[1] Ladies and Gentlemen, I am here to express your welcome to Professor Jung, and it gives me great pleasure to do so. We have looked forward, Professor Jung, to your coming for several months with happy anticipation. Many of us no doubt have looked forward to these seminars hoping for new light. Most of us, I trust, are looking forward to them hoping for new light upon ourselves. Many have come here because they look upon you as the man who has saved modern psychology from a dangerous isolation in the range of human knowledge and science into which it was drifting. Some of us have come here because we respect and admire that breadth of vision with which you have boldly made the alliance between philosophy and psychology which has been so condemned in certain other quarters. You have restored for us the idea of value, the concept of human freedom in psychological thought; you have given us certain new ideas that to many of us have been very precious, and above all things you have not relinquished the study of the human psyche at the point where all science ends. For this and many other benefits which are known to each of us independently and individually we are grateful to you, and we anticipate with the highest expectations these meetings.

[2] Ladies and Gentlemen: First of all I should like to point out that my mother tongue is not English; thus if my English is not too good I must ask your forgiveness for any error I may commit.

[3] As you know, my purpose is to give you a short outline of certain fundamental conceptions of psychology. If my demonstration is chiefly concerned with my own principles or my own point of view, it is not that I overlook the value of the great contributions of other workers in this field. I do not want to push myself unduly into the foreground, but I can surely expect my audience to be as much aware of Freud’s and Adler’s merits as I am.

[4] Now as to our procedure, I should like to give you first a short idea of my programme. We have two main topics to deal with, namely, on the one side the concepts concerning the structure of the unconscious mind and its contents; on the other, the methods used in the investigation of contents originating in the unconscious psychic processes. The second topic falls into three parts, first, the word-association method; second, the method of dream-analysis; and third, the method of active imagination.

[5] I know, of course, that I am unable to give you a full account of all there is to say about such difficult topics as, for instance, the philosophical, religious, ehical, and social problems peculiar to the collective consciousness of our time, or the processes of the collective unconscious and the comparative mythological and historical researches necessary for their elucidation. These topics, although apparently remote, are yet the most potent factors in making, regulating, and disturbing the personal mental condition, and they also form the root of disagreement in the field of psychological theories. Although I am a medical man and therefore chiefly concerned with psychopathology, I am nevertheless convinced that this particular branch of psychology can only be benefited by a considerably deepened and more extensive knowledge of the normal psyche in general. The doctor especially should never lose sight of the fact that diseases are disturbed normal processes and not entia per se with a psychology exclusively their own. Similia similibus curantur is a remarkable truth of the old medicine, and as a great truth it is also liable to become great nonsense. Medical psychology, therefore, should be careful not to become morbid itself. One-sidedness and restriction of horizon are well-known neurotic peculiarities.

[6] Whatever I may be able to tell you will undoubtedly remain a regrettably unfinished torso. Unfortunately I take little stock of new theories, as my empirical temperament is more eager for new facts than for what one might speculate about them, although this is, I must admit, an enjoyable intellectual pastime. Each new case is almost a new theory to me, and I am not quite convinced that this standpoint is a thoroughly bad one, particularly when one considers the extreme youth of modern psychology, which to my mind has not yet left its cradle. I know, therefore, that the time for general theories is not yet ripe. It even looks to me sometimes as if psychology had not yet understood either the gigantic size of its task, or the perplexingly and distressingly complicated nature of its subject-matter: the psyche itself. It seems as if we were just waking up to this fact, and that the dawn is still too dim for us to realize in full what it means that the psyche, being the object of scientific observation and judgment, is at the same time its subject, the means by which you make such observations. The menace of so formidably vicious a circle has driven me to an extreme of caution and relativism which has often been thoroughly misunderstood.

[7] I do not want to disturb our dealings by bringing up disquieting critical arguments. I only mention them as a sort of anticipatory excuse for seemingly unnecessary complications. I am not troubled by theories, but a great deal by facts; and I beg you therefore to keep in mind that the shortness of time at my disposal does not allow me to produce all the circumstantial evidence which would substantiate my conclusions. I especially refer here to the intricacies of dream-analysis and to the comparative method of investigating the unconscious processes. In short, I have to depend a great deal upon your goodwill, but I realize naturally it is my own task in the first place to make things as plain as possible.

[8] Psychology is a science of consciousness, in the very first place. In the second place, it is the science of the products of what we call the unconscious psyche. We cannot directly explore the unconscious psyche because the unconscious is just unconscious, and we have therefore no relation to it. We can only deal with the conscious products which we suppose have originated in the field called the unconscious, that field of “dim representations” which the philosopher Kant in his Anthropology1 speaks of as being half a world. Whatever we have to say about the unconscious is what the conscious mind says about it. Always the unconscious psyche, which is entirely of an unknown nature, is expressed by consciousness and in terms of consciousness, and that is the only thing we can do. We cannot go beyond that, and we should always keep it in mind as an ultimate critique of our judgment.

[9] Consciousness is a peculiar thing. It is an intermittent phenomenon. One-fifth, or one-third, or perhaps even one-half of our human life is spent in an unconscious condition. Our early childhood is unconscious. Every night we sink into the unconscious, and only in phases between waking and sleeping have we a more or less clear consciousness. To a certain extent it is even questionable how clear that consciousness is. For instance, we assume that a boy or girl ten years of age would be conscious, but one could easily prove that it is a very peculiar kind of consciousness, for it might be a consciousness without any consciousness of the ego. I know a number of cases of children eleven, twelve, and fourteen years of age, or even older, suddenly realizing “I am.” For the first time in their lives they know that they themselves are experiencing, that they are looking back over a past in which they can remember things happening but cannot remember that they were in them.

[10] We must admit that when we say “I” we have no absolute criterion whether we have a full experience of “I” or not. It might be that our realization of the ego is still fragmentary and that in some future time people will know very much more about what the ego means to man than we do. As a matter of fact, we cannot see where that process might ultimately end.

[11] Consciousness is like a surface or a skin upon a vast unconscious area of unknown extent. We do not know how far the unconscious rules because we simply know nothing of it. You cannot say anything about a thing of which you know nothing. When we say “the unconscious” we often mean to convey something by the term, but as a matter of fact we simply convey that we do not know what the unconscious is. We have only indirect proofs that there is a mental sphere which is subliminal. We have some scientific justification for our conclusion that it exists. From the products which that unconscious mind produces we can draw certain conclusions as to its possible nature. But we must be careful not to be too anthropomorphic in our conclusions, because things might in reality be very different from what our consciousness makes them.

[12] If, for instance, you look at our physical world and if you compare what our consciousness makes of this same world, you find all sorts of mental pictures which do not exist as objective facts. For instance, we see colour and hear sound, but in reality they are oscillations. As a matter of fact, we need a laboratory with very complicated apparatus in order to establish a picture of that world apart from our senses and apart from our psyche; and I suppose it is very much the same with our unconscious—we ought to have a laboratory in which we could establish by objective methods how things really are when in an unconscious condition. So any conclusion or any statement I make in the course of my lectures about the unconscious should be taken with that critique in mind. It is always as if, and you should never forget that restriction.

[13] The conscious mind moreover is characterized by a certain narrowness. It can hold only a few simultaneous contents at a given moment. All the rest is unconscious at the time, and we only get a sort of continuation or a general understanding or awareness of a conscious world through the succession of conscious moments. We can never hold an image of totality because our consciousness is too narrow; we can only see flashes of existence. It is always as if we were observing through a slit so that we only see a particular moment; all the rest is dark and we are not aware of it at that moment. The area of the unconscious is enormous and always continuous, while the area of consciousness is a restricted field of momentary vision.

[14] Consciousness is very much the product of perception and orientation in the external world. It is probably localized in the cerebrum, which is of ectodermic origin and was probably a sense organ of the skin at the time of our remote ancestors. The consciousness derived from that localization in the brain therefore probably retains these qualities of sensation and orientation. Peculiarly enough, the French and English psychologists of the early seventeenth and eighteenth centuries tried to derive consciousness from the senses as if it consisted solely of sense data. That is expressed by the famous formula Nihil est in intellectu quod non fuerit in sensu.2 You can observe something similar in modern psychological theories. Freud, for instance, does not derive the conscious from sense data, but he derives the unconscious from the conscious, which is along the same rational line.

[15] I would put it the reverse way: I would say the thing that comes first is obviously the unconscious and that consciousness really arises from an unconscious condition. In early childhood we are unconscious; the most important functions of an instinctive nature are unconscious, and consciousness is rather the product of the unconscious. It is a condition which demands a violent effort. You get tired from being conscious. You get exhausted by consciousness. It is an almost unnatural effort. When you observe primitives, for instance, you will see that on the slightest provocation or with no provocation whatever they doze off, they disappear. They sit for hours on end, and when you ask them, “What are you doing? What are you thinking?” they are offended, because they say, “Only a man that is crazy thinks—he has thoughts in his head. We do not think.” If they think at all, it is rather in the belly or in the heart. Certain Negro tribes assure you that thoughts are in the belly because they only realize those thoughts which actually disturb the liver, intestines, or stomach. In other words, they are conscious only of emotional thoughts. Emotions and affects are always accompanied by obvious physiological innervations.

[16] The Pueblo Indians told me that all Americans are crazy, and of course I was somewhat astonished and asked them why. They said, “Well, they say they think in their heads. No sound man thinks in the head. We think in the heart.” They are just about in the Homeric age, when the diaphragm (phren = mind, soul) was the seat of psychic activity. That means a psychic localization of a different nature. Our concept of consciousness supposes thought to be in our most dignified head. But the Pueblo Indians derive consciousness from the intensity of feeling. Abstract thought does not exist for them. As the Pueblo Indians are sun-worshippers, I tried the argument of St. Augustine on them. I told them that God is not the sun but the one who made the sun.3 They could not accept this because they cannot go beyond the perceptions of their senses and their feelings. Therefore consciousness and thought to them are localized in the heart. To us, on the other hand, psychic activities are nothing. We hold that dreams and fantasies are localized “down below,” therefore there are people who speak of the sub-conscious mind, of the things that are below consciousness.

[17] These peculiar localizations play a great role in so-called primitive psychology, which is by no means primitive. For instance if you study Tantric Yoga and Hindu psychology you will find the most elaborate system of psychic layers, of localizations of consciousness up from the region of the perineum to the top of the head. These “centres” are the so-called chakras4 and you not only find them in the teachings of yoga but can discover the same idea in old German alchemical books,5 which surely do not derive from a knowledge of yoga.

[18] The important fact about consciousness is that nothing can be conscious without an ego to which it refers. If something is not related to the ego then it is not conscious. Therefore you can define consciousness as a relation of psychic facts to the ego. What is that ego? The ego is a complex datum which is constituted first of all by a general awareness of your body, of your existence, and secondly by your memory data; you have a certain idea of having been, a long series of memories. Those two are the main constituents of what we call the ego. Therefore you can call the ego a complex of psychic facts. This complex has a great power of attraction, like a magnet; it attracts contents from the unconscious, from that dark realm of which we know nothing; it also attracts impressions from the outside, and when they enter into association with the ego they are conscious. If they do not, they are not conscious.

[19] My idea of the ego is that it is a sort of complex. Of course, the nearest and dearest complex which we cherish is our ego. It is always in the centre of our attention and of our desires, and it is the absolutely indispensable centre of consciousness. If the ego becomes split up, as in schizophrenia, all sense of values is gone, and also things become inaccessible for voluntary reproduction because the centre has split and certain parts of the psyche refer to one fragment of the ego and certain other contents to another fragment of the ego. Therefore, with a schizophrenic, you often see a rapid change from one personality into another.

[20] You can distinguish a number of functions in consciousness. They enable consciousness to become oriented in the field of ectopsychic facts and endopsychic facts. What I understand by the ectopsyche is a system of relationship between the contents of consciousness and facts and data coming in from the environment. It is a system of orientation which concerns my dealing with the external facts given to me by the function of my senses. The endopsyche, on the other hand, is a system of relationship between the contents of consciousness and postulated processes in the unconscious.

[21] In the first place we will speak of the ectopsychic functions. First of all we have sensation,6 our sense function. By sensation I understand what the French psychologists call “la fonction du réel,” which is the sum-total of my awareness of external facts given to me through the function of my senses. So I think that the French term “la fonction du réel” explains it in the most comprehensive way. Sensation tells me that something is: it does not tell me what it is and it does not tell me other things about that something; it only tells me that something is.

[22] The next function that is distinguishable is thinking.7 Thinking, if you ask a philosopher, is something very difficult, so never ask a philosopher about it because he is the only man who does not know what thinking is. Everybody else knows what thinking is. When you say to a man, “Now think properly,” he knows exactly what you mean, but a philosopher never knows. Thinking in its simplest form tells you what a thing is. It gives a name to the thing. It adds a concept because thinking is perception and judgment. (German psychology calls it apperception.)8

[23] The third function you can distinguish and for which ordinary language has a term is feeling.9 Here minds become very confused and people get angry when I speak about feeling, because according to their view I say something very dreadful about it. Feeling informs you through its feeling-tones of the values of things. Feeling tells you for instance whether a thing is acceptable or agreeable or not. It tells you what a thing is worth to you. On account of that phenomenon, you cannot perceive and you cannot apperceive without having a certain feeling reaction. You always have a certain feeling-tone, which you can even demonstrate by experiment. We will talk of these things later on. Now the “dreadful” thing about feeling is that it is, like thinking, a rational10 function. All men who think are absolutely convinced that feeling is never a rational function but, on the contrary, most irrational. Now I say: Just be patient for a while and realize that man cannot be perfect in every respect. If a man is perfect in his thinking he is surely never perfect in his feeling, because you cannot do the two things at the same time; they hinder each other. Therefore when you want to think in a dispassionate way, really scientifically or philosophically, you must get away from all feeling-values. You cannot be bothered with feeling-values at the same time, otherwise you begin to feel that it is far more important to think about the freedom of the will than, for instance, about the classification of lice. And certainly if you approach from the point of view of feeling the two objects are not only different as to facts but also as to value. Values are no anchors for the intellect, but they exist, and giving value is an important psychological function. If you want to have a complete picture of the world you must necessarily consider values. If you do not, you will get into trouble. To many people feeling appears to be most irrational, because you feel all sorts of things in foolish moods; therefore everybody is convinced, in this country particularly, that you should control your feelings. I quite admit that this is a good habit and wholly admire the English for that faculty. Yet there are such things as feelings, and I have seen people who control their feelings marvellously well and yet are terribly bothered by them.

[24] Now the fourth function. Sensation tells us that a thing is. Thinking tells us what that thing is, feeling tells us what it is worth to us. Now what else could there be? One would assume one has a complete picture of the world when one knows there is something, what it is, and what it is worth. But there is another category, and that is time. Things have a past and they have a future. They come from somewhere, they go to somewhere, and you cannot see where they came from and you cannot know where they go to, but you get what the Americans call a hunch. For instance, if you are a dealer in art or in old furniture you get a hunch that a certain object is by a very good master of 1720, you get a hunch that it is good work. Or you do not know what shares will do after a while, but you get the hunch that they will rise. That is what is called intuition,11 a sort of divination, a sort of miraculous faculty. For instance, you do not know that your patient has something on his mind of a very painful kind, but you “get an idea,” you “have a certain feeling,” as we say, because ordinary language is not yet developed enough for one to have suitably defined terms. The word intuition becomes more and more a part of the English language, and you are very fortunate because in other languages that word does not exist. The Germans cannot even make a linguistic distinction between sensation and feeling. It is different in French; if you speak French you cannot possibly say that you have a certain “sentiment dans l’estomac,” you will say “sensation”; in English you also have your distinctive words for sensation and feeling. But you can mix up feeling and intuition easily. Therefore it is an almost artificial distinction I make here, though for practical reasons it is most important that we make such a differentiation in scientific language. We must define what we mean when we use certain terms, otherwise we talk an unintelligible language, and in psychology this is always a misfortune. In ordinary conversation, when a man says feeling, he means possibly something entirely different from another fellow who also talks about feeling. There are any number of psychologists who use the word feeling, and they define it as a sort of crippled thought. “Feeling is nothing but an unfinished thought”—that is the definition of a well-known psychologist. But feeling is something genuine, it is something real, it is a function, and therefore we have a word for it. The instinctive natural mind always finds the words that designate things which really have existence. Only psychologists invent words for things that do not exist.

[25] The last-defined function, intuition, seems to be very mysterious, and you know I am “very mystical,” as people say. This then is one of my pieces of mysticism! Intuition is a function by which you see round corners, which you really cannot do; yet the fellow will do it for you and you trust him. It is a function which normally you do not use if you live a regular life within four walls and do regular routine work. But if you are on the Stock Exchange or in Central Africa, you will use your hunches like anything. You cannot, for instance, calculate whether when you turn round a corner in the bush you will meet a rhinoceros or a tiger—but you get a hunch, and it will perhaps save your life. So you see that people who live exposed to natural conditions use intuition a great deal, and people who risk something in an unknown field, who are pioneers of some sort, will use intuition. Inventors will use it and judges will use it. Whenever you have to deal with strange conditions where you have no established values or established concepts, you will depend upon that faculty of intuition.

[26] I have tried to describe that function as well as I can, but perhaps it is not very good. I say that intuition is a sort of perception which does not go exactly by the senses, but it goes via the unconscious, and at that I leave it and say “I don’t know how it works.” I do not know what is happening when a man knows something he definitely should not know. I do not know how he has come by it, but he has it all right and he can act on it. For instance, anticipatory dreams, telepathic phenomena, and all that kind of thing are intuitions. I have seen plenty of them, and I am convinced that they do exist. You can see these things also with primitives. You can see them everywhere if you pay attention to these perceptions that somehow work through the subliminal data, such as sense-perceptions so feeble that our consciousness simply cannot take them in. Sometimes, for instance, in cryptomnesia, something creeps up into consciousness; you catch a word which gives you a suggestion, but it is always something that is unconscious until the moment it appears, and so presents itself as if it had fallen from heaven. The Germans call this an Einfall, which means a thing which falls into your head from nowhere. Sometimes it is like a revelation. Actually, intuition is a very natural function, a perfectly normal thing, and it is necessary, too, because it makes up for what you cannot perceive or think or feel because it lacks reality. You see, the past is not real any more and the future is not as real as we think. Therefore we must be very grateful to heaven that we have such a function which gives us a certain light on those things which are round the corners. Doctors, of course, being often presented with the most unheard-of situations, need intuition a great deal. Many a good diagnosis comes from this “very mysterious” function.

[27] Psychological functions are usually controlled by the will, or we hope they are, because we are afraid of everything that moves by itself. When the functions are controlled they can be excluded from use, they can be suppressed, they can be selected, they can be increased in intensity, they can be directed by will-power, by what we call intention. But they also can function in an involuntary way, that is, they think for you, they feel for you—very often they do this and you cannot even stop them. Or they function unconsciously so that you do not know what they have done, though you might be presented, for instance, with the result of a feeling process which has happened in the unconscious. Afterwards somebody will probably say, “Oh, you were very angry, or you were offended, and therefore you reacted in such and such a way.” Perhaps you are quite unconscious that you have felt in that way, nevertheless it is most probable that you have. Psychological functions, like the sense functions, have their specific energy. You cannot dispose of feeling, or of thinking, or of any of the four functions. No one can say, “I will not think”—he will think inevitably. People cannot say, “I will not feel”—they will feel because the specific energy invested in each function expresses itself and cannot be exchanged for another.

[28] Of course, one has preferences. People who have a good mind prefer to think about things and to adapt by thinking. Other people who have a good feeling function are good social mixers, they have a great sense of values; they are real artists in creating feeling situations and living by feeling situations. Or a man with a keen sense of objective observation will use his sensation chiefly, and so on. The dominating function gives each individual his particular kind of psychology. For example, when a man uses chiefly his intellect, he will be of an unmistakable type, and you can deduce from that fact the condition of his feeling. When thinking is the dominant or superior function, feeling is necessarily in an inferior condition.12 The same rule applies to the other three functions. But I will show you that with a diagram which will make it clear.

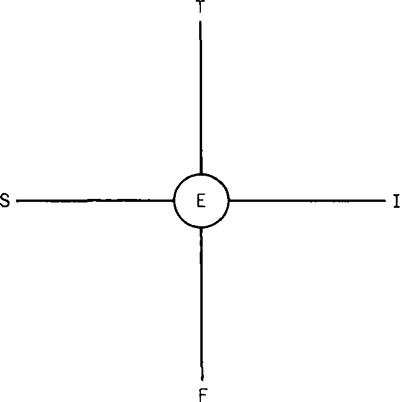

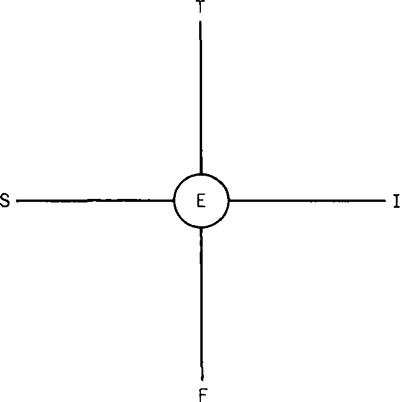

[29] You can make the so-called cross of the functions (Figure 1).

FIG. 1. The Functions

In the centre is the ego (E), which has a certain amount of energy at its disposal, and that energy is the will-power. In the case of the thinking type, that will-power can be directed to thinking (T). Then we must put feeling (F) down below, because it is, in this case, the inferior function.13 That comes from the fact that when you think you must exclude feeling, just as when you feel you must exclude thinking. If you are thinking, leave feeling and feeling-values alone, because feeling is most upsetting to your thoughts. On the other hand people who go by feeling-values leave thinking well alone, and they are right to do so, because these two different functions contradict each other. People have sometimes assured me that their thinking was just as differentiated as their feeling, but I could not believe it, because an individual cannot have the two opposites in the same degree of perfection at the same time.

[30] The same is the case with sensation (S) and intuition (I). How do they affect each other? When you are observing physical facts you cannot see round corners at the same time. When you observe a man who is working by his sense function you will see, if you look at him attentively, that the axes of his eyes have a tendency to converge and to come together at one point. When you study the expression or the eyes of intuitive people, you will see that they only glance at things—they do not look, they radiate at things because they take in their fulness, and among the many things they perceive they get one point on the periphery of their field of vision and that is the hunch. Often you can tell from the eyes whether people are intuitive or not. When you have an intuitive attitude you usually do not as a rule observe the details. You try always to take in the whole of a situation, and then suddenly something crops up out of this wholeness. When you are a sensation type you will observe facts as they are, but then you have no intuition, simply because the two things cannot be done at the same time. It is too difficult, because the principle of the one function excludes the principle of the other function. That is why I put them here as opposites.

[31] Now, from this simple diagram you can arrive at quite a lot of very important conclusions as to the structure of a given consciousness. For instance, if you find that thinking is highly differentiated, then feeling is undifferentiated. What does that mean? Does it mean these people have no feelings? No, on the contrary. They say, “I have very strong feelings. I am full of emotion and temperament.” These people are under the sway of their emotions, they are caught by their emotions, they are overcome by their emotions at times. If, for instance, you study the private life of professors it is a very interesting study. If you want to be fully informed as to how the intellectual behaves at home, ask his wife and she will be able to tell you a story!

[32] The reverse is true of the feeling type. The feeling type, if he is natural, never allows himself to be disturbed by thinking; but when he gets sophisticated and somewhat neurotic he is disturbed by thoughts. Then thinking appears in a compulsory way, he cannot get away from certain thoughts. He is a very nice chap, but he has extraordinary convictions and ideas, and his thinking is of an inferior kind. He is caught by this thinking, entangled in certain thoughts; he cannot disentangle because he cannot reason, his thoughts are not movable. On the other hand, an intellectual, when caught by his feelings, says, “I feel just like that,” and there is no argument against it. Only when he is thoroughly boiled in his emotion will he come out of it again. He cannot be reasoned out of his feeling, and he would be a very incomplete man if he could.

[33] The same happens with the sensation type and the intuitive type. The intuitive is always bothered by the reality of things; he fails from the standpoint of realities; he is always out for the possibilities of life. He is the man who plants a field and before the crop is ripe is off again to a new field. He has ploughed fields behind him and new hopes ahead all the time, and nothing comes off. But the sensation type remains with things. He remains in a given reality. To him a thing is true when it is real. Consider what it means to an intuitive when something is real. It is just the wrong thing; it should not be, something else should be. But when a sensation type does not have a given reality—four walls in which to be—he is sick. Give the intuitive type four walls in which to be, and the only thing is how to get out of it, because to him a given situation is a prison which must be undone in the shortest time so that he can be off to new possibilities.

[34] These differences play a very great role in practical psychology. Do not think I am putting people into this box or that and saying, “He is an intuitive,” or “He is a thinking type.” People often ask me, “Now, is So-and-So not a thinking type?” I say, “I never thought about it,” and I did not. It is no use at all putting people into drawers with different labels. But when you have a large empirical material, you need critical principles of order to help you to classify it. I hope I do not exaggerate, but to me it is very important to be able to create a kind of order in my empirical material, particularly when people are troubled and confused or when you have to explain them to somebody else. For instance, if you have to explain a wife to a husband or a husband to a wife, it is often very helpful to have these objective criteria, otherwise the whole thing remains “He said”—“She said.”

[35] As a rule, the inferior function does not possess the qualities of a conscious differentiated function. The conscious differentiated function can as a rule be handled by intention and by the will. If you are a real thinker, you can direct your thinking by your will, you can control your thoughts. You are not the slave of your thoughts, you can think of something else. You can say, “I can think something quite different, I can think the contrary.” But the feeling type can never do that because he cannot get rid of his thought. The thought possesses him, or rather he is possessed by thought. Thought has a fascination for him, therefore he is afraid of it. The intellectual type is afraid of being caught by feeling because his feeling has an archaic quality, and there he is like an archaic man—he is the helpless victim of his emotions. It is for this reason that primitive man is extraordinarily polite, he is very careful not to disturb the feelings of his fellows because it is dangerous to do so. Many of our customs are explained by that archaic politeness. For instance, it is not the custom to shake hands with somebody and keep your left hand in your pocket, or behind your back, because it must be visible that you do not carry a weapon in that hand. The Oriental greeting of bowing with hands extended palms upward means “I have nothing in my hands.” If you kowtow you dip your head to the feet of the other man so that he sees you are absolutely defenceless and that you trust him completely. You can still study the symbolism of manners with primitives, and you can also see why they are afraid of the other fellow. In a similar way, we are afraid of our inferior functions. If you take a typical intellectual who is terribly afraid of falling in love, you will think his fear very foolish. But he is most probably right, because he will very likely make foolish nonsense when he falls in love. He will be caught most certainly, because his feeling only reacts to an archaic or to a dangerous type of woman. This is why many intellectuals are inclined to marry beneath them. They are caught by the landlady perhaps, or by the cook, because they are unaware of their archaic feeling through which they get caught. But they are right to be afraid, because their undoing will be in their feeling. Nobody can attack them in their intellect. There they are strong and can stand alone, but in their feelings they can be influenced, they can be caught, they can be cheated, and they know it. Therefore never force a man into his feeling when he is an intellectual. He controls it with an iron hand because it is very dangerous.

[36] The same law applies to each function. The inferior function is always associated with an archaic personality in ourselves; in the inferior function we are all primitives. In our differentiated functions we are civilized and we are supposed to have free will; but there is no such thing as free will when it comes to the inferior function. There we have an open wound, or at least an open door through which anything might enter.

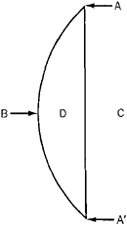

[37] Now I am coming to the endopsychic functions of consciousness. The functions of which I have just spoken rule or help our conscious orientation in our relations with the environment; but they do not apply to the relation of things that are as it were below the ego. The ego is only a bit of consciousness which floats upon the ocean of the dark things. The dark things are the inner things. On that inner side there is a layer of psychic events that forms a sort of fringe of consciousness round the ego. I will illustrate it by a diagram:

FIG. 2. The Ego

[38] If you suppose AA′ to be the threshold of consciousness, then you would have in D an area of consciousness referring to the ectopsychic world B, the world ruled by those functions of which we were just speaking. But on the other side, in C, is the shadow-world. There the ego is somewhat dark, we do not see into it, we are an enigma to ourselves. We only know the ego in D, we do not know it in C. Therefore we are always discovering something new about ourselves. Almost every year something new turns up which we did not know before. We always think we are now at the end of our discoveries. We never are. We go on discovering that we are this, that, and other things, and sometimes we have astounding experiences. That shows there is always a part of our personality which is still unconscious, which is still becoming: we are unfinished; we are growing and changing. Yet that future personality which we are to be in a year’s time is already here only it is still in the shadow. The ego is like a moving frame on a film. The future personality is not yet visible, but we are moving along, and presently we come to view the future being. These potentialities naturally belong to the dark side of the ego. We are well aware of what we have been, but we are not aware of what we are going to be.

[39] Therefore the first function on that endopsychic side is memory. The function of memory, or reproduction, links us up with things that have faded out of consciousness, things that became subliminal or were cast away or repressed. What we call memory is this faculty to reproduce unconscious contents, and it is the first function we can clearly distinguish in its relationship between our consciousness and the contents that are actually not in view.

[40] The second endopsychic function is a more difficult problem. We are now getting into deep waters because here we are coming into darkness. I will give you the name first: the subjective components of conscious functions. I hope I can make it clear. For instance, when you meet a man you have not seen before, naturally you think something about him. You do not always think things you would be ready to tell him immediately; perhaps you think things that are untrue, that do not really apply. Clearly, they are subjective reactions. The same reactions take place with things and with situations. Every application of a conscious function, whatever the object might be, is always accompanied by subjective reactions which are more or less inadmissible or unjust or inaccurate. You are painfully aware that these things happen in you, but nobody likes to admit that he is subject to such phenomena. He prefers to leave them in the shadow, because that helps him to assume that he is perfectly innocent and very nice and honest and straightforward and “only too willing” etc.,—you know all these phrases. As a matter of fact, one is not. One has any amount of subjective reactions, but it is not quite becoming to admit these things. These reactions I call the subjective components. They are a very important part of our relations to our own inner side. There things get definitely painful. That is why we dislike entering this shadow-world of the ego. We do not like to look at the shadowside of ourselves; therefore there are many people in our civilized society who have lost their shadow altogether, they have got rid of it. They are only two-dimensional; they have lost the third dimension, and with it they have usually lost the body. The body is a most doubtful friend because it produces things we do not like; there are too many things about the body which cannot be mentioned. The body is very often the personification of this shadow of the ego. Sometimes it forms the skeleton in the cupboard, and everybody naturally wants to get rid of such a thing. I think this makes sufficiently clear what I mean by subjective components. They are usually a sort of disposition to react in a certain way, and usually the disposition is not altogether favourable.

[41] There is one exception to this definition: a person who is not, as we suppose we all are, living on the positive side, putting the right foot forward and not the wrong one, etc. There are certain individuals whom we call in our Swiss dialect “pitch-birds” [Pechvögel]; they are always getting into messes, they put their foot in it and always cause trouble, because they live their own shadow, they live their own negation. They are the sort of people who come late to a concert or a lecture, and because they are very modest and do not want to disturb other people, they sneak in at the end and then stumble over a chair and make a hideous racket so that everybody has to look at them. Those are the “pitch-birds.”

[42] Now we come to the third endopsychic component—I cannot say function. In the case of memory you can speak of a function, but even your memory is only to a certain extent a voluntary or controlled function. Very often it is exceedingly tricky; it is like a bad horse that cannot be mastered. It often refuses in the most embarrassing way. All the more is this the case with the subjective components and reactions. And now things begin to get worse, for this is where the emotions and affects come in. They are clearly not functions any more, they are just events, because in an emotion, as the word denotes, you are moved away, you are cast out, your decent ego is put aside, and something else takes your place. We say, “He is beside himself,” or “The devil is riding him,” or “What has gotten into him today,” because he is like a man who is possessed. The primitive does not say he got angry beyond measure; he says a spirit got into him and changed him completely. Something like that happens with emotions; you are simply possessed, you are no longer yourself, and your control is decreased practically to zero. That is a condition in which the inner side of a man takes hold of him, he cannot prevent it. He can clench his fists, he can keep quiet, but it has him nevertheless.

[43] The fourth important endopsychic factor is what I call invasion. Here the shadow-side, the unconscious side, has full control so that it can break into the conscious condition. Then the conscious control is at its lowest. Those are the moments in a human life which you do not necessarily call pathological; they are pathological only in the old sense of the word when pathology meant the science of the passions. In that sense you can call them pathological, but it is really an extraordinary condition in which a man is seized upon by his unconscious and when anything may come out of him. One can lose one’s mind in a more or less normal way. For instance, we cannot assume that the cases our ancestors knew very well are abnormal, because they are perfectly normal phenomena among primitives. They speak of the devil or an incubus or a spirit going into a man, or of his soul leaving him, one of his separate souls—they often have as many as six. When his soul leaves him, he is in an altered condition because he is suddenly deprived of himself; he suffers a loss of self. That is a thing you can often observe in neurotic patients. On certain days, or from time to time, they suddenly lose their energy, they lose themselves, and they come under a strange influence. These phenomena are not in themselves pathological; they belong to the ordinary phenomenology of man, but if they become habitual we rightly speak of a neurosis. These are the things that lead to neurosis; but they are also exceptional conditions among normal people. To have overwhelming emotions is not in itself pathological, it is merely undesirable. We need not invent such a word as pathological for an undesirable thing, because there are other undesirable things in the world which are not pathological, for instance, tax-collectors.