There are hundreds of Canadian communities that have given more thought to hiring their rink manager than they have to electing their Member of Parliament.

—Preston Manning, The New Canada (1992)

The habit of treating Alberta as an exploitable and resource-rich hinterland goes back three hundred years. And why should a self-centred Canada change its attitude? Canada as a country is an act of imagination so unlikely that it is hard to believe its actual success. . . .

—Aritha van Herk, Mavericks: An Incorrigible History of Alberta (2001)

Preston Manning is one of the most consequential and intellectually creative political figures of the past twenty-five years. Which other politician who never got to be prime minister has had so much impact on the national political conversation?

—Jeffrey Simpson (2015)

At the start of the twentieth century, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier predicted that the century would “belong to Canada,” and as the country matured, there were times when such confidence seemed justified. The anthem, flag, and literary culture had boosted a quiet patriotism. Youngsters who explored the world sewed maple leaf badges on their backpacks. By the end of the century the population had soared to over thirty million (five times the number of people in Laurier’s Canada) as immigrants and refugees from South America, Africa, and Asia continued to arrive.

However, the last years of the twentieth century saw growing tensions that challenged the Canadian talent for compromise and “muddling through.” How could one country accommodate the rural-urban split, the divide between resource-based western economies and others, Quebec’s secessionist movement, and the Indigenous peoples’ campaign for self-government and Indigenous rights? Was this country going to dissolve, and all its promise go to waste?

Populist movements in different regions have challenged the status quo ever since George-Étienne Cartier introduced federalism as the solution to regional tensions. However, in the late 1980s the Macdonald-Cartier political bargain that had kept the different provinces tenuously glued together was fragmenting. Not only had the Meech Lake Accord failed, bringing Quebec nationalists into the streets and shattering the Progressive Conservative Party, but the brushfire of a new populist movement had ignited in the West. It was carefully nurtured by Preston Manning, a soft-spoken preacher and management consultant who was Alberta born and bred.

Populism has a long and complicated history in Canada. It has flourished when large numbers of citizens feel that the game is rigged against them and they are being ignored. Unlike American populist movements, Canadian populism rarely deteriorates into racist demagoguery; in common with American populism, it frequently involves hostility to an economic order dominated by “money power.” In Canada, “money power” always means the moguls of central Canada.

Some populist protests simply fizzle out, when the naïveté of their policies meets the reality of governing such a sprawling country. But others have had a profound impact on the national agenda. In the early twentieth century, farmers’ parties in Ontario, Alberta, and Saskatchewan pulled political debate leftward with their anti-business rhetoric and their demands for participatory democracy and farmers’ collectives. This was the world from which Tommy Douglas drew his political inspiration. A similar tug to the left came from two initiatives in the Maritimes in the 1920s: the Maritime Rights Movement, which demanded better economic treatment by Ottawa, and the Antigonish Movement, led by Father Moses Coady, which concentrated on strengthening the local economy through co-operative action.

Other populist movements yanked debate to the right. The Social Credit League of Alberta, born in the bitter Depression years, promoted conservative social values as well as raging against big business and the banks. Similar right-wing populist movements emerged in Quebec too, from the 1940s: first Maurice Duplessis’s provincial Union Nationale party, then the federal Créditiste party, led by Réal Caouette.

Populist leaders like to claim they speak for “regular folk”—“the little guy” for Tommy Douglas; “ordinary Canadians” for Preston Manning. The authority of populist leaders comes from a direct bond with their supporters. They promise that government will be closer to the people, and that “regular folk” far from centres of power will get a break.

Leaders of surging populist movements have become provincial premiers—William Aberhart in Alberta, Maurice Duplessis in Quebec, Joey Smallwood in Newfoundland—but none has ever become prime minister. However, successful populists can redirect the way we think about our country, shake up the other political parties, and jump-start new initiatives, as Tommy Douglas did by championing a national health insurance program. Preston Manning founded a populist party dedicated to asserting western demands and pruning Ottawa’s powers. Just as Elijah Harper forced Canadians to pay more attention to the way Indigenous peoples were treated, so Manning would try to rebalance the Canadian federation and give the West more power.

“Never say ‘Whoa’ in a mudhole!”

My neighbour roars with laughter as he sees the incomprehension on my face. I have no idea what this western expression means. It is March 2015, and we are at a black-tie dinner at the Ranchmen’s Club, a posh private establishment in Calgary that ripples with financial muscle. Founded in 1891, the Ranchmen’s is similar to such clubs in wealthy cities across North America. Tonight’s dinner guests are as urban, educated, and affluent as their counterparts in the Toronto Club or the Vancouver Club. But wait . . . How about the stuffed buffalo heads in the foyer, or the outbreak of cowboy boots among the patent leather pumps? Yes, this is Alberta—our petro-province, quietly regarded by some Canadians elsewhere as overstuffed with XXL-sized Stetsons and right-wing swagger. The Ranchmen’s Club was founded before this city had sidewalks.

The overflow crowd at this exclusive event is enjoying itself: there are frequent toasts, punctuated with hoots of laughter. You would hardly know that Alberta’s economy is tanking, because of a calamitous global drop in oil prices, until the premier of the day rises to speak. Jim Prentice has entered provincial politics only six months ago, after a successful career as a lawyer, federal politician, and banker. Personable and self-deprecating, he has just become sixteenth premier of the province as it enters its eightieth year of deep-dish conservatism, first with Social Credit governments and then with Progressive Conservative governments. This is a province that embraces one-party rule, free enterprise, low taxes, and a deep distrust of central Canada.

Prentice is speaking tonight to his kind of people: bankers, oilmen, businessmen, entrepreneurs. As we tuck into grilled Alberta beef with plum and fig polenta, my dinner companion (a former chair of the Calgary Stampede) gives me a quick rundown on other guests at our table. Most of them, he points out with pride, started with “zip” and have made it big. Then Premier Prentice is on his feet, giving his audience the bad news: looming deficits and job cuts. I look around, noticing a mix of blank stares and sage nods.

A few weeks later, with polls running in his favour, Prentice calls a provincial election. But then the unthinkable happens: a massive shift of opinion across the province. Two months after the Ranchmen’s dinner, the Alberta electorate turfs Prentice and the Conservatives and triggers shock waves across Canada. The left-wing New Democrats sweep aside nearly eight decades of right-wing supremacy. Our petro-province will be under socialist rule.

“Never say ‘Whoa’ in a mudhole.” What my neighbour had meant was that Albertans never wallow in a slough of despond: they dig their spurs into their horses’ flanks and keep moving. Alberta’s Conservative Party, as Jim Prentice had discovered to his cost, had become intellectually and politically bankrupt—a mudhole. The electorate had decided en masse to gallop off in another direction, whatever the risk.

A couple of weeks after the provincial election, Preston Manning, these days an elder statesman for many conservatives, gave me his opinion of the result. “I wasn’t really surprised,” he responded, in his distinctive nasal drawl. “The NDP win fits into the Alberta pattern of one-party government. Change comes when Alberta’s voters turn against a tired old bunch and toward a fresh new bunch.” Provincial NDP leader Rachel Notley had won the election not because of her socialist ideology, he said, but because she connected with the grassroots.

Manning knows all about triggering political change by connecting with the grassroots. For decades, during political campaigns and conventions, he stood on platforms in church basements and convention halls, a skinny, slope-shouldered man with a bemused expression, waving an index finger in the air and appealing to “ordinary Canadians.” He reckons that a distinguishing characteristic of Alberta’s political culture is its willingness to accept a “new party” as an instrument of change.

From the mid-1980s to the political upset of 2015, thanks to population changes and the fossil fuel economy, power in this country shifted westward. The populations of Alberta and British Columbia grew faster than those of most other provinces; major oil companies relocated their Canadian head offices from Toronto or Montreal to Calgary. In the process, some of the old liberal (large-L and small-L) assumptions about this country were shaken. Granted, Canadians continue to regard our health care system, the Maple Leaf flag, and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms—all achievements of Liberal governments during the second half of the twentieth century—as intrinsic to our national identity. But Canadian opinion swung toward greater acceptance of free markets and more skepticism about government interventionism.

This shift reflected larger global swings, but Manning certainly pushed Canadians to move in this direction. Since Confederation, federal politics had been dominated by our two “big-tent” parties, which were often largely indistinguishable on issues such as state intervention or law and order. They took turns governing, depending on leadership and how well they brokered regional and religious cleavages. The parties were most successful when they hewed to the centre of the political spectrum and paid closest attention to the two largest provinces in the centre of the country, Ontario and Quebec.

This was certainly true of Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives when, in 1987, Preston Manning planted the seeds of a new political movement in western Canada that would grow into a national and far more conservative organization, the Reform Party. The political analyst Robin Sears, from Earnscliffe Consulting, suggests that Manning was the Canadian version of an American “states’ rights” politician. “He accepts Ottawa’s role, but he’s anti-centrist, perhaps because he grew up as an outsider. Nobody ever loses that sense of being excluded and disrespected.”

Preston Manning would lose control of the changes he had triggered and would limp away from the reborn ideological Conservative Party that emerged from the Reform Party chrysalis. But his movement and vision for Canada coloured Canadian attitudes to government, gave the Liberal Party a free ride for two elections, and eventually led to the emergence of a new Conservative Party with a strong base in the West.

So although Manning failed in his own political ambition, his role has been critical. Where did this vision come from? It was deeply embedded in the DNA of both his province and Manning himself.

Preston Manning is one of forty-six “mavericks” featured in a permanent exhibit, The Story of Maverick Alberta, in the Glenbow Museum, a Calgary museum that tells the story of southern Alberta and the West. What is a maverick? The story goes that a Texas rancher named Samuel A. Maverick did not wish to brand his cattle, so unbranded calves came to be called mavericks. According to the Calgary writer Aritha van Herk, author of the book Mavericks, on which the exhibit is based, “Albertans are mavericks, people who step out of bounds, refuse to do as we are told, take risks, and then laugh when we fall down and hit the ground. . . . Our history is different, our politics are different, our ways of thinking are different.”1

Each of Canada’s ten provinces and three territories is unique. (Don’t ever confuse a Nova Scotian with a Prince Edward Islander, or think a Cape Breton accent is from Newfoundland.) When I first arrived in Ontario all those years ago, I noticed a certain curled-lip discomfort among my fellow central Canadians about Albertans. Mordecai Richler famously dismissed Edmonton as “the boiler room of Canada” and said that Calgary looked as though it had been uncrated yesterday. When I asked what it was like, I was frequently told, “Think Texas” (this was not a compliment), and there is indeed an American tinge to Alberta attitudes.

Yet there is an optimism about Albertans—a belief that you can reinvent yourself—that is a refreshing contrast to the pursed-lip caution that historically has characterized Canadians elsewhere. The province’s residents take pride in their prickliness: to quote van Herk again, “Aggravating, Awful, Awkward, Awesome Alberta.”2 Land of the Rockies and the rodeo, booms and busts, Alberta boasts the tallest mountains, the oldest rocks, the fastest-growing population. It has become the country’s wealthiest province, thanks to winning the geological lottery and discovering that it sits on top of vast oil fields. Yet in the first half of the twentieth century it was so poor that it twice flirted with bankruptcy.

Alberta’s catalogue of grudges against central Canada is as colourful as it is long, and Preston Manning grew up steeped in them. He explored a century of fights in a 2005 academic paper entitled “Federal-Provincial Tensions and the Evolution of a Province.”3 In Manning’s telling, relations with Ottawa went off the rails even before Alberta was born. Frederick Haultain, who between 1897 and 1905 served as premier of the North-West Territories (including present-day Alberta, Saskatchewan, and most of Manitoba), had lobbied for just one new province, to be named Buffalo. A united West, with a nice beefy name, would have more bargaining power against the centre. But the Liberal government in Ottawa opted to divide and rule. In 1905 it created two provinces and named the one that abutted the Rockies Alberta, after one of Queen Victoria’s daughters, Princess Louise Albert. Moreover, it wasn’t until 1930, after a fight with the federal government, that Alberta (along with Saskatchewan) won control of its natural resources—resources that would come to dominate Alberta’s economy.

By the time Preston Manning was born in Edmonton in 1942, Albertans—still a largely rural people, toiling behind plows and on harvesters—had already demonstrated their predilection for maverick politicians and one-party landslides. First, the populist United Farmers of Alberta toppled the sitting Liberals in 1921 and endorsed policies like a provincial hail insurance scheme, a farm credit program, and the Alberta Co-operative Elevator Company. Next, in 1935, the UFA was toppled by another populist newcomer, the Social Credit Party, founded by the charismatic preacher “Bible Bill” Aberhart.

Today Alberta’s Social Credit Party is remembered as the “funny money” party. It claimed it would loosen the grip of eastern banks and institutions on the money supply by promising to pay $25 to every adult Albertan in the form of a “prosperity certificate.” A $25 dividend sounded pretty good to farmers facing bankruptcy. North America was in the middle of its worst depression ever, leading to a horrendous collapse in average farm income from $1,975 in 1927 to $54 in 1933. Alberta’s debt-plagued farmers were burning wheat they couldn’t sell and killing cattle while people around them were starving.

But the $25 prosperity certificates were of less value than Canadian Tire money: they turned out to be paper currency substitutes churned out by an Alberta printing press. And Aberhart’s solutions defied the British North America Act’s stipulation that Ottawa controlled the banking system: only the federal government could “prime the pump.” Bible Bill never explained how his government would fund the $25 dividends. Instead, he ranted on CFCN Radio and in packed Calgary theatres against the “fifty big shots” and the “high mucky-mucks” in central Canada who kept Albertans in poverty. His provincial banking system was shot down by Ottawa, which reluctantly bailed the province out.

There is a lot not to like about Bible Bill. He was dictatorial, contemptuous of many aspects of democracy including a free press, and—like his economic mentor, the British engineer Major Clifford H. Douglas—anti-Semitic. Nevertheless, Social Credit’s educational policies and labour legislation were among the most advanced in the country, and the Aberhart government created the Métis Settlements in northern Alberta—the first official recognition of the Métis as a group with Indigenous rights.

William Aberhart served as premier of Alberta from 1935 to 1943 and casts a long shadow over Alberta’s history. In his memoir Think Big: My Adventures in Life and Democracy, Preston Manning describes him as “courageous, bombastic, and stubborn. . . . He was either loved or hated.” Manning argues that the founder of Alberta’s Social Credit party gave his voters hope in desperate times. “While a historical canard has taken root that he was a discredited and even despicable failure, in fact, Aberhart gave new life and expression to an axiom of Western politics that inspires many Westerners to this very day: If you find the economic or political status quo unacceptable, Do Something!”4

Which, if you think about it, is another way of saying, “Never say ‘Whoa’ in a mudhole.”

One of the smartest things that Aberhart did was to recruit Ernest Manning, Preston’s father, to be his aide, chauffeur, and co-worker. While still in his teens, Ernest Manning was drawn to Bible Bill’s Christian evangelism; the Saskatchewan farmer’s son built his own crystal radio set so that each Sunday he could listen to the old man’s radio show, Back to the Bible Hour, on Calgary’s CFCN radio station. In his early twenties Ernest Manning attended Aberhart’s Calgary Prophetic Bible Institute and became its first graduate. The preacher started to treat his serious young acolyte as an adoptive son. Manning was soon spreading the fundamentalist gospel himself, while courting another of Bible Bill’s disciples—Muriel Preston, the quick-witted, sharp-tongued pianist at the institute.

Aberhart dazzled the two prairie youngsters, both from hardscrabble backgrounds, with his vision of a better tomorrow. “My parents’ lives and homes were infused with a panoramic sense of history and big ideas of economic and social reform, democratic processes, and populist politics,” Preston writes in his book. Manning Sr.’s evangelism morphed into an anti-establishment political crusade alongside that of his mentor. In 1935, when Albertans voted en masse for Aberhart’s folksy charms, twenty-six-year-old Ernest Manning was elected in a Calgary riding and joined the cabinet as provincial secretary and minister of trade and industry.

Ernest Manning and Muriel Preston married in 1936. Preston, their second son, was born in 1942. A year later, Premier William Aberhart died and Manning succeeded him as party leader and premier of the province. He would be premier for the next quarter century, yet politics were rarely allowed to intrude on family. “My father never invited politicians into our home, and the media respected the separation of public and private life.”5

Preston Manning’s brief account of his childhood in his memoir is suffused with the impact of the Great Depression on the lives of his parents and thousands of homesteaders. Manning himself is not a particularly introspective man, and he resorts to anecdotes only to illustrate political or moral points. His mother’s stories of families where children were fed on gopher stew and clad in garments sewn from flour sacks are quoted as parables to suggest our moral obligation as individuals to care for the less fortunate.6 The Alberta writer W. O. Mitchell depicted the small-town scrimping, saving, and misery of the 1930s prairies much more vividly in the classic Canadian novel Who Has Seen the Wind. “Houses needed paint; cars on Main Street on Saturday night were older models; plate glass windows were empty where businesses had left. . . . [Hobos] left their penciled marks on doors of generous people: ‘Champ 32’, ‘CPR 10’, ‘CNR Jos’, ‘21-Circle.’ ”7

Mitchell’s novel and Preston Manning’s memories are tinged with a romantic view of prairie resilience to which many Albertans still respond; “old-timers” are featured at every Calgary Stampede. Yet by the time that Manning was in school and Mitchell’s novel was acclaimed, Alberta was on fast-forward. The Second World War boosted the provincial economy; the discovery of oil in Leduc in 1947 changed everything. Cattle now grazed between oil rigs. By 1951 more Albertans lived in cities than on farms, and the province’s population was close to one million, surpassing for the first time those of Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Premier Ernest Manning, child of the impoverished West, lived every politician’s dream; for most of the postwar period, the good times rolled. Aberhart’s funny money theories were left in the dust as oil money transformed Alberta’s standard of living. Big Chevrolets purred along newly blacktopped roads, and the Ranchmen’s served sixteen-ounce steaks.

The Manning government kept its distance from central Canada. “Rightly or wrongly,” Preston Manning observes, “many Albertans emerged from the Depression and War years with the conviction that when they and their province [were] in deep trouble they were largely on their own, but when the nation was in trouble, they were expected to come to its aid.”8 And even as Alberta’s spending on education, health care, and roads became the highest in the country,9 Premier Manning stuck to the rhetoric of frugality and forbearance. He reminded voters that “our material assets must be augmented by the greatest possible development of all spiritual and moral resources.”10 Alberta’s minimum wage remained twenty-five cents an hour below the recommendations of the Canada Labour Code. Liberal initiatives like medicare and social housing were furiously resisted as unwarranted intrusions into provincial jurisdiction.

One day in 1963 Preston climbed the stairs of the legislative building to visit his father and discovered the premier frowning over a telegram from Prime Minister Lester Pearson. Troubled by the stirrings of Quebec’s independence movement, Pearson was proposing a royal commission that would, he hoped, cement national unity. It would be called the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, and it defined Canada as “an equal partnership between two founding races,” the French and the English, “taking into account the contributions made by other ethnic groups.”

Pearson’s telegram outraged Premier Manning. He regarded this step as “worse than misguided,” according to his son. German, Scandinavian, and central European immigrants had helped settle the prairies, and Chinese and Sikh Canadians clustered in the cities. In the Manning view, Pearson’s attempt to impose “a central Canadian definition of Canada as a whole” was downgrading both Alberta and its people.11 Why, he asked, should those French-speaking Quebecers take precedence over Edmonton’s large Ukrainian population?

As the premier’s son, Preston Manning himself never knew hardship; he grew up in a comfortable middle-class home in Edmonton, with weekends on the family farm where a foreman looked after seventy head of dairy cows. While in school, he often went to the legislature after class and sat outside his father’s office, doing his homework as politicians and petitioners came and went. At home he watched his father, “my mentor and my hero,” sit at the kitchen table, using a mechanical adding machine to prepare budget speeches. At his father’s suggestion, his rock-ribbed reading choices included The Revised Statutes of Alberta, Will and Ariel Durant’s multi-volume Story of Civilization, and Winston Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking Peoples. Whether he realized it or not, Preston Manning was preparing himself to go into the family business.

For six days a week, Ernest Manning focused on politics; on the seventh, he spread God’s word. Preston Manning describes his father as “the best preacher I had ever heard.” The Mannings had taken over Aberhart’s radio program and retitled it Canada’s National Back to the Bible Hour (Muriel was music director), and Preston took notes of all his father’s sermons. Alongside his parents, he attended the Fundamental Baptist Church—like the Social Credit Party, an independent, self-organizing unit rather than an established institution with a long tradition of rules and rituals. His commitment to free enterprise, self-reliance, and Christian values was absolute. It was a very Alberta approach, highlighted by an expression popular during the province’s Golden Jubilee celebrations in 1955, when Preston was thirteen: “Places don’t grow, men build ’em.”12

By the time Ernest Manning announced his departure from provincial politics in 1968, his son had graduated in economics from the University of Alberta. Lanky and bespectacled, the boy who had memorized the periodic table of the elements in school was the very definition of a geek. He followed closely in his father’s footsteps. He often spoke on the premier’s radio broadcasts; he had run as a Social Credit candidate in the federal election (with no chance of winning); he wrote large chunks of Ernest Manning’s book Political Realignment: A Challenge to Thoughtful Canadians, published in 1967, the year of Expo. This slim volume urged a shakeup of the traditional political establishment because “the distinctions between the Liberals and Progressive Conservatives are rapidly being reduced to the superficial distinctions of party image, party labels and party personalities.” Ideology should replace the pragmatism that had helped Canada muddle through the previous century. Political Realignment foreshadowed Preston Manning’s plans to re-engineer federal politics in Canada.

Several party insiders urged Ernest Manning to anoint his son as his successor, but the premier refused. Social Credit supremacy was about to be challenged by a young Harvard-educated Progressive Conservative lawyer, Peter Lougheed. (“A Madison Avenue glamour boy with the charm of an Avon lady,” sniffed Manning Sr.13) Within three years, Lougheed’s provincial Conservatives had swept aside Social Credit in the kind of landslide election victory in which Alberta specializes. “Another political tornado had dusted through the province,” as Aritha van Herk puts it. “Alberta changed again, with Lougheed articulating a sophisticated and updated version of Alberta’s pride and independence.”14 Social Credit was toast: both Ernest Manning and his son now seemed hopelessly fusty compared with the cuff-shooting Lougheed crowd.

Preston Manning would spend the next twenty years as a management consultant, in partnership with his father in Manning Consultants Limited. While his father joined eastern corporate boards and was appointed to the Senate, Preston sat in corner offices, explaining to executives how their organizations could be slotted into matrixes, charts, and models. His clients ranged from oil companies and public utilities to community development organizations; his particular expertise was retooling organizations from the bottom up. He also married the forthright and lively Sandra Beavis, a graduate of Alberta’s Prairie Bible College and a student nurse who attended the same church as the Mannings. Preston Manning speaks frequently about his wife with unequivocal respect for her personally, and also for the sacrifices required of women who marry politicians. “Measured in terms of my future well-being, my family, and my business and political career, asking Sandra to marry me was the smartest decision I ever made.”15 The Mannings would have five children. But as Calgary sprouted glass towers and new subdivisions ate up the surrounding fields, Preston never stopped brooding about politics.

However, with his Social Credit roots, the younger Manning remained uncomfortable with the traditional political establishment. Climbing rungs was not his style. His fellow Albertan Joe Clark, who had joined the federal Progressive Conservative Party when he was sixteen years old, urged Manning to follow his example. “He kept saying to me that I should get in and change the party from within. But I could see that wouldn’t work. As long as a party is successful, the old guard will block change.”16 He was confident another “prairie fire” would start smouldering, allowing him to challenge the establishment from outside the tent. It was all a question of timing: he could not “Do Something,” in the Aberhart mode, until there was grassroots momentum. “Rather than getting in on the tail end of the populist movements produced on the Canadian prairies during the Depression, I would wait for the next one.”17 But he was already planning a western-based populist movement, committed to a small government agenda, that would evolve into a national party. He knew what he wanted to sell; he just needed an audience ready to buy. “You can’t manufacture a third party: only when people are angry can you try and harness the energy.”18

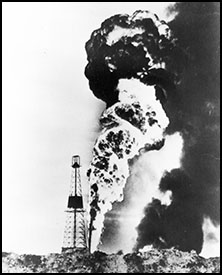

In the next few years, anger began to simmer. This was the era of the energy wars between Ottawa and Alberta. After the OPEC cartel raised world oil prices in 1973, Ottawa watched Alberta’s oil revenues climb. When the second oil shock hit in 1979–80, tripling oil prices, Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau decided to introduce a tax on oil exports. This move would effectively lower prices for domestic consumers and raise revenues for Ottawa. It also created an incentive to shift to oil exploration in federally controlled regions offshore and in the North. The feds argued that this interventionist National Energy Program was in the national interest because it would allow Canada to have more balanced development and an equitable sharing of the benefits of oil.

Such an argument might have made sense even to some Albertans in the early twentieth century, when “nation building” for a precarious Confederation had included the idea of interregional subsidies. But now Albertans reacted with fury: the NEP forced them to sell their oil below world prices. It excited the most primal of their anxieties—the fear they would lose control to outside interests, and that those interests would rob them of their patrimony.

This was Alberta’s resource, argued Premier Lougheed, for the province to use to strengthen and diversify its own economy. Many, like Manning, saw the NEP as an even more nefarious scheme: “a massive raid by a spendthrift federal government on the resource wealth of western Canada.” Some Albertans plastered their cars with bumper stickers that read, “Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark.” Pierre Trudeau became a pariah in Alberta, and Lougheed, the “blue-eyed Arab of Saudi Alberta,” beat back Ottawa’s attempt to control a provincial resource. But the number of oil rigs operating in Alberta dropped from 400 to 130.19

The high price forecasts of the NEP were soon discredited as world oil prices tumbled and a recession further dented Alberta’s economy. As he chatted to his corporate clients, Preston Manning heard their exasperation with Ottawa’s policies, which, they argued, were bleeding money out of the West. All Ottawa cared about, they grumbled, was Quebec. With the election of a separatist government in Quebec in 1976, the burning issue in Ottawa was national unity. A proliferation of task forces and cabinet committees grappled with scenarios and sweeteners as a Quebec referendum loomed. The two-decade-long constitutional battles had begun, featuring the 1980 referendum, the Constitution Act, and the Charter of Rights, plus two failed attempts (the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords) to get Quebec to sign the Constitution Act. It was a volatile and uneasy period in national politics: Brian Mulroney would replace Pierre Trudeau as prime minister in 1984; Elijah Harper, speaking for Indigenous peoples, would scupper the Meech Lake Accord in 1990; the Charlottetown Accord would be defeated in a hard-fought national referendum in 1992.

Throughout it all, Albertans felt ignored.

There were now crabby little eruptions of western separatism, including the formation of the Western Canada Concept party. An Alberta farmer, Bert Brown, plowed the slogan “Triple E Senate or Else” into his neighbour’s three-kilometre-long wheat field outside Calgary to demonstrate support for an “elected, equal, effective” upper chamber.

However, in Manning’s view, Alberta’s separatist initiatives weren’t really serious. They were simply tactics to draw attention to western grievances. The prairie fire for which he was watching was not yet ablaze. He continued to wait.

Nobody was happier than the denizens of the Alberta oil patch when the Progressive Conservative leader Brian Mulroney became prime minister in 1984—even though he came from Quebec. The federal Progressive Conservatives won every single seat in Alberta, while the Liberals were almost completely shut out of the West. But enthusiasm soon soured. “The West expected spending to be controlled, the deficit to be dramatically reduced, [plus] tax relief and a new sensitivity to Western aspirations and concerns,” explains Manning. Instead, Mulroney’s government showed no interest in cutting taxes and was as focused on Quebec as its Liberal predecessor. Moreover, western conservative support for old-fashioned “family values” (which included hostility to abortion, homosexuality, and premarital sex) was shunned by Ottawa’s Conservative power brokers. Manning recalls, “I heard the rumblings of disappointment in the boardrooms and on the streets as I made my consulting rounds. . . . The grass was dry—very dry. One spark, and who knew what might happen?”20

In Preston Manning’s version of history, that spark was a federal decision—“in the national interest”—that a Montreal company rather than a Winnipeg corporation should get the maintenance contract for Canada’s CF-18 jet fighters, even though the Winnipeg firm’s bid was lower. The CF-18 decision convinced many westerners that a change of government in Ottawa hadn’t changed anything. Preston Manning reckoned, “All the conditions for a full-blown prairie fire were now present. . . . It was time to act!”

Never say “Whoa” in a mudhole. Ernest Manning’s son spurred his horse into a gallop.

Preston Manning was ready to ride the wave of public discontent, and he had plenty of backing within Alberta—not least, Ted Byfield’s newsmagazine Alberta Report, which presented a slick version of Manning’s message. But were Canadians ready for him? Would they take seriously this rather prim introvert in badly cut suits, whose speeches consisted of reasoned arguments and to-do lists rather than soaring rhetoric?

The first test came at a gathering of the newly formed Reform Association of Canada in Vancouver in May 1987. Carefully devised by Manning, the event was billed as two days of lengthy discussions to develop “A Western Agenda for Change.” Behind the podium, a large banner proclaimed, “The West Wants In.” Over five hundred people from all four western provinces were happy to vent against central Canada.

At first, central Canada was less impressed. Manning had invited Prime Minister Mulroney to send a representative to Vancouver. “Mulroney sent a short, snarky response, saying he would forbid any of his members to attend.”21 Taking its lead from the Mulroney government, the Ottawa press gallery dismissed Manning as just another whining westerner and dubbed him “Parson Manning.” Craig Oliver, chief political correspondent for the CTV network at the time, recalls that Manning’s “utter faith in the rightness of his views and the conviction with which he expressed them seemed very like sermons from the pulpit.” It wasn’t just that Manning sounded like a preacher. He still was a preacher; his Christian faith was and remains a crucial part of his life. Similarly, Alberta Report promoted very conservative Christian values relentlessly. But for the secularized, irony-soaked Toronto intelligentsia, it was a bit much.

No matter. By the end of the Vancouver meeting, Preston Manning had got what he came for. Delegates voted to establish a new, broadly based federal political party with its roots in the west, which had moved beyond grievance toward demands for debt reduction and democratic accountability. In an anti-Quebec swipe, Manning supporters agreed that no province should have special status. Soon the new party was christened the Reform Party of Canada, and Manning had been elected leader.

The party had a slow start. In the 1988 federal election, all the Reform Party’s candidates were defeated, and the party won only 2 percent of the vote. (Even in Alberta, it managed to get only 15 percent.) However, the “West Wants In” movement had smothered the cranks who were demanding that the West get out. “Reform was the relief well for that wildcat flow of separatism,” comments Manning. “We channelled the energy into making the federation work better rather than kicking it apart.”22

Manning methodically grew his party. He dropped the western rhetoric and began to talk of “Old Canada” and “New Canada” as he criss-crossed the country. His slight figure, with wire-rimmed glasses on his nose and a prairie twang in his voice, turned up in small-town halls and church basements, with little advance publicity other than handwritten notes nailed to telephone poles or circulated in general stores. The crowds seemed to appear out of nowhere to hear him talk about stuff from a viewpoint that they weren’t hearing elsewhere, and to voice views that were barely admissible within mainstream parties. Manning’s followers were tired of soaring federal deficits and feverish debate about keeping Quebec in Canada. They cheered Manning’s denunciations of the policies of bilingualism and multiculturalism; they applauded his calls for an elected Senate, referendums, equality between provinces, and “bottom-up democracy” (whatever that meant). Many meetings ended with a passionate rendition of “O Canada.” For all Manning’s talk of New Canada, his audience—disproportionately older, male, and rural—looked awfully like Old Canada, nostalgic for simpler, more God-fearing times.

Manning lacked Tommy Douglas’s oratorical magic. Yet Reform’s appeal was unmistakable as it steadily rolled eastward into Ontario, surfing on the growing unpopularity of Brian Mulroney’s Tories. Even if much of Reform’s platform was dismissed by critics as naive, Manning’s movement carried none of the historical baggage of the three established parties. In an era of unprincipled or bumbling politicians, nobody questioned Preston Manning’s integrity.

By 1990 Canada’s federal debt was swelling and some of Bible Bill’s despised “high mucky-mucks” in the East decided that Manning was the only political leader paying attention to the crumbling economy. Preston Manning was invited to a private dinner hosted by the publisher Conrad Black and the financier Hal Jackman in their plush sanctuary, the Toronto Club. He explained to fifty financial heavy hitters that his party would ask voters to choose between Old Canada and New Canada. “Old Canada is a Canada where governments chronically overspend and where there’s a constitutional preoccupation with French and English relations. In New Canada, governments would be fiscally responsible and we’d go beyond French-English relations as the centrepiece of constitutional discussion.” Old Canada, sitting right in front of Manning and puffing cigars, “inhaled the words ‘fiscally responsible’ like a narcotic,” according to Ian Pearson in Saturday Night magazine. The fifty big shots present that night gave Manning a standing ovation.23 The western champion of “ordinary Canadians” had successfully recruited corporate support.

The first major gains for Reform came in the 1993 federal election. That election redrew the electoral map of Canada because the Progressive Conservative Party fell apart. While Jean Chrétien’s Liberals swept into government, only two PCs were elected. Two upstart parties—Alberta-based Reform, and the separatist Bloc Québécois—picked over the PC carcass. The Bloc won fifty-four seats, catapulting it onto the official opposition benches, while Reform, with more votes, was hot on its tail with fifty-two seats, all but one in the West. Preston Manning was elected as the honourable member from Calgary Southwest, and one of his closest advisers, a young economist called Stephen Harper, won Calgary West.

Reform overtook the Bloc Québécois in the 1997 election. The Liberals under Jean Chrétien once again coasted to victory, thanks in part to a divided opposition. But Reform won sixty seats—all in western Canada—and Preston Manning became the leader of the official opposition.

It was a stunning achievement. Within a decade, Preston Manning had cannily steered his regional protest movement onto the national stage. The Reform Party had become Canada’s major right-wing party and started to win votes, but no seats, in Ontario. There was still no sign that it could ever form a government; its share of the vote remained below 20 percent, and it had no support in Quebec and no MPs from east of the Lakehead. In an era of ethnic and gender equity, party membership was dominated by English-speaking older white men.

Nevertheless, Preston Manning had pushed his version of conservative values into the mainstream. Public accountability and government debt were now concerns from coast to coast; spending and tax cuts, and the privatization of social services, were part of political debate. By and large, he had managed to shut down the anti-gay, anti-abortion, anti-government crazies in his party. (“If you turn on a light, you’re going to attract bugs,” he reflects.) He had broken the mould of traditional two-party politics and succeeded, he hoped, in achieving Frederick Haultain’s 1903 goal of creating a strong western block that could challenge the centre.

Manning’s sense of timing had been spot-on. The Reform Party was born amid the constitutional conflicts of the 1980s, and the political fault lines of this large and unwieldy country zigzagged across the map. Throw in the visceral distrust of Brian Mulroney, the passions aroused by the 1988 free trade deal with the United States, high unemployment, and rampant inflation, and you have a toxic mix. As Keith Spicer, chair of the Citizens’ Forum on Canada’s Future, noted in the group’s 1991 report, there was “a fury in the land.” The national angst didn’t subside after the Liberal electoral victory of 1993, because only two years later, Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty. The separatist forces came within a heartbeat of winning.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t just about timing. As Craig Oliver admits, “We in the media don’t always recognize a game changer when we meet one.”

Those who come to Canada’s national capital to participate in the business of government see Ottawa very differently from the way that long-time residents experience the city. Lifers enjoy stable house prices, free-flowing traffic, and a seasonal rhythm of skating on the Rideau Canal in winter and hiking in the Gatineau Hills in the summer. We love the Gothic Parliament Buildings as a landmark—a glorious Victorian gesture of optimism about the fragile new Dominion’s future—but we rarely stroll across the grounds. We relish the big-city amenities (national museums, the National Arts Centre) but we cherish the homey atmosphere of our neighbourhoods.

In contrast, those who come here for politics—MPs, reporters, and eager young staffers—are often leery of a city that is periodically convulsed by scandal and tagged a “fat cat.” New arrivals stick close to the parliamentary precinct and the surrounding palisade of government offices. Their loyalties are defined by their Sparks Street hangouts: their preferred reading is the Hill Times; they watch question period every day. Ottawa is not home: the Ottawa Senators are not their team. Most have no intention of settling here. MPs who commute home for weekends know the featureless road to the airport better than they know the colourful Byward Market.

Leaving Sandra and the family in Calgary, newly elected Preston Manning arrived in Ottawa in 1993 with an outsider’s distrust of an established institution. During his first term in Parliament, he stayed in a drab room in the downtown Travelodge. He visited the museums or the National Arts Centre only for government functions. Ottawa felt to him, he recalls, “like the capital of a nineteenth-century British colony. Even the flags were scrawny: Husky Oil gas stations out west have bigger, better Maple Leaf flags.”24 He regarded the flexibility required to balance the federation as symptoms of “Ottawa fever.” Not only did the politics of compromise offend his fundamentalist principles, they also fed into his sense that, once MPs arrived in Ottawa, they too easily forgot why they were elected. “First the memory starts to go. Sufferers forget all those commitments that were made during the election. Then it’s the hearing. . . . It gets harder and harder to hear the voices of the folks back home. After a little while the head starts to swell, and that can be fatal.”25

Manning was determined to challenge every long-standing parliamentary convention. Reform, like Social Credit before it, presented itself as a “movement” rather than a morally compromised political party like the Liberals and the PCs. He sat on the second row of opposition benches to illustrate that there would be no hierarchy of frontbenchers and backbenchers; he renamed the party whip the caucus coordinator to avoid the traditional term’s “authoritarian connotations.”26 As leader of the official opposition, he refused the keys to his official limousine and to Stornoway, the official residence. (He later relented when he realized this would put the driver and staff out of jobs.)

But the longer Manning remained in Ottawa, the more apparent it became that he could never be prime minister. Television made demands on politicians that the Fathers of Confederation never faced. On screen, “Parson Manning” came over as too earnest, too dull, and a magnet for mockers. “In the beginning, I was loath to give this subject much of my time,” he admits, but under pressure from advisers he submitted to an upgrade: capped teeth, laser eye surgery, and a voice coach to iron out the squeak. Next came his wardrobe. “We started with the ties, enlisting the help of a ‘tie consultant.’ . . . There was the ‘power tie’ . . . the ‘come-hither tie’ . . . the ‘back-off tie.’ . . . We bought them all, but the problem was that I couldn’t remember which tie did what.” Reporters warmed to him when he made a very funny speech about the makeover at the annual press gallery dinner. But that was not enough. His religious convictions and Prairie Home Companion style did not cut it for young, urban Canadians.

Far more significant than dearth of charisma was his attitude to Quebec. It wasn’t simply that he didn’t speak French. Steeped in western alienation, he showed little sympathy for a province with a unique cultural and political legacy that predated Confederation and that it wanted to protect. Every political strategist in Canada knows that to form a government, a party must win two out of three regions: Quebec, Ontario, and the West. (Atlantic Canada can mean the difference between a minority and majority government, but there are too few seats to guarantee a government.) This was why party leaders since the days of John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier have spent so much time balancing the interests of different regions: this is how brokerage politics evolved. But Manning’s attitude ensured not only that he could never win any seats in Quebec, but also that his prospects in Ontario—where voters cared about national unity—were significantly reduced, and that he had no resonance in the Atlantic provinces. “He is a conviction politician,” says the political strategist Robin Sears, “and there is a big gap to navigate between principles and power.”

In fact, the only way that Reform could get a whiff of real power was if Quebec did separate. Jean Chrétien, prime minister at the time, suspected that “Manning knew he could never become prime minister of Canada because of Quebec and, consequently, that he wouldn’t have been terribly sorry to see it leave the federation.”27 The fact that its departure would leave Canada looking like a doughnut, with a big hole in the middle, was not discussed by the Reform leader. Instead, he suggested that if “the people of Quebec and the people of the rest of Canada” were properly consulted about his New Canada, they could “be reconciled.”28

By the 1990s Manning’s railing against government debt had helped build public acceptance for the belief that government spending must be cut. This made it much easier for the Liberal government to pass a tough budget in 1995 and straighten out the nation’s finances. At the same time, constitutional fatigue had set in: nobody wanted to talk about rebalancing federal powers. Reform’s populist tide and Manning’s personal popularity began to ebb.

Manning recognized that he needed to attract a broader range of conservatives, particularly in Ontario. First he renamed his party the United Alternative; soon this transformed itself into a new party, the Canadian Alliance, with a platform that combined Reform and Progressive Conservative policies. (Brian Mulroney branded it “the Reform Party in pantyhose,” and most seasoned PCs refused to join.) But at the Canadian Alliance’s first leadership convention, in 2000, Manning was shocked to find himself cast aside in favour of a younger, more “electable” leader who might win votes in Ontario. Manning’s immediate successor, Stockwell Day, quickly became a laughingstock after his evangelically inspired views on evolution were skewered on national television. Craig Oliver recalls the internecine struggle to oust Day as “a circus of intrigue and betrayal.”

To Manning’s distaste, the Alliance then merged with the remnants of the old Progressive Conservative Party, in 2003. Within a remarkably short time, Manning’s one-time policy adviser Stephen Harper had elbowed aside all comers, won the leadership of the Canadian Alliance, and taken the helm of the new Conservative Party. The word “Progressive” was flung into the trash can.

The fiscal policies that Manning’s Reform Party pushed were part of the late-twentieth-century wave of conservative economics sweeping Europe and North America: Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan gave Manning an intellectual respectability that he didn’t have in the 1970s. However, it was Manning who had strengthened the ideological spine of Canadians on the conservative side of the political spectrum. “Nobody in Canada was talking about balanced budgets until Preston Manning put them on the map,” argues Tom Flanagan, who worked alongside Stephen Harper as a policy adviser to Manning. Flanagan is an American academic who served as head of the political science department at the University of Calgary until 2013, and who was a conduit of American neo-conservatism into the Reform Party since its birth. “He pushed the issue to the top of the Conservative agenda.” Manning reframed the economic debate in a way that portrayed government as spendthrift and corrupt, making it difficult for any politician to discuss tax hikes or social programs.

Without the Reform Party and Preston Manning, Stephen Harper would never have become prime minister of Canada; he had neither the patience nor the personality to build a party from scratch as Manning had done. But he won three federal elections, which gave him two minority governments and one majority government. Once installed at 24 Sussex Drive, he stuck as close as he dared to the Manning agenda.

Harper championed trade liberalization, balanced budgets, lowered taxes, and constrained government spending (although the 2008 global economic crisis forced some deviation from Reform dogma). He moved the policy yardsticks rightward on foreign policy, criminal justice, and civil liberties. He re-engineered the federation by leaving the provinces to run their own health care, environmental, and education programs with little federal co-ordination or intervention. Canada reduced its support for multilateral organizations like the United Nations and for aid to less developed countries. Its official indifference to climate change debates made it an outcast internationally.

Some of this was straight cost-cutting. But many of the changes went way beyond the Manning legacy and were driven by more than a determination to reduce Ottawa’s power. Harper wanted to challenge the Liberal monopoly on values that defined Canada: universal health care, peacekeeping, Charter freedoms, and diversity. His campaign to slash Ottawa’s powers included direct attacks on institutions and programs that postwar Liberal governments had established to bind the country together, from the national broadcaster to university exchange programs. Harper tried to reinforce in the Canadian psyche overtly right-wing values, including a new respect for the monarchy and the armed forces, and an emphasis on military victories and sacrifice.

Harper had little patience for accountability or Manning’s precious “bottom-up democracy.” In Manning’s words, “Stephen was never prepared to be a team player, [and the two minority governments] . . . reinforced his tendency toward iron control.”29 The goal of building a populist party that directly involved members in policy-making was doused by the hard reality of the deals required to govern Canada. It was always an unrealistic goal, according to Flanagan, who had left Manning’s office and gone to work with Stephen Harper. “That’s too unwieldy within our system. What you need in national politics is an armoured division, not a populist party. ‘Top-down’ wins in Canada.”

The founder of the Reform Party watched his former lieutenant operate with an autocratic ruthlessness that shocked many supporters. In 2015 the National Post columnist Conrad Black, no friend of the Liberals, berated Harper for governing the country like “a sadistic Victorian schoolmaster.”30 In the election a few days later, Stephen Harper was defeated. Among the 5.5 million Canadians who stuck with the Conservatives (32 percent of all voters), the vast majority were older white westerners—the original Reform Party supporters.

After the election I asked Preston Manning if he felt Harper had betrayed his legacy by abandoning Reform Party populism and running such a top-down government. “I wouldn’t use the word ‘betrayal,’ ” replied the former leader of the Reform Party. “And I never like to talk about legacies. If you keep looking in a rear-view mirror you’ll run into a tree.” Manning is philosophical about his own failure to propel his creation to power. As he tells me over the telephone, “The first people to scale the walls of any fortress are those who get hot oil poured on them. It is usually the third wave that makes it.”

How did Preston Manning affect the promise of this still young, still growing nation?

He demonstrated the continuing appeal of populist movements within Canada, and he achieved a larger role for the West in our public life. Despite his aversion to “Ottawa fever,” Manning was always committed to the idea that Canada is built on mutual accommodation among regions and interests; his objective was to change the terms of the accommodation. Almost single-handedly, he doused the flames of western separatism in the late 1980s. A decade later, he did not endorse the letter, signed by Stephen Harper among others, suggesting the construction of a “firewall” around Alberta to protect the province from Ottawa. Manning himself says that one of Reform’s most important contributions is that “we shifted the geopolitical centre of gravity from the Laurentian Basin towards the West. The West cannot be taken for granted anymore.”

At the same time, Preston Manning widened the political debate within Canada by destroying the old Progressive Conservative Party and spawning a much more right-wing option. He is a devotee of American political history, and many of his ideas have a distinctly Republican flavour—particularly distrust of the federal government. He likes to take credit for the fact that, in Canada today, “trade liberalization and balanced budgets are conventional wisdom. The new guys will be measured by those yardsticks.”

But there is a more paradoxical way in which this Albertan has shaped our country. He clarified the choices ahead as Canada embarks on the next 150 years.

Preston Manning offered Canadians a different kind of Canada, a country of more modest ambitions that quietly minded its own business and looked to market forces rather than government for leadership. When I asked him what holds Canada together today, he offered only, “Democratic values and inertia. Nobody wants to make the effort to kick it apart.” This narrow outlook is a stark contrast to the grand vision articulated by George-Étienne Cartier and John A. Macdonald in 1867, on which they based the new Dominion and with which subsequent prime ministers, from Wilfrid Laurier to John Diefenbaker, from Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau to Brian Mulroney, have rallied the country. It is also a contrast to the “Never say ‘Whoa!’ in a mudhole” optimism of which most Albertans are so proud.

In the 2015 election, the electorate voted against the limited vision offered by Manning and his protégé Stephen Harper. They had tried to lead Canadians in a different direction, and the majority of Canadians refused to be led. Harper’s successor, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, had campaigned on Canada’s enduring potential with the line “In Canada, better is always possible.” He emerged with a majority government, including MPs from every province and territory.

When the new prime minister and his cabinet were sworn into office by the governor general, I joined the several thousand people who streamed through the open gates onto the grounds of Rideau Hall. On an unseasonably sunny November day, we watched our new government promenade up the drive. It was like a carefully choreographed Hollywood moment as the youthful leader sauntered forward at the head of a team that was the personification of inclusiveness. This looked much more like the “New Canada” than Manning’s definition of this phrase when he was building his party. Half the new ministers were women; top posts had gone to Indigenous Canadians and people from several non-traditional immigrant groups; one of the ministers had arrived here as a refugee from Afghanistan less than twenty years earlier. Next to me, in the crowd of spectators, women in hijabs posed for photos with Trudeau, and cab drivers in turbans held toddlers up to see him. Despite the regional, linguistic, and ethnic tensions, at that moment the country seemed extraordinarily united.

Preston Manning’s failure to become prime minister, followed by the Trudeau victory, has not blunted the former Reform leader’s evangelical urge to engage the grassroots in the political process. After he retired from federal politics in 2002, Manning turned his attention back to building a new conservative movement from the grassroots up. “Something has got to be done to get the democratic juices running again,” he explains. “If you can’t change the system, can you raise the calibre of the people in it?” In order to encourage more widespread participation in public life by those who share his views, he founded the Calgary-based Manning Centre, which runs annual conferences for conservatives and offers training courses in political activism. “These are the kinds of reforms that might restore public confidence in the system,” he explains.31 Robin Sears predicts, “His influence will be this last chapter, with his calls for a more principled approach to politics.”

Today Preston Manning is busy promoting a conservative response to environmental damage. “The argument I like to make,” he explains, “is that core ‘conservative’ values include ‘conservation.’ Living within our means is a conservative concept. We should extend the concept to its ecological conclusion—we should live within our environmental means.” Such a statement has won him surprising supporters: Margaret Atwood dubbed him “Man of the Future” in the National Post.32 Manning continues to argue that solutions to global warming should be left to market forces rather than federal initiatives. “Why not harness pricing mechanisms to mitigate environmental destruction?” This approach may be far too gradual, given the speed of climate change. But at least Manning is talking about the issue within circles where some prefer to ignore it.

Preston Manning’s reputation is not mortgaged to the death of the Reform Party. When he speaks at a university, the lecture hall is full. When he walks through an airport, strangers shake his hand. Mention his name, and Canadians who would never have voted for him will often admit affection for this westerner with a preacher’s drawl, and agreement with some of what he writes these days. “He has mellowed in his old age” is a common sentiment. Perhaps. Or perhaps, over the past two decades, the centre of gravity in Canadian politics has shifted toward him.

I asked Manning what he thought of the 2015 election result, as I had asked him his reaction to the result of the election in Alberta earlier in the year. “I wasn’t really surprised,” he responded, in the now familiar nasal drawl. “You shouldn’t read too much into the Conservative Party’s defeat. The standard life of a government in this country is nine years: after that, it is always living on borrowed time. And the core Conservative vote held.”

And in Canada, regional pressures never disappear. Preston Manning continues to watch and wait. “Justin should enjoy the ‘swearing in,’ ” he tells me, “because, as my dad used to say, the ‘swearing at’ soon begins!”