Home is the most

appropriate birth setting for

most childbearing women.

—World Health Organization2

On the floor of my home—a cabin built “to be ready for the birth”—I have painted a star that marks the spot where my daughter was born. Arriving at four in the morning into her father’s waiting hands, my baby was birthed with an inherent knowing—the ease of an ancient, entrenched familiarity of what-to-do. But most importantly to me—I birthed a healthy baby and I was at home.

I wanted to birth with gentleness. I wanted to make my child’s entry into this world as fluid as possible. I hoped for a seamless transition for her from the internal safe haven of my womb to our awaiting, welcoming environment. I wanted to create and be in control of the atmosphere and surrounding ambiance. Choosing to birth at home granted me this hope.

The desire to bond with this new little being in the comfort of the home she would be raised in was of paramount importance to my partner and me. We wanted her initial smells to be of her mother, her father, her home—to have this sanctuary immediately tangible for her. Our hope was to have her drawn to my breast, umbilical cord still pulsating, and for her eyes to open for the first time to a soft light, rather than the buzz of flickering fluorescents. We wanted to cradle our newborn, rather than have her carried away and bathed instantaneously. My role as mother, and my partner’s role as father, were not to begin once our baby was handed back to us: our desire was for there to be no in-between time.

We were, and are, not alone in this desire. In the Spirit of Home- birth houses a collection of birth stories. These are stories told by people, mainly women, from British Columbia (BC), Canada. Stories by and about women and families who all carried the intent to birth at home. These are stories told by people, mainly women, from British Columbia, Canada—stories about women and families who all carried the intent to birth at home. These are personal accounts shared by those who carried pregnancies under the care of midwives and other nurturing figures.

This collection values diversity and accessibility. It is broadly inclusive, giving voice to those often overlooked or unheard. The pieces range in writing styles and manners of presentation and narrative. There is something distinctly powerful about making the extraordinary ordinary and the ordinary extraordinary. This collection does just that. It is an eclectic mix of stories that illustrates that homebirthing is accessible to (almost) everyone—be you urban, rural, single, or happily married; be you an Amazon or waif, an academic, a high school dropout, black, white, straight, lesbian, or somewhere in-between; be you a polished and poetic writer, or someone who struggles with words. This book prioritizes no one story, nor any one voice over another. And through the sharing of these stories, homebirthing emerges as a healthy alternative for the whole family.

The personal narratives contained in this collection correspond with a movement that is currently raising critical questions about many of the Western birthing practices often associated with hospital deliveries. Questions related to the high rate of cesarean section; the increasing frequency of interventions and the use of machinery; the use of epidurals and other pain-relieving drugs; perfunctory delivery with the laboring woman on her back with her legs in stirrups; and the separation of the baby from its mother after birth. The now-typical hospital birth pays little homage to practices that came before us and were exercised for centuries.

This shift in attitude toward birthing dates back to the early part of the twentieth century, when modernization and cultural trends spurred the discrediting of midwifery care. The consequence has been women largely following an obstetrical approach to birth.

Though it is true that in some cases and places delivering in a hospital may be the safest option due to the particular circumstance—is it appropriate for the vast majority of births? Even the World Health Organization has stipulated that the home, in the majority of cases, is the most appropriate environment for birthing women.3 Still, though midwifery is an ancient tradition of women delivering care unto other women, a tradition dating back to our first cultures, its reacceptance by our modern society at large has been—and still is—taking its time.

Knowledge surrounding the necessity of sanitary and hygienic conditions has improved greatly over the years and made both hospital birth and homebirth safer. Today in the Netherlands, a country with one of the lowest perinatal mortality rates in the world, approximately 35 percent of births occur at home.4 In Canada, however, of the approximately 380,000 women who gave birth in 2011, according to Statistics Canada, only 1.6 percent of those women (just over six thousand), did so outside of a hospital.5 In BC, midwives deliver about 5,500 infants each year or 14 percent of the babies born in the province. Approximately one-third of those babies are delivered at home.6 A large step forward was made in the recent recognition of midwifery in BC. Notable is the adoption of publicly funded coverage for midwifery care by the provincial government. The College of Midwives of British Columbia began registering midwives within the province in 1998. In addition to being able to legally attend homebirths, midwives were also granted hospital privileges at that time, which allowed midwives the right to preside over births within hospitals.

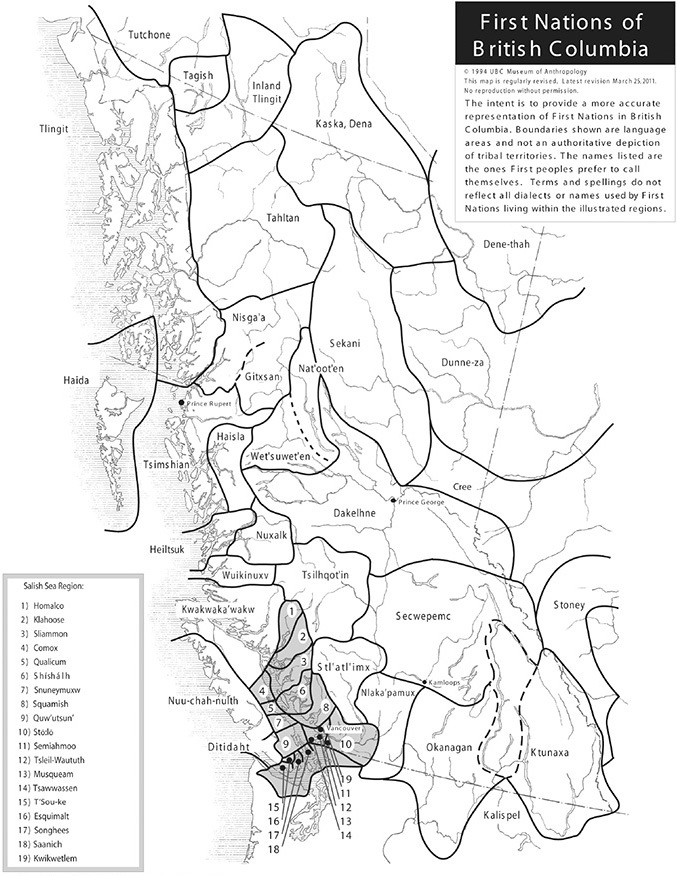

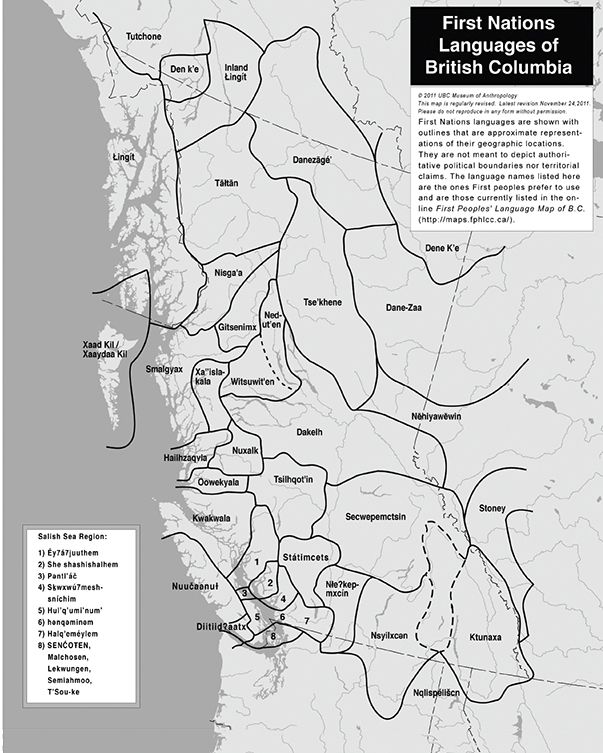

The more than devastating effects of European colonization severely impacted the practice of Indigenous midwifery in BC and throughout the whole of Canada. The National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) reports that in BC, “Aboriginal midwives were charged with passing moral and ethical values from one generation to the next, in addition to guiding the birth process.”7 The same organization shows that removing the birth process from Indigenous communities has had profound spiritual and cultural consequences and is linked to the loss of cultural identity.8 In 2005, the First Nations Health Blueprint for British Columbia, compiled by the BC First Nations Leadership Council, expressed the following:

The mainstream health care system must recognize the unique place of midwifery in First Nation communities and the role of midwifery in the holistic view of childbirth. Midwifery is not accessible to most First Nations women living in poverty or in rural areas. Many of our women are forced to leave home to give birth to their babies in regional hospitals, great distances away from their families. This is a form of neocolonialism that will result in the further loss of our culture, particularly as it relates to the welcoming of new babies into our Nations.9

Movements aimed at reclaiming these losses are slowly emerging. We have seen the establishment of a Committee on Aboriginal Midwifery under the banner of the College of Midwives of British Columbia. Outside of this province, the University College of the North has established an Aboriginal Midwifery program, among other revitalizing initiatives emerging throughout the country.

Though the effects of colonization were and continue to be culturally devastating, there are practices and rituals surrounding birth that have survived and are still practiced within BC.

Though the majority of births in highly industrialized nations still occur under the guidance of doctors, there are emerging trends away from this. Perspectives are changing. Slowly, obstetrical births are coming to be no longer viewed as the only acceptable norm in our society. The acknowledgement that alternatives do exist has contributed to some resurgence of the homebirth and midwifery traditions.

Steps are being made—some small, some large—that can be viewed simultaneously as steps backward in the sense of returning to what was practiced before and steps forward in the sense of making progress. Some may view them as steps that are bringing us full circle. In whichever way these moves are perceived, what is clear is that within the land-base now known as British Columbia, midwives have practiced homebirth for thousands of years, beginning with our First Peoples, and continue to practice in modern times.

Modern women of a// ethnic and cultural descents are reclaiming a birthright: to give birth, and to be birthed, as they have always done. It is an ancient choice . . . yet one that now lends itself to modern twists.

The stories that make up this compilation reveal that other factors can conflict with the initial hopes of expectant parents to birth at home—factors that can result in the need for a medical presence or intervention. These can arise as a result of pregnancy or birth complications, or from a lack of access to local midwifery care. For example, there are currently no registered midwives within BC north of Smithers (located in the northcentral part of the province). This is not to say that there are no practicing lay midwives, or that women in more remote or northern reaches of our province do not opt to birth at home. However, it is clear their options are more limited. Within this volume, people speak to both of these situations: the need for medical intervention, and the lack of access to registered midwifery care.

All the stories contained in this book are viewed equally in a positive light, whether they were successful homebirths or intended homebirths-turned-hospital births. This is not a book of judgments. We are not interested in lambasting the medical establishment. In fact, there is much gratitude expressed in these pages for the prowess of doctors who have helped with complications. I am one of those women. Though I birthed at home, I later had to be transferred to a hospital due to excessive bleeding. For the care I received, I am extremely thankful.

Prioritizing care that best meets the needs of the mother, the new child, and the rest of the family should be the primary objective. To each person this will mean something different. Some women, men, and families feel most comfortable birthing with a doctor in the hospital. Others may opt for a midwife, but in a hospital setting. And for others, comfort during labor may mean something entirely different. We honor and support all of these options and choices. This book focuses on homebirth stories because they are often unheard and deserve to be visible for women who are considering what will make them feel most comfortable and empowered at their time of birth.

This book does not seek to counsel homebirth as the correct option for birth. That is a choice that rests with the individual woman and family involved. The considerations can be complex when making the decision of how and where to deliver. However, this book houses a collection of stories by a diversity of people who all chose and hoped for a homebirth. This is not a book telling you what you should do. Rather, it is a sharing of what this collection of people did do.

In the Spirit of Homebirth seeks to inspire, to inform, to clarify, to highlight, to enrich, to acknowledge, to stimulate, to value, and to engage. These women are redefining a North American “traditional” birth. These stories are finding the new within the old. Further dimension is offered by the reflections of midwives and doulas (from the ancient Greek, meaning “a woman who serves”), and by features about rituals and practices surrounding pregnancy and birth.

From days of labor to babies born so quickly that support did not make it in time, from blissful waterbirths to helicopter evacuations, from planned pregnancies to unexpected ones—a full gamut of experiences is contained within these pages. What they share is a certain set of values. They capture intent.

All of these stories give a sense of the timelessness of birth and reflect the fact that women have been birthing for as long as human beings have existed. I therefore chose not to identify the specific years in which the births occurred—in order to address the essential experience of birthing, which has largely gone unchanged and is not time bound.

The gathering of these stories has been as intriguing and revealing as the accounts themselves. Some of the women I approached had written their stories shortly after the births they described, and they retrieved what they wrote at that time. Others had never written their experience on paper before. For some, this was an opportunity to revisit rich memories. One woman thanked me for prompting her to write her story, stating that she and her husband “fell in love all over again” in the process. For others, the writing of their birth was an emotional event, revisiting, at times, emotions that had been buried. This occurred not only with birth accounts that might be interpreted as traumatic, but so too with some of the births where there were no complications.

The details of how we birth can have far-reaching impacts on how we live our lives from then on. What some women thought would be a straightforward mission to pen their thoughts on paper became instead a significant journey of examining the effects their birth had had on themselves, their partners, their family as a whole, and their lives in general. I read tales of tears, euphoria, joy, and relinquishing. Overall, there was a sense of coming home. What the contributors held in common was an enthusiastic desire to share their stories with others. Each one pointed to the value of hearing and reading other birth stories as a main tool for birth readiness.” It was with this in mind that I initially set myself to compiling these tales—knowing that what I eagerly sought out during my own pregnancy were stories. Ina May Gaskin’s Spiritual Midwifery sparked my desire to create this compilation. Responding to what I, and others, felt was a need for a modern compilation of stories, I set out to gather homebirth stories from within BC, much as the stories from Spiritual Midwifery were all housed at The Farm Midwifery Center and intentional community in Summertown, Tennessee, USA. The project has been nothing short of a deeply enriching and rewarding journey.

This book is offered as a resource for expectant parents, for those who already have children, and for anyone and everyone who can appreciate the marvel of bringing a new life into the world. In the Spirit of Homebirth is offered as an invitation to celebrate these labors of love!

—Bronwyn Preece

Deep roots

The definition of the term midwife varies among different [British Columbia Indigenous] linguistic groups. Among the Nuu-chah-nulth people of BC, it translates as “she can do everything.” The Coast Salish translate it as “to watch—to care,” and the Chilcotin people translate it as “women’s helper.” Whatever the term, the elders recall that pregnancy and childbirth took place within a closely knit nexus linking the midwife to the birthing woman, to the infant, to the husband/partner, to the family, to the extended family and, ultimately, to the entire community.

—CECILIA BENOIT AND DENA CARROLL10

First Nations Map of British Columbia, 2011. Reprinted with permission from the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia.

BC First Nations Languages Map of British Columbia, Version 4-1 Jan 4 2012. Reprinted with permission from the Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia.