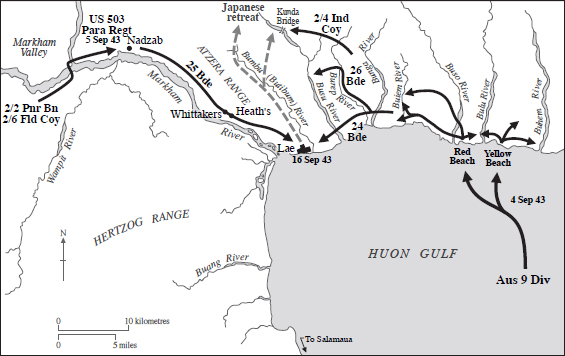

The first plane over Nadzab early on 5 September was able to report that the weather conditions were suitable for the second phase of Operation Postern to proceed (see Map 11).1 Once given the green light for Z-Day, the three battalions of the 503rd Parachute Regiment embarked on the 82 C-47 transports from the 54th Troop Carrier Wing and headed across the Owen Stanley Range to Nadzab. Over Marilinan the aircraft manoeuvred into their six-plane groupings for the parachute drop.

At one minute before H-Hour three squadrons of Mitchells bombed and strafed the wooded areas adjacent to the drop zones. The Mitchells were followed by three flights of Havocs which laid down a smokescreen in front of those wooded areas. Other air support came 30 minutes after the H-Hour drop when Liberators and Flying Fortresses dropped bombs on Gabmatzung, Gabsonkek and the Markham Valley road to Lae. Another squadron of Mitchells provided direct support to the paratroopers on the ground, with one-third of the squadron on call for 90 minutes at a time. There was also a squadron of Airacobra fighters on call from Tsili Tsili and they carried out armed reconnaissance flights over the Lae road looking for any Japanese troops moving towards Nadzab.

Map 11: Lae operations, September 1943

•

On the ground, a company from the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) patrolled the south side of the Markham River upstream from the Watut River junction to prevent any crossings by local natives until the operation was well underway. Once the paratroops had dropped, the PIB company would cross the Markham and patrol the north bank from the Erap River junction to Chivasing and into the Markham Valley, looking out for any Japanese movement west of Nadzab. Another PIB patrol at the former Diddy camp would detect any enemy moves from the north. Further downstream the infantrymen of the 24th Battalion kept a close eye on the Japanese troops holding Markham Point.2

Both General MacArthur and Kenney watched the landing from Flying Fortresses circling above Nadzab. Kenney had told MacArthur he wanted to be there because ‘they were my kids’. ‘You’re right, George,’ MacArthur replied, ‘we’ll both go. They’re my kids, too.’3 General George Vasey, who had seen German paratroops in action over Crete in 1941, also watched the drop from above. ‘I wanted to see [paratroops] land from the top rather than the bottom as in Crete,’ he wrote to his wife.4

Lieutenant Colonel John ‘Smiling Jack’ Tolson, the commander of the US 3/503rd Battalion, would make the first combat jump in the Pacific. He could see the airfield below but, as he looked up for the green light to jump, it didn’t flash on; the excited pilot and navigator had failed to press the button. ‘So I hesitated for a few moments,’ Tolson later recalled, ‘then saw we were over the middle of the field, and I jumped.’ The delay meant that quite a number of Tolson’s men ended up in the trees at the end of the drop zone.5 Three columns of C-47s with escorting fighters above and on either side deposited their troops over the three landing grounds in four and half minutes. Three men were killed in the jump, two of whom were ‘streamers’ whose chutes failed to open, plus one man who got hung up in a tree before falling about 20 metres to his death.6 One of the 82 transports did not drop any men after the door blew out as it was being removed, leaving it hanging from the side of the plane, thus endangering the life of any jumper.7

There were seven war correspondents aboard the troop carriers that morning and Merv Weston was one of them. ‘It was all over so quickly,’ he wrote, ‘that all one was left with was of a vision of parachutes billowing briefly, and then a big concentration on the ground that looked like so many sheep.’8 RAAF Boomerang pilot Alex Miller-Randle watched the drop from well above: ‘I saw below me dozens of DC3s [C-47s] and the parachutists tumbling from open doors and floating down like little mushrooms.’9 Although all drops were successful, the two to three metre high kunai grass hampered the assembly of the battalions. Nonetheless, two hours after the jump all units were in position and work on clearing the airfield had commenced. General Kenney was suitably impressed by the near faultless parachute drop. In a letter to his superior, General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold, Kenney wrote that ‘the operation really was a magnificent spectacle. I truly don’t believe that another air force in the world could have put this over as perfectly as the 5th Air Force did.’10

An hour after the initial 503rd jump, Lieutenant Johnnie Pearson’s gun detachment successfully jumped with the two light 25-pounder guns.11 Lieutenant Alan Clayton took part even though he had not made a training jump, having replaced another officer who had broken his ankle in training. David Wilson had also fractured his ankle during training but kept quiet about it and made the jump.12 Norm Anderson remembered how the men were shouting out to each other as they descended, joking about the experience until the final 6 metres or so when the ground ‘came rushing up at you’. Like most of the gunners, Anderson ‘landed pretty hard’, but all of them got down safely though a crosswind scattered them along the kunai-covered Nadzab airstrip. They had all jumped on the first pass across the strip and the equipment came down on the second and third passes. The gun crews managed to get the first gun into action soon afterwards although its support was not immediately required. However, the parachute load containing the buffer and recuperator for the second gun was not found in the head-high kunai grass until three days later. ‘It wasn’t fun trying to find the parts,’ Norm Anderson recalled.13 There was no Japanese resistance to the landing and Pearson’s gunners didn’t get to fire a shot in anger on this occasion.

Lieutenant General Kane Yoshihara, the Chief of Staff of the Japanese 18th Army, later wrote, ‘While the Lae units were keeping at bay the tiger at the front gate, the wolf had appeared at the back gate.’14 What the Japanese didn’t know, but soon came to realise, was that General MacArthur had ordered that the paratroopers were not to be employed on infantry tasks and would therefore not be advancing into Lae.

•

After flying into Tsili Tsili on 1 September, the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion and 2/6th Field Company, plus medical and signals detachments, trekked to the south bank of the Markham River on foot. Using concealed routes east of the Watut River, the men took two days to reach Kirkland’s camp about 10 kilometres from Nadzab. The pioneers made the strenuous journey helped by 700 native carriers and with 35-kilogram loads on their own backs. ‘A lengthy column of troops and carriers toting stores,’ one of them noted. A separate engineer party in twenty folding boats with outboard motors moved down the Watut and Markham rivers to Kirkland’s with instructions not to reach the Watut–Markham junction before 1800 on Z-1. The boats, each of which could carry eight men, were then brought down the Markham by night to cross the river once the parachute drop began at H-Hour. Two boats were lost and one sapper drowned during this difficult move which was made using oars rather than the unreliable motors. The boats were to carry the 2/2nd Pioneers and later the native carriers across the Markham to Nadzab.15

The sapper who had drowned after his boat got snagged in the Markham and capsized was Lance Corporal Harry Fagan. Fagan was a shearer from Coonamble in western New South Wales who had enlisted with his twin brother Maurie early in the war. One of his mates in the 2/6th Field Company was Bert Beros, who had penned the iconic ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’ poem during the Kokoda campaign. Beros also penned a poem in memory of his mate. ‘We left you sleeping, Harry, where the Markham waters flow,’ wrote Beros, ‘A sapper cobber whom we’d known so long.’16

The 2/6th Field Company arrived at Kirkland’s on the night of 4–5 September and, once the men saw the parachutes fill the skies the next morning, the sappers began crossing the Markham. The river was divided into four streams, the first three of which were fordable but the fourth, the main river channel, requiring an improvised footbridge. The sappers used eight of the motorised folding boats, anchoring seven of them across the river, joined by timber cut from saplings along the river bank. The eighth boat was used to ferry troops across the gap to the bridge until more boats arrived to complete the bridge. Two upstream anchors were used on each boat with a breast line connected to the middle boats from each bank. By 1230 the pioneers were crossing the 64-metre-wide fast running river. To get the carriers across, a chain of rubber boats was suspended from a 64-millimetre steel cable that had been strung across the river. The system, which required an anchored A-frame and considerable cable and rope management, was installed within 30 minutes. Each rubber boat carried two or three men plus stores across the river.17

As soon as they saw the paratroops drop, the 2/2nd Pioneers moved off in extended order over the sandbanks to the main channel of the Markham. The pioneers were all across the Markham by 1400 and then made their way to Nadzab to help clear the airstrip. Rather than wait for mowers to be flown in, the pioneers burned the grass off the airstrip and cleared away any rubbish. The burning did not go well as considerable stores and equipment also went up in smoke. More seriously, with no layer of grass to bind the soil once the aircraft began landing, the baked unbound surface subsequently broke up, and within a week the landing ground had to be closed for repair.18

The minimum dimensions for the transport airstrip at Nadzab were 840 metres long and 27 metres wide with a 62-metre-wide cleared area overall. The airstrip would later need to be expanded to the more desirable 1200 metre length and 45 metre width with a 110-metre-wide cleared area. Although a gradient of two degrees across the runway would normally suffice, in tropical conditions it needed to be three degrees to disperse any rainfall. A drainage system to cope with the water from the airstrip also needed to be constructed, in this case using ditches running either side of the strip. Two landing strips were to be constructed as soon as possible, with unloading facilities for 24 aircraft.19

The first aircraft to land at Nadzab was a Piper Cub at 0940 on 6 September with Lieutenant Colonel Woodbury on board ready to get his airborne engineers to work. At 1050 the first of 32 C-47 transport aircraft landed, all of them coming from Tsili Tsili. The first two C-47s brought in the engineering headquarters for 7th Division along with loading ramps. The next seven planes carried equipment from Woodbury’s 871st Airborne Engineer Battalion including a D4 bulldozer which had been dismantled and spread over three planeloads. The tenth plane brought in US airfield control personnel and the next 17 aircraft brought in the US 707th Airborne Machine Gun battery for airfield defence.20

Other aircraft acted a ferry service for 7th Division troops from Port Moresby to Tsili Tsili and then onwards to Nadzab on the following day, 7 September, when 66 planeloads would land at Nadzab. General Vasey’s 7th Division headquarters and signallers landed first, followed by the first infantry from the 2/25th Battalion and the 2/4th Field Ambulance. Next to land was the 54th Battery of the 2/4th Field Regiment with four standard 25-pounder field guns. The 7th Division troops carried their own ammunition plus three days of hard rations and two days emergency dehydrated rations. One field ration per man was also carried on the plane plus two extra bandoliers of small-arms ammunition which were to be dropped off after disembarking.21

•

Captain Reg Seddon had one of the toughest jobs in Port Moresby, arranging a marshalling area within range of all 7th Division units but with sufficient space to disperse 100 trucks. It also had to be in reasonable proximity to the three major Port Moresby airfields and have good two-way all-weather road access. Seddon began looking for a suitable site on 30 August and, with vacant space at a premium, he took one and a half days to find one. He chose the area at the southern end of Jackson’s airfield, believing the site ‘was the only one that was eminently suitable’. It was 800 metres from the end of the runway and about 7.5 metres lower.22

On 5 September Seddon organised eleven planeloads for embarkation, all of which flew to Tsili Tsili. On the following day he arranged another 68 planeloads, also to Tsili Tsili. Well before dawn on the morning of 7 September, Seddon had eighteen trucks carrying much of Lieutenant Colonel Tom Cotton’s 2/33rd Battalion ready and waiting at the new dispersal area, scheduled to head to Durand airfield to embark for the trip north across the Owen Stanley Range.23 Jackson’s airfield was also a key base for the USAAF heavy bombing units and the long-range bombers were busy ensuring that the major Japanese base at Rabaul was kept under surveillance and control. At the same time as the Australian troops were gathering for their flights, the USAAF ground crews were preparing heavy bombers for their own flights north.

The morning was cold and Doug Marshall had jumped aboard a truck next to his big mate Ivan ‘Slim’ Whittle, the son of one of Australia’s most highly decorated soldiers of the First World War. ‘Come up here and I’ll keep you warm,’ Whittle had told him. At 0420 Marshall heard the roar of the first of the Liberator bombers taking off, only clearing the trucks by about 30 metres. Sergeant Bill Crooks heard ‘a deep throated blast and roar of aircraft engines’. ‘Christ! He was close,’ one of the other men quipped, ‘I hope we don’t stay here too long.’24

Five minutes later another Liberator, Pride of the Cornhuskers from the US 403rd Bomb Squadron, loaded with four 500-pound bombs and 10,500 litres of fuel, took off. Piloted by Second Lieutenant Howard Wood, the fully laden bomber struggled to gain lift. ‘This plane was much louder,’ Doug Marshall noted.25 The men in the trucks looked anxiously towards the end of the airstrip off to the right where the plane ‘seemed to hang just above the ground’. Then it ‘came crashing through the trees, its engines roaring’ and after the left wing sheared off, the Liberator ‘smashed down like an arrow into the trucks’.26 ‘Everything went white. The sky went white with flame,’ Doug Marshall recalled. Ivan Whittle was killed but ‘as he got hit he just pushed me clear, over the side of the truck’.27

The point of impact was 640 metres from the end of runway with the aircraft wreckage zone scattered forward another 120 metres over a 70-metre width.28 Five trucks had been hit and four of them were on fire. The other, the second truck in line, was blown over onto its side. Private Fred Ellis was in the last of the five trucks hit and saw the Liberator come over a rise. ‘Gee it’s low,’ he said, just before it struck a tree, lost the left wing and crashed into the hillside nearby. The blast from two explosions blew Ellis out of his truck. Firefighting was ineffective and the vehicles could not be approached due to exploding ammunition and had to be allowed to burn themselves out.29

Reg Seddon, who was in the control tent, heard the normal sound of the first aircraft taking off from Jackson’s but soon after heard a tremendous crash and the sound of exploding bombs accompanied by a great ball of fire rising above the marshalling area. He immediately phoned through to request the dispatch of all available ambulances, medical officers and firefighting units to the crash site. He also ordered all trucks still in the Durand dispersal area to move to the nearby Jackson’s dispersal area and used the loudspeaker to call for all able men to help with the injured. Private Harry Davies, Reg Seddon’s batman, was walking from the cookhouse to Seddon’s tent when he heard the crash and explosions. His immediate thought was that it was an air raid and he went to ground. Then he saw the flames and heard the screams.30

Captain Eric Marshall was second-in-command of A Company. The company was in trucks moving slowly in the dark along the top of a rise at the end of Jackson’s Strip. ‘The whole scene was vividly lit by an intense light, a wave of heat hit the top of the ridge, plane wreckage was hurtled up over our vehicles and everyone rushed for the leeward side of the ridge,’ he later wrote. What seemed to be only minutes later the men jumped back on the trucks and drove on, ‘past what appeared to be a nightmare scene’, Marshall wrote. ‘The fire was still burning fiercely, small-arms rounds were exploding, incendiary bombs were alight.’31

Ray Fewings put his hand up to protect his face. ‘It burned down the side of my face,’ he said. ‘Some were completely alight, desperate, running around and yelling “put me out”.’32 Fred Caldwell saw how, ‘Flaming high-octane fuel sprayed the vehicles, men became blazing torches.’ Ammunition exploded, killing some who tried to rescue others. ‘We did our pitiful best … horribly burnt men pleaded to be shot,’ he recalled.33

Bill Crooks sat on the tailgate of the end truck involved in the accident. A two-year veteran of the war at the age of 17, he was one of the most experienced soldiers in D Company, although still one of the youngest. Crooks was chatting with Frank Smith and Billy Musgrave as the Liberator took off, exhaust sparks and flames obvious as the plane clawed for height off the runway. ‘Christ, it’s going to hit us!’ somebody screamed, ‘Look out! Look out!’34 ‘The trucks were wood lined and open,’ Crooks related, and the men on the right-hand side copped the worst of the blast. The men were all carrying cloth bandoliers of .303 cartridges and a box of grenades was shared between two men. Each also had two mortar bombs, all to be dropped off on landing at Nadzab. ‘The rear bomb fuses stuck out of the men’s pockets,’ Bill Crooks remembered, ‘the men were loaded up with so much ammo.’ The blast flung Crooks out the back of the truck into a tree where he hung by his belt from a branch. He wondered where the heat was coming from and soon realised his bed roll was on fire so used his knife to cut himself free and then joined up with Jimmy Laing. They could smell fumes from the petrol that had soaked into the gravel track and gathered in the culverts like a fire grate. The two men watched the rivulets of flaming petrol running down the hill ‘giving off tremendous heat’.35

Three of the four 500-pound bombs carried by the Liberator had exploded in the crash. With his leg badly damaged, ‘Big’ Jim Condon lay next to the unexploded bomb for some time, unable to move. Bill Crooks, Jimmy Laing and Billy Musgrave found him, seemingly stuck to it. ‘I’m bloody glad you found me,’ he quietly told them, ‘my eyes are sore staring at that great bomb and waiting for it to go off.’ The impact of the crash had knocked the caps off the nose fuses of all four bombs, thus removing the safety blocks. However, the striker head on the fourth bomb had apparently not hit the ground and Captain Vince Berger, a USAAF ordnance officer, was able to remove the nose and tail fuses, thus disarming it.36

Captain John Balfour-Ogilvy watched men running in all directions to escape; some already burning. ‘Some of our members who I personally assisted were blackened all over,’ Balfour-Ogilvy wrote, ‘clothes were on fire and their clothes had been completely burnt off and when I grabbed them, skin just came off wherever I handled them.’ With such intense heat there was a limit to what could be done and even two American Air Force firefighters ‘wearing asbestos suits and walking into the inferno’ had to retreat. ‘The heat was so intense very little could be done, and to those able to assist, we now saw friends being burnt alive.’ Unable to help the living, Balfour-Ogilvy took on ‘the grim self-appointed task of organising and laying out the bodies and bits and pieces of bodies that the firefighters brought out.’37 A stunned Bill Crooks ‘walked to the control tent to report to the adjutant that D Company was no more’.38 Brigadier Ivan Dougherty arrived and asked Lieutenant Colonel Cotton if the emplaning should proceed after such a tragedy. Cotton asked his three remaining company commanders the same question. Captain Dave MacDougal replied, ‘We go sir, we can’t stop. Morale will drop like a lead balloon, sir.’ The other officers agreed and the remainder of the battalion headed for Durand airfield.39 There was a battle to be won at Lae.

Despite what they had just been through, Bill Crooks and Johnny Beck jumped aboard a C-47 transport for Lae. However, as it roared down the runway, the port engine caught fire and the engineer told everyone to ‘lie down and hold on’ as the pilot tried to stop the plane before takeoff. It finally slewed to a halt against the side of a revetment with a burst tyre, and Crooks and Beck, their nerves shot to pieces, were ordered to hospital and treated for shock.40

The bodies of fifteen Australians and the eleven American airmen were recovered from the crash site. John Balfour-Ogilvy could ‘clearly recall 14 bodies, burnt beyond recognition, heads, legs and arms completely burnt off, leaving bodies only, like charred blocks of wood’.41 It was only the beginning: another 47 would die from their burns and 89 more were injured, many of them horrifically maimed. Of the 62 Australian dead, 60 were from the 2/33rd Battalion and two were drivers from the 158th General Transport Company.42 Dave MacDougal summed it all up: ‘so many mates gone’.43

•

The work of the 871st Airborne Engineers at Nadzab continued full-time under lights, at times in torrential rain and always under threat from Japanese ground and air forces. The first transport aircraft landed on the new gravel strip at 0800 on 10 September, less than 48 hours after work had begun. Three days later a parallel gravel strip was in operation with a taxiway and eighteen hard stands also completed.44

On 8 September the 2/25th Battalion’s pioneer platoon was flown in to help the engineers working on the airfield. Later that afternoon, C Company of the 2/33rd Battalion also arrived and by midday the next day the rest of the weakened battalion had flown across from Tsili Tsili. That night a heavy rain storm flooded Nadzab airstrip and, much to General Vasey’s annoyance, this delayed the arrival of the 2/31st Battalion until 12 September. Over the six days from 6 to 11 September 420 planeloads had landed at Nadzab. Of these, 333 planeloads (79 per cent) flew in from Tsili Tsili and 87 directly from Port Moresby.45 The secret airfield at Tsili Tsili had proved vital to the success of Operation Postern.

Sergeant John Rutherford was one of the men who flew to Nadzab from Port Moresby. ‘We are to be airborne to Nadzab,’ he wrote. ‘We back our truck to the gaping doors, transfer our load into the bowels of the waiting monster, and take our seats.’ For many of the men, powered flight was a new experience. ‘The motors roar furiously, our monster vibrates alarmingly,’ Rutherford wrote, ‘then slowly, ever so slowly, we trundle forward, gradually picking up speed until, soon, we are literally hurtling along as though bent on destruction.’ Crossing the Owen Stanley Range, the men watched ‘Huge jagged peaks, seemingly within reach, thrust their sinister tops menacingly through the clouds.’ Once over the range, Rutherford saw ‘a rough-looking burnt clearing on which descending planes were playing a game of “follow my leader” as, in a whirlwind of black dust, they jolted down the short runway.’ After disembarking, Rutherford observed ‘Nadzab! A centre of confusing noise and bustling activity; of shouted orders and jabbering natives; a hell of dust and heat and roaring planes.’46

•

Major General Ryoichi Shoge, the commander of the 41st Division infantry group, was put in command of the defence of Lae. Lieutenant General Kane Yoshihara later praised Shoge’s attitude of cool courage as the ideal for a commander. Yoshihara considered him the original taciturn samurai, who would go for a day or two without opening his mouth if there was no reason to do so. Yoshihara wrote that ‘silence is superior to eloquence on the battlefield’ and that Shoge ‘was a fighting man who did not display signs of joy or sorrow, pleasure or pain’. Shoge held the ‘enemy back to the east and west, even while they were within such close range, he was a model of coolness … the composure of the commander made the officers and men steady down’. Yoshihara also singled out an operations staff officer, Major Masatake Mukai, for note, writing how Mukai acted as platoon and company commander as he went to the most forward positions to direct the fighting.47

The lack of a mobile Japanese force that could respond to the Nadzab landings was a major flaw in the Japanese defence plan. A section of artillery within range of the airfield, directed from any number of excellent lookout positions in the hills above the airfield, would also have significantly delayed operations at Nadzab. On 5 September General Berryman wrote that ‘enemy is weak and fully occupied at Lae by 9 Div. However if enemy had a strong mobile force our [position] could be serious if he attacked Nadzab in strength.’48

Prior to the Lae operation, Rear Admiral Kunizo Mori had been ordered to replace Rear Admiral Ruitaro Fujita as the commander of the 7th Base Force at Lae. This command covered most of the naval forces present at Lae. On 9 September, at the height of the battle for Lae, Mori arrived at Lae from Rabaul on the submarine I-174, and Fujita returned to Rabaul on the same vessel.49 With most of the naval forces in Lae allocated to support tasks, it would be the Japanese army units from Salamaua that would bear the brunt of the front-line fighting in defence of Lae.

•

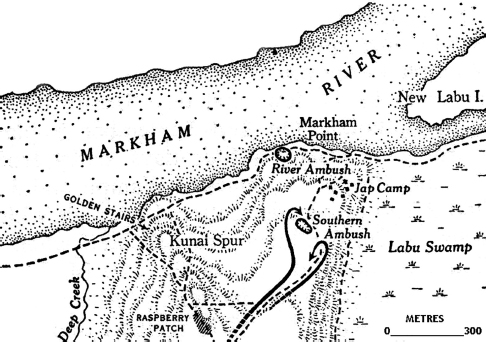

While Vasey’s 7th and Wootten’s 9th Division provided the main clout for Operation Postern, there was a third division involved, that being Major General Edward Milford’s 5th Division, operating south of the Markham River and engaged in the battle at Salamaua. Milford’s role in Postern was twofold. The first role was to maintain the pressure on Salamaua to hold the Japanese troops there and prevent them from moving to Lae. The second role was to directly threaten Lae by pushing along the coast from Salamaua and by driving the Japanese from their major position on the south bank of the Markham River at Markham Point (see Map 12).

Lieutenant Colonel George Smith’s 24th Battalion, which had operated in the vast area between Salamaua and the Markham River for three months, was given the task of attacking Markham Point. On 11 August Smith’s battalion, less one company but with a PIB company attached, was designated Wampit Force and came under the direct command of New Guinea Force. Its initial role had been to prevent any Japanese incursion into the Wau and Bulolo area and to continue building a jeep track through to the Markham River.50

Smith’s battalion was now ordered to make a company-sized attack on Markham Point, the dominating enemy position on the southern bank of the Markham River, which covered the best crossing point of the Markham where it split into two channels either side of Labu Island. The position was garrisoned by just over 100 soldiers from the 2nd Battalion of the 238th Regiment.51 The attack was originally to take place on 5 September, but on 3 September Smith received orders to attack the next day, 4 September, the day of the amphibious landing. The attack would act as a diversion for both the amphibious and airborne phases of Operation Postern. As Captain Clyde Bunbury later wrote, the attack was ‘a diversion from NADZAB … Hence there was NO intention or need to destroy the MARKHAM PT garrison’. However, Smith was hampered by a poor air-supply situation which had left essential supplies that had been dropped on 2 and 3 September scattered, and a chronic shortage of native carriers to bring those supplies forward. Smith had less than 90 carriers available to move some 2200 loads. Captain Ted Kennedy excelled by accompanying the carriers on four return trips from the supply base at Wampit to the front line in the time normally allocated for a single trip.52

Captain Arthur ‘Reg’ Duell, the C Company commander, would have four platoons available for the attack on Markham Point plus two Vickers machine guns and two 3-inch mortars in support, about 120 men in all. However, due to the need for security leading up to Operation Postern he had minimal time to study the Japanese defences and deploy his men. He was also hampered by having to wait for his battalion commander at Deep Creek, well back from the start line. Lieutenant Fred Childs’ 14 Platoon would make the initial attack from the south-west followed by Lieutenant Maurie Young’s 13 Platoon, which would push down off the ridge to the river. The other two platoons would cover the company base area while the mortars would target the Japanese camp on request and the two Vickers guns would fire on Labu Island to hamper any Japanese reinforcement or retreat.53

The Japanese defenders had been dug in behind barbed wire for several months astride a razorback ridge abutting the fast-flowing Markham River to the north. It was a well laid out position with a small village of living quarters and training areas about 400 metres back from the front lines.54 Having only reached the area on the afternoon of 3 September, Fred Childs had little time to plan an attack that would be based on next to no knowledge of the enemy strength and dispositions. Another problem was that Childs had only just taken over command of the platoon so he had not yet built up the rapport with his section commanders that was vital for controlling such an action.55

Childs’ platoon moved up towards the start line late that afternoon accompanied by Young’s platoon and the Vickers gun section. The men struggled with the Vickers guns on the steep slopes and dropped behind, further delaying the deployment. When dark came, the two platoons were unable to find the track which led to the start line so laid up for the night further back.56 The lead elements would rely on surprise so there would be no preliminary mortar bombardment, but, without enough signal wire to connect a line to the forward units, there would be no mortar support on call either. ‘It cannot be wondered that the troops were feeling that they too were expendable,’ one of the mortar men observed.57

Before first light on 4 September Childs’ platoon moved out. The men in the two lead sections formed an extended line below the ridge and advanced up to the enemy position. A one-metre-high barricade made of dead logs extended along the slope below the top of the ridge with five firing lanes cut into the grass facing north towards the river. The men of Corporal Harold Blundell’s and Corporal Henry Gray’s sections moved across the fire lanes and climbed over the chest-high barricade, fortunately into an unoccupied enemy position with empty weapon pits strung out along the ridge. However, the Japanese had laid a number of booby traps and, when one was set off, John Sullivan was killed and four other men wounded. One of the wounded, Private James Walker, pulled a shard of metal from his chest and continued. Blundell moved east down the trench and then along a track that continued up the spur. Here he encountered an unarmed Japanese soldier moving towards him along the track, probably to check what had set off the booby trap. Blundell fired three bursts from his Owen gun at four paces and then went back to find Childs. Blundell then shot another enemy soldier moving down the track before moving off the ridge. He was with three other men when heavier fire came their way, wounding Len Whitby in the leg as he crossed a barricade. Blundell then pulled his men back out of the fighting.58

Fred Childs had led one section past the first line of weapon pits and along the track towards the Japanese camp before heavy machine-gun fire forced the men to ground. Childs was wounded in both legs by a burst of fire and was left behind within 15 metres of the enemy lines. He could hear the Japanese defenders talking and moving about, firing regularly down the cut fire-lanes and throwing grenades. Just after dark, Childs decided to try to crawl out and after about 10 metres he met up with the four men from Gray’s section. Afraid of the noise they would make in the dark, they all waited for the dawn when they were able to move back through a swampy area. However, the Japanese heard them and followed. Childs despatched one with his pistol but the other four men who were further away got involved in a fierce firefight with their pursuers. When Childs got to them only two were still alive: James Walker, who had been shot through the legs and had a broken arm, and Herbert Wilson, who was in a very bad way after enemy fire had broken his back.59

Childs, Walker and Wilson lay there all day and throughout the next night, with Wilson delirious, calling out for water. On the morning of 6 September, with no prospect of help, Childs and Walker began to crawl out, leaving the immobile Wilson, who asked Walker to arrange for his mother to be written to. Coming across an enemy position, Childs and Walker waited until the night to move past. It was now the night of 6–7 September and as the two men crawled through the Japanese camp they were grateful for the rain which provided much-needed water to allay their thirst. Next day they continued on past enemy weapon pits towards the Markham and on the afternoon of 8 September they met up with an Australian patrol along the bank of the Markham River. The rest of Gray’s section never made it back. Henry Gray had been killed and Bill Hellens shot through the ankle. Allan Betson and Russell DeLacy helped carry Hellens out but the three men were never seen again.60

Captain Reg Duell then went forward with Maurie Young to see what was happening. The two officers moved up along the west side of the spur, entered the Japanese position unopposed and found two of Childs’ men there. Leaving Young just outside the position to await his platoon, Duell returned to the start line and sent the rest of Young’s men up; however, when the platoon arrived, Young could not be located. Although Duell said that ‘his body was discovered later’—and despite that claim being repeated in the Australian Official History—Maurie Young’s body was never recovered and remains missing to this day.61

The action had been a costly failure for the Australians, with twelve men killed or missing and another six wounded. Duell’s new orders were just to contain the enemy position.62 George Christensen, who was with the mortar section at Markham Point and later wrote the battalion history, called the operation ‘The Balls Up’.63 The fact that the remains of four Australian soldiers from this action remain missing to this day indicates that ‘The Balls Up’ didn’t end there.64