‘More than half a hundred craft of all descriptions moved on, relentlessly, majestically, in line of four abreast … What one of us will ever forget that sight,’ Private John Holmes from the 2/13th Battalion wrote. Holmes had boarded the APD Gilmer at Milne Bay, climbing up a scramble net from an LCVP, helped by the strong arms of the American sailors. The empty LCVPs were then winched aboard. ‘We trundled aboard somewhat in the fashion of overloaded donkeys,’ Holmes wrote. Once aboard, the Australians then gave their rations to the American cooks, one of whom said, ‘I wouldn’t cook that stuff. We got grub that’ll do you.’ ‘I still recall vividly the roast beef and tomato ketchup,’ Holmes wrote. Gilmer left Milne Bay at 0700 on 3 September. ‘Clapping on 22 of her 27 knots [41 km/h] the Gilmer steamed down the bay,’ Holmes wrote.1 Captain Ken Esau from the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion had a more stifling experience aboard one of the landing craft: ‘That night, cramped in the congested hull of the LCI, where miracles of compression provide a bunk for every man, but not enough room for a dog to bark or air to bark with, the fleet makes for its staging point at Buna. All night sweat rolls from you.’2

The men disembarked at Buna for a break and then reembarked in the afternoon. It was only at this stage that they were told that they would be landing on the beaches east of Lae (see Map 9). Four APDs, Gilmer, Humpreys, Brooks and Sands carrying sixteen LCVP landing craft, made up the first echelon of the Lae landing. Gilmer and Brooks would land two 2/13th Battalion assault companies under Captain Paul Deschamps and Captain Edwin Handley at Yellow Beach. Two other assault companies, Captain Bill Angus’s company from the 2/15th and Captain Philip Pike’s company from the 2/17th Battalion, were aboard Sands and Humpreys destined for Red Beach.

The second echelon, ultimately comprising twenty LCIs in three sections, left Milne Bay first, at 1300 on 2 September, heading for Buna at 22 kilometres per hour, arriving there at 0800 on 3 September then departing for Lae at 2000 that night.3 The second wave for Yellow Beach, carrying the other two 2/13th Battalion infantry companies, came from this echelon as did the second wave at Red Beach which comprised four infantry companies, two each from the 2/15th and 2/17th Battalions. The third wave at Red Beach, four LCIs carrying more 20th Brigade units including brigade headquarters, also came from this second echelon.4

The third echelon was made up of eighteen LCTs spread over three sections plus a section of ten LCMs and another of 40 LCVPs. This echelon, which carried a battalion from the 532nd EBSR and its equipment, left Morobe two hours after dark on 3 September. The ten LCMs and ten of the LCVPs were allocated to 9th Division for beach-to-beach ferrying. Echelons 4, 5 and 6 travelled from Milne Bay via Buna with a total of twelve LSTs and twelve LCTs. Fortunately, the sea conditions were favourable as the LCTs could only proceed at half speed in heavy seas. All six echelons would land on D-Day, 4 September. Another nine echelons were scheduled to land up until D-Day+13, that being 17 September.5

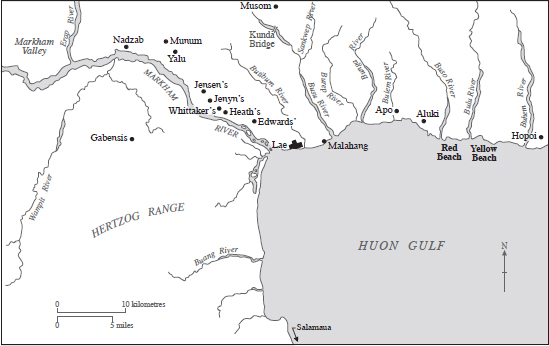

Map 9: Lae area of operations, September 1943

•

As the echelons of the invasion convoy assembled, the ABC journalist Peter Hemery watched. ‘From every point of the compass ships were converging on us mirrored in the glassy waters,’ he observed, ‘a convoy of staggering size for these waters.’6 The waters remained smooth as the convoy crept along the coast past Salamaua and Lae in the dark of night. There were three separate routes to the landing beaches, all converging off the coast at the landing area. Only once the convoy was on the final leg to the landing beaches were most of the men told that Lae was to be the ultimate objective.7

There were a number of war correspondents accompanying the convoy. Bill Carty was one, working as a cameraman with the Australian Department of Information. Carty’s first job in New Guinea had been at Buna where he had met General Wootten. Wootten had told him to ‘go wherever you like, but keep your bloody head down’. Carty would follow the same approach at Lae despite being told to stay on the ship rather than land with the troops. ‘I dismissed it as a ridiculous order,’ he later wrote.8

The first landing craft would hit the beach at 0630 on 4 September, 18 minutes after sunrise. The landing force had wanted to go in at dawn, around 0515, but as the beach was backed by low-lying swampy jungle with no prominent features, 0630 was considered the earliest time that the beach could be identified with any certainty. At both Red and Yellow Beach there was a small coconut grove at the beach to aid identification and these clumps of coconut palms and a river bend were the main features used to identify the beaches. This job was given to the headquarters ship USS Conyngham. Identification took place at 0550, at which point the APDs lowered the landing craft carrying the first wave.9

•

On one of the two APDs off Yellow Beach, the 2/13th Battalion infantrymen waited to be called onto deck to board the landing craft. ‘Faces looked strained in the dull blue light of the “black out” lamps,’ Patrick Bourke wrote, ‘and the occasional snatches of laughter that arose from several quietly conversing groups were just a few notes too high pitched.’ The two APDs lowered four LCVPs each and then the men boarded. ‘We climbed carefully down the swaying net ladders,’ Bourke continued, ‘carefully because the weight and awkwardness of our gear made us clumsy, where a false step would mean drowning or being crushed between the tossing barge and the mother ship.’10 ‘Away the landing force!’ shouted the voice from the loudspeaker as the shore bombardment commenced.11

Five destroyers provided a preliminary bombardment for six minutes from H-11 (0619) by which time the first landing craft were 1100 metres from the beach.12 ‘Your ears soon hear the rolling thunder of a naval bombardment, a pleasing sound when it’s yours,’ Ken Esau wrote.13 Peter Hemery watched as ‘The slowly clearing darkness split with light as flame stabbed from the warship’s guns.’14 ‘We could see a brilliant flash from their guns and the destroyers seemed to jump with the recoil,’ Harry Wells observed.15

From his guard post at the anti-aircraft position overlooking Lae airfield, Kiichi Wada could hear the sound and see the flashes from the naval bombardment out in the Huon Gulf. ‘Suddenly, there was a booming sound from the sea,’ Wada wrote, ‘and in a split second, I sighted red and yellow tracers come flying on a half moon ballistic arc.’ ‘Where would the huge fleet land?’ he pondered. ‘Aren’t they, in fact, landing right here in Lae?’ The Lae garrison had been given orders to fight to the death and Wada thought, ‘If I must die, I will fight with courage and die like an imperial navy man without shame.’16

Aboard the eight landing craft heading for Yellow Beach were the two assault companies from Lieutenant Colonel George Colvin’s 2/13th Battalion. ‘What Japanese enemy lurks in that tall proud jungle?’ John Holmes pondered. Holmes felt the relief, determination, fear, amazement and wonder ‘at this strange mechanised mission intruding upon the beauty of the tropic dawn.’ ‘We squatted down, our heads beneath the gunwhale, gazing at the outline of our bayonets against the pale blue sky.’ Some of the men then raised their heads and watched as the bombardment burst along the shoreline. Then ‘the naval guns fell silent, the barges revved and shot for the shore’. At the same time, the machine gunners on the barges opened fire at the shoreline. The landing craft were unarmoured but fortunately there was no return fire from ashore. At 0633 the ramps dropped and the platoon commanders and Owen gunners scrambled for the jungle. Ten minutes later the first wave of the 2/13th had reached its objective.17

The second wave then approached the beach in the larger LCIs. ‘Bayonets were fixed and actions cocked,’ Patrick Bourke noted. The first LCI beached correctly but the second hit a reef 20 metres from shore and the men had to wade ashore in water up to their chests. The LCTs of the third wave came in an hour later and the first metal strips were laid out to ensure that the disembarking vehicles did not bog down in the heavy black sand. ‘Men loaded with gear scurried back and forth across the beach, and there was a continuous babel of orders,’ Bourke observed.18 There was no enemy resistance at Yellow Beach after some 30 Japanese defenders abandoned their strongpoint, leaving behind weapons and equipment at the former Bulu Plantation manager’s house. ‘They had departed in some haste,’ Bourke wrote, ‘there were signs that most of the garrison had been in bed when the assault began … there were gaping rents where shells and HMG [heavy machine-gun] bullets had torn through the walls.’19

By mid-afternoon the 2/13th had extended the Yellow Beach perimeter 3000 metres inland, 2000 metres east and the same distance west from the landing beach. ‘The swamps had proved narrow, if nasty; the scrub had been neither as dense nor as tall as thought,’ Bourke wrote. ‘Two o’clock and all’s well.’20 ‘As far as we’re concerned everything went according to plan,’ Les Clothier noted.21 The Australians went looking for a fight, with two companies moving east along the track towards Hopoi mission station where opposition was expected.

The first wave for Red Beach was also carried in two APDs, each of which lowered four LCVPs holding one of the assault companies. From the ‘Tojo’ observation post in the Buang Ranges south of the Markham River, Captain Vic Tuckerman watched the ‘landing craft spread out in fan like formation’.22 As the landing craft approached the beaches, Harry Wells watched as ‘their machine guns chattered away spraying the beachhead with a continuous stream of tracer bullets’.23 The gunfire was only going one way and both companies had landed unopposed by 0615.

The three battalions of Brigadier Victor Windeyer’s 20th Brigade plus the attached 2/23rd Battalion, which was to act as brigade reserve, also landed without opposition. ‘As each wave discharged its load and drew offshore to reassemble, another wave grounded in the shallows,’ Peter Hemery observed.24 General Wootten had specified that the brigade commander had to be ashore early and Windeyer landed 15 minutes after the first wave. ‘I always felt out of touch, impotent and useless until I was ashore,’ Windeyer noted. ‘Once ashore I hoped I could be useful.’25 Although the landing had been unopposed on the ground, danger lurked above.

•

On the day before the landing, 21 Allied bombers had struck Lae airfield but, despite the damage, six Oscar fighters and three Sonia reconnaissance aircraft had managed to land there late in the afternoon, probably intending to carry out further reconnaissance of the concentration of landing craft at Morobe the next day. The three Sonias were from the 83rd Independent Air Chutai which had been based at Wewak and Madang since April 1943. The unit’s Sonia aircraft, often mistaken for Val dive bombers due to their fixed undercarriage, had been involved in operations around Salamaua and at Nassau Bay from May to July 1943. By the end of July only five of the Sonias were still operable.26

On 2 August 1943 one of the remaining Sonias had been involved in a mission to bring the 18th Army commander, Lieutenant General Hatazo Adachi, from Alexishafen to Lae, escorted by nine Oscar fighters. However, the ten aircraft ran into an American air raid over Lae and became engaged with Lightning fighters. While the Oscars took on the Lightnings the solitary Sonia dropped down low and headed for Tuluvu on the western tip of New Britain, landing safely with Adachi. At 18th Army headquarters back in Wewak, Lieutenant General Kane Yoshihara and the other staff officers ‘passed an anxious night, but fortunately next morning … there was a report that he had made a forced landing, so we were greatly relieved’. Adachi flew on to Salamaua on 3 August before he was returned to Madang in the trusty Sonia three days later.27

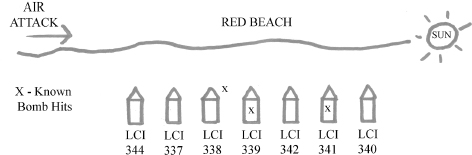

Now on the morning of 4 September, ‘like a peal of thunder in a clear sky’, word had come through that an amphibious landing had taken place east of Lae and the three Sonias and six escorting Oscars were hurriedly readied for action and took to the air at around 0700.28 Kiichi Wada watched as the planes flew past his anti-aircraft position east of the airfield. ‘Hei, the Rising Sun, our planes!’ he wrote.29 Only minutes after taking off, the aircraft were over Red Beach flying east along the coast into the rising sun. At 0704, half an hour after the initial landing, the aircraft came in low over Red Beach and, before any Allied fighters could intervene, the six Oscars strafed the landing craft followed by the three Sonias on a bombing run (see Map 10).30 ‘Suddenly the dull roar of barge engines was drowned by the staccato crack of ack ack,’ Peter Hemery observed, ‘as warships opened up on eight enemy bombers which had slid over mountain tops in background to bomb and strafe the tight formation of barges.’31 ‘Japanese bombers screamed down’, Harry Wells wrote, ‘Like large silver birds they sped onward dropping their eggs of death.’32

Troops from the 2/23rd Battalion, who were on seven LCIs about 30 metres apart approaching the beach, spotted the six low-flying Oscar fighters heading straight for them, the puffs of smoke along the wings signifying their intent. ‘Cannon shells are hitting the bridge,’ Ken Esau wrote, ‘but the strafing is just too high to hit the packed mass of men on the deck.’ The fighters made one pass but behind them were the three bomb-loaded Sonias. One bomb crashed through the main deck of Ensign James Tidball’s LCI 339 forward of the pilot house and the ship caught fire, listed to port and quickly began to take on water. Ken Esau watched from LCI 338, worried that it was ‘sinking, out of control, and may ram you as she yaws wildly’. The stricken landing craft was run ashore and abandoned by the crew, ten of whom had been wounded. Lieutenant Fay Begor later died.33 ‘There were 3 bombers with the Zeros & it was them that done the bombing,’ Les Clothier noted.34

Another bomb narrowly missed LCI 341, exploding near the bottom of the ship and blowing a large hole amidships on the port side, flooding two compartments. A list to port was corrected and the LCI was run ashore where it was salvaged a month later. The commander, Lieutenant Robert Rolf, remained with the ship and was killed during another air attack two days later.35 Nine men from the 2/23rd Battalion were killed including the commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Reg Wall, while 45 more were wounded.36 The LCIs had restricted exits from troop holds and this contributed to the heavy casualties. Upon landing, Major Eric McRae took over command of the battalion. Bill Carty watched the air attack from LCI 340, the LCI at the eastern end of the line and next to LCI 341. ‘Out of nowhere, a Japanese plane headed directly towards the beach,’ he wrote, ‘the plane dropped its bomb just before it skimmed over the top of my ship.’37 ‘The force of the bombs of our friendly planes astounded me,’ Kiichi Wada wrote. ‘I saw with my own eyes the immense power of the black gunpowder … Unlike the enemy bombs, it sounded harder and the blast more powerful … The smoke was black.’38

Allan Dawes was another war correspondent at the landing and was on one of the bombed LCIs: ‘I saw in the haze of the dawn the flash of the warships’ guns as salvo rolled on salvo and a bombardment of upwards of a thousand rounds softened whatever resistance might be offering; saw the first waves of light landing craft go into the coconut grove which was the agreed pointer to the landing beach; saw Japanese aircraft flash down, bomb, strafe, and kill.’ Dawes was lucky to survive. ‘Swinging by a stanchion, burning hot, over the huddled body of an Australian soldier whose clenched hand still held the Bren [light machine gun] he was taking ashore when he was struck down by the same blast which skittled a case of mortar bombs, I plunged into the hold of a still-smoking landing craft to retreat hastily before the stench of smoke and high explosive,’ he wrote.39

Harold Guard, an American war correspondent, was aboard LST 458 heading for Red Beach. During the trip to Lae the steering gear had broken down and Guard, who had once served on a submarine with the same steering mechanism, was able to help get it fixed. ‘Good Lord!’ the engineering officer exclaimed, ‘a bloody correspondent has put the steering gear right!’ As the LST approached the shore, Guard could ‘see the wire meshed landing strips that had been laid down’ to help any vehicles to get off the beach. He could also see the beached LCI 339 was still on fire and LST 458 beached alongside it to help douse it with fire hoses.40 Petty Officer Fay Fielder was a crewman on LST 458. ‘When we got there one was already hit, they strafed it or something and it was burning so our forward damage control guys went over there and they put out the fire,’ he recalled. ‘They secured the engine and they said the ship was abandoned. There was no one on her. So they just left it there beached.’41

Three weeks after this attack, the 83rd Independent Air Chutai was awarded a citation by General Adachi. In that citation the attack by the Sonias at Hopoi (Red Beach) was highlighted alongside the earlier operations around Salamaua and Nassau Bay. ‘It is a deep regret that the majority of their personnel were either killed or wounded during all these operations,’ Adachi added.42

•

Two flights from RAAF No. 4 Squadron with eight Boomerangs and two Wirraways based at Tsili Tsili were supporting the Lae operation. Though obsolete as fighters, both aircraft types were well suited to reconnaissance and observation in support of ground troops. Flying Officer Ron Dickson watched the landing from his Boomerang, circling over the beachhead protecting the small aircraft that were directing the naval gunfire. ‘It was a fantastic sight, seeing this huge fleet of vessels disembarking the troops, supplies and equipment onto the beaches,’ he later wrote.43

Following the landings, the engineers at Red and Yellow Beach quickly got to work clearing the beachhead and constructing roads. By nightfall all objectives had been achieved. The 2/17th Battalion had crossed the Buso River and by 0730 the following morning the 2/7th Field Company had built a single-girder bridge across it. To protect the beachheads from further air attack, a battery from the 2/4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment had landed two detachments at Red Beach and another at Yellow Beach.

The three assault waves had landed 3780 troops while the follow-up echelons brought in another 2400 plus anti-aircraft batteries, vehicles, ammunition and stores. The 1050 men making up the shore battalion of the 532nd EBSR also landed at this time, having moved up the coast from Morobe on their own LCVPs and LCMs plus some navy LCTs. A total of 7800 personnel and 3300 tonnes of equipment and supplies had been landed on D-Day.44 The Japanese command estimated that 15,000 men, almost twice the actual number, had landed. Given the same naval resources, the Japanese probably would have landed that many.45

Unloading of the landing craft required air cover and this could not be guaranteed after 1100, giving only a four and a half hour window for unloading. The unloading parties had all LSTs cleared within 2 hours and 15 minutes and by 1050 all but one of the LSTs from Echelon Four had retracted from Red Beach. LST 452 was hard aground but was finally pulled off an hour later by the tug Sonoma while three destroyers made waves across the beach to help jolt it free.46 Clearing the stores from the beach was the greater challenge and, after the next echelon of LSTs bringing in the 24th Brigade arrived, uncleared stores were still on the beach at daylight. Fortunately the enemy aircraft that came over did not attempt to bomb or strafe the stores or the men and vehicles trying to move them to cover.47

The LCTs, each carrying 120 tonnes of bulk stores, took much longer to unload. Despite a 2 hour and 30-minute limit, and much to the exasperation of the craft commanders, those LCTs that landed at 0800 were not all cleared until 1430, over six hours later. Two LCT echelons had to withdraw with a large proportion of their load still aboard.48

The original plan was for loaded vehicles to drive off the landing craft ramps and then unload at dump areas before reembarking on the next incoming echelon. However, this was not possible due to the number of other vehicles that were using the exit routes, resulting in congestion and confusion. This led to later echelons arriving bulk loaded rather than on vehicles and unloading took much longer.49 Lieutenant Colonel Bertram Searl, the 9th Division quartermaster, was responsible for beach organisation, assisted by the beach master, Second Lieutenant Bruce Campbell from the 532nd EBSR who had set up a loudspeaker system to help keep the beach under control. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin Brockett, the commander of the 532nd, coordinated his shore group and some of the Australians to clear the stores as promptly as possible.50

Allan Dawes watched the build up. ‘The beach … was throbbing with business, like a market place. Bulldozers, caterpillar tractors, and trucks rolled out of the great holds of a long line of ships straight into the work of making roads, laying steel-mesh strips over soft earth, and transporting supplies. Dumps of crates, cases, boxes, drums, and cans mounted,’ he observed.51 The operation was ‘mainly in the hands of the engineers and quartermasters who have been grappling with appalling difficulties and beating them,’ Merv Weston wrote. ‘Routes had been slashed into the jungle with machetes,’ he added, ‘steel netting had been laid along the sandy beach to carry heavy transports, guns had disappeared inland, and huge bulldozers were already pushing earth to and fro by the ton.’52

As was the case during the rehearsal landings, vehicles backed up on Red Beach because there was only the one track leading inland through the swampy ground behind the beach. This was somewhat alleviated by sending all vehicles and artillery except jeeps down the beach and up the bed of the Buso River in order to clear the beach. This was helped by the firmness of the beach, which could be traversed without wire mesh being laid down. Any wire mesh that had been put in place proved a hindrance as the ends of each sheet could not be anchored and tended to turn up. It was also useless on the swampy ground behind the beach and was therefore discarded in favour of using logs to form corduroy roads.53

The routes from the beach to the supply dumps were the first to be corduroyed. From Apo fishing village onward the beach narrowed, though it could take jeeps despite the numerous streams. The Burep River had a firm base and, with a limited catchment area, did not rise appreciably when it rained so was not a major barrier to supply. The gravelly bed of the river was therefore used as a supply route for vehicles while LCVPs were used to bring the supplies forward from Red Beach to the west bank of the Burep.54

Having spent the day carrying equipment and supplies from the beach to dumps inland, it was soon obvious that too much equipment had been brought in and this would hinder any rapid advance. As Brigadier Windeyer later noted, ‘methods and technique for loading and unloading landing craft were not fully developed until later, when for Borneo a very high degree of efficiency was attained in this art throughout 9 Div, and MLOs [Military Landing Officers] became very skilled’.55

•

Air attacks against Japanese airbases had been arranged for the morning of D-Day. At 0745 thirteen RAAF bombers hit Gasmata, at 0900 24 Liberators bombed Lae and at 0930 nine Mitchells attacked Cape Gloucester. However, the main Japanese airbase at Rabaul was not heavily attacked. At 1317 the US destroyer Reid, acting in an early warning role off Cape Cretin to the east of the landing force, picked up three clusters of enemy aircraft on its radar. They were 126 kilometres away approaching from Rabaul. Captain Ball, the fighter controller aboard Reid, knew that there was one US fighter squadron escorting landing craft back to Buna and another over the beachhead at Lae but did not know exactly where the American fighters were. Once a minute Ball sent out the grid reference of the incoming enemy aircraft across the airwaves, knowing that each pilot was on his frequency and had a grid map in his cockpit. Ball then watched his radar scope, knowing the aircraft would soon reach the isolated Reid. He then went out on the deck and counted around 60 Japanese aircraft pass by heading for Morobe. ‘That was a nasty moment for us,’ Ball noted.56

The attacking force of 81 aircraft from Rabaul was made up of twelve Betty bombers, eight Val carrier bombers and a mixed formation of 61 Zero fighters.57 Captain Ball was able to guide 40 Lightnings and 20 Thunderbolts into the fray with contact made in the vicinity of Reid. Three Val dive bombers bombed Reid without success while the remaining enemy planes headed for Morobe.58

At 1420 that afternoon the six LSTs from the 6th Echelon with the Australian 2/4th Independent Company and 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion aboard were about 33 kilometres east of Morobe and heading north towards Lae in two columns. Many of the commandos had served on Timor where they had fought with guile and success in a harsh and isolated environment. Cooped up in a landing craft they waited anxiously to reach the landing beaches east of Lae. Their anxiety proved well founded as the Japanese aircraft from Rabaul came into sight.59

At 1355 observers aboard LST 473 sighted eighteen enemy aircraft, a mix of bombers with escorting fighters. Two minutes later the landing craft was attacked by at least four Val dive bombers from the south-east. Men from the 2nd Machine Gun Battalion watching from the nearby LST 471 spotted four Vals ‘very high and right in the sun’ dive down on LST 473 ‘with a shrill whine’. The Vals flattened out at about 100 metres above the water and released their deadly load. ‘The bombs are falling,’ the men observed, ‘little black ones from each ship as it flattens out.’ They saw four bombs strike LST 473 which was astern of LST 471. ‘Poor blighters,’ the watchers thought, ‘wonder what their casualties are?’60

LST 473 sustained two direct hits and two near-misses. The first bomb destroyed the starboard side Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun and four ammunition lockers as well as the pilot house and with it the control of the vessel. Keith Hanisch had been watching four men playing cards on the deck as the stern was lifted out of the water. ‘I can still see the four blokes, cards, money and blanket floating in mid air,’ he later said.61 The second bomb penetrated three decks and destroyed both drive shafts. Fortunately, as Bob Phillips observed, the bomb did not explode. Fire broke out but was soon brought under control by the well-drilled crew. Meanwhile, with power to the ammunition hoists knocked out, the commandos were helping to pass shells up to the anti-aircraft guns. One of the commandos, Brian Jaggar, had even taken the place of a wounded American gunner and was helping to fight off the attacking aircraft.62

During this first attack, the LST 473 helmsman, Seaman Frederick Erickson, was blown clear and Seaman Johnnie Hutchins, though also badly wounded in the blast, took over the helm. Then, as the dive bombers left, at least six torpedo bombers attacked from the west about 25 metres above the waves. After the torpedo wakes were sighted Hutchins turned the ship sharply to starboard but it turned very slowly due to the bomb damage. One torpedo passed under the LST and one passed astern. When other shipmates reached the pilot house they found Hutchins dead at the wheel and had to prise it loose from his fingers.63 Hutchins was awarded his country’s highest honour, the Medal of Honor.

Meanwhile LST 471 had been hit in the stern by one of the torpedos that had missed LST 473. ‘A torpedo passed in front of our bridge and went slap bang into the stern of the next LST,’ Bob Phillips observed.64 The LST had been targeted by two torpedo planes at mast height, both of whom were shot down but not before they had released their torpedoes about 1000 metres out. ‘A torpedo seems to float down to the water and hits with a splash,’ an observer noted. The first torpedo passed the bow but the second struck the stern of the LST and, for those aboard, ‘the LST lurched violently, throwing everyone off their feet’. ‘Wounded are now staggering up from the after hatchways, covered in blood,’ one of the men observed. When rescuers reached the stern, they found ‘a mass of twisted, jagged steel plates, strewn around with most shockingly mutilated bodies and human remains’.65

Jim Rae was one of the commandos on board, locked into a compartment down below behind watertight doors and bulkheads. ‘We were being tossed about like rubber balls. Then it was still,’ he later said. ‘All I could see was water down below and sky up above—nothing in between … The back part of the ship was gone.’ Rae was one of only five commandos on the ship still physically able to carry on.66 Ralph Coyne was another one of the survivors. ‘Rising to my feet, I was confronted by horror,’ he wrote. ‘Tiers of bunks collapsed on one another. All men on their bunks were dead.’ Once he made his way up to the deck, Coyne saw how ‘The stern of the vessel where we were quartered was turned up like a scorpion’s tail, the stern gun pointing up into the sky.’67 One officer and six men from the landing craft crew were killed but the greater loss was among the 2/4th Independent Company commandos, 34 being killed and seven wounded, ‘a calamitous loss for a small unit’.68

At the time of the attack, six LSTs from the 4th Echelon escorted by four destroyers were also east of Morobe but heading south after the landing.69 Two of these LSTs, LST 454 and LST 458, were ordered to divert from their course to assist the two LSTs damaged by the air attack. Petty Officer Fay Fielder was aboard LST 458 when it reached the damaged LSTs. ‘They were both helpless in the water,’ he said. At 2000, some six hours after the attack, LST 458 came alongside LST 471 and using hawsers they ‘reeled it in and tied it up with cables’ using buckler guards to keep the two vessels from clashing. ‘It would crush them but it kept them enough apart,’ Fielder recalled. Fifteen minutes later LST 458 and LST 471 were secured, and using the engines of LST 458 the two vessels were safely beached at Morobe five hours later. The cables were then cut and the LST 458 retracted to continue its journey south.70

Before LST 458 left Morobe the medical corpsman, accompanied by Fay Fielder, was sent to see if there were any survivors down below the decks of LST 471. Descending a stairway to the tank deck by flashlight, the two men moved through the crew quarters in about half a metre of water. ‘He’s shining the light there and these guys sitting at the table, they must have been eating, all Australians,’ Fielder said. ‘From what I could see some of those guys didn’t have a mark on them. I mean no cuts, no bleeding, they were dead. Concussion killed them I guess … We realised then that the war was going on.’71

Conyngham accompanied the damaged LSTs to Morobe and assisted with medical treatment, later taking on board 40 wounded who were taken to Buna. The four APDs were ordered back to Morobe from Buna and, once they arrived, another 40 wounded men were put aboard Humphreys which returned to Buna. Gilmer acted as an anti-submarine screen at the Morobe harbour entrance while Brooks and Sands were sent to reinforce the escort for Echelon 6, which had continued on to Lae. Meanwhile the cargo on the two damaged LSTs was offloaded onto LST 454 and LST 458 and they returned to Lae with the five LSTs of Echelon 8 the following day.72 During the air attack the Japanese had lost four Zeros and three Bettys with another three Zeros, seven Bettys and five Vals damaged.73

Meanwhile back at Red Beach more enemy aircraft had appeared at 1700, setting fire to an ammunition dump and killing two US shore engineers and wounding twelve. The two stranded LCIs that had been hit in the morning attack also received further damage. Low-level bombing and strafing attacks were stymied by the anti-aircraft guns but high-level bombing took a toll. There were nine air attacks on Red Beach during the first two days of the landing.

At Yellow Beach the Australian infantry appreciated the air cover. ‘All day squadron after squadron of fighters had circled above us,’ one observed, ‘and squadron relieved squadron according to such an accurate timetable that there was scarcely a minute that we were without air cover.’ However, just as the last sixteen Lightning fighters left the area at 1630, four Lily bombers, escorted by Zeros, bombed and strafed the beaches.74

With US air units responsible for attacking the Japanese airfields at Wewak, Lae and at Tuluvu on Cape Gloucester, the RAAF got the job at Gasmata. At 0730 on the morning of 4 September, ten Beaufort bombers from RAAF No. 100 Squadron, backed up by three A-20 Bostons (the Australian name for the A-20 Havoc) from RAAF No. 22 Squadron, bombed the airfield despite heavy anti-aircraft fire. One of the Beauforts, piloted by Flying Officer Tom Allanson, was shot down and the four-man crew were lost. Another Beaufort pilot, Flying Officer John Baker, later wrote, ‘I dodged and weaved all I knew. It was the most thrilling experience of my life.’ Three Bostons returned to Gasmata later in the afternoon and bombed and strafed the airstrip. ‘Strip considered unserviceable,’ the 22 Squadron War Diary noted.75

On the following morning of 5 September the three Bostons returned to Gasmata, knowing how important it was to put the airfield out of action following the previous day’s Japanese air attacks. When the attack went in at around 0600, it was clear some repair work had been carried out but this time the Bostons left the airfield ‘definitely unserviceable’. Nonetheless, just after 0700 ten Beauforts followed up with another attack but they faced unexpectedly heavy Japanese anti-aircraft fire and, as the Beauforts made their bomb run in a shallow dive, five of the aircraft were hit. Flight Lieutenant Roy Woollacott’s aircraft, which led the flight, was one of them, but with his Beaufort in flames he continued the bomb run and dropped his four bombs on the runway. He and his four crewmen were killed as were the crew from two other Beauforts, one of which crashed into the sea and the other into the hills to the north-east. The other two damaged Beauforts made it back to Goodenough Island where one was destroyed on landing, though the crew survived.76

•

Although a direct attack on Lae had been expected by the Japanese at some stage, as Kane Yoshihara noted, ‘for the front line units it was like a peal of thunder in a clear sky’.77 The initial Japanese response was as expected. At 1700 on 4 September orders were issued that ‘The division must defend Lae and Salamaua to the death.’78 Kamesaku Iwata, a naval medic with the 82nd Naval Garrison, wrote that he ‘strangely felt calm thinking that finally I can die for my country’. Iwata had come to Lae in the wake of the loss of the Bismarck Sea convoy where his vessel had been sunk and the survivors left to drift at the mercy of the strafing Allied aircraft. ‘It will be different this time,’ he wrote. ‘Being killed while killing the enemy is my long cherished ambition.’79

It was specified that ‘Commanders in the Lae area will combine and lead army and navy units, and must defend Lae with all their strength.’ That night further orders came from 18th Army headquarters specifying that the 51st Division must concentrate its forces at Lae and take over command of the naval forces for the defence of Lae. Based on these orders General Nakano decided that Salamaua would not be defended to the death and the units there would begin the withdrawal to Lae on the following day, 5 September. Engineering and anti-aircraft units would be the first to move.80