Norris M. Haynes

What accounts for disparities in achievement and school adjustment among students, and especially between students in urban inner-city schools and those in more affluent suburban school districts? Social and school context factors appear to contribute more to a variance in school performance than personal and ability factors (Brookover, 1979). Rutter et al. (1977) noted that “schools comprise one facet in a set of ecological interactions and are subject to constraints by numerous social forces they cannot control.” Yet they note that schools have considerable influence on the academic performance and life chances of students.

Sometimes the educator’s view of the student’s world is totally different from the student’s view of his or her own world. Some educators see students in isolation from the rest of their phenomenological world and become constrained in their teaching of and interactions with many students by their narrow focus on the perceived limitations of these students. The challenges and opportunities offered by the urban environment and the positive attributes of the urban learner are often missed or simply ignored. This reduces the effectiveness of these educators and increases the risk of failure among students.

As a social organization, the school develops a culture of its own with norms and standards of behavior. Problems arise when conflicting norms, values, and standards evolve, or are brought into the school by subgroups, and there is cultural insensitivity, discrimination, and intolerance by educators. A cohesive climate in which everyone is respected is the basis for trust, full participation, and meaningful involvement. The evidence shows that a supportive, caring, culturally sensitive, and challenging school climate is a significant factor in the degree of school success experienced by urban students.

THE COMER SCHOOL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

The Comer School Development Program (SDP) was developed in response to the issues and opportunities present in urban schools at the time of its origin: poor school adjustment and low academic achievement among students in troubled schools. Comer’s initial and continuing work attempts to create learning environments that respond to the developmental needs of students in a holistic way. The SDP incorporates and reflects several theoretical perspectives, including the population adjustment and social action perspectives (Reiff, 1966). The SDP resembles a social action model in that it attempts to serve children through social and educational change.

Comer has noted that because of experiences in families under stress during the preschool years, a disproportionate number of working-class and low-income children may present themselves to the schools in ways that are viewed and misperceived as “bad,” showing a lack of motivation and demonstrating low academic potential. In reality, the undesirable and troubling behaviors often indicate inadequate development along any one or more of six critical pathways, to be discussed shortly. Undergirding the SDP is the belief that children who are developing well can learn adequately. Comer believes that positive interactions with meaningful authority figures—parents, teachers, administrators—who support child development simultaneously promote learning; furthermore, reasonable continuity of such relationships is needed.

Critical Developmental Pathways

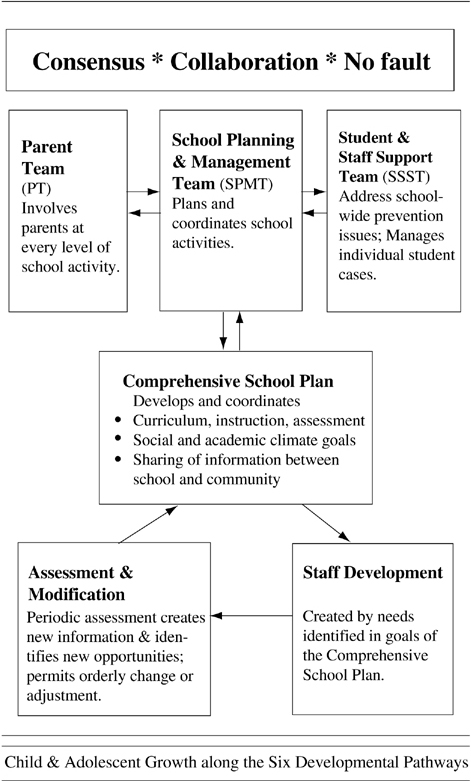

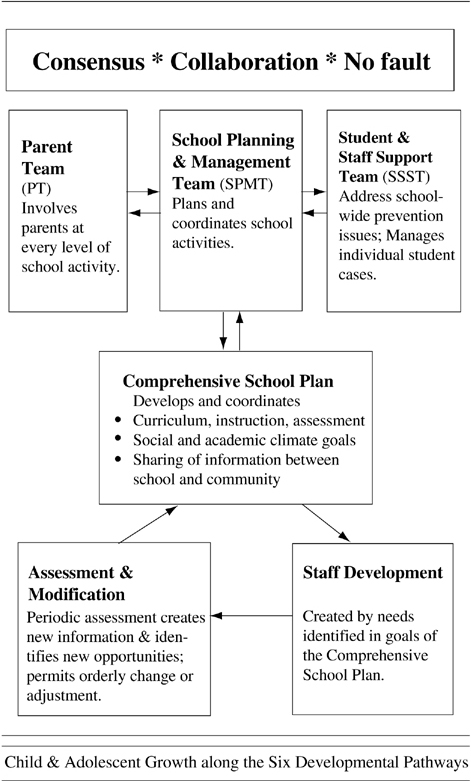

At the core of the SDP is a focus on holistic child development along six interlocking pathways: physical, linguistic, ethical, social, psychological, and cognitive (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 The Nine Component School Development Program: Three Principles, Three Teams, and Three Operations.

Comer identified the need for staff training and preparation in child development and ecological systems understanding (Haynes, 1994). He asserted that many school staffs lack training in child development and behavior management and understand school achievement solely as a function of genetically determined intellectual ability and individual motivation. They may also lack the preparation needed to help underdeveloped children gain proficiency in the basic academic and social skills. Because of this, some schools are ill prepared to modify behavior or to close the developmental and academic gaps of their students. School staff members too often respond with punishment and low expectations. Such responses usually lead to more difficult staff–student interactions and, in turn, to difficult staff–parent and community interactions, staff frustration, and a still lower level of performance by students, parents, and staff. This cycle, most common in our urban schools, must be broken.

The SDP Components

Working collaboratively with parents and staff, the Comer team gradually developed a nine-component framework: three mechanisms, three operations, and three guidelines. The three mechanisms are (1) a school planning management team (SPMT) representative of the parents, teacher, administrators, and support staff; (2) a student and staff support team (SSST), which includes professional staff with child development and mental health knowledge, including school counselors, psychologists, social workers, special education teachers, a school nurse, and others; and (3) a parent program that involves parents at all levels of school life, including participation with staff on appropriate decision-making teams. The SPMT carries out three critical operations: the development of (1) a Comprehensive School Improvement Plan with specific goals in the social climate and academic areas; (2) staff development activities based on building level goals in these areas; and (3) periodic assessment that allows the staff to adjust the program to meet identified needs and opportunities.

Three essential guidelines and agreements are needed: (1) Participants on the SPMT cannot paralyze the principal, and the principal cannot disregard the input of the SPMT; (2) decisions are made by consensus to avoid “winner–loser” feelings and behavior; (3) a “no-fault,” problem-solving approach is used by all of the working groups in the school. Eventually, these guidelines and associated attitudes permeate the organizational culture of the school and transform it into a learning community where child-centered education and learning takes place and sensitivity to child development undergirds all decisions that are made.

EXAMPLE FROM MEYERS PARK HIGH SCHOOL

Following is a case study analysis of the implementation of the SDP at Meyers Park High School, in North Carolina. Michael Ben-Avie, a member of the SDP research and evaluation staff, documented the way the comprehensive School Improvement Plan was developed by the school’s SPMT. According to Ben-Avie (1998, pp. 64–65), the principal at Meyers Park noted the following:

The Comer process allowed the teachers to have ownership of what was going on in the school. The Comprehensive School Improvement Plan was previously designed by four or five teachers when you’re talking about 120 certified staff members at the school and a group of parents, as well as two students. When it was done last year, I took it through the Comer process. I sent a copy of the old plan to all of the committees. We’re going to revise, we’re going to come up with our plan for next year, I said. Give input, change, modify. I sent a copy of the whole old plan to every committee with a memo that asked them to give input to the whole plan and not only their specific area of interest. It was a total staff effort. Once the new plan began to develop, the committees would indicate the portion of the plan that they should be responsible for implementing. Every staff member served on a committee. During the planning process, they voiced issues and concerns that needed to be resolved or incorporated into the plan. While during the planning stage, they began to take ownership of strategies that needed to be implemented. Thus, it was a simultaneous process of discerning what the school needed and ensuring staff buy-in.

I took a tentative plan to the Parent Committee. They gave suggestions, revisions, and so forth. I took the plan back to the staff. The School Planning and Management Team (SPMT) compiled all the input and came up with the new Comprehensive School Improvement Plan. Now, the plan is being implemented by everyone that’s on the staff. In the past, there were complaints about the plan: What was it? What were we supposed to be doing? We voted on the new plan in a faculty meeting and that was it. Now people know what they said needed to be done so they have ownership; they’re doing it. They are turning in quarterly assessments to me so that I can see what strategies they are working on and implementing in their committees.

The story of how Meyers Park developed its Comprehensive School Improvement Plan does not end at this point, however. Just as the school finished its plan, a new superintendent came in and his three goals were literacy, safety, and community/parent involvement. The school went back to the plan. Every single department was able to add strategies that they would use to address these goals.

The Comprehensive School Improvement Plan is a 20-page document outlining goals, objectives, activities and strategies, necessary resources, time lines, responsible persons, and evidence of completion. Goals range from increasing communication between home and school to improving literacy. As the Comer process was implemented, the school community discussed strategies for increasing the enrollment of students placed at risk in the school’s behavior improvement program. A department chair had been given an extra planning period to develop a support group to keep the at-risk students involved in the program and to work on recruitment. In the Comprehensive School Improvement Plan, goals aim to ensure that curriculum and instruction meet the full range of educational needs in serving a wide range of students. The objectives listed under this goal include using student data for planning, increasing the media center’s support of the teaching–learning process, continuing to develop alternative programming to meet the diverse needs of students, and implementing special programs and courses to address the diversity of the student population.

At the January 7, 1997, SPMT meeting, the team discussed contacting parents of students who were at risk of failing. At the high school level, a student could have between six to eight teachers (and sometimes more if physical education and other activities were counted). A teacher, they decided, is to initiate contact with the student’s guidance counselor via a form developed by the Research Committee. The guidance counselor has the perspective to see whether the student is in danger of failing only one class or several. The guidance counselor would notify the parents and talk with them about their child’s overall progress at school.

The SPMT next met on January 23. The team discussed the importance of considering each other’s feelings and avoiding “finger pointing” during meetings. They agreed to allot an approximate time for each topic on the agenda to avoid digressions, to make every effort to meet the following year during fifth period (instead of after school) when people tend to be more alert, and to keep in mind that they represent groups, not themselves personally. During the meeting, the team heard about the progress of the tutoring program. Thirty-five tutors had been trained. Teachers were asked to provide the tutors with adequate materials and detailed objectives to ensure the program’s success. Staff and parents complimented the Comer committees for having done a great job in supplying hard-copy evidence that they had been implementing strategies to improve the school.

In reflection on the SDP and the changes at Meyers Park, Lloyd Wimberley, a staff member observed: “a high school can be pulled in so many different directions at the same time. It’s a very complex and very differentiated kind of organization. The SDP creates a common language. It creates a common view that is student-centered. This helps us get on the same page together and realize the common interests.” (Ben-Avie, 1998, p. 65)

EFFECTS OF THE COMER SCHOOL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM

The SDP has had multiple and significant effects on aspects of students’ social, emotional, and academic development.

Analysis of data from studies in New York, New Haven, Chicago, and other school districts indicates significant program effects on student achievement. Many schools where the SDP has been implemented successfully experience significant student academic growth on standardized measures of achievement, including state criterion referenced tests and norm referenced tests (Haynes, 1998). Data also indicate that school-related attitudes and behaviors are also positively affected. There have been significant decreases in absenteeism, suspensions, and referrals for disciplinary problems (Comer, Haynes, & Hamilton-Lee, 1988). Studies on SDP effects on social and emotional development showed that the program has had a positive effect on students’ self-concept, feelings of efficacy, motivation to achieve, and their social competence (Becker & Hedges, 1992; Cauce, Comer, & Schwartz, 1987; Cook, 1998; Haynes, 1994; Haynes & Comer, 1990, 1993).

Policy Implications

The work in the SDP has significant implications for the reformulation of national education and social policy and the refocusing of educational practice across the United States. Over the past decade, and recently with the national focus on systemic school reform, Comer and his colleagues have informed and in some cases led the debate about what true educational reform means and what it must entail. They have asserted time and time again that genuine reform in education must focus on addressing a number of key issues. These include the following:

FINAL THOUGHTS

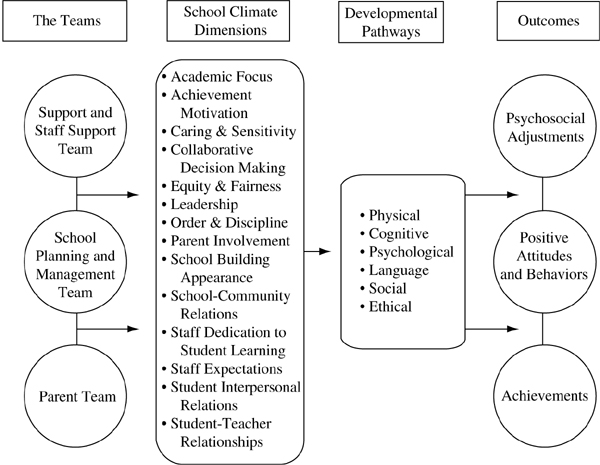

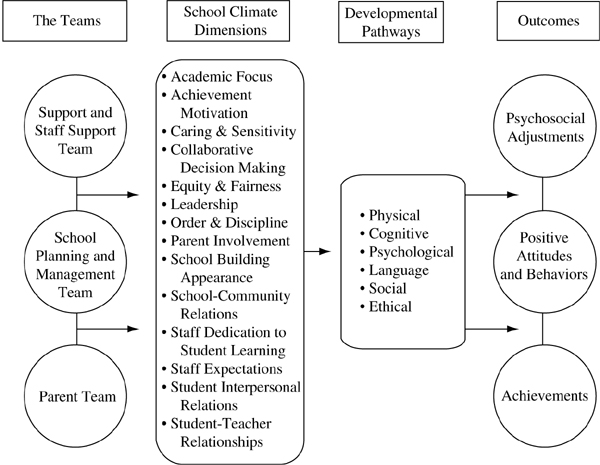

The evidence clearly suggests that when the Comer SDP is implemented well, it improves school and classroom climate and enhances students’ academic and social behaviors (see Figure 9.2). The SDP is an effective process for improving schools. It is not a magic solution, but a commonsense approach to school reform that is grounded in sound child development principles. Our continuing documentation shows that significant positive effects on school and student performance outcomes are achieved with successful implementation of the Comer SDP. The growth trajectories among the lowest achieving schools that adopt, and consistently and faithfully implement, the Comer SDP support the view that a student-centered, developmentally sensitive approach works. Sustained change and commensurate positive student outcomes result from continuous dedication and renewal of commitment among all of the adults in children’s lives. Such efforts transform schools into caring, sensitive, and challenging learning and development communities.

Figure 9.2 Effects of the Comer School Development Program.

REFERENCES

Becker, J. B., & Hedges, L. V. (1992). A review of the literature on the effectiveness of Comer’s School Development Program. New York: Rockefeller Foundation.

Ben-Avie, M. (1998). The School Development Program at work in three high schools. In N. M. Haynes (Guest Ed.), Changing schools for changing times: The Comer School Development Program [Special issue]. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 3(1), 53–70.

Brookover, W. (1979). School social systems and student achievement. New York: Praeger.

Cauce, A. M., Comer, J. P., & Schwartz, D. (1987). Long-term effects of a systems oriented school prevention program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 127–131.

Comer, J. P., Haynes, N. M., & Hamilton-Lee, M. (1988). School power: A model for improving black achievement. Urban League Review, 11, 187–200.

Cook, T. (1998). Report on the Comer Process in Prince Georges County, Maryland.

Haynes, N. M. (1988). School Development Program: Jackie Robinson Middle School follow-up study report. New Haven, CT: Yale Child Study Center.

Haynes, N. M. (1994). School Development Program SDP Research Monograph. New Haven, CT: Yale University Child Study Center.

Haynes, N. M. (Guest Ed.). (1998). Changing schools for changing times: The Comer School Development Program [Special issue]. Journal of Education for Students Placed At Risk, 3(1).

Haynes, N. M., & Comer, J. P. (1990). The effects of a school development program on self-concept. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 63, 275–283.

Haynes, N. M., & Comer, J. P. (1993). The Yale school development program: Process, outcomes and policy implications. Urban Education, 28, 166–199.

Haynes, N. M., Comer, J. P., & Hamilton-Lee, M. (1988). The school development program: A model for school improvement. Journal of Negro Education, 57(1), 11–21.

Reiff, J. (1966). Mental health manpower and institutional change. American Psychologist, 21, 540–548.

![]()