the Heavens, a new Feast of Pikes!

For Chaumette’s ‘Deputation every day’ has worked out its result: a Constitution. It was one of the rapidest Constitutions ever put together; made, some say in eight days, by Hérault Séchelles and others: probably a workmanlike, roadworthy Constitution enough;—on which point, however, we are, for some reasons, little called to form a judgment. Workmanlike or not, the Forty-four Thousand Communes of France, by overwhelming majorities, did hasten to accept it; glad of any Constitution whatsoever. Nay Departmental Deputies have come, the venerablest Republicans of each Department, with solemn message of Acceptance; and now what remains but that our new Final Constitution be proclaimed, and sworn to, in Feast of Pikes? The Departmental Deputies, we say, are come some time ago; Chaumette very anxious about them, lest Girondin Monsieurs, Agio-jobbers, or were it even Filles de joie of a Girondin temper, corrupt their morals.1 Tenth of August, immortal Anniversary, greater almost than Bastille July, is the Day.

Painter David has not been idle. Thanks to David and the French genius, there steps forth into the sunlight, this day, a Scenic Phantasmagory unexampled:—whereof History, so occupied with Real Phantasmagories, will say but little.

For one thing, History can notice with satisfaction, on the ruins of the Bastille, a Statue of Nature; gigantic, spouting water from her two mammelles. Not a Dream this; but a Fact, palpable visible. There she spouts, great Nature; dim, before daybreak. But as the coming Sun ruddies the East, come countless Multitudes, regulated and unregulated; come Departmental Deputies, come Mother Society and Daughters; comes National Convention, led on by handsome Hérault; soft wind-music breathing note of expectation. Lo, as great Sol scatters his first fire-handful, tipping the hills and chimney-heads with gold, Hérault is at great Nature’s feet (she is Plaster of Paris merely); Hérault lifts, in an iron saucer, water spouted from the sacred breasts; drinks of it, with an eloquent Pagan Prayer, beginning, “O Nature!” and all the Departmental Deputies drink, each with what best suitable ejaculation or prophetic-utterance is in him;—amid breathings, which become blasts, of wind-music; and the roar of artillery and human throats: finishing well the first act of this solemnity.

Next are processionings along the Boulevards: Deputies or Officials bound together by long indivisible tricolor riband; general ‘members of the Sovereign’ walking pellmell, with pikes, with hammers, with the tools and emblems of their crafts; among which we notice a Plough, and ancient Baucis and Philemon seated on it, drawn by their children. Many-voiced harmony and dissonance filling the air. Through Triumphal Arches enough: at the basis of the first of which, we descry—whom thinkest thou?—the Heroines of the Insurrection of Women. Strong Dames of the Market, they sit there (Théroigne too ill to attend, one fears), with oak-branches, tricolor bedizenment; firm-seated on their Cannons. To whom handsome Hérault, making pause of admiration, addresses soothing eloquence; whereupon they rise and fall into the march.

And now mark, in the Place de la Révolution, what other August Statue may this be; veiled in canvas,—which swiftly we shear off by pulley and cord? The Statue of Liberty! She too is of plaster, hoping to become of metal; stands where a Tyrant Louis Quinze once stood. ‘Three thousand birds’ are let loose, into the whole world, with labels round their neck, We are free; imitate us. Holocaust of Royalist and ci-devant trumpery, such as one could still gather, is burnt; pontifical eloquence must be uttered, by handsome Hérault, and Pagan orisons offered up.

And then forward across the River; where is new enormous Statuary; enormous plaster Mountain; Hercules-Peuple, with uplifted all-conquering club; ‘many-headed Dragon of Girondin Federalism rising from fetid marsh;’—needing new eloquence from Hérault. To say nothing of Champ-de-Mars, and Fatherland’s Altar there; with urn of slain Defenders, Carpenter’s-level of the Law; and such exploding, gesticulating and perorating, that Hérault’s lips must be growing white, and his tongue cleaving to the roof of his mouth.1*

Towards six o’clock let the wearied President, let Paris Patriotism generally sit down to what repast, and social repasts, can be had; and with flowing tankard or light-mantling glass, usher in this New and Newest Era. In fact, is not Romme’s New Calendar getting ready? On all housetops flicker little tricolor Flags, their flagstaff a Pike and Liberty-Cap. On all house-walls, for no Patriot, not suspect, will be behind another, there stand printed these words: Republic one and indivisible, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, or Death.*

As to the New Calendar, we may say here rather than elsewhere that speculative men have long been struck with the inequalities and incongruities of the Old Calendar; that a New one has long been as good as determined on. Maréchal the Atheist, almost ten years ago, proposed a New Calendar, free at least from superstition: this the Paris Municipality would now adopt, in defect of a better; at all events, let us have either this of Maréchal’s or a better,—the New Era being come. Petitions, more than once, have been sent to that effect; and indeed, for a year past, all Public Bodies, Journalists, and Patriots in general, have dated First Year of the Republic. It is a subject not without difficulties. But the Convention has taken it up; and Romme, as we say, has been meditating it; not Maréchal’s New Calendar, but a better New one of Romme’s and our own. Romme, aided by a Monge, a Lagrange and others, furnishes mathematics; Fabre d’Eglantine furnishes poetic nomenclature: and so, on the 5th of October 1793, after trouble enough, they bring forth this New Republican Calendar of theirs, in a complete state; and by Law, get it put in action.

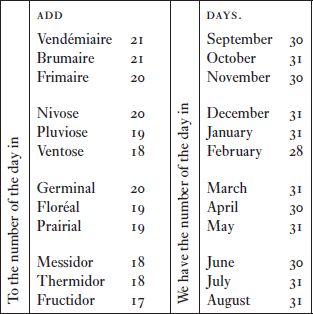

Four equal Seasons, Twelve equal Months of Thirty days each: this makes three hundred and sixty days; and five odd days remain to be disposed of. The five odd days we will make Festivals, and name the five Sansculottides, or Days without Breeches. Festival of Genius; Festival of Labour; of Actions; of Rewards; of Opinion: these are the five Sansculottides. Whereby the great Circle, or Year, is made complete: solely every fourth year, whilom called Leap-year, we introduce a sixth Sansculottide; and name it Festival of the Revolution. Now as to the day of commencement, which offers difficulties, is it not one of the luckiest coincidences that the Republic herself commenced on the 21st of September; close on the Autumnal Equinox? Autumnal Equinox, at midnight for the meridian of Paris, in the year whilom Christian 1792, from that moment shall the New Era reckon itself to begin. Vendémiaire, Brumaire, Frimaire; or as one might say, in mixed English, Vintagearious, Fogarious, Frostarious: these are our three Autumn months. Nivose, Pluviose, Ventose, or say, Snowous, Rainous, Windous, make our Winter season. Germinal, Floréal, Prairial, or Buddal, Floweral, Meadowal, are our Spring season. Messidor, Thermidor, Fructidor, that is to say (dor being Greek for gift), Reapidor, Heatidor, Fruitidor, are Republican Summer. These Twelve, in a singular manner, divide the Republican Year. Then as to minuter subdivisions, let us venture at once on a bold stroke: adopt your decimal subdivision; and instead of the world-old Week, or Se’ennight, make it a Tennight, or Décade;—not without results. There are three Decades, then, in each of the months; which is very regular; and the Décadi, or Tenth-day, shall always be the ‘Day of Rest.’ And the Christian Sabbath, in that case? Shall shift for itself!

This, in brief, is the New Calendar of Romme and the Convention; calculated for the meridian of Paris, and Gospel of Jean Jacques: not one of the least afflicting occurrences for the actual British reader of French History;—confusing the soul with Messidors, Meadowals; till at last, in self-defence, one is forced to construct some ground-scheme, or rule of Commutation from New-style to Old-style, and have it lying by him. Such ground-scheme, almost worn out in our service, but still legible and printable, we shall now, in a Note, present to the reader. For the Romme Calendar, in so many Newspapers, Memoirs, Public Acts, has stamped itself deep into that section of Time: a New Era that lasts some Twelve years and odd is not to be despised.1 Let the reader, therefore, with such ground-scheme, help himself, where needful, out of New-style into Old-style, called also ‘slave-style, stile-esclave;’—whereof we, in these pages, shall as much as possible use the latter only.

Thus with new Feast of Pikes, and New Era or New Calendar, did France accept her New Constitution: the most Democratic Constitution ever committed to paper. How it will work in practice? Patriot Deputations, from time to time, solicit fruition of it; that it be set a-going. Always, however, this seems questionable; for the moment, unsuitable. Till, in some weeks, Salut Public, through the organ of Saint-Just, makes report, that, in the present alarming circumstances, the state of France is Revolutionary; that her ‘Government must be Revolutionary till the Peace.’ Solely as Paper, then, and as a Hope, must this poor New Constitution exist;—in which shape we may conceive it lying, even now, with an infinity of other things, in that Limbo near the Moon. Further than paper it never got, nor ever will get.

Chapter V.

Sword of Sharpness.

In fact it is something quite other than paper theorems, it is iron and audacity that France now needs.

Is not La Vendée still blazing;—alas too literally; rogue Rossignol burning the very corn-mills? General Santerre could do nothing there; General Rossignol, in blind fury, often in liquor, can do less than nothing. Rebellion spreads, grows ever madder. Happily those lean Quixote-figures, whom we saw retreating out of Mentz, ‘bound not to serve against the Coalition for a year,’ have got to Paris. National Convention packs them into post-vehicles and conveyances; sends them swiftly, by post, into La Vendée. There valiantly struggling, in obscure battle and skirmish, under rogue Rossignol, let them, unlaurelled, save the Republic, and ‘be cut down gradually to the last man.’1

Does not the Coalition, like a fire-tide, pour in; Prussia through the opened North-East; Austria, England through the North-West? General Houchard prospers no better there than General Custine did: let him look to it! Through the Eastern and the Western Pyrenees Spain has deployed itself; spreads, rustling with Bourbon banners, over the face of the South. Ashes and embers of confused Girondin civil war covered that region already. Marseilles is damped down, not quenched; to be quenched in blood. Toulon, terrorstruck, too far gone for turning, has flung itself, ye righteous Powers,—into the hands of the English! On Toulon Arsenal there flies a Flag,—nay not even the Fleur-de-lys of a Louis Pretender; there flies that accursed St. George’s Cross of the English and Admiral Hood! What remnant of sea-craft, arsenals, roperies, war-navy France had, has given itself to these enemies of human nature, ‘ennemis du genre humain.’ Beleaguer it, bombard it, ye Commissioners Barras, Fréron, Robespierre Junior; thou General Cartaux, General Dugommier; above all, thou remarkable Artillery-Major, Napoleon Buonaparte! Hood is fortifying himself, victualling himself; means, apparently, to make a new Gibraltar of it.

But lo, in the Autumn night, late night, among the last of August, what sudden red sunblaze is this that has risen over Lyons City; with a noise to deafen the world? It is the Powder-tower of Lyons, nay the Arsenal with four Powder-towers, which has caught fire in the Bombardment; and sprung into the air, carrying ‘a hundred and seventeen houses’* after it. With a light, one fancies, as of the noon sun; with a roar second only to the Last Trumpet!* All living sleepers far and wide it has awakened. What a sight was that, which the eye of History saw, in the sudden nocturnal sunblaze! The roofs of hapless Lyons, and all its domes and steeples made momentarily clear; Rhone and Soane streams flashing suddenly visible; and height and hollow, hamlet and smooth stubblefield, and all the region round;—heights, alas, all scarped and counterscarped, into trenches, curtains, redouts; blue Artillery-men, little Powder-devilkins, plying their hell-trade there, through the not ambrosial night!* Let the darkness cover it again; for it pains the eye. Of a truth, Chalier’s death is costing this City dear. Convention Commissioners, Lyons Congresses have come and gone; and action there was and reaction; bad ever growing worse; till it has come to this: Commissioner Dubois-Crancé, ‘with seventy thousand men, and all the Artillery of several Provinces,’* bombarding Lyons day and night.

Worse things still are in store. Famine is in Lyons, and ruin, and fire. Desperate are the sallies of the besieged; brave Précy, their National Colonel and Commandant, doing what is in man: desperate but ineffectual. Provisions cut off; nothing entering our city but shot and shells! The Arsenal has roared aloft; the very Hospital will be battered down, and the sick buried alive. A black Flag hung on this latter noble Edifice, appealing to the pity of the besiegers; for though maddened, were they not still our brethren? In their blind wrath, they took it for a flag of defiance, and aimed thitherward the more. Bad is growing ever worse here: and how will the worse stop, till it have grown worst of all? Commissioner Dubois will listen to no pleading, to no speech, save this only, We surrender at discretion. Lyons contains in it subdued Jacobins; dominant Girondins; secret Royalists. And now, mere deaf madness and cannon-shot enveloping them, will not the desperate Municipality fly, at last, into the arms of Royalism itself? Majesty of Sardinia was to bring help, but it failed. Emigrant d’Autichamp, in name of the Two Pretender Royal Highnesses, is coming through Switzerland with help; coming, not yet come: Précy hoists the Fleur-de-lys!

At sight of which, all true Girondins sorrowfully fling down their arms:—Let our Tricolor brethren storm us, then, and slay us in their wrath; with you we conquer not. The famishing women and children are sent forth: deaf Dubois sends them back;—rains in mere fire and madness. Our ‘redouts of cotton-bags’ are taken, retaken; Précy under his Fleur-de-lys is valiant as Despair. What will become of Lyons? It is a siege of seventy days.1

Or see, in these same weeks, far in the Western waters: breasting through the Bay of Biscay, a greasy dingy little Merchant-ship, with Scotch skipper; under hatches whereof sit, disconsolate,—the last forlorn nucleus of Girondism, the Deputies from Quimper! Several have dissipated themselves, whithersoever they could. Poor Riouffe fell into the talons of Revolutionary Committee, and Paris Prison. The rest sit here under hatches; reverend Pétion with his grey hair, angry Buzot, suspicious Louvet, brave young Barbaroux, and others. They have escaped from Quimper, in this sad craft; are now tacking and struggling; in danger from the waves, in danger from the English, in still worse danger from the French;—banished by Heaven and Earth to the greasy belly of this Scotch skipper’s Merchant-vessel, unfruitful Atlantic* raving round. They are for Bourdeaux, if peradventure hope yet linger there. Enter not Bourdeaux, O Friends! Bloody Convention Representatives, Tallien and such like, with their Edicts, with their Guillotine, have arrived there; Respectability is driven under ground; Jacobinism lords it on high. From that Réole landingplace, or Beak of Ambès, as it were, Pale Death, waving his Revolutionary Sword of Sharpness, waves you elsewhither!

On one side or the other of that Bec d’Ambès, the Scotch Skipper with difficulty moors, a dexterous greasy man; with difficulty lands his Girondins;—who, after reconnoitring, must rapidly burrow in the Earth; and so, in subterranean ways, in friends’ back-closets, in cellars, barn-lofts, in caves of Saint-Emilion and Libourne, stave off cruel Death.1 Unhappiest of all Senators!

Chapter VI.

Risen against Tyrants.

Against all which incalculable impediments, horrors and disasters, what can a Jacobin Convention oppose? The uncalculating Spirit of Jacobinism, and Sansculottic sans-formulistic Frenzy! Our Enemies press in on us, says Danton, but they shall not conquer us, “we will burn France to ashes rather,* nous brûlerons la France.”

Committees, of Sureté, of Salut, have raised themselves ‘à la hauteur, to the height of circumstances.’* Let all mortals raise themselves à la hauteur. Let the Forty-four thousand Sections and their Revolutionary Committees stir every fibre of the Republic; and every Frenchman feel that he is to do or die. They are the life-circulation of Jacobinism, these Sections and Committees: Danton, through the organ of Barrère and Salut Public, gets decreed, That there be in Paris, by law, two meetings of Section weekly; also, that the Poorer Citizen be paid for attending, and have his day’s-wages of Forty Sous.2 This is the celebrated ‘Law of the Forty Sous;’ fiercely stimulant to Sansculottism, to the life-circulation of Jacobinism.

On the twenty-third of August, Committee of Public Salvation, as usual through Barrère, had promulgated, in words not unworthy of remembering, their Report, which is soon made into a Law, of Levy in Mass. ‘All France, and whatsoever it contains of men or resources, is put under requisition,’ says Barrère; really in Tyrtæan words, the best we know of his. ‘The Republic is one vast besieged city.’* Two hundred and fifty Forges shall, in these days, be set up in the Luxembourg Garden, and round the outer wall of the Tuileries; to make gun-barrels; in sight of Earth and Heaven! From all hamlets, towards their Departmental Town; from all Departmental Towns, towards the appointed Camp and seat of war, the Sons of Freedom shall march; their banner is to bear: ‘Le Peuple Français debout contre les Tyrans, The French People risen against Tyrants.’ ‘The young men shall go to the battle; it is their task to conquer: the married men shall forge arms, transport baggage and artillery; provide subsistence: the women shall work at soldiers’ clothes, make tents; serve in the hospitals: the children shall scrape old-linen into surgeon’s-lint: the aged men shall have themselves carried into public places; and there, by their words, excite the courage of the young; preach hatred to Kings and unity to the Republic.’1 Tyrtæan words; which tingle through all French hearts.

In this humour, then, since no other serves, will France rush against its enemies. Headlong, reckoning no cost or consequence; heeding no law or rule but that supreme law, Salvation of the People! The weapons are, all the iron that is in France; the strength is, that of all the men, women and children that are in France. There, in their two hundred and fifty shed-smithies, in Garden of Luxembourg or Tuileries, let them forge gun-barrels, in sight of Heaven and Earth.

Nor with heroic daring against the Foreign foe, can black vengeance against the Domestic be wanting. Life-circulation of the Revolutionary Committees being quickened by that Law of the Forty Sous, Deputy Merlin, not the Thion-viller, whom we saw ride out of Mentz, but Merlin of Douai, named subsequently Merlin Suspect,—comes, about a week after, with his world-famous Law of the Suspect: ordering all Sections, by their Committees, instantly to arrest all Persons Suspect; and explaining withal who the Arrestable and Suspect specially are. ‘Are Suspect,’ says he, ‘all who by their actions, by their connexions, speakings, writings have’—in short become Suspect.2 Nay Chaumette, illuminating the matter still further, in his Municipal Placards and Proclamations, will bring it about that you may almost recognise a Suspect on the streets, and clutch him there,—off to Committee, and Prison. Watch well your words, watch well your looks: if Suspect of nothing else, you may grow, as came to be a saying, ‘Suspect of being Suspect’!* For are we not in a State of Revolution?

No frightfuller Law ever ruled in a Nation of men. All Prisons and Houses of Arrest in French land are getting crowded to the ridge-tile: Forty-four thousand Committees, like as many companies of reapers or gleaners, gleaning France, are gathering their harvest, and storing it in these Houses. Harvest of Aristocrat tares! Nay lest the Forty-four thousand, each on its own harvest-field, prove insufficient, we are to have an ambulant ‘Revolutionary Army:’* six thousand strong, under right captains, this shall perambulate the country at large, and strike in wherever it finds such harvest-work slack. So have Municipality and Mother Society petitioned; so has Convention decreed.1 Let Aristocrats, Federalists, Monsieurs vanish, and all men tremble:* ‘the Soil of Liberty shall be purged,’—with a vengeance!

Neither hitherto has the Revolutionary Tribunal been keeping holyday. Blanchelande, for losing Saint-Domingo; ‘Conspirators of Orléans,’ for ‘assassinating,’ for assaulting the sacred Deputy Léonard-Bourdon: these with many Nameless, to whom life was sweet, have died. Daily the great Guillotine has its due. Like a black Spectre, daily at eventide, glides the Death-tumbril through the variegated throng of things. The variegated street shudders at it, for the moment; next moment forgets it: The Aristocrats! They were guilty against the Republic; their death, were it only that their goods are confiscated, will be useful to the Republic; Vive la République!

In the last days of August, fell a notabler head: General Custine’s. Custine was accused of harshness, of unskilfulness, perfidiousness; accused of many things: found guilty, we may say, of one thing, unsuccessfulness. Hearing his unexpected Sentence, ‘Custine fell down before the Crucifix,’ silent for the space of two hours: he fared, with moist eyes and a look of prayer, towards the Place de la Révolution; glanced upwards at the clear suspended axe; then mounted swiftly aloft,2 swiftly was struck away from the lists of the Living. He had fought in America; he was a proud, brave man; and his fortune led him hither.

On the 2d of this same month, at three in the morning, a vehicle rolled off, with closed blinds, from the Temple to the Conciergerie. Within it were two Municipals; and Marie-Antoinette, once Queen of France! There in that Conciergerie, in ignominious dreary cell, she, secluded from children, kindred, friend and hope, sits long weeks; expecting when the end will be.3

The Guillotine, we find, gets always a quicker motion, as other things are quickening. The Guillotine, by its speed of going, will give index of the general velocity of the Republic. The clanking of its huge axe, rising and falling there, in horrid systole-diastole, is portion of the whole enormous Life-movement and pulsation of the Sansculottic System!—‘Orléans Conspirators’ and Assaulters had to die, in spite of much weeping and entreating; so sacred is the person of a Deputy. Yet the sacred can become desecrated: your very Deputy is not greater than the Guillotine. Poor Deputy Journalist Gorsas: we saw him hide at Rennes, when the Calvados War burnt priming. He stole afterwards, in August, to Paris; lurked several weeks about the Palais ci-devant Royal; was seen there, one day; was clutched, identified, and without ceremony, being already ‘out of the Law,’ was sent to the Place de la Révolution. He died, recommending his wife and children to the pity of the Republic. It is the ninth day of October 1793. Gorsas is the first Deputy that dies on the scaffold; he will not be the last.

Ex-Mayor Bailly is in Prison; Ex-Procureur Manuel. Brissot and our poor Arrested Girondins have become Incarcerated Indicted Girondins; universal Jacobinism clamouring for their punishment. Duperret’s Seals are broken! Those Seventy-three Secret Protesters, suddenly one day, are reported upon, are decreed accused; the Convention-doors being ‘previously shut,’ that none implicated might escape. They were marched, in a very rough manner, to Prison that evening. Happy those of them who chanced to be absent! Condorcet has vanished into darkness; perhaps, like Rabaut, sits between two walls, in the house of a friend.

Chapter VII.

Marie-Antoinette.

On Monday the Fourteenth of October, 1793, a Cause is pending in the Palais de Justice, in the new Revolutionary Court, such as these old stone-walls never witnessed: the Trial of Marie-Antoinette. The once brightest of Queens, now tarnished, defaced, forsaken, stands here at Fouquier-Tinville’s Judgment-bar; answering for her life. The Indictment was delivered her last night.1 To such changes of human fortune what words are adequate? Silence alone is adequate.

There are few Printed things one meets with, of such tragic, almost ghastly, significance as those bald Pages of the Bulletin du Tribunal Révolutionnaire, which bear title, Trial of the Widow Capet. Dim, dim, as if in disastrous eclipse; like the pale kingdoms of Dis! Plutonic Judges, Plutonic Tinville; encircled, nine times, with Styx and Lethe, with Fire-Phlegethon and Cocytus named of Lamentation! The very witnesses summoned are like Ghosts: exculpatory, inculpatory, they themselves are all hovering over death and doom; they are known, in our imagination, as the prey of the Guillotine. Tall ci-devant Count d’Estaing, anxious to shew himself Patriot, cannot escape; nor Bailly, who, when asked If he knows the Accused, answers with a reverent inclination towards her, “Ah, yes, I know Madame.”* Ex-Patriots are here, sharply dealt with, as Procureur Manuel; Ex-Ministers, shorn of their splendour. We have cold Aristocratic impassivity, faithful to itself even in Tartarus; rabid stupidity, of Patriot Corporals, Patriot Washerwomen, who have much to say of Plots, Treasons, August Tenth, old Insurrection of Women. For all now has become a crime, in her who has lost.

Marie-Antoinette, in this her utter abandonment, and hour of extreme need, is not wanting to herself, the imperial woman. Her look, they say, as that hideous Indictment was reading, continued calm; ‘she was sometimes observed moving her fingers, as when one plays on the piano.’* You discern, not without interest, across that dim Revolutionary Bulletin itself, how she bears herself queenlike. Her answers are prompt, clear, often of Laconic brevity; resolution, which has grown contemptuous without ceasing to be dignified, veils itself in calm words. “You persist then in denial?”—“My plan is not denial: it is the truth I have said, and I persist in that.” Scandalous Hébert has borne his testimony as to many things: as to one thing, concerning Marie-Antoinette and her little Son,—wherewith Human Speech had better not further be soiled.* She has answered Hébert; a Juryman begs to observe that she has not answered as to this. “I have not answered,” she exclaims with noble emotion, “because Nature refuses to answer such a charge brought against a Mother. I appeal to all the Mothers that are here.”* Robespierre, when he heard of it, broke out into something almost like swearing at the brutish blockheadism of this Hébert;1 on whose foul head* his foul lie has recoiled. At four o’clock on Wednesday morning, after two days and two nights of interrogating, jury-charging, and other darkening of counsel,* the result comes out: sentence of Death. “Have you anything to say?” The Accused shook her head, without speech. Night’s candles are burning out;* and with her too Time is finishing, and it will be Eternity and Day. This Hall of Tinville’s is dark, ill-lighted except where she stands. Silently she withdraws from it, to die.

Two Processions,* or Royal Progresses, three-and-twenty years apart, have often struck us with a strange feeling of contrast. The first is of a beautiful Archduchess and Dauphiness, quitting her Mother’s City, at the age of Fifteen; towards hopes such as no other Daughter of Eve then had: ‘On the morrow,’ says Weber an eye-witness, ‘the Dauphiness left Vienna. The whole City crowded out; at first with a sorrow which was silent. She appeared: you saw her sunk back into her carriage; her face bathed in tears; hiding her eyes now with her handkerchief, now with her hands; several times putting out her head to see yet again this Palace of her Fathers, whither she was to return no more. She motioned her regret, her gratitude to the good Nation, which was crowding here to bid her farewell. Then arose not only tears; but piercing cries, on all sides. Men and women alike abandoned themselves to such expression of their sorrow. It was an audible sound of wail, in the streets and avenues of Vienna. The last Courier that followed her disappeared, and the crowd melted away.’1

The young imperial Maiden of Fifteen has now become a worn discrowned Widow of Thirty-eight; grey before her time: this is the last Procession: ‘Few minutes after the Trial ended, the drums were beating to arms in all Sections; at sunrise the armed force was on foot, cannons getting placed at the extremities of the Bridges, in the Squares, Crossways, all along from the Palais de Justice to the Place de la Révolution. By ten o’clock, numerous patrols were circulating in the Streets; thirty thousand foot and horse drawn up under arms. At eleven, Marie-Antoinette was brought out. She had on an undress of piqué blanc: she was led to the place of execution, in the same manner as an ordinary criminal; bound, on a Cart; accompanied by a Constitutional Priest in Lay dress; escorted by numerous detachments of infantry and cavalry. These, and the double row of troops all along her road, she appeared to regard with indifference. On her countenance there was visible neither abashment nor pride. To the cries of Vive la République and Down with Tyranny, which attended her all the way, she seemed to pay no heed. She spoke little to her Confessor. The tricolor Streamers on the housetops occupied her attention, in the Streets du Roule and Saint-Honoré; she also noticed the Inscriptions on the house-fronts. On reaching the Place de la Révolution, her looks turned towards the Jardin National, whilom Tuileries; her face at that moment gave signs of lively emotion. She mounted the Scaffold with courage enough;* at a quarter past Twelve, her head fell; the Executioner shewed it to the people, amid universal long-continued cries of Vive la République.’*2

Chapter VIII.

The Twenty-Two.

Whom next, O Tinville? The next are of a different colour: our poor Arrested Girondin Deputies. What of them could still be laid hold of; our Vergniaud, Brissot, Fauchet, Valazé, Gensonné; the once flower of French Patriotism, Twenty-two by the tale: hither, at Tinville’s Bar, onward from ‘safeguard of the French People,’ from confinement in the Luxembourg, imprisonment in the Conciergerie, have they now, by the course of things, arrived. Fouquier-Tinville must give what account of them he can.

Undoubtedly this Trial of the Girondins is the greatest that Fouquier has yet had to do. Twenty-two, all chief Republicans, ranged in a line there; the most eloquent in France; Lawyers too; not without friends in the auditory. How will Tinville prove these men guilty of Royalism, Federalism, Conspiracy against the Republic? Vergniaud’s eloquence awakes once more; ‘draws tears,’ they say. And Journalists report, and the Trial lengthens itself out day after day; ‘threatens to become eternal,’* murmur many. Jacobinism and Municipality rise to the aid of Fouquier. On the 28th of the month, Hébert and others come in deputation to inform a Patriot Convention that the Revolutionary Tribunal is quite ‘shackled by Forms of Law;’ that a Patriot Jury ought to have ‘the power of cutting short, of terminer les débats, when they feel themselves convinced.’ Which pregnant suggestion, of cutting short, passes itself, with all despatch, into a Decree.

Accordingly, at ten o’clock on the night of the 30th of October, the Twenty-two, summoned back once more, receive this information, That the Jury feeling themselves convinced have cut short, have brought in their verdict; that the Accused are found guilty, and the Sentence on one and all of them is, Death with confiscation of goods.

Loud natural clamour rises among the poor Girondins; tumult; which can only be repressed by the gendarmes. Valazé stabs himself; falls down dead on the spot. The rest, amid loud clamour and confusion, are driven back to their Conciergerie; Lasource exclaiming, “I die on the day when the People have lost their reason; ye will die when they recover it.”1 No help! Yielding to violence, the Doomed uplift the Hymn of the Marseillese; return singing to their dungeon.

Riouffe, who was their Prison-mate in these last days, has lovingly recorded what death they made. To our notions, it is not an edifying death. Gay satirical Pot-pourri by Ducos; rhymed Scenes of Tragedy, wherein Barrère and Robespierre discourse with Satan; death’s eve spent in ‘singing’ and ‘sallies of gaiety,’ with ‘discourses on the happiness of peoples:’ these things, and the like of these, we have to accept for what they are worth. It is the manner in which the Girondins make their Last Supper.* Valazé, with bloody breast, sleeps cold in death; hears not the singing. Vergniaud has his dose of poison; but it is not enough for his friends, it is enough only for himself; wherefore he flings it from him; presides at this Last Supper of the Girondins, with wild coruscations of eloquence, with song and mirth. Poor human Will struggles to assert itself; if not in this way, then in that.1

But on the morrow morning all Paris is out; such a crowd as no man had seen. The Death-carts, Valazé’s cold corpse stretched among the yet living Twenty-one, roll along. Bareheaded, hands bound; in their shirt-sleeves, coat flung loosely round the neck: so fare the eloquent of France; bemurmured, beshouted. To the shouts of Vive la République, some of them keep answering with counter-shouts of Vive la République. Others, as Brissot, sit sunk in silence. At the foot of the scaffold they again strike up, with appropriate variations, the Hymn of the Marseillese. Such an act of music; conceive it well! The yet Living chant there; the chorus so rapidly wearing weak! Samson’s axe is rapid; one head per minute, or little less. The chorus is wearing weak; the chorus is worn out;—farewell forevermore, ye Girondins. Te-Deum Fauchet has become silent; Valazé’s dead head is lopped: the sickle of the Guillotine has reaped the Girondins all away. ‘The eloquent, the young, the beautiful and brave!’ exclaims Riouffe.* O Death, what feast is toward in thy ghastly Halls?*

Nor alas, in the far Bourdeaux region, will Girondism fare better. In caves of Saint-Emilion, in loft and cellar, the weariest months roll on; apparel worn, purse empty; wintry November come; under Tallien and his Guillotine, all hope now gone. Danger drawing ever nigher, difficulty pressing ever straiter, they determine to separate. Not unpathetic the farewell; tall Barbaroux, cheeriest of brave men, stoops to clasp his Louvet: “In what place soever thou findest my Mother,” cries he, “try to be instead of a son to her: no resource of mine but I will share with thy Wife, should chance ever lead me where she is.”2

Louvet went with Guadet, with Salles and Valadi; Barbaroux with Buzot and Pétion. Valadi soon went southward, on a way of his own. The two friends and Louvet had a miserable day and night; the 14th of the November month, 1793. Sunk in wet, weariness and hunger, they knock, on the morrow, for help, at a friend’s country-house; the fainthearted friend refuses to admit them. They stood therefore under trees, in the pouring rain. Flying desperate, Louvet thereupon will to Paris. He sets forth, there and then, splashing the mud on each side of him, with a fresh strength gathered from fury or frenzy. He passes villages, finding ‘the sentry asleep in his box in the thick rain;’ he is gone, before the man can call after him. He bilks Revolutionary Committees; rides in carriers’ carts, covered carts and open; lies hidden in one, under knapsacks and cloaks of soldiers’ wives on the Street of Orléans, while men search for him; has hairbreadth escapes that would fill three romances: finally he gets to Paris to his fair Helpmate; gets to Switzerland, and waits better days.

Poor Guadet and Salles were both taken, ere long; they died by the Guillotine in Bourdeaux; drums beating to drown their voice. Valadi also is caught, and guillotined. Barbaroux and his two comrades weathered it longer, into the summer of 1794; but not long enough. One July morning, changing their hiding place, as they have often to do, ‘about a league from Saint-Emilion, they observe a great crowd of country-people:’ doubtless Jacobins come to take them? Barbaroux draws a pistol, shoots himself dead. Alas, and it was not Jacobins; it was harmless villagers going to a village wake. Two days afterwards, Buzot and Pétion were found in a Corn-field, their bodies half-eaten by dogs.1

Such was the end of Girondism. They arose to regenerate France, these men; and have accomplished this. Alas, whatever quarrel we had with them, has not their cruel fate abolished it? Pity only survives. So many excellent souls of heroes sent down to Hades; they themselves given as a prey of dogs and all manner of birds!* But, here too, the will of the Supreme Power was accomplished. As Vergniaud said: ‘the Revolution, like Saturn, is devouring its own children.’*

There are 5 Sansculottides, and in leap-year a sixth, to be added at the end of Fructidor. Romme’s first Leap-year is “An 4” (1795, not 1796), which is another troublesome circumstance, every fourth year, from ‘September 23d’ round to ‘February 29’ again.

The New Calendar ceased on the 1st of January 1806. See Choix des Rapports, xiii. 83–99; xix. 199.