7

KILLING TOMORROW: NEVER-ENDING WARS, ETHNIC CLEANSING, TERRORISM, SHIFTING BOUNDARIES

Once, I remember, we came upon a man-of-war anchored off the coast. There wasn’t even a shed there, and she was shelling the bush. It appears the French had one of their wars going on thereabouts. Her ensign dropped limp like a rag; the muzzles of the long six-inch guns stuck out all over the low hull; the greasy, slimy swell swung her up lazily and let her down, swaying her thin masts. In the empty immensity of earth, sky, and water, there she was, incomprehensible, firing into a continent. Pop, would go one of the six-inch guns; a small flame would dart and vanish, a little white smoke would disappear, a tiny projectile would give a feeble screech – and nothing happened. Nothing could happen. There was a touch of insanity in the proceeding, a sense of lugubrious drollery in the sight; and it was not dissipated by somebody on board assuring me earnestly there was a camp of natives – he called them enemies! – hidden out of sight somewhere.

This image, from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, is one of the most arresting and surreal accounts of violence for its own sake. Much as the inhabitants of Easter Island, cut off from the world in an eerie silence, gave themselves up to absolute war, so here the gunboat of a French colonial enterprise fires on a whole continent in a purposeless gesture that has taken on a life of its own. Perhaps the crew think they see an enemy to be fought, but no observer can detect why they are shooting or at what. Military violence creates a new situation, a different relationship to the world from the one that existed or was even imaginable before. Conrad’s description was based not on the powers of literary imagination but on his own experience. As an employee of the Société Anonyme pour le Commerce du Haut Congo, Conrad/Korzeniowski had travelled up the River Congo to pick up a team of workers from Stanley Falls – although he never made it to his destination. His African experiences threw him into such despair that he switched his life as a colonial trader for that of a novelist. Heart of Darkness painted a vision of unfettered violence so powerful that, eighty years later, it provided the basis for a film about a much more recent, though no less demoralizing, form of anonymous violence: Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now.

In contrast to other objects of social theory – work, media, demography, art, etc. – violence is only to a very limited degree, if at all, part of the experiential world of the academics who concern themselves with it. As a result, little explicit research has been devoted to this central area of human action, and even that is overloaded with moralism and fantasy. Being seen as something alien, violence is an unclear and threatening theme to tackle. In recent decades it has mainly been historians who have focused on it, dealing with processes that are now over and done with and therefore less dangerous than present-day or likely future events. Besides, the history of human violence, unlike that of other cultural phenomena, is fairly well documented. This speaks for its fundamental importance for social relations.

WARS

We are cultural animals and it is the richness of our culture which allows us to accept our undoubted potentiality for violence but to believe nevertheless that its expression is a cultural aberration. History lessons remind us that the states in which we live, their institutions, even their laws, have come to us through conflict, often of the most bloodthirsty sort. Our daily diet of news brings us reports of the shedding of blood, often in regions quite close to our homelands, in circumstances that deny our conception of cultural normality altogether. We succeed, all the same, in consigning the lessons of history and reportage to a special and separate category of ‘otherness’ which invalidates our expectations of how our own world will be tomorrow and the day after not at all. Our institutions and our laws, we tell ourselves, have set the human potentiality for violence about with such restraints that violence in everyday life will be punished as criminal by our laws, while its use by our institutions of state will take the particular form of ‘civilized warfare’.1

John Keegan is doubtless right when he notes the peculiar refusal to come to grips with today’s war and violence and to accept that it is closely bound up with characteristically modern forms of communication. It may be the fact that 90 per cent of wars since 1945 have been fought outside Europe and North America which has led to the Western notion that they should be viewed as a problem for other societies, especially ones whose forms of statehood have not yet reached the level of OECD countries. Military violence can thus be regarded as an anomaly, although the murderous twentieth century is only just over and war clearly has a great future.

In any event it had a great past after 1945. Since then there have been more than 200 wars in the world,2 with a tendency to become more frequent until the early 1990s and a reverse tendency in the years since then. There have been roughly fifty wars each in Asia, Africa and the Middle East since the end of the Second World War, thirty in South and Central America, and fourteen in Europe. Only North America has remained free of armed conflict through this period. However, the fact that wars in Europe have made up only 7 per cent of the post-1945 total tells us nothing about the frequency with which Western countries have taken part in violent international conflicts; for Britain has been involved in nineteen, the United States in thirteen, and France in twelve. We should remind ourselves that in 1982 Britain waged a classical interstate war against Argentina over the Falkland Islands, which included the most important naval battle since the Second World War and led to the loss of more than 900 lives.

A sharp rise in the number of wars seemed to be looming in the 1990s, but in reality the figure has since declined by roughly 40 per cent.3 This is partly due to the fact that, in the past fifteen years, more UN-mandated or UN-sanctioned interventions have taken place in violent conflicts (as in Kosovo or Congo), although they have not always been successful in the long term.

Table 7.1 Wars and armed conflicts

| Wars | Start date | Situation in 2005 |

| Africa | ||

| Angola (Cabinda) | 2002 | Armed conflict |

| Burundi | 1993 | War |

| Chad | 1996 | Armed conflict |

| Congo-Kinshasa (East Congo) | 2005 | War |

| Ethiopia (Gambela) | 2003 | Armed conflict |

| Ivory Coast | 2002 | War |

| Nigeria (Niger Delta) | 2003 | Armed conflict |

| Nigeria (North and Central) | 2004 | Armed conflict |

| Senegal (Casamance) | 1990 | Armed conflict |

| Somalia | 1988 | War |

| Sudan (Darfur) | 2003 | War |

| Uganda | 1995 | War |

| Asia | ||

| India (Assam) | 1990 | War |

| India (Bodos) | 1997 | War |

| India (Kashmir) | 1990 | War |

| India (Nagas) | 1969 | Armed conflict |

| India (Naxalites) | 1997 | War |

| India (Tripura) | 1999 | War |

| Indonesia (Aceh) | 1999 | War |

| Indonesia (West Papua) | 1963 | Armed conflict |

| Laos | 2003 | War |

| Myanmar | 2003 | War |

| Nepal | 1999 | War |

| Pakistan (religious conflict) | 2001 | Armed conflict |

| Philippines (Mindanao) | 1970 | War |

| Philippines (NPA) | 1970 | War |

| Sri Lanka (Tamils) | 2005 | Armed conflict |

| Thailand (southern Thailand) | 2004 | War |

| Near and Middle East | ||

| Afghanistan (anti-regime war) | 1978 | War |

| Afghanistan (‘war on terror’) | 2001 | War |

| Algeria | 1992 | War |

| Georgia (South Ossetia) | 2004 | Armed conflict |

| Iraq | 1998 | War |

| Israel (Palestine) | 2000 | War |

| Lebanon (southern Lebanon) | 2004 | War |

| Russia (Chechnya) | 1990 | Armed conflict |

| Saudi Arabia | 1999 | War |

| Turkey (Kurdistan) | 2005 | Armed conflict |

| Yemen | 2004 | War |

| Latin America | ||

| Colombia (ELN) | 1964 | War |

| Colombia (FARC) | 1965 | War |

| Haiti | 2004 | Armed conflict |

Source: AKUF, 2007

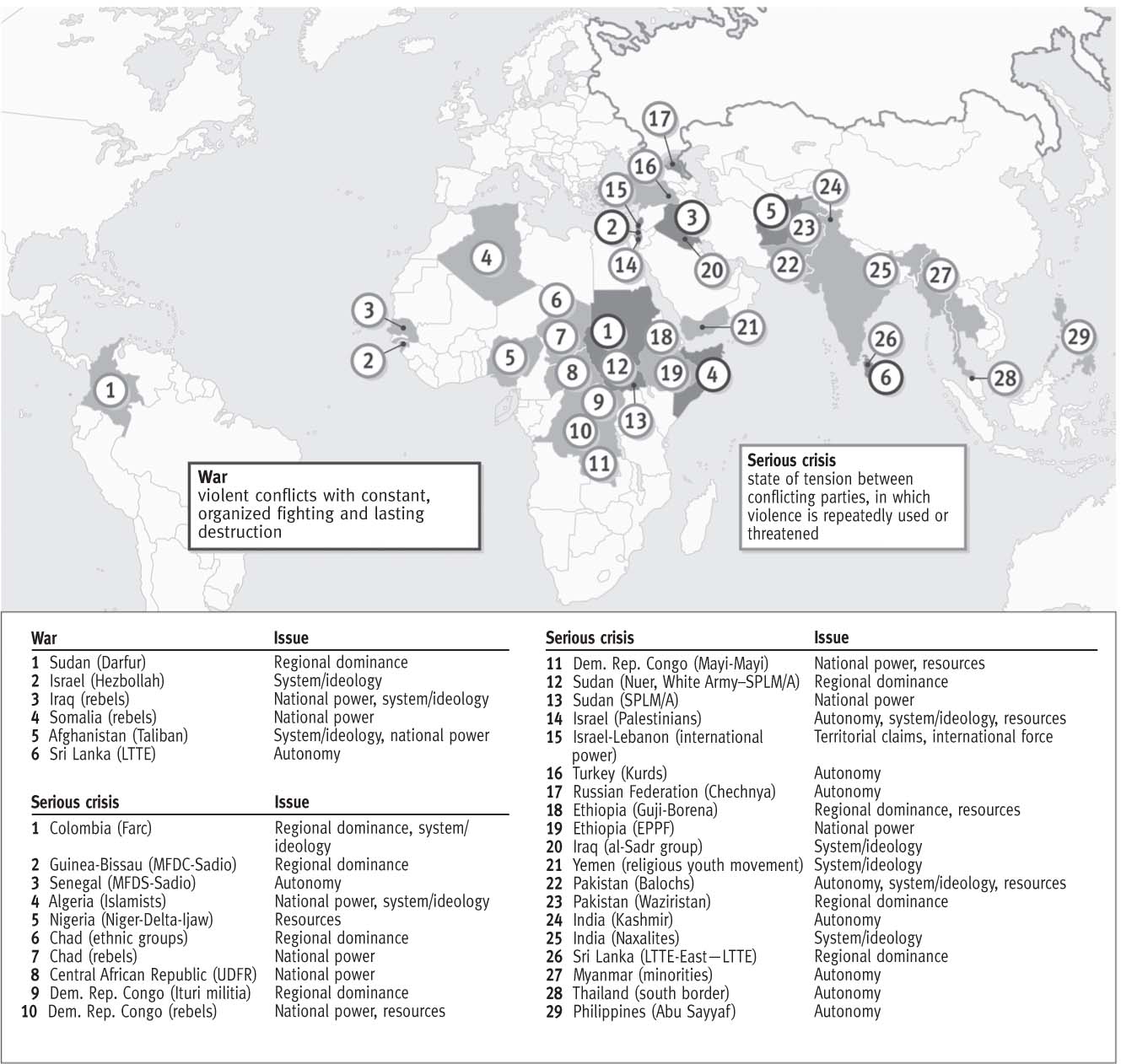

Figure 7.1 Wars and serious crises, 2006

Source: Konfliktbarometer 2006, Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research, December 2006.

Most of the wars since 1945 have been civil wars of a post-colonial or revolutionary nature; only a quarter or so have corresponded to the classical type of an interstate conflict.

In 2006, according to the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research, there were thirty-five major violent conflicts, including six wars (either international or civil, sometimes with more than two sides) (see figure 7.1). However, much depends on def-initions: the Hamburg-based research project Arbeitsgemeinschaft Kriegsursachenforschung (AKUF), for its part, counted seventy-six major violent conflicts in 2006, including civil wars (as in Somalia, Darfur and Sri Lanka) and a smaller number of ‘interstate wars’ (in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Iraq, Kashmir).

Classical interstate wars are not currently being stoked up on a major scale, but three tendencies might change this:

- International commodities markets and supply infrastructure (especially gas pipelines) are a highly sensitive area of ‘global insecurity’.4 Attacks on pipelines, refineries, bridges, and so on, are among the tactics of international terrorism, and local rebel groups (most notably in Nigeria and Iraq) pose a further threat. Similar scenarios are not unlikely to arise in Eastern Europe, where gas pipelines cross a number of countries.

- Conflicts over basic materials such as water will become a major phenomenon in the future: it is estimated that at least 2 billion people will suffer from water shortages by the year 2050, and the gloomiest predictions set the figure as high as 7 billion.5 New conflict scenarios are also appearing in connection with the drying up of lakes that lie across frontiers; in some cases (Lake Chad or the Aral Sea, for example) it suddenly becomes unclear which state or regional authority controls the new territory.6

- Melting of the Arctic and Antarctic ice cover offers further scope for violent conflict. The vast natural resources suspected to lie beneath the ice will soon become accessible, and it has long been disputed who has the right to exploit them. The Russian ‘Akademik Fyodorov’ expedition staked sovereignty claims in summer 2007 by planting a titanium seabed marker to a depth of 4,200 metres; its self-declared mission was to declare the territorial limits of the Russian shelf in the area between the Novosibirsk islands and the North Pole.7 This drew an immediate response from the United States, Canada and Denmark, which all rejected the Russian claims. Britain staked a claim to a million square kilometres of Antarctica, which brought it into conflict with Argentina and Chile.8 The melting of ice also opens us new transport routes and associated economic opportunities, as in the case of the Northwest Passage to Asia, which became navigable for the first time in summer 2007. Both Canada and the United States have established a military presence in the region.

Figure 7.2 Regions affected by water shortage, 1995 and 2025 (predicted)

Source: Philippe Rekacewicz, from UNESCO/GRID.

The potential for conflict within and between states will therefore not diminish in the decades ahead. But, in addition, climate change may lead to new forms of warfare that the classical theories of war did not envisage.

NEVER-ENDING WARS

Extreme violence establishes forms of behaviour and experience for which the largely peaceful Western hemisphere of the post-Second World War period offers no frame of reference. Thus, any analysis should start by recognizing that much about extreme violence is unintelligible from the outside and cannot be explained in conventional theoretical terms. Gérard Prunier, one of the leading authorities on African wars and genocides, stresses at the beginning of his book on Darfur that not all the extreme violence perpetrated there makes sense; retrospective constructions of an inherent necessity are a big mistake that is best avoided.9

One of the hallmarks of a process of extreme violence is that it may generate social conditions and spaces at odds with the need for meaning, or the attribution of meaning, that academic analysts bring to it. Our instruments, methods and theories are calibrated to the assumption that social processes involve causal sequences of action which are capable of explanation. But this may prove mistaken, since – as Joseph Conrad learned from experience – there are social conditions in which meaning as we understand it is completely suspended, but in which social relations persist and people continue to act.

Another important point made by Prunier is that processes of extreme violence are discerned from outside only when they can be associated with a specific interest. The involvement of European politicians in the Yugoslav wars of succession played no small part in the slide into extreme violence, in parts of the country intended to become NATO allies and fellow EU members in the aftermath of the Cold War. The resulting disaster directly affected the interests of Western European states, whose reaction was correspondingly focused. In Africa and other parts of the world such interests may not come into play – for example, when Hutus started massacring Tutsis – and it may take decades for a war to come to the attention of the Western public. Prunier notes tersely: ‘There are no big political, economic or security stakes for the developed world in these conflicts – just the deaths of human beings. The element which could draw wider attention to the problem, the fear of radical Islam, is not even there. Muslims killing Muslims – it is not a subject to arouse passions.’10

This ‘attention economics’11 is a two-way business. While Western societies become involved only if old colonial ties are still a factor or if a vital alliance or source of materials is affected, the local combatants in protracted wars gamble more and more on triggering mass poverty and refugee flows to spur the West into relief initiatives that can be fed back into the economy of violence. This too is a social interaction that finds no place in the theoretical models.

The brief euphoria after the East–West confrontation came to an end in 1989, as well as the related expectation that force would disappear in interstate relations, meant that people tended to overlook the long conflicts that had kept flaring up and dying down in the shadows of the Cold War, sometimes for decades, coming to notice only when they could be interpreted as ‘proxy wars’ between the USA and the Soviet Union. But the examples of never-ending conflict (Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Colombia, Sierra Leone, etc.) suggest that the classical war between states – in which one or both sides declare war and regular armies fight according to the rules of war and international law – may have been given too much prominence in reflections about the presence and importance of war in the contemporary world.

It is highly questionable whether this form of war, the dominant reference in the West, was ever actually the standard model. It may have applied to the First World War, although that has since come to be seen as the primal catastrophe of the twentieth century, whose regular beginning and formal ending conveyed none of the destructive persistence that would repeat itself in even greater horrors two decades later. The Second World War deviated in at least two respects from the classical model: Germany, the chief actor, systematically violated the laws of war to achieve its goals of colonization and annihilation of various human groups; and the concept of ‘total war’ struck at every member of society, erasing the distinction between combatants and civilian population. The violence of this war knew little regulation and few boundaries, and the far-reaching effects, beyond the 50 million killed, lingered on in a trans-generational half-life that reproduced national and international tensions such as those between Germany and Poland or Estonia and Russia.

Neither the so-called liberation wars of Mao Zedong or Pol Pot nor those which the communist regimes then waged against their own peoples can be described in the categories of classical warfare. Nor does the annihilation of whole cities, culminating in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, fit that model. The distinction between ‘old’ and ‘new’ wars, which has been in vogue in recent years,12 therefore appears somewhat questionable. If the references are the Geneva Convention, the Hague Convention and Clausewitz’s theory of war, then earlier regulated conflicts should be seen as an exception associated with particular processes of European state-building, rather than a rule that would make it appropriate to describe them today as ‘old’.

And what of all the violent conflicts that have been, or still are, fought over many decades between Irish Protestants and Catholics, Chinese and Nepalese, Turks and Kurds, Israelis and Palestinians? ‘Low intensity wars’ by no means represent a new dimension of warfare. Rather, everything suggests that heterogeneous forms of violence have existed alongside one another. And if this testifies to anything, it is that violence is always available as an option for social behaviour, a latent or manifest core element of social relations. Members of societies with a stable monopoly of violence usually like to overlook this, but there the violence is simply embedded in a different social relationship; it has become indirect, and is employed only in special punishable cases, but that does not mean it has disappeared. Moreover, when a regulated form of warfare has lasted for a long historical period, it has been, as Keegan points out, the warfare of a ‘primitive’ people, whose violent disputes were contained within highly ritualized practices.13 This all shows that we tend to consider a violent confrontation as war if that corresponds to our historical experience, overlooking the fact that elsewhere violent relations of a different intensity and duration determine the social reality.

But, regardless of whether the new/old distinction holds water or not, one cannot but agree with Mary Kaldor that in the last thirty years, especially in Africa, a type of organized violence has taken shape in which no sharp boundary can be drawn between war and peace,14 still less between legitimate and criminal violence. Similarly, the line of divide between regular and irregular soldiers has gone by the board, and fighting has, as Münkler says, become ‘asymmetrical’: that is, it takes place not between opponents of equal status but between semi-state or private entrepreneurs and populations. Private warlords, close to the government or the opposition, organize violence that helps groups with financial muscle to maintain power and furthers the criminal exploitation of raw materials such as diamonds, precious woods and oil or the production and export of drugs. As a result, the warlords actually have an interest in the continuation of war rather than its conclusion.15

Here the ‘monopolists of war’ are not states and trained experts but semi-state or non-state players who, in pursuing their particular interests, kill part of the population in order to sow fear and terror among the rest. Münkler argues that such asymmetrical wars will shape the twenty-first century. There is much to be said for this, since fragile or failed states are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, and the erosion of state power and the privatization of violence will become more frequent and affect more countries. Climate wars such as the Darfur conflict are thus harbingers of the future, but this does not at all mean that similar processes will engulf the OECD countries, for example. On the contrary, the power, welfare and security gap between first world countries and fast-developers, on the one hand, and the countries of the third world, on the other, will widen still further, resulting in the entrenchment of global inequality and discord.

According to Mary Kaldor, five groups of armed players appear in these protracted wars. First of all are regular armies, whose weakness may mean that their role is highly problematic in the context of fragile or failing states. Poorly trained and equipped, often receiving little or no pay, such soldiers are more likely to be recruited by private entrepreneurs than to serve as loyal representatives of the public weal; national armies then turn into an undisciplined force displaying symptoms of breakdown. At the same time, they overburden the state budget with weapons purchases, produce sizeable military elites and lower the threshold of violence in society. As Keegan writes, ‘Western “technology transfers”, a euphemism for selfish arms sales by rich Western nations to poor ones that could rarely afford the outlay, did not entail the transfusion of culture which made advanced weapons so deadly in the hands of the West.’16 Not infrequently, parts of the regular army put themselves up for sale, or split off under the command of an officer who has decided to set up in business on his own account. Such developments were seen in Yugoslavia, as in Tajikistan and Zaire.

These split-offs then become indistinguishable from para-military groups, which, like the Janjaweed in Darfur, consist of discharged or turncoat soldiers, youth gangs, criminals and assorted adventurers, often too of children and teenagers. Such paramilitaries may be close to either the government or the opposition. In the first case, they undertake actions that serve the purposes of the government but for which it cannot accept responsibility; in the second case, their task is to fight against the existing government. These roles may be reversed, of course, if circumstances change.

Self-defence units are the third group of armed players. Formed in response to attacks by regular troops or paramilitaries, they do not have an effective military potential and do not usually remain in existence for long.17

Of greater significance are the private military companies (PMCs) and foreign mercenaries, usually veterans from West and East European armies or mujahideen from Afghanistan, or ‘often recruited from retired soldiers from Britain or the United States, who are hired both by governments and by multinational companies and are often interconnected.’18 Such professionals of violence, rooted in the private sector of the economy, play an especially important role in tasks such as torture and blackmail, which governments are reluctant to take on directly because of the potential for scandal. PMC personnel have also operated in the latest wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, performing guard duties, pursuing terrorists, training local police and militias, and so on. In 2003 alone the US government signed 3,512 contracts with companies for security functions.19 In Kenya there are some 40,000 policemen in comparison with 300,000 employees of private security firms.20 The number of non-state armed players on the American side in the Iraq War stood at roughly 50,000. ‘Most private contractors do support jobs such as logistics, training, communications and intelligence, catering and laundry; … when the scandals about torture in the Abu Ghraib prison became public, it was evident that private contractors had carried out some of the most dubious practices.’21 The killing of civilians is also often attributed to them.22

A fifth group of players is regular foreign armies, acting under the umbrella of the UN, the African Union or NATO, which are supposed to prevent genocide or ethnic cleansing, provide security at elections or monitor ceasefire agreements. Often numerically weak, they are also in the precarious situation of not being accepted by the local population and having a limited mandate to use force. Other players may deliberately target them to provoke an overreaction or attacks on civilians, which can then be used as a weapon against the intervention force in the global media. An extreme case of failure on the part of an intervention force was the withdrawal of Dutch UN troops from Srebrenica in 1995, which opened the way for a massacre of approximately 8,000 adult men and youths.

VIOLENCE MARKETS

Never-ending wars generally involve heterogeneous, fragmented groups of players which, with the exception of intervention forces, use less violence against other such groups than against the civilian population. The late social anthropologist Georg Elwert described the social spaces in which they do this as ‘violence markets’ – a term which emphasizes that privatization and economic factors of violence are a central element of never-ending wars, and that the economic strategies in question ‘appear thoroughly profitable to the entrepreneurs of violence that pursue them’. The ‘appeal to culture, ethnic traditions and religion is here one resource among others’ for stirring up and maintaining the armed conflict, as are emotions such as hate or fear, which were not a structural element in the origination of the conflict.23 Indeed, such emotions often appear first with the outbreak of violence, but then have a tendency to become self-perpetuating and to fuel new sources of violence.

As we have seen, the lack of a stable monopoly of violence offers niches and opportunity structures for the private deployment of violence. Such spaces are ‘open to violence’, and it is the coupling of these with market interests that establishes the violence market. In Elwert’s analysis, this is a field of action defined by acquisitive goals, involving the exchange of goods (weapons, drugs, food, local raw materials, hostages), theft and various combinations of the two, such as road tolls, protection money and kidnapping for ransom money. ‘Protection money (also called tolls) and hostage-taking develop as intermediate forms between trade and robbery…. Diamond smugglers in present-day Zaire, khat dealers in Somalia, emerald smugglers in Colombia, and not least the convoys carrying food relief in Somalia and Bosnia make this the main economic sector by income in certain periods.’ Here too it is clear that kidnappings, as in Iraq or Afghanistan, are very rarely attributable to the political calculations that serve to camouflage them, but are part of an economy of violence in which politics, faith and ideology are tools rather than ends in themselves.

The production of violence itself takes place within an economic perspective. If the fighters supply themselves, by robbing and pillaging, this reduces costs for the warlords and assists their strategy of implanting violence in the region: the aim is to sow fear, to trigger refugee flows and to facilitate the recruitment of fighters or forced labour. The instruments of violence are not expensive: handguns, Kalashnikovs, simple rocket launchers and light trucks do the brunt of the work; Darfur showed how easily ordinary petrol cans may be turned into fire-bombs. So, one is speaking of low-tech means, which have the advantage of costing little and requiring no special operational skills. Murder or intimidation can be practised cheaply and efficiently.

The fact that violence is directed less against another armed party than against civilians is one of the key features of never-ending wars. The unleashing of refugee flows, the speedily erected camps and the ensuing relief operations by the international community are important resources for the economy of violence. Relief convoys can be used to supply one’s troops with weapons and food, and it is even possible, as it were, to order the delivery of provisions from abroad by means of targeted actions against the civilian population. Considerable sums can also be raised in tolls and protection money for allowing aid convoys to pass unhindered, and almost intact, along the road to a refugee camp. The camps themselves become arenas for political or religious agitation, and not least for the recruitment of new fighters and all kinds of labour. There are subtle and not so subtle ways of exploiting international aid in crisis situations.

Wars in certain regions of the third world have something disturbingly opaque about them, and even the war in Yugoslavia, so close to the West geographically, had an uncanny exoticism not unlike that of Rwanda or Darfur. In Africa it could be put down to a ‘tribal conflict’, while here the special culture of the Balkans was supposed to account for the astonishing escalation of violence.24 Such explanations serve to reduce the dissonance that open violence, injustice and human rights violations produce in those who live in better worlds and have made it their political and cultural task to enforce human rights globally or, in the event of breakdown, to provide material assistance.

So, in order to reduce the moral dissonance that Rwandan genocide produces in Germany, every effort is made to help the victims – or anyway those who have escaped with their lives. Mobile hospitals, doctors and nurses, medicine, blankets, tents and food: all these have to be transported, often with considerable difficulty, to the affected region, and that costs a lot of money and involves a lot of ‘wastage’ along the way. The armed combatants exploit this Western mode of dissonance reduction, to such an extent that they deliberately add to the West’s moral dissonance; they sow violence and reap the harvest.

In a different context, Erving Goffman called this exploitation of institutional structures ‘secondary adaptation’25 – and this is precisely the parasitic manner in which violence markets relate to other economies. But by now the system of secondary adaptation has become so routinized that protection money and wastage quotas are built into the calculations of aid agencies and the strategies of the entrepreneurs of violence. This two-way link between aid and violence is an interesting example of how the conditions and consequences of action can be interconnected in ways that are unexpectedly straightforward.

To be sure, this is not the only resource that the entrepreneurs of violence utilize. Along with robbery of civilians, exploitation of raw materials, organized smuggling and dealing in drugs and weapons, hostage-taking and subcontracted violence, the respective diasporas pump in money from outside to support their ‘we group’ in the escalating conflict. This was particularly striking in the wars in the former Yugoslavia.26

Violence markets are a radical form of free market economy, in which goods are purchased, used and passed on where the potential for violence is greatest. Its spread usually weakens traditional sectors in the region: trade, industry and agriculture fall into crisis, as they are unable to obtain supplies from outside or to reach sales outlets. It is therefore not surprising that the entrepreneurs of violence have sometimes engaged in other economic activities, before branching out in accordance with the new structure of the market. The same is true of the practitioners of violence, who may have previously been employed in small-scale industry.

Such forms of organization have consequences for the processes and dynamics of development. First, it may be completely unclear who took a particular decision or initiated a particular situation, and when and under what circumstances this happened. Second, in the development of violence, conditions come about that did not exist previously, and which perhaps no one had foreseen or intended; interviews with killers caught up in a mass escalation of violence repeatedly display confusion about how they actually came to kill, rape and plunder.27

According to Georg Elwert, violence markets have a strong tendency to stabilize, since persistent violence and threats of violence have removed other possibilities of reproduction. ‘Violence markets do not arise or exist in a vacuum. They grow out of self-organizing social systems, which as such are geared to exchange with their environment, and they partly continue this exchange in altered forms.’ Violence markets emerge when the state monopoly of violence breaks down, with the result that any conflicts that arise over resources in short supply (land or water, for example) are settled not by the state (the law courts) but by the use of force.

Elwert illustrates the catalytic effect with reference to an older study of events in Somalia by the anthropologist Marcel Djama.

The beginning seemed banal: pastoral communities in the research region had for some time been arming themselves with firearms, so that they could clarify access rights to watering places without having recourse to clan courts, state courts or notaries. This was a cheaper alternative, both for the state and for those directly involved. The state tolerated this development because it relieved it of a burdensome task. Clan systems, which so often feature in journalistic analyses of the Somalia conflict, had little to do with this development. For the accumulation of weapons signalled the breakdown of the clan system and its form of judicial process. At first the state tolerated only low-grade use of arms. But when the state failed to defend pastoral interests after the closure of borders with neighbouring states, access to wells and food aid from Ethiopia became the problem. (Until then, food diverted from international aid to Ethiopia had been marketed cheaply in Somalia.) Those who suffered as a result were not only the nomadic herdsmen but also traders who had made a handsome profit by exporting the livestock in large quantities to Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Yemen in particular was almost completely dependent on these meat imports. As the traders’ business collapsed, they supplied the nomads with large quantities of weapons, so that they could use force to ensure the reproduction of their herds. This is how the so-called Gadabursi militia arose. It soon discovered that it could obtain food almost cost-free at the point of a gun, and that hostage-taking, food convoy ‘taxation’ and protection for drug dealers were lucrative activities.

Here, as under a magnifying glass, we can see how the dynamic of violence first sprang up and meandered its way through the country. It is this progression of violence in societies with a weak or virtually non-existent state which is so difficult to perceive from outside.28 It combines particular interest with collective irrationality. The result is never-ending war.

An Oxfam International study showed that, between 1990 and 2005, wars in Africa cost a total of €211 billion – which corresponds quite closely to the amount of development aid that flowed into the continent during the same period.29

Never-ending wars are a form of violence with a future. We have not yet built the exacerbating consequences of climate change into the picture. But, from the case of Darfur, it is evident that phenomena such as rapid desertification may become new sources of violent conflict, to be channelled and exploited in many ways by groups with an interest. This may be termed the self-catalysing dynamic of the formation and occupation of spaces open to violence. De-statification and the growing fragility of existing states intensify this dynamic, so that the opening of further spaces for violence brings international players onto the scene, increases the resources available for violence, and so forth. The war in Iraq provides the clearest contemporary example of this process.

ADAPTATION

These are all attempts to adapt to changing environmental situations, and the adaptation is expressed in the shape of violence markets and experts, refugees, camps and dead people. Anyone who thinks this formulation too dry should bear in mind that the West’s adaptation strategy for the predicted climate change consists of evoking and forcing a third industrial revolution – a strategy which, as Nicholas Stern has impressively calculated, would be considerably cheaper in the long run than failure to adapt proactively. In fact, adaptation will probably turn out to be profitable for the national economies of the West: a problem will be converted into a locational advantage, because education, technology and funding are available for the transformation. The choice of means and the legitimacy of the strategy are rather different from when a Somali warlord uses his muscle to snatch at the economic opportunities presented by a resource conflict; the latter is, of course, also regarded as morally more questionable than the West’s response to climate change. But what the two strategies have in common is an attempt to convert a problematic situation into a particular advantage. Each can also be given a high-sounding name: the former described as ‘reduction or avoidance of CO2 emissions’, the latter as ‘support for freedom fighters’.

The points made here about never-ending wars only relate to the visible, though also obscure, part of the total configuration of violence. But the role of international aid agencies and intervention forces has made it clear that external players are also part of the configuration. Moreover, aid agencies and UN soldiers are themselves only the visible part of a system of external players that mostly remains unnoticed. We are these invisible players.

To sum up, we may say that the phenomenon of never-ending wars and violence markets will become more widespread and dramatic as the consequences of climate change (desertification, salinization, shrinking water supplies, etc.) make themselves felt. The question then, in a context where violence markets are expanding all the time, will be what scope international agencies have to intervene against genocidal violence, ethnic cleansing, and so on. It is already likely that international troops and special forces will be unavailable on a sufficient scale. For intervention itself is a scarce resource, which, reason tells us, can be distributed only in the interests of those who intervene. Or, to put it more simply, if such interests are not affected – if people fight among themselves and power politics, strategy or resources are not the issue – then the countries in the grip of violence will be left to get on with it.

Any moral dissonance related to this can be reduced in many different ways. It can be argued that it is wrong to meddle in the internal affairs of another country, that it is more important to play an active role in other crisis regions, that the risks for one’s own troops are too high, that intervention might lead to ‘mission creep’, that local forces on the ground are better able to handle conflicts, that mistakes can be made, as in the past, and the wrong groups supported, and so on. Of course, it might then be further argued that the entrepreneurs of violence should no longer be given the opportunity to exploit humanitarian relief operations, and that a halt should be called to investment in the violence market economies. That would be another stage in the adaptation to climate change.

ETHNIC CLEANSING

For expulsion is the method which, so far as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble as in Alsace-Lorraine. A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed at the prospect of the disentanglement of population, nor am I alarmed by these large transferences, which are more possible than they were before through modern conditions.30

These matter-of-fact words of Winston Churchill referred to the postwar situation of the so-called ethnic Germans in Poland and Czechoslovakia. When, as prime minister, he spoke of expulsions to the House of Commons on 15 December 1944, it was already taken for granted that there would be no mixed populations in the territories formerly occupied by Germany. Once the war was over, this idea of ethnically homogeneous states turned as many as 14 million ethnic Germans into refugees and expellees; roughly 2 million lost their lives in the process, and several hundreds of thousands were deported and made to engage in forced labour.31

That was probably the largest population movement of the twentieth century, but it was not the only one. All the transfers, whether in the form of expulsions, ethnic cleansing, deportation or official population exchanges, were the result of a path to modernity that ran through the creation of ethnically homogeneous states; they were one aspect of modern nation-building. Heterogeneous populations, causing ‘endless trouble’, were always regarded as a potential or actual obstacle to national development, and Churchill’s view that even extensive resettlement would pose no special problems harked back to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which provided for large-scale population transfers of Greeks from Anatolia and Turks from Greece following the end of the Greco-Turkish War. This exchange of approximately 1.5 million Greeks and 350,000 Turks, which took place under the auspices of an international commission, did not count as inhumane but was seen as a rational strategy for the homogenization of nation-states that would reduce the risks of future conflict.

The modern age has witnessed a whole series of ethnic cleansings, some of which (as in Armenia or in Stalinist strategies for the building of a new order) turned into genocide. These cases of mass killing did not always involve an escalation of violence; they could also be due to indifference or a lack of planning, as when tens of thousands of Chechens and Ingush died in Soviet deportation wagons or 100,000 more perished in the first three months after deportation, abandoned without food or accommodation because no one had thought it necessary to provide such things.32

The outcome of Yugoslavia’s break-up wars was the transformation of constituent republics of a federal state into ethnically homogeneous nation-states. Here too the means to the end was ethnic cleansing, and in Kosovo or Bosnia conflicts smouldered on until internationally monitored ceasefires finally took effect. Michael Mann, in his extensive history of ethnic cleansing in the twentieth century, came to the sobering conclusion that it was not the result of failed modernization processes but a sign that modernization had been successful. All Western societies, with the exception of Switzerland, Belgium, Britain and Spain, owe their present nation-state form to a policy of ethnic homogenization, of which ethnic cleansing is the other side of the coin. This is the dark side of the development of democracy, and people simply forget it when they look with horror at the violence in Bosnia.

Against this background, the globalization process has evidently added more than a little to the violence. The more that post-colonial, post-socialist or post-autocratic societies were drawn into the OECD model of nation-state building, the more the potential for violence grew within them, and the more tendencies developed to direct the violence outwards. Radical Islamism, with its violent refusal to join the global process, is only one expression of how this modernization pressure has been experienced.33 The point here is that never-ending wars, refugee flows, ethnic cleansing, and so on, are not the antithesis of modernization but simply part of its costs.

If, Mary Kaldor writes, globalization denotes ‘the intensification of global interconnectedness – political, economic, military and cultural’, then forms of violence such as never-ending wars and ethnic cleansing must be seen in this light.34 The potential for violence arises through changes within the existing structures, not through the clash of intrinsically antagonistic forces such as the current counterposition of radical fundamentalism and Western liberalism suggests. Samuel Huntington’s ‘clash of civilizations’ argument is not fundamentally wrong, because violent conflicts between cultures do exist, but it points only to what others do and fails to see the role of one’s own culture in the action context that the different cultures jointly constitute, and whose conflicts they jointly wage. What is involved is an interaction, partly violent but certainly not as metaphysical and subjectless as a ‘clash of civilizations’; that kind of thing does not exist in the world of the social. Conflicts are interactions, and they connect up the perceptions, interpretations and actions of the various parties.

The greater interconnectedness of cultures changes living conditions for very different human groups. A decisive role is played in this by the rapidly changing information landscape; communication across all cultural differences and geographical distances links together the most diverse cultures and regions of the world, while leaving their life chances and conditions as far apart as ever. Globalization therefore leads to ‘both integration and fragmentation, homogenization and diversification’,35 universalism and nationalism. These consequences are evident in the phenomenon of never-ending war: information about any local skirmish can potentially be communicated and instrumentalized with the greatest dispatch, allowing any number of state, non-state and trans-state players to find pretexts for intervention or business alongside the local antagonists. This is what lies hidden behind concepts such as ‘global interconnectedness, political, economic, military and cultural’, and at the end of these links are human beings in flight, or being killed or rescued, and international criminal courts whose unenviable task it is to unravel the causes of murder and genocide and to judge those responsible for them.

Here a deadly modernization gap opens up. On one side are ‘members of a global class who can speak English, have access to faxes, the Internet and satellite television, who use dollars or euros or credit cards, and who can travel freely’; on the other side are ‘those who are excluded from global processes, who live off what they can sell or barter or what they receive in humanitarian aid, whose movement is restricted by roadblocks, visas and the cost of travel, and who are prey to sieges, forced famines, landmines, etc.’36

At the upper end of the scale, wars and persistent expulsions may generate moral dissonance, but at the lower end ‘stuff like that happens’, and it would be wrong to understand it as ‘tribal’ or ‘primitive’. That may be how it seems, but the causes do not lie there. As the twentieth century showed, there is a close link between modernization and mass violence, and, as Michael Mann put it, ethnic cleansing spreads together with democratization, not against it.

Ethnic rebellions have risen in the South of the world ever since the 1960s and 1970s, the period of its ostensible democratization. They remain low in the North, dominated by institutionalized democracies and the politics of class. During the 1950s they declined greatly in the Communist states, authoritarian and dominated by the politics of class. They fluctuated in the Middle East and North Africa, increased steeply in sub-Saharan Africa after 1960 amid democratizing states, rose after 1965 in Asia, and rose after 1975 in South and Central America. After 1975 all the southern regional trends rose until about 1995. The curve rose as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. After 1995 the trend may have declined a little, except in sub-Saharan Africa, though the overall trend is not yet back to pre-1991 levels.37

In a context of changing spheres of political influence, system breakdowns or implosions of authoritarian rule, the most diverse factors may be interpreted in ethnic categories, especially if they are obscure or downright incomprehensible. Shifting political interests linked to geography, power and resources define an extensive, increasingly global force field, in which environmental factors have until recently scarcely been taken into consideration. However, it is not uncommon for an earthquake, floods or wildfires to lead to looting, demonstrations, revolts or even uprisings; recent examples include the forest fires in Greece38 and the earthquakes in Peru39 and Pakistan.40 In each of these cases, the failure of state-led disaster relief led to unrest, and Greece and New Orleans showed that law and order can quickly break down even in societies with an intact state structure.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICTS

But if climate change affects population distribution and redraws the boundaries of agrarian and waste land, variously producing water shortages and flooding, then this upsets the geopolitical balance and fuels international tensions at the level of power and resource politics. Thus, there is every sign that the twenty-first century will see an increased potential for tensions and a major danger of violent solutions. Michael Mann lines up a number of likely candidates for the next conflicts:

Indonesia will be unable to assimilate or repress Aceh or West Papuan autonomy movements; India will be unable to assimilate or repress Muslim Kashmiris or several of its small border peoples; Sri Lanka will be unable to assimilate or repress Tamils; Macedonia will be unable to assimilate or repress Albanians; Turkey, Iran and Iraq will be unable to assimilate or repress Kurdish movements; China will be unable to assimilate or repress Tibetans or Central Asian Muslims; Russia will be unable to repress Chechens; the Khartoum regime will be unable to contain South Sudanese movements. Israel will be unable to repress Palestinians.41

Conflicts are to be expected in the Baltic too, since ethnic Russians are in a majority in many industrial regions that have suffered extreme environmental damage.42

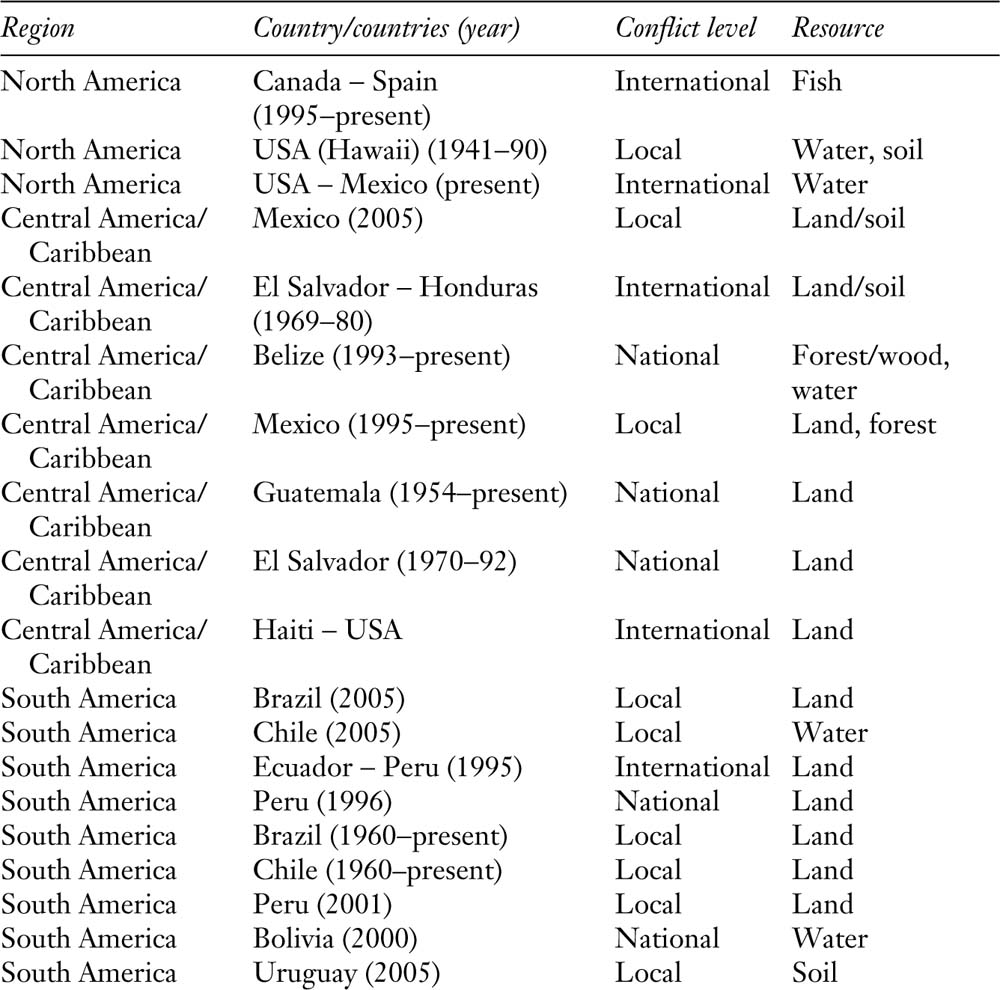

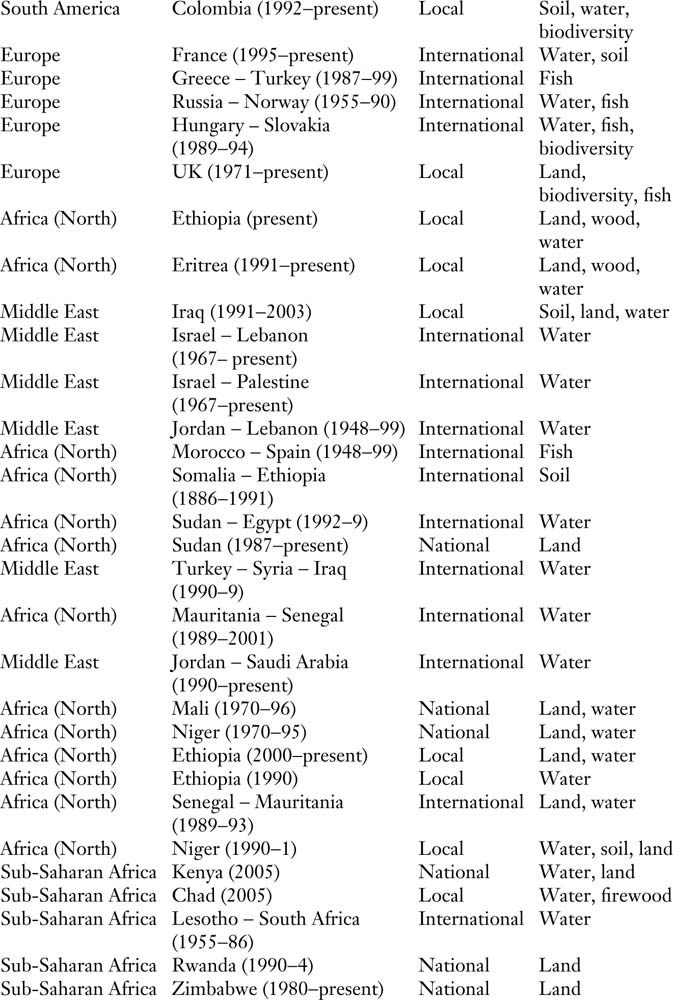

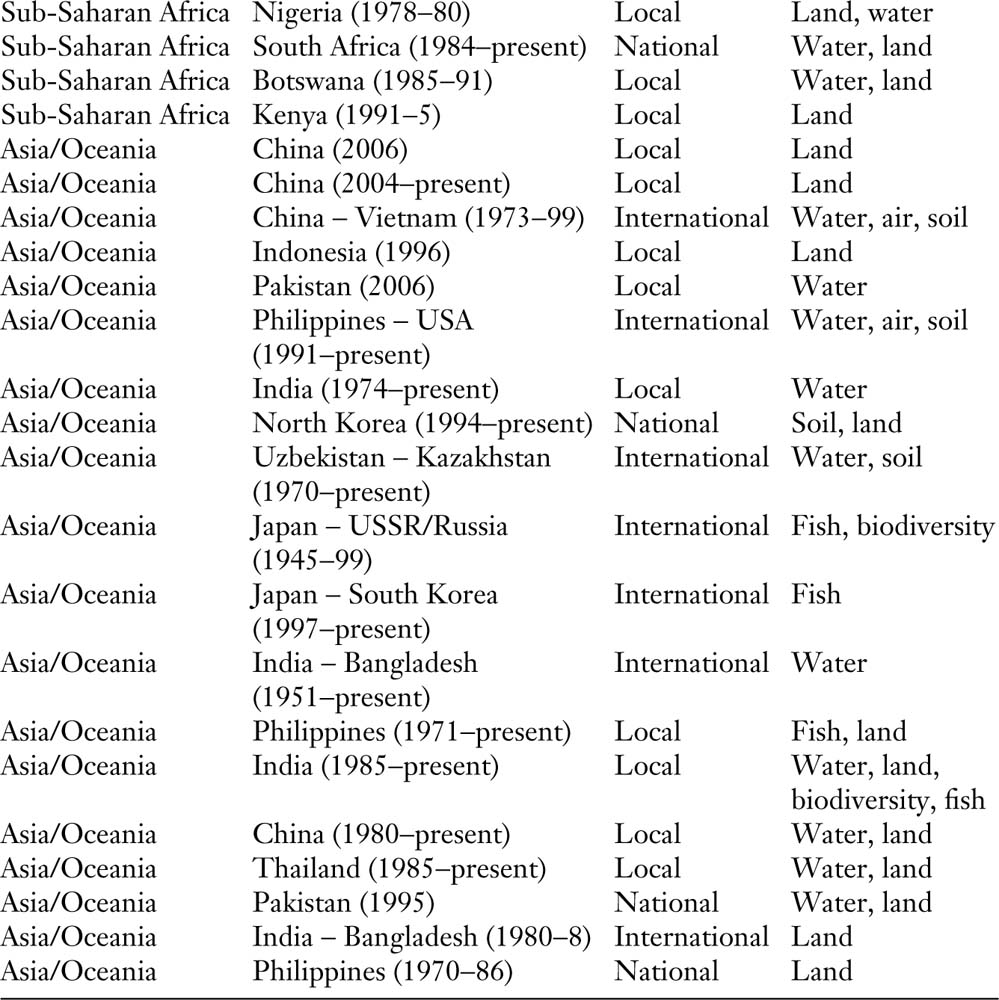

Existential problems linked to climate change will sometimes feed the dynamic for violence, sometimes play no role at all, and perhaps sometimes even calm tensions. But, in each case, the twentieth-century practices that involved the formation of ethnically homogeneous states and the use of ethnically targeted violence will continue to function, possibly on a greater scale than before. Global warming accelerates changes in the configuration of states, raises tensions and creates pressure to find quick solutions. Table 7.2 shows that this is not a gloomy prediction but a part of present reality.

Table 7.2 Violent environmental conflicts

Of course there are no ‘pure’ environmental conflicts, only ones in which several different factors are present. But the WGBU-commissioned research team that prepared this overview, using a definition of environmental conflicts as ‘conflicts that are sharpened or accelerated by the destruction of renewable resources’,43 suggested a fourfold regional typology. The main role in conflicts is played by land use and soil degradation in Central America, soil degradation in South America, water supplies in the Middle East, and both water and soil degradation in sub-Saharan Africa.44 In the first two of these regions, government incapacity and migration are not exacerbating factors; conflicts are driven by poverty, population pressure and the unequal distribution of power. In the Middle East, population pressure, migration, poverty and ethnic tensions dictate the shape of water conflicts, while in sub-Saharan Africa, as we have already seen in some detail, failing states, population pressure, poverty, migration and ethnic tensions are the principal factors. Land use conflicts in Central and South America are far from innocuous. Apart from the effects of deforestation, expulsion takes place on a large scale: 70,000 people in El Salvador, and 200,000 in Guatemala, have lost their lives in the wake of such conflicts.45 Moreover, extreme weather events add to the conflict potential: ‘floods and droughts, in which other existing forms of environmental conflict come into the open, have been on the rise in these regions, with more than 500 victims.’46

A different way of looking at past, present and future conflicts clearly reveals the importance of environmental changes for the development of violence. Previous research has concentrated mainly on economic, ideological and ethnic factors, but a change of focus brings home the role of basic resources such as water, soil and air.

To repeat: violence is never the result of one factor alone. The very phenomenon of modernization pressure, which globalization produces throughout the world, explains the close, though not deterministic, connection between violence (internal or international) and disparities in life or development chances. Every country drawn into the globalization process forms an area of tensions, which are not confined to the level of the state but are also experienced by individuals or groups that economic development puts at an advantage or disadvantage. Direct changes in people’s circumstances are not necessarily the trigger; other factors may have the same effect. The lasting character of modern terrorism, for instance, is due to the fact that it is a child of modernization processes. Flourishing in the global age, it expands both quantitatively and qualitatively into military-style operations, which, like all modern trans-individual forms of violence, are directed mainly at civilian targets; and its protagonists, when they do not come from central locations in the society they attack, are mostly second-generation immigrants or people who have studied or worked in the West. Of course, climate change is only directly linked to anti-Western terrorism and will depend in future on real and perceived asymmetries in the world that global warming induces. As a self-empowering form of substitute warfare, terrorism is therefore likely to grow and has a place in any discussion of killing tomorrow.

Terror spreads with the growth of worldwide migration. The modernization of further societies confronts more and more people with the exigencies of freedom and problems of meaning, especially if it creates a sense that the world is divided into winners and losers. For this reason societies like China or India, in the throes of radical modernization, are already preparing for the time not many years ahead when they too will have a major terrorist problem. Islamist terrorism will have fewer recruitment problems as global communications shrink space, and as the gap in standards of living widens. Climate change may not be a cause of violence, but its unequal consequences are certainly a spur for it – hence questions of justice will become increasingly important in relations both between countries and between generations.

ENERGY CONFLICTS

The role of energy in future scenarios of violence is the reverse side of the carbon emissions problem. In a bizarre equation, the limitless energy hunger of the industrial countries, both old and new, sharpens the struggle for the resources whose depletion endangers the survival of humanity. But the deadliness of this equation is not much talked about. Michael Brzoska points out that, whereas territory used to be the main resource over which states waged war, ‘industrialization meant that raw materials such as coal and oil became casus belli’.47

All debates about the future of fossil fuels revolve around the magical ‘peak oil’ formula, the point in time after which supplies can only diminish. It may seem surprising that we still do not know how much oil remains beneath the earth’s surface, but it is safe to assume that the quantity is finite and that, squeezed between rising demand and growing difficulty of access, the central resource of industrial societies will become more expensive and subject to more intense competition.

The Energy Watch Group calculates that the maximum output of 81,000 barrels of oil a day was reached in 2006, so that we are already past the peak, while the International Energy Agency (IEA) assumes that further increases will be possible in the future as soaring oil prices fill the corporate coffers and encourage new investment in exploration. Whatever the reliability of these predictions, one cannot fail to be disturbed by the general lack of clarity about existing reserves and the scope for future use. After all, 80 per cent of global primal energy use comes from coal, oil and gas, and the figure is rising by a yearly average of 1.6 per cent. Oil consumption alone, which accounts for a third of the total, will rise from 84 million barrels a day in 2005 to 116 million barrels in 203048 – in conditions where, as we said, access will become increasingly difficult. Oil, according to Wolfgang Sachs,

is more important than gold ever was. The industrial system would break down without it: industry and jobs rely extensively on the use and processing of crude oil; transport and mobility, by land, air and water, are essentially dependent on refined oil products; and so too are plastics, medicines, fertilizers, construction materials, dyes, textiles and much more else besides. The dependence on oil has been continually increasing since the middle of the last century; it has become a politically, economically and even culturally irreplaceable resource. Oil, more than any other material, has put its stamp on lifestyles all over the world.49

Not only does this generate emissions on a horrific scale; it also increases political dependence on the producer countries (Iran and Russia together dispose of half the world’s natural gas reserves). Of the twenty-three countries ‘that derive a clear majority of their export income from oil and gas, not a single one is a democracy.’50 Wolfgang Sachs is right when he says that ‘conventional economic development based on fossil fuels has become a great risk for security in the world’.51 Here too the changed power configuration of world society plays an important role; China’s trade with Africa will be worth $100 billion by 2010, and thirteen out of fifteen oil companies active in Sudan are Chinese.52 The economist Dambisa Moyo contrasts China’s strategy with Western development aid: ‘In five to ten years the Chinese model has created more jobs and infrastructure in Africa than the West did in sixty years.’53

Lastly, international commodities markets and supply infrastructure (above all, gas pipelines) are a highly sensitive field of ‘global insecurity’.54 Attacks on pipelines, refineries, bridges, and so on, are among the tactics of international terrorists and local rebel groups: Nigeria and Iraq are the most telling examples to date. Similar scenarios are not unlikely wherever pipelines cross a series of countries.

The Russian–Georgian War of 2008, in which a pipeline was bombed in the early stages, was a sign of the role that the struggle for fossil energy will play in future conflicts. A resolution at the Christian Democrat congress in November 2006 showed that politicians in Germany are aware of the risks ahead and are preparing to confront them: ‘In the global age, the German economy relies more than before on free access to the world’s markets and raw materials. The Bundeswehr, as part of its task of ensuring the country’s safety, can help to secure trade routes and raw materials in the framework of international operations.’55

AENEAS, HERA, AMAZON AND FRONTEX: INDIRECT BORDER WARS56

More and more people are trying to enter Western Europe or North America illegally. Most of the refugees who want to get to Europe come from Africa across the southern maritime borders of Portugal, Spain or Italy. Other major entry points are eastern land frontiers and international airports within the EU. But at present the refugee flow is most conspicuous on the southern coasts, and that is where the five key tasks involved in securing the EU’s external borders are mainly concentrated:

- sealing the frontiers by means of technology and a police and military presence;

- transferring measures to deter would-be refugees to their countries of origin and transit;

- integrating countries of origin and transit into European measures to block refugees. A number of intergovernmental agreements have been signed that make it easier for EU border guards to operate in African coastal waters, and pressure is exerted on transit countries to crack down on illegal migrants;

- building camps for the reception and processing of refugees, both in the EU and in transit countries;

- deporting illegal migrants to their country of origin if they are not given the right to stay in Europe.57

THE MOROCCO–SPAIN ROUTE

In 2002, with EU support, the Spanish government began to establish its ‘Integrated System for External Surveillance’ (SIVE), initially concentrating on the Canary Isles and the Straits of Gibraltar,58 where refugees from Morocco had been crossing to the EU and corpses of those who failed had been regularly washed ashore. In 2005, after refugees turned to other routes, the SIVE was extended to the whole of Spain’s southern coast.59 The system consists of several dozen watchtowers, from which infrared cameras can pick out a human corpse as far as 7.5 kilometres away, and radar devices can detect a 6 x 6 metre refugee boat from a distance of 20 kilometres. In addition the Spanish coastguard carries out regular patrols with ships and helicopters.60 At first the electronic surveillance was a big success: the number of refugees reaching the shore fell sharply, as did the number of floating corpses. In 2004 a similar system was installed on the Greek islands.61 But then the refugees began to take different routes and headed more often for the Canary Isles – where in 2006, for example, 31,000 Africans landed on Fuerteventura, Tenerife and Gran Canaria. Some avoided Morocco altogether, sailing directly from Western Sahara or Mauritania and, increasingly since 2006, braving the 1,000 kilometres or more from Senegal in boats that are usually not fit for the high seas.62

In spring 2006 the Spanish government also decided to deploy surveillance satellites, and in May the French firm Spot Image and the University of Las Palmas came up with a pilot project.63 In June the British newspaper The Independent reported plans by the EU Commission to deploy unmanned drones to monitor the Mediterranean;64 the BSUAV (Border Surveillance by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) corporation subsequently devised a plan for this, under the direction of the French company Dassault Aviation.65 Italy had already bought five ‘predator drones’ from the United States in 2004, intending to use them to track irregular migrants as well as terrorists – as Leonardo Tricario, then head of the Italian air force, announced in October of the same year.66

In September and October 2005, after the SIVE had closed down the Straits of Gibraltar route, the refugee problem on the EU’s southern coast hit the headlines when hundreds of refugees in Morocco repeatedly tried to scale the border fences of the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla with home-made ladders.67 These are barbed-wire fences, three deep at some stretches, patrolled by guards with motion detectors, night vision devices and directional microphones.68 In summer 2005 preparations were under way to raise the fence around Melilla from 3.5 to 6 metres.69 Moroccan and Spanish border guards used truncheons, tear gas and rubber bullets against the rush of refugees, who fought back with sticks and stones.70 Fourteen refugees lost their lives during the events.71 As spokesmen for Médecins sans Frontières observed, the Moroccan police took 500 refugees (some of them injured) to the desert near the Algerian frontier and released them there.72 After the incidents, Morocco received EU emergency aid of €40 million to strengthen its border security.73

In a report published in September 2005, Médecins sans Frontières complained about the ‘extreme violence of the countermeasures’ used by the Moroccan border guards, but also about the EU’s sealing-off strategy. The organization estimated that there had been 6,300 fatalities on the coasts over the past ten years; the official figure of 1,40074 does not include the thousands presumed drowned at the turn of 2005– 6. (In March 2006 the Spanish government itself spoke of people ‘dying in droves’ off the Canaries.)75 ‘Torture and humiliating treatment’ added to the sufferings of the refugees. Doctors from Médecins sans Frontières reported treating a total of 9,350 migrants from sub-Saharan African countries between March 2003 and May 2005 at several places in Morocco; 2,193 of them (23.5 per cent) bore marks of torture.76

CAMPS

The building of reception and deportation camps inside and outside the EU is another part of the strategy. In February 2003, in a paper entitled New Vision for Refugees, the Blair government in Britain proposed creating a ‘worldwide network of safe havens’ (later called ‘regional protection areas’) in the vicinity of countries from which people were fleeing. In March it added a network of ‘transit processing centres’ (TPCs) outside the EU’s frontiers, designed to hold refugees applying for asylum until a decision had been taken whether to admit them or to send them back to their country of origin. These plans were backed by the governments of the Netherlands, Austria and Denmark, but the protests from sections of the European public proved too strong. Shortly afterwards, the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) submitted a variant of this model.

At an intergovernmental summit meeting held in Greece in mid-June 2003, the European Council asked the EU Commission ‘to examine ways and means to enhance the protection capacity of regions of origin’ and noted ‘that a number of Member States plan to explore ways of providing better protection for the refugees in their country of origin, in conjunction with the UNHCR’.77 In 2004 the German interior minister Otto Schily and his Italian counterpart Giuseppe Pisanu revived the plans to build camps, especially in North Africa. In October, after an informal meeting in Scheveningen, EU justice and interior ministers made it known that they planned to have ‘reception centres for asylum-seekers’ built in Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Mauritania and Libya, under the administration of the respective countries.78

There are also refugee camps in Ceuta and Melilla,79 on the Italian island of Lampedusa (where just under 2,000 refugees came ashore in 2004),80 on the Italian mainland and on various islands in eastern Greece.81 After the great surge of refugees towards the Canaries, Madrid sent a delegation to Mauritania with an offer of financial and technical assistance; thirty-five army engineers soon followed to build a camp at Nuadibu.82 Italy has extra-territorial camps in Libya and Tunisia; and in October 2004 and March 2005 the Italian authorities deported hundreds of refugees from Lampedusa to Libya.83 In Libya itself, half a million to a million people without valid papers are waiting for an opportunity to cross to Italy or Malta. In 2006 a total of 64,000 illegal immigrants were flown or trucked out of the country, quite a few of them probably released in the desert.84

The funding of extra-territorial camps and the tightening of border controls go together with political pressure on African countries to take active measures themselves against the flow of refugees.85 Between 2004 and 2006 the EU Commission allocated €120 million under its AENEAS Programme for ‘financial and technical assistance to third countries in the area of migration and asylum matters’.86 This is intended especially to cover ‘management of migratory flows, return and reintegration of migrants in their country of origin, asylum, border control, refugees and displaced people’.87

Many people use traffickers to help them cross from Africa into the territory of the EU, and the profits increase with the difficulty and expense of the journey. When an interviewer asked Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s interior minister, what was the right way to deal with refugee boats on the high seas, he replied that ‘the traffickers’ organizations must be destroyed’; only then would there be a ‘way out of the dilemma’.88

FRONTEX AGAIN

As mentioned earlier, the European Union has reacted to the increased flow of migrants by establishing a common border control, which is supposed to be the responsibility of the Frontex agency.89 Regulation (EG) 2007/2004 of the European Council, issued on 26 October 2004, provided for the establishment of a ‘European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union’. In its own words, the agency was to

- coordinate operational coordination between Member States in the field of management of external borders;

- assist Member States on training of national border guards, including the establishment of common training standards;

- carry out risk analyses;

- follow up the development of research relevant for the control and surveillance of external borders;

- assist Member States in circumstances requiring increased technical and operational assistance at external borders; and

- provide Member States with the necessary support in organizing joint return operations.90

The agency began its work in October 2005, with a budget of €6.2 million for the first year. This rose to €19.2 million for the second year, and for 2007 Frontex put the figure at €35 million91 and the German interior ministry at €42 million.92 However, this budget covers only the running of the Warsaw-based agency itself; the costs of employing and equipping border control officials fall on the Member States that make them available to Frontex.93 At the time of writing Frontex’s own administrative staff numbers 105 employees.94

On 26 April 2007, the European Parliament issued a directive for the formation of ‘Rapid Border Intervention Teams’ (RABITs), a joint initiative of the EU’s then commissioner for justice, freedom and security, Franco Frattini, and the German interior minister. These teams are supposed to be available for ‘a limited period of time’ and in ‘exceptional and urgent situations’ – that is, if ‘a Member State was faced with a mass influx of third-country nationals attempting to enter its territory illegally’.95 At first it was intended that the pool would consist of 500 to 600 officers.96 In 2007 a joint equipment pool (or ‘toolbox’) was created, whereby member states inform Frontex of the equipment they can make available to RABITs. According to the German interior ministry, this consists of ‘more than twenty aircraft, almost thirty helicopters and well over a hundred ships, plus extensive further equipment’.97

Frontex was set up as a largely autonomous supranational agency. When some Free Democrat deputies enquired about its accountability, the German government replied on 13 April 2007: ‘The executive director of Frontex [the Finnish brigadier-general Illka Laitinen] has a duty to keep the governing board of Frontex informed. The European Parliament or Council may ask the executive director to provide a report about the performance of his duties. Frontex does not have an obligation to provide information to Member States.’98 Frontex itself emphasizes that its activity is ‘intelligence driven’99 – which means that it cooperates and pools information with the secret services of member states. Some of the first Frontex deployments in 2006 took place in collaboration with EUROPOL.100

According to its report for 2006, the agency directed a total of fifteen ‘operations’. In June and July, for example, it drew on border guards from Austria, Italy, Poland and Britain to strengthen controls on the Greek–Turkish frontier and the Greek coasts, apprehending a total of 422 illegal migrants. But Frontex remains discreet about the details of its local work. The fifteen operations included ‘Hera I’ and ‘Hera II’ in the Canary Isles, which became the flash points for illegal immigration from Africa after the clampdown on Spain’s southern coast and in the Spanish enclaves in Morocco. In the framework of Hera I, international experts gave the Canary Isles authorities key assistance in determining the citizenship of the refugees they apprehended.

With Hera II, beginning on 11 August 2006, Frontex took on direct responsibilities for maritime surveillance and border control. Along with the Portuguese coastguard, it was reported to be using one Portuguese and one Italian ship, and one Italian and one Finnish aircraft. For the first time, activities were organized in Senegalese and Mauritanian territorial waters, in collaboration with the local authorities. During its nine weeks, the operation apprehended 3,887 refugees on fifty-seven fishing boats, and another 5,000 were prevented on the African mainland from taking to the high seas. A total of seven Schengen countries took part.101

In February 2007 Frontex got Hera III under way: this involved questioning refugees in the Canaries about the routes they had taken there and then attempting to cut those routes as close as possible to the African coast.102 In 2006 and 2007, Frontex’s ‘Amazon’ and ‘Amazon II’ operations gave it experience on the European mainland, checking for illegal immigrants at the international airports of Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Lisbon, Milan, Madrid, Paris and Rome. Twenty-nine border officials from seven EU countries vetted 2,161 people during the seventeen-day exercise.103 Since May 2007 Frontex has been coordinating joint patrols by border police forces in the Mediterranean.104

ILLEGAL ALIENS

The US has a frontier of 8,891 kilometres with Canada and 3,200 kilometres with Mexico. Although Washington and Ottawa cooperate on immigration and border control, the US northern frontier poses relatively minor problems, since Canada’s geographical position makes it difficult for illegal immigrants to reach. Current estimates put the number of people living illegally in Canada at approximately 200,000.105 In the last fifteen years, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has led to progressively tighter control of the US–Mexican frontier, with a doubling of patrols and the installation of fences and walls, especially in the vicinity of transport hubs and cities, where illegal immigrants can easily blend into the crowd. In the late summer of 2006, for example, a triple steel wall 4.5 metres high was erected around the busy highway linking San Diego with the Mexican city of Tijuana. There are similar structures in Arizona and Texas.106 Each year several hundred people die in an attempt to enter the USA illegally from Mexico,107 and the dangers are increasing as border security measures become tighter.108 Among the causes of death are snake and insect bites, drowning, cactus wounds, accidents and thirst.109

In response to the terror attacks of 11 September 2011, President Bush created a special office in the White House to develop a ‘National Strategy for Homeland Security’, and in November 2002 the resulting Department of Homeland Security (DHS) took over responsibility for border protection. The strategy paper submitted in July had already shown a tendency to highlight the terrorist threat in border control and, at least officially, to organize around that priority. Here is a typical quote: ‘America historically has relied heavily on two vast oceans and two friendly neighbors for border security, and on the private sector for most forms of domestic transportation security. The increasing mobility and destructive potential of modern terrorism has required the United States to rethink and renovate fundamentally its systems for border and transportation security.’110 As early as October 2001, the so-called Patriot Act had made it easier to hold non-citizens for investigation and to deport immigrants.111

The Department for Homeland Security also took over responsibility for the US Coastguard and the newly created ‘US Customs and Border Protection’ (CBP).112 Since then controls have also been tightened on legal entry. Visa-free travel – from EU countries, for example – is now possible only with machine-readable passports, and fingerprints or photos are taken at the point of entry. In future people intending to enter the United States will have to register online forty-eight hours in advance. The German foreign office already advises travellers to be at the departure airport at least three hours before take-off in order to allow time for security clearance.113 The USA is pioneering the collection and recording of biometric data: travellers from visa-free countries will soon have prints taken of all ten fingers; and a DHS representative has announced that future checks may include retina scans. The collected data will be fed into a central bank, to which the FBI and the CIA will have access.114

The privatization of security services is an interesting aspect of this. In 2006 the US government spent $545 per head of the population on homeland security, and in the 22-month period ending in August 2006 awarded more than 100,000 contracts to private firms for security functions.115 Border collaboration between the US and Canada intensified after September 11, with the compiling of joint ‘passenger analysis lists’, and in December a ‘Smart Border Declaration’ provided for increased exchange of information (‘Project Northstar’). The Royal Canadian Mounted Police now has access to the FBI’s fingerprint database, and each country’s data about refugees and asylum-seekers is shared and closely monitored.116

The main responsibility for border control lies with the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which began work in March 2003. With a staff of 42,000, including 18,000 officers at the 325 frontier posts at airports, seaports and land crossings and a further 11,000 for border surveillance, the CBP reports having a fleet of at least 8,000 motor vehicles, 260 aircraft and 200 ships.117 Since 2005 two unmanned drones have been patrolling Arizona, and by the end of 2008 four more were due to come into service to monitor stretches of coast and parts of the border with Canada.118 On an average day nearly 1.2 million people legally cross the US borders, 870 are turned away at entry points, and just under 3,500 are caught trying to evade checkpoints (‘illegal aliens’). For every successful attempt to enter illegally, there are eight failed attempts.119

November 2005 saw the ‘Secure Border Initiative’ (SBI) come into force – a brainchild of the secretary of homeland security, Michael Chertoff. According to the CBP, this is designed to tighten not only border controls but also the implementation of customs and immigration procedures, and to oversee the official ‘Temporary Worker Program’. A ‘critical part’ of the SBI is ‘SBInet’, a border modernization programme reliant on high-tech surveillance and communication.120