Cornerstone Festival was an annual US Christian music and arts festival held every July in rural western Illinois, about a four hours’ drive southwest of Chicago. Most attendees camped at ‘Cornerstone Farm’, a 500-acre property owned by the organizers, Chicago-based Christian commune Jesus People, USA (or JPUSA). Cornerstone Festival privileged youth-oriented music genres and styles over mainstream, adult-oriented Christian recording artists; its sonic identity had more in common with contemporaneous emo, hardcore, indie rock, metal and punk rock than with contemporary Christian music (CCM), gospel, praise and worship, or other religious musics. Cornerstone’s identity as a Christian festival also set it apart from secular festivals that program similar-sounding artists, and its self-conscious ambivalence towards mainstream Christian music likewise distinguished it from other Christian festivals. In this in-betweenness, Cornerstone articulated a subcultural aesthetic resistant to dominant evangelical culture – itself framed as a subculture by Randall Balmer (1989). This strategy was present in the festival’s official programming, organizers’ goals, ad hoc performances at attendee-operated ‘generator stages’ and attendees’ Cornerstone experiences.

Attendance at Cornerstone peaked in the late 1990s and early 2000s, in part driven by the mainstream success of subcultural Christian artists such as MxPx, P.O.D., Sixpence None the Richer, Switchfoot and others. Facing an increasingly crowded festival market competing for decreasing consumer discretionary income following the 2007–08 financial crisis, however, the festival’s attendance declined sharply in its later years and Cornerstone closed in 2012. Based on interviews with festival staff and industry insiders, historical research and ethnographic fieldwork from 2009 to 2012, this chapter examines the ways in which participants conceptualized, constructed, idealized and mourned Cornerstone’s imagined community. This study reveals the ways in which resistant meanings and ideologies in culture and society are created and circulated through examining the musical identities articulated, performed and experienced by Cornerstone’s staff, artists and attendees.

JPUSA is the most visible descendent of the late 1960s’ Jesus People Movement.1 JPUSA’s 400 members live, work and worship communally, sharing resources and responsibilities. JPUSA’s communal living environment and collective financial, social and theological practices constitute bonds that promote group cohesion and allow individuality within strictly defined boundaries (Young 2012a, 500). Although JPUSA’s communal environment, progressive theology and liberal politics frequently diverge from those of many evangelical congregations – the commune is a part of what Shawn David Young terms the ‘emerging Evangelical Left’ (2012a, 499) – they can also reflect common ground: JPUSA shares with mainstream evangelicalism the basic articles of Christian faith, an affinity for contemporary praise and worship music and a commitment to evangelism and ministry via social action. Its members thus self-consciously negotiate values simultaneously resistant to and convergent with those of what they perceive to be the dominant evangelical mainstream.

This balancing act was present in Cornerstone Festival as well. According to JPUSA member and historian Jon Trott, the commune intended for Cornerstone to bridge the differences ‘between young, culturally radical believers and older, culturally “straight” believers’ through popular music (1996). John Herrin, Cornerstone’s former director, told me in an interview that JPUSA members felt that existing Christian festivals did not meet the needs of artists who ‘were a little too evangelical in who they were and what they stood for to make it in the general [secular music] market, but a little too wild to really play a part of the fairly conservative Christian music scene at the time’.2 Cornerstone’s organizers went out of their way to book these ‘wild’ Christian artists, most of whom played rock subgenres such as heavy metal, indie, new wave and punk, providing what Young describes as ‘a counterpoint to mainstream evangelical festivals’ (2011, 4). Nevertheless, Cornerstone shared a Christian identity and ethics with these other festivals: festival organizers prohibited drugs and alcohol, encouraged modest dress and promoted collective worship services. By balancing conformity and resistance, Cornerstone’s observers actively negotiated a subcultural position, illustrating a larger tension between challenging the aesthetic boundaries of mainstream Christian music while observing core ethical values that distinguish it as non-secular.

The first Cornerstone Festival was held in 1984 at the Lake County Fairgrounds in Grayslake, a Chicago suburb, where it stayed for seven years (Thompson 2000, 148). City and suburban residents could access the festival relatively easily, and curious fans purchased single-day tickets to sample the festival. In 1990, JPUSA bought a farm in western Illinois to host Cornerstone. The commune’s members continued improving the property every year, installing electricity and improving the utilities, digging wells, adding permanent and semi-permanent buildings, and laying gravel roads. The distance made day trips from Chicago to the festival all but impossible, and organizers no longer needed to cater to single-day attendees. Instead, they included campsite access in ticket prices, encouraged attendees to camp onsite throughout the festival’s duration and spread the festival’s programming – not just music but also seminar and film series, organized sports and kids’ events – throughout the event’s four- or five-day duration.

Because the festival was strongly associated with subcultural Christian youth and music, many record labels and recording artists targeting that market considered Cornerstone to be an important promotional site. For example, Christian punk label Tooth & Nail sponsored a full day of performances at the festival from 2000 to 2008, and Cornerstone’s Label Showcase Stage featured ‘up and coming talent’. During the 1980s and 1990s, artists of all styles benefited from performing at Cornerstone to fans who travelled from around the country to attend the festival. John J. Thompson – long-time editor of True Tunes News and later an executive at EMI Christian Music Group – explained in an interview that performing at Cornerstone was significant for subcultural Christian artists who could not otherwise find enough venues for a regional or nationwide tour (see Thompson 2000, 150): ‘Cornerstone was the mothership, it was exclusive, you couldn’t find those bands anywhere else. Most of those bands didn’t ever tour, there wasn’t enough places for them to play to do a tour. … [Cornerstone] was their tour. They could hit all of the interested people in one week’.3

Sarah Thornton argues that the kind of subcultural cohesion described above relies upon media, and Cornerstone proved crucial in this respect (1996; see Bennett and Kahn-Harris 2004, 10). Yes, it was mediated in the ways that attendees experienced the event – promoted via print and online publications, filtered through jumbotrons and PA systems and remembered in photographs and blog posts – but it was also media in its role as a platform for cultural expression and identity performance. This characteristic would be paramount for Stewart Hoover, who writes of media’s capacity ‘to be both shapers of culture and products of that same culture’ (2006, 10, 23). Matthew Engelke follows Hoover in noting that religious media both communicate and facilitate communication, serving as ‘middle grounds … through which something else is communicated, presented, made known’ (Engelke 2012, 227; Hoover 2006, 13).4 In other words, we should ask not what Christian festivals themselves mean but rather what meanings they index. JPUSA used Cornerstone as a tool to communicate their own theological and cultural values; attendees – ‘all of the interested people’ – found Cornerstone to be a communal space in which relationships flourished with each other, with music and musicians, and with God. Cornerstone itself became an index for its own community: attendees referred to musicians they encountered at the festival as ‘Cornerstone artists’, to their festival-mates – especially those whom they did not see regularly elsewhere – as their ‘Cornerstone family’ and to their week-long festival lives as the ‘Cornerstone experience’. What Cornerstone qua media made known, then, was its community and the identities of its participants, which the following fieldnote excerpt illustrates as a mixture of subcultural aesthetics and Christian ethics.

Wednesday, 1 July 2009, 3:30 p.m.: The Burial are a five-piece progressive metal band from South Bend, Indiana, who perform in the Sanctuary Tent on the first official day of Cornerstone Festival. The volume is so loud that the music excites a physical sensation; coupled with the stage presence of the musicians, the energy close to the stage is palpable. Most of the 100 audience members look like they belong at a heavy metal concert: the black clothing, band t-shirts with dark imagery and gothic lettering, long hair, big beards, tattoos and piercings contrast starkly against the more conventionally-attired attendees in the prayer tent across the street. As The Burial pause near the end of their set, guitarist Todd Hatfield exhorts the audience to get more physically engaged with the music. ‘Don’t worry about looking foolish while headbanging’, he says, ‘because the only one watching who matters is God, and he doesn’t care how you look’. Hatfield reminds people to fight against letting the devil infiltrate this community, to allow God to be a part of their festival experience and to engage in conversation with and learn from each other. Before launching into their last song and exciting one final circle pit, Hatfield claims that this music, this concert, this fellowship, ‘this is our sanctuary, this is our worship’.

The Burial and their audience re-signified this Cornerstone concert as a worshipping community. Given the history of Christian anti-rock discourses and the culture wars (Nekola 2013), validating heavy metal performance as a legitimate and authentic worship medium can be a resistant act. At Cornerstone, this moment was common and quotidian, repeated at numerous stages throughout the week. The Cornerstone community emerged as such through shared musical aesthetics, ethics and explicit claims like this one. Simon Frith argues in ‘Music and Identity’ (1996) that individuals both construct their own identities and articulate communities through music, experiencing the subjective and the social simultaneously. In the example above, Hatfield and his fans’ individual and collective identities are bound together through their articulation in the festival space. Music’s unique role in enabling participants to construct these two identities – the individual and the collective – lies in its ability to enact the imagined community through unquestionably real activities: ‘music gives us a real experience of what the ideal could be’ (Frith 1996, 123). In contemporary daily life, this connection between the subjective and the social is less obvious: the recordings we acquire and consume privately index performances; we perform our musical identities online, in Facebook statuses, Instagram photos and tweets whose ephemerality reflects the impermanence of these fleeting social worlds. Festivals are increasingly valuable as mediated spaces where music becomes physical and the imagined community becomes real. Cornerstone did not merely reflect collective values – it enabled staff, artists and attendees to construct a collective identity through shared cultural activities (Frith 1996, 111). Thompson’s final point above – that Cornerstone essentially was the tour for many artists – illustrates the extent to which musical identities and communities were inherently co-constitutive with the festival.

Media studies scholar Marshall McLuhan (1994 [1964]) would ask of festivals qua media, ‘What human capabilities are extended here?’ Cornerstone connected attendees and artists to each other in ways later appropriated by social media: the festival extended not only the audience’s ability to hear and see, but also its capability to network and construct communities with like-minded peripheral and subcultural Christians. According to Benedict Anderson (1991 [1983]), access to media allows individuals to imagine themselves as part of a larger (and largely invisible) trans-local community. Tong Soon Lee (1999) applies Anderson’s imagined community model to religion when describing how the disbursed yet cohesive Singaporean Islamic community connects through a radio broadcast of the adhān (call to prayer). For Monique Ingalls (2011), annual US Christian conferences constitute religious pilgrimage destinations that unite attendees’ imagined communities into congregations. Cornerstone organizers and attendees similarly framed the festival’s physical, social and cultural spaces as an imagined community ritually made manifest for a brief time every year. For many repeat attendees, the festival crowd was not an impersonal gathering but rather an intimate congregational community containing elements of religious revival. Others found meaning in Cornerstone’s resistant potential as a subculture.

Classic subcultural theory is closely identified with the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, whose scholars extended theoretical ideas present in the sociology of deviance, the cultural Marxism of Gramsci, semiotics and post-Second World War British cultural studies (Bennett and Kahn-Harris 2004, 1–6). Dick Hebdige (1979) argued that members of subcultural groups feel alienated from mainstream culture; this alienation prompts cultural resistance, expressed ideologically and by re-signifying existing cultural elements to suit their own purposes or messages – a stylistic process Hebdige describes as bricolage. By explicitly linking aesthetics and ethics, subcultural style provokes alarmist shock, disgust and moral panic, which eventually subside as the mainstream decodes and ‘explains’ the subculture. Because the mainstream controls the mass media, it also controls the discourse about the subculture; these explanations are thus conducted in terms defined by and favourable to the mainstream, diluting the subculture’s discursive significance. Ultimately incorporated back into the mainstream, subcultural style becomes fashionable and commodified; subcultural ideology becomes either exoticized or trivialized; the subculture itself becomes insignificant and ceases to be.

Several recent studies explicitly examine the religious lives of American evangelical teenagers as resistant, comparing and contrasting them against previous generations and examining their relationships with secular popular culture (Smith and Lundquist Denton 2005; Luhr 2009; Dean 2010). Peter Magolda and Kelsey Ebben Gross (2009) explicitly posit evangelical students’ lifestyles at secular colleges as oppositional and resistant to those of their (non-Christian) peers. Similarly, Amy Wilkins (2008) presents college-age Christians as outsiders resisting mainstream collegiate life. Throughout these studies, Christian youth articulate their lifestyles, values and culture as resistant both to the dangerously secular mainstream culture as well as to those of previous generations of Christians, which they perceive as irrelevant and overly concerned with cultural separatism. In doing so, they participate in a longer narrative of countercultural Christianity in the US – self-consciously or not – reaching back at least as far as the emergence of the Jesus People Movement in the late 1960s (see, for example, Shires 2007; Young 2010; Eskridge 2013) and continuing through Balmer’s (1989) framing of US evangelicalism as a subculture.5 Subcultural resistance, in describing these Christians’ liminality, thus frames the ways in which they make sense both of their faiths and of their relationships to non-denominational evangelicalism, mainline Protestantism and mainstream culture at large.

Critics have argued that classical subcultural theory perpetuates gendered hierarchies, essentializes youth consumption as resistance, presumes that youth are necessarily intentional about their subcultural roles and fails to account for localized variations (Bennett and Kahn-Harris 2004, 6–11). Sarah Thornton’s updating of subculture, described above as asserting the primacy of media, corrects earlier scholars’ tacit omission of media’s role in subcultural formation and identity (1996, 117). Scene theory may be a more useful concept for youth cultures whose resistant potential is unclear due to their porous boundaries or revolving memberships. Will Straw suggests that scenes, as spaces in which musicking articulates individual and group identities, are useful for describing music communities ‘whose precise boundaries are invisible and elastic’ (2001, 248). Scene is flexible enough to address the limitations of subculture, yet offers a productive frame through which participants and observers might theorize a community’s spaces, people and those people’s movements through and activities within those spaces (249).

The challenge in analysing Cornerstone qua media is in teasing out the components that articulate subcultural resistance (following Thornton) and those that articulate musical community and identity (following Frith). Resistance can be seen in the style of festival attendees – who represent a cross-section of subcultural groups, including goths, hippies, metalheads and punks, and whose fashion looks the part – and heard in its music. And yet, these stylistic choices might simply be peripheral, neither actively resistant nor tacitly conformant: for some attendees, choosing The Burial’s progressive metal over other festivals’ mainstream CCM is obvious and banal. I’ve argued above that JPUSA intended to re-signify the festival event to showcase underexposed Christian artists, resisting what they perceived to be the conservative programming of other festivals and the mainstream Christian recording. JPUSA indexed resistance in Cornerstone, but this objective ultimately became subservient to the music itself and the resulting mediation of individual and communal identities. Below, I describe how attendees thought of Cornerstone not just as a music festival but as an ‘experience’ integral to their faith community. Music was central to this experience and mediated it at several levels: attendees scheduled daily activities around anticipated concerts, they made new friends and rekindled old relationships in the audiences, and congregants experienced the presence of God both at heavy metal concerts and while singing praise songs at worship services. Many participated in generator stages, unofficial (yet sanctioned) attendee-operated performance spaces on the festival grounds, taking ownership of the festival’s sonic identity. In the hands of Cornerstone’s attendees, then, the festival crowd became an intimate music community and congregation that was simultaneously ephemeral in its limited temporality and permanent as an annual ritual.

Wednesday, 1 July 2009, 11:00 a.m.: I arrive at the festival just in time for the first day of official Cornerstone programming and park in a pasture just inside the front gate. The nearby gravel road, known as Main Street, is lined with large circus tents and open-air stages, which are in turn surrounded by campsites. There are no cars on this road; instead, festival attendees are everywhere, on bicycles, driving golf carts, but mostly walking; some head to the showers with towels and toiletries, many are leaving a centrally-located food vendor with plates of pancakes. I see people at their campsites sitting in circles, heads bowed for prayer; others prepare breakfast over camp stoves.

After buying a large coffee from the pancake vendor, I decide to walk around the grounds – although I had studied the festival map last night, this is my first time on the grounds and I do not yet know my way around. I wander into a Bible study at the Impromptu Stage where most of the crowd are sitting in their own folding camp chairs. After watching a band at the nearby Anchor Stage play a couple of songs, I wander through the two merchandise tents, which are populated mostly by record labels and t-shirt vendors. I explore the festival’s Midway and locate the Gallery Stage, seminar tents, and food vendors. I also find the Cornerstone market (where campers can buy perishables and toiletries) and the press tent (which doubles as the Grrr Records Stage).6 I sit down at a table in the rear of the Gallery to eat my lunch and write some notes. It is barely noon.

12:30 p.m.: I explore the campsite areas, following a path behind the Impromptu Stage. Most campsites consist of a large tent or a circle of small tents facing a common area with camp chairs and cooking equipment; parked cars bound the space. Elaborate sites may have an open-sided shelter for the common area, improvised clotheslines for drying laundry and cooking utensils, old furniture (I see a few upholstered couches and chairs), recreation and sports equipment (I see many beanbag toss games and one ping-pong table) and tables. Because of the diverse ages of campers I see at many of these sites, I assume that they belong to families, groups of families or church groups. Simple sites have a single-person tent or lean-to against a car with no visible cooking equipment. While some campers have arranged their vehicles to provide a degree of privacy to the campsite, most sites face the road: campers often pause conversations to greet passers-by, children and teenagers come and go with frequency and adults chat with those at neighbouring camps.

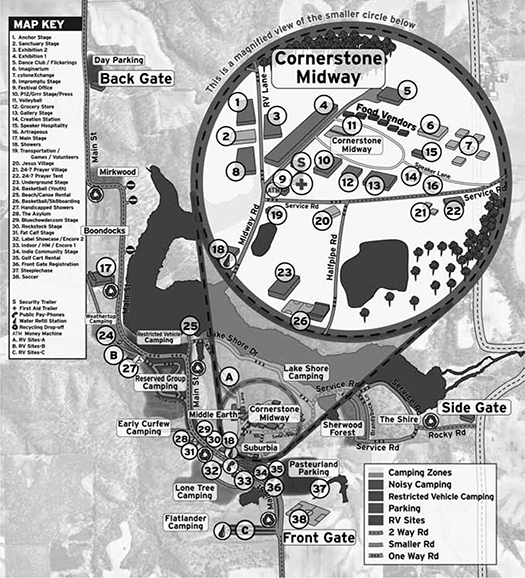

During my first visit to the festival grounds, as described in the preceding fieldnote excerpt, I was struck by the scope of the festival and its attendees. I learned immediately that, like most festivals, Cornerstone was spatially organized such that the official stages and tents acted as centres of activity. As seen in Figure 5.1, Cornerstone’s children’s programs, film series, food court, seminars and volleyball tournament were at the Midway, away from the loudest rock music. Many families and older attendees stayed in one area for much of the time, such as at Gallery Stage, where softer music styles, an on-premises coffee shop, and chairs and tables encouraged lingering throughout the day. In contrast, younger attendees moved often from venue to venue, sometimes in the middle of a set. Some planned out their routes ahead of time, but the sheer number of performances at the six official stages (over 200 concerts during Cornerstone 2009), the prominence of the generator stages and the physical proximity of the venues (many as close as five minutes’ walk) prompted concert-hoppers to be flexible with their itineraries. In contrast to many other music festivals, the movement of attendees at Cornerstone was not highly scripted and instead seemed intended to promote organic and even serendipitous social flows. This strategy reflected both the organizers’ ambivalence towards highly structured, mainstream events and attendees’ expectations of community-building. The Cornerstone audience was united not just by its differences and its faith, but also by its disorganization and its organicism.

Figure 5.1 Cornerstone 2009 Festival map. © Cornerstone Festival / Jesus People USA, reproduced with permission

The campgrounds were also very active. Campers often attended Cornerstone in large groups or arranged to meet each other at the festival. Many told me that they returned every summer, enjoyed reconnecting with acquaintances at the festival and rarely saw their Cornerstone family elsewhere during the year. In an interview, Herrin described Cornerstone as:

… an annual gathering of people that are either Christians or have some connection to the Christian faith who are more interested in discussion, the arts, I think creative music, fellowship. It is an annual renewal. A lot of these folks live all over the country, and … they live lives and interact everyday with people that are not like-minded. This is a chance [for them] to come together … every year, and this has been part of their lives and significant to them in their walk of faith, their friendships, what they’re interested in.7

For many attendees, the festival functioned more like a home church than any other congregation in which they participated. Others claimed that the festival was a place of simultaneous social diversity and cohesion, which they appreciated. For example, a group calling themselves ‘Camp Busted Guitar’ (see Figure 5.2) told me that they only felt fully understood and accepted at Cornerstone, which they had attended for eight years and which had acted as their surrogate family. They appreciated that attendees regularly cross subcultural boundaries that might be less permeable elsewhere: they regularly observed goths, jocks, metalheads, preppies, punks and other stereotypically exclusive groups engaged in fellowship together. ‘It is not the Cornerstone Festival’, one camper told me, ‘it is the Cornerstone Experience.’ They enjoyed listening to punk rock and heavy metal bands, but after their local music scenes died, they did not have easy access to live music outside of Cornerstone. ‘It’s home’, another camper told me, ‘the best week of the year, the best part of the summer’. They made a point to bring first-time attendees with them every year, partly because they found Cornerstone difficult to explain in words, and also partly because they enjoyed experiencing the festival with the first-timers, for whom everything was still new and fresh.

Figure 5.2 Camp Busted Guitar, reproduced with permission of the author

In addition to the hundreds of bands in the official schedule, Cornerstone’s organizers sanctioned attendees to set up their own stages, power PAs with portable generators and independently book bands to perform. Starting in 2009, Cornerstone regulated these stages by requiring (free) permits, assigning locations (mostly along Main Street and Midway Road), prohibiting merchandise sales and restricting their operating hours. Herrin, however, exercised little additional oversight, telling me, ‘We just decided, “Here’s a plot of ground, do your thing”’.8 As seen in Figure 5.3, some generator stages merely offered electricity for amplifiers and a microphone and PA for singers. Others were pseudo-professional venues of similar quality as the festival’s official stages, complete with lighting, professional PAs and monitors, stages and tents. Thirty-one generator stages registered for Cornerstone 2009. Many bands performing at generator stages played multiple sets over the course of the festival. Because they were not part of the official Cornerstone schedule, the bands and stage operators relied on self-promotion to market their concerts to attendees: they posted daily schedules at their stages, announced their schedules around festival grounds with bullhorns and sandwich boards and papered every available surface with flyers.

Figure 5.3 Amateur generator stage and flyers, reproduced with permission of the author

The relationships between the generator stages and official venues at Cornerstone were similar to those between smaller and larger concert venues in local scenes outside of the festival: smaller stages were more willing to book newer or younger artists. As artists gained more fans, they performed at progressively larger stages; many ultimately played the Main Stage. Sometimes touring artists will precede or follow large arena concerts with ‘secret’ performances at smaller venues; in a similar manner, at Cornerstone, bands sometimes played a smaller generator stage concert before or after a higher-profile performance at an official stage. Most generator stages were set up very close to each other along Main Street and Midway Road (see Figure 5.1) and the resulting soundscape could be cacophonous, as this fieldnote excerpt illustrates:

Wednesday, 1 July 2009, 1:30 p.m.: As I walk down Main Street, I pass generator stage after generator stage. The sounds of many generator stage performances overlap; I hear a dozen different bands playing at once. I stop at a few performances; crowd sizes range from a dozen to a hundred or more fans, though most crowds appear to average around fifty listeners. In general, these performers appear to not be well-known artists but young bands trying to engage new fans: many of them offer to hang out after the performance, promote other generator stage concerts later in the week and even give away CDs. Later in the festival, I hear artists performing at official festival venues discuss their history with Cornerstone: many of them started out playing generator stages for a few years and eventually ‘graduated’ to the festival’s official stages after building their audience and attracting the organizers’ attention.

The diversity and breadth of Cornerstone’s generator stages both contributed to the event’s reputation of valuing audience participation and independence, and illustrated larger tensions between the festival’s diverse constituents. While younger festivalgoers might have favoured generator artists over some of the more established artists booked at the official stages (especially during Cornerstone’s later years), long-time attendees constantly complained about the generator scene’s unrelentingly loud hardcore, metal and screamo bands and the resulting noise pollution. In sanctioning generator stages and ceding a degree of control to attendees, festival staff not only further promoted artistic diversity but also encouraged amateur and semi-professional participation in the Christian music industry by maintaining a relatively low entry cost to access Cornerstone’s thousands of attendees (and potential new fans). By actively engaging attendees in the production and mediation of the festival space and soundscape, Herrin and his staff attempted to subvert their own positions of authority and curatorial oversight. This coincided with JPUSA’s overall goal of targeting both fans and performers of subcultural music by enabling attendees to create their own resistant identities, mediated through their own music at their own stages. In empowering attendees in this manner, Cornerstone’s generator stages also contributed to the festival’s potential for mediating musical identities and communities.

Cornerstone’s attendance decreased from a peak of over 25,000 in the late 1990s and early 2000s to around 3,000 paying attendees at the final festival in 2012, despite what is generally regarded as festivals’ overall ascendancy in the music industries during this period (see, for example, Holt 2010). I mentioned above that this decline was largely because of increased competition from other Christian festivals, as well as consumers’ declining discretionary income following the 2007–08 financial crisis. Social media also played a role: its explosive growth allowed fans to learn about, access and support artists and labels without needing Cornerstone as a cultural intermediary. As the festival’s imagined community largely moved online, its physical space was no longer as important a site for the community to gather. Attendees who missed the Cornerstone experience one summer could access online media coverage – both official and unofficial, including blogs, photographs, videos and concert reviews – that masked the declining crowds. Judging by the Facebook responses following Cornerstone’s closing, many former attendees had little idea that attendance had declined so sharply.

Other trends contributed as well: the growing popularity of aggressive rock substyles among Christian music consumers allowed artists to increase their booking fees, frequently pricing them out of Cornerstone’s budget. Cornerstone artists increasingly performed at secular festivals such as Vans Warped Tour and were either unavailable or too costly for Cornerstone.9 Herrin’s booking strategy of prioritizing youth tastes over other demographics was also partly responsible for Cornerstone’s decline. Certainly, other festivals – both Christian and secular – have experienced success booking contemporary artists alongside older, reunited or ‘nostalgia’ acts. The organizers’ nod to ‘old-timer bands’ with 2011’s Jesus People Rally – featuring Daniel Amos, Barry McGuire, Phil Keaggy, Petra, JPUSA’s own Resurrection Band, Randy Stonehill and others – belatedly recognized this potential. In its last several years, the festival’s Main Stage concerts increasingly featured mainstream Christian artists in demand at other major festivals, including David Crowder Band, Family Force 5, P.O.D., Red, Skillet, Switchfoot, tobyMac (formerly of CCM hip-hop group DC Talk) and others. If Cornerstone had been intended to provide a site of resistance and community for subcultural Christians – ‘all the interested people’, as Thompson described them above – then its claim to exclusivity as ‘the mothership’ was increasingly threatened. In other words, the tastes of the mainstream Christian music market gradually shifted closer to those of Cornerstone’s audience over time; the mainstream gradually incorporated the subculture. This shift complicated the festival’s economics; organizers, unprepared for these new financial realities, failed to adjust their booking strategies and budget appropriately and instead participated in an arms race: Cornerstone felt pressured to book bigger and bigger artists who commanded larger and larger fees for fewer and fewer attendees. Although JPUSA had long operated Cornerstone at a deficit, justifying the expense as the cost of ministry, the festival’s growing debt ultimately became an unsustainable liability.

Herrin and his staff made small changes to the festival every year, hoping to enhance attendees’ experiences and cut costs: they adjusted concert times, improved the festival grounds, increased Internet-based festival reporting, moved and conflated stages and partnered with new sponsors. In retrospect, these changes were clear responses to the changing economics of the event and the need to shrink its budget, scope and physical footprint. At Cornerstone 2012, there was no Main Stage; instead, Gallery Stage served as the de facto main concert venue. Most artists agreed to play Cornerstone 2012 for free or reduced fees. The resulting schedule was full of artists whose history with Cornerstone and JPUSA endeared the festival to them. JPUSA announced in advance that Cornerstone 2012 would be the final festival. In a post on the official website, Herrin wrote:

We have the opportunity to come together one last time and bring to a happy, grateful – if tearful – close to this chapter of our lives. … We hope to make this a special gathering to remember, to share stories and encourage one another with the vision of Cornerstone in ways that look back and ahead toward new things God is doing. … Cornerstone 2012 promises to be a time of thankful reflection and sharing among people who’ve walked this significant part of their life’s journey together.10

Cornerstone 2012 was permeated with attitudes of loss, resignation, thankfulness and hope, as the following fieldnote illustrates:

Saturday, 7 July 2012 10:00 a.m.: Many here are genuinely sad that Cornerstone will not be returning next year. This has served as a meeting place of encouragement, understanding, and surrogate family for so many, for so long. It’s much more than a festival. At this morning’s worship service, framed as a benediction for Cornerstone, John J. Thompson moderates thirty minutes of reflections and memories, all of which are sincerely touching. He reflects that if Cornerstone can still be meaningful for attendees without fancy Main Stage production and major artists, then it’s clearly not only about the music. Thompson later says that Cornerstone is his hometown, ‘These are my people, this is my tribe, my dysfunctional family’ [see Thompson 2012].

Performers, attendees, festival staff and volunteers mourned Cornerstone even as it was happening. In speaking with festival organizers and attendees during its final two years, I learned that those who did keep returning were long-time attendees. They had built and maintained an emotional attachment to their festival experiences and community over several years and decades; many experienced a greater degree of community as the festival waned because they shared the event with a larger proportion of fellow long-time attendees, relative to the total festival audience. Musicians spoke frequently of Cornerstone’s importance to their careers and identities as Christian artists. If the sound of subcultural Christian music had been incorporated into the mainstream, many artists and festivalgoers felt that its lyrical themes, theological perspectives and lifestyles were still not well-represented in the broader evangelical culture.

In the weeks and months following the end of Cornerstone on 7 July, attendees continued to mourn the festival. JPUSA sold out of official t-shirts and started taking back orders at the event, which they also sold online until 27 July. The official Cornerstone 2012 recap video was posted on the festival’s website and YouTube, and was shared on Facebook.11 Soundtracked by ‘Farther Along’ by Josh Garrels, a singer/songwriter popular at Cornerstone, the video included clips of audience life at the festival and concluded with Cornerstone’s ‘Viking funeral’: a model longboat was marched down to the farm’s lake, set adrift, lit on fire by arrow and allowed to burn. Even after its death, Cornerstone mediated community and identity: several new Facebook groups enabled former attendees to (re)connect and share their memories. The Cornerstone Memories group has remained active since then, with members posting of the various ways in which Cornerstone has affected their lives. The 30th Cornerstone Festival group’s goal was to channel any frustration from the festival’s closing into productive energy to enact the Cornerstone experience around the country in members’ locales (2013 would have been Cornerstone’s thirtieth anniversary).

The Occupy Cornerstone group was established by activists whose goal was to hold a festival at Cornerstone Farm in 2013 without JPUSA’s involvement. Although the group’s original idea was for something of a squatter festival – rumours circulated at Cornerstone 2012 that the Occupy group was just going to show up in July 2013 regardless – its leaders quickly realized that JPUSA’s endorsement and cooperation would be crucial, both for legal reasons and for communal good will. They attempted to use their platform to raise money to pay off Cornerstone’s debt and then organize their own festival on the land, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. On 23 April 2013, the official Cornerstone Festival Facebook account posted that JPUSA had sold the farm to a private buyer. Occupy Cornerstone’s organizers used the money they had raised to help fund the first AudioFeed Festival in 2013. Located at the Champaign County Fairgrounds in Urbana, Illinois, over 130 miles (209 kilometres) from Cornerstone Farm, AudioFeed was promoted as Cornerstone’s legacy and featured 75 performances – including several JPUSA-affiliated artists and many more who had performed at Cornerstone – to over 2,500 attendees. Cornerstone’s direct descendent is JPUSA’s Wilson Abbey, which opened in early 2013. Wilson Abbey is a multi-use commercial space across the street from JPUSA’s main Chicago residence that was rehabbed into a cultural centre and includes a coffee shop, art gallery, black box theatre and large performance venue alongside offices and space for the commune’s businesses and school.

Existing research into Cornerstone Festival tacitly ignores its potential as a medium and mediated space. Young’s work (2010; 2011; 2012a; 2012b; 2013), while comprehensive, contextualizes Cornerstone within JPUSA’s specific theological and political orientations. My own research (2012) considers Cornerstone within a broader narrative of underground Christian musical activity. Other historians frame Cornerstone as a legacy of the Jesus People Movement without granting it further significance (see, for example, Di Sabatino 1999; Eskridge 2013). Christian music insiders recognize Cornerstone’s importance in fostering peripheral Christian music (Joseph 1999; Thompson 2000) or only mention it tangentially vis-à-vis Christian rock (Howard 1992; Dueck 2000). Outside (non-Christian) observers focus on the characteristics that marked Cornerstone as clearly distinct from (and peripheral to) secular events but tend to dismiss the event as a mere curiosity (see, for example, Whinna and Hunter 2005; Beaujon 2006; Radosh 2008). Future research should consider Cornerstone specifically as a significant and primary locus of contemporary subcultural Christianity and religious festivals generally as mediated spaces; especially as Christian congregational music’s prominence as a research area increases in a variety of academic disciplines.

In this chapter, I’ve argued that Cornerstone Festival provided a safe space far from the constraints of mainstream evangelicalism. Throughout its history, the organizers gradually shifted their ideology from reactive to proactive, but the festival maintained an inclusive, participatory and democratic environment that set it apart from other Christian festivals, enabled and promoted attendee’s active engagement in constructing their own experience, and reflected JPUSA’s Evangelical Left ideologies. If Cornerstone’s roots were in countercultural Jesus People and subcultural Christians rejecting and resisting standard festival practices – re-signifying the festival as a space for community, creativity and worship instead of commerce – then observers might perceive the festival’s ending as an act of incorporation, and that its resistance was no longer relevant. What has become clear in the years since Cornerstone ended, however, is that its legacy has inspired new communities, festivals and projects that still operate on the peripheries of mainstream evangelicalism. Subcultural Christianity, then, has not been fully incorporated – although several of its commodity forms and styles certainly have – but rather has fragmented into smaller communities and congregations, imagined and not.

Anderson, Benedict R. 1991 [1983]. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised and extended edn. London: Verso.

Balmer, Randall Herbert. 1989. Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: A Journey into the Evangelical Subculture in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beaujon, Andrew. 2006. Body Piercing Saved My Life: Inside the Phenomenon of Christian Rock. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Bennett, Andy, and Keith Kahn-Harris, eds. 2004. After Subculture: Critical Studies in Contemporary Youth Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dean, Kenda Creasy. 2010. Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers Is Telling the American Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Di Sabatino, David. 1999. The Jesus People Movement: An Annotated Bibliography and General Resource. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Dueck, Jonathan. 2000. ‘Crossing the Street: Velour 100 and Christian Rock’. Popular Music and Society 24 (2): 127–48.

Engelke, Matthew. 2012. ‘Material Religion’. In The Cambridge Companion to Religious Studies, ed. Robert A. Orsi, 209–29. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eskridge, Larry. 2013. God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frith, Simon. 1996. ‘Music and Identity’. In Questions of Cultural Identity, eds Stuart Hall and Paul Du Gay, 108–27. London: Sage.

Hebdige, Dick. 1979. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Methuen.

Holt, Fabian. 2010. ‘The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age’. European Journal of Cultural Studies 13 (2): 243–61.

Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. London: Routledge.

Howard, Jay R. 1992. ‘Contemporary Christian Music: Where Rock Meets Religion’. Journal of Popular Culture 26 (1): 123–30.

Ingalls, Monique. 2011. ‘Singing Heaven Down to Earth: Spiritual Journeys, Eschatological Sounds, and Community Formation in Evangelical Conference Worship’. Ethnomusicology 55 (2): 255–79.

Joseph, Mark. 1999. The Rock & Roll Rebellion: Why People of Faith Abandoned Rock Music and Why They’re Coming Back. Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers.

Lee, Tong Soon. 1999. ‘Technology and the Production of Islamic Space: The Call to Prayer in Singapore’. Ethnomusicology 43 (1): 86–100.

Luhr, Eileen. 2009. Witnessing Suburbia: Conservatives and Christian Youth Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1994 [1964]. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. 1st MIT Press ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Magolda, Peter, and Kelsey Ebben Gross. 2009. It’s All about Jesus!: Faith As an Oppositional Collegiate Subculture. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Mall, Andrew. 2012. ‘“The Stars Are Underground”: Undergrounds, Mainstreams, and Christian Popular Music’. PhD diss., University of Chicago.

Nekola, Anna. 2013. ‘“More Than Just a Music”: Conservative Christian Anti-Rock Discourse and the U.S. Culture Wars’. Popular Music 32 (3): 407–26.

Radosh, Daniel. 2008. Rapture Ready!: Adventures in the Parallel Universe of Christian Pop Culture. New York: Scribner.

Shires, Preston. 2007. Hippies of the Religious Right: From the Countercultures of Jerry Garcia to the Subculture of Jerry Falwell. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Smith, Christian, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Straw, Will. 2001. ‘Scenes and Sensibilities’. Public 22–3: 245–57.

Thompson, John J. 2000. Raised by Wolves: The Story of Christian Rock & Roll. Toronto: ECW Press.

———. 2012. ‘Goodnight, Cornerstone’. ChristianityToday.com. 3 July. http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2012/julyweb-only/goodnight-cornerstone.html.

Thornton, Sarah. 1996. Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Time. 1971. ‘The New Rebel Cry: Jesus Is Coming!’ 21 June.

Trott, Jon. 1996. ‘Life’s Lessons: A History of Jesus People USA, Part Six’. Cornerstone 25 (108): 47–8.

Whinna, Heather, and Vickie Hunter. 2005. Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Music? Bloomington, IN: Blank Stare Films.

Wilkins, Amy C. 2008. Wannabes, Goths, and Christians: The Boundaries of Sex, Style, and Status. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Young, Shawn David. 2010. ‘From Hippies to Jesus Freaks: Christian Radicalism in Chicago’s Inner-City’. Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 22 (2): 3.

———. 2011. ‘Jesus People USA, the Christian Woodstock, and Conflicting Worlds: Political, Theological, and Musical Evolution, 1972–2010’. PhD diss., Michigan State University.

———. 2012a. ‘Into the Grey: The Left, Progressivism, and Christian Rock in Uptown Chicago’. Religions 3 (2): 498–522.

———. 2012b. ‘Evangelical Youth Culture: Christian Music and the Political’. Religion Compass 6 (6): 323–38.

———. 2013. ‘Apocalyptic Music: Reflections on Countercultural Christian Influence’. Volume! 9 (2): 51–67.

1 See Eskridge (2013) for a general history of the Jesus People Movement and Young (2010; 2011; 2012a) for accounts of JPUSA’s history.

2 John Herrin, interview with author, 16 March 2010.

3 John J. Thompson, interview with author, 9 September 2010.

4 Engelke’s claim here strongly resembles McLuhan’s famous maxim that ‘the medium is the message.’

5 The Jesus People Movement is a prime example of an evangelical group that emerged through resistance; stylistically re-signified dominant forms of religion, worship and ministry; and whose practices – not to mention their music and other stylistic elements – were ultimately incorporated, to varying degrees, into mainstream evangelicalism, mainline Protestantism and sectors of Vatican II Catholicism.

6 Grrr Records is JPUSA’s in-house record label.

7 John Herrin, interview with author, 16 March 2010.

8 John Herrin, interview with author, 9 April 2010.

9 Christian bands who performed at Cornerstone before appearing on Warped Tour’s main stage include Anberlin, August Burns Red, The Devil Wears Prada, Emery, Haste the Day, Mae, mewithoutYou, MxPx, Norma Jean, Paramore, Relient K, and Underoath, among others.

10 Via http://www.cornerstonefestival.com/information/specialAnnouncement.php.

11 See http://www.cornerstonefestival.com/media/videos.php?v=355.