War came to Lae on 21 January 1942. The German settlement of Lae, assigned to Australian control with the rest of German New Guinea after the First World War, would now be a key objective in the Second World War. Just before midday Lloyd Pursehouse, a Coastwatcher at Finschhafen on the north-eastern coast of New Guinea, reported that about 60 enemy aircraft were flying west along the coast towards Lae. As the air raid siren rang out across Lae the Japanese fighters came in from the sea and strafed the township and adjoining airfield. A large formation of bombers followed, dropping their loads across the town, after which the fighters continued their strafing. The raid left the Guinea Airways hangars, workshops and stores as well as the power plant completely destroyed and many other buildings damaged. Before the war Lae airfield had been the supply hub for extensive gold mining operations and the valuable runway was deliberately left intact though five aircraft were destroyed. Fortunately Pursehouse’s timely warning had prevented any casualties.1

One Junkers transport piloted by Bertie Heath managed to take off before the raid and reach Bulolo carrying a load of beer. He was initially waved off while obstructions were cleared from the airfield so that he could land. However, it was only a temporary reprieve for Heath as ‘five Japanese Zeros arrived hedge hopping with the sound of angry bees’. The Zeros began flying back and forth, strafing the three Junkers transports on the airfield. The seven New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (NGVR) guards at the airfield soon depleted their few Lewis gun magazines to no effect and could only watch on as the three Junkers aircraft burned.2

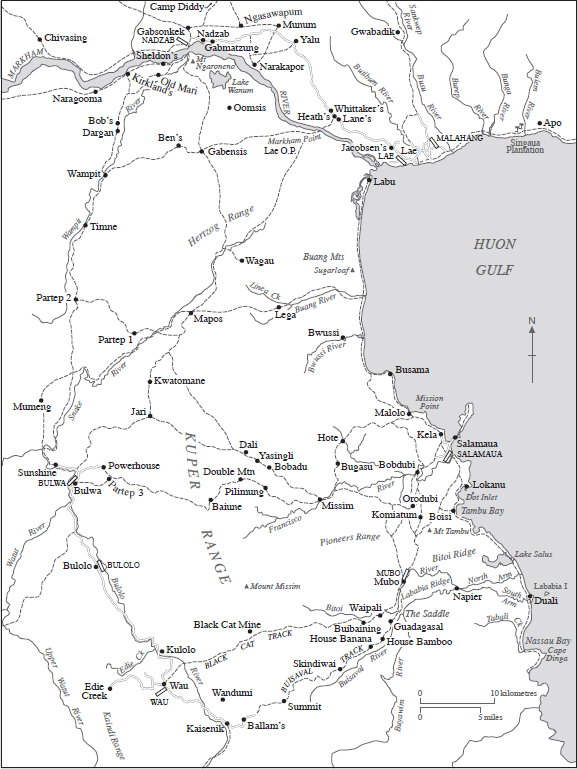

Other raids hit Salamaua, on the coast 40 kilometres south of Lae, and Wau which was 50 kilometres inland from Salamaua (see Map 2). Lloyd Pursehouse and the airfield guards at Bulolo typified Australia’s role in the opening months of the war in New Guinea. Given the almost total neglect of the responsibility for defending the islands to the north of Australia, the Australian government and people were reduced to the role of hapless observers as the Japanese moved south.

•

After the air attacks of 21 January a Japanese landing was considered imminent and it was decided that the government and civilian population should immediately be evacuated from Lae to a hidden position further inland. Under NGVR supervision, all available motor transport was assembled to move foodstuffs and other goods from the Burns Philp store and the airfield, and this work continued throughout the night. The stores were temporarily distributed along the Markham Road west of Lae in various houses and under tarpaulins in the bush. The work was hampered by heavy rain, which rendered the road practically impassable beyond 8 kilometres from Lae.3

Map 2: Lae–Salamaua area, 1942–43

At this stage the total strength of the NGVR and attached personnel in the Lae area was twelve officers and 327 other ranks under the command of Captain Hugh Lyon. On 27 January authority was granted to compulsorily call up all males of European origin between eighteen and 45 years of age for military service unless required for essential services. Within three days 87 new recruits were enrolled and fifteen men of Chinese and Malay origin were also enrolled for transport and medical duties. The men added 2000 to their enlistment numbers so the Japanese would later overestimate the unit’s strength.4

Instructions had been received from Port Moresby to prepare Lae, Salamaua and Madang aerodromes for demolition and a former miner was sent to each centre to prepare the explosives. However, all aerodromes were to remain open until the evacuation of civilians was completed while Salamaua airfield was still required by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) for operational purposes. Once the expected Japanese landing at Lae occurred, the intention was to hold a line from Gabensis to Wampit and to prevent the Japanese from entering the foothills behind Lae. If the Japanese entered the Markham Valley west of Lae, harassing tactics were to be adopted. On 2 February the NGVR detachment at Lae was instructed to transfer all stores to the south side of the Markham River near Nadzab at the earliest opportunity.5

Meanwhile the observation game continued. On 5 February the Lae detachment was instructed that the radio transmitter was not to leave the coastal area under any circumstances, as it was the only means to inform Port Moresby of an enemy landing. A section including three signallers was to proceed immediately with a radio transmitter to a point in the ranges south of Lae to establish an observation post overlooking the Huon Gulf from Lae to Salamaua. Sergeant Stan Burton was one of the NGVR signallers taken by boat from Lae to a point south of the Markham River below the Buang Ranges to set up the observation post on a prominent position known as Sugarloaf. The Amalgamated Wireless Australasia 3A radio was designed to be used from a static location and it took twelve men to move the radio, batteries, charger and fuel to the new site. From a lookout point in one of the trees on the coastal side of the mountain, both Lae and Salamaua could be easily observed and any information radioed back to Port Moresby.6

On 13 February the NGVR strength in the Lae and Buang areas was five officers and 89 other ranks, mainly equipped with rifles and grenades, but also with two Vickers machine guns, five Lewis light machine guns and eight Thompson sub-machine guns. In the Salamaua area there were four officers and 74 other ranks similarly equipped. Units in both areas were widely separated and communications were difficult. In the Wau, Bulolo and Bulwa areas there were another 230 NGVR troops although less than half were considered adequately trained and about 10 per cent were ill.7

•

Despite the expectation that the Japanese would follow up the capture of Rabaul with an immediate landing on mainland New Guinea, that was not their plan. The first concern for the Japanese command in Rabaul was to capture the airfield at Gasmata on the southern coast of New Britain. An invasion force and support group left Rabaul at dawn on 8 February under heavy rain cover and made an unopposed landing early on the following day at Gasmata. The airfield was long enough to service carrier-based fighters and the first Japanese aircraft landed there on 11 February. The airfield would have great value for future operations against mainland New Guinea.8

On 16 February the chief of staff of the Japanese South Seas Force, Lieutenant Colonel Toyonari Tanaka, travelled to the Japanese naval base at Truk to meet with the commander of the Fourth Fleet to finalise the invasion plans for Lae and Salamaua.9 The Fourth Fleet would provide an invasion force with a strong naval escort and air cover. A special naval landing force battalion, the 8th Base Force of about 620 men, would be landed from five transport vessels at Lae while Major Masao Horie’s 2/144th Infantry Battalion from the South Seas Force would make the Salamaua landing from two transports. The entire force would depart Rabaul three days before the landing date, tentatively scheduled for 3 March.10 However, on 20 February a US aircraft carrier task force approximately 740 kilometres northeast of Rabaul launched aircraft against the Fourth Fleet, delaying the planned landing until 8 March.11 Despite the presence of the US Navy, the wretched lack of Australian military preparation in New Guinea meant both Lae and Salamaua were there for the taking and the Japanese knew it.

The invasion force left Rabaul at 1300 on 5 March, and at 1255 on 6 March the convoy was spotted by Allied aircraft off the southern New Britain coast west of Gasmata heading towards mainland New Guinea. Early on the morning of 7 March the convoy, made up of one cruiser, four destroyers and six transports, was again sighted east of Lae but that night the naval and army components of the force divided, bound for Lae and Salamaua respectively. The army transport fleet encountered a violent storm when it entered the anchorage area to the east of Salamaua but the landing barges were lowered at 2300, with boarding completed by midnight. Major Horie’s battalion landed unopposed at 0055 on 8 March and two hours later Salamaua airfield had been successfully occupied.12

On that morning of 8 March the men at the Sugarloaf observation post reported that four vessels were approaching Lae and five others were heading for Salamaua. Without access to codes, the message to Port Moresby had to be sent in clear English. ‘We were disappointed to sit and watch their unloading of cargo etc. without them being attacked by our planes,’ Stan Burton noted.13 Marines of the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force landed south of Lae at 0230 and occupied the airfield and township unopposed. Work on repairing Lae airfield commenced later that same morning, with preparations for its use as a fighter base completed by 1300 the following day, 9 March. Three RAAF Hudson bombers were sent to attack the Japanese landings but were only able to damage the destroyer Asanagi.

•

It would be left to the United States Navy to do more than just observe the relentless drive of the Japanese south towards Australian shores. Early on 10 March, aircraft from the two US aircraft carriers Yorktown and Lexington made more serious attacks against the Japanese anchorages at Lae and Salamaua. Vice-Admiral Wilson Brown launched his attack from 70 kilometres off the southern Papuan coast, across the imposing cloud-shrouded Owen Stanley Range. This ensured the safety of the carriers from Rabaul-based strike aircraft but set a daunting task for the heavily laden aircraft to cross the mountains.14 There were 104 aircraft in the strike force, 25 Devastator bombers, twelve of them carrying torpedos, 61 Douglas Dauntless dive bombers and eighteen Grumman Wildcat fighters. The fully laden aircraft struggled to cross the Owen Stanley Range but were helped by Commander William Ault, from the Lexington’s air group, who positioned his scout plane over the pass in the range to guide them through. Commander Jimmy Brett, the Lexington torpedo squadron chief and a former glider pilot, found an area clear of jungle and, circling above it, found a thermal updraft that gave him enough altitude to get through the pass. His squadron followed.15

At Lae the Dauntless bombers hit three ships, sinking the 8600-tonne armed merchant cruiser Kongo Maru and forcing the 5400-tonne converted minelayer Tenyo Maru aground off the end of Lae airfield. Seven other vessels were damaged. One Dauntless was shot down over the Huon Gulf, the only aircraft lost in the raid. The converted minesweeper Tama Maru No. 2 was also sunk at Lae and the transport Yokohama Maru was sent to the depths off Salamaua.16 Three other vessels, the Yûnagi, Kôkai Maru and Kiyokawa Maru, were significantly damaged. The Japanese lost 132 men killed and another 257 wounded during these air raids.17

A few days after the landing, Japanese aircraft circled the NGVR observation post at Sugarloaf, apparently now aware of its existence. The observers therefore decided to move the post some 5 kilometres further up the mountain to the west. This move came none too soon as Japanese troops reached the camp the next morning, destroying everything including the food supplies. The men then had to walk out to the west via a sago swamp before contacting some natives who led them out to Sunshine camp in the Bulolo Valley. On arrival, one of the men at the camp exclaimed ‘Hey fellows! Have a look! Jesus Christ and some of his disciples have just walked in.’18

•

The first aircraft from the Japanese 4th Naval Air Corps landed at Lae on the afternoon of 10 March, too late to have any impact on the devastating American air attacks. About half the strength of this air corps had moved to Lae, tasked with patrolling the Coral Sea area and attacking Port Moresby. On 14 March, nine bombers attacked Port Moresby, while eight bombers escorted by twelve Zeros made their first attacks on Australian soil, targeting Horn Island. Although six bombs hit the Horn Island runway, none of the Hudson bombers based there were hit.19

The Royal Australian Air Force was also busy. On 21 March seventeen P-40 Kittyhawks of RAAF No. 75 Squadron landed at Port Moresby despite ‘friendly’ fire from Australian machine-gun posts. The following day Squadron Leader John Jackson led nine of the Kittyhawks in a surprise dawn attack on Lae, catching the Japanese aircraft lined up wingtip to wingtip along the runway.20 Five Kittyhawks made two passes each over the airfield while four others provided top cover. Virtually the entire contingent of Japanese planes at Lae, nine Zeros and one bomber, were strafed on the ground and caught fire, while two other Zeros were shot down.21 One of the Kittyhawks was downed by anti-aircraft fire, and the pilot, Flying Officer Bruce Anderson, was killed. Three Zeros attacked the top cover, and one of the Kittyhawks, piloted by Flying Officer Wilbur Wackett, son of the Australian aviation pioneer Lawrence Wackett, was shot down over the Huon Gulf. Wackett managed to swim to shore near Busama on the coast between Lae and Salamaua and, with the aid of two selfless local guides, made it to the Bulolo Valley four days later. He then trekked to the south coast along the Bulldog Track, and ultimately made it back to his squadron. The Japanese riposte came on 23 March when nineteen bombers escorted by three Zeros attacked Port Moresby.22

More aircraft were moved to Lae in early April when most of the 45 fighters and six reconnaissance planes of the Tainan Air Group arrived. The 30 Japanese naval fighter pilots at Lae under the command of Captain Masahisa Saito were the cream of the crop, among them the ‘Devil’, Lieutenant Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, who would become the war’s leading Japanese air ace.23 Meanwhile the Kittyhawks of No. 75 Squadron kept up the attacks on Lae, destroying two and damaging eight Zeros and nine bombers on 4 April. Over the following days the Japanese hit back with attacks on Port Moresby but heavy losses caused the bombers at Lae to evacuate to Rabaul on 11 April. Commander Sadayoshi Yamada of the 25th Air Flotilla lamented that ‘The number of serviceable aircraft for attacks on Port Moresby on 14 April did not exceed three fighters and three attack planes.’ Meanwhile low-level United States Army Air Force (USAAF) bomber raids on Rabaul took a toll. On 9 April Rear Admiral Masao Kanazawa, commander of the 8th Base Force, wrote in his diary: ‘Suffered a severe raid … Conspicuous signs of defeat in the air war.’24

On 10 April, as John Jackson carried out an early morning reconnaissance flight over Lae and Salamaua, the Japanese airmen were waiting for him. The Japanese maintenance crews at Lae had begun preparing the Zeros at 0230, and by 0330 the pilots were awake. Following a sparse breakfast, six pilots waited by the warmed-up planes, ready to scramble.25 When Jackson’s aircraft was spotted, three Zeros were scrambled, forcing him to jettison his extra fuel tank and try to use his speed to get away. He soon realised he would not be able to outrun the Zeros, but when he turned to fight he found his guns had been hit and would not work. Outnumbered and defenceless, Jackson’s plane was soon riddled with gunfire and he had no alternative but to ditch the plane into the sea, about 1 kilometre from shore. The Kittyhawk quickly sunk and, with the three Zeros circling, Jackson lay in the water, feigning death. Like Wilbur Wackett he was fortunate enough to be helped by local natives who alerted NGVR troops at Wau, from where he was flown back to Port Moresby on 23 April.

•

By 1 April the NGVR troops at Lae had moved to the comparative safety of the south side of the Markham River. Supply dumps and staging posts had been established at Sunshine, Mumeng and Partep leading from the Bulolo Valley down to the Markham River. These posts enabled the NGVR to maintain a detachment at Gabensis and an observation post at Sheldon’s camp opposite Nadzab. The Partep post had the secondary advantage of being on a dominant hill position from which any Japanese move across the river and up the Bulolo Valley could be countered. A native swam the Markham River and reported that the obstacles that had been placed on Nadzab airfield were still in place and Gabsonkek village was unoccupied.26

Rifleman George Wharton made a canoe trip down to the mouth of the Markham to confirm the Japanese had not crossed the river to Labu. He also observed smoke which indicated that a line of Japanese outposts had been set up at Jacobsen’s and Emery’s plantations about 3 kilometres out along the road from Lae. Native scouts also told Wharton that Malahang airfield, on the eastern outskirts of Lae, was not being used and that three barracks buildings had been constructed in Lae. In late April Wharton found an ideal observation point above Labu village which provided an excellent view over Lae, Salamaua and the Huon Gulf. All aircraft take-offs and landings from Lae could be clearly seen, though the airfield itself was blocked by tree growth.27

Major Bill Edwards, who had worked as a doctor with Guinea Airways before the war, was the NGVR area commander at Lae. On 9 April he crossed the Markham and set up his headquarters at Nadzab before moving to the edge of the valley flats on the track to Boana. This new camp, some 18 kilometres north-west of Lae, was code-named Diddy (see Map 3) and had a milking cow, cattle and sheep as well as stoves for baking bread.28 Stan Burton moved to Diddy camp as a radio operator, passing on information about the Japanese base at Lae.29 That information would come from small patrols to observation posts set up around the outskirts of Lae. Lieutenant Phil Tuckey and six men established such a post on a ridge overlooking Heath’s Plantation, approximately 10 kilometres west of Lae on the Markham Road.30 The Japanese had established a small outpost there.

The most important observations involved the movements of Japanese aircraft at Lae. Following the earlier Allied air attacks on Lae the Japanese now started up their fighters before dawn and maintained a constant watch all day with at least two fighters at high altitude patrolling a radius of some 8 kilometres out from the airfield. Lieutenant Bob Phillips and two other men boldly scouted right up to Lae airfield where they observed the exact location and identification numbers of 27 fighters and four large two-engine bombers, a number of which had been camouflaged with foliage. There were 100 men working on the airfield and their arrival and departure times for the workday were also noted. Buildings, storage tanks and bomb dumps were also spotted along with a bulldozer and five large trucks, one doubling as a petrol tanker. Meanwhile local natives provided information on the location of anti-aircraft guns at Lae airfield, Jacobsen’s Plantation, Mount Lunamun and the Busu River.31 Back in Port Moresby, the commander of New Guinea Force, Major General Basil Morris, expressed his delight with the valuable intelligence from Bob Phillips’ patrol.

•

On 12 April Lieutenant Roy Howard from the 1st Independent Company had arrived at Bulwa after travelling overland from the head of the Lakekamu River on the south coast to Wau via the daunting Bulldog Track. Howard brought a platoon of some 50 men with him. On 19 April it was suggested that no action be taken against the enemy in the Salamaua area until the forces in the Lae area were ready to undertake a similar action, thus ensuring surprise.

Sergeant Bob Emery had been in Lae since 1934, first working at Carl Jacobsen’s plantation and then taking up his own allotment between Jacobsen’s and the Butibum River. By 1941 he was running the local dairy, using cattle he had brought up from Australia. A number of Lae men had joined the AIF (Australian Imperial Force) and went off to fight, but Emery was loath to abandon his farm so had joined the local NGVR militia. As war came closer, Major Edwards asked Emery if he would go to Madang with two other soldiers, Dick Vernon and Peter Monfries, and a dozen native policemen to help guard the airfield there.32 Emery was still at Madang when the Japanese captured Lae but was soon ordered back, arriving at Diddy camp around 1 May.

The NGVR troops at Diddy camp were brazenly using a truck by day to bring supplies from Nadzab to Ngasawapum from where the cargo could be carried up to Diddy camp by native carrier. However, it did not take long for one of the Zeros circling high over Lae to spot something and the Japanese soon responded in force.33 On 1 May a strong enemy patrol moved up from Lae to Yalu where it was delayed by the brave native man Alisipi, who had also sent other men to warn the NGVR posts at Munum and Ngasawapum of the patrol. A telephone at Ngasawapum was used to warn Diddy camp and at 1030 another call from Corporal Frank Purcell at the observation post near Munum village reported 300 enemy troops moving up the road from Yalu. Half an hour later he was back on the line to report that the Japanese patrol was now only 200 metres away. ‘I’m off, they’re here,’ he said and hung up.34 As he finished his report two shots were fired at Purcell but he managed to get away.

In the late afternoon the supply truck was returning to Diddy camp from Nadzab with a load of supplies. As the truck reached the Ngasawapum turnoff the driver could see a native up ahead waving his cloth wrap in obvious warning. It was a brave thing to do as Japanese troops were lying in ambush in the dense head-high kunai grass between him and the truck. The truck was hastily abandoned as the occupants went bush. The Japanese removed the stores from the truck and burned them before some got aboard, turned the truck around and headed back towards Nadzab.35

Further along the road, 4 kilometres east of Nadzab, a party of four men were also making their way towards Diddy camp. Unaware that the truck had been captured, the two leading men, Signaller Len McBarron and Sergeant Robert Mayne, let it drive up to them. They were captured and never seen again. Riflemen John Rouse and George Cochrane were further back but when they came around a corner on the Markham Road they were confronted by a Japanese soldier. Rouse fired his rifle and the two got away into the scrub.36

Back at Diddy camp, after receiving the warning from Frank Purcell at Munum, Captain Lyon told Bob Emery, ‘Now, I want you to take a small party down to Ngasawapum and see what they’re up to.’ Emery got halfway to Ngasawapum when he saw a native policeman approach along the track. ‘The Japs, big Japanese patrol just captured the truck,’ he told Emery. Emery and Bill Murtagh continued down to the road and, as night fell, followed the path of the captured truck until they found it bogged up to its axles and abandoned. ‘It’s like going to a football match,’ Emery observed, ‘and then they all go home.’37

Meanwhile, on the day before the truck incident, a strong patrol had left Diddy camp for Lae. It was led by Captain Roy Howard, accompanied by Lieutenants Colin Anthony and Bob Phillips with fourteen native carriers and a native policeman. The patrol reached Munum at midday and then spent the first night at Tuckey’s camp which was located past Yalu village. On reaching Lae the men set up an observation post about 2 kilometres from Lae airfield. Early on the morning of 3 May the observers watched as two flights, each of seven bombers, passed over Lae heading south escorted by thirteen fighters from Lae. Soon thereafter the patrol was fired on by a stronger Japanese patrol which was only some 75 metres away. Five men, including Howard and Phillips, managed to flee into thick scrub, though they had to abandon their equipment.38 The men had been surprised in a tent on the outskirts of Jacobsen’s Plantation while drying their clothes in the sun and they turned up at Diddy camp the next day, ‘bare-footed and in their pyjamas’.39

On 21 May Bob Emery, his younger brother John, Lieutenant Keith Noblett, Frank Anderson, John Clark and James Savage went back to the observation post above Whittaker’s Plantation, on the high ground across the road from Heath’s.40 ‘When we did get there everything was exactly as it had been left,’ Bob Emery later said. The lookout was up a hill behind the camp and from there one could look directly down onto the house at Heath’s Plantation where the Japanese had an outpost and field gun.41 At dawn the next day, John Emery took Anderson up to the post, but soon after heading back he heard a rifle shot so returned to investigate. As he got close he could hear Japanese chatter so he once again headed back down to the camp. ‘The Japs are up there and they’ve got Frank Anderson and they’re coming over the hill now,’ he told his brother. Bob Emery headed up the hill to look for Anderson but soon realised the Japanese were indeed on the way down using a spotlight to light the way. Emery got down on the ground and shot the leading enemy soldier at 50 metres. ‘This poor old Jap folded up, and another bloke stepped over him,’ Emery said. But by firing in the dark, Emery had betrayed his position and he soon attracted considerable fire. ‘God, spare me days,’ he thought, ‘the whole bloody army’s shooting at me,’ and he headed off. There was more shooting, some shelling from the field gun at Heath’s and some aircraft circled overhead but the NGVR patrol managed to get out. Frank Anderson was likely ambushed and shot dead by that first rifle shot and his body was never found.42

With the Japanese now awake to the Australian presence and Japanese air patrols now keeping a close eye on the river and the area around Diddy camp, Captain Lyon pulled most of his men back across to the south bank of the Markham.43

•

With the observation posts on the outskirts of Lae now compromised, an alternative site was set up in the ranges south of the Markham River, about 150 metres above Markham Point. Known as the Tojo observation post, any movement on Lae airfield could be observed through a powerful telescope. As Stan Burton noted, it was not so difficult to find good observation posts but the concern was ensuring that the smoke the generator produced when charging the radio batteries was not apparent from the air.44 Tojo was staffed by two RAAF signallers who radioed details of any air movements to Port Moresby. However, as Bernie ‘Buster’ Mills observed, ‘the results of our bombing did little to prevent the Zeros taking off as they only needed a short runway’.45

Lae had been garrisoned since March by the 82nd Naval Garrison and since 2 April the 2nd Maizuru Special Naval Landing Party had augmented the garrison.46 By 21 May it was estimated that there were 600 to 800 Japanese personnel in Lae with another 150 to 200 at Salamaua. It seemed clear that the Japanese would soon contest the NGVR presence in the Lae area but Australian reinforcements were also on the way.