Chapter 1

Music as a Mediated Object, Music as a Medium: Towards a Media Ecological View of Congregational Music

Tom Wagner

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to view congregational music from the perspective of media ecology – that is, as something that is both a media object and a form of media.1 Consider the following vignette, drawn from my PhD fieldwork at the London branch of the Australian transnational network church Hillsong Church (Wagner 2014a):

As I exit the Tottenham Court Road tube station on a brisk Sunday afternoon in early 2012, a giant golden statue of Freddy Mercury greets me from atop the entrance to the Dominion Theatre in London’s West End. The statue has invited theatregoers to experience Ben Elton’s We Will Rock You musical six nights a week for over a decade.2 On Sundays, though, Mercury bears witness to a different dominion – the dominion of God – as Hillsong London, which has called the theatre home since 2005, transforms the theatre into a church. I pass under the Hillsong London signs hung overhead and through the glass doors held open by fresh-faced greeters in jackets emblazoned with the Hillsong logo. Inside, I am confronted by a flat screen television playing a video loop advertising Hillsong’s upcoming European conference. Images of the worship band flash across the screen. The lobby’s soundscape is a hubbub of friends greeting each other, Hillsong tourists snapping selfies and Hillsong worship music piped in over the theatre’s public address system.

After making small talk with some acquaintances, I climb the steps to the foyer, grab a cup of coffee and proceed into the theatre to find a seat. Below me, dry ice drifts across a proscenium stage bathed in deep blue and purple lights. Strains of ambient music can be heard in the background. The screen behind the stage reads ‘Welcome Home’. At 3:30 on the dot, the theatre lights drop. Images of London, church members and scripture flash across the screen. The worship band takes the stage, its sound seamlessly cross-faded into the front of house mix by sound engineers at the rear of the auditorium. During the next hour and a half, music is almost constantly present, shaping and informing the experience of corporate worship.

The service, which is simulcasted to Hillsong London’s Surrey campus, concludes at almost precisely 5pm with an upbeat number from Hillsong’s latest CD. Back at the foyer’s resource centre, I peruse a range of Hillsong CDs, DVDs and books on offer. These are also available on the Internet through Amazon, iTunes or the church’s publishing company, Hillsong Music Australia. Furthermore, on the Internet I can watch Hillsong music videos on YouTube, or connect to other Hillsong churches through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or the church’s website.

The worship service described above is easily recognizable to anyone familiar with highly mediatized, networked evangelical Christianity (for example, Campbell 2013, 2015; Coleman 2000). It is an expression of faith in what media theorist Henry Jenkins calls ‘convergence culture’, where ‘every important story gets told, every brand gets sold, and every consumer gets courted across multiple media platforms’ (2006, 3). For Jenkins, convergence culture is an always-evolving set of logics and practices that shape how media operates within media environments. They are best understood as the relationship among three concepts: convergence, participatory culture and collective intelligence (Jenkins 2006, 2).

The concept of convergence has been around since 1983, when Ithiel de Sola Pool’s Technologies of Freedom proposed that one day a single, integrated common carrier would meet all media needs. In the mid-1980s, new media technologies supporting multiple forms of the same content emerged. Around the same time, cross-media ownership became the norm. These two factors created the conditions and the imperatives for convergence (Jenkins 2006, 11). Convergence has since been noted in a variety of social, cultural, technological and industrial spheres. For example, Habermas (1992) and Sennett (2003) noted the convergence of the public and private (although they saw it more as transformation of the former into the latter), a theme that has recently been taken up with respect to the Internet (for example, Graham and Khosravi 2002; Rettberg 2008). Others have noted the convergence of producer and consumer (Ritzer and Jurgenson 2010; Toffler 1980; Xie et al. 2008), and of the organizational and communicative techniques of religious and business organizations (Einstein 2008; Twitchell 2004, 2007). Convergence culture is located at the nexus of these changes.

Participatory culture is one in which the lines between producer and consumer are blurred, where information is no longer distributed but rather circulated in networks that (re)shape, (re)make and (re)mix it to serve the personal and collective interests of its participants (Jenkins, Ford and Green 2013, 2). Participatory culture is therefore one in which ‘consumers are encouraged to seek out new information and make connections’ (Jenkins 2006, 3). However, participation depends on resources, knowledge and access that are still mostly controlled by corporations, as opposed to individuals or groups of consumers; thus participation is asymmetric (Jenkins 2006, 3). This does not mean, however, that corporations dominate convergence culture.3 Indeed, the personal agency that constitutes networks is increasingly valuable to industry and therefore the way that collective meaning-making occurs within networks is beginning to change how institutions operate. Collective intelligence, then, refers to the way in which consumption can be understood as a collective communicative process that is an ‘alternative source of media power’ (Jenkins 2006, 4).

Media ecology is the study of how dominant forms of communication in a media environment affect the ways people relate to the world. A media ecology view of congregational music, especially at transnational megachurches such as Hillsong, considers how music functions relative to the dominant communicative norms and cultural logics of the networked environments of convergence culture.4 In this chapter, I begin with the assumption that the ‘dominant’ mode of cultural communication for churches that operate in convergence culture is marketing. However, my task is neither to lament it as somehow ‘killing’ religion nor celebrate it as an evangelical ‘magic bullet’; both of these perspectives are well documented. Rather, I suggest that marketing should be understood as communication bound up with the socio-cultural practices and logics of highly mediatized (and materialized) convergence culture. Furthermore, marketing should be understood as a social practice that is simultaneously sensorial, symbolic and generative. This foregrounds both how and why people engage with media as they work to realize spiritual ambitions in their everyday lives.

This chapter is presented in three parts. Part 1 introduces the core ideas that make media ecology a useful theoretical perspective from which to approach congregational music. To understand how congregational music functions as both a media object and as a medium music, media and religious experience must be viewed as embedded in a matrix of socio-cultural life that is at once sensorial, symbolic and generative. Part 2 presents Hillsong Church’s annual  (cross equals love) Easter media campaign. Consistent with the practices and logics of convergence culture, the campaign utilizes cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. Part 3 situates the

(cross equals love) Easter media campaign. Consistent with the practices and logics of convergence culture, the campaign utilizes cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. Part 3 situates the  campaign’s use of music in a larger socio-cultural matrix where music is part of a marketing gestalt. I suggest that the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depends on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. Following Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’ (for example, Meyer 2008, 2011), I propose that a media ecology view of congregational music sees marketing as inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience in convergence culture.

campaign’s use of music in a larger socio-cultural matrix where music is part of a marketing gestalt. I suggest that the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depends on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. Following Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’ (for example, Meyer 2008, 2011), I propose that a media ecology view of congregational music sees marketing as inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience in convergence culture.

Part 1 – Congregational Music: A Mediated Object and Medium

Since congregational music is both a (religiously)-mediated object and (religious)-medium, it should be approached from a theoretical perspective that views religion and media as embedded in a matrix of cultural life. Peter Horsfield and Paul Teusner suggest that:

Every expression of Christianity, every experience of spirituality, every Christian idea, is a mediated phenomenon. It is mediated in its generation, in its construction and in its dissemination. In the process of its mediation, it is incarnated with particular grammar, logic, validations, sensibilities, frames, industrial requirements, cultural associations and structures, power relationships, opportunities and limitations that give it nuances that contest with other mediations of the same faith (though deciding which different mediations are the ‘same’ faith or a different faith is in itself a political exercise). (Horsfield and Teusner 2007, 279)

Horsfield and Teusner are essentially advocating a media ecology view. Media ecology views media as environments and environments as media (Lum 2006, 31). It arises from early twentieth century ecological concerns about the interrelationship between natural and built environments, our senses and human culture (for example, Geddes 1915; Mumford 1938, 1961) as well as linguistic and cultural investigations into the way symbolic systems shape how we interact with the world (for example, Langer (1942) and Whorf (1956)) (Lum 2006, 28). It takes into account functional, interpretative, cultural and critical theories. It looks at language, message and meaning, as well as technology and contexts, and examines the interaction of political, economic, religious and cultural norms. In short, media ecology attempts to construct a holistic understanding of the role media play in how we become human.

Casey Man Kong Lum’s (2006) discussion of media ecology’s view of the relationship between the sensorial and symbolic is a useful starting point. From the media ecology perspective, the sensorial and symbolic do not exist separately; furthermore, no medium stands alone, but is always part of a multi-media environment (30–31). In other words, although we may examine the sensorial-symbolic implications of a given medium (such as music) in abstraction, in reality its role is always contingent upon interactions with other media in a dynamic system.

Viewing media as sensorial environments has physiological-perceptual implications (Lum 2006, 28–9). We experience ourselves relative to the constant flow of information from our external world and our internal states. According to McLuhan (2001), every medium engages the user’s senses differently, and thus embodies a unique set of sensory characteristics. For example, reading primarily engages our visual senses, while listening to the radio primarily engages our auditory capabilities. McLuhan’s student, Walter Ong (2012), suggested that a society’s dominant communication medium determines which of its people’s senses are most acute, and this has far-reaching cultural implications because it influences the way people comprehend the world around them. Thus, media as sensorial environments are profound influences on the ways we experience the world and ourselves.

Media can also be thought of as symbolic environments (Lum 2006, 29–30). From this perspective, every medium is ‘systemically constituted by a unique set of codes and syntax’ (Lum 2006, 29). For example, the use of English as a communication medium requires an understanding of (and facility with) its vocabulary (that is, its symbols and their assigned meanings) as well as its grammar (that is, its syntax and rules that govern the construction of meaning) (Lum 2006, 29). Similarly, the way congregational music is ‘understood’ requires familiarity with the cultural codes that give it meaning in a given context. As Moberg (this volume) points out, this is complicated because the way music is culturally coded is always already intertextual. Furthermore, the relative mastery of these codes, especially in the actual making of music, has implications for who can participate and how (see Goddard, this volume).

What emerges from this discussion is that the sensorial and the symbolic are mutually generative processes. Media scholars traditionally talk about media in terms of delivery devices. From this view, technologies mediate but are not themselves media. However, this ignores how the symbolic structures of socio-cultural environments influence the role of technologies in the production of the cultural. Seeing environments as media clarifies this. For example, a church is a multi-media environment that employs its own vocabulary and rules that shape how its participants conduct themselves and relate to one another internally and externally. Participants’ actions both affect and are affected by, and are thus generative of, the socio-cultural field of communication that is the environment; therefore, the environment itself can be thought of as medium (Lum 2006, 31–2).

A media ecology approach to congregational music can thus be described as (following Musa and Ahamdu 2012) ‘techno-cultural’ in that religion, music, technology and culture are treated as mutually transformative parts of a media environment. As noted, a central tenet of media ecology is that our thinking and behaviour changes in relation to the dominant communication technologies of the media environment. Here, the term ‘technology’ should be understood in the broadest sense, as ‘the total knowledge and skills available to any human society’.5 This includes technologies of storage, retrieval and (re)production of information. Musical examples of this might include the human body, printed scores, microphones or mp3s (Frith 1996, 226–45). ‘Technology’ should also include Foucauldian ‘technologies of self’ that configure and govern the human subject in socio-cultural ‘matrices of reason’ (Foucault 1988). Technologies evolve, but the introduction of new technologies (in whatever form) does not necessarily mean previous ones will be discarded or forgotten. Rather, new technologies reorient the way their predecessors and other technologies are used and valued in relation to one another, culture and society. Furthermore, they reorient the ideologies, values and structures of the culture itself. When thinking about congregational music from a media ecology perspective, then, we should view it as both a mediated object and a medium, attending to the socio-cultural practices and logics of the media environment of which it is part. For churches such as Hillsong Church, this environment is convergence culture.

Australia’s Hillsong Church offers a rich picture of congregational music’s role in a convergent media environment. Hillsong’s media ecosystem is a complex network of branded communication platforms that afford participants different, mutually informing ways of knowing (Wagner 2014a). This network of platforms includes not just old and new media technologies, but also commodities, people, places (both physical and virtual) and institutions (Pine and Gilmore 2011). For example, the church communicates through print media such as the seat drops in services, books by its founders Brian and Bobbie Houston as well as lifestyle magazines. Demographically targeted CDs and DVDs circulate both sonic and visual tropes that are repeated, recombined and elaborated as elements of worship services. Hillsong’s pastors and worship leaders are also important parts of the church’s message: they function as both local church ministers and mediated celebrities whose images and personalities are co-branded with that of the church (Riches and Wagner 2012; Wagner 2014b). Additionally, Hillsong maintains a network of institutions including name-brand churches in major cities around the world, its ‘family’ of affiliated churches, and Hillsong College in Baulkham Hills.6 Finally, an important part of Hillsong’s media ecology is its online infrastructure of both official and unofficial websites and social media. These platforms are almost always connected by sonic, textual or visual references to Hillsong’s music; thus, the music is often the connective tissue holding its message together.

Hillsong’s organization and communication practices mirror the continued adoption of ‘secular’ business models by organizations such as churches, universities and other non-profit organizations (for example, Dauvergne and LeBaron 2014; Einstein 2008; Twitchell 2004). These organizations have different audiences who interact through different media. As Henrion and Parkin noted in their 1967 manifesto Design Coordination and Public Image:

A corporation has many points of contact with various groups of people. It has premises, works, products, packaging, stationery, forms, vehicles, publications and uniforms, as well as the usual kind of promotional activities. These things are seen by customers, agents, suppliers, financiers, shareholders, competitors, the press, and the general public, as well as its own staff. The people in these groups build up their idea of the corporation from what they see and experience of it. An image is therefore an intangible and essentially complicated thing, involving the effect of many and varied factors on many and varied people with many and varied interests. (Henrion and Parkin 1967, 7, in Moor 2007, 30–31)

The goal of corporate branding is essentially to get different stakeholders to ‘buy in’ to the ethos and values of an organization, to ‘live the brand’ as it were. This is especially important for transnational organizations because their messages must be both globally coherent and locally adaptable, which is to say understandable and useable by diverse audiences in diverse contexts (Henrion and Parkin 1967; Moor 2007; Olins 1978; Pilditch 1970). Corporate branding thus takes on special significance for religious organizations for two reasons. First, the appearance of a coherent message is a necessity for religious movements like evangelical Christianity that are built on the idea of a central, unchanging Truth. Second, because church employees are usually also congregation members, they are ‘touchpoints’ for both internal and external stakeholders. For example, Hillsong’s songwriters and worship leaders are members of the church, so their songs are seen (and promoted) as authentic expressions of the congregation as a whole (Wagner 2014a, 2014b).

Convergent marketing practices are increasingly seen as essential features of corporate branding (Stuart and Jones 2004; Wind and Mahajan 2001, 2002). As marketing has migrated online, it has expanded to include a variety of crowdsourcing activities such as not-for-profit development of open-source software, very-much-for-profit development of new products for private companies, and campaigns that encourage customers to create web content in support of products. While there is considerable disagreement over who benefits – and in what manner – from these new forms of participation, it is widely recognized that multiple types of value are derived from stakeholders’ agency.7

Part 2 – Hillsong Church’s Annual  (Cross equals Love) Easter Media Campaign

(Cross equals Love) Easter Media Campaign

An excellent example of this leveraging of agency is the ‘ ’, an annual three-week campaign that promotes Hillsong’s Easter message. Originally conceived in 2008 by Hillsong Art Director Jay Argaet and Worship Pastor Joel Houston as ‘a simple way to explain the Gospel’ (email to author, 30 April 2014), the

’, an annual three-week campaign that promotes Hillsong’s Easter message. Originally conceived in 2008 by Hillsong Art Director Jay Argaet and Worship Pastor Joel Houston as ‘a simple way to explain the Gospel’ (email to author, 30 April 2014), the  concept has evolved from a largely local campaign to a global Christian ‘meme’, as it has been adapted to the practices and logics of its media environment. Piloted at Hillsong’s Australian churches, the initial campaign employed a ‘random acts of kindness’ model similar to that popularized by Oprah Winfrey. For example, a participant might surreptitiously pay for someone’s coffee in a coffee shop. When the person on the receiving end of this gesture would later attempt to pay, he or she would be presented with a card that read (in the 2011 version of the campaign): ‘This is Love Find out why? tiny.cc/theXchange’ (Grimmer and Grimmer 2011). Later versions of the campaign fused Oprah with Ashton Kutcher, as participants set out to ‘Love Punk’ people.8 In this version, participants would leave a five- or ten-dollar bill in a public place attached to a handwritten note that might, for example, invite the lucky discoverer of the money to visit the campaign’s website.9 These interactions were covertly filmed and then posted to YouTube and the campaign’s Tumblr page.10

concept has evolved from a largely local campaign to a global Christian ‘meme’, as it has been adapted to the practices and logics of its media environment. Piloted at Hillsong’s Australian churches, the initial campaign employed a ‘random acts of kindness’ model similar to that popularized by Oprah Winfrey. For example, a participant might surreptitiously pay for someone’s coffee in a coffee shop. When the person on the receiving end of this gesture would later attempt to pay, he or she would be presented with a card that read (in the 2011 version of the campaign): ‘This is Love Find out why? tiny.cc/theXchange’ (Grimmer and Grimmer 2011). Later versions of the campaign fused Oprah with Ashton Kutcher, as participants set out to ‘Love Punk’ people.8 In this version, participants would leave a five- or ten-dollar bill in a public place attached to a handwritten note that might, for example, invite the lucky discoverer of the money to visit the campaign’s website.9 These interactions were covertly filmed and then posted to YouTube and the campaign’s Tumblr page.10

Early versions of the  campaign were mostly limited to Hillsong’s Australian churches. However, in 2012, the campaign went global. This is the same year that the

campaign were mostly limited to Hillsong’s Australian churches. However, in 2012, the campaign went global. This is the same year that the  symbol became the centrepiece of the Easter campaign, along with the hashtag #crossequalslove. Participants were encouraged to create their own versions of the

symbol became the centrepiece of the Easter campaign, along with the hashtag #crossequalslove. Participants were encouraged to create their own versions of the  symbol in unexpected ways and in unexpected places, and to share images of their creations on social media with the hashtag. For example, during the 2013 campaign, Hillsong’s City Campus youth group stacked blue and red milk crates in the shape of

symbol in unexpected ways and in unexpected places, and to share images of their creations on social media with the hashtag. For example, during the 2013 campaign, Hillsong’s City Campus youth group stacked blue and red milk crates in the shape of  in Sydney’s Hyde Park.11 Other popular media included foodstuffs (for example,

in Sydney’s Hyde Park.11 Other popular media included foodstuffs (for example,  drawn in jam on toast) and jewellery.12 Images of these actions were posted, shared, tweeted and retweeted with the #crossequalslove hashtag.

drawn in jam on toast) and jewellery.12 Images of these actions were posted, shared, tweeted and retweeted with the #crossequalslove hashtag.

The explosion in popularity of the  campaign can be analysed in terms of the convergent practices and logics it leverages. It is tempting to describe the campaign as having ‘gone viral’; however, as Jenkins, Ford and Green (2013) point out, this expression implies that the message ‘infects’ passive hosts when in reality transmission occurs when media is appropriated, manipulated and put to use by active participants who have conscious goals. By proposing the term ‘spreadable’, Jenkins, Ford and Green highlight the multiple ways networked actors circulate media and ideas. An important feature of media circulation in convergent environments is that only a small number of participants create content (such as the contributions by City Campus or the jam-on-toast artists). However, a large number will share that content in their social networks; therefore spreadable content needs to be easily (re)creatable, but more importantly easily sharable.

campaign can be analysed in terms of the convergent practices and logics it leverages. It is tempting to describe the campaign as having ‘gone viral’; however, as Jenkins, Ford and Green (2013) point out, this expression implies that the message ‘infects’ passive hosts when in reality transmission occurs when media is appropriated, manipulated and put to use by active participants who have conscious goals. By proposing the term ‘spreadable’, Jenkins, Ford and Green highlight the multiple ways networked actors circulate media and ideas. An important feature of media circulation in convergent environments is that only a small number of participants create content (such as the contributions by City Campus or the jam-on-toast artists). However, a large number will share that content in their social networks; therefore spreadable content needs to be easily (re)creatable, but more importantly easily sharable.

With the easily spreadable  symbol, Hillsong was able to leverage convergence and the media-ethos of participatory culture. As Jay Argaet noted in an email to me:

symbol, Hillsong was able to leverage convergence and the media-ethos of participatory culture. As Jay Argaet noted in an email to me:

I guess what is the point of difference for this campaign [from previous years] is we utilized marketing in a way that really worked. We understood that there is [a] two-way approach in marketing Easter – Internally to equip the church to be bringers and interact with the campaign and Externally to inspire people who are yet to experience Jesus to find about Him. (Email interview with author, 30 April 2014, emphasis added)

Two important ideas are expressed in this email. First (as noted earlier), ‘two-way’ marketing is important for communicating to stakeholders both within and outside of an organization. Second, convergent marketing encourages ‘two-way’ communication between an organization and its stakeholders. As also noted earlier, while there is much disagreement concerning the pros and cons of Web 2.0 marketing, there is broad agreement that the productive agency of networked communities is ‘valuable’. Indeed, all of the participants I interviewed during the 2013 campaign at Hillsong London described their involvement as personally valuable. For example, one 18-year-old woman told me that: ‘It [participating in the  campaign] was really good! It helped me understand how deep Jesus’ love for me is … One of my friends at uni really liked the pictures and she’s going to come [to church] next Sunday!’ (interview with author, 1 April 2013).

campaign] was really good! It helped me understand how deep Jesus’ love for me is … One of my friends at uni really liked the pictures and she’s going to come [to church] next Sunday!’ (interview with author, 1 April 2013).

This young woman described her participation as personally valuable in terms of both ‘inward’- and ‘outward’-facing evangelism. In line with the evangelical emphasis on a personal journey, she emphasized the ‘educational’ aspects of the campaign. This teaching came not so much from sharing the  , but from the associated discourse in the form of preaching topics, blog posts and song lyrics (discussed in the next section). She also emphasized that the campaign helped her spread the Gospel by giving her a way to engage a friend. I have suggested elsewhere that by positioning its music as an evangelical resource, Hillsong imbues it and, by extension those who use it, with the evangelical power of the Holy Spirit (Wagner 2014b). Similarly, I suggest that the ‘two-way’ marketing of the

, but from the associated discourse in the form of preaching topics, blog posts and song lyrics (discussed in the next section). She also emphasized that the campaign helped her spread the Gospel by giving her a way to engage a friend. I have suggested elsewhere that by positioning its music as an evangelical resource, Hillsong imbues it and, by extension those who use it, with the evangelical power of the Holy Spirit (Wagner 2014b). Similarly, I suggest that the ‘two-way’ marketing of the  campaign afforded a real, immediate experience of God through its participants’ own agency.

campaign afforded a real, immediate experience of God through its participants’ own agency.

Yet where is the music in all of this? The  would be just as ‘spreadable’ without any musical associations. This is where Hillsong’s profoundly musical identity comes into play, illuminating the ways meaning and experience coalesce in convergence culture. In the next section, I suggest that while not essential to the fecundity (spreadability) of the campaign’s message, music was essential to its fidelity (focus).

would be just as ‘spreadable’ without any musical associations. This is where Hillsong’s profoundly musical identity comes into play, illuminating the ways meaning and experience coalesce in convergence culture. In the next section, I suggest that while not essential to the fecundity (spreadability) of the campaign’s message, music was essential to its fidelity (focus).

Part 3 – Music, Marketing and Religious Experience in Material Culture

Hillsong’s cross-platform communication is a self-referential gestalt: any communication associated with the church draws on and feeds back into its overall ‘brand’ identity. Because the church’s identity is inextricable from its music (Riches and Wagner 2012; Wagner 2014a), even ‘non-musical’ symbols such as  will garner some kind of musical association. This is evident in Hillsong’s communication strategy, which illustrates the ways music, marketing and meaning coalesce in convergence culture (for example, Carah 2010, Taylor 2012). As the number of media platforms has grown, music has moved from a largely stand-alone medium to part of a communicative matrix of people, places, commodities and industries (Taylor 2012). Today, music’s meaning is often realized as part of a larger branded ecosystem in a culture where participants ‘expect’ songs to be associated with, for example, the release of a new movie, a product rollout, spin-offs and brand extensions.

will garner some kind of musical association. This is evident in Hillsong’s communication strategy, which illustrates the ways music, marketing and meaning coalesce in convergence culture (for example, Carah 2010, Taylor 2012). As the number of media platforms has grown, music has moved from a largely stand-alone medium to part of a communicative matrix of people, places, commodities and industries (Taylor 2012). Today, music’s meaning is often realized as part of a larger branded ecosystem in a culture where participants ‘expect’ songs to be associated with, for example, the release of a new movie, a product rollout, spin-offs and brand extensions.

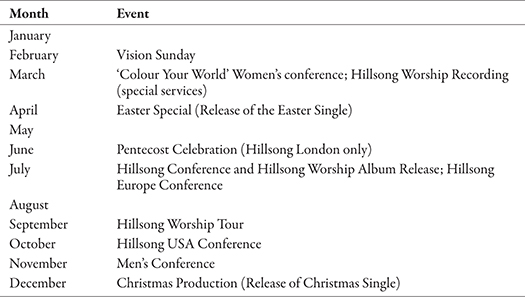

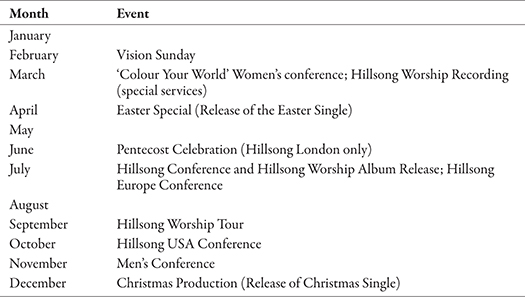

Hillsong operates in a (Christian) material culture where commodities are an essential part of religious experience (for example, Hendershot 2004; King 2010; McDannell 1995); therefore, music production, distribution and marketing concerns are essential to meaning-making. This being the case, its music production calendar can be considered a ‘liturgical calendar’ (Riches 2010: 145–7). Historically, the form and content of church services (for example, rituals, hymns and bible readings) were dictated by a liturgy that varied by time of year, with special attention to holiday seasons. At Hillsong churches, the traditional holiday celebrations of Easter and Christmas are interwoven with its own major events that revolve around the recording and release of its music. This means that the content of services at any point in the year is at least partially dictated by production and marketing concerns that are strategically integrated with its preached message. Table 1.1 below is a simplified version of Hillsong’s music production calendar.

Table 1.1 Hillsong LIVE’s production activities are coordinated with holidays and major church events (based on chart in Riches 2010, 146)

A year in the life of Hillsong Church begins on the first Sunday in February, dubbed ‘Vision Sunday’. On this day, a video outlining church founder Brian Houston’s vision for the coming year is shown in every service at every Hillsong church around the world. This vision is presented in short, dramatic scenes that introduce the central concepts and associated visual material (for example, the  symbol) that will be the building blocks of the church’s message in the coming year. To maintain the coherence of the message, the new material is interwoven with themes from previous years. For example, early depictions of

symbol) that will be the building blocks of the church’s message in the coming year. To maintain the coherence of the message, the new material is interwoven with themes from previous years. For example, early depictions of  were based on 2011’s theme: The Scarlet Thread.13

were based on 2011’s theme: The Scarlet Thread.13

Following Vision Sunday, the next major event of the year is the recording of the Hillsong Worship album, which is one of the two annual musical releases that anchor Hillsong’s brand.14 Each March, a day of services is set aside specifically for a new album’s recording. Because the album is recorded ‘live’, the songs have all been field tested and taught to the congregation in the preceding months. The new album is then heavily promoted in the run-up to its release at Hillsong’s July conference. From July onwards, songs from the newly released album are put into ‘heavy rotation’ in services, as the songs and the visual material associated with them are interwoven with topical preaching derived from Vision Sunday.15 Hillsong’s message thus emerges from a self-referential, cyclical communications strategy of which the production and distribution of its musical product is an important element.

This convergence of music, marketing and religious experience is evident in the 2013 and 2014  campaigns, both of which were kicked off with the release of an Easter single (‘Man of Sorrows’ and ‘Calvary’, respectively). Hillsong views marketing as an evangelical activity (Riches 2010) and music as an evangelical ‘resource’ (Riches 2010; Wagner 2014a). As Jay Argaet notes: ‘The whole motivation around releasing a free song at Easter is to help the churches have a fresh song at Easter time … So it is something we have aimed to do every year is also release a free song in the campaign to bless the churches’ (email interview with author, 30 April 2014).

campaigns, both of which were kicked off with the release of an Easter single (‘Man of Sorrows’ and ‘Calvary’, respectively). Hillsong views marketing as an evangelical activity (Riches 2010) and music as an evangelical ‘resource’ (Riches 2010; Wagner 2014a). As Jay Argaet notes: ‘The whole motivation around releasing a free song at Easter is to help the churches have a fresh song at Easter time … So it is something we have aimed to do every year is also release a free song in the campaign to bless the churches’ (email interview with author, 30 April 2014).

The Easter singles were also presented as resources for advertising the albums of which they were part (each was the first release of its respective annual summer album), and as material for other communicative media, such as preaching and blog posts. For example, in a 17 April 2014 post, on the Hillsong blog, Hillsong Collected, Pastor Brian Houston used lyrics from ‘Calvary’ and ‘Heaven and Earth’ – both on the 2014 Hillsong Worship album No Other Name – as his starting point (Houston 2014).

How, then, do we think about the role of congregational music in media ecology terms? What I have tried to highlight in this case study is that media, marketing and religious experience are reciprocally related through socio-cultural practices and logics. In convergence culture, the ways that participants engage with congregational music are always ‘networked’ in an overall socio-cultural matrix that is simultaneously sensorial, symbolic and generative. I suggest that the religious experiences of the  campaign’s participants were more than simply informed by the marketing: they were dependent on it. To further clarify, I turn to anthropologist Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’.

campaign’s participants were more than simply informed by the marketing: they were dependent on it. To further clarify, I turn to anthropologist Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’.

Meyer’s notion of sensational forms seeks to account for what she calls the ‘paradox of immediacy’. As she notes, ‘the more we recognize media as being central to socio-cultural life, the less we can offer a straight-forward answer to the question what a medium is’ (2011, 25). As an immediate experience is repeatedly realized through a medium – for example, the transcendent experience of the Holy Ghost in pentecostal practice through worship music – the medium begins to transcend its materiality, becoming ‘invisible’ through social processes. Furthermore, as the medium is repeatedly used as a vehicle of transcendence, it becomes imbued with spiritual efficacy, or as she puts it, authorized:

It is via particular modes of address, established modes of communication, and authorized religious ideas and practices that believers are called to get in touch with the divine, and each other. Sensational forms do not only convey particular ways of ‘making sense’ but concomitantly tune the senses and induce specific sensations, thereby rendering the divine sense-able, and triggering particular religious experiences. (Meyer 2008, 129)

The paradox here is that the more the medium becomes ‘invisible’, which is to say spiritually efficacious, the more its presence is needed for the realization of the experience, thus making it more ‘visible’. Following Meyer, I suggest that, from a media ecology view, the marketing of the  campaign acts in the same manner. The repeated communication act is a necessary precondition for religious experience; ‘form’ and ‘content’ do not exist in opposition; rather, ‘form is necessary for content to be conveyed’ (Meyer 2011, 30). The marketing of the

campaign acts in the same manner. The repeated communication act is a necessary precondition for religious experience; ‘form’ and ‘content’ do not exist in opposition; rather, ‘form is necessary for content to be conveyed’ (Meyer 2011, 30). The marketing of the  campaign was ‘formulaic’, employing familiar communicative practices and logics and affording participants ways to actively engage in the immediate experience of God within a recognizable framework.

campaign was ‘formulaic’, employing familiar communicative practices and logics and affording participants ways to actively engage in the immediate experience of God within a recognizable framework.

Conclusion

As ethnomusicologist John Blacking pointed out, music is both a modelling system of human thought and a part of the infrastructure of human life. Making music is both reflexive and generative, a cultural system and a human capability; thus, it is a special kind of social action with important consequences for other social actions (Blacking 1995, 223). A media ecological view of congregational music attempts to be, as far as possible, holistic. It takes into account how various forms of communication influence our moral, physical, social, intellectual and spiritual development. It understands congregational music as a communication environment that affords certain modes of human relationships according to socio-cultural practices and logics. It also understands congregational music as a technology, in the widest sense of the term, which influences values, religious sensitivities and basic theological understandings (Forsberg 2009).

Hillsong Church’s annual  campaign utilized cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. In particular, it leveraged the practices and logics of convergence culture that afford participants the ‘two-way’ communication and participation that they deem valuable and are necessary for the immediate religious experience. The campaign was built around the easily spreadable

campaign utilized cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. In particular, it leveraged the practices and logics of convergence culture that afford participants the ‘two-way’ communication and participation that they deem valuable and are necessary for the immediate religious experience. The campaign was built around the easily spreadable  symbol, but the message was very much rooted in Hillsong’s overall musical identity. Thus the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depended on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. In other words, convergent marketing was inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience that the campaign afforded.

symbol, but the message was very much rooted in Hillsong’s overall musical identity. Thus the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depended on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. In other words, convergent marketing was inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience that the campaign afforded.

Today, music is experienced as part of a convergent media environment with particular practices and logics. If the medium is indeed the message, than a media ecology perspective that views marketing as sensorial, symbolic and generative – that is, as a sensational form – is essential to understanding congregational music. Whether constituted primarily through oral transmission, the printed word or electronic mediation (or some combination), media environments shape the way congregational music is made and experienced. As the number and type of communication platforms expands, the relationship between them changes; music becomes part of an ever-more dynamic media environment. This has important implications for the understanding of the way people engage with and participate. Thus, congregational music’s dual status as a mediated object and as medium is vital to understanding its role not only in people’s spiritual lives, but also in the ways they experience being human.

References

Arvidsson, Adam. 2006. Brands: Meaning and Value in Media Culture. New York: Routledge.

Blacking, John. 1995. Music Culture & Experience, ed. Reginald Byron. Chicago, IL and London: University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, Heidi. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online: We Are One in the Network. New York: Peter Lang.

———. 2012. ‘How Religious Communities Negotiate New Media Religiosity’. In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Futures, eds Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles Ess, 81–96. New York: Peter Lang.

———. ed. 2013. Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. New York: Routledge.

Carah, Nicholas. 2010. Pop Brands: Branding, Popular Music, and Young People. New York: Peter Lang.

Coleman, Simon. 2000. The Globalisation of Charismatic Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooke, Phil. 2008. Branding Faith: Why Some Churches and NonProfits Impact Culture and Others Don’t. Ventura, CA: Regal.

Dauvergne, Peter, and Genevieve LeBaron. 2014. Protest, Inc. Cambridge: Polity Press.

de Sola Pool, Ithiel. 1983. Technologies of Freedom. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Einstein, Mara. 2008. Brands of Faith: Marketing Religion in a Commercial Age. London: Routledge.

———. 2011. ‘The Evolution of Religious Branding’. Social Compass 58 (3): 331–8.

Forsberg, Geraldine E. 2009. ‘Media Ecology and Theology’. Journal of Communication & Religion 32 (1): 135–56.

Foucault, Michel. 1988. ‘Technologies of the Self’. In Technologies of the Self, eds Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman and Patrick H. Hutton, 16–49. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. http://foucault.info/documents/foucault.technologiesofself.en.html.

Frith, Simon. 1996. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Reprint. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Geddes, Patrick. 1915. Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics. London: Williams & Norgate.

Graham, Mark, and Shahram Khosravi. 2002. ‘Reordering Public and Private in Iranian Cyberspace: Identity, Politics, and Mobilization’. Identities 9 (2): 219–46.

Grimmer, Jim and Ashlyn Grimmer. 2011. ‘Cross Equals Love’. God Knows! Our Journey in Faith, 20 April. http://jimandashlyn.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/cross-equals-love.html.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1992. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hendershot, Heather. 2004. Shaking the World for Jesus: Media and Conservative Evangelical Culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Henrion, F.H.K., and A. Parkin. 1967. Design Coordination and Public Image. London: Studio Vista.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor Adorno. 1976. Dialectic of Enlightenment. New York: Continuum.

Horsfield, Peter G., and Paul Teusner. 2007. ‘A Mediated Religion: Historical Perspectives on Christianity and the Internet’. Studies in World Christianity 13 (3): 278–95.

Houston, Brian. 2014. ‘When Kingdoms Collide’. Hillsong Collected, 17 April. http://hillsong.com/blogs/collected/2014/april/when-kingdoms-collide#.VLAQcid3bFo.

Ingalls, Monique M., Carolyn Landau and Tom Wagner, eds. 2013. Christian Congregational Music. Farnham: Ashgate.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York University Press.

———, Sam Ford and Joshua Green. 2013. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. New York and London: New York University Press.

King, E. Frances. 2010. Material Religion and Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

Langer, Susanne K. 1942. Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lash, Scott, and Celia Lury. 2007. Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Latour, Bruno. 1996. ‘On Interobjectivity’. Mind, Culture, and Activity 3 (4): 228–45.

Lum, Casey Man Kong. 2006. ‘Notes Toward an Intellectual History of Media Ecology’. In Perspectives on Culture, Technology and Communication: The Media Ecology Tradition, ed. Casey Man Kong Lum, 1–60. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Lury, Celia. 2004. Brands: The Logos of the Global Economy. New York: Routledge.

McDannell, Colleen. 1995. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 2001. Understanding Media. London: Routledge.

Maddox, Marion. 2012. ‘“In the Goofy Parking Lot”: Growth Churches as a Novel Religious Form for Late Capitalism’. Social Compass 59 (2): 146–58.

Meyer, Birgit. 2008. ‘Media and the Senses in the Making of Religious Experience: An Introduction’. Material Religion 4 (2): 124–34.

———. 2011. ‘Mediation and Immediacy: Sensational Forms, Semiotic Ideologies and the Question of the Medium’. Social Anthropology 19 (1): 23–39.

Moor, Liz. 2007. The Rise of Brands. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Mumford, Lewis. 1938. The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace.

———. 1961. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. New York: Harcourt Brace & World.

Musa, Bala A., and Ibrahim M. Ahmadu. 2012. ‘New Media, Wikifaith and Church Brandversation: A Media Ecology Perspective’. In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Futures, eds Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles Ess, 63–80. New York: Peter Lang.

Olins, Wally. 1978. The Corporate Personality: An Inquiry into the Nature of Corporate Identity. London: Design Council.

Ong, Walter J. 2012. Orality and Literacy: 30th Anniversary Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Pilditch, James. 1970. Communication by Design: A Study in Corporate Identity. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pine, Joseph B., and James H. Gilmore. 2011. The Experience Economy, Updated Edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Rettberg, Jill Walker. 2008. ‘Blogs, Literacies and the Collapse of Private and Public’. Leonardo Electronic Almanac 16 (2–3). http://jilltxt.net/txt/Blogs--Literacy%20-and-the-Collapse-of-Private-and-Public.pdf.

Riches, Tanya. 2010. ‘SHOUT TO THE LORD! Music and Change at Hillsong: 1996–2007’. Masters diss., University of Sydney, Sydney College of Divinity.

Riches, Tanya, and Tom Wagner. 2012. ‘The Evolution of Hillsong Music: From Australian Pentecostal Congregation into Global Brand’. The Australian Journal of Communication 39 (1): 17–36.

Ritzer, George, and Nathan Jurgenson. 2010. ‘Production, Consumption, Prosumption: The Nature of Capitalism in the Age of the Digital “Prosumer”’. Journal of Consumer Culture 10 (1): 13–36.

Sennett, Richard. 2003. The Fall of Public Man. London and New York: Penguin, 2003.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Stuart, Helen, and Colin Jones. 2004. ‘Corporate Branding in Marketspace’. Corporate Reputation Review 7 (1): 84–93.

Taylor, Timothy. 2012. The Sounds of Capitalism: Advertising, Music, and the Conquest of Culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Toffler, Alvin. 1980. The Third Wave. New York: William Morrow.

Twitchell, James B. 2004. Branded Nation: The Marketing of Megachurch, College Inc., and Museumworld. New York: Simon & Schuster.

———. 2007. Shopping for God: How Christianity Went from In Your Heart to In Your Face. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Wagner, Tom. 2014a. ‘Hearing the ‘Hillsong Sound’: Music, Marketing, Meaning, and Branded Spiritual Experience at a Transnational Megachurch’. PhD diss., Royal Holloway University of London.

———. 2014b. ‘Music, Branding and the Hegemonic Prosumption of Values of an Evangelical Growth Church’. In Religion in Times of Crisis, eds Gladys Ganiel, Heidemarie Winkel and Christophe Monnot, 11–32. Religion and the Social Order 24. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Wind, Jerry, and Vijay Mahajan. 2001. Convergence Marketing: Strategies for Reaching the New Hybrid Consumer. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Wind, Yoram, and Vijay Mahajan. 2002. ‘Convergence Marketing’. Journal of Interactive Marketing 16 (2): 64–79.

Whorf, Benjamin L. 1956. Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Xie, Chunyan, Richard P. Bagozzi and Sigurd V. Troye. 2008. ‘Trying to Prosume: Toward a Theory of Consumers as Co-Creators of Value’. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 36 (1): 109–22.

1 I am adapting this terminology from cultural theorist Celia Lury, who describes the brand as ‘a new media object’ – something that is both comprised of media and is a medium itself (Lury 2004, 1–16). Concomitant with the rise of informational capitalism has been a change in the ontological nature of ‘things’. In the global cultural industry and informational capitalism, things are no longer static, mechanized bits of material (as described by Horkheimer and Adorno 1976), but are ‘dynamic support for practice’ (Lash and Lury 2007, 6). In other words, whereas practice formerly occurred in a frame where culture was the superstructure with a material base, today the superstructure has collapsed into the base – commodity and practice are now one and the same process. Congregational music can be thought of as – and indeed is – practice (Ingalls, Landau and Wagner 2013; Small 1998). However, thinking of it as an object (and the object as process) gives it explanatory power within convergence culture as both a commodity and an affordance (for example, Latour 1996). (Thanks to Monique Ingalls for this point).

2 The show ran from 14 May 2002 to 31 May 2014.

3 It would be more accurate to say that the market does.

4 Although transnational megachurches are likely to be among the most intensively ‘networked’ churches, if only because they possess a great deal of financial and human capital, they are certainly not the only ones that embrace the practices and logics of convergence culture. In order to differentiate themselves in a crowded religious marketplace, evangelical churches are turning to marketing consultancies in greater numbers (Cooke 2008; Einstein 2011; Twitchell 2004, 2007). Size will, to some degree, shape a church’s approach to marketing; however, that approach will also be influenced by broader socio-cultural ideologies (Campbell 2012; Maddox 2012).

5 http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/technology.

6 http://hillsong.com/.

7 For a critical discussion, see Arvidsson 2006.

8 Kutcher’s popular MTV programme Punk’d is a hidden camera practical joke series, in the vein of Candid Camera, where the object of the jokes is a celebrity figure (http://www.mtv.com/shows/punkd/). Examples of Hillsong’s version can be found on YouTube (for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubD7nOlIFVQ.) and are collected at http://myhillsong-easter.tumblr.com/.

9 http://myhillsong.com/easter.

10 http://myhillsong-easter.tumblr.com/.

11 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VC88bvqaUn8.

12 These and many more can be found on photo-sharing websites such as Tumblr (https://www.tumblr.com/tagged/cross-equals-love) and Pinterest (https://www.pinterest.com/timdenhartog/cross-equals-love/).

13 At Hillsong,  symbolizes Jesus’ death on the Cross as His undying love for humanity and The Scarlet Thread symbolizes His death as the cord which binds humanity together. Hillsong’s 2011 Vision Sunday video is available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnG1si3xLto.

symbolizes Jesus’ death on the Cross as His undying love for humanity and The Scarlet Thread symbolizes His death as the cord which binds humanity together. Hillsong’s 2011 Vision Sunday video is available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnG1si3xLto.

14 Hillsong’s brand is anchored by the annual release of two main music series: Hillsong Worship (formerly Hillsong LIVE) and Hillsong United (Riches 2010; Wagner 2014a). It has recently added a third stream, Young and Free, which is music from its youth ministry (http://hillsong.com/youngandfree).

15 Hillsong’s pastors also develop their own preaching themes tailored to the needs of their local congregations. Additionally, Hillsong churches invite guest preachers, although these are usually drawn from a small pool of regulars (for example, T.D. Jakes, Joseph Prince, Judah Smith). What I am trying to show in the above is that the evolution of Hillsong’s organization, image and message are concomitant. Vision Sunday provides an overall ‘framework’ for the year, but is also situated in the message that has evolved since the church began in 1983. See also Riches and Wagner 2012.

(cross equals love) Easter media campaign. Consistent with the practices and logics of convergence culture, the campaign utilizes cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. Part 3 situates the

(cross equals love) Easter media campaign. Consistent with the practices and logics of convergence culture, the campaign utilizes cross-platform communication to spread the church’s Easter message. Part 3 situates the  campaign’s use of music in a larger socio-cultural matrix where music is part of a marketing gestalt. I suggest that the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depends on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. Following Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’ (for example, Meyer 2008, 2011), I propose that a media ecology view of congregational music sees marketing as inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience in convergence culture.

campaign’s use of music in a larger socio-cultural matrix where music is part of a marketing gestalt. I suggest that the spiritual efficacy of the campaign depends on material concerns such as the production, distribution and marketing of the musical product. Following Birgit Meyer’s notion of ‘sensational forms’ (for example, Meyer 2008, 2011), I propose that a media ecology view of congregational music sees marketing as inseparable from – and essential to – the immediacy of the religious experience in convergence culture.