LYNN HUNT

Although debate still rages about the long-term causes of the French Revolution, almost everyone agrees that the immediate precipitating cause was the fiscal crisis of 1787–88. The threat of bankruptcy forced the crown to seek new sources of revenue, and when it could not get them from a specially convened Assembly of Notables or the Parlement of Paris, it reluctantly agreed to call the Estates General to consider new taxation. Since the Estates General had not met for 175 years, its convocation in May 1789 opened the door to a constitutional and social revolution.

Less certain are the causes of the fiscal crisis itself. Was it due to the size of the deficit, an inability to pay the interest on the debt, the failure of efforts to rationalize and equalize taxation, the limitations of the financial administration, or the reluctance of the king’s government to develop accountability to the public? All of these factors are essentially internal causes of the fiscal crisis.1 While it would be foolish to downplay their significance, especially when taken together, a global perspective casts them in a different light and offers a more convincing explanation of the origins of the French Revolution.

Two intersecting global processes were transforming government finances: France was extending its global commercial empire in order to increase its resources; and like many other great powers, it found itself increasingly dependent on an international capital market to bankroll its ambitions and even its everyday operations.2 In the 1780s France had to pay more and more to protect and administer its overseas empire, and it borrowed more and more from international creditors to do so. Foreign bankers located in Paris facilitated French access to international credit by buying French bonds for foreign investors. While the two global processes were intersecting, they effectively pulled France in different directions: on the one hand, the French government believed that pursuit of a global empire would increase its power; on the other hand, despite the country’s growing wealth, the government was losing control of its finances.

The deficit ballooned when France supported the colonies during the American War of Independence. France took the side of the colonists in 1778 in order to counter Britain’s increasing naval and commercial power. Armed intervention cost the French between 1 and 1.3 billion livres, almost all of it borrowed.3 Debt and deficits are always relative, however. The French had spent even more to fight the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) and lost, whereas they fought on the winning side in the American war and gained a measure of commercial and even naval parity in its aftermath. Comparative studies of the British and French debts have shown that the French monarchy was no worse off than its British counterpart in 1788: while the proportion of debt service to tax revenues was slightly higher in France, the ratio of debt to GNP was much lower, as was the ratio of taxes to GNP.4 Neither the size of the deficit nor the debt ratio can explain the fiscal crisis.

After the peace of 1783 victorious France found itself in a paradoxical, even contradictory, situation. With the end of war, international commerce took off, and the French gained a greater share of the expanding wealth. At the same time, the French government had to pay for both the war and the protection and administration of its growing global commerce. In the eighteenth century, the British government spent twice as much on the navy as on the army.5 The French proportions were reversed because France needed a large standing army to confront its potential challengers on the Continent. As a result, France was always playing catch-up by building new ships of the line, which invariably prompted Britain to build more of its own. This naval arms race, especially intense after 1783, put additional pressure on French finances.6 Moreover, the British and Dutch governments could borrow at a lower rate than the French: 2.5–3 percent for the Dutch, 3–3.5 percent for the British, and 4.8–6.5 percent for the French.7 Yet even though the French had to pay more to borrow, the higher yields made investment in French debt attractive to Italian, Swiss, and especially Dutch investors who could not get as good a return at home. The convergence of growing wealth, growing needs, and growing supplies of international capital made it possible for the French to borrow themselves into bankruptcy.

The Dutch and British governments could borrow at lower rates because they had more transparent forms of managing public debt. The Dutch led the way by establishing public bonds in the sixteenth century whose sale was controlled by the tax receivers themselves, but as a consequence the public debt was largely held on the provincial, not the national, level. The British ran their debt through the Bank of England, which was chartered in 1694: investors bought stock in the bank, and the bank in turn arranged loans to the government. In 1751 the government converted the stock into consols or consolidated annuities (essentially perpetual bonds). Since rates of interest were so low in Holland, Dutch investors bought into the higher yields on the British debt and from the 1760s onward also invested in Swedish, Danish, Austrian, Russian, and eventually French and United States debt as well.8

The French government had a publicly funded debt too, but it was not consolidated or guaranteed through the operation of a national bank. Because the French monarchy had a long history of partial defaults, either through suspensions of payment or absorption of higher interest annuities into new issues at lower rates (not to mention the practice in previous times of arresting creditors and confiscating their goods), the government had to pay a risk premium, an interest rate higher than the market rate. The sheer variety of debt instruments contributed to those high rates, in part because it aggravated the systemic difficulty faced by those attempting to draw up state budgets or make sense of them as investors. Among the elements of the monarchy’s public debt were rentes sur l’Hôtel de Ville de Paris (the most secure annuities because interest was paid directly out of tax receipts, but also difficult to buy and sell on the market), bonds and shares in the French East India Company, which became government obligations with liquidation of the company in 1770, the twenty different government loans offered for subscription between 1763 and 1787 (most of them either life annuities or loans with supposed set terms), and the Caisse d’Escompte (whose establishment as a discount bank in 1776 constituted in itself a government loan from investors because the government required as a condition of its establishment that 10 million l. of its initial capitalization of 15 million l. be deposited in the royal treasury).9 In addition, in order to circumvent higher rates of interest the crown regularly borrowed through the intermediaries of provincial estates, cities, companies of tax farmers, and venal officeholders.10

The crown’s budget proved so difficult to pin down that the two most prominent finance ministers of the 1780s, Jacques Necker (in office 1776–81 and 1788–89) and Charles-Alexandre de Calonne (1783–87), carried on a pamphlet war about the balance sheet, each accusing the other of deliberately distorting the truth about the deficit.11 Necker claimed he left office in 1781 with a budgetary surplus; Calonne insisted that Necker had manipulated the figures to obscure the existence of a deficit that continued to grow. Both argued for reforms; neither succeeded in achieving them. Still, they each proved all too successful at raising loans. The Swiss Protestant Necker became minister, after all, because he offered direct access to Genevan funds, being a rich foreign banker himself. It was the success of French borrowing in the 1780s that helped bring on the fatal crisis in 1788–89.

European banking had been crossing national frontiers since the fifteenth century, and it traversed them ever more frequently as international trade intensified. Global trade networks in the eighteenth century relied on bankers to provide financing of ships, insurance, and especially, bills of exchange (lettres de change), the paper equivalents of silver and gold. Bankers themselves began to cross national frontiers. French banking houses installed branches in Spain, where they had more immediate access to the Spanish gold and silver needed in the East India trade. Swiss bankers played an increasingly prominent role inside France. Of the seven original administrators of the Caisse d’Escompte, for example, five were Swiss in origin.12 In the 1780s political upheavals in Geneva, Amsterdam, and Brussels prompted a new influx of foreign financiers into Paris. They bought and sold French government bonds for foreign investors, arranged investment in private French companies and those with government privileges, and, in some cases, played the currency markets.13

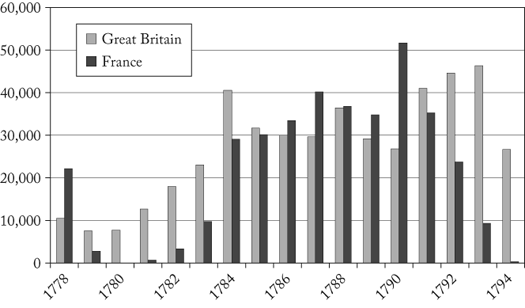

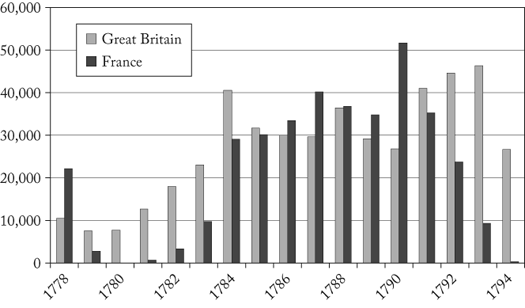

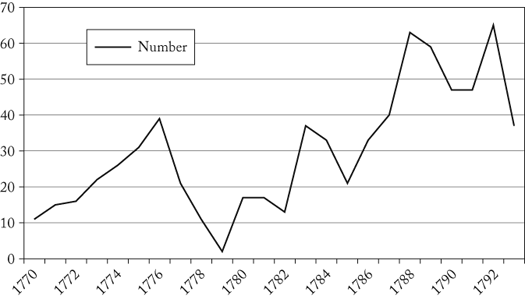

The globalization of the banking sector went hand in hand with the rising volume of international trade. Silver production in the Spanish colonies increased over the course of the eighteenth century, and when war ended in 1783, Spanish imports of silver and therefore French access to it dramatically increased.14 After 1783 the French share in both the slave trade and Indian Ocean commerce increased dramatically. During the war years from 1778 to 1783, the British controlled 52 percent of the slave trade to the Americas, while the French carried only 13 percent (see fig. 2). The French lost no time in recovering their position; in fact, the French slave trade culminated between 1787 and 1791 (just as abolitionism got going) when the French transported 40 percent of the slaves compared to 23 percent for the British.15 The East India trade reached its height at the same time (see fig. 3); the French sent the greatest number of vessels past the Cape of Good Hope between 1787 and 1792.16 The French finally surpassed both the Dutch and the British in the number of vessels traveling to the Indian Ocean.17

Figure 2. Slaves Transported, 1778–1794. Data from http://www.slavevoyages.org.

Figure 3. French Ships Going to Indian Ocean, 1770–1793. Data from Philippe Haudrère, La compagnie française des Indes au XVIIIe siècle 1719–1795 (Paris: Librairie de l’Inde, 1989), 4:1, 215.

Although companies usually specialized in one region of the global trading networks, the carrying trade in the Americas, commerce in the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic slave trade were linked together by silver, bills of exchange, and ultimately therefore bankers, who guaranteed the equivalence of silver and bills of exchange.18 Banking thus helped knit the American, Indian Ocean, and African networks into a unified French commercial empire, not to mention tying it to merchants and bankers in a host of other countries.19 The French had long had a major share in the Spanish trade with the Americas, whether through direct sales of goods, indirect participation in Spanish shipping, or credit supplied by French bankers.20 Involvement in the Spanish carrying trade with the Americas was critical because it offered access to silver. The biggest French commercial houses, such as Lecouteulx, had branches in Spain, especially in Cadiz, which was the main transhipment point for silver to the Indies. In the eighteenth century the French had twice as many international trading houses in Cadiz as any other nation, and the French often did more business than their more numerous Spanish counterparts.21 In 1782 transplanted French bankers helped form the new Banco Nacional de San Carlos (Banque de Saint Charles) in Madrid, which had a royal privilege to control the export of precious metals. Lecouteulx in Paris was charged with drumming up investors in the new bank, and by May 1785 the Lecouteulx family was the largest investor in the Spanish bank.22

The French global empire depended on Spanish silver.23 In his Manuel du commerce des Indes orientales et de la Chine of 1806, Pierre Blancard called on his thirty years of experience in the Indian Ocean trade to describe a typical cargo of a 600-ton vessel. Going to the Coromandel coast and Bengal, it would carry 795,000 francs (the franc was the equivalent of the prerevolutionary livre) worth of silver, twice the value of all the rest of its cargo, which would include, by contrast, only 40,000 francs worth of gold.24 The silver shipped to Bengal bought a variety of goods, among them the textiles and cowries (shells) used to purchase slaves in Africa.25

The cowry-silver exchange is a fascinating subject in itself. The cowries of the slave trade came from the Maldive Islands, off the coast of India; cowries grew elsewhere, but those of the Maldives were more desirable to West Africans. They were fished by women who waded into the sea and detached the shells clinging to stones underwater. The shells were buried in pits on the beach until the mollusks inside decayed and could be washed out. In Balasore, a town just south of Bengal, or Ceylon, the Maldive traders sold cowries to local merchants for rice, and Europeans in turn bought the cowries with silver. The cowry price of slaves in West Africa rose steadily during the eighteenth century, from 40,000–50,000 cowries per slave in the 1710s to 160,000–176,000 cowries in the 1770s. As a consequence, the proportion of cowries used in the purchase of slaves steadily declined from about one-half to one-third or less, yet it remained a critical element in the slave trade. Between 1700 and 1790 the Dutch imported to West Africa on average 74 metric tons per year, which translated to 60 million individual shells per year. The English average for the eighteenth century was 50 metric tons per year. A French comparison is impossible, as there is no similar statistical series available, in part because of the up-and-down fortunes of the French East India Company.26 The available evidence indicates that cowries played the same role in the French slave trade as they played in that of their competitors.27 Without Spanish silver, then, there would have been no trade with India, no cowries or Indian textiles, no slaves, no slave economy, no sugar, no coffee, and so on.

Silver did not do this all on its own. Bills of exchange stood in for silver at many stops in the trading networks.28 Ships took the cowries, textiles, and other goods bought in the East Indies back to Europe where they were sold for specie (gold and silver) or bills of exchange and used to outfit slave ships; once purchased with cowries, cloth, and other manufactured items in West Africa, the slaves were then sold either on credit or for specie in the Americas; the slavers then bought sugar, coffee, or other goods to take back to Europe. The goal at every stage was to make a profit, but to arrive at that end, silver had to be illegally or legally obtained from the Spanish and sent to India. Many scholars have described the slave trade pattern as triangular, linking Europe, Africa, and the American colonies. As this brief review suggests, it consisted, rather, of two huge loops that extended in one direction from Europe to Africa and the Americas and in the other from Europe to India and China. The circulation of goods, specie, and credit was global, not merely transatlantic.29

Although its share of this global commerce grew dramatically after 1783, France confronted international developments that potentially threatened its continuing access to silver and credit. The longest-lasting of these problems was the loss of position in India at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. Even after 1783, when the French regained some of their commercial outposts in India, French merchants increasingly relied on local British agents (and even British pilots) to carry out their local transactions. When Calonne reestablished the French East India Company in 1785, he planned to link the revived French company directly to its British counterpart. The French foreign minister Vergennes rejected this arrangement for political reasons, so the new company had to rely on financing from bankers in Paris (including the Caisse d’Escompte) and on insurance and financing of ships provided by private banks in London.30

The position in India mattered even though many more ships went to the Caribbean than to the Indian Ocean. The revived French East India Company sent 63 vessels to ports on the Indian Ocean and China in 1788, for example, while slave merchants in the French Atlantic ports were sending 783 ships to the Caribbean, 465 of them to Saint-Domingue.31 Yet India’s goods were essential for trade in Europe and Africa, and the profits in India could be high. A study of the British balance of payments at the end of the eighteenth century has shown that net transfers from India were equal or even superior to profits made from the British slave trade.32 The French balance of trade with India was much less positive, however. The British East India Company was bringing home goods valued at more than three times the amount of specie shipped to India and China between 1785 and 1791, whereas the comparable French ratio was only one to one. The French company made good profits for its directors, ranging from 5–60 percent per voyage, and offered regular dividends of 6 percent to shareholders, but it did nothing for the balance of payments of the country.33

The French also faced a realignment of trade with Spain, one that would foreshadow Spain’s break with France and alliance with Britain after 1793. In the 1780s the Spanish not only established a new national bank to control currency exports but also began to withdraw France’s long-standing status as most favored nation in trade.34 French textiles faced higher import duties, and European competitors began taking a larger share of the internal Spanish market. French bankers might still make large profits off their dealings in Spanish finances, but French manufacturers were crying foul.35 In both cases—France’s position in India and in Spanish trade—developments in the 1780s favored finance over trade and manufacturing.36 Underlying structural degradation of France’s position in international commerce thus encouraged the tendency of investors, both French and foreign, to make money off of French financial instruments rather than investing in productive enterprises.

The abundant supply of capital generated by the increase in production of silver, the international growth in trade, and the expansion of the international capital market proved too great a temptation to a French crown that continued to resist the establishment of a consolidated national debt based on accountability to the public. Necker’s Compte rendu (Account of Finances) of 1781 had broken the habitual secrecy of French government finances, but its publication provoked a furious barrage of hostile pamphlets by other high-ranking officials (including, later, Calonne).37 Necker was fired a few months later. In his account, published in the midst of the American war, he explicitly drew attention to the link between British credit and the public availability of government accounts and in particular the submission of government accounts for approval to Parliament, precisely the issues that would return with such vehemence in France in 1787–88.38 Rather than go that route, the French government seized on the new availability of capital and encouraged increasingly speculative investment in its credit instruments.39 A surplus of capital made it possible for Necker’s successors to put off the day of reckoning, but when the day came, the result was revolution, not fiscal reform.

When Calonne became finance minister a few weeks after the conclusion of the peace settlement in September 1783, conditions were ripe for a speculative frenzy. The reestablishment of the East India Company in 1785 provides a telling example. Rather than simply invest in the revived company and through it in Indian Ocean trade, individuals (and families) with capital began to speculate on the value of the company’s shares. Despite the government’s efforts to limit speculation by requiring brokers to declare all shares that had been bought on time contracts (some bet on a decline, others on a rise in share prices), opportunists began snapping up shares not only in the East India Company but also in the Caisse d’Escompte, the new water company, and three new insurance companies.40 Share values rose precipitously in late 1785 and 1786. In an attempt to stave off a collapse that was widely feared at the end of 1786, Calonne funneled 11.5 million l. in treasury funds to a syndicate instructed to buy up East India Company and water company shares in order to shore up the prices. One of Calonne’s chosen agents took the occasion to corner the market (get control of all the shares in order to drive up prices) in league with a clergyman from a noble family and major shareholder in the East India Company, Marc-René Sahuguet d’Espagnac. When the market manipulation was revealed in a pamphlet published by Mirabeau in March 1787 (Dénonciation de l’agiotage [Denunciation of Speculation]), Calonne ended up losing nearly 25 million l. for the government.41 Just when he was trying to convince the Assembly of Notables to reform government finances, Calonne had to order liquidation of the corner and absorb the losses of speculators. Two leading Parisian bankers, the Swiss-born Rodolphe-Emmanuel Haller (son of the famous Swiss writer Albrecht von Haller) and Barthelemy Lecoulteulx de la Noraye (also involved with the Banco de San Carlos), were charged with selling the cornered shares, which promptly declined in value. Calonne was fired in April because he had lost his credibility.

The speculative boom had more than one source, but contributing to it was the influx of foreign financiers who were coming to Paris in response to political upheavals in surrounding countries. Étienne Clavière came to Paris in 1784 after finding himself on the losing side of the Genevan revolution of 1782. The Dutch bankers Balthazar-Élie Abbema and Jean-Conrad de Kock fled to Paris to escape the repression of the Dutch patriots in 1787. Others, like the Belgian comte de Seneffe, one of those originally working for Calonne to buy up shares, or the British banker Walter Boyd, a financial agent for the French East India Company, came because a “get rich quick” atmosphere prevailed after Calonne came to power in November 1783.42

Clavière never established a big bank like Haller, Lecouteulx, Seneffe, or Boyd, yet because he was arrested and his papers were confiscated during the Terror, his activities provide the most insight into the financial machinations occurring at this critical time. Among his papers was a register with entries dating from April 1786 until July 1789.43 For April 1786, when he started the register, he listed holdings of 4,668,117 l., which included investments of 104,750 l. in shares of the Caisse d’Escompte (with which he did regular business), 1,269,582 l. in shares of the revived East India Company, and 16,000 l. in the water company. He also held 135,000 l. in English consols and 2,296,160 l. in various French government bonds and annuities. Clavière’s debts outstripped his assets, however. He listed outstanding obligations of 6,549,284 l. Clavière was a baissier, a short seller. He owed 393,090 l. on East India Company shares, 318,996 l. on water company shares, 108,350 l. on shares in the Caisse d’Escompte, and 380,911 l. on shares in the Banco Nacional de San Carlos, which had also become the subject of French speculation.44 Clavière undertook more than one kind of maneuver. His multimillion l. gamble on shares included speculation on the share price (borrowing shares, selling them at a high price, then repurchasing them later at a much lower value and returning them to the borrower and pocketing the difference) or betting, in the case of the Caisse d’Escompte, on the dividend that would be paid, hoping again that the rate would fall over time.45

Clavière did not trust the market to achieve his aims, so he fed information and probably even pages of prose to Mirabeau, who wrote pamphlets against speculation in shares of the Banco Nacional and the water company, and later to Brissot, who published pamphlets against the water company and a proposed fire insurance company.46 Clavière hoped to benefit from a resulting decline in share values, and he also wanted to set up his own water and insurance companies. He played a leading role in the formation of two new insurance companies, one against fire (1786) and one for life insurance (1787). Having lived in Great Britain after his exile from Geneva, he had learned about actuarial tables and saw an occasion to profit from his new knowledge. He and his allies had the right contacts at court to get the projects approved, but the schemes hardly got off the ground before 1789 (needless to say, his mouthpieces did not attack these two companies in print). For all his efforts, Clavière could not always correctly time the market for company shares, and in the end he preferred investing in French government debt, for “the high rates of interest make up for the risk.”47 Clavière wrote those words to one of his biggest creditors, Pieter Stadnitski, an Amsterdam banker, who had loaned him 521,429 l. (Stadnitski was one of the chief funders of the debt of the new United States).48

Most striking about Clavière is the suddenness with which he entered the speculative scene. His livre de caisse (account book) runs from January 1781 until October 1787 with some unfortunate gaps. From January 1781 until March 1784, the sums involved are not immense, ranging from a starting credit of 15,443 l. in mid-January 1781 to a reconciliation of accounts at the end of 1781 at 53,297 l (not exactly a trivial increase, however).49 In December 1782 he reconciles his accounts at only 6,130 l. (folio 24), and in March 1784 at 3,150 l. (folio 34). Suddenly, eighteen months later, in August 1785, he opens with 136,945 l., most of it commercial paper from various bankers (folio 35).50 The numbers rise vertiginously thereafter: by mid-November 1785 the amount is 198,682 l. (folio 38), and three weeks later 279,116 l. (folio 40), all of which he has paid out. Having once again restarted his accounts, by mid-January 1786 he has 437,581 l. (folio 42), and by mid-March 1,017,253 l. (folio 44, all paid out). He restarts his account again in April 1786, and by the end of September he has 2,516,836 l. (folio 55), by the end of November 4,963,840 l. (folio 57), by early January 1787 7,185,970 l. (folio 59), and by the beginning of April 1787 10,044,991 l. (folio 62).51 At the end of June 1787 he stops putting in figures, and the account ends altogether in October. Clavière pays out even more than he brings in, but under paying out he includes paying for shares in various companies, which constitute his investments. Although it is impossible to determine the precise size of Clavière’s own fortune from this account book, it is clear that in a very short period of time and in a newly speculative setting, he parlayed substantial loans from bankers into major holdings of his own. Clavière made his fortune entirely from speculative investments.

Mirabeau, Brissot, and Clavière all gained reputations as righteous denouncers of market speculation, whereas Calonne lost his job, and the rates on government loans increased to ruinous levels (7–10 percent).52 Yet insiders knew that investors were mounting pamphlet wars for something other than high-minded ends. When Mirabeau’s Dénonciation de l’agiotage appeared in March 1787, just as the Assembly of Notables was beginning its deliberations, a widely read underground newsletter seized on its significance: “What renders his zeal even more suspect is the adroitness with which he only unleashes his lightning bolts of eloquence against those who are playing for a rise in the market…. Such a pronounced partiality has not failed to make people suspect those betting on decline, Clavière, Panchaud and others, of having once again solicited this latest production at the same price for which they obtained previous ones.”53 The editors of the newsletter nonetheless worried that the damage was done; Mirabeau’s vitriolic denunciation of Calonne and his prediction that the finances of the country would be ruined and bankruptcy was therefore inevitable had provoked public indignation and undermined the financial credibility of the government. In the end, then, the combination of speculative excesses and the linking of them to the government through pamphlet wars played a greater role than the deficit itself in bringing down the government. Calonne’s successors could not stanch the blood, and the door opened to revolution and the promise of massive fiscal reorganization.

The machinations of bankers, foreign and French, and the pamphlet wars that sapped the government’s credibility were not the only factors bringing on the upheaval of 1789. Massive unemployment in the textile sector, which followed the free trade treaty signed with Great Britain in 1786 and poor harvests in 1788 and 1789, inflamed both urban workers and peasants who could not afford to feed themselves. When the constitutional crisis began, the popular classes were ready to make their voices heard, whether in riots or meetings held to assemble their grievances in preparation for the Estates General. The intervention of the popular classes radicalized the revolution that unfolded, but there would have been no revolution if the nation’s creditors, both foreign and domestic, had not lost confidence in the government.

After the Revolution began, the issues of the government’s debt and the international bankers’ role in it did not disappear. In 1789 Clavière argued strongly against the repudiation of the crown’s debt, and in 1792 he became finance minister.54 Arrested as one of the Girondins on 2 June 1793, he committed suicide before he could be tried.55 By the end of 1793, many foreign bankers had fled, been arrested, or executed. Global finances would be as crucial to the unfolding of the French Revolution as they had been in causing it.

Confidence is not an entirely rational calculation, as any investor in stock markets knows all too well. Investors in France in the 1780s had many reasons to feel confident. France’s global trade was soaring, and the supply of silver as well as credit was increasing. True, France had had to join a war against Britain in order to protect its global commerce and imperial ambitions, and that war was expensive, but no more so than it was for Britain. Peace opened a period of prosperity and profits, but exaggerated expectations among those with access to capital led to a crisis that could no longer be solved by the usual methods. Central to that crisis in France were the operations of an ever more-globalized commercial empire and an increasingly international market for capital.