The digital age has facilitated new ways of interacting with music. Engagement with music will no doubt continue to change, driven by technological advances and commercial imperatives. At this moment in history, though, the online media streaming and social networking service YouTube is a, if not the, dominant environment for musical prosumption (the portmanteau of production and consumption). Prosumption, as Wagner articulates, is the ‘Web 2.0’ utilization of ‘materials and infrastructure for meaning- and self-making activities … provided by an organization, but assembled as “user-generated content”’ (2014b, 12). Tschmack, specifically applying this to the current digital musical world, states that ‘strict separation of active music creation and passiv [sic] music consumption is blurring and gives way to a new way of music reception: music prosumption and music produsing [sic], respectively’ (2012, 248). YouTube is particularly conducive to these practices, given its free access and ease of video creation and publication (Winter 2012). Furthermore, as Holt notes, YouTube is a ‘platform that shapes particular ethics, attitudes, and styles of expression’ (2013, 306). Of particular interest in this chapter is the way new, broadly Christian, online communities form via this platform. More specifically, we investigate the characteristics of communities that form around Christian music texts, as represented by popularly viewed YouTube videos that feature professional recordings of ‘famous’ worship songs with mostly self-produced videos. Furthermore, we examine how they replicate (or differ from) existing physically based religious groups. Christian faith has always been mediated to varying degrees through clergy, ritual, architecture and music. However, online mediation of Christian community is nascent and this chapter seeks to explore this growing phenomenon, particularly as it forms around contemporary congregational songs (CCS).1 We refer to mediation in two distinct ways throughout this chapter. First, media, in this case YouTube, uniquely communicates songs to individuals. Thus, we agree with Hennion’s view that ‘[m]ediations are neither mere carriers of the work, nor substitutes which dissolve its reality; they are the art itself, as is particularly obvious in the case of music’ (2003, 84). Second, when referring to mediated online community, we mean those virtual (and possibly imagined) social engagements as facilitated and shaped by the technological media utilized for their formation, or as Hoover puts it, mediation as ‘a part of the fabric of social consciousness, not just an influence on that consciousness’ (2006, 35).

The number of YouTube users globally is estimated to be between 800 million to 1 billion (‘Recording Industry in Numbers’, 2013). Of the hundreds of hours of content that are uploaded every minute, almost 40 per cent is music-related (Skates 2011). It is therefore not surprising that two of the three most-viewed channels belong to the largest providers of music videos on YouTube: VEVO (featuring content from Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group and EMI) and Warner Music Sound (Skates 2011). Furthermore, nine of the ten most viewed videos on YouTube are music videos (‘IFPI Digital Music Report 2013’, 2013). Anyone with a Google+ account can create a YouTube channel; these may take the form of a personal or corporate channel. A channel allows the owner to create, upload and manage video content, access Google analytics, administrate online text discussions connected to one’s video pages, communicate with subscribers and personalize the channel’s online profile, as well as monetize their content if they wish. Although the expectation is that channel owners only upload video content where they have the appropriate rights to do so (either because they own the work, or have obtained the relevant synchronization and/or master recording licenses), often musical content on YouTube is not appropriately licensed. The two common forms of personal channel music uploads include those where a commercial audio recording is used, but the visual content is fan-created, or a full DVD rip (pre-existing video and audio is uploaded). This extensive engagement with music and music videos is observable in Christians’ prosumption of CCS on the site.

Once published, there are many elements of these YouTube CCS videos that viewers might choose to engage with, such as the song lyrics and/or their theology, the musical styles and content, personally constructed meanings, performativity, the artists (worship leaders/bands) and the producers (churches/events/industry). Furthermore, visual content such as staging, lighting, physical movement, images, text and film editing, can contribute to the communication of cultural values and identity. We propose that, whatever the reason or focus of the engagement, it is clear that online communities form around individual YouTube CCS videos. We further suggest that, as the text through which the considerations above are articulated, the individual song (its lyrics and music as rendered in a popular commercial recording) is the centre of gravity of each virtual community. This makes these online CCS communities quite unique, given that Christian groups/communities/churches have most often historically formed around theological and denominational distinctions. While there is strong evidence that people select which church or service they attend based on ‘inspiring worship’ (Powell 2008),2 there is no evidence that they centre around a singular CCS. We suggest that YouTube thus provides a unique platform for the mediation of online Christian community.

The nature of online religious communities is recently of growing interest to researchers. Works such as Exploring Religious Community Online (Campbell 2005) and Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture (Cheong et al. 2012) provide a number of helpful frameworks and perspectives for exploring online religious networks. Campbell articulates the nature and quality of online Christian communities, albeit with a focus on email-based groups. Hutchings proposes a stimulating view of online Christian groups as not only communities, but examples of ‘networked collectives’ and ‘networked individuals’ (2012, 218–21). While these are useful studies, none of them focus on music-based communities; non-religious online music-based communities have received extensive attention (Baym 2007; Hughes and Lang 2003; Jones 2002; Sun et al. 2006; Waldron 2011, 2012), yet religious online music-based communities have been equally neglected by media studies, religious studies and music studies alike. This chapter begins to redress this by providing an initial platform for future research into this area.

A theoretical framework for Christian music-based communities has emerged from Benedict Anderson’s (1991) influential paradigm of ‘imagined’ communities, particularly in the work of Ingalls (2008) and Hartje-Döll (2013). Ingalls adapts Anderson’s concept of national communities and applies it to evangelical Christians who will never know all of their fellow-members, but ‘are nevertheless united by a shared discursive framework that has been enabled by various mass media technologies’ (2008, 13). Building on Ingalls’ work, Hartje-Döll notes that Anderson’s ‘horizontal comradeship’ as applied to evangelical Christians centres around their ‘shared belief in the Gospel and the assumed evangelical core values’ (2013, 143). Wagner also utilizes this paradigm to explore Hillsong’s use of music to ‘position themselves as a distinct [brand] … within the global evangelical Christian imagined … community’ (2014a, 90).

We propose that a synthesis of these various approaches, perspectives and scholarship can contribute to an understanding of online CCS communities. Campbell identifies six attributes that people desire in community: relationship, care, value, intimate communication, connection and shared faith (2005, 187). She further refines these ideas with the words ‘communication, commonality, cooperation, commitment, and care’ to describe online Christian communities (Campbell 2005). Campbell’s work pertains to reasonably stable, like-minded groups contained by email forums. But what of the traits and characteristics of large, international, unfamiliar online groups who form around a single song text? This chapter explores those (imagined) communities – their beliefs, their values, their characteristics and the songs that act as their gravitational centre – considering the differences and similarities between these communities and offline, ‘traditional’, physically proximate groups of believers.

The CCS chosen for this research have the broadest acceptance across denominations, demographics and countries. Of the more than 300,000 CCS licensed by Christian Copyright Licensing International Ltd. (CCLI), regular monitoring and data reporting produces ‘top songs’ lists every six months, identifying the most utilized CCS in various regions around the world. According to the CCLI data from 2012 and 2013, the following five songs transcend national, denominational and cultural boundaries, and are regularly utilized in small and large churches alike:

• ‘10,000 Reasons’ (Jonas Myrin and Matt Redman, © 2011)

• ‘How Great is Our God’ (Chris Tomlin, Jesse Reeves and Ed Cash, © 2004)

• ‘In Christ Alone’ (Keith Getty and Stuart Townend, © 2001)

• ‘Mighty to Save’ (Reuben Morgan and Ben Fielding, © 2006)

• ‘Our God’ (Matt Redman, Jonas Myrin, Chris Tomlin and Jesse Reeves, © 2010).

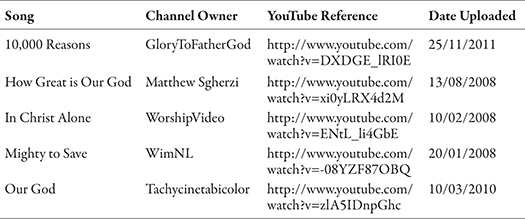

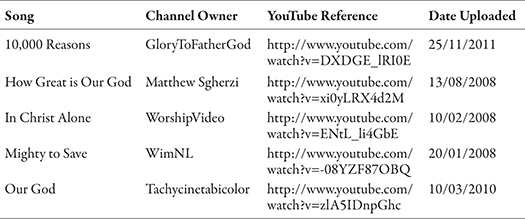

The most popular YouTube mediations of these songs with greatest public engagement – that is to say, the uploaded videos with the highest view counts – served as the primary texts for analysis (see Table 7.1 below). The higher the view count, the greater the possibility for online engagement from viewers, and thus more data about these online communities for analysis in this study.

In line with Garcia and colleagues’ (2009) divisions for social phenomena for the purpose of online ethnographic studies, communities gathered around CCS on YouTube overwhelmingly exist in their ‘solely online’ category. Offline social networks such as friends and family undoubtedly play some role in the propagation of such videos (Afrasiabi Rad and Benyoucef 2011; Broxton et al. 2013). However, there is no indication from the textual content of contributors to suggest that offline relationships play a significant role in shaping the character or qualities of the online community gathered around these songs on YouTube (Garcia et al. 2009, 54–5). Garcia and colleagues affirm that such social phenomena can be reasonably explored within the confines of the online setting. In so doing, they suggest that ‘ethnographers [need to] … develop [particular] skills in the analysis of textual and visual data, and in the interactional organization of text-based CMC [Computer-Mediated Communication]’ (2009, 53). Particular ‘skills’ they raise include ‘lurking’, with the ethical challenges raised by its non-interactive, one-way process. They also warn of the limitations of analysing textual data with its potential lack of context or continuity. While these observations and warnings are reasonable, Garcia and colleagues do not specifically examine YouTube as a textual environment. YouTube textual contributions are asynchronous and ordered not by chronology but by popularity. Thus, context and continuity are less relevant for YouTube music-based communities. This may initially appear as an argument against a strong online CCS community; however, it will be demonstrated that CCS community easily embraces this decontextualized, discontinuous model of communication.

Consequently, this chapter undertakes a qualitative thematic analysis of the textual dialogue provided by contributors in order to gain insight into these communities. Braun and Clarke propose a six-part recursive process for thematic analysis which involves: 1) Familiarizing yourself with your data, 2) Generating initial codes, 3) Searching for themes, 4) Reviewing themes, 5) Defining and naming themes, 6) Producing the report (2006, 87). While their initial stage of transcription was unnecessary, given the existing textual nature of the data, this study applies the methods as outlined for the rest of their qualitative analytical model. YouTube’s dynamic environment is better suited to the analysis of ‘top comments’ (those with the greatest number of ‘likes’ or replies, and thus the greatest community engagement), than the transient plethora of chronologically new posts to these webpages. With this in mind, the top one hundred comments from each video page, an indicative sample, were used for the analysis. These comments were examined over a two-week period (23 July–6 August 2014) as to their correlation with the other data (for example, view counts and ‘likes’/‘dislikes’) in an attempt to capture a fully integrated snapshot of the community.3 While an inductive approach sought to identify prevailing qualities of the community, Braun and Clarke (2006) also offer the theoretical approach, given the qualities of online Christian communities already identified by scholars such as Campbell (2005). Beyond this, limited investigation into the video’s origins and channel owner were undertaken to ascertain their audience, other channel content and their relationship to the myriad other versions of these songs that appear on YouTube. We contacted channel owners in an attempt to gain additional Google Analytic data from them, but unfortunately none responded.

Table 7.1 shows the songs under discussion, their location on YouTube and the date they were uploaded.

Table 7.1 YouTube CCS videos analysed

Large online CCS communities gather around each of these popular worship songs, and we contend that it is the songs themselves that magnetize those communities. However, YouTube contains thousands of versions of each of these songs, and the majority of them do not show significant view counts or other indications of online textual engagement. Why then have these particular mediations garnered such attention and interaction from CCS public? We propose that several features differentiate particular versions of these songs and contribute to users’ online engagement with them, including the quality and sophistication of production, the channel’s subscriber base and the publishing date impact upon the popularity of and engagement with these CCS mediations.

Given the song-centric nature of online CCS communities, it is curious that most of these top videos lack high production quality and technical or aesthetic sophistication (whether audio or video). For example, the ‘10,000 Reasons’ YouTube video is fan-created, containing a static background picture (a silhouette of a man standing with arms outstretched, facing the rising4 sun across a body of water) overlaid with lyrics that appear synchronously with the audio track. Similarly, ‘How Great is Our God’, ‘In Christ Alone’ and ‘Our God’ all have ubiquitous static nature pictures (sometimes with basic visual transitions) overlaid with simple, white text (normally the song’s lyrics).

Audio content is normally sourced from a commercially released album or DVD, so it tends to be of higher quality than the visual content in amateur uploads; however, audio quality alone is no arbiter of online traffic. For example, the audio rip of ‘How Great is Our God’, taken from The Best of Passion (So Far) album (2006), is of quite poor quality, possibly due to audio compression settings when ripped. Two audio glitches, one at 5′31″ and″ another at 5′42″ also suggest a scratched original CD or post-editing issues. Similarly, the audible ‘blip’ at 4′2″ of the ‘In Christ Alone’ video suggests that the channel owner is either not concerned with presenting a ‘professional’ product, or perhaps lacked the technical skills to do so.

With fan-created images and an audio track taken from the Passion 2010 album, Awakening, ‘Our God’ had the most views of all of the videos analysed, with almost 25 million. Yet the level of production likely does not account for its popularity as other more professionally produced music video versions of this song have substantially lower view counts, with the next most-viewed video of ‘Our God’ claiming a comparatively meagre 61,000 views. The number of views for the popular version is also not representative of this owner’s general channel traffic: of the 110 videos posted, most videos have well under 2,000 views (although it is worth noting that most of this channel owner’s videos are not CCS but nature scenes or GoPro or AR Drone camera videos). This suggests that the content of the ‘Our God’ video – specifically the song itself – is the main reason for the video’s popularity.

While ‘Tachycinetabicolor’s ‘Our God’ stands out from the sea of other YouTube versions of the song by virtue of its view count, other CCS under investigation did not have such clear dominance. There are two YouTube versions (WorshipVideo 2008; Renton 2007) of ‘In Christ Alone’ that have similar and significant view counts, but we choose to analyse the version uploaded by ‘WorshipVideo’ that finishes with an extended 30 seconds of silence where a text box appears on the video requesting donations to support the distribution of bibles in China. The audio track, as identified by a contributor to the online comments, is taken from the Adrienne Liesching and Geoff Moore’s version of the song from the album 2003 WOW Worship Yellow. By contrast, the uploaded video created by ‘David Renton’ contains video footage from Mel Gibson’s film Passion Of The Christ in the top half of the screen with the lyrics below combined with a different but untraceable audio source. One way of accounting for the higher view count of the 2008 version is by observing the subscriber base. ‘WorshipVideo’s YouTube channel has 90,000 subscribers, compared with ‘David Renton’s 4,600 subscribers, and is posited more as an educational tool, aiming to equip viewers with skills in musical expressions of worship and thus generating more traffic than ‘David Renton’s channel.

The second most popular mediation of CCS under analysis, and arguably again a result of subscriber numbers, is ‘WimNL’s version of ‘Mighty To Save’, a DVD rip (audio and video) of the track from the Hillsong album Mighty To Save (2005). During our period of investigation, ‘WimNL’s channel focused exclusively on uploads of ripped Hillsong/Hillsong United videos, and had collected over 105,000 subscribers and almost 140 million combined views. ‘WimNL’s version of ‘Mighty To Save’ had been viewed over 23.5 million times since it was uploaded in 2008, 18 months after the release of the DVD. Its success can be viewed in part as a result of the channel’s large subscriber base (three times as many as the primary Hillsong Church YouTube channel5).

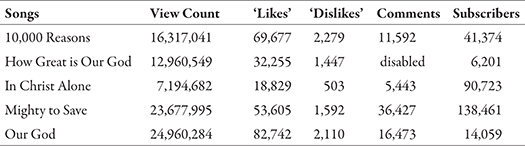

With these contextual considerations of the particular YouTube CCS mediations under analysis, we turn to an examination of the online CCS communities that have formed around them. Table 7.2 documents the relevant YouTube statistics for the songs analysed in this chapter (as of 6 August 2014).

Through the thematic analysis of textual contributions via ‘top comments’, we have identified eight qualities of online CCS communities gathered around YouTube mediations of popular CCS. While these characteristics complement and build on the work of Campbell (2005), they have been identified independently based on our thematic analysis of user comments. The first trait is that they are international. While perhaps obvious, this feature is often not explored in other literature on online Christian communities, yet it clearly impacts the discourse and affects the nature of these communities. Furthermore, it stands in contrast to more homogenous offline local church congregations. A second characteristic of online CCS communities that bears some resemblance to offline Christian communities is that they allow for differing levels of engagement. Other characteristics highlighted below include E-vangelism (Campbell 2005) and testimonies. Leadership is observable, along with pastoral care and prayer, encouragement and instruction, and theological debate. Balancing these traditional elements of Christian groups are the ‘anti-communal’ contributions and roles of ‘flamers’ and ‘trollers’. The following +s will give examples of each of these characteristics and explore how the communities construct and reinforce them.

As noted, first and foremost online CCS communities are international. Clear examples of this dynamic are posts written in languages other than English, such as this Portuguese translation of the final lyrics of the ‘10,000 Reasons’ chorus written by Márcia Stipp:

Ó minha alma

Eu vou adorar seu santo nome

YouTube’s ‘translate’ button allows international readers to understand and engage with comments in other languages and from readers around the globe. Other indicators of internationalization often come from the name and profile pictures users can use to identify themselves and their identities. Google Analytics, available to the channel owner of each video, can further confirm the international nature of the community. For instance, one of the authors of this chapter has CCS on YouTube and people from 31 countries had recently viewed their videos. Given the comments analysed, the CCLI worldwide data, global YouTube data6 and personal data, it is clear that these communities are international but it is also important to note that this data reveals most viewers are from Western nations.

The social media structure of YouTube affords users different possible levels of engagement. Viewing/listening to the song produces an increase in the ‘view count’ and thus includes the viewer at the least level of engagement, an anonymous viewer. It should be noted that, in comparison to offline Christian communities, this level of anonymous engagement is unique to online communities. The viewer can take an additional anonymous step of engagement by clicking on the like/dislike buttons to register their particular binary feeling about the song.7 In order to post comments on YouTube, one must have an account and be logged in. This does not automatically mean that posters are identified. Many profiles use aliases and profile photos that reveal nothing about the person behind the profile. Therefore, even the ability to post comments has levels of engagement that are controllable by the viewer, they can post behind the veil of their avatar, or be completely transparent with who they are and where they are from. In some ways, this is no different to offline communities, where people can share as much or as little information with others as they choose, and the community can cope with people having different levels of engagement in the group. However, total anonymity, as is possible in online CCS communities, is much harder to achieve in offline Christian communities.

In addition, viewers who post comments can choose to reply to other posts, to engage with some other aspect of the community or to post without any reference to other posts or viewers. Two examples are the below posts referencing the ‘likes’/‘dislikes’ tally, the first by ‘Richard Hoenigman’ and the second by ‘Caitlynn Marie’:

why would people put a thumbs down Jesus is are savior and god made us in his image so praise the lord … .

It’s amazing that this song has over thirteen million views. I feel like a lot of times we perceive the world to be a cruel and uncaring place, but seeing that thirteen million views made me rethink my point of view. There are still very many God loving people here on Earth. God bless all who love him as much as I do.

E-vangelism and testimonies abound in the comments from users and ‘Jayoshi’, while engaging with the ‘likes’/‘dislikes’ tally for ‘In Christ Alone’, adds an evangelistic angle: ‘17118 people know the truth, and have acknowledged it. 464 people have yet to hear it’. A clear distinction here is made between those inside the imagined Christian community and those outside; ‘Jayoshi’ effectively defines ‘us’ as those who resonate with the Christian theology of the lyrics, and ‘them’ as those who not only do not resonate with the lyrics but, from his perspective, are actually ‘deaf’ to the ‘truth’. Here we see a missional aspect to the online communities that is akin to evangelical proselytizing. This is taken to a common liturgical feature in the next example, a prayer for those in and at the edge of the faith community posted by ‘Tate Skywalker’ to ‘Our God’: ‘Over 20 million views! Praise the Lord! :D Father I pray that You would reveal Yourself in these people if they don’t already know You and if they do then bless them, oh Lord. In Jesus name, amen.’

Testimonial and evangelical posts often attract ‘likes’ and replies giving them greater prominence among the community. As such, they become strong arbiters of group purpose and design, as in this comment by ‘Arhk Xi’: ‘I personally no longer have my doubts, the LORD is who he is, I’ve spoken with him, I’ve seen him, I’ve touched him. And with that I’d like to say anyone can do the same through the grace granted by Jesus, and with a faith strong enough to embrace that grace.’ Such proselytizing is consistent with how Christians have approached the Internet since its inception (Campbell 2005, 61).

Leadership as authority and as influence are both evident in these communities. Channel owners will sometimes engage the community of posters in an authoritative manner. ‘Ian Boomsma’ writes in ‘10,000 Reasons’, drawing the most ‘likes’ of any comment: ‘hey, this community is getting bigger, i see. as the owner, I need to say something. if you are just gonna keep posting posts with swearing, im not allowing you to be in the group. so if that’s what u r going to do, leave the community, or I will ban you.’

Notice the explicit identification of viewers and posters as being part of a community, and the possibility of inclusion or exclusion from that community. It should be noted that ‘Ian Boomsma’ is not registered as the owner of the channel, but there is the possibility that he used a different email to establish the channel or that he is posing as the channel owner to influence the behaviour of others.

The most liked post (291 ‘likes’) for ‘Our God’ is that of the channel owner, ‘Tachycinetabicolor’, who writes:

Thank you all so much for sharing your testimonies, it is such a blessing to hear how God is working in your lives. Your words are inspiring and encouraging to me and to the people all over the world that are reading them. I am touched by your willingness to open up and share your stories, your prayers for one another, and your willingness to respect and pray for those who are searching or those with views different than your own. God bless!!

Since the channel owner is the default moderator of any discussion on a YouTube video page, he or she may choose to never post anything beyond the initial video, or to be actively engaged, as ‘Tachycinetabicolor’ is. Notice his/her summation of comments made by contributors: testimonies, encouragement, prayers for others in the community, and an awareness of and sensitivity to unbelievers, or believers with diverse doctrinal positions. This is not only a demonstration of leadership, but it can be seen as the taking on of a pastoral role focusing on the spiritual condition and environment of his or her ‘flock’. ‘Tachycinetabicolor’s comment is also a good summary of posts from the communities across all of the most popular CCS on YouTube, with the exception of spammers, trollers and flamers, who he/she conveniently ignores. Of note is that the leadership demonstrated here is not only one of authority – that is to say, the channel owner is addressing the community formed around their video creation – but also of influence in that it is the most liked post. Thus, viewers are giving weight through their ‘likes’ to the poster of this comment, affirming their leadership/pastoral influence in the community. There is a sense here that ‘liking’ a leader’s post enacts a virtual ‘call and response’ element so prevalent in many physical church congregations.

Pastoral care can be seen in the responses to very personal stories contributors, from the safety of their anonymity, feel at liberty to share. One example comes from ‘41cmb41’:

Great song … I’ve always really liked it. My Dad passed away 3 months ago from a battle with cancer. It seems all songs have such a different meaning and perspective now, but especially this one. Dad’s faith was real to the end and it really strengthened ours to see him ‘worship His Holy name’ even/especially ‘on that day when his strength failed … the end drew near and his time came … that part of the song really hits me hard now – I know he is singing His praises even more now singing like never before … it’s hard and yet peaceful … .

A vulnerable post by ‘abel bekele’ (in ‘Mighty To Save’), ‘Feeling empty right now. I need Jesus’, attracted 24 ‘likes’ and 9 replies with a number of the community inviting ‘abel’ (and a contributor who followed, identifying themself as a Hindu) to become a Christian.

These kinds of posts tend to attract affirmation through ‘likes’ and replies. In this way, perhaps ‘likes’ are akin to a knowing look, a pat on the back or shaking hands, in the offline environment: virtual representations of physical signs of affirmation and connection.

The most replied-to post (114 replies) in ‘Mighty To Save’, and most liked (138), belongs to ‘Sinisbal’:

20000000 views!!!!! Wow how much we love our Savior! God who removed homosexuality from my life – I love you. The new life is amazing. God’s Word is the most powerful truth and fact in this whole universe! … If any of you doubt Him for your life, don’t. He is real and He adores you. Let Him restore you. Even though we don’t deserve anything based on what we did and how we sometimes are, He loves us and gives us the best!! … My God is mighty to save!

There is probably no surprise that this comment engendered such engagement. ‘Sinisbal’ engages throughout these replies, ultimately pointing to http://ilivestraight.com/ as a website where he shares his full testimony. While most contributors rejoice with ‘Sinisbal’s ‘deliverance from homosexuality’, flamer ‘BeauJames59’ easily incites a heated discussion that ends up descending into name-calling and inflammatory remarks (an idea we will return to momentarily.) Also, receiving a significant number of ‘likes’ (35) (in ‘In Christ Alone’) was this comment by ‘Georgian Wolf’: ‘I bawled my eyes out, i cant stop crying … In Jesus name i find honour, holiness, purity, strength, love, grace, mercy, meaning!’ Such open emotional transparency is clearly applauded. Once again, ‘likes’ can effectively be seen as the online parallel to encouragement within the YouTube community.

Theological debate is common, especially through the posts that express unorthodox theology. One such example was this post by ‘M6Alex7871992’ in ‘10,000 Reasons’: ‘John 14:20: * On that day, you will realize that i am the Father, and you are in me, and I am in you … We all share a oneness inside us if we close our two physical eyes we can see it! … We Are All one in Spirit . We are all one in Consciousness.’

‘James Bryer’ then replies in a 95-line post with many scripture references trying to point ‘M6Alex’ to the necessity of Jesus Christ as mediator between God and man, rather than the Universalist implications of the original post. Several posts later, this matter is left unresolved and left to drift into the archive of posts. It should be noted that ‘M6Alex’ did receive 14 ‘likes’ to his/her original post, indicating that there were many who shared this theological position. Doctrinal perspectives are commonly expressed without much context, dogmatically but personally and with effort to persuade, aware that it may engender strong responses. For instance, a simple post from ‘Elbert LaGrew’ (in ‘Our God’), ‘None like YOU!’ produced 274 ‘likes’ and 52 replies, most of which were monopolized by two contributors Christopher Wyatt and Roger Askew Jr. who pursued the Armenian/Calvinist argument of free will versus the sovereignty of God. Perhaps affirmations through ‘likes’ or responses help to create the sense of community, and the negotiated communal version of faith that they share through the song.

Despite the centrality of the community’s acceptance of broad Christian doctrine, some approach CCS from very different religious contexts. ‘MrTheStefen’ writes: ‘I’m muslim and I really like this song. It’s so true, God loves us and he’s all around us, always. He’s so powerfull, thank you God, for everything … Christians, Muslims and Jews we have the same benevolent God and he is Greater.’

There are no ‘likes’/’dislikes’ on this post, possibly indicating that either other contributors chose to ignore it, thus communicating a message of unacceptance, although this is uncertain since the majority of posts do not attract ‘likes’/’dislikes’. Alternatively, it’s possible there was simply no contributor on at the time that was interested in engaging with this contributor. What is certain is that this is an anomaly among the posts. It does raise a larger question, however, of the lyrics of CCS: are they not Christian enough to cause other faiths to quickly reject them as representations of their own theologies?

Besides the overwhelming majority of posts praising the songs, or praising/thanking God/Jesus for the song, there are occasionally those who want to express their contrasting views to those of the majority. For example, a user named ‘judas brute’ posted a particularly vitriolic assault against God to ‘In Christ Alone’ that used language many viewers likely found highly offensive. Perhaps significantly, the community has left this post without replies, possibly realizing the futility of such, and leaving this contributor to find his or her own resolution within the broader context of the community comments and the song itself.

Online environments uniquely facilitate potentially noxious communication and interactions. Campbell notes that:

While the absence of nonverbal cues in [online text posts] offers members freedom from some forms of stereotyping and new options for communicating, it also enables negative social behaviour online. [Online text posting] offers quick and easy communication. Anonymity online can lower people’s inhibitions, making it less risky to violate social and cultural standards. (Campbell 2005, 119)

‘Flamers’, ‘trollers’ and ‘spammers’ certainly demonstrate a volition to violate ‘social and cultural standards’. An example of this came from ‘Talon Flame’ (in ‘10,000 Reasons’), ‘Fuck it … Life goes on, am crying so badly*’. This provoked 60 replies, with most of them being from ‘Talon Flame’ himself/herself. Well-meaning contributors try to council, admonish or attack the original poster, but there is clearly no intent from ‘Talon Flame’ to honestly engage in a meaningful dialogue.

‘BalmOfGilead07’, a YouTube channel owner specializing in alarmist and conspiratorial eschatological videos and frequent contributor to CCS discussions on YouTube, writes (in ‘10,000 Reasons’): ‘There will also be a false rapture and the way you will know it’s false is there will be NO Shofar sound, Don’t go looking for it when you hear about it or going to see the false christs even if they’re in front of your house. Stay Safe GOD Bless.’

Although clearly inflammatory, this post received 12 ‘likes’, and 13 replies. Notwithstanding that the thread was quickly hijacked by Rachel Bejerano’s post, ‘You do know that is [sic] was neither God nor Jesus that wrote the bible, right? It was some Christian follower’. Most replies wanted to set Rachel on the ‘right’ path. Another flamer, Richard Platt, incites a discussion of eleven replies around seemingly contradictory Bible passages and the nature of God. Despite the intent, which seems to be simply inflammatory, the community often respond genuinely, and in arguing the basic tenets of evangelical doctrine, the community is defined and reinforced.

As we have demonstrated, online communities form around YouTube versions of CCS. The social networking aspect of YouTube allows for various levels of engagement from community members: simple anonymous viewing, anonymous voting (‘likes’/‘dislikes’), unrelated/independent comments, occasional replies and engagement with other contributors, or complete engagement with the virtual community. These various levels of engagement appear not unlike those in more traditional, physical (offline) Christian communities. It would be rare, however, for an offline Christian community to be as internationally constructed as those identified here. These virtual communities have systems of leadership, promote ‘e-vangelism’ and contain testimonies. They exhibit pastoral care, prayer, encouragement and instruction, and even engage in theological debate. In contrast to this heterogeneous, though variously tolerant community, are ‘flamers’ and ‘trollers’ who sometimes achieve the chaos of contentious and extreme reactions, while also providing an opportunity for the community to position itself in relation to or contrast to these negative voices. Finally, there is a silent majority, who ‘attend’ but don’t otherwise engage. It would be hard to argue, however, that deep relationships are evident.

Thus while we concur with Campbell’s six defining attributes of online Christian communities of relationship, care, value, intimate communication, connection and shared faith, and her refined summary including communication, commonality, cooperation and commitment (2005, 187), it is important to register the subtle differences evident in YouTube CCS communities. First, we agree with Hutchings that commitment (and accountability) are rarely features of such communities (2012, 214). Moreover, what is evident from our preliminary study is that connection and commonality are dominant features of these communities, given they are formed around single song texts. Shared faith in and through the song text certainly exists; however, a theological or denominational homogeneity seems less common. Finally, intimate communication exists as people share vulnerable thoughts and stories allowing the community to (pastorally) care for them via their responses. Many of the characteristics outlined by Campbell are constructed and maintained by a dominant ‘leadership’ within the community, often from the channel owner or a prominent contributor. In contrast to the positive characteristics Campbell outlines, the presence of flamers and other dissonant voices does create a contested space within these YouTube communities that must be negotiated by participants.

These imagined Christian communities are unique in that their single unifying factor is the song. Certainly, offline networks of friends, family or colleagues may also share such videos; however, we have proposed here that the YouTube mediation of the song ought to be understood as the gravitational core of an otherwise diverse and only virtually connected Christian community. Indeed, many of the comments attest to that specific connection. People do not tend to comment on the visual aspects of the video, suggesting that they are secondary to the song itself. One example is a post from ‘GenerationForGod’ asking the community (in ‘In Christ Alone’), ‘Such a beautiful song! What’s the instrument they play at the beginning?’ Eight replies later, a number of suggestions had been made, but the consensus was on a tin whistle. This kind of discussion reinforces the centrality of the music.

These CCS, as mediated through YouTube, have transcended their local church expressions, their denominational origins and even their commercial identities, to become facilitators of imagined Christian community. They do not necessarily replace existing ‘real world’ Christian community (Hutchings 2012), but they certainly extend and reinvent it in line with Ingalls’ and Hartje-Döll’s ideas of imagined evangelical community centred around music. This is perhaps one representation of Ward’s (2013) vision for Liquid Church: people of faith gathered around musical expressions of that faith. Though YouTube’s role in these communities may change over time, online Christian communities gathered around CCS are, we suggest, here to stay and given the current paucity of research on them, are worthy of sustained deep investigation.

Afrasiabi Rad, Amir, and Morad Benyoucef. 2011. ‘Measuring Propagation in Online Social Networks: The Case of YouTube’. Journal of Information Systems Applied Research 4 (2): 63.

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

‘Australian National Church Life Survey’. 2006. http://www.ncls.org.au/default.aspx?sitemapid=6816.

Baym, Nancy K. 2007. ‘The New Shape of Online Community: The Example of Swedish Independent Music Fandom’. First Monday 12 (8). http://firstmonday.org/article/view/1978/1853.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. ‘Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology’. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

Broxton, Tom, Yannet Interian, Jon Vaver and Mirjam Wattenhofer. 2013. ‘Catching a Viral Video’. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 40 (2): 241–59.

Campbell, Heidi. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online: We Are One in the Network. New York: Peter Lang.

Cheong, Pauline Hope, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles M. Ess, eds. 2012. Digital Religion, Social Media, and Culture: Perspectives, Practices, and Futures. New York: Peter Lang.

Evans, Mark. 2006. Open Up the Doors: Music in the Modern Church. London: Equinox.

Garcia, Angela Cora, Alecea I. Standlee, Jennifer Bechkoff and Yan Cui. 2009. ‘Ethnographic Approaches to the Internet and Computer-Mediated Communication’. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38 (1): 52–84.

Hartje-Döll, Gesa. 2013. ‘(Hillsong) United Through Music: Praise and Worship Music and the Evangelical “Imagined Community”’. In Christian Congregational Music: Performance, Identity and Experience, eds Monique Ingalls, Carolyn Landau and Thomas Wagner, 139–50. Farnham: Ashgate.

Hennion, Antoine. 2003. ‘Music and Mediation: Toward a New Sociology of Music’. In The Cultural Study of Music: A Critical Introduction, eds Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert and Richard Middleton, 80–91. New York: Routledge.

Holt, Fabian. 2013. ‘Music in New Media’. In The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture, eds Tim Shephard and Anne Leonard, 301–11. New York: Routledge.

Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. New York: Routledge.

Hughes, Jerald, and Karl Reiner Lang. 2003. ‘If I Had a Song: The Culture of Digital Community Networks and Its Impact on the Music Industry’. International Journal on Media Management 5 (3): 180–89.

Hutchings, Tim. 2012. ‘Creating Church Online: Networks and Collective in Contemporary Christianity’. In Digital Religion, Social Media, and Culture: Perspectives, Practices, and Futures, eds Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles M. Ess, 207–24. New York: Peter Lang.

‘IFPI Digital Music Report 2013’. 2013. IFPI. http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/DMR2013.pdf.

Ingalls, Monique. 2008. ‘Awesome In This Place: Sound, Space, and Identity in Contemporary North American Evangelical Worship’. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

Ingalls, Monique, Anna E. Nekola and Andrew Mall. 2013. ‘Christian Popular Music’. In The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology, eds J.R. Watson and E. Hornby. Available online at www.hymnology.co.uk.

Jones, Steve. 2002. ‘Music That Moves: Popular Music, Distribution and Network Technologies’. Cultural Studies 16 (2): 213–32.

Powell, Ruth. 2008. ‘Australian Church Health & Generational Differences’. NCLS. http://www.ncls.org.au/default.aspx?sitemapid=6401.

‘Recording Industry in Numbers’. 2013. ARIA.com. http://www.aria.com.au/documents/RIN2013.pdf.

Renton, David. ‘In Christ Alone’. YouTube video, 5:50. February 16, 2007. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8welVgKX8Qo.

Skates, Sarah. 2011. ‘Music Is YouTube’s Most Popular Content’. Musicrow.com. 18 August. http://www.musicrow.com/2011/08/music-is-youtubes-most-popular-content/.

Sun, Tao, Seounmi Youn, Guohua Wu and Mana Kuntaraporn. 2006. ‘Online Word-of-Mouth (or Mouse): An Exploration of Its Antecedents and Consequences’. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11 (4): 1104–27.

Tschmuck, Peter. 2012. Creativity and Innovation in the Music Industry. Heigelberg: Springer Science & Business Media.

Wagner, Thomas J. 2014a. ‘Hearing The Hillsong Sound: Music, Marketing, Meaning and Branded Spiritual Experience at a Transnational Megachurch’. PhD diss., Royal Holloway University of London. http://pure.rhul.ac.uk/portal/files/19680902/2014wagnertphd.pdf.

———. 2014b ‘Music, Branding and the Hegemonic Prosumption of Values in an Evangelical Growth Church’. In Religion in Times of Crisis, eds Gladys Ganiel, Heidemarie Winkel and Christophe Monnot, 11–32. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishing.

Waldron, Janice. 2011. ‘Locating Narratives in Postmodern Spaces: A Cyber Ethnographic Field Study of Informal Music Learning in Online Community’. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education 10 (2): 31–60.

———. 2012. ‘YouTube, Fanvids, Forums, Vlogs and Blogs: Informal Music Learning in a Convergent on- and Offline Music Community’. International Journal of Music Education 31 (1): 91–105.

Ward, Peter. 2013. Liquid Church. Peabody, MA: Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Winter, Carsten. 2012. ‘How Media Prosumers Contribute to Social Innovation in Today’s New Networked Music Culture and Economy’. International Journal of Music Business Research 1 (2): 46–73.

Worship Video. ‘In Christ Alone’. YouTube video, 4:56. February 10, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENtL_li4GbE.

1 There are semantic and theological issues with the more popular terms used for this genre, namely ‘praise and worship’ and ‘contemporary worship music’. For further discussion, see Evans (2006) and Ingalls, Nekola and Mall (2013). CCS is herein used for both the singular (contemporary congregational song) and plural (contemporary congregational songs) forms of the term.

2 The Australian National Church Life Survey (2006) showed that among all (adult) age groups ‘vital and nurturing worship’ was identified as one of the top two qualities sought by church attendees.

3 YouTube does not post the date when comments are made, but rather posts the time in reference to the present, for example, two weeks ago, seven days ago, and so on. Given our focus on ‘top comments’ rather than chronological comments, as well as the fact that no comment was older than four months, we have omitted the specific dates for all comments.

4 It could also be the setting sun, although the first verse lyric ‘The sun comes up, it’s a new day dawning’ would suggest otherwise.

5 Hillsong has a number of YouTube channels including Hillsong Church, Hillsong Worship, Hillsong Young & Free, hillsongkids and hillsongunitedTV. An official version of ‘Mighty to Save’ is on the Hillsong Church channel, which has, at the time of this writing, only 36,000 subscribers and 1.5 million views. This is the oldest of their channels, and now no longer posts music videos. However, it should be noted that some of their more recent channels have much higher subscriber bases and much more traffic. For example, Hillsong Worship channel has 200,000 subscribers and hillsongunitedTV has 450,000.

6 See https://www.youtube.com/yt/press/statistics.html.

7 Given that most people do not go out of their way to visit songs they hate on YouTube, the number of likes are expectedly much higher than dislikes.