Football arrived in Brazil with Charles Miller and his two balls. Or so the official story goes. Well before the first kick-about, however, an Indian tribe was playing a game that consisted of football's most cerebral element. German explorer Max Schmidt was one of the first witnesses. Trudging through the rainforest, he came across a crowd of Pareci Indians playing with a ball made from the rubbery sap of the mangaba tree. Two teams were facing each other, bouncing the ball back and forth using only their heads. The game had 'no ceremonial meaning, being just of sporting character', he jotted in his notebook. In 1913 the swashbuckling former US president Theodore Roosevelt journeyed through the Amazon. It is said that he saw nothing on his entire trip that caused him such pleasure as the Pareci's game, which he christened 'headball'. News of the indigenous sport reached Rio de Janeiro, provoking great curiosity. One newspaper suggested it would be interesting to invite the Pareci to Rio: 'Interesting and original. Original, especially – which is already something.' Entering the vigorous debate about whether or not football was too European to be a positive influence in the tropics, 'headball' – if nothing else – was at least authentically Brazilian.

Sixteen Pareci eventually fulfilled journalists' wishes and travelled 1,200 miles from their village to play an exhibition match. The visit, in 1922, was treated like an important sporting event. Fluminense offered their stadium, Rio's largest, which only weeks before had hosted the South American football championship. The Indians slept in tents put up on the pitch. Press coverage fuelled an 'extraordinary interest' in the game, now given its indigenous name, zicunati.

The match took place on a Sunday afternoon for maximum attendance. It was staged with the pomp and ceremony of a football international. In front of a packed stadium the Pareci entered the pitch. Dressed in scout uniforms and with their hair brushed to the side, they looked more like Eton schoolboys than Stone Age savages. The absurd scene carried on when they sang, in their own language, their 'national anthem' – upon which the terraces hooted with laughter. After retiring to put on their football kit, they returned as two teams, eight in white tops and seven in blue. The sixteenth member, who had been feeling unwell when the party arrived in Rio, had since died.

The teams stood at either side of a central line. The Indians headed the ball between each other, gaining a point when the opposing side failed to head the ball back – rather like volleyball. Rallies lasted a surprisingly long time. The Pareci jumped, ran and dived, greatly impressing the Brazilians with the speed and agility displayed. As the match progressed, the crowds got the hang of the rules and they started to cheer on the teams – much to the Indians' terror and confusion.

Newspaper reports described the event using football terminology, as if dressing zicunati in football's clothing somehow conferred an urban modernity. On scoring a point the winning team 'shouted between themselves in an extremely original way – like any other goal celebration', noted the Correio da Manhã. After two thirty-minute halves the white team narrowly defeated the blues by 21 to 20. 'Zicunati is not at all violent,' wrote one journalist. 'It doesn't even have the fouls and charges common in football. It's a game exclusively for the head.'

O Imparcial devoted its front page to an interview with 'major' Coloisoresse, the Pareci chief.

You must certainly be very tired?

No. This was nothing. It only lasted an hour. Back home we play zicunati every morning from Sam to 11am, and in the afternoon

from 1pm to 5pm. It's our favourite pastime . . . Today was strange for us. All this stuff with boots, shirts and shorts –

they just get in the way! The turf gets in the way too because it's slippery. Where we come from we have large pitches carefully

prepared for zicunati with no grass at all.

The exchange seems less a comment about heading practice in the jungle than a parody of the growing obsession for football

in Rio in the 1920s. One wonders, for example, when the Pareci have time for dull chores like hunting and gathering. Unsurprisingly,

zicunati did not catch on. The Indians trekked back to their village. About 1,300 Pareci still live near Rondonia-Mato Grosso

state border. They carry on making zicunati balls from mangaba latex, and play the sport enthusiastically among themselves.

***

The next native contribution to Brazilian football came in 1957, when a player called Índio – Indian – was instrumental in qualifying Brazil for the following year's World Cup. He scored in the first qualifying game (Peru 1-1 in Lima) and was fouled in the second (Peru in Rio), earning a free kick that resulted in the game's only goal.

Índio gained his nickname because he looked like he had stepped out of a Western. In Brazil if you look vaguely Amerindian – having straight hair and dark skin is often more than enough – then it is a moniker you have a good chance of earning. Because miscegenation occurred on such a large scale, there are many, many Índios. More than twenty have been registered as professional footballers at the Brazilian Football Confederation in the last decade.

At least one of them is genuinely indigenous. The Índio whose real name is José Sátiro do Nascimento was born in an Indian community where his father is the tribal chief. He is twenty-two years old and a right back at the São Paulo club Corinthians. I watch a morning training session at the club ground, and chat with him afterwards in the dugout.

Índio's life is one of the most remarkable journeys in football. Brazil's Indians are at the bottom of the social ladder – poor and excluded, fearful and distrustful of the outside world. Índio managed to reach the top, becoming the first indigenous player to play not only for a big club but also the national team. 'I never thought I would be a footballer,' he says. It's a cliche but you really believe it. 'I used to work on the harvest. Planting watermelons, that sort of thing. My family had no money for anything. We were always going hungry.'

Dressed in his training gear, Índio looks like any other footballer. His thick, black hair is cut short and lightly flicked. Indian features like delicate oriental eyes, high cheekbones and a strong, triangular nose are not uncommon among Brazilians. Differences are clearest off the pitch. São Paulo, a concrete sprawl of eighteen million souls, does not offer him pleasures. Unlike most successful footballers, who live with their wives and young children, Índio lives alone with his agent. He went to the cinema once and did not like it. 'My life is staying at home and coming to train.' He speaks very fast, in staccato sentences, as if he is reciting a list of prepared statements. He tells me his favourite pastime is going to the shopping mall and eating ice cream. 'Indians don't like cities. We like the bush. It's difficult here.'

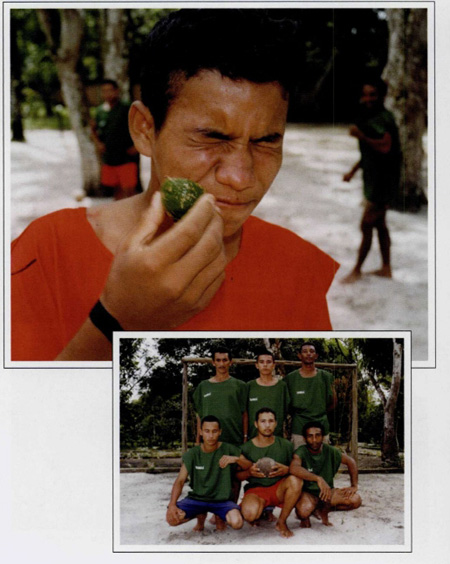

As a child growing up in the semi-arid northeast of Brazil, Índio played football with anything circular, even coconuts. 'The green ones don't hurt your feet. We were used to it anyway. I never played football with a proper ball.' His first team was a small amateur side from the settlement where his family were living. The settlement was separated but not isolated from the developed world. In 1995 he was noticed by a scout and sent to Vitória, a first division club in Salvador well known for its youth development work. It was the first time he'd travelled, the first time he saw the sea. 'What a big river,' he thought.

The culture shock was almost too great to bear. He found the food inedible. 'At home we ate snake, all that sort of thing. Anything we could hunt we would eat. Meat, fish, we ate quite a lot of that there – but we ate without spices. At Vitória it was really, really difficult to adapt. The food was very different. I thought it was weird, really strong.' Once he ran away. He laughs. 'I wasn't able to eat that food that they made there any more, I couldn't bear it, I went back home. But Vitória came and got me and took me back.'

Staying in football meant giving up the claim to succeed his father as chief of his tribe. It paid off. In 1996 Vitória's junior team played Corinthians in São Paulo and he was transferred. He made his first-team debut two years later and was called up for the national under-21 side. Índio is now his family's only breadwinner. He supports about forty relatives. 'Where I am from everyone is going hungry. I suffered together with them. I'm not going to let them carry on suffering,' he says. He has housed them in a town 180 miles from São Paulo. 'It's difficult to keep in touch because they don't have a telephone. They don't have money to call me all the time, and I'm in the team hotel a lot.' He used to have a mobile phone, but he broke it because his family called it incessantly on reverse charges.

Índio's promotion to the Corinthians first team coincided with winning the 1998 Brazilian league title, a feat repeated the following year. He played in the team that won the World Club Championship in 2000, but since then has struggled to keep in the side. 'He is inconsistent,' says Fábio Mazzitelli, who covers Corinthians for the sports daily Lance!. 'He seems unable to hold a place. Maybe this is something to do with his upbringing – perhaps it shows a lack of confidence.'

Insecurity is not a surprise considering his family's tormented history. Six months before I met Índio I had visited the village where he was born, in Alagoas state. I took a taxi from the capital, Maceió. For the first part of the two-hour journey the fields were full of sugar cane and the air smelled of molasses. The scenery turned more savannah-like until Palmeira dos Índios, where deep greenery reappeared. We entered the town and drove out of it on an uneven track. There were no signs of human activity until the road forked and on the left was a simple brick house.

An elderly woman appeared in a T-shirt and knee-length skirt. I said I was looking for the family of Índio, the footballer. 'He's my grandson,' she replied, and invited me in.

Flora 'Auzilia' Ferreira da Silva is sixty-eight and lives on her own. She sat me on a hard wooden sofa. Her possessions do not stretch to much more than an old television and an antique hi-fi. Indian tribes that have had contact with colonisers for hundreds of years tend to live in homes that copy the way non-Indians live – the main difference is that they are significantly poorer.

A quick glance around the room and I saw no indication that she was related to a famous sportsman – no team poster nor autographed photograph. Several passport photos of her grandchildren were wedged in the frame of a fading colour portrait of her and her daughter. I recognised Índio. The only other image of him was on a badge with a blue border. 'Here's my handsome,' she said clasping it proudly.

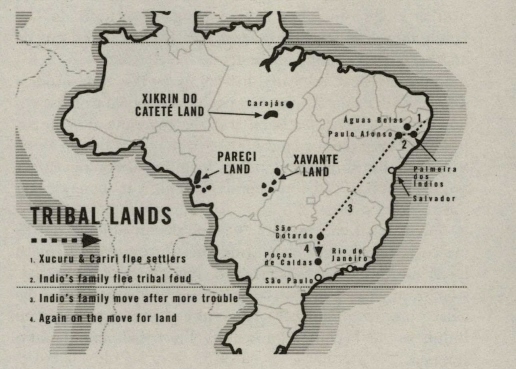

Auzilia told me the family's tragic story. Her daughter Josefa married Chief Zezinho, leader of the Xukuru-Cariri. Josefa was fourteen when she had her first child, which died aged two months. Her second also died in infancy. The third, a boy, survived and the fourth was Índio. A feud within the tribe left one man dead and Chief Zezinho accused of his murder. He was forced to leave. Neither he, Josefa or their children have been back since.

The situation of Índio's tribe illustrates the main issue concerning Brazil's Indians – their fight for land. When the Portuguese arrived in 1500 the Xukuru and the Cariri lived on the coast of what now is Pernambuco. With the colonisers' arrival, the Indians settled in jungle near where Auzilia lives today. In the middle of the eighteenth century, pioneers, seeing that the Indians had the best land, set fire to the trees to try to get rid of them. The Indians suffered persecution, slavery and death.

Forced to live in reduced areas and share almost nonexistent resources, the Indians started to fight among themselves. About 2,000 Xukuru-Cariri lived near Palmeira dos Índios. After the bloodbath of 1986, Chief Zezinho began an odyssey looking for a home for his family. He first went to the National Indian Foundation in Brasilia, cap in hand. After several changes of address they finally ended up 120 miles away from Palmeira dos Índios, near the town Paulo Afonso, on the banks of the River São Fransisco. They lived there for over a decade until another bloody episode. Índio's brother killed a man in a row over a game of football. The family moved again, 900 miles to the south – helped out by another group of itinerant Indians, the Atikun.

Índio has since relocated his family to Poços de Caldas, on the São Paulo-Minas Gerais border. Having given up hope of being given territory from the government he hopes to buy a large plot of land for the tribe to live on. He says: 'I spend a lot of money on all of them but I won't even get bothered about it. It's my family. I think it is money being put to good use.'

The inconsistency in Índio's game that is pointed out to me costs him his job at Corinthians. A few weeks after I interview

him, he is transferred to Goiás, a smaller first division team, based in the savannah city Goiania. There he asserts his identity

further – Goiás already has a player called Índio, so he becomes known by his tribal name, Índio Irakanã.

Índio's emergence is a direct consequence of recent changes to the Brazilian government's Indian policy, I am told by Fernando 'Fedola' Vianna. In 1988, Brazil's constitution recognised for the first time that Indians had rights to the land that they traditionally occupied. 'The Constitution changed the view that Indians should be colonised to an acceptance that Indians should be Indians,' he says. Even if every tribe has not yet won back its land, like the Xukuru-Cariri, the Constitution instilled a sense of solidarity and pride among its indigenous population. 'It meant that Indians were not ashamed to be Indians any more. I wouldn't be surprised if many more Índios appear in the future. Discriminated parts of the population have traditionally found in football a way of climbing through social classes.'

Foroe kings

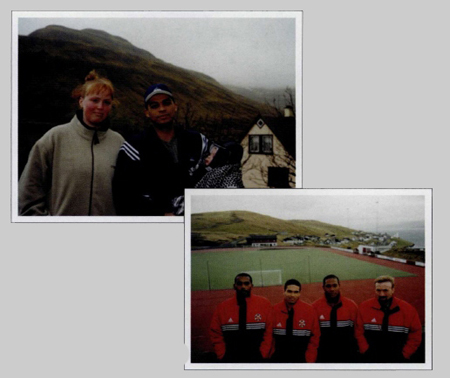

Top: Anja, Robson and baby Mateus outside their home in Gøta. Right: Messias Pereira, Marlon Jorge, Marcela Marcolino and B68 president Niclas Davidsen in their club uniforms. Behind them is Toftir.

prodigal sun

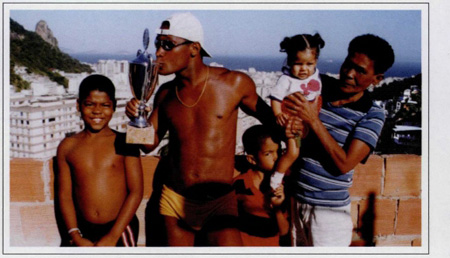

Back in Rio, Marcelo Marcolino kisses the trophy he won as Best Forward in the Faroese League. He is together with his mother and family, on the roof of their brick shanty overlooking Copacabana.

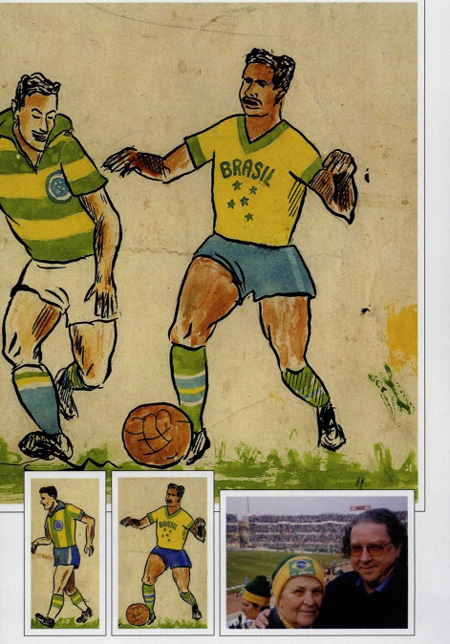

cartoon strip

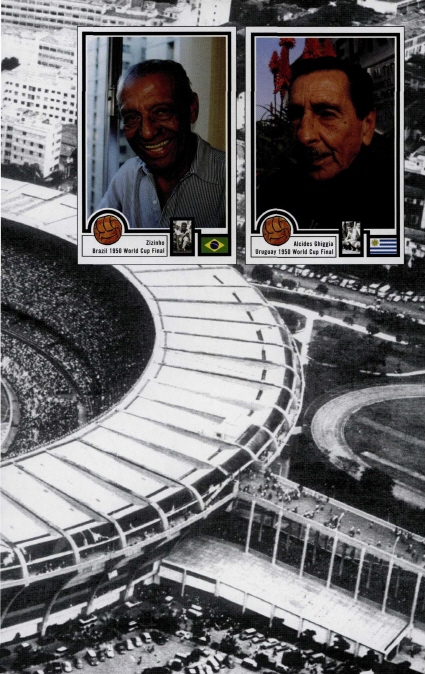

Top: The sketches Aldyr Garcia Schlee drew before he designed the Brazilian football kit. Near right: The first and fourth figures digitally restored to their original 1953 colours. Far right: Aldyr and Marlene in the Centenario Stadium, Montevideo, to watch Uruguay vs. Brazil. Previous page: The Maracanã stadium, Rio de Janeiro.

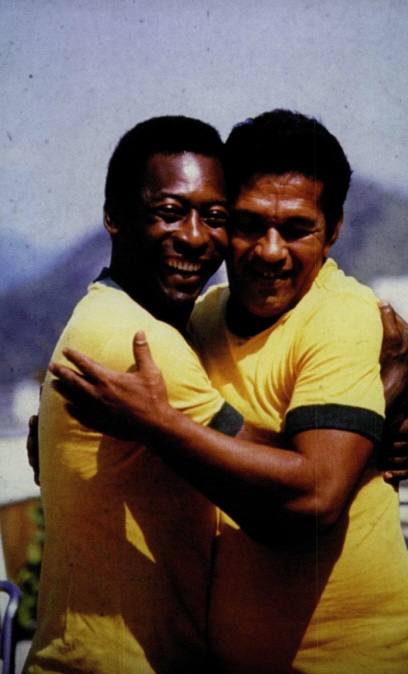

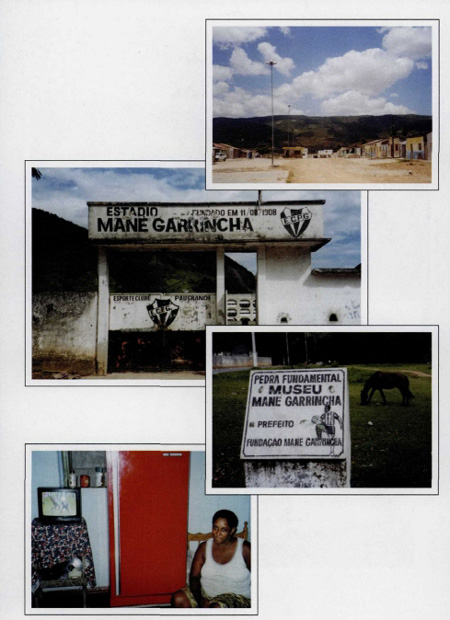

birdlife

Top right: The Fulniô village square at Águas Belas during the Ouricouri. Top left: The stadium of Esporte Clube Pau Grande, Garrincha's first club, now named in his honour. Bottom right: The first – and last – stone of the Garrincha museum. Bottom left: Nenel, Garrincha's daughter, in the room which is her home. Left page: Brazil's two most famous footballers two months before Garrincha's death.

good hair day

Top: Cotton Bud relaxes with two admirers at the 1998 World Cup in Paris. Middle: A younger Cotton Bud in Italy in 1990. Bottom: Guilhermino, one of Fluminense's symbol-fans. He covered himself and his fans with talcum powder for decodes.

feathered friends

Top: Big Carl and his favourite English journalist, during the 2001 carnival. Middle: The Hawks at a football stadium with one of their smaller banners. Bottom: The opening float in the Hawks' 2001 parade.

knees up buttons down

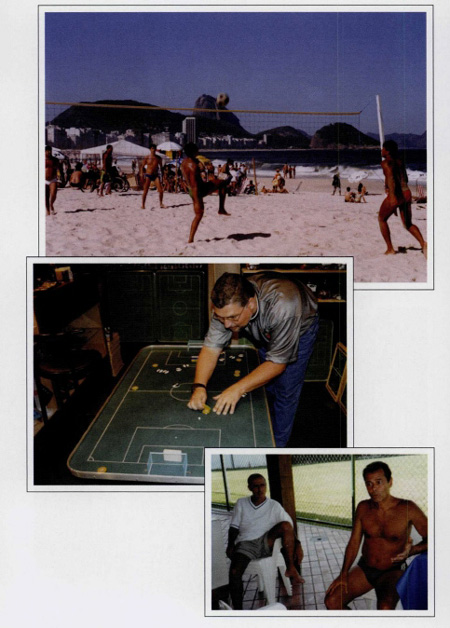

Top: Footvolley on Copacabana beach, in view of the Sugar Loaf Mountain. Middle: Marcelo Coutinho practising free kicks in the Button Office. Bottom: Poulinho Figueiredo dictating the conversation at his private society pitch.

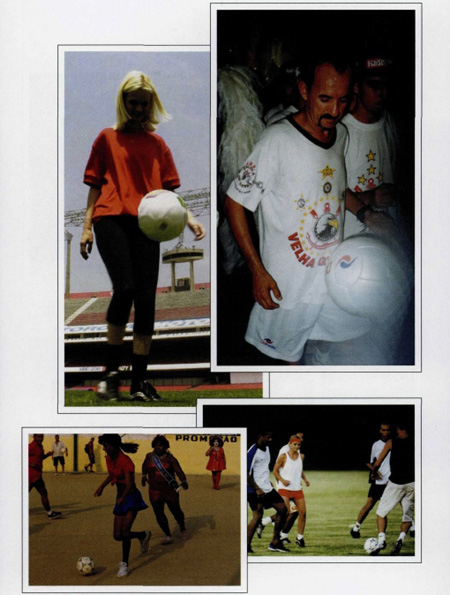

men and girls (and those inbetween)

Clockwise from top: Zaguinha arrives at the end of the São Paulo carnival parade without the ball having hit the ground. Milene Domingues sweating out her marriage with Ronaldo (second right), with a little help from Vampeta (second left). Roza FC penetrate the heterosexual opposition. Claudia Magalhães hard at work.

sour times

After a close shave with the pupunha tree, a dribble around the jackfruit tree, the young ecoball striker collided with the mango tree. He was sent off by the referee and ordered to suck a lemon. 'The more you suck the sicker you get,' he complained. 'It affects your game.'

We are speaking in the Instituto Socioambiental, a well-respected Indian rights organisation that is based in a grand colonial house in central São Paulo. Up several flights of a wooden staircase there is an open-plan office full of fashionable young anthropologists in jeans and colourful T-shirts. Fedola has an occupation that is the fruit of conditions found uniquely in Brazil. He is a football ethnographer – a former professional left back turned academic who researches the game among indigenous communities.

Brazil has 216 Indian tribes, and possibly a dozen more who have not yet been discovered. They make up about 350,000 people. They speak about 180 languages. Their villages stretch from the Amazon jungle to the semi-arid northeast and the pampas of the far south. As a 'nation' Brazil's Indians are geographically and linguistically isolated and economically and politically weak. One of the most visible ways in which links between the tribes has been strengthened, says Fedola, has been through sporting events.

In the mid-1990s states with large Indian populations started to hold inter-tribal sporting competitions. The model was copied for the first Indigenous Games in 1996, which united Indians from all over the country. The third Indigenous Games, in 2000, had more than 600 athletes. The games include less well-known sports such as shooting with zarabatana blowpipes, running with a tora treetrunk and huka-huka wrestling. But by far the most popular event is football. In the same way that different tribes speak to each other using Portuguese, their second tongue, football provides a sporting common language.

Top of football's indigenous ranking are the Xavante – a tribe of about 10,000 from the state of Mato Grosso. They are the 'Brazil' of the Indian population, having won football gold at all three Indigenous Games. Fedola's research focussed on a remote village of 80 Xavante, where he lived for two months. He discovered that football has such an intense presence that it shapes the village's internal structure and external relations. 'Indians in the village play between themselves, villages play each other and indigenous territories comprised of several villages play other territories,' he says. 'On match days whole villages squash in the back of a truck to travel to an away game. The village hosting the match also puts on parallel non-football activities, such as feasts and political meetings. Football stimulates this type of social exchange, which otherwise might not go on.' Fedola adds that one of football's strengths is that the tribe believes it may help them integrate into urban Brazilian life.

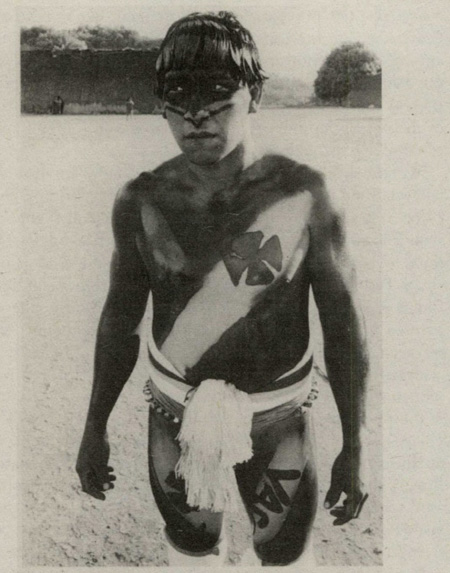

A Kuikuru Indian flaunts Vasco's strip in bodypaint

It is estimated that football reached the Xavante in the 1940s or 1950s. Modern legends surround the tribe's footballing prowess. In the 1970s a team of Xavante visited the Mato Grosso capital, Cuiaba, to play the junior team of a good Cuiaba club. The Indians, 3-0 down at half-time, turned the game around and won 5-3. Years later an Argentine missionary spoke to a member of the defeated team. 'You let them win, didn't you?' he asked. The man replied: 'Not at all. We couldn't keep up.'

Brazilians typecast Indian footballers. A player who constantly attacks in random directions and never defends is said to 'play like an Indian' – although this probably has more to do with Hollywood 'injuns' than indigenous South Americans. Indians are also unfailingly described as tireless and speedy. This stereotype, however, has some scientific backing. In 1997 a team of twenty-five footballing Indians from thirteen tribes underwent tests at São Paulo Federal University's Centre for the Medicine of Physical Activity and Sport. The results showed that the Indians' cardiorespiratory capacity was 10 per cent greater than the average for a professional footballer. In layman's terms, they have more puff. Indians are also stereotyped for not being competitive enough. Fedola believes this prejudice may hold a grain of truth. 'Even though the romantic idea that Indians just play for fun is a myth, I think that the importance they place on victory is less than for us. They say: "we've lost today but tomorrow we'll win."'

In 1996 Fedola visited the Xikrin do Catete, who live on the southern fringes of the Amazon rainforest. Perhaps he should have guessed something was afoot when he saw one Xikrin go about his daily life in studded football boots-Indians are usually barefoot or wear flip-flops. The Xikrin knew about Fedola's sporting past, and they asked him to teach them football warm-up exercises. 'I think they already had an idea what the exercises were, but with me being there they wanted to know more.' The ex-pro showed them basic techniques, such as skipping on the spot and making sideways strides. Fedola gets out of his chair and demonstrates. They are instantly recognisable moves.

Three months after Fedola's visit the Xikrin performed a large ritual in the centre of their village, which is surrounded by a circle of small brick homes. The ceremony began at dawn. Two flags were raised – one of Brazil and one of the National Indian Foundation. An Indian read aloud lines from the Bible in the tribe's native language, Kayapo.

Observing the proceedings was Isabelle Giannini, an anthropologist who has studied the Xikrin since 1984. She had seen many similar ceremonies. They customarily involve two parallel lines of young Indian men wearing feathers and traditional dress. This time the two lines were dressed in football kit, each line in a different colour. Strange. The men started to dance. 'I nearly burst into tears,' says Isabelle. 'They were sprinting in zig-zags, lifting up their right legs and then their left.' The ritual's dance was a choreography based on Fedola's excercises.

I ask her if her tears were of sadness. She says not at all. She says she was overcome with joy. Rather than seeing the football dance as a denigration of ancient customs by modern culture, she felt it showed the strength of Indian traditions to adapt to new realities. 'I thought: "Good on you Indians! You are here to stay! You will carry on being Indians!"'

She adds: 'The ritual is about understanding the Xikrin's position in the cosmos. It is about showing that they are in control

of their world. Which is a world that includes football. They appropriated elements from our society and have incorporated

it on their own terms.'

***

The first Indigenous Games football final ended with a 2-1 win by the Xavante over the Fulniô. The losers claim they were robbed. The Fulniô steamrollered through the opening round with victories of 11-0, 8-0 and 3-1. But the squad had not counted on competing in the swimming, athletics and volleyball too. Unlike the Xavante, who rested for three days before the match, the Fulniô could barely stand up.

In October 2000 I visit the Fulniô, who live about fifty miles from Palmeira dos Índios. Like most Indian groups near Brazil's urban coastal strip, the Fulniô are almost completely assimilated to modern culture. They live in a village of brick homes that is separated from the small town of Aguas Belas by a belt of wasteland. The Fulniô village looks like a poor, miniature replica of the adjacent town. Both radiate from a square headed by a Catholic church. But whereas Aguas Belas' streets are asphalted and its shops cluttered with clothes and hardware, the Fulniô streets are irregular paths of earth. The only commerce apart from the bakery is craftwork in the Indians' homes.

I arrive at the Fulniô village shortly after sunrise. Homes are empty. Streets are deserted. It has the haunted feel of a defunct film set. I drive around and notice that among the fading pastel-fronted bungalows only three buildings have recently been painted: the local office of the National Indian Foundation, the bakery and the football team, Guarany Esporte Club.

None of the Fulniô have slept in the village that night because we are in the period of the Ouricouri, an annual ritual in which the population moves, en masse, to a secret retreat. The hidden camp is three miles from the town, down an orange earth path, shortly beyond a sign that reads: 'Do Not Enter – Danger – Indian Tribe.' Only the Indians know what happens at the Ouricouri. The Fulniô joke, half seriously, that if any non-Indian is found within the gates they will have no option but to kill them. The ritual is the strongest expression left of their traditional culture.

An hour later the square springs to life. An old truck pulls up and a handful of people jump out. Dozens more arrive shortly afterwards in overloaded cars, on motorbikes and on bicycles. The village is suddenly abuzz.

During the Ouricouri, only a few activities are considered important enough to leave the retreat: school, essential errands and football practice.

I make my way to the corner of the central square where Guarany's players are gathering. Someone passes round an ornate wooden pipe stuffed with rolling tobacco. 'Instead of taking a juice in the morning, we smoke this,' he jokes. We walk through the village to the pitch, passing through a rubbish tip. A donkey walks past the goal before Guarany start their practice. The session is eleven-a-side. Ronaldo Cordeiro, the coach, is refereeing barefoot. The others have boots with plastic studs that scrape across the dried earth.

Ronaldo, an intense man with a booming nasal voice, likes to point out Guarany's stars. Several have played professionally for small clubs in the northeast and centrewest. 'He played in Pernambuco. That one was wanted by Flamengo. Many people liked him but he drinks a lot of cachaça*,' he lists as he points around the team.

Essy-a, a twenty-three-year-old attacking midfielder, started his career as a junior at first division Recife side Sport. He then had stints at Olária in Rio de Janeiro, Colo Colo in Ilheus, Bahia, and Anápolis in Goiás – a round trip, as the crow flies, of 3,300 miles. He said he delayed the opportunity to play for a provincial Rio side in the national league until the New Year. 'I prefer to stay here for these months because of the Ouricouri.'

'That's the problem,' interrupts Ronaldo. 'Indians are not equipped to take advantage of these opportunities. We aren't used to being far from home. Indians like to be free. We don't like responsibility. An Indian would always prefer to be messing about here, smoking his pipe.' Ronaldo, who is forty, is given an air of seniority by a pair of sunglasses attached to his head with string.

The Fulniô are good at football and they know it. The tribe has 3,000 people and three football teams – Guarany, Palmeiras and Juventude. The Fulniô have one-tenth the population of Aguas Belas – yet the Indians' teams are much better than the town's clubs. 'We show our superiority through football,' Ronaldo says. 'There used to be a championship between us and them but there hasn't been for a while because there's no point – we always win.'

Afterwards, I check this out and find it to be true. The Fulniô are known around the region as an excellent side. Their reputation is high in the nearest city, Garanhuns, sixty miles away. After the Indians compete in local tournaments, Garanhuns' teams pick off the best players. AGA, one of the city's two professional clubs, has a Fulniô right-winger, reassuringly named Índio. Alfredo Faria, AGA president, praises Índio's stamina with a deferential sigh. 'He runs up and down the field all ninety minutes and then, after the game, he runs twenty times around the pitch. Indians' strength is that they have a certain physical vigour. It's in their genes. Ask Mother Nature.'

At the training practice, Ronaldo tells me that the Fulniô are fast. 'We learn about speed when we go hunting chameleons. The Indian has to do things fast because when he hunts he has to bring things back straightaway. Because speed comes from our tradition we don't want to lose it. We also eat strong food. Meat. Fish. And we're used to the hot sun.'

Ronaldo invites me to his home, a brick bungalow with a tiled roof. He has moulded the Guarany crest in cement on the front wall of his house 'because it's a way of it never ending. Guarany changed our community.' The club's initials are in a green circle bordered at each side with an arrow. 'The shield shows both the sporting and the Indian side,' he says. We cannot talk long because he has to get back to the Ouricouri.

I am impressed by the seriousness with which the Fulniô take football. It is not a recent phenomenon. Guarany was founded in 1952. Later, I speak to Blandina Spescha, regional coordinator for the Indian charity Cimi. She agrees that football has become an aspect of the Fulniô's identity: 'Every oppression has a reaction, and many times this reaction is through sport.' Football is particularly empowering because it is the sport most valued in Brazil. Sister Leopoldina de Sousa, a Franciscan nun who lived in the community for two years, adds that football inadvertently strengthens tribal traditions. 'It is a valuable way for the men to demonstrate their masculinity. It really does give them self-confidence,' she says. Football boosts Indian culture in other ways. Fulniô teams confuse non-Indian opposition by shouting commands to each other in their language, late, which in daily life is losing out to Portuguese.

According to Sister Leopoldina, whenever there's a big match on television the Fulniô 'take the day off. Crowds gather in the few homes that have televisions. Ronaldo has tragic personal experience of the Indians' fervour. 'My brother died of a heart attack when Brazil played Holland [in the 1998 World Cup], and Leonardo's goal was disallowed.'

A peculiar physical trait of some – maybe a dozen – Fulniô footballers is bent legs. Not the ideal sporting profile. But the defect is used to their advantage. One midfielder, swears Ronaldo, is impossible to tackle. His shins skew divergently from his knees, forming a ball-sized gap between his feet when he stands straight. The ball between his feet is protected like an egg in a basket.

A few years after Guarany was founded a young footballer with bent legs emerged in Rio. Manuel Francisco dos Santos – known by his nickname, Garrincha – subsequently became the best-known Brazilian footballer after Pelé.

In the mid-1990s, Garrincha's biographer, Ruy Castro, traced Garrincha's ancestry to the Fulniô. When journalists following up the story arrived in Aguas Belas they discovered a tribe with bent legs and a natural talent for football. More than that, the Fulniô chief, João Francisco dos Santos Filho, shares Garrincha's surname. And some Fulniô have disconcertingly familiar features – Garrincha's full lips, wide nose and jaw-heavy jowl. It was too many similarities to be a coincidence.

Jason Luna da Silva has cropped white hair and a patient, wise face. His legs stand together like an upside-down Y. He is

fifty-nine and top striker for Guarany's team of veterans. 'When we heard about Garrincha we were very satisfied,' he says

contentedly. For the Fulniô, who previously had no idea of a potential blood relation, the genetic bond was a vindication

of a vocation they already knew.

Índio only lasted a few months at Goiás. No one has word of him after that, his football career seemingly over at 23.

After a fourth consecutive football gold at the Indigenous Games 2001, the Xavante decided not to send a full strength team

to the 2002 competition, which was won by the Yawalapiti.

*cachaça: Brazilian sugar-cane spirit.